Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

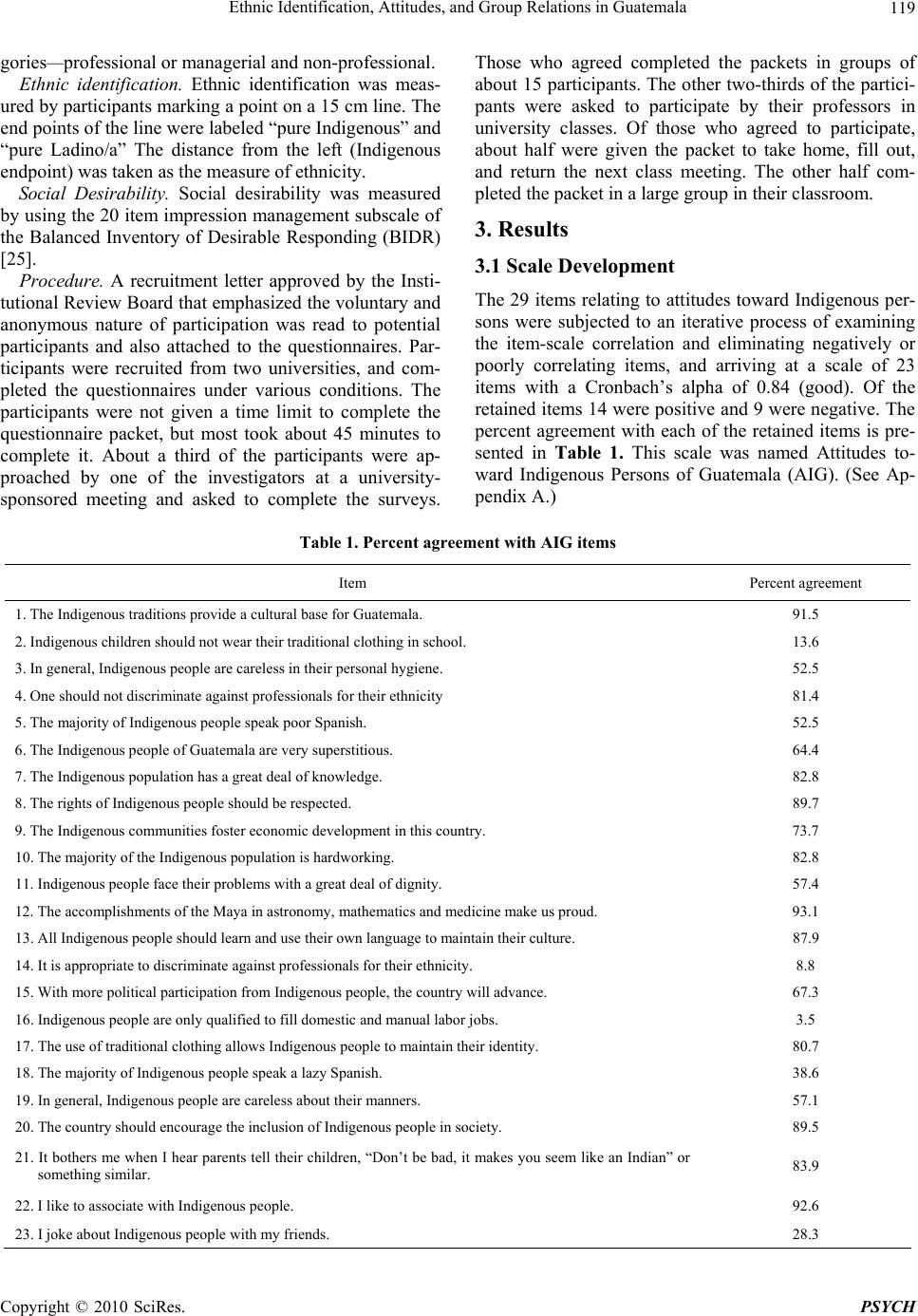

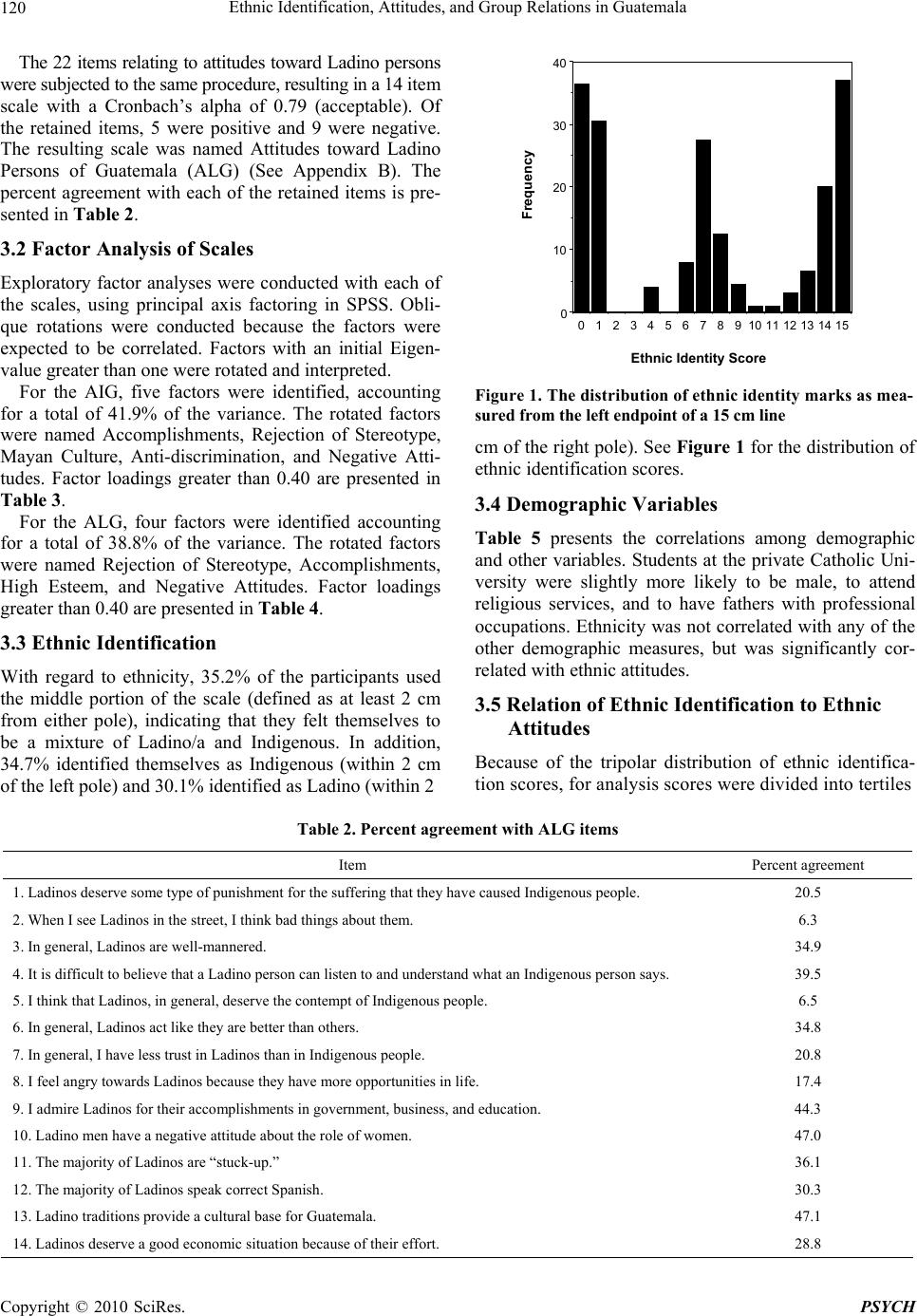

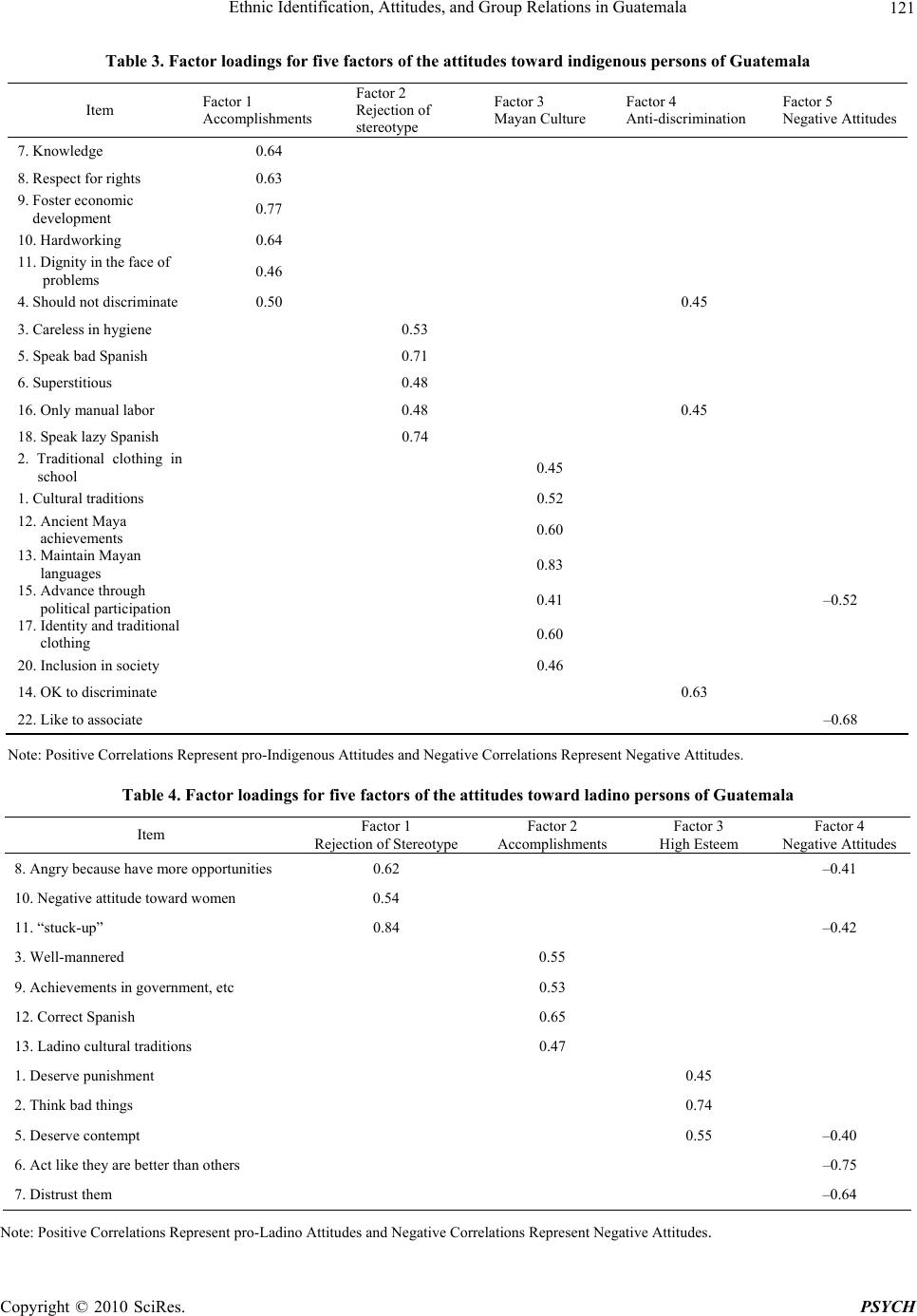

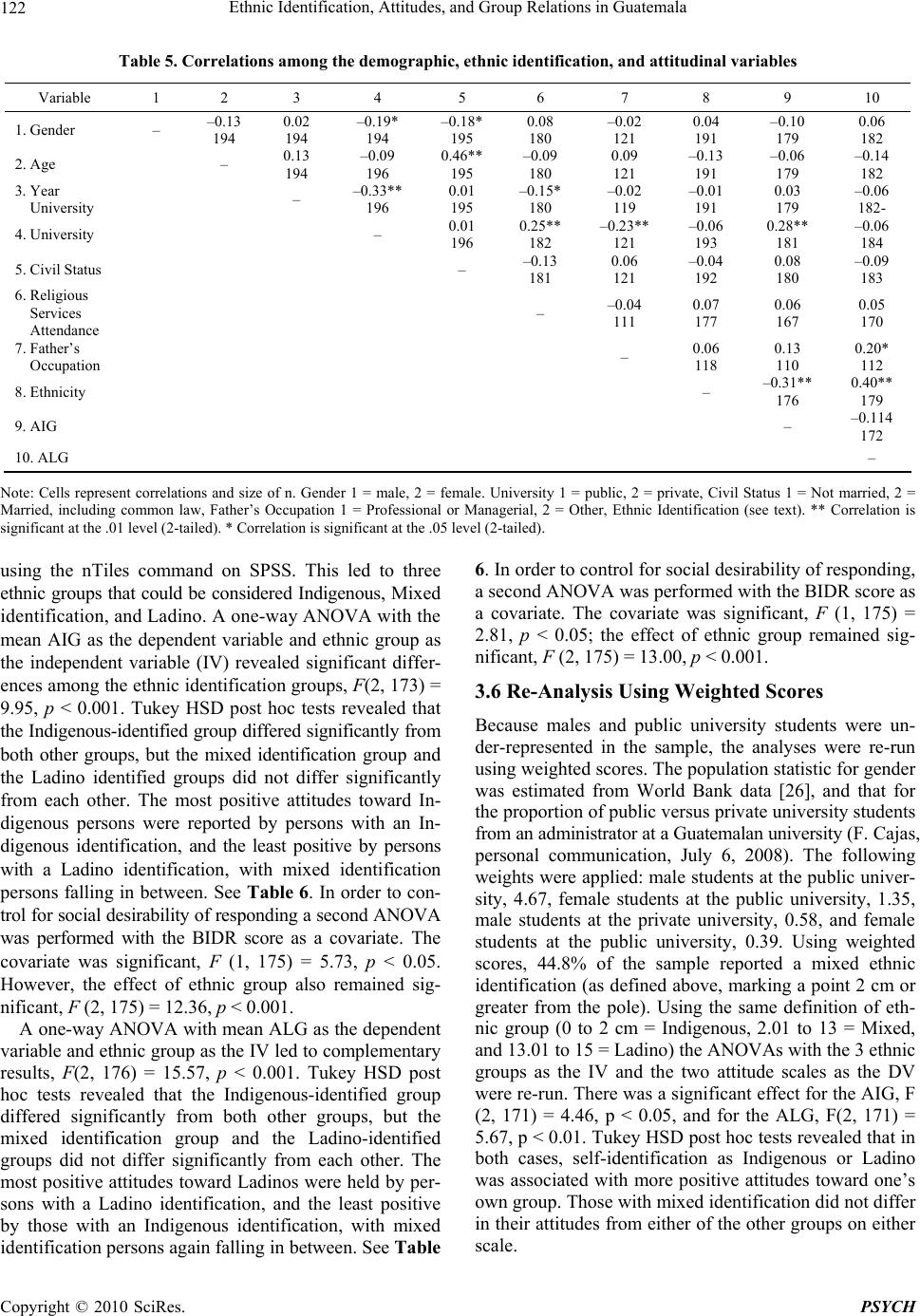

Psychology, 2010, 1, 116-127 doi:10.4236/psych.2010.12016 Published Online June 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH Ethnic Identification, Attitudes, and Group Relations in Guatemala* Judith L. Gibbons, Brien K. Ashdown# Department of Psychology, Saint Louis University, Saint Louis, USA. Email: gibbonsjl@slu.edu Received March 16th, 2010; revised April 5th, 2010; accepted April 10th, 2010. ABSTRACT Despite many studies that address relations between the two major ethnic groups—Indigenous and Ladino—in Guate- mala, there are no scales devised specifically to measure ethnic attitudes. Participants (196 university students) indi- cated agreemen t or disag reement on a four-poin t scale with a large pool of items exp ressing positive and negative atti- tudes towards the two group s, and, on a line from pure Indigenous to pure Lad ino, their own ethnic identification (the label they use to describe their ethnicity). Reliable scales measuring Attitudes toward Indigenous (AIG ) and Attitudes toward Ladinos (ALG) were constructed, and 35% of the pa rticipants claimed mixed ethnic identificatio n. Ethnic iden- tification was related to attitudes, with groups demonstrating in-group favoritism; that is, participants expressed more positive attitudes toward their own ethnic group. The results imply that the dichotomous categories of Ladino and In- digenous are inadequate for measuring ethnicity in Guatemala. The newly developed attitude scales may be used to advance knowledge about ethnic relations in Guatemala and to test the generality of findings relating to relations be- tween dominant and subord inate group s. Keywords: Gu at em al a, Ethnic Identification, Ladino, Indi g e no us, Maya, Ethnic Attitudes 1. Introduction “Guatemalans, we are a multiethnic, religiously and cul- turally plural country… So, why is there inequality be- tween Indigenous and Ladinos?… everything depends on how we educate our children…” [1]. Ethnic relations have a long an d conflict-r idden history in Guatemala. Numerous scholars, especially anthropolo- gists and historians, have examined ethnicity and its con- sequences in both the pueblos and urban areas of Guate- mala [2-7]. Originating with the Spanish conquest in 1523, lineage and blood were used to justify exploitation and oppression of Indigenous persons. For centuries the ethnic group defined as Spaniards or criollos (“home grown” or locally born persons of pure Spanish descent) was the source of the Guatemalan oligarchy [8]. T hroug h- out colonial times, independence, and into the present, relations between Indigenous persons and those of Euro- pean or mixed descent have been characterized by eth- nocentrism, paternalism, and discrimination against the Indigenous people [4,7,9]. Although the 1996 Peace Ac- cords that ended the 30-year armed conflict in Guatemala promised rights for Indigenous people, those accords have yet to be put into practice. An excellent summary of the history of ethnic relations in Guatemala is provided by the two volume series Ethnicity, state, and nation in Guatemala [10,11] and by its sequel Ethnic relations in Guatemala, 1944-2000 [12]. Those three volumes docu- ment ethnic divisions, attempts to “civilize” and “Ladi- nize” Indigenous persons, and continued ethnic dispari- ties within Guatemala. Today, ethnic relation s are part of the public d iscourse. Newspapers such as the Prensa Libre frequently feature articles and commentary on ethnic discrimination in Guatemala, and a prominent non-profit foundation El Centro de Investigaciones Regionales de Mesoamérica (CIRMA) sponsored an exhibit and a book series titled Por qué estamos como estamos (Why we are like we are) that highlighted ethnicity. The quote that introduces this article represents part of a letter to the editor of Prensa Libre. Ethnicity is also part of the political arena with a pan-Maya movement gaining increasing momentum [5, 13]. A presidential commission, Comisión Presidencial contra la Discriminación y el Racismo [Presidential Com- mission against Discrimination and Racism]—was char- ged in 2007 with investigating and developing plans to *An earlier version of this research was presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Cross-Cultural Research, San Antonio, Texas, 2007. #Now Brien K. Ashdown is in Department of Psychology, University o f Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, USA.  Ethnic Identification, Attitudes, and Group Relations in Guatemala 117 eliminate discrim ination and racism in Guatemala [14,15]. According to the latest census of Guatemala, the two major ethnic groups today are Ladino persons (58.3%) and Indigenous persons (40%). Within Guatemala La- dinos are defined as non-Indigenous persons or persons of mixed Indigenous and European descent. Most In- digenous in Guatemala are of Mayan heritage, speak one of the 22 different Mayan languages, and often identify themselves by the language they speak. Among those the most numerous are the K’iche’, who represent over one million persons, and the Kaqchikel and the Q’eqchi’, who are slightly less numerous with about 800,000 speakers each [16]. It is important to note that the ethnic categories are socially constructed. For various reasons, people can, and do, change their ethnic identification—the way they label or describe their ethnicity. In Guatemala, some in- dividuals may adopt the Spanish language and Western dress, and claim a non-Indigenous identity. The process of the transformation of individuals or communities from Indige n o us to Ladino ha s b een called Ladinizatio n [17]. A report by the Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo Humano [United Nations Human Devel- opment Programme] provided an extensive analysis of ethnicity and its correlates within Guatemala [16]. There is clear evidence for ethnic economic stratification. For example, approximately 80% of Indigenous persons live in poverty or extreme poverty, whereas approximately 45% of non-Indigenous live in poverty. There are almost no Indigenous persons represented in the highest socio- economic strata. Indigenous persons living in rural areas are most likely to be extremely poor; Thirty-eig ht percent of rural Indigenous persons earn less than one US dollar per day. Extreme poverty is also unequally distributed among the different language groups with almost 50% of rural Q’eqchi’ speakers earning less than one USD per day. The GINI ratio (a measure of economic disparity) of Guatemala is one of the highest in the world, at 0.57 in comparison to the United States at 0.41 and Japan at 0.25 [16]. Occupations are also distributed by ethnicity with the majority of Indigenous persons