Sociology Mind 2012. Vol.2, No.3, 272-281 Published Online July 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/sm) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/sm.2012.23036 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 272 Determinants of Individual Trust in Global Institutions: The Role of Social Capital and Transnational Identity Harris H. Kim Department of Sociology, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, South Korea Email: harrishkim@ewha.ac.kr Received March 21st, 2012; revised April 25th, 2012; accepted May 28th, 2012 The focus of this paper is to examine the determinants of individual-level trust in global institutional ac- tors, namely the World Bank, the World Trade Organization, and multinational corporations (MNCs). This study is guided by two lines of inquiry. First, consistent with the social capital theory, it investigates the role of social or generalized trust in creating institutional trust. Second, in keeping with the extant lit- erature on economic and cultural globalization, it also probes into how and to what extent transnational identity shapes people’s perception and evaluation of international organizations. Based on the Asian Ba- rometer Survey (2003), a cross-national dataset covering 10 Asian countries (N = 8086), this study finds that both factors significantly shape the level of institutional trust, while controlling for a host of relevant variables. More specifically, logistic regression analyses reveal that the tendency to trust generalized oth- ers has a positive association with the degree of trust placed in institutional actors. Transnational identity, on the contrary, has the reverse effect. The implications of the empirical findings and the suggestions for future research are discussed. Keywords: Generalized Trust; Social Capital; Institutional Trust; Transnational Identity; Globalization Social Capital and Institutional Trust Where does institutional trust come from? That is, what are some of the key factors that influence individuals to place their trust in institutional actors (e.g., courts, governments, busi- nesses, international regulatory bodies)? This question has been addressed by many concerned academics. In particular, political scientists have had much to say about it. Perhaps the most well-known theoretical statement on this issue comes from Robert Putnam (1993, 2000) and his work on the positive role of social capital (i.e., generalized trust) on the workings of de- mocratic institutions. In his oft-quoted study on the civic tradi- tions in Italy, Putnam (1993) observes that: “In all societies, to summarize our argument so far, dilemmas of collective action hamper attempts to cooperate for mutual benefit, whether in politics or in economics. Third-party en- forcement is an inadequate solution to this problem. Voluntary cooperation (like rotating credit associations) depends on social capital. Norms of generalized reciprocity [for favors received] and networks of civic engagement encourage social trust and cooperation because they reduce incentives to defect, reduce uncertainty, and provide models for future cooperation. Trust itself is an emergent property of the social system, as much as a personal attribute. Individuals are able to be trusting (and not merely gullible) because of the social norms and networks within which their actions are embedded” (177). In short, social capital of a community is crucial since it al- lows the members to encourage voluntary cooperation, mini- mize free riding, and facilitate collective action. More impor- tantly, according to Putnam, this aspect of communal life is a necessary prerequisite for political institutions to function properly. Trust, norms of reciprocity, and networks of civic engagement are in fact valuable ingredients that lubricate the democratic machinery, as the argument goes. Why and how does healthy associational life lead to benefi- cial political outcomes? In light of Putnam’s seminal work, much research has been conducted particularly to test the causal relationship between the individual-level social capital and the amount of trust people have in their political leaders and insti- tutions (see, e.g., Brehm & Rahn, 1997; Keele, 2007; Paxton, 2002; Rothstein & Uslaner, 2005; Zmerli & Newton, 2008). The gist of the argument is that trusting behavior in the social arena translates into (or “spills over”) the political realm in terms of individual political engagement. According to social capital theory, generalized trust is recognized as one of the most critical forms of resource that can “act as the foundation for stable and effective democratic government” (Zmerli & Newton, 2008: p. 706). Citizens who are withdrawn from civic engagement tend to experience a sense of estrangement, pow- erlessness, and distrust. In short, those who pull away from associational life suffer from the deficiency of social capital, which they project onto government institutions (Keele, 2007). As Rothenstein and Uslaner (2005: p. 41) put it, “people who believe that in general most other people in their society can be trusted are also more inclined to have a positive view of their democratic institutions, to participate more in politics, and to be more active in civic organizations”. A substantial literature exists highlighting how generalized social trust provides a solid basis for stable and effective de- mocratic government by increasing people’s level of confi- dence in political institutions. Using a large cross-national dataset, for example, Paxton (2002) shows that voluntary asso- ciation memberships and generalized trust are positively related to democratization at the aggregate level. Zmerli