Theoretical Economics Letters

Vol.07 No.05(2017), Article ID:78197,25 pages

10.4236/tel.2017.75092

Should the Evolution of Stakeholder Theory Be Discontinued Given Its Limitations?

Frederic Narbel, Katrin Muff

Business School Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

Copyright © 2017 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: July 11, 2017; Accepted: August 4, 2017; Published: August 7, 2017

ABSTRACT

Evolving views of stakeholder theory propose ways to transform societal problems into win-win solutions for the firm and society alike. Yet, and despite its success in expanding the understanding of the role of the firm in society, stakeholder theory has two main limitations. First, it is anchored in the traditional view of the firm defining it as an entity whose legitimate purpose is the generation of economic value for itself and its owners. Second, it relies on regulation as a compensatory mechanism for the externalities it generates. It is therefore fair to argue that at its current stage of development, stakeholder theory never leaves the confines of economic value maximization. As a result, stakeholder theory generates discussion on how to make its different interpretations comply with and serve the economic purpose instead of proposing a solution creating societal value. We therefore propose to interrupt the evolution of stakeholder theory and suggest a conceptual model derived from the study of best practices of successful firms using an outside-in approach to governance as an alternative. The intent is to redefine the purpose of the firm as one guided by societal goals instead of one driven by the pursuit of profit maximization.

Keywords:

Corporate Social Responsibility, Creating Shared Value, Corporate Finance, Stakeholder Theory, Short-Termism

1. Introduction

The beginning of the 21st century was marked by a severe and ongoing financial crisis [1] . It started in 2007 with the crash of the US housing market resulting in a full-blown crisis calling for palliative monetary and fiscal policies to prevent a collapse of the world’s financial system. A report published by the US Senate [2] concludes the crisis was brought about by failures of financial market regulation and supervision, failures of corporate governance, excessive risk-taking by banks and insurances and a systemic problem in accountability and ethics. The crisis illustrated that the actions of small groups of executives focusing on economic value maximization have the power to negatively affect the global economy [3] . In addition, the crisis challenged the “Invisible Hand” [4] argument suggesting that business, if left to pursue selfish goals, will inevitably end up doing good things for the public. These facts highlight the importance of rethinking the purpose of the firm to account for the interests of every stakeholder and not just those of a limited few―a view known as stakeholder theory [1] .

Stakeholder theory assumes that value creation is part of doing business. The definition of value varies depending on how the purpose of the firm is defined and how the responsibilities executives have towards their stakeholders are articulated [5] . The different answers given to those two points will define the nature of a firm’s relationship to its ecosystem and result in different views of stakeholder theory [6] .

Shareholder theory defines firms as entities whose sole purpose is to maximize their profits to reward their shareholders for the risk they took by investing in them [7] . This view of the firm is perceived as the origin of stakeholder theory because it establishes a notion of value creation [5] . The model is often criticized for not offering a complete vision of value creation because shareholders are defined as the sole beneficiaries of the value firms create [5] . Thus, Freeman [8] proposed an alternative asking firms to account for the interests of a broader spectrum of stakeholders. His view has in turn informed a broader perspective, Creating Shared Value (CSV), whose central premise sees the competitiveness of a firm and the health of the communities around it as being mutually dependent [9] .

Despite its success in expanding the understanding of the role of the firm in society, stakeholder theory has two main limitations. 1) Because it is derived from shareholder theory, it views society and its needs as something the firm can address successfully in economic terms [10] . 2) It assumes that firms act in compliance with the law [10] . Yet, a literature review of analysis by other academics of the limitations of regulation as a compensatory mechanism for negative externalities concludes that regulation does not offer a flawless solution [11] .

The evolutionary views of stakeholder theory presented earlier are mainly centered on strategies firms can adopt to mitigate the limitations of shareholder theory to become more sustainable―an approach known as an “inside-out” perspective [12] . This article proposes to discontinue the evolution and suggests redefining the purpose of the firm as one guided by an “outside-in” approach [12] as an alternative. The outside-in approach proposes a shift from minimizing a firm’s negative impacts on society to positioning it as a solution to address a societal issue. To support this objective, the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 explains the notion of the purpose of the firm and discusses the evolution of stakeholder theory from Friedman’s economic perspective to Porter & Kramer’s CSV model. In Section 3, we present findings derived from case studies conducted on companies using an outside-in approach to governance to inform our research. Section 4 is devoted to testing whether working with a company to anchor an outside-in perspective is possible. Section 5 proposes and discusses a new conceptual model derived from the learnings of Sections 3 and 4 to define the purpose of the firm and Section 6 presents our conclusions.

2. Theoretical Foundation and Literature Review

This section introduces theories that support our research and proposes conclusions derived from the review of relevant literature. It establishes the foundation from which the research proposition is derived.

We start by bringing clarity to the term “purpose of the firm”. The intent is to provide the context necessary to understand the subsequent discussion on the various interpretations of the perceived duties and responsibilities of the firm. We conclude by discussing the limitations of analysis by other academics of the limitations of regulation proposed as a compensatory mechanism for negative externalities to anchor our research.

2.1. The Purpose of the Firm

Management scholars have tried to explicit the purpose of the firm for almost a century. For example, Barnard [13] defined purpose as the core task of leadership [14] . More recently, Collins and Porras [15] suggested that the role of purpose is to inspire and guide the firm. To Ellsworth [16] , purpose is the end to which the strategy is directed and to Binney [17] , purpose is the answer to the question “Why does a firm exist”? This paper utilizes Mazutis and Ionescu- Somers’ [14] definition who see purpose as “the organization’s single underlying objective that unifies all stakeholders and embodies its ultimate role in the broader economic, societal and environmental context” [14] . We chose their definition because their proposal integrates previous views into one single definition while tying in the notion of stakeholders that is the focus of the discussion coming next.

2.2. The Evolution of Stakeholder Theory and Its Current Limitations

The literature on stakeholder theory has evolved from Friedman’s classic economic model [7] , to an approach asking firms to balance their stakeholders’ interests with their business objectives [18] . In turn, Freeman’s view has informed a broader perspective known as CSV [9] . In the next sections, we present those views and seek to clarify the gap in the literature we attempt to address.

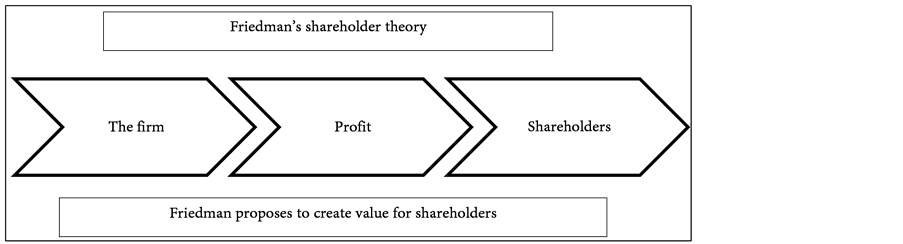

2.3. Friedman’s Shareholder Theory

Figure 1 is offered as a conceptual model of Friedman’s view. It establishes profit maximization as a firm’s sole objective and the shareholder as the only stakeholder to which it is socially responsible [7] .

According to Friedman [7] , a firm is to maximize its profits to reward its

Figure 1. Friedman’s shareholder theory.

shareholders financially for the risk they took by investing in it. He developed his theory in the 1970’s, a period when Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) was perceived as expenditure on philanthropy―a process used by firms to return a share of their profits to society [19] without necessarily offering a strategic connection to the rest of their business. In this context, he argues that those executives supporting CSR are disloyal agents to their shareholders because any reduction in earnings diverts the firm from its purpose if profit maximization is considered its sole objective [19] . The model has been widely accepted in the business realm because profit offers a convenient metric to measure success and assess the efficiency of a firm [20] . Moreover, its supporters argue that a firm cannot pursue societal objectives unless it is profitable. In their rationale, profitability generates the growth that is necessary for a firm to survive in a dynamic world [21] and to continue to provide the positive externalities that society has grown to expect from companies.