engaged in agriculture or the informal sector; non-Indigenous persons are more likely to be engaged in commercial or service enterprises [16]. Education is also unequally distributed. Thirty-eight pe- rcent of Indigenous persons have no education and 50% are educated only at the primary level; of non-Indigenous persons, those percentages are 17% and 50% respectively. Only 1% of Indigenous persons have post- secondary education. Literacy rates of young people (ages 15 to 24) reach 89.3% for Ladino persons but are lower for all Mayan language groups, for example the K’iche’ (73%), the Kaqchikel (82%), and the Q’eqchi’ (63%) [16]. In rural areas fewer than one third of Indigenous women can read or write [18]. Even though bilingual education in Spanish and the local Mayan language was guaranteed as part of the Peace Accords, of the 7,832 schools located in areas with a bilingual population, fewer than one fourth offer bilingual education [16]. There are similar ethnic disparities in health care. For example, with regard to childhood illnesses, over half of Indigenous persons treated their children themselves, and fewer than one fifth sought attention from doctors. The disparity with non-Indigenous persons is, in part, due to the higher numbers of Indigenous persons living in rural areas with less access to health facilities. But the conse- quence is that infant and childhood mortality rates are higher for Indigenous children than for Ladino children [16]. Although Guatemala is ranked overall as having me- dium human development as measured by he Human Development Index (based on health, education, and in- come indicators), the index is lower for Indigenous per- sons than for Ladino persons. For Ladinos the Index is 0.70, for Kaqchikel speakers 0.61, and for K’iche’ speak- ers 0.55 [1 6 ]. In 2005, the Vox Latina-Prensa Libre [16] did a study of social attitudes based on a representative sample of Guatemalans. The results documented widespread agree- ment that Indigenous persons in Guatemala face dis- crimination. For example, about three quarters of both Indigenous persons and Ladino persons responded that it is easier for light-skinned persons and Ladinos to find jobs than for dark-skinned persons, and Indigenous. Al- most 90% of both groups held that Ladinos are treated better in government and private offices. Slightly fewer believed that Ladinos were treated better on buses. Social attitudes between th e two ethnic groups tended to be mu- tually negative. The majority of those claiming Ladino ethnicity asserted that Indigenous persons were less agreeable, less intelligent, less clean, and less honest than Ladino persons, but also more hardworking. Conversely, persons claiming Indigenous ethnicity held that Ladinos were less hardworking, less agreeable, less intelligent, and less honest. However, the majority of both groups agreed that the other group had good manners. The groups disagreed on whether it was better to have a Span ish o r an Indigenous last name, with the groups showing in-group favoritism or preference for the last name of their own group. Reflecting widely-shared stereotypes (oversimpli- fied images of social groups), the majority of persons in both groups claimed that Indigenous persons were better at working in the fields and that Ladinos were better at working in offices [16]. Psychological studies related to ethnic relations in Guatemala are scarce. Using a task in which children as- signed adjectives to their own and other group, Quintana and his collaborators showed high levels of ethnic preju- dice among Ladino children living in a primarily K’iche’ Indigenous community. Older children, those with great- er ethnic and social perspective-taking skills, and those who had more terms to describe their own ethnicity Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH  Ethnic Identification, Attitudes, and Group Relations in Guatemala 118 showed less prejudiced responses [19]. Another study conducted within Guatemalan schools showed that chil- dren sought more help from teachers of their own ethnic- ity [20]. In addition Ladino teachers were similar to each other in their perceptions of Mayan students; Mayan teachers held more diverse views of Ladino students. Those results suggest that Ladino teachers may hold ste- reotypes about Mayan students. Falbo and De Baessa [21] addressed the issue of the value of Mayan (bilingual) education for Ladino and Indigenous middle school stu- dents. In a longitudinal study they found that both Ladino and Indigenous students showed greater academic gains if they attended Mayan schools. Using the Multiethnic Identity Measure, a scale developed in the USA (MEIM) [22] the authors measured ethnic identity and attitudes toward the other ethn ic group. Those students who se eth- nic identity increased during the school year also show ed changes toward more positive attitudes toward the other group [21]. The pursuit of research on ethnic relations in Guate- mala is hampered by the absence of scales that measure attitudes toward the ethnic groups. For example, on the MEIM, items refer not to specific groups, but to the gen- eralized other. A sample question is “I like meeting and getting to know people from ethnic groups other than my own” [22]. When applied in Guatemala the meaning might be unclear. For example, K’iche’ Mayans might interpret the item to apply to other Mayan groups, to La- dinos, or even to foreign visitors. The development of scales measuring attitudes towards specific other groups- those ethnic groups that are important in Guatemala- would greatly facilitate research on this issue. Thus, the major purpose of the present study was to develop scales specifically measuring attitudes toward Indigenous persons and attitud es towards Lad ino persons, and to examine attitudes of ethnic groups in Guatemala toward their own and the other group. In addition, a number of authors have decried the use of dichotomous (sometimes called bi-polar) categories to represent ethnicity in Guatemala. Those authors [17,23] pointed out that ethnic identification is more complex, fluid, nuanced, and multifaceted than the dichotomous categories suggest. An example of the fluidity of ethnic identification comes from research by Little [6] in his studies of May- ans working in markets. He reports examples of unusual construals of ethnicity. Some Mayan vendors, for exam- ple, told him that he (a European American) was Indige- nous. “Thank you, but why?” he asked. The response was two-fold—because he spoke the Mayan language Ka- qchikel well, and because he was disparaged and spit at by some Ladinos for his association with Mayas. So, at least under some conditions, part of the definition of be- ing Indigenous was being denigrated by Ladinos. Little [6] also reported how ethnic identification can be constructed to serve different purposes. The Mayan vendors often emphasized their Indigenous characteristics in order to sell their wares more effectively to tourists. In a survey among the Mayan vendors, the majority labeled them- selves as Indigenous but, in one wave of the study, also Guatemalan [6]. Later they said they had claimed the Guatemalan label because the city officials who regulate the vendors’ activities would look more favorably on them for espousing their national identity. These finding s show clearly that ethnic identification can be variously defined and also manipulated to fit the circumstances. Therefore, a second aim of the present study was to evaluate a new way to measure ethnic identification in Guatemala—on a continuum from pure Ladino to pure Indigenous. 