and Newton (2008) extend their earlier research by examining the relation- ship between generalized social trust, political trust, and satis-  H. H. KIM faction with democracy. Their analysis based on European Social Survey and the US CID reveals solid evidence illustrat- ing the link between social trust and political confidence and political support across 23 European countries and the US. In one of the earlier and oft-quoted studies, using the General Social Survey, Brehm and Rahn (1997) also demonstrate the causal impact of interpersonal trust and civic engagement on people’s confidence in democratic institutions. Similar findings are reported by Denters, Gabriel, and Torcal (2007) in their examination of political confidence in the context of European democracies. More theoretically informed writings also suggest that there is a close association between generalized trust and political or institutional trust (see e.g., Braithwaite & Levi, 1998; Dekker & Uslaner, 2001; Gambetta, 1988; Inglehart, 1997; Nooteboom, 2007; Seligman, 1997; Sztompka, 2000; Uslaner, 2002). Despite the voluminous literature on this topic, however, there is still an ongoing controversy concerning the exact link- age between social/generalized trust and political/institutional trust (see, e.g., Delhey & Newton, 2003; Mishler & Rose, 2005; Newton & Norris, 2000; Rothstein, 2002). Zmerli and Newton (2008) correctly point out that indeed this has been an intellec- tually contested area, where some researchers find empirical support for the causal connection while others fail to do so. According to another author, “there are patchy and weak asso- ciations between social and political trust” (Newton, 2001: p. 202). Based on the results from estimating a structural equation model using the New Russia Barometer survey data, Mishler and Rose (2005) similarly conclude that “trust has small if any independent effect on support for the current regime” (14). In a more recent article, Jamal and Nooruddin (2010) contend that the “democratic utility of trust” is not uniform across the globe but that it interacts with the degree of democracy within each country. More specifically, individual-level generalized trust is found to be linked with political support but only for those living in democratic countries. These and other studies under- score an important fact in the existing scholarship: the causality surrounding social capital (primarily conceptualized in terms of generalized trust) and institutional trust remains moot. The purpose of the present study is two-fold. First, it seeks to shed empirical light on the debate by examining a large cross-national dataset. Even a cursory review of the literature shows that the vast majority of the previous work focuses on domestic political institutions such as the local government, the police, and the legal system (e.g., Edlund, 2006; Johnson, 2005; Kim, 2005; Letki, 2006; Rahn & Rudolph, 2005). In light of this trend, this study shifts the analytical angle by focusing on a set of global institutions, namely the World Bank, the World Trade Organization (WTO), and multinational corporations (MNCs). The main research question is thus directed at the extent to which varying degrees of generalized trust relate to people’s respective evaluation of organizations that operate beyond national borders, a topic that has not received much attention in the past. In addition to the empirical contribution, this study also in- corporates a new causal factor in explaining individual percep- tion and evaluation of the afore-mentioned international or- ganizations, namely transnational identity. Previous research mostly focus on “contextual and individual-level sources of local political trust” (Rahn & Rudolph, 2005: p. 530). The for- mer category includes variables like national income inequality, racial composition, urban/rural divide, town size, etc. The latter contains individual-level attributes and attitudes such as age, race, education, gender, political beliefs, and social values. In this study, some of these factors are also included in the quan- titative analysis but only as control variables in order to test whether transnational identity influences the degree to which individual actors view international organizations. With increasing globalization, the subjective notion of self- identity is becoming uprooted and transplanted across local boundaries. The gradual erosion of national identities and the rise of “cosmopolitan citizenship” have been observed as the hallmarks of economic globalization (Berger & Huntington, 2002; Huntington, 1996; Norris, 2000). According to Hunting- ton’s (1993) original thesis concerning the “clash of civiliza- tions”, the great divisions and international conflicts in the post-Cold War era are cultural, not ideological. Cultural con- flicts will take place among nine major civilizations, as he pre- dicts, according to which new regional identities will form that transcend national territories and state boundaries. These new forms of identity and concomitant value shifts, as well as cul- tural conflicts, in the face of modernization and globalization have been the focus of much research (Appadurai, 2000; Applbaum, 2000; Hsiao, 2002; Inglehart & Welzel, 2005; Leiber & Weisberg, 2002; Rosendorf, 2000; Srivinas, 2002; Sum, 2000). Based on the analysis of the World Values Surveys, Norris (2000) specifically points out that what he calls “global iden- tity” has increased over the last several decades. As he shows, cosmopolitan attitudes such as those in favor of free trade and international organizations (such as the United Nations), for example, have also risen. In their comprehensive cross-national