Friedman’s theory has led to an interpretation of the role of business executives known as the agency theory. It defines their function as agents serving their principal’s interests [22] . At the heart of the theory is the allegation that shareholders own the firm and therefore have authority over its activities [22] . This idea was developed further by Jensen & Meckling [23] who established an obligation for managers to conduct business in a way that maximizes shareholders’ economic returns [22] . Although agency theory has been widely accepted by firms, it is only recently that it became a dominant view in business philosophy [24] . The problem with Friedman’s model and resulting agency theory is that they fail to identify which social returns need to be pursued by firms given their focus on profit maximization. In addition, they do not set the rules defining an acceptable level of risk [25] . Over time, this has resulted in shareholders becoming fascinated with quarterly earnings thus forcing executives to concentrate solely on reported short-term financial performance measures [26] . This raises the question of what is a valid period during which profit is to be maximized. For example, investment banks―even if tightly regulated―may be tempted to invest in assets that are excessively risky in order to generate a higher return on their investments. This may in turn lead to a systemic risk if every bank operates based on the same model and starts to default at the same time [25] . In such case, the pursuit of short-term goals may result in macroeconomic imbalances followed by a rapid and uncontrolled economic downturn affecting the global economy resulting in a crash similar to the one experienced in 2007 [27] .

Despite these limitations, it is important to remember that shareholder theory does not support moral myopia [28] . It is a model whose presuppositions include voluntary cooperation and compliance with the law [5] . However, and by simplifying the function of a firm to a single goal―profit generation―it is likely to foster a worldview where executives do not understand their role as agents responsible to larger groups for their actions [5] . Hence, in 1984, Freeman found the model to be incomplete and in need of reworking to account for the interests of those stakeholders directly or indirectly affected by firms [18] . His work is presented in the following section and Figure 2 is proposed as a conceptual model.

2.4. Freeman’s Stakeholder Theory

Freeman [8] proposed a definition of stakeholder theory as an evolution of Friedman’s model [7] . It redefines firms as social institutions whose responsibilities go beyond their simple fiduciary responsibility to their shareholders and asks them to account for the interests of those stakeholders they affect [29] . The theory was proposed in the context of an extensive academic debate on whether the firm should separate its for-profit objectives from business ethics, a worldview known as the “Separation Thesis” [18] . For its proponents, Freeman’s view establishes a bridge reconciling the two objectives by creating consensus among competing concerns [30] [31] [32] .

Some academics such as Sundaram & Inkpen [28] have criticized Freeman’s proposal for adding complexity to management of firms by making them responsible to a larger group of stakeholders. Its opponents argue that including stakeholders to a firm’s value creation process can at best result in compromises because negotiation is necessary to deal with conflicting interests [33] . A second line of argumentation sees Freeman’s proposal as a precept undermining the principles on which a market economy is based, thus understanding it as a threat to political and economic freedom [34] . We think these criticisms arise from diametrically opposed ideologies more than from a real limitation of Freeman’s view. In fact, his model asks firms to articulate a shared sense of value distribution instead of entitling a single stakeholder group (shareholders) to all of it [5] . Thus, the question is to clarify the notion of fair value distribution more

Figure 2. Freeman’s stakeholder theory.

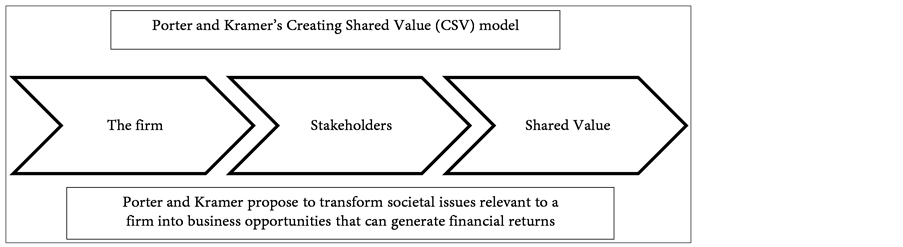

than questioning the fundamentals of Freeman’s proposal. This leads to Porter and Kramer [9] and their Creating Shared Value (CSV) model, discussed in the following section with Figure 3 offered as a conceptual model.

2.5. Creating Shared Value

Keeping in mind that various interpretations of stakeholder theory exist1, we propose to discuss Porter and Kramer’s CSV model [9] and present it as a next evolutionary step to Freeman’s model. Our choice is informed by the fact that their view has become one of the most widely accepted interpretations amongst academics and practitioners [10] . Their notion of shared value arose from their work [35] on the non-profit sector. It evolved into research [36] on corporations with a will to understand how firms could create societal value while at the same time improve their competitiveness and increase their economic returns. Their work grew into a larger analysis [37] resulting in their CSV model [9] . CSV proposes to transform societal issues relevant to a firm into business opportunities that can generate financial returns [10] .

CSV has been acclaimed for its capacity to translate societal issues into strategic targets that can be explained using financial metrics [10] . Others have tried to define societal issues as an ethical duty [38] , a response to business risk [39] [40] or a political responsibility [41] [42] with lesser success in the business realm. CSV’s second contribution is the clarification of the role of governments in regulating firms’ social initiatives, an area that has been left aside by much of the literature on stakeholder theory [43] [44] . In the CSV construct, governments are called upon to create regulation promoting shared value and establishing metrics allowing achievement of societal goals to be measured [9] .

CSV’s strengths may also be perceived as its weaknesses. For example, and referring to Porter’s Five Forces model2, we question why he defines certain stakeholders, such as suppliers, as competing with the firm for its profits [45] . Porter explains that under certain conditions, powerful suppliers could become a threat to a firm because they could command a bigger share of the value [45] . Furthermore, Crane, Palazzo, Spence and Matten [10] inquire why Porter’s view of strategy challenges the outcomes he sets CSV up to address. Interestingly, the

Figure 3. Porter and Kramer’s creating shared value model.

fundamental precept of stakeholder theory proposed by Freeman is for it to improve everyone’s circumstance [5] . Consequently, and keeping in mind Porter’s earlier work, it is unlikely that CSV can result in firms envisioning societal value distribution because CSV views the firm as an entity whose purpose is to maximize profit for itself and its owners [10] . In this context, CSV is probably a logical next step for firms to differentiate themselves from their competitors [10] , and thus, increase their market share and profit.

Crane, Palazzo, Spence and Matten [10] argue CSV has a second flaw resulting from its presumption of compliance with regulation and moral standards [9] . As demonstrated by Matten & Crane [41] for example, compliance with regulation remains a fundamental problem of multinational corporations because of the complexity of their value chains [10] . In this context, most companies will attempt to be compliant in their immediate transactional environment yet control tends to be lost as tiers of the value chain are expanded. In other words, fragmentation of the value chain is one deterring factor for transparency. Therefore, by ignoring those challenges and simply taking compliance with regulation for granted, CSV is likely to induce firms to continue to focus on low hanging fruits (project level type of actions) instead of solving systemic issues (a firm’s global value chain for example) that are necessary to truly create shared value [10] .