2. Method 2.1 Development of the Items A pool of potential ite ms was written in Span ish based on consultation with informants who were diverse in age, ethnicity, and research experience, and from Guatemalan newspaper accounts of ethnic relations, government re- ports, and racist events. We compiled a list of 22 poten- tial items concerning attitud es toward Ladino p ersons and 29 potential items concerning attitudes toward Indige- nous persons. Approximately half of the potential items were positive (e.g. “Indigenous persons face their prob- lems with a great deal of dignity” or “In general Ladinos are well brought-up.”) The other half of the potential items were negative (e.g. “The majority of Indigenous people speak poor Spanish” or “In general Ladinos are stuck-up (conceited).”) The scale was a four-point scale with each point labeled: 1) strongly agree, 2) agree, 3) disagree, or 4) strongly disagree. Positively worded items were reverse-scored so that higher values represented more positive attitudes toward a group. 2.2 Evaluation of the Items Participants. The participants were 196 university stu- dents recruited from a private Catholic (n = 136) and a public (n = 60) university in Guatemala. To ensure geo- graphic diversity, the private university sample was ad- ministered at a meeting of students from campuses all over the country, and the public university sample came from a campus outside the capital in a region heavily populated by Indigenous persons. Ages ranged from 18 through 52 (M = 25.77, SD = 6.41). Seventy-six partici- pants were male (38.8%) and 120 female (61.2%), with gender unspecified on two questionnaires. Additional demographic information collected included frequency of attendance at religious services, marital status, years of attendance in the university, and father’s occupation. Fa- ther’s occupation was coded using the Dictionary of Oc- cupational Titles [24] and then collapsed into two cate- Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH  Ethnic Identification, Attitudes, and Group Relations in Guatemala Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 119 gories—professional or managerial and non-professional. Ethnic identification. Ethnic identification was meas- ured by participants marking a point on a 15 cm line. The end points of the line were labeled “pure Indigenous” and “pure Ladino/a” The distance from the left (Indigenous endpoint) was taken as th e measure of ethnicity. Social Desirability. Social desirability was measured by using the 20 item impression management subscale of the Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding (BIDR) [25]. Procedure. A recruitment letter approved by the Insti- tutional Review Board that emphasized the voluntary and anonymous nature of participation was read to potential participants and also attached to the questionnaires. Par- ticipants were recruited from two universities, and com- pleted the questionnaires under various conditions. The participants were not given a time limit to complete the questionnaire packet, but most took about 45 minutes to complete it. About a third of the participants were ap- proached by one of the investigators at a university- sponsored meeting and asked to complete the surveys. Those who agreed completed the packets in groups of about 15 participants. The other two-th irds of the partici- pants were asked to participate by their professors in university classes. Of those who agreed to participate, about half were given the packet to take home, fill out, and return the next class meeting. The other half com- pleted the packet in a large group in their classroom. 3. Results 3.1 Scale Development The 29 items relating to attitudes toward Indigenous per- sons were subjected to an iterative process of examining the item-scale correlation and eliminating negatively or poorly correlating items, and arriving at a scale of 23 items with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84 (good). Of the retained items 14 were positive and 9 were neg ative. The percent agreement with each of the retained items is pre- sented in Table 1. This scale was named Attitudes to- ward Indigenous Persons of Guatemala (AIG). (See Ap- pendix A.) Table 1. Percent agreement with AIG items Item Percent agreement 1. The Indigenous traditions provide a cultural base for Guatemala. 91.5 2. Indigenous children should not wear their traditional clothing in school. 13.6 3. In general, Indigenous people are careless in their personal hygiene. 52.5 4. One should not discriminate against professionals for their ethnicity 81.4 5. The majori t y of Indigenous people speak poor Spanish. 52.5 6. The Indigenous people of Guatemala are very sup e rstitious. 64.4 7. The Indigenous population has a great deal of know ledge. 82.8 8. The rights of Indigenous people should be respected. 89.7 9. The Indigenous communities foster economic development in this cou nt ry. 73.7 10. The majority of the Indigenous population is hardworking. 82.8 11. Indigenous people face their problems with a great deal of dignity . 57.4 12. The accomplishments of the Maya in astronomy, mathematics and medicine make us proud. 93.1 13. All Indigenous people shoul d learn and use their own language to maintain their culture. 87.9 14. It is appro p riate to discriminate against professionals for their ethnicity. 8.8 15. With more political participation from Indigenous people, the country will advance. 67.3 16. Indigenous people are only qualified to fill dome stic and manual labor jobs. 3.5 17. The use of traditional clothing allows Indígenous people to maintain their identity. 80.7 18. The majority of Indigenous people speak a lazy Sp anish. 38.6 19. In general, Indigenous people are careless abo ut their manners. 57.1 20. The country should encourage the inclusion of Indigenou s people in society. 89.5 21. It bothers me when I hear parents tell their children, “Don’t be bad, it makes you seem like an Indian” or something similar. 83.9 22. I like to associate with Indigenous people. 92.6 23. I joke about Indigenous people with my friends. 