study based on the European Values Study Eurobarometer sur- veys, Arts and Halman (2006) complement this view by show- ing that national identification has declined over the years throughout most European countries and that there has been a growing sense of attachment to transnational identity. In a re- lated study, Knovich (2009) shows how the content of identity has important implications for people’s domestic and foreign policy preferences. The key point is that identity—whether locally, regionally, nationally, or internationally based—has grave consequences on how people view social, economic, and political issues, which are becoming increasingly more subject to the forces of globalization. Given that the World Bank, the WTO, and MNCs are three major institutional actors that sym- bolize and embody (economic) globalization, it is relevant to inquire about how the emergence of transnational identity, itself a product of (cultural) globalization, contributes to the dynam- ics of institutional trust conceptualized at the individual level. In sum, the empirical analysis in this paper is informed by two related inquiries. First, what is the causal impact, if any, of trusting generalized others on people’s subjective evaluation of global institutional actors, while controlling for other relevant factors? The literature has shown that the link between general- ized trust and political trust is, for the most part, positive. Does a similar causal relationship hold between trusting generalized others and having confidence in global institutions? Second, ceteris paribus, how does the acquisition of a transnational identity (a sense of belonging to or affiliation with a geographic region larger than one’s own country of birth or nationality) affect the level of institutional trust held by individuals? Are people with a transnational affiliation more or less likely to view the agents of economic globalization as being trustworthy? The remainder of this paper is devoted to answering these ques- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 273  H. H. KIM tions by analyzing a dataset that provides a wealth of compara- tive information on some of the major Asian countries. The next section describes the data and the methods of variable measurement and analysis. It will be followed by the interpreta- tion of the findings and the discussion concerning their impli- cations. The concluding section offers some broad implications concerning the research on social capital and institutional trust as well as possible directions for future research. Data and Measurement The data analyzed for this study is the first wave of the Asian Barometer Survey (2003), which contains probability samples from ten countries including Japan, South Korea, China, Ma- laysia, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, India, Sri Lanka, and Uz- bekistan. The Asian Barometer Survey is headquartered in Taipei and co-hosted by the Institute of Political Science, Aca- demia Sinica and The Institute for the Advanced Studies of Humanities and Social Sciences, National Taiwan University. The survey collects general information on people’s political attitudes and beliefs as well as social values in the context of globalization. The data were gathered through face-to-face interviews with randomly selected samples of respondents rep- resenting the adult population in each country. Roughly 8000 subjects were interviewed in each country, resulting in the total sample size of 8086. The dataset was released to the author by the Department of Political Science at National Taiwan Univer- sity with permission to use it for academic purposes. Dependent Variable There are three dependent variables to measure institutional trust (TRUST_WB, TRUST_WTO, TRUST_MNC). In the questionnaire, the respondents were asked about their subjec- tive assessment of various political, economic, for-profit, and non-governmental institutions, including both domestic foreign. The exact wording is: “Please indicate to what extent you trust the following institutions to operate in the best interests of so- ciety. If you don’t know what to reply or have no particular opinion, please say so.” The answer choices include: “Trust a lot” (=“4”), Trust to a degree” (=“3”), “Don’t really trust” (=“2”), and “Don’t trust at all” (=“1”). Based on the answers provided, a four-point scale was created for each of the three dependent variables. Some answered “Don’t Know,” which were taken care of as missing cases and hence omitted from the analysis; 18.6% gave this answer when evaluating the World Bank, 19.4% for the WTO, and 12.8% for MNCs. Independent Variab le s To address the main questions stated above that guide the empirical inquiry, two separate independent variables are cre- ated, one for generalized trust and another for transnational identity. The question for the generalized trust variable (GEN_TRUST) used in the analysis as stated in the Asian Ba- rometer Survey is as follows: “Do you think that people generally try to be helpful or do you think that they mostly look out for themselves?” 1) People generally try to be helpful 2) People mostly look out for themselves 3) Don’t know This question is similar to the standard measures found in the World Values Survey (WVS) and the European Values Survey (EVS), as analyzed by Inglehart and Welzel (2005) and many others, after which the ABS is designed (see e.g., Zmerli and Newton (2008: p. 709) for a discussion on the use of this par- ticular and other related variables). Based on the answers given, a dichotomous variable is created, where it is coded “1” if the respondent picked the first answer choice (“People generally try to be helpful”) and “0” otherwise. The “Don’t know” option is treated as a case of missing values. The transnational identity variable (TRANS_ID) is con- structed from the information gathered from the following question in the survey: “Throughout the world, some people also see themselves as belonging to a transnational group (such as Asian, people of Chinese ethnicity, people who speak the same language or practice the same religion). Do you identify with any transna- tional group? 