Both shareholder and subsequent views of stakeholder theory, recognize the importance of a firm’s financial success. They seek to support processes of value creation within the boundaries of the law yet differ when it comes to dealing with externalities. An externality is a common concept in economics to explain that certain costs (negative externalities) or benefits (positive externalities) are imposed upon groups that did not choose to partake in a firm’s value creation process. For example, electric cars may provide positive externalities in terms of energy efficiencies and greenhouse gas emissions, but negative externalities in other ways unless compensated (such as waste and resources). Shareholder theory, and its focus on wealth maximization, allows negative externalities to be generated as long as they are legally permissible. In contrast, stakeholder theory asks for those costs to be taken into consideration and calls on governments to act as the gatekeepers or on companies and industries to embark on voluntary initiatives. The need for regulation as compensatory mechanism and its effectiveness therefore is the subject of the following section.

2.6. Need for Regulation and Its Limitations

We undertook a literature review [11] of analysis by other academics of the limitations of regulation as a compensatory mechanism for negative externalities to understand its limitations and guide our research. In the business context, regulation seeks to address situations of market failure3 by ensuring that those who create the externalities bear their cost [46] . For example, regulation can be used as a compensatory mechanism for the pollution created by a manufacturing plant to correct the negative externality it imposes on local communities in the form of a tax or direct cost.

Our review identified three main limitations to regulation proposed as a compensatory mechanism for negative externalities. First, regulation is typically set in the national context yet companies tend to be international in their activities. Therefore, and without consistent regulation across borders, companies can relocate their activities or source their raw materials from jurisdictions with laxer standards thus limiting its effectiveness [47] . Second, “regulatory capture” results from a misalignment between the private interests of government actors and the public interest they are to serve [48] . It occurs when a regulatory agency, whose purpose it is to protect the public interest, instead favors the commercial or political interests of a small group that dominates the industry that the agency is charged with regulating [49] . Third, the complexity associated with the regulator’s task limits the effectiveness of regulation because the authorities rely on the industry’s technical knowledge to understand it [48] .

Next, we discuss voluntary initiatives adopted by firms to self-regulate because it is, largely, the path they choose to address the issues presented in this section.

2.7. Voluntary Initiatives to Self-Regulate

In light of the limitations of regulation presented in the previous section, an increasing number of firms resort to implement self-imposed control mechanisms to address the undesirable consequences of their business activities [50] . Self- regulation is the process whereby a firm protects its own adherence to a set of standards rather than relies on a governmental entity to monitor and enforce those [50] . An important form of self-regulation occurs when firms active in the same industry come together to establish a self-regulatory regime in the form of a professional industry association for example. Another approach is through the adoption of international standards such as the ones developed by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development.

In the context of negative externalities, it is important to remember that there will never be a perfect set of rules nor a flawless compliance monitoring system [51] . When it comes to questions about the ethics of firms’ policies and practices, self-regulating principles may help distinguish between what firms are legally bound and ethically obliged to do. Evidently, the appropriate level for any self- regulation will always result in a big debate on how much higher than the existing standards a firm should aim in terms of societal behavior without compromising returns. This argument is particularly relevant in the discussion of evolving views of stakeholder theory, as it is only valid when profit maximization is recognized as being part of a firm’s objective. In this context, voluntary initiatives may lead to constraints resulting in a non-level playing field?a phenomenon known as distortions in competition [52] . Distortions may appear when self-regulation creates barriers to entry distorting competition through accreditation bodies that unfairly discriminate against certain types of firms ( [52] , p. 21). Distortions may also arise from self-imposed constraints leading to a loss of competitiveness by restricting the number of opportunities a firm may pursue because of ethical reasons for example.

Despite the challenges self-regulation represents, we hypothesized that it may help firms ensure compliance with their purpose. We therefore conducted two case studies with the intent to learn from best practices and identify limitations to contribute to the literature on the purpose of the firm. We present our research and findings in Section 3.

3. Studying Best Practices of Companies Using an Outside-In Approach to Governance

We conducted our research in two phases. Phase 1 consists of case studies of firms employing an “outside-in” approach to define their purpose. Phase 2 relies on Action Research (AR) as a methodology to test whether working with a com- pany to anchor an outside-in perspective is possible or not. The research methodology, findings and limitations are presented in Section 44.

3.1. Methodology―Phase 1

The need to find a methodology allowing differentiating companies employing a multi-stakeholder approach to governance from their traditional counterparts arose at the onset of our research. We opted for the Business Sustainability Typology (BST) proposed by Dyllick & Muff [12] because it offers a scale against which to assess a firm’s business model. The scale ranges from “Business-as- usual” to “Truly Sustainable Business” [12] . A business-as-usual firm is defined as one taking the traditional, purely economic view to guide its operations [12] . In contrast, truly sustainable firms go beyond the Triple Bottom Line5 framework and seek to affect positively the environment and society [12] . The BST is relevant to our research because it provides a peer-reviewed model allowing for the identification of firms employing an outside-in approach to define their purpose. Yet, and because the framework is relatively young, it is not a widely tested concept which might be a limitation.

We focused on understanding whether the firms we were considering for our case studies had different methodologies or processes in place to account for their stakeholders. To do so, we defined six selection criteria to sort through a sample of 401 possible partners as follows: 1) the firm had to be located in Europe for research convenience reasons; 2) it had to be affiliated to a program, a network or an organization supporting sustainability; 3) it had to be a recognized sustainability leader confirmed by a sustainability award for example; 4) it had to qualify as a Truly Sustainable Business type of organization [12] ; 5) it had to be active in the financial industry and; 6) it either had to be a cooperative or a joint stock company.

We faced difficulties to convince firms to collaborate on case studies because some asked for a confidentiality agreement to be signed prior to disclosing any information. These firms therefore had to be abandoned as such an agreement would have limited the possible outcome of our research. Other firms appeared to be sustainable on the surface judging, for example, by the sustainability awards they had received but proved to be mere examples of “green washing” when assessed against the BST. In conclusion, 32 companies were approached, 4 case studies were initiated, 1 case study on Alternative Bank Schweiz (ABS)6 was published [53] and 1 case study on Merkur Cooperative Bank7 was approved for publication [54] .

The research methodology we employed is based on a mixed method research design relying on quantitative and qualitative methods [55] . The quantitative research consisted of the administration of a SCALA (Sustainable Culture and Leadership Assessment) survey which is a tool developed by Miller Consultants. It assesses sustainability-specific and organizational culture content demonstrated in other research to influence the adoption and execution of a sustainability strategy [56] . It allows researchers to uncover particular strengths and to detect areas that need to be addressed to better support sustainability goals. Surveys were conducted with both ABS and Merkur at the onset of our collaboration with both companies. This allowed us the opportunity to take a “snap-shot” of the sustainability culture at each organization. There were 24 respondents to the SCALA survey at ABS out of 29 requests sent. There were 15 respondents at Merkur out of 23 requests sent. With a response rate of 83% and 65% respectively, the response rates were higher than the average 40% Miller Consultants usually receives when administering the survey8. The reasoning guiding the decision to use the SCALA survey was that the results would highlight specific patterns regarding decision-making within the firm and provide material to prepare for the qualitative research phase (interviews).

The qualitative research consisted of desk research of publicly available archives related to the history of the companies and the carrying out of interviews. To our advantage, both ABS and Merkur had documented their history in detail, by explaining the logic leading to key decisions about their purpose over time. Using this information and the SCALA results, we were able to design interview protocols focusing on specific points in time when decisions about the purpose of the company were made and when it was challenged thus contributing to the overall quality of discussion. This was particularly useful when we discussed self-regulation and the challenges it represents. The interviews were conducted either in person on site at the partner organizations’ offices or over conference calls. The case studies and related findings are discussed below.