28.3  Ethnic Identification, Attitudes, and Group Relations in Guatemala 120 The 22 items relating to attitudes toward Ladino persons were subjected to the same procedure, resulting in a 14 item scale with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.79 (acceptable). Of the retained items, 5 were positive and 9 were negative. The resulting scale was named Attitudes toward Ladino Persons of Guatemala (ALG) (See Appendix B). The percent agreement with each of the retained items is pre- sented in Table 2. 3.2 Factor Analysis of Scales Exploratory factor analyses were conducted with each of the scales, using principal axis factoring in SPSS. Obli- que rotations were conducted because the factors were expected to be correlated. Factors with an initial Eigen- value greater than one were rotated and interpreted. For the AIG, five factors were identified, accounting for a total of 41.9% of the variance. The rotated factors were named Accomplishments, Rejection of Stereotype, Mayan Culture, Anti-discrimination, and Negative Atti- tudes. Factor loadings greater than 0.40 are presented in Table 3. For the ALG, four factors were identified accounting for a total of 38.8% of the variance. The rotated factors were named Rejection of Stereotype, Accomplishments, High Esteem, and Negative Attitudes. Factor loadings greater than 0.40 are presented in Table 4. 3.3 Ethnic Identification With regard to ethnicity, 35.2% of the participants used the middle portion of the scale (defined as at least 2 cm from either pole), indicating that they felt themselves to be a mixture of Ladino/a and Indigenous. In addition, 34.7% identified themselves as Indigenous (within 2 cm of the left pole) and 30.1% identified as Ladino (within 2 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9101112131415 0 10 20 30 40 Ethnic Identity Score Frequency Figure 1. The distribution of ethnic identity marks as mea- sured from the left endpoint of a 15 cm line cm of th e right po le). See Figure 1 for the distribu tion of ethnic identification scores. 3.4 Demographic Variables Table 5 presents the correlations among demographic and other variables. Students at the private Catholic Uni- versity were slightly more likely to be male, to attend religious services, and to have fathers with professional occupations. Ethnicity was no t correlated with any of the other demographic measures, but was significantly cor- related with ethnic attitudes. 3.5 Relation of Ethnic Identification to Ethnic Attitudes Because of the tripolar distribution of ethnic identifica- tion scores, for analysis scores were divided into tertiles Table 2. Percent agreement with ALG items Item Percent agreement 1. Ladinos deserve some type of pu nishment fo r the suffering that they have caused Indigenous people. 20.5 2. When I see Ladi nos in the street, I think bad things about t h em. 6.3 3. In general, Ladinos are well-mannered. 34.9 4. It is difficult to believe that a Ladino person can listen to and un derstand what an Indigenous per son says. 39.5 5. I think that Ladinos, in general, deserve the contempt of Indigenous people. 6.5 6. In general, Ladinos act like they are better than others. 34.8 7. In general, I have less trust in Ladinos than in Ind i genous people. 20.8 8. I feel angry towards Ladinos because they have more opportunities in life. 17.4 9. I admire Ladinos for their accomplishments in g o v er nment, business, and education. 44.3 10. Ladino men have a negative attitude about the role of women. 47.0 11. The majority of Ladinos are “stuck-up.” 36.1 12. The majority of Ladinos speak c orrect Spanish. 30.3 13. Ladino traditions provide a cultural base for Guatemala. 47.1 14. Ladinos deserve a good economic situation because of their effort. 28.8 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH  Ethnic Identification, Attitudes, and Group Relations in Guatemala 121 Table 3. Factor loadings for five factors of the attitudes toward indigenous persons of Guatemala Item Factor 1 Accomplishments Factor 2 Rejection of stereotype Factor 3 Mayan Culture Factor 4 Anti-discrimination Factor 5 Negative Attitudes 7. Knowledge 0.64 8. Respect for rights 0.63 9. Foster economic development 0.77 10. Hardworking 0.64 11. Dignity in the face of problems 0.46 4. Should not discriminate 0.50 0.45 3. Careless in hygiene 0.53 5. Speak bad Spanish 0.71 6. Superstitious 0.48 16. Only manual labor 0.48 0.45 18. Speak lazy Spanish 0.74 2. Traditional clothing in school 0.45 1. Cultural traditions 0.52 12. Ancient Maya achievements 0.60 13. Maintain Mayan languages 0.83 15. Advance throug h political participation 0.41 –0.52 17. Identity and traditional clothing 0.60 20. Inclusion in society 0.46 14. OK to discriminate 0.63 22. Like to assoc iate –0.68 Note: Positive Correlations Represent pro-Indigenous Attitudes and Negative Cor re l at i on s R epresent Ne g at i ve Attitudes. Table 4. Factor loadings for five factors of the attitudes toward ladino persons of Guatemala Item Factor 1 Rejection of Stereotype Factor 2 Accomplishments Factor 3 High Esteem Factor 4 Negative Attitudes 8. Angry because have more opportunities 0.62 –0.41 10. Negative attitude toward women 0.54 11. “stuck-up” 0.84 –0.42 3. Well-manner ed 0.55 9. Achievements in go ve rnment, etc 0.53 12. Correct Sp anish 0.65 13. Ladino cul tural traditions 0.47 1. Deserve punis hment 0.45 2. Think bad things 0.74 5. Deserve contempt 0.55 –0.40 6. Act like they are better than others –0.75 7. Distrust them –0.6 4 Note: Positive Correlations Represent pro-Ladino Attitudes and Negative Co rr e l at i on s R e pr esent Nega ti v e A tt i tudes. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH  Ethnic Identification, Attitudes, and Group Relations in Guatemala 122 Table 5. Correlations among the demographic, ethnic identifica tion, and attitudinal variables Variable 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1. Gender – –0.13 194 0.02 194 –0.19* 194 –0.18* 195 0.08 180 –0.02 121 0.04 191 –0.10 179 0.06 182 2. Age – 0.13 194 –0.09 196 0.46** 195 –0.09 180 0.09 121 –0.13 191 –0.06 179 –0.14 182 3. Year University – –0.33** 196 0.01 195 –0.15* 180 –0.02 119 –0.01 191 0.03 179 –0.06 182- 4. University – 0.01 196 0.25** 182 –0.23** 121 –0.06 193 0.28** 181 –0.06 184 5. Civil Status – –0.13 181 0.06 121 –0.04 192 0.08 180 –0.09 183 6. Religious Services Attendance – –0.04 111 0.07 177 0.06 167 0.05 170 7. Father’s Occupation – 0.06 118 0.13 110 0.20* 112 8. Ethnicity – –0.31** 176 0.40** 179 9. AIG – –0.114 172 10. ALG – Note: Cells represent correlations and size of n. Gender 1 = male, 2 = female. University 1 = public, 2 = private, Civil Status 1 = Not married, 2 = Married, including common law, Father’s Occupation 1 = Professional or Managerial, 2 = Other, Ethnic Identification (see text). ** Correlation is significant at the .01 level (2-taile d ) . * Correlation i s s ig ni fic an t a t th e . 