1) Asian 2) Other transnational identity (please specify) 3) No, I don’t identify particularly with any transnational group A binary coding scheme is used to assign a value of “1” to the first option (“Asian”) and “0” otherwise. Since the countries in the dataset belong to a broad regional category called Asia, only those respondents who identify themselves as being “Asian” were given the value of “1”. The reference category consists of the rest who chose either 2 or 3 as the answer to the question. 59.7% of the sample considered themselves as be- longing to a transnational category called “Asian”. Control Variables A number of additional variables are used in the analysis as controls, which are causally related to the outcome variables that measure institutional trust. They include individual-level socioeconomic and demographic factors such as each respon- dent’s age (AGE), religion, gender (MALE = “1”), marital status (MARRIED = “1”), educational level, ability to speak English, ethnic pride, and living standards (i.e., subjective as- sessment of one’s socioeconomic status). Descriptive statistics reveal that the average age of the entire sample is 37. 49.2 per- cent of the survey participants were men, and 69.4 percent in the dataset are married. As for the educational levels, 1.5 per- cent of the sample have no formal schooling. About a third (33.6%) of them are high school graduates, and 19.3 percent have a college degree. The education variable (EDUC) was created using a 6-point scale (1 = “no schooling”; 2 = “middle school”; 3 = “high school”; 4 = “vocational-technical school”; 5 = “professional school”; 6 = “university and graduate school”). The variable for living standards (SES) is measured using a 5-point scale (e.g., 1 = “Low,” 3 = “Average,” 5 = “High”). About 3 percent of the sample identify themselves as being members of the “low” class, compared with 68.7 percent who see themselves as belonging to the “middle” (average) class while 12 percent claim to be part of the “high” class. When it comes to the religious background, Christians make up 8.8 percent of the sample (3.3% Catholics and 5.5% Protestants). Muslims make up 15.7 percent of the sample, Hindus consist of 10.7 percent, and the largest group is the Buddhist with 36.9 percent. These groups add up to about 72 percent of the entire dataset. The remaining group includes “other” minor religions (e.g., Confucianism, Taoism, Sikh, Jewish) as well as atheists. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 274  H. H. KIM In the analysis, three dummy variables are included, namely CATHOLIC, PROTESTANT, and MUSLIM. The omitted baseline group includes the rest. In addition to the religious category, another variable (RELIGIOSITY) is also measured to account for their religious participation (“Apart from weddings, funerals and such ceremonies, about how often do you attend religious services or visit a place of worship these days?”). This variable is constructed using a 7-point scale ranging from “never” (=1) to “twice a week” (=7). The variables discussed up to now are standard measures based on the respondents’ socio-demographic information. Three additional variables are taken into account that gauge different levels of ethnic pride (ETH_PRIDE) foreign language skills (ENGLISH) and international exposure (INT_EXP). In an increasingly globalizing world, international regulatory bodies and multinational businesses can powerfully shape the life chances of individuals and even the fate of nations. In fact, the process of economic globalization driven by such institutions as the WB, the WTO and the MNCs are known to have grave domestic consequences such as compromising state sovereignty, exacerbating inequality, and uprooting traditional ways of life (see e.g., Lechner & Boli, 2000; Nye & Donahue, 2000; Sassen, 1998; Smith, Solinger, & Topik, 1999). Hence, it is reasonable to expect that whether or not people hold a favorable view of (or “trusts”) global economic institutional actors is shaped by their attitude toward their own ethnicity or nationality. In the dataset, a significant proportion of those surveyed (61.5%) are “very proud” of their ethnicity, while 25.9 percent are “some- what” proud of their ethnicity. The coding scheme for this variable is as follows: 4 = “Very proud”, 3 = “Somewhat proud”, 2 = “Not really proud”, 1 = “Not proud at all”. How “globalized” a person is can also have an impact on how that individual perceives and evaluates global institutions. To account for this, the individual respondent’s ability to speak English and how often one has travelled abroad are controlled for. The language variable (ENGLISH) is coded as follows: 1 = “not at all”, 2 = “very little”, 3 = “I can speak English well enough to get by in daily life”, 4 = “I can speak English very fluently”. The English ability is an important proxy for indi- vidual-level globalization. To the extent that a person speaks English well, s/he can be seen as being more cosmopolitan or open-minded. And having a cosmopolitan outlook is highly related to how the person feels about global issues and interna- tional organizations (Norris, 2000). Hence, it is important to include this measure in the analysis in testing