3.2. Case Study 1―Alternative Bank Schweiz

A survey conducted in 1982 in Switzerland revealed a demand for an alternative to existing banks. Citizens were asking for a solution that would support societal goals and ensure that banks would move away from focusing solely on profit maximization objectives [53] . ABS’ founders, following an outside-in approach, proposed a new type of bank as a solution to address the need. Below, we highlight the best practices that ABS applies to support its objectives before discussing them in the context of stakeholder theory.

3.2.1. Purpose Definition

ABS worked for approximately 8 years on defining its values and purpose. This may seem a long time yet it is the direct result of the democratic nature of the organization and its focus on building consensus amongst stakeholders9. The process resulted in the definition of ABS’ mission as one prioritizing pursuit of ethical principles over profit maximization.

It is our view that the approach ABS employed to identify its purpose differed from approaches that could result from the views on stakeholder theory discussed in Section 2. ABS looked at the bigger picture, identified social, environmental, and governance deficiencies in that context and proposed itself as the best solution to address societal needs. This is a very different approach to “business-as-usual”, where companies tend to look at improving existing practices in order to create societal value; in other words, a thoroughly “outside-in” approach. In addition, the decision ABS took not to solely pursue profit maximization objectives is in disconnect with Friedman’s view and subsequent evolution of stakeholder theory. Discounting for-profit objectives can be a strategic decision that comes at a cost to a company and for this reason, needs to be explained. We address this in the following section.

3.2.2. Transparency

Because ABS does not pursue for-profit objectives, it has to ask for its customers and shareholders’ contribution in the form of higher interests and lower returns because supporting societal goals comes at a cost. In exchange, the bank commits to total transparency and regularly informs its stakeholders about the shared value its activities generate. To that effect, ABS created a quarterly publication called Moneta providing information on its loans, on the purpose of the projects it finances and the persons behind them. Further reinforcing its commitment to transparency, the bank introduced a review mechanism in 2013 allowing it to quantify its contribution in terms of societal value [53] . It publishes the results in its annual report.

Despite a clear articulation of its objectives, ABS’ founders developed fear that the concentration of power to a minority of shareholders could divert the bank from its purpose [53] . ABS therefore developed stringent articles of association defining the values guiding the organization and establishing protection mechanisms to address that risk. Our next section explains the mechanisms that the bank developed.

3.2.3. Limiting Shareholder Power

ABS developed two protection mechanisms to prevent diversion from its original purpose. First, the bank set a cap on share ownership and second, it established a process to filter out investors that were unlikely to support the bank’s goals and values. Initially, ABS limited individual share ownership to a maximum of 3% of all shares registered. The cap had to be increased to 5% in 2014 because the bank’s growth affected its equity ratio10 [53] . As a result, the bank needed to find a solution to increase its financial reserves so that it could remain in compliance with Swiss banking law. Also, and because the number of large-scale value based investors who could qualify as possible shareholders was limited, the bank had to allow them to own a larger number of shares. ABS’ CEO commented that the process was challenging because the bank had to build consensus with its stakeholders around its decisions. At the time, it was feared that allowing shareholders to grow in importance would jeopardize future General Assemblies because larger shareholder interests would prevail. ABS proposed two solutions to remedy the problem. It offered to a) disclose the names of large shareholders present in the audience during a General Assembly and b) to be more specific about the decisions that needed qualified or unqualified majorities.

The second protection mechanism ABS developed consisted in selecting the type of shareholders it allows to invest in the bank. It defined them as individuals, corporations or public entities supporting its goals and ideals and who support activities that do not seek profit maximization. Interestingly, ABS went further by establishing a mechanism allowing it to buy shares back if certain conditions relative to their acquisition were no longer met [53] . Practically, this meant that the bank had a tool to safeguard its interests should a large shareholder’s vision or aspiration have changed over time and present a risk to ABS’ purpose. Limiting shareholder influence also presented a major threat. Suppose that ABS could have benefited from a change in direction or management. Large shareholders may not have been able to undertake appropriate action to effect such a change because the bank or its management may be inclined to buy back those shareholders’ shares by arguing they are no longer in compliance with the firm’s values [57] .

The bank’s action to limit the influence of shareholders led us to hypothesize that shareholders can be a potential threat to firms that have abandoned for- profit objectives. This, because they have the power to force companies to deviate from the pursuit of societal goals in order to have them focus on for-profit objectives. We assumed the risk was the consequence of the business realm in which firms operate because it is an environment in which shareholder primacy and resulting objectives of profit maximization still prevail. On the one hand, our case study provides a practical example illustrating the need to regulate shareholder power. On the other hand, the literature shows that if regulated too tightly, shareholder power may not suffice to make the changes necessary to support the firm’s long-term success. ABS established a Board of Ethics as a mechanism to address the limitation and it is described in the following section.

3.2.4. Board of Ethics

In its original format, the ABS Board of Ethics was appointed by the Board of Directors for 3 years and was defined as an independent control entity whose role was to guarantee the bank’s compliance with its values. The board consisted of seven members who personified the ethical motivations that led to the creation of the bank. The board was not meant to intervene directly in the bank’s operations yet had to act as the supreme body of control [53] .

In 2005, the Board of Ethics concluded that its format was no longer an adequate solution to protect ABS’ values because it often conflicted with the Board of Directors. In the original design, the Board of Directors was tasked with running the bank’s day-to-day operations while the Board of Ethics was given oversight of the entire business with no decision-making power. Therefore, and in order to address the problem, the proposal was to establish the Board of Directors as an entity free to act within a clearly defined framework of ethical strategic objectives. The Board of Ethics, on the other hand, recommended its own dissolution. It proposed that its responsibilities be transferred to the Institute of Business Ethics at the University of St-Gallen11. In this role, the institute has oversight over the bank’s ethical orientation and publishes an independent report in ABS’ annual report [53] . This unusual arrangement eliminates the problematic associated with determining the position of the Board of Ethics within the organization and provides a clear separation of decision-making powers.

Deepening our inquiry, we undertook development of a second case study written in collaboration with Merkur Cooperative Bank. The objective was to identify shared-practices and differences between the two firms. We were particularly interested to find out whether Merkur also identified its business context as a threat requiring the adoption of self-regulatory mechanisms. In the following sections, we present the conclusions of our research.

3.3. Case Study 2―Merkur Cooperative Bank

3.3.1. Purpose Definition

Merkur identified a demand in Denmark for a bank that would support small organic enterprises that would typically not qualify for loans from mainstream banks. They proposed Merkur as a solution and enabling mechanism for such enterprises. It developed from a private savings and loan association into a cooperative bank over the years. The driving force behind Merkur’s purpose definition was its CEO who views a bank as “a link between people with ideas and people with money” [54] . As a result, Merkur defined itself as an organization, which is to finance the society of the future by giving stakeholders the opportunity to use their money or economic activity to promote a society that will remain sustainable far into the future, for people and the environment alike [67] .

Similar to ABS, Merkur’s approach to defining its purpose differs from the existing literature on stakeholder theory because it decided to distance itself from for-profit objectives and pursue the creation of societal value instead. Interestingly, Merkur also identified the importance of communicating with its stakeholders to that effect. The method it followed is different to that of ABS and is presented in the following section.

3.3.2. Communicating with Stakeholders

The bank translated its purpose into a set of core values providing its employees with a framework to guide their activities. As with ABS, those activities needed to be transparent because the bank was asking its customers and cooperative members to pay higher interest rates and accept lower dividends to support its activities. Merkur created a website allowing its users to access every project financed by the bank. It provides a brief introduction on the project, the purpose it serves, its location and contact information in case more information is needed. This interactive tool not only serves the purpose of informing stakeholders but also acts as a control mechanism as it allows them to judge the quality of the project against the bank’s values and voice their concerns if necessary to trigger a change.