05 level (2-tai led ). using the nTiles command on SPSS. This led to three ethnic groups that could be considered Indigenous, Mixed identification, and Ladino. A one-way ANOVA with the mean AIG as the dependent variable and ethnic group as the independent variable (IV) revealed significant differ- ences among the ethnic identification groups, F(2, 173) = 9.95, p < 0.001. Tukey HSD post hoc tests revealed that the Indigenous-identified group differed significantly from both other groups, but the mixed identification group and the Ladino identified groups did not differ significantly from each other. The most positive attitudes toward In- digenous persons were reported by persons with an In- digenous identification, and the least positive by persons with a Ladino identification, with mixed identification persons falling in between. See Table 6. In order to con- trol for social desirability of responding a second ANOVA was performed with the BIDR score as a covariate. The covariate was significant, F (1, 175) = 5.73, p < 0.05. However, the effect of ethnic group also remained sig- nificant, F (2, 175) = 12.36, p < 0.001. A one-way AN OVA with mean ALG as the dependent variable and ethnic group as the IV led to complementary results, F(2, 176) = 15.57, p < 0.001. Tukey HSD post hoc tests revealed that the Indigenous-identified group differed significantly from both other groups, but the mixed identification group and the Ladino-identified groups did not differ significantly from each other. The most positive attitudes toward Ladinos were held by per- sons with a Ladino identification, and the least positive by those with an Indigenous identification, with mixed identification persons again falling in between . See Table 6. In order to control for social desirability of responding, a second ANOVA was performed with the BIDR score as a covariate. The covariate was significant, F (1, 175) = 2.81, p < 0.05; the effect of ethnic group remained sig- nificant, F (2, 175) = 13.00, p < 0.001. 3.6 Re-Analysis Using Weighted Scores Because males and public university students were un- der-represented in the sample, the analyses were re-run using weighted scores. The population statistic for gender was estimated from World Bank data [26], and that for the proportion of public versus private university students from an administrator at a Guatemalan university (F. Caj a s , personal communication, July 6, 2008). The following weights were applied: male students at the pub lic univer- sity, 4.67, female students at the public university, 1.35, male students at the private university, 0.58, and female students at the public university, 0.39. Using weighted scores, 44.8% of the sample reported a mixed ethnic identification (as defined above, marking a point 2 cm or greater from the pole). Using the same definition of eth- nic group (0 to 2 cm = Indigenous, 2.01 to 13 = Mixed, and 13.01 to 15 = Ladino ) the A NOVAs w ith th e 3 ethnic groups as the IV and the two attitude scales as the DV were re-run. There was a significant effect for the AIG, F (2, 171) = 4.46, p < 0.05, and for the ALG, F(2, 171) = 5.67, p < 0.01. Tukey HSD post hoc tests revealed that in both cases, self-identification as Indigenous or Ladino was associated with more positive attitudes toward one’s own group. Those with mixed identification did not differ in their attitudes from either of the other groups on either scale. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH  Ethnic Identification, Attitudes, and Group Relations in Guatemala 123 Table 6. Means and standard deviations of AIG and ALG scores for the three ethnic identification groups Ethnic Group AIG ALG M SD M SD Indigenous (NTile 1) 3.30 0.33 2.51 0.37 Mixed (NTile 2) 3.14 0.31 2.74 0.28 Ladino (NTile 3) 3.03 0.37 2.84 0 .36 3.7 Correlations between Attitude Scales The correlation between the AIG and the ALG was r (172) = –0.11 , NS. When the data fro m persons falling in the first tertile of ethnic identification (a predominantly Indigenous identification) were examined separately, there was a correlation of r (59) = –0.25, NS, between the AIG and the ALG. When the data from persons falling in the third tertile of ethnic identification (a predominantly Ladino identification) were examined separately, there was a correlation of 0.14, r (59) = 0.14, NS, between the AIG and the ALG scores. 4. Discussion The most important outcome of the present study was the development of scales to measure attitudes toward the two major ethnic groups in Guatemala—Indigenous and Ladino. Those scales, named the AIG and the ALG, showed good reliability in terms of internal consistency as measured by Cronbach’s alpha. In addition, the sig- nificant relationship of ethnic identification to ethnic at- titudes suggests that the new scales are valid, and that they can dist i nguish am ong pe rsons of diffe r ent ethnicities. The second major finding of the present study is that in terms of ethnic identification many Guatemalan univer- sity students felt themselves to be neither Ladino nor Indigenous, but a mixture of the two. In the present study approximately one third of the participants claimed a mixed ethnicity. When the data were weighted to ap- proximate the population, almost 50% claimed a mixed ethnicity. Thus, a continuous scale might be a better measure of ethnic identification in Guatemala than the typical measure that uses boxes labeled as Indigenous or Ladino. The mixed-identification of many Guatemalans differs greatly from the clear separation of Indigenous and Ladino populations described by early anthropolo- gists [27-30] and reified by the categories used in current psychological research [19-21]. Although a number of authors [17,23] have urged researchers to move away from the dichotomous categorization of ethnicity in Gua- temala, to our knowledge, this is the first study to have taken that step and to have established the usefulness of a continuous measure. The use of a continuous line to re- cord ethnic identification does not imply that “Ladiniza- tion” is an inevitable, desirable, or even a prevalent, process for Indigenous persons of Guatemala. Ladiniza- tion is a unidirectional process of assimilation that was described by some anthropologists [31] and promoted by early Guatemalan government policies [11]. According to the Ladinization perspective, with greater socialization and more education Mayas would lose their Indigenous languages, dress, and customs, and become more like Ladino people. In contrast, the use of a continuum to de- scribe ethnicity in the present study allows individuals to represent their own ethnic identification in a more nu- anced and complex manner, but does not imply that indi- viduals will/or should demonstrate increasing Ladiniza- tion. Another point worth noting with regard to the results of this study is that negative ethnic attitudes in Guatemala are neither subtle nor covert. Over half of the respondents held that Indigenous people are careless in their manners and over one fourth