the causal effects of generalized trust on the outcome variables. In the dataset, 5.9 percent claim to speak English “very fluently,” whereas a sig- nificantly higher proportion (37.8%) does not speak it “at all.” The variable GLOB_EXP is constructed based on the following statement: “I have traveled abroad at least three times in the past three years, on holiday or for business purposes”. It is a dichotomous variable (“Yes” = 1). About 7% of the sample gave an affirmative answer to the statement. In addition, two attitudinal variables are measured. In the survey, the subjects were asked to identify items from a list of social and economic issues they consider to be worrisome. The exact wording is: “Which, if any, of the following issues cause you great worry?” Among the list are two topics that are rele- vant to this analysis, namely “economic problems in your country” and “globalization”. Based on the answers given (“Worry” = 1; “Not mentioned” = 0), the two dichotomous variables ECON_WORRY and GLOB_WORRY are created. In the survey, because of the politically sensitive nature of the question, the subjects living in Myanmar were not asked about certain issues they worry about, including the domestic eco- nomic situation and globalization. Hence, the quantitative find- ings reported below are based on a subset of the original data that excludes those respondents who were originally surveyed in this specific country. Lastly, two country-level variables are taken into consideration to control for macro-level effects. One is the (natural log of) GDP per capita for each of the nations in the sample. The other is the dummy variable named EAST_ ASIA. Respondents who live in Japan, Korea, and China are given the value of “1” while the rest are assigned “0”. The descriptive statistics for all the variables mentioned are shown in Table 1. Table 2 contains the bivariate correlation matrix. Since the dependent variables are all categorically dis- tributed, nominal logistic regression models are estimated. Ta- bles 3-5 consist of the findings from the analyses, each table corresponding to one of the three dependent variables regressed on the independent and control variables. The following section describes the regression results and their interpretations. Statistical Findings Table 3 contains the regression coefficients from estimating Table 1. Descriptive statistics. Min Max Mean Std. Dev. TRUST_WB 1.00 4.00 2.8403 .8151 TRUST_WTO 1.00 4.00 2.7690 .7794 TRUST_MNC 1.00 4.00 2.5212 .7968 GEN_TRUST 0 1.00 .3530 .4779 TRANS_ID 0 1.00 .5973 .4904 AGE 20.00 59.00 36.8682 10.8922 MALE 0 1.00 .4920 .4999 MARRIED 0 1.00 .6942 .4607 EDUC 1.00 6.00 3.7020 1.5076 SES 1.00 5.00 2.9927 .7154 CATHOLIC 0 1.00 .0328 .1780 PROTESTANT 0 1.00 .0553 .2285 MUSLIM 0 1.00 .1566 .3634 RELIGIOSITY 1.00 7.00 4.2830 1.9245 ETHN_PRIDE 1.00 4.00 3.4755 .7719 ENGLISH 1.00 4.00 1.9092 .9127 INT_EXP 0 1.00 .0696 .2545 GLOB_WORRY 0 1.00 .0568 .2314 ECON_WORRY 0 1.00 .3100 .4630 GDP_PER 5.28 10.41 7.371 1.569 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 275  H. H. KIM Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 276 Table 2. Correlation matrix. (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) 1. TRUST_WB 1 .726** .372** −.071** −.037** −.045** −.058** .042** .006 −.055** 2. TRUST_WTO .726** 1 .373** −.077** −.034** −.046** −.049** .049** .010 −.037** 3. TRUST_MNC .372** .373** 1 −.085** −.027* −.059** −.048** .039** .018 −.028* 4. AGE −.071** −.077** −.085** 1 −.003 .441** −.165** −.096** .001 .001 5. MALE −.037** −.034** −.027* −.003 1 −.056** .070** −.030** −.009 −.031** 6. MARRIED −.045** −.046** −.059** .441** −.056** 1 −.145** .011 −.021 −.034** 7. EDUC −.058** −.049** −.048** −.165** .070** −.145** 1 .124** −.001 .070** 8. SES .042** .049** .039** −.096** −.030** .011 .124** 1 .048** −.060** 9. CATHOLIC .006 .010 .018 .001 −.009 −.021 −.001 .048** 1 −.045** 10. PROTESTANT −.055** −.037** −.028* .001 −.031** −.034** .070** −.060** −.045** 1 11. MUSLIM .011 −.002 .146** −.044** .000 .016 −.010 .003 −.079** −.104** 12. RELIGIOSITY .026* .003 .003 −.011 .011 −.018 .049** −.136** −.182** −.147** 13. ETHN_PRIDE .108** .103** .082** −.023* .012 .019 −.093** .178** .004 −.176** 14. ENGLISH .002 .009 .014 −.174** .076** −.144** .421** .214** .070** −.009 15. INT_EXP −.015 −.001 −.003 .025* .035** .012 .125** .069** .021 .078** 16. GLOB_WORRY .031* .012 .038** −.040** .043** −.031** .015 .023* −.018 −.022* 17. ECON_WORRY .008 −.004 .033** −.001 .021 .002 .003 −.069** −.012 .013 18. GDP_PER −.269** −.209** −.218** .136** −.015 .038** .067** −.121** −.024* .008 19. GEN_TRUST .068** .073** .068** .045** −.021 .055** −.084** .045** −.008 −.002 20. TRANS_ID −.049** −.031* −.077** −.052** .001 −.033** −.028* .029* .070** −.034** (11) (12) (13) (14) (15) (16) (17) (18) (19) 1. TRUST_WB .026* .108** .002 −.015 .031* .008 −.269** .068** −.049** 2. TRUST_WTO .003 .103** .009 −.001 .012 −.004 −.209** .073** −.031* 3. TRUST_MNC .003 .082** .014 −.003 .038** .033** −.218** .068** −.077** 4. AGE −.011 −.023* −.174** .025* −.040** −.001 .136** .045** −.052** 5. MALE .011 .012 .076** .035** .043** .021 −.015 −.021 .001 6. MARRIED −.018 .019 −.144** .012 −.031** .002 .038** .055** −.033** 7. EDUC .049** −.093** .421** .125** .015 .003 .067** −.084** −.028* 8. SES −.136** .178** .214** .069** .023* −.069** −.121** .045** .029* 9. CATHOLIC −.182** .004 .070** .021 −.018 −.012 −.024* −.008 .070** 10. PROTESTANT −.147** −.176** −.009 .078** −.022* .013 .008 −.002 −.034** 11. MUSLIM −.143** .085** −.050** .033** .086** .091** −.169** −.003 .105** 12. RELIGIOSITY 1 −.222** −.120** −.009 −.035** −.005 .181** .065** −.176** 13. ETHN_PRIDE −.222** 1 .069** −.075** .052** −.009 −.319** .070** .117** 14. ENGLISH −.120** .069** 1 .112** .058** .005 −.071** −.027* −.043** 15. INT_EXP −.009 −.075** .112** 1 .002 −.001 .064** −.001 .026* 16. GLOB_WORRY −.035** .052** .058** .002 1 .189** −.059** .018 −.015 17. ECON_WORRY −.005 −.009 .005 −.001 .189** 1 −.063** .018 −.018 18. GDP_PER .181** −.319** −.071** .064** −.059** −.063** 1 −.015 −.046** 19. GEN_TRUST .065** .070** −.027* −.001 .018 .018 −.015 1 −.042** 20. TRANS_ID −.176** .117** −.043** .026* −.015 −.018 −.046** −.042** 1  H. H. KIM Table 3. Logistic coefficients from regressing TRUST_WB on selected independent and control variables. Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Estimate S.E. Estimate S.E. Estimate S.E. Estimate S.E. AGE −.004 .003 −.004 .003 −.005 .003 −.005 .003 MALE −.120* .047 −.116* .048 −.114* .048 −.111* .049 MARRIED −.141* .058 −.157** .058 −.145* .059 −.161** .059 EDUC −.056** .018 −.051** .018 −.060** .018 −.055** .018 SES .056 .035 .051 .035 .049 .036 .043 .036 CATHOLIC .130 .130 .146 .131 .193 .131 .211 .132 PROTESTANT −.167 .108 −.181 .109 −.152 .109 −.165 .110 MUSLIM −.110 .069 −.124 .069 −.090 .069 −.103 .070 RELIGIOSITY .074*** .015 .071*** .015 .072*** .015 .068*** .015 ETHNIC_PRIDE .105** .035 .092** .035 .114** .036 .102** .036 ENGLISH .001 .030 −.002 .030 −.007 .030 −.010 .030 INT_EXP .085 .093 .075 .094 .138 .095 .127 .096 GLOB_WORRY .215* .101 .205* .101 .204* .101 .196 .102 ECON_WORRY −.001 .022 −.005 .022 −.006 .022 −.010 .022 GDP_PER −.295*** .018 −.294*** .022 −.297*** −.299*** −.010 .023 EAST_ASIA −.084 .078 −.127 .080 −.184* .082 −.227** .084 GEN_TRUST .236 .051*** .238*** .052 TRANS_ID −.282*** .052 −.285*** .052 INTERCEPT1 −2.180*** −2.222*** −2.421*** −2.471*** INTERCEPT2 −.118 −.163 −.420 −.472* INTERCEPT3 2.556*** 2.527*** 2.273*** 2.237*** −2 LL 15758.57 15528.29 15147.47 14955.789 N 6984 6906 6693 6616 Note: *<.05; **<.01; ***<.001. the effects of the independent and control variables on the re- spondents’ trust in the World Bank. Model 1 is the baseline model containing only the controls. Several of them reach the level of significance. Among the individual-level attributes, those who are male, married and have higher levels of educa- tion are less likely to believe that the WB “operates in the best interest of society”. On the other hand, people who are religious and have a strong sense of ethnic pride are more likely to trust the WB to operate in ways that benefit society. The respondents who are “worried about globalization” tend to place greater trust in the WB, as well and those who live in a country with a higher per capita GDP feel the same way in terms of trusting this global financial institution. Moving onto Model 2, which incorporates one of the independent variables (GEN_TRUST), it is found that generalized trust is positively and significantly related to institutional trust, which conforms to previous re- search findings on social capital and political trust, as discussed above. Model 3 replaces the generalized trust variable with the one that measures transnational identity. Here the result is also significant, but the causation is in the opposition direction. While holding constant individual and country-level control variables, those who identify themselves as being “Asian” are found to be less likely to place their trust in the WB as a bene- ficial institution. The last model (Model 4) containing both independent variables lends further empirical support. Table 4 contains regression results based on the World Trade Organization as the dependent variable. Model 1, as before, is the baseline model, which consists of many control variables that reach the level of significance. Older subjects and those with higher educational attainment are more likely to distrust the WTO. Men and those who are married are also more likely to hold this view. In contrast, people who belong to a higher socioeconomic status (according to subjective assessment) have the opposite opinion. As for the religious category, Muslims are less likely to put their faith in the WTO as a benevolent organi- zation. Ethnic pride is positively associated with institutional trust. Per capita GDP is negatively related to it. And the coeffi- ient for the regional dummy variable suggests that those who c Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 277  H. H. KIM Table 4. Logistic coefficients from regressing TRUST_WTO on selected independent and control variables. Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Estimate S.E. Estimate S.E. Estimate S.E. Estimate S.E. AGE −.007** .003 −.008** .003 −.008** .003 −.008** .003 MALE −.121* .048 −.113* .048 −.123* .049 −.117* .049 MARRIED −.135* .059 −.148* .059 −.146* .060 −.160** .060 EDUC −.058** .018 −.052** .018 .066*** .018 −.060** .018 SES .079* .036 .072* .036 .073* .037 .068 .037 CATHOLIC .036 .133 .057 .134 .086 .135 .106 .135 PROTESTANT −.167 .109 −.175 .110 −.156 .110 −.164 .111 MUSLIM −.146* .071 −.161* .071 −.133 .071 −.147* .071 RELIGIOSITY .025 .015 .021 .015 .026 .015 .022 .015 ETHNIC_PRIDE .146*** .035 .137*** .036 .154*** .037 .146*** .037 ENGLISH .002 .030 −.004 .030 −.006* .031 −.011 .031 INT_EXP .175 .094 .168 .094 .216 .096 .208* .097 GLOB_WORRY .082 .102 .068 .103 .065 .103 .054 .103 ECON_WORRY −.017 .022 −.017 .022 −.017 .023 −.018 .023 GDP_PER −.213*** .018 −.215*** .021 −.218*** .022 −.214*** .024 EAST_ASIA .166* .079 .122 .081 .081 .082 .043 .084 GEN_TRUST .243*** .051 .228*** .052 TRANS_ID −.197*** .052 −.193*** .053 INTERCEPT1 −2.837*** −2.839*** −2.957*** −2.951*** INTERCEPT2 −.799*** −.798*** −.998*** −.986*** INTERCEPT3 1.774*** 1.789*** 1.592*** 1.607*** −2 LL 14375.080 14619.580 13816.777 13645.011 N 6461 6391 6207 6178 Note: *<.05; **<.01; ***<.001. live in East Asia (China, Japan, South Korea) are more likely to trust the WTO to operate in the best interest of their respective society. According to Model 2, generalized trust is again sig- nificantly and positively related to institutional trust. Consistent with the earlier finding, Model 3 in Table 4 offers the same result: transnational identity is negatively related to institutional trust. The regression coefficients from Model 4 point in the same consistent direction as well: those who are more likely to trust others have a greater tendency to trust an international organization to act in beneficial ways. On the other hand, the subjects who view themselves as belonging to a transnational group are less inclined to uphold this view. The last set of results from estimating logistic regression models, using institutional trust in MNCs as the dependent variable, are reported in Table 5. A similar set of individual attributes are found to be related to the outcome variable: age, gender, marital status, and educational attainment all negatively contribute to the level of institutional trust. Catholics and Mus- lims, however, have a more positive opinion of MNCs, as is the case with those who are more religious and take greater pride in their ethnic affiliation. The measure of national economic de- velopment, as reflected in the per capita GDP variable, is nega- tively associated with individual-level trust in global institu- tions. And people who live in East Asia are more likely to place their trust in MNCs to operate in the best interests of their re- spective society. The findings for the two main independent variables in Table 5 are basically identical compared with those from the previous analyses: while interpersonal generalized trust has a positive effect on people’s institutional trust, the latter is negatively associated with transnational identity. Discussion and Conclusion The intended purpose of this paper was to investigate the de- terminants of institutional trust. In particular, the empirical analysis was informed by two lines of inquiry-how generalized trust and transnational identity reely affect the degree of spectiv Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 278  H. H. KIM Table 5. Logistic coefficients from regressing TRUST_MNC on selected independent and control variables. Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Estimate S.E. Estimate S.E. Estimate S.E. Estimate S.E. AGE −.007** .002 −.007** .002 −.007** .002 −.007** .002 MALE −.099* .046 −.087 .046 −.111* .047 −.101* .047 MARRIED −.199*** .056 −.215*** .056 −.214*** .057 −.231*** .057 EDUC −.066*** .017 −.060** .017 −.067*** .018 −.061** .018 SES .065 .034 .053 .034 .057 .035 .045 .035 CATHOLIC .281* .129 .294* .130 .347** .130 .360** .131 PROTESTANT .003 .105 −.007 .107 .011 .106 .002 .107 MUSLIM .771*** .068 .760*** .069 .794*** .069 .785*** .069 RELIGIOSITY .039** .014 .035* .014 .034* .015 .029* .015 ETHNIC_PRIDE .080* .034 .058 .034 .101** .035 .079* .035 ENGLISH .045 .029 .046 .029 .025 .029 .025 .030 INT_EXP .080 .090 .074 .091 .137 .092 .130 .093 GLOB_WORRY .176 .100 .177 .101 .161 .101 .165 .102 ECON_WORRY .021 .021 .023 .021 .019 .022 .021 .022 GDP_PER −.121*** .017 −.123*** .015 −.119*** .012 −.117*** .015 EAST_ASIA .403*** .076 .355*** .078 .261** .080 .217** .081 GEN_TRUST .218*** .049 .214*** .050 TRANS_ID −.380*** .050 −.382*** .051 INTERCEPT1 −2.827*** −2.841*** −2.980*** −2.991*** INTERCEPT2 −.883*** −.900*** −1.158*** −1.173*** INTERCEPT3 1.528*** 1.517*** 1.272*** 1.264*** −2 LL 14745.766 14580.142 14265.751 14093.476 N 6527 6456 6300 6210 Note: *<.05; **<.01; ***<.001. individual confidence in the workings of global institutions, namely the World Bank, the WTO, and multinational corpora- tions. Quantitative results strongly support the claim that gen- eralized trust in fact leads to higher levels of institutional trust. There has been much theorizing about and looking into how and to what extent generalized or social trust shapes individual perception and evaluation of governmental, non-governmental, and for-profit organizations. The role of trust has been viewed as critical since it allows and facilitates many forms of social exchange (Cook, 2001; Gambetta, 1998). According to Fuku- yama (1995), it can even help explain the cross-national varia- tion in creating material prosperity (see also Knack & Keefer, 2007). Whether it relates to solving the Hobbesian problem of order (Gellner, 1998), reduce social complexities (Luhmann, 1980), or minimize the principal agent problem (Ensminger, 2001; Grief, 1989), trust has been shown to be of fundamental importance. It is also invaluable since it provides the lubricant necessary for the smooth functioning of political institutions. That is, the propensity to trust others can aid effective democ- ratic governance. It is with respect to this particular view that the role (i.e., political function) of trust has been developed into the social capital argument, as initially laid out by Putnam (1993, 2000). As one author puts it succinctly, “trust is proba- bly the main component of social capital, and social capital is a necessary condition of social integration, economic efficiency and democratic stability” (Newton, 2001: p. 202). This study offers further empirical light on the causal rela- tionship between social capital and institutional trust but does so by extending the analysis to go beyond treating local politi- cal organizations as the main outcome variables, which has been the case with the bulk of the previous research. The quan- titative results reported above adds a global dimension to the inquiry by analyzing individual-level institutional trust of three major organizational actors that embody economic globaliza- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 279  H. H. KIM tion. In addition, the causal impact of a new independent vari- able is examined, something that the extant literature does not take into account. In the era of increasing economic and cul- tural globalization, transnational identity has become one of the characteristic traits of contemporary life. How people perceive themselves has critical ramifications in terms of policy choices and preferences. As Kunovich (2009) shows, for example, there is a strong association between the content of national identity and the types of domestic and foreign policies people prefer and endorse, which can “affect both potential members of a nation and a nation’s interactions with other countries” (591). One of the contributions this paper makes is to examine the extent to which people’s self-identification affects their subjec- tive evaluation of a global financial institution, an international regulatory agency, and multinational businesses. According to the regression output, the coefficients for the transnational identity variable are consistently robust and negative: those who identify themselves as belonging to a group that lies be- yond national borders are less likely to trust global institutions to function in ways that could benefit their lives. This is a novel finding with interesting implications. Clearly, globalization will only intensify over time. As many scholars have observed, the multifaceted process of globalization “is here to stay.” And “how it will be governed is the [only] question” (Nye & Dona- hue, 2000: p. 38). Naturally, then, globalization will usher in ever more forcefully transnational identities. After all, their rise is seen as an inevitable product of cultural globalization, as Huntington’s (1993, 1996) clash of civilization argument and related others have made all too apparent. If so, there will be a growing tension between the increasing and perhaps inexorable roles played by international organizations like the WB, the WTO and MNCs as agents of globalization and people’s dis- trust in them as they progressively take on an identity that tran- scends national boundaries. It remains an empirical question as to how and to what degree this tension will get in the way of effective global governance, an issue that remains both urgent and controversial (Brown et al., 2000). The current study has some limitations, which point toward the possible directions for future research. First of all, as Hardin (2002) explains, much of the research on social capital and institutional or political trust is really about the “trustworthi- ness” of political institutions. As such, researchers should in- clude in the analysis various performance-related satisfaction measures. This would provide a more conservative and hence more accurate test of whether or not generalized trust has any causal influence on institutional trust. The dataset provided by the Asian Barometer Survey, unfortunately, does not provide information on institutional performance. Also problematic may be the questionnaire designed to measure generalized trust. As Hardin (2002) points out, what the standard survey question seeks to measure “is not genuinely generalized trust. The re- spondents are forced by the vagueness of the questions to give vague answers, and it is a misdescription to label their re- sponses as generalized trust” (61). This study tried to overcome this limitation by creating the generalized trust variable using another question in the survey (“Do you think that people gen- erally try to be helpful or do you think that they mostly look out for themselves?”). This too, however, is not without conceptual and methodological problems, and future research should come up with a variety of improved questions as possible alterna- tives. Another shortcoming has to do with the issue of causality. Though this is not a major concern for the present study, it is something that plagues many others that seek to establish a link between social capital and various outcome variables related to democracy and democratic governance. According to Paxton’s (2002) findings, the relationship between social capital, which she conceptualizes in terms of generalized trust and associa- tional membership, and democracy is reciprocal. Using panel data, she demonstrates that the causality in fact runs both ways. Studies based on longitudinal data would minimize this thorny issue and help produce more convincing results underscoring the role of social capital in producing institutional trust, support for democracy, and political activism as well as other important outcomes. Also, there may be critical contextual factors, such as the level of democratic development of a nation, that mediate the effects of generalized trust on various political conse- quences, which many previous studies have ignored (see Jamal & Noorudin, 2010). Future attempts need to incorporate these into the analytical framework for more nuanced arguments concerning the “functions” of social capital. The literature on generalized trust and social capital is indeed huge and growing. They have given much legitimacy to the political culture perspective and offered valuable insights into the workings of various aspects of democracy. As is the case with any other popular concept in the social sciences, however, they suffer from the danger of losing heuristic value. Preventing that from happening will require more careful hypothesizing about the causality between independent and dependent vari- ables and a more refined methodological approach