3.3.3. Protection Mechanisms

As with ABS, Merkur also feared the possible influence of its cooperative members. It saw them as a force that could potentially affect its original purpose and transform the bank into an entity tasked solely with generating financial returns. Therefore, Merkur decided to limit their power. The bank did not opt for a cap on ownership like ABS. Instead, it decided to limit the vote of its members to one per person and this regardless of the percentage of capital owned. This benefits the bank as it allows it to raise capital with existing members without having them attain more voting rights. In addition, Merkur’s articles of association grant the Board of Directors authority to take account of the size of a member’s capital and take corrective actions if necessary.

3.4. Summary

In Section 3, we reviewed two examples of firms taking an outside-in approach to defining their purpose. Having clearly established the societal problem they seek to solve, these firms identified their business realm, (shareholders solely pursuing value maximization objectives), as a threat to their original outside in-based purpose. As a result, both firms adopted protective mechanisms to counter the threat and ensure compliance with their core values. The case studies also illustrate that the protection mechanisms in place may need to be adjusted overtime as they may not necessarily be the most effective tool in their original design.

The fact that both ABS and Merkur have been in operation for more than 30 years illustrates that firms that do not pursue for-profit business objectives can survive and thrive in today’s business environment. This conclusion allows us to depart from worldviews seeing profit maximization objectives as a prerequisite to business success. We therefore sought to work with executives to test whether it is possible to shift their worldviews from a business-as-usual to an outside-in perspective. The methodology employed to that effect and resulting findings are presented in the following section.

4. Is an External Purpose-Orientation a More Effective Way to Self-Regulate?

The second part of our research focused on an AR intervention. We collaborated with a group of South African executives (CEO, CFO and CTO) working for a company producing nutritional supplements and who were contemplating the possibility of launching their next business venture. The name of this company cannot be disclosed for confidentiality reasons. The company retails its products online and through dealers globally. It was incorporated in 2007 and was sold to a larger venture in 2013. It is listed on the Johannesburg stock exchange and had a turnover of approximately USD 200 million in 2015.

4.1. Context

South Africa is a nation plagued by bribery, unemployment12 and social inequalities. It is trying to reinvent itself into a society of multiple ethnicities, which is a very complex task because past governments implemented a system of institutionalized racial segregation and discrimination between 1948 and 1991 [58] . As a result, the South African society has grown to expect that firms address some of the government’s failures by acting ethically, not behaving criminally and share some of their wealth with the country’s poorest through programs of strategic philanthropy [59] . This discussion is important in order to understand the context in which the research was conducted and to interpret the journey the executives went through. It also provides an interesting contrast to the discussion presented earlier on the evolution of views of stakeholder theory that proposes mainly the perspective of a developed world.

4.2. Methodology―Phase 2

We saw an opportunity to adopt AR methodology for the second phase of our research because it can be used to guide a reflective process involving both research scholars and practitioners with the purpose of generating knowledge derived from a practical case. This approach requires the researchers to participate actively in a change management situation within an existing organization while at the same time conducting research. To that effect, we designed a four-step AR intervention consisting of: 1) intervention planning; 2) workshops; 3) individual interviews and 4) a result validation meeting. The four-step process is derived from Reason & Heron’s [60] work on co-operative inquiry. It supports our research objective to test whether it is possible to have companies abandon for-profit objectives and embrace an outside-in purpose instead. This, because the methodology offers a process to conduct research with those people whose actions are under study with the purpose of inducing a change [61] . In addition, we have used learning history as a complementary method to co-operative inquiry to disseminate what we, as a group, had learned while working together [62] .

Of note, AR is a research methodology that does not result in results that are possible to test empirically. This constitutes its main limitation. In AR, the “language of proof is disappearing” [63] . The research process starts with the identification of a practical problem, then a research question is formulated and by systematically engaging with it, data is generated in order to create evidence. This evidence then allows a claim of knowledge to be made. The AR philosophy does not aim to prove a result. Its primary purpose is to help the action researcher to improve a practice. The expected outcome therefore is for the researcher to be able to claim that a defined area of work has been improved and to be able to generate knowledge from the findings resulting from the research. In the AR methodology, validity of data comes through a thorough description of the research method and of what the researcher did, a clear explanation outlining why the researcher engaged in the process in the first place, a precise definition of the outcomes the researcher expected to achieve and then a clear benchmarking of whether those outcomes were achieved and if not why. For a claim to validity to be made, the researcher has to explain how the data has been gathered and how the evidence has been generated. Finally, the researcher presents the research findings to a validation group to attain confirmation on the conclusions of the research. Only then can the researcher proceed and share the findings and conclusions in the public domain for further testing [63] .

4.3. Key Learnings

At the onset of our research, we asked the executives to reflect on the purpose of their organization and the values guiding it. We were particularly interested in defining what an ideal company should be like for their next business venture. Surprisingly, the executives stated they had never discussed their value system amongst themselves [64] . When asked to reflect on the reasons leading them to sell their company, they commented that their industry was becoming very competitive with the market shifting from value to price. In technical terms, the market was becoming competition-driven?a realm in which prices are determined by the pricing level at which a targeted level of market-share is attained by the firm [65] . The resulting erosion of margin led the executives to envision various scenarios to re-position their company. At that time, they were approached by a group of investors whom, in the words of the executives, “sold them a nice story” [64] . The investors were willing to buy their company in order to consolidate it with some of its most reputable competitors. This solution was intended to alleviate some of the price pressure the executives and their competitors were experiencing. The investors also promised the executives that they would be part of the newly created management structure. At that point, in time, the executives thought they had found the solution they were looking for [64] . Rapidly, however, the new owners imposed short-term value creation objectives. For example, they asked the executives to keep their inventory levels to a minimum in order to improve their financial statements. This often resulted in the company being unable to fulfil orders. In addition, the executives were asked to terminate their marketing team as the new owners thought the department was too expensive. From a short-term perspective, the decision made sense. Yet, when looked at from a long-term perspective, the decisions contradicted the company’s strategy since the marketing department was vital to creating a strong brand [64] . These symptoms led the executives to question the purpose of their firm.

The AR intervention led the executives to realize that their initial concern was to run an efficient and profitable business and made them appreciate the importance of gaining a common understanding of the value that would guide their next venture [64] . They commented that their value system prior to the sale was about offering superior quality products and services to their customers. They acknowledged they should have taken the time to reflect and find a definition of their long-term objectives guiding their future activities prior to agreeing to the sale [64] . Over the course of our intervention, the executives realized that going beyond generating financial returns is important because stakeholder inclusion is critical―a burning issue in South Africa. In practical terms, it meant securing the future of their staff to allow them to provide the conditions necessary for their families to flourish in South African society. Discussing the topic during the AR intervention and seeking external advice, the executives decided to launch a new company and set-up an “employee trust”13 to protect their employees’ interests in the eventuality the business is sold. This route was chosen to remedy the side effects the executives witnessed resulting from the sale of their previous company leading to some of their former employees losing their jobs with little or no financial compensation.

Understanding that firms can have a positive societal impact constitutes a first step towards supporting societal goals of a group of executives who would probably not have understood its importance without the AR intervention. This is particularly relevant to the discussion on the limitations of stakeholder theory proposed in section 2. It proves that it is possible for a group of executives to rethink their fundamental understanding of the firm to include societal value in their worldview, even if it was not considered in the first place when developing the company (which was the case for our case studies on Merkur and ABS).

This conclusion has one main limitation. The executives’ willingness to reconsider their business purpose and openness to change may have been encouraged by the conflictual situation they were in at the time of the intervention resulting from the sale of their business to new owners. We therefore feel that there is potential for bias owing to the very specific circumstances within which we conducted the AR intervention. Therefore, the methodology needs to be tested on a larger sample size to confirm whether the results of our study can be replicated or whether they are merely the outcome of the specific conditions in which our research was conducted.

5. Discussion―Addressing a Societal Issue Is Fundamental to Define a Powerful Purpose

From early views of fiduciary duties to recent discussions on the responsibilities of the firm to its stakeholders, the discussion about the purpose of the firm in academic literature has focused on clarifying how to position a company within a larger societal context. As a result, the frameworks proposed either enabled or made sense of models based on delivering positive value to society. To that effect, the most recent view of stakeholder theory―CSV [9] ―suggests transforming societal issues relevant to a firm into business opportunities that can generate financial returns. CSV, despite its success in elevating societal goals to a strategic level, shares the main flaw of earlier views as it is fundamentally anchored in shareholder theory thus defining the success of the firm as one, at least partially, informed by financial value maximization for its shareholders.

Shareholder theory and subsequent views of stakeholder theory have many limitations. First, despite their focus on the need for firms to comply with the law, their common roots in shareholder theory make them at odds with corporate law. This, because from a legal standpoint, shareholders are not the “owners” of a firm and therefore managers cannot be their agents. For example, the law of Delaware defines executives as fiduciaries rather than agents. This difference is important because fiduciaries are obliged to exercise independent judgment to act in the best interests of a firm whereas agents are expected to make discretionary decisions [22] . In addition, approximately 70% of the shares of US-listed companies are held by different types of funds or institutional investors. Those funds are managed by professionals on other people’s behalf and they tend to be rewarded based on the returns they generate on a quarterly basis. This therefore makes it highly unlikely that those professionals will have the same incentive to exercise care in the traditional ownership sense of the term thus leading to high turnover in shares and high frequency trading by speculators [22] . Second, the issue resulting from considering shareholders as the owners of a firm is aggravated by the lack of traditional feature of ownership such as legal liability and responsibility for property for example. With a few exceptions, shareholders are permitted to act in their own interest within the boundaries of securities law. This is against the fundamental precept of the law establishing the notion of rights and responsibilities thus possibly opening the door to malpractice, opportunism and other misuse of corporate assets [22] . Third, the resulting freedom from accountability may make shareholders indifferent to long-term considerations thus affecting the firm’s perspective on what it should focus on [22] . Fourth, there is a fundamental problem with the discussion and criticism of shareholder theory because most of the existing literature assumes shareholder uniformity of purpose. In other terms, it is assumed that all shareholders want firms to maximize their profit thus overlooking the fact that young investors may seek long-term growth, pension funds may seek capital conservations, and other investors may pursue other objectives [22] .

These important limitations set a context to discuss the learnings drawn from our research and introduce an alternative model to stakeholder theory, as follows.

5.1. Self-Regulation as Protective Mechanism

Because it is possible for firms to act unethically while remaining in compliance with legal frameworks, theories of corporate responsibility articulate obligations that go beyond what is required by the law [50] . In this context, we have reviewed two case studies of firms taking an outside-in approach to defining their purpose with the objective of identifying best practices. Despite the small sample size (2 companies) and the limitations presented, we conclude that there is a need for firms pursuing societal objectives to protect themselves against sources of pressure that could divert them from their purpose. This is particularly important when considering shareholder theory and the fact that it has enabled large funds to focus exclusively on buying shares with the purpose of effecting change in companies to maximize shareholders returns, thus affecting the context in which firms operate [22] . In practice, the two banks have decided to self-regulate to address that risk. We conclude however that it is still a challenge to have a perfect set of rules or a flawless compliance monitoring system. Thus, we have highlighted the need for flexibility in the design of protection mechanisms.

5.2. Need for Flexibility

Both ABS and Merkur offer practical examples of the need to redesign mechanisms that have become obsolete over time. In addition, the two case studies serve as examples underlining the challenges associated with the identification of an appropriate level of self-regulation as both banks have gone through lengthy processes to define how much higher than the existing standards they want to aim in order to address societal gaps.

5.3. Is It Possible to Transition from a Business-As-Usual to an Outside-In Type of Firm?

Going beyond learning from the two case studies, we engaged into an AR intervention to test whether working with a firm to anchor an outside-in perspective is possible. Despite the limited sample size of one firm, we conclude that it is possible to change the focus of executives on short-term objectives to considering longer-term goals. In the practical case we discussed, this conclusion was illustrated with the inclusion of stakeholders in the definition of the purpose of the firm with the intent of generating societal value. Our conclusion shares similarities with ABS’ and Merkur’s respective histories given that both organizations started by identifying a societal issue they wanted to address (thus “outside-in”) before designing the firms thought to be the best format to tackle them.

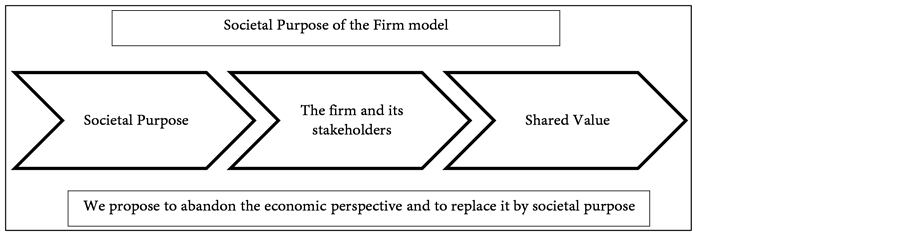

5.4. An Alternative to Stakeholder Theory―The Societal Purpose of the Firm Model

The conclusion presented so far leads us to conceive a new model?The Societal Purpose of the Firm. Unlike Friedman [7] , Freeman [8] and Porter & Kramer’s [9] views, the model we propose redefines the purpose of the firm as one informed by the pursuit of a societal purpose instead of a sole economic purpose. In this model, firms become tools designed to address a societal need identified by using an outside-in approach. The degree to which firms’ goals are moderated by certain opportunities or constraints depends on the specific social reality in which they operate. Our model offers a novel perspective on re-conceptu- alizing the purpose of the firm in which responsible relations to societies is the primary goal and within which economic imperatives only play one part. The two case studies we have presented confirm the model’s viability in a firm context, and the AR intervention illustrates that it is possible to shift executives’ focus towards supporting societal goals.

Figure 4 is proposed as a conceptual framework of our model. It asks firms to start their purpose definition process by taking an outside-in approach. Once a societal problem has been identified, firms adopt a format that will enable them to address the problem they have identified. In this process, they are to engage with their stakeholders to account for their interests. Only then will the firm become a democratically organized multi-stakeholder driven operation that is creating shared value and distributing it fairly.

The next logical question then is to understand the implications our model may have on existing companies and their respective purpose. We did not study this question yet, when looked at from a shared value creation perspective. Adidas or BMW for example are companies that have been successful in implementing CSV projects. However, and because of their respective history and the

Figure 4. The societal purpose of the firm model.

industries they are active in, they still have to address a large quantity of unresolved issues concerning their social value. Practically, and as suggested by Crane, Palazzo, Spence and Matten [10] in an article published in 2014, CSV in its current stage of development may lead to islands of win-win projects in a sea of unsolved societal issues. Our model could provide a solution to addressing them by changing the approach firms adopt to define their purpose.

6. Conclusions

The fundamental question guiding our research was to understand why firms tend to focus on the pursuit of value maximization for their shareholders at the cost of other stakeholders. This is particularly true when we consider that some of the value that is created for shareholders is in fact not created but transferred from other stakeholders at a cost to society in general [22] . Stakeholder theory was proposed as methodology re-conceptualizing the firm as a multi-purpose entity to address this limitation. It embraces the social reality that firms affect and are affected by society, that good management practices account for stakeholder interests, and that their rights provide them with some legitimate stake in how a firm is run. Yet, this stream of literature does not necessarily seek to induce change as it attempts to combine the efficiency of business with the achievement of wider societal objectives. In other words, stakeholder theory offers a solution to integrate various activities into one social strategy yet it fails to offer guidance for a companywide responsible strategy [10] . There is ample proof that this narrow view of the purpose of the firm still prevails in today’s business realm because competing for customers and investors’ interests is the “essence of business” [66] .

While the novel perspectives offered by stakeholder theory serve as examples demonstrating possible evolutions in the field of the purpose of the firm, we propose to abandon the pursuit of purely economic purpose and position firms rather as a tool to address a societal issue as an alternative. The degree to which firms goals are moderated by certain opportunities or constraints depends on the specific social reality in which they operate. Our model offers a novel perspective on re-conceptualizing the purpose of the firm in which responsible relations to society is the primary goal and dealing with the economic imperatives is a residual.

Our research has some limitations resulting from a relatively small sample size and the use of self-reported data. There is therefore a need to test our model on a larger sample size. There will also probably be a significant amount of criticism coming from proponents of the traditional economic view of the firm as they may discount our contribution as being utopic. To those, we respond that the model works as it has been used successfully for more than 30 years by Alternative Bank Schweiz and Merkur Cooperative Bank. Therefore, the question is not to discuss whether it is possible to implement our model. It is more a question of finding firms willing to change.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Aileen Ionescu-Somers, Associate Dean, Business School Lausanne for comments that greatly improved the manuscript.

Cite this paper

Narbel, F. and Muff, K. (2017) Should the Evolution of Stakeholder Theory Be Discontinued Given Its Limitations? Theoretical Economics Letters, 7, 1357-1381. https://doi.org/10.4236/tel.2017.75092

References

- 1. Parmar, B.L., et al. (2010) Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art. Academy of Management Annals, 4, 403-445. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2010.495581

- 2. Levin, C. and Coburn, T. (2011) Wall Street and the Financial Crisis: Anatomy of a Financial Collapse. United States Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Washington DC.

- 3. Clement, R.W. (2005) The Lessons from Stakeholder Theory for U.S. Business Leaders. Business Horizons, 48, 255-264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2004.11.003

- 4. Smith, A. (1904) An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations: Volume One. Liberty Classics, London. https://doi.org/10.1093/oseo/instance.00043218

- 5. Freeman, R.E., Wicks, A.C. and Parmar, B. (2004) Stakeholder Theory and “the Corporate Objective Revisited”. Organization Science, 15, 364-369. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1040.0066

- 6. Kantarelis, D. (2010) Theories of the Firm. Inderscience Enterprise, Geneva.

- 7. Friedman, M. (1970) The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits. The New York Times, New York, 13 September 1970, 122-124.

- 8. Freeman, R.E. (1984) Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Pitman Publishing, Boston.

- 9. Porter, M. and Kramer, M. (2011) Creating Shared Value. Harvard Business Review, 89, 62-77.

- 10. Crane, A., et al. (2014) Contesting the Value of “Creating Shared Value”. California Management Review, 56, 130-153. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2014.56.2.130

- 11. Narbel, F. and Muff, K. (2013) Driving Sustainable Business Implementation through Tripartite Guardianship. Building Sustainable Legacies: The New Frontier of Societal Value Co-Creation, 2013, 46-67. https://doi.org/10.9774/GLEAF.8901.2013.oc.00005

- 12. Dyllick, T. and Muff, K. (2016) Clarifying the Meaning of Sustainable Business: Introducing a Typology from Business-as-Usual to True Business Sustainability. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, 156-174. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026615575176

- 13. Barnard, C. (1938) The Functions of the Executive. Harvard University Press, London.

- 14. Mazutis, D. and Ionescu-Somers, A. (2015) How Authentic Is Your Corporate Purpose? IMD Global Center for Sustainability Leadership, Lausanne.

- 15. Collins, J. and Porras, J.I. (1994) Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies. Harper Collins Publishing, New York.

- 16. Ellsworth, R.R. (2002) Leading with Purpose: The New Corporate Realities. Stanford University Press, Stanford.

- 17. Binney, G. (2006) Corporate Purpose and Values: Time for a Rethink? Tomorrow’s Company, London.

- 18. Freeman, R.E. (1994) The Politics of Stakeholder Theory. Business Ethics Quarterly, 4, 409-421. https://doi.org/10.2307/3857340

- 19. Boschbadia, M.T., Montillor-Serrats, J. and Tarrazon, M.A. (2013) Corporate Social Responsibility from Friedman to Porter and Kramer. Theoretical Economics Letters, 3, 11-15. https://doi.org/10.4236/tel.2013.33A003

- 20. Goll, I. and Rasheed, A.A. (2004) The Moderating Effect of Environmental Munificence and Dynamism on the Relationship between Discretionary Social Responsibility and Firm Performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 49, 41-54. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BUSI.0000013862.14941.4e

- 21. Vasséi, M., Monetarism, A., Faccarello, G. and Kurz, H.D. (2016) Handbook on the History of Economic Analysis, Volume II: Schools of Thought in Economics. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, 375-390.

- 22. Bower, J.L. and Paine, L.S. (2017) The Error at the Heart of Corporate Leadership. Harvard Business Review, 95, 50-60.

- 23. Jensen, M.C. and Meckling, W.H. (1976) Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3, 305-360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

- 24. Stout, L.A. (2013) The Toxic Side Effects of Shareholder Primacy. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 161, 2003-2023.

- 25. Dallas, L. (2011) Short-Termism, the Financial Crisis, and Corporate Governance. Social Science Electronic Publishing, 266-361.

- 26. Rappaport, A. (2005) The Economics of Short-Term Performance Obsession. Financial Analysts Journal, 61, 65-79. https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v61.n3.2729

- 27. Kedzior, J. and Rozkrut, M. (2014) Short-Termism in Business: Causes, Mechanisms and Consequences. EYGM Limited, Poland.

- 28. Sundaram, A. and Inkpen, A. (2004) The Corporate Objective Revisited. Organizational Science, 15, 350-363. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1040.0068

- 29. Bowie, N.E. (2017) Business Ethics: A Kantian Perspective. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316343210

- 30. Richardson, V.J. (2000) Information Asymmetry & Earnings Management: Some Evidence. Review of Quantitative Finance & Accounting, 15, 325-347. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012098407706

- 31. Margolis, J.D. and Walsh, J.P. (2001) People and Profits? The Search for a Link between a Company’s Social and Financial Performance. Psychology Press, Hove.

- 32. Jones, T.M. and Wicks, A.C. (1999) Convergent Stakeholder Theory. Academy of Management Review, 24, 404-437.

- 33. Blattberg, C. (2004) From Pluralist to Patriotic Politics: Putting Practice First. Oxford University Press, New York.

- 34. Mansell, S. (2013) Capitalism, Corporations and the Social Contract: A Critique of Stakeholder Theory. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139058926

- 35. Porter, M.E. and Kramer, M.R. (1999) Philanthropy’s New Agenda: Creating Shared Value. Harvard Business Review, 77, 121-131.

- 36. Porter, M.E. and Kramer, M.R. (2002) The Competitive Advantage of Corporate Philanthropy. Harvard Business Review, 80, 56-68.

- 37. Porter, M.E. and Kramer, M.R. (2006) Strategy and Society: The Link between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility. Harvard Business Review, 84, 78-92.

- 38. Donaldson, T. and Dunfee, T.W. (199) Ties that Bind: A Social Contracts Approach to Business Ethics. Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

- 39. Fombrun, C., Gardberg, N. and Branett, M. (2000) Opportunity Platforms and Safety Nets: Corporate Citizenship and Reputational Risk. Business and Society Review, 105, 85-106. https://doi.org/10.1111/0045-3609.00066

- 40. Spar, D. and La Mure, L. (2003) The Power of Activism: Assessing the Impact of NGO on Global Business. California Management Review, 45, 78-101. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166177

- 41. Matten, D. and Crane, A. (2005) Corporate Citizenship: Toward and Extended Theoretical Conceptualization. Academy of Management Review, 30, 166-179. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2005.15281448

- 42. Scherer, A.G. and Palazzo, G. (2011) The New Political Role of Business in a Globalized World: A Review of a New Perspective on CSR and Its Implications for the FIrm, Governance and Democracy. Journal of Management Studies, 48, 899-931. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00950.x

- 43. Albareda, L., Lozano, J. and Ysa, T. (2007) Public Policies on Corporate Social Responsibility: The Role of Governments in Europe. Journal of Business Ethics, 74, 391-407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9514-1

- 44. Gond, J.P., Kang, N. and Moon, J. (2011) The Government of Self Regulation: On the Comparative Dynamics of Corporate Social Responsibility. Economy and Society, 40, 640-671. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2011.607364

- 45. Porter, M.E. (2008) The Five Competitive Forces that Shape Strategy. Harvard Business Review, 86, 79-93.

- 46. Butler, H.N. (1996) Externalities and the Matching Principle: The Case for Reallocating Environmental Regulatory Authority. Yale Law School Legal Scholarship Repository, 14, 23-66.

- 47. Jackson, J.K. (2010) Financial Market Supervision: European Perspectives. Diane Publishing, Collingdale.

- 48. Omarova, S.T. (2012) Bankers, Bureaucrats, and Guardians: Toward Tripartism in Financial Services Regulation. Journal of Corporation Law, 37, 622-658.

- 49. Laffont, J.J. and Tirole, J. (1991) The Politics of Government Decision-Making: A Theory of Regulatory Capture. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106, 1089-1127. https://doi.org/10.2307/2937958

- 50. Norman, W. (2011) Business Ethics as Self-Regulation: Why Principles that Ground Regulations Should Be Used to Ground Beyond-Compliance Norms as Well. Journal of Business Ethics, 102, 43-57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1193-2

- 51. Heath, J. (2007) An Adversarial Ethic for Business: Or When Sun-Tzu Met the Stakeholder. Journal of Business Ethics, 72, 359-374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9175-5

- 52. Organisation for Economic Co-Operative and Development (2015) Industry Self-Regulation: Role and Use in Supporting Consumer Interests. Organisation for Economic Co-Operative and Development, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/5js4k1fjqkwh-en

- 53. Narbel, F. (2015) Alternative Bank Schweiz AG: A Banking Model for the Future. Building Sustainable Legacies: The New Frontier of Societal Value Co-Creation, 2015, 12-40. https://doi.org/10.9774/GLEAF.8901.2015.de.00003

- 54. Narbel, F. (2016) Merkur Cooperative Bank. Building Sustainable Legacies. (Unpublished)

- 55. Plano Clark, V.L., Gutmann, M.L. and Hanson, W.E. (2003) Advanced Mixed Methods Research Designs. In: John, W.C., Ed., Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research, SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, 209-240.

- 56. Miller Consultants (2016) Sustainability Culture and Leadership Assessment Pilot. http://www.millerconsultants.com http://millerconsultants.com/sustainability-culture-and-leadership-assessment-pilot/

- 57. Kahn, C. and Winton, A. (1998) Ownership Structure, Speculation, and Shareholder Intervention. The Journal of Finance, 53, 99-129. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.45483

- 58. Crompton, S.W. (2007) Desmond Tutu: Fighting Apartheid. Chelsea House Publishers, New York.

- 59. Irwin, J. (2011) Doing Business in South Africa: An Overview of Ethical Aspects. Institute of Business Ethics, London.

- 60. Heron, J and Reason, P. (2006) The Practice of Co-Operative Inquiry: Research “with” Rather than “on” People. In: Reason, P. and Bradbury, H., Eds., Handbook of Action Research, SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, 144-154.

- 61. Bergold, J. and Stefan, T. (2012) Participatory Research Methods: A Methodological Approach in Motion. Historial Social Research, 37, 191-222.

- 62. Bradbury, H., Roth, G. and Gearty, M. (2015) The Practice of Learning History: Local and Open System Approaches. Hilary, B., Ed., The Sage Handbook of Action Research, SAGE Publications, London, 83-85. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473921290.n3

- 63. McNiff, J. and Whitehead, J. (2011) Evaluation Your Research. In: McNiff, J. and Whitehead, J., Eds., All You Need to Know about Action Research, SAGE Publications, London, 83-90.

- 64. Narbel, F. (2016) Corporate Finance as an Action Research Domain: From Regulations to Self-Regulations. (Unpublished)

- 65. Collins, M. and Parsa, H.G. (2006) Pricing Strategies to Maximize Revenues in the Lodging Industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 25, 91-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2004.12.009

- 66. Simons, R.L. (2013) The Business of Business Schools: Restoring a Focus on Competing to Win. Capitalism and Society, 8, 1-37.

- 67. Merkur Cooperative Bank (2014) Annual Report 2014. Merkur Cooperative Bank, Copenhagen.

- 68. Elkington, J. (1997) Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business. Capstone, Oxford.

- 69. Trading Economics (2017) South Africa Unemployment Rate. http://www.tradingeconomics.com/south-africa/unemployment-rate

NOTES

1See reference [1] for example.

2The Five Forces analysis is a framework identifying an industry’s strengths and weaknesses to develop a firm’s strategy.

3A situation in which the allocation of goods and services is not efficient.

4Because the choice of methodologies was part of a sequence of exploratory research, the discussion of methodologies in sections 3 and 4 focuses on the add-ons that enabled us to go further into our research instead of discussing the relevance of case studies (Phase 1) and Action Research (phase 2) as methodologies.

5The Triple Bottom Line is an accounting framework adopted by many organizations to evaluate their performance against social, environmental and financial metrics [68] .

6Alternative Bank Schweiz (ABS) is a joint stock company based in Switzerland. It was incorporated in 1990 and had a balance sheet of CHF 1.4 billion at the end of 2013 [53] .

7Merkur is a cooperative bank. It was incorporated in 1982 and had a balance sheet of DKK 1.4 billion (approximately CHF 210 million) by the end of 2014 [67] .

8We hypothesize that the higher response rates are the result of involving the banks’ upper management in the survey distribution process thus resulting in generating more attention and interest for the research.

9ABS created a working group comprising 1,600 members and 120 organizations allowing it to account for the interests of the largest possible number of stakeholders [53] .

10The equity ratio measures the proportion of assets financed by shareholders as opposed to creditors.

11The Institute for Business Ethics focuses on research and teaching in the field of business ethics.

1226.5 percent of the workforce was unemployed at the end of 2016 [69] .

13A trust is set up for the employees’ benefits. In this case, the company the grantor and the employees are the beneficiaries of its activities.