admitted joking about Indigenous people with their friends. Over a third of respondents agreed that Ladino people are conceited and act like they are better than others. In an anthropological study of contemporary attitudes of Ladinos toward Indigenous, Hale [32] argued that many Ladinos have adopted an ideology of multiculturalism that continues to see the Indigenous as inferior, but with a rationale of “culture” rather than “race”. He notes attitudes that would be con- sidered “modern racism” in psychological terms, including a belief that in today’s world Mayas receive favored treatment. Although modern racism may be emerging in Guatemala, the present study revealed that old-fashioned prejudice is also in evidence. The results also demonstrate clear in-group favoritism. Attitudes towards one’s own ethnic group were most posi- tive, whether one identified as either Ladino or In d ig e n ou s . In-group favoritism in ethnic relations is a very wide- spread, if not universal, phenomena [33] and forms the basis of Social Identity Theory [34]. In this study, the mean attitudes towards th e “other” ethn ic group, althou gh significantly less positive, were neutral or slightly posi- tive. With this rating scale, a mean of 2.5 represents neu- tral attitudes. The mean score of self-identified Ladinos’ attitudes towards Indigenous persons was 2.9 (slightly positive) and that of Indigenous persons’ attitudes to- wards Ladinos, 2.5 (neutral). Thus, although there was clear evidence of in-group favoritism, there was no evi- dence of out-gr oup derogation. The relatio n of one’s own ethnicity to attitudes toward the other group cannot be accounted for by social desirability as the effect persisted even when corrected for socially desirable responding. Identifying oneself as a mix of both Indigenous and Ladino in Guatemala needs further exploration, because many questions remain unanswered. Are persons claim- ing mixed identity because of having a parent from each ethnic group? How do individuals integrate their mixed identities? Is the representation of a mixed identification constant or is it context dependent? There is increasing Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH  Ethnic Identification, Attitudes, and Group Relations in Guatemala 124 evidence that context influences the identity that indi- viduals claim [6,35], especially when people have several identities to choose from. In addition, there is evidence that persons with mixed identities are more positively disposed toward other groups [36]. In the present study people with mixed identification did not differ signifi- cantly in their attitudes from people with Ladino identi- fication. They were, however, less positive toward In- digenous persons, an d more positive toward Ladinos th an were Indigenous persons. A controversy in ethnic identity research is whether a strong ethnic identity fosters more positive feelings to- ward out-groups, or whether a strong identity with the in-group fosters negative attitudes toward the out-group. The two theories that propose these relationships are the multiculturalism hypothesis [37] and social identity the- ory [34] resp ectively. Although we did not ex plicitly test this hypothesis in the current study, there were no sig- nificant relationships b etween attitud es toward on e’s own and the other ethnic group. The present study has important implications for ethnic relations not only within Gu atemala but also in other set- tings. It is estimated that there are currently one million Guatemalan immigrants, refugees and sojourners living in the United States [38]. Those individuals are not uni- form in terms of their ethnicity and might be studied more veridically using a continuous measure of ethnic identification. In addition the AIG and ALG scales might be adapted for use in Latin American countries with similar histories of colonialism. Further studies might also address such issues as the relation of ethnic attitudes to experiences of racism and to social distance and whether a socia l dominan ce orie nta tio n [39] is related to negative out-grou p attitudes. The present study has a number of important limita- tions. Factor analysis revealed that the scales, although demonstrating adequate alpha, were composed of a num- ber of factors, with significant variance unaccounted for. This suggests that attitudes are complex and not easily represented by a single scale. In addition, the sample was not representative of all Guatemalans, especially because less than 4% of the Guatemalan population has the op- portunity to attend university [16]. Although the scales developed will be useful for investigating many issues related to ethnicity in Guatemala, they will not be appro- priate for the high percentage of the population that is illiterate; other, non-written tasks will need to be devised. With respect to ethnic id entification, even thoug h a bipo- lar scale may be preferable to “boxes”, it is likely that ethnic identification could be even better represented on a multidimensional measure that would allow individuals to rate the extent to which they id en tified with each of the major ethnic groups . 5. Conclusions Despite their limitations, the newly developed scales, the AIG and the ALG, will be useful for investigating issues regarding ethnicity in Guatemala, including the develop- ment of ethnic attitudes among youth, the effects of con- text on ethnic identity and ethnic attitud es, the relation of ethnic attitudes to particular experiences of contact or discrimination, and the instantiation of attitudes in daily life. They also might be used to address such questions as: “What is the role of physical attribu tes such as skin color in ethnic discrimination? “Are there situational or daily fluctuations in ethnic attitudes and ethnic identification? “Is a modern ethnocentrism emerging in Guatemala?” Future studies should also tease out the relative effects of socio-economic status and ethnicity. In addition, more attention needs to be paid to people in Guatemala who define themselves as having a mixed ethnic identification. Those individuals reflect the cultural diversity in Guate- mala and have the potential to breach ethnic divisions. Addressing ethnic attitudes and inter-group relations is critical to reducing prejudice and creating a more egali- tarian future in Guatemala. A 2006 report by the Guate- malan presidential commission CODISRA concluded “the fight against racial discrimination ought to be a central pillar in the construction of peace and democracy in Guatemala” [14]. Finally, the Guatemalan context, where approximately 50% of the population is made up of Indigenous people, could be used to examine theories of group relations in a setting where the subordinate group makes up a high percentage of the population. 6. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank Guillermina Herrera, Lisette Rodríquez, Carlos Rafael Yllescas Mijangos, María Mercedes Valdés, Claire T. Van den Broeck, Richard D. Harvey, Ana Gabriela González, María del Pilar Grazioso, and Walter E. Little for help during vari- ous stages of this study. REFERENCES [1] H. A. Abaj Xicay, “Guatemala Soy Yo,” Prensa Libre, May 2007, p. 17. [2] M. Camus, “Ser indígena en ciudad de Guatemala,” 2002. http://www.enlaceacademico.org/base-documental/bibliot eca/documento/ser-indigena-en-ciudad-de-guatemala/ [3] M. E. Casaús Arzú, “La metamorfosis del racismo en Guatemala,” Cholsamaj, 2002. [4] B. N. Colby and P. L. van den Berghe, “Ixil Country: A Plural Society in Highland Guatemala,” University of California Press, Berkeley, 1969. [5] D. Cojtí Cuxil, “The Politics of Maya Revindication,” In: E. F. Fischer and R. M. Brown, Eds., Maya Cultural Ac- tivism in Guatemala, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1996, pp. 19-50. [6] W. E. Little, “Mayas in the Marketplace: Tourism, Glob- alization, and Cultural Identity,” University of Texas Press, Austin, 2004. [7] S. Martínez Peláez, “La patria del criollo: Ensayo de in- Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH  Ethnic Identification, Attitudes, and Group Relations in Guatemala Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 125 terpretación de la realidad colonial Guatemalteca,” Uni- versitaria Centroamericana, 1998. [8] M. E. Casaús Arzú, “Guatemala: Linaje y racismo,” FLACSO, 1992. [9] K. B. Warren, “The Symbolism of Subordination: Indian Identity in A Guatemalan Town,” University of Texas Press, Austin, 1978. [10] A. Taracena Arriola, G. Gellert, E. Gordillo Castillo, T. Sagastume Paiz and K. Walter, “Etnicidad, estado y nación en Guatemala, 1808-1944,” CIRMA, 2002. [11] A. Taracena Arriola, G. Gellert, E. Gordillo Castillo, T. Sagastume Paiz and K. Walter, “Etnicidad, estado y nación en Guatemala, 1944-1985,” CIRMA, 2004. [12] R. Adams and S. Bastos, “Las relaciones étnicas en Gua- temala, 1944-2000,” CIRMA, 2003. [13] K. B. Warren, “Indigenous Movements and their Critics: Pan-Maya Activism in Guatemala,” Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1998. [14] Comisión Presidencial contra la Discriminacíón y el Racismo contra los Pueblos Indígenas en Guatemala (CODISRA), “El racismo, la discriminación racial, la xenofobia y todas las formas de discrimación,” Author, June 2006. [15] A. L. Blas, “He sufrido el racismo,” 2007. http://www. prensalibre.com/pl/2007/enero/21/161393.html [16] Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo Hu- mano (PNUD), “Diversidad étnico-cultural: La ciudadanía en un estado plural,” Informe Nacional de Desarrollo Humano, Edisur, 2005. [17] R. Adams, “An End to Ladinization,” Human Mosaic, Vol. 27, No. 1-2, 1993, pp. 44-49. [18] M. Heckt, “Guatemala Pluralidad, educación y relaciones de poder: Educación intercultural en una sociedad étni- camente dividida,” AVANSCO, 2004. [19] S. M. Quintana, V. C. Ybarra, P. G. Doupe and Y. De Baessa, “Cross-Cultural Evaluation of Ethnic Perspec- tive-Taking Ability: An Exploratory Investigation with U. S. Latino and Guatemalan Ladino Children,” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, Vol. 6, No. 4, 2000, pp. 334-351. [20] R. A. Chesterfield, K. I. Enge and F. E. Rubio, “Cross- Cultural Cognitive Categorization of Students by Guate- malan Teachers,” Cross-Cultural Research: The Journal of Comparative Social Science, Vol. 36, No. 2, 2002, pp. 103-122. [21] T. Falbo and Y. De Baessa, “The Influence of Mayan Education on Middle School Students in Guatemala,” Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, Vol. 12, No. 4, 2006, pp. 601-614. [22] J. S. Phinney, “The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure: A New Scale for Use with Adolescents and Young Adults from Diverse Groups,” Journal of Adolescent Research, Vol. 7, No. 2, 1992, pp. 156-176. [23] K. B. Warren, “Rethinking Bi-Polar Constructions of Ethnicity,” Journal of Latin American Anthropology, Vol. 6, No. 1, 2001, pp. 90-105. [24] United States Department of Labor, “Dictionary of Occu- pational Titles,” U. S. Government Printing Office, 1977. [25] D. L. Paulhus, “Two-Component Models of Socially De- sirable Responding,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 46, No. 3, 1984, pp. 598-609. [26] World Bank, “Guatemala. Female Tertiary Enrollment Share,” 1998. http://ddp-ext.worldbank.org/ext/DDPQQ/ report.do?method=showReport [27] R. Bunzel, “Chichicastenango: A Guatemalan Village,” J. J. Augustin, New York, 1952. [28] S. Tax, “Penny Capitalism: A Guatemalan Indian Econ- omy,” Smithsonian Institute of Social Anthropology, Washington, 1953. [29] C. Wagley, “Economics of a Guatemalan Village,” Mem- oirs of the American Anthropological Association, Kraus Reprint, 1969. [30] C. Wagley, “T he Social and Religious Life of a Guatema- lan Village,” Memoirs of the American Anthropological Association, Kraus Reprint, 1974. [31] D. R. Guaján Raxche, “Maya Culture and the Politics of Development,” In: E. F. Fischer and R. M. Brown, Eds., Maya Cultural Activism in Guatemala, University of Texas Press, Austin, 2002, pp. 74-88. [32] C. R. Hale, “Más que un Indio: Racial Ambivalence and Neoliberal Multiculturalism in Guatemala,” School of American Research Press, 2006. [33] R. Brown, “Social Identity Theory: Past Achievements, Current Problems and Future Challenges,” European Journal of Social Psychology, Vol. 30, No. 6, 2000, pp. 745-778. [34] H. Tajfel and J. Turner, “The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior,” In: S. Worchel and W. Austin, Eds., Psychology of Intergroup Relations, Nelson-Hall, 1986, pp. 6-24. [35] J. S. Phinney and L. L. Alipuria, “Multiple Social Catego- rization and Identity among Multiracial, Multiethnic, and Multicultural Individuals,” In: R. J. Crisp and M. Hew- stone, Eds., Multiple Social Categorization: Processes, Models, and Applications, Psychology Press, 2006, pp. 211-238. [36] J. S. Phinney and L. L. Alipuria, “At the Interface of Cul- tures: Multiethnic/Multiracial High School and College Students,” Journal of Social Psychology, Vol. 136, No. 2, 1996, pp. 139-158. [37] J. S. Phinney, D. L. Ferguson and J. D. Tate, “Intergroup Attitudes among Ethnic Minority Adolescents: A Causal Model,” Child Development, Vol. 68, No. 5, 1997, pp. 955-969. [38] J. Smith, “Guatemala: Economic Migrants Replace Politi- cal Refugees,” 2006. http://www.migrationinformation. org/Profiles/display.cfm?ID=392 [39] F. Pratto, J. H. Liu, S. Levin, J. Sidanius, M. Shih, H. Bachrach and P. Hegarty, “Social Dominance Orientation and the Legitimization of Inequality across Cultures,” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, Vol. 31, No. 3, 2000, pp. 369-409.  Ethnic Identification, Attitudes, and Group Relations in Guatemala 126 Appendix A The scale of “Attitudes toward Indigenous Persons of Guate- mala” in the original Spanish with English translations. En la sociedad Guatemalteca hay diferentes grupos étnicos. A veces las personas expresan las actitudes positivas o negativas acerca de los grupos. Por favor lee las siguientes frases con mucho cuidado y encierra en un círculo la respuesta que mejor represente tus sentimientos acerca de la frase. [In Guatemalan society there are different ethnic groups. Sometimes people express positive or negative attitudes about those groups. Please read the following phrases and circle the response that best represents your feelings about the phrase.] [1] (reverse-scored) Las tradiciones indígenas proveen una base cultural para Guatemala. [The Indigenous traditions provide a cultural base for Guatemala.] [2] Los niños indígenas no deben usar su traje típico en la escuela. [Indigenous children should not wear their traditional clothing in school.] [3] En general, los Indígenas son descuidados en su aseo personal. [In general, Indigenous people are careless in their personal hygiene.] [4] (reverse-scored) No se debe discriminar a los profesionales por su etnia. [One should not discriminate against professionals for their ethnicity.] [5] La mayoría de los Indígenas habla un mal español. [The majority of Indigenous people speak poor Spanish.] [6] Los Indígenas de Guatemala son muy supersticiosos. [The Indigenous people of Guatemala are very superstitious.] [7] (reverse-scored) La población indígena tiene muchos conocimientos. [The Indigenous population has a great deal of knowledge.] [8] (reverse-scored) Se deben respetar los derechos de los Indígenas. [The rights of Indigenous people should be respected.] [9] (reverse-scored) Los pueblos indígenas fomentan el desarrollo económico de este país. [The Indigenous communities foster economic development in this coun- try.] [10] (reverse-scored) La mayoría de la población indígena es trabajadora. [The majority of the Indigenous population is hardworking.] [11] (reverse-scored) Los Indígenas tienen mucha dignidad frente a sus problemas. [Indigenous people face their problems with a great deal of dignity.] [12] (reverse-scored) Los logros de los Mayas en astronomía, matemáticas, y medicina nos hacen orgullosos. [The ac- complishments of the Maya in astronomy, mathematics and medicine make us proud.] [13] (reverse-scored)Todas las personas Indígenas deben aprender y usar su propio idioma para mantener su cultura. [All Indigenous people should learn and use their own language to maintain their culture.] [14] Es propio discriminar a los profesionales por su etnia. [It is appropriate to discriminate against professionals for their ethnicity.] [15] (reverse-scored) Con más participación de los Indígenas en la política, el país avanzará. [With more political par- ticipation from Indigenous people, the country will ad- vance.] [16] Los Indígenas están preparados para ocupar solamente puestos domésticos y oficios manuales. [Indigenous peo- ple are only qualified to fill domestic and manual labor jobs.] [17] (reverse-scored) El uso del traje típico permite mantener la identidad entre los Indígenas. [The use of traditional clothing allows Indígenous people to maintain their identity.] [18] La mayoría de los Indígenas habla un español perezoso. [The majority of Indigenous people speak a lazy Spanish.] [19] En general, los Indígenas son descuidados en su educación. [In general, Indigenous people are careless about their manners.] [20] (reverse-scored) El país debe desarrollar la inclusión de los Indígenas en la sociedad. [The country should en- courage the inclusion of Indigenous people in society.] [21] (reverse-scored) Me molesta cuando oigo a los padres diciéndole a su hijo, “No seas necio, pareces indio” o algo como eso. [It bothers me when I hear parents tell their children, “Don’t be bad, it makes you seem like an In- dian” or something similar.] [22] (reverse-scored) Me gusta relacionarme con los indígenas. [I like to associate with Indigenous people.] [23] Hago chistes sobre los Indígenas con mis amigos. [I joke about Indigenous people with my friends.] Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH  Ethnic Identification, Attitudes, and Group Relations in Guatemala 127 Appendix B The scale of “Attitudes toward Ladino Persons of Guatemala” in the original Spanish with English translations. En la sociedad Guatemalteca hay diferentes grupos étnicos. A veces las personas expresan las actitudes positivas o negativas acerca de los grupos. Por favor lee las siguientes frases con mucho cuidado y encierra en un círculo la respuesta que mejor represente tus sentimientos acerca de la frase. [In Guatemalan society there are different ethnic groups. Sometimes people express positive or negative attitudes about those groups. Please read the following phrases and circle the response that best represents your feelings about the phrase.] [1] Los Ladinos merecen algún tipo de castigo por el sufrimiento que han causado a los Indígenas. [Ladinos deserve some type of punishment for the suffering that they have caused Indigenous people.] [2] Cuando veo a los Ladinos en la calle, pienso cosas malas sobre ellos. [When I see Ladinos in the street, I think bad things about them.] [3] (reversed) En general, los Ladinos son bien educados. [In general, Ladinos are well-mannered.] [4] Es difícil creer que una persona Ladina pueda escuchar y entender lo que una persona indígena dice. [It is difficult to believe that a Ladino person can listen to and understand what an Indigenous person says.] [5] Pienso que los Ladinos, en general, merecen el desprecio de los Indígenas. [I think that Ladinos, in general, deserve the contempt of Indigenous people.] [6] En general, los Ladinos son creídos. [In general, Ladinos act like the y are better than o t he rs.] [7] En general, tengo menos confianza en los Ladinos que en los Indígenas. [In general, I have less trust in Ladinos than in Indigenous people.] [8] Me siento enojado contra los Ladinos porque ellos tienen más oportunidades en la vida. [I feel angry towards Ladinos because they have more opportunities in life.] [9] (reversed) Admiro a los Ladinos por sus logros en el gobierno, los negocios, y la educación. [I admire Ladinos for their accomplishments in government, business, and education.] [10] Los Ladinos varones tienen una actitud negativa hacia el papel de la mujer. [Ladino men have a negative attitude about the role of women.] [11] La mayoría de los Ladinos es “fufurufo”. [The majority of Ladinos are “stuck-up.”] [12] (reversed) La mayoría de los Ladinos habla un español correcto. [The majority of Ladinos speak correct Spanish.] [13] (reversed) Las tradiciones Ladinas proveen una base cultural para Guatemala. [Ladino traditions provide a cul- tural base for Guatemala.] [14] (reversed) Los Ladinos merecen una buena situación económica por su esfuerzo. [Ladinos deserve a good eco- nomic situation because of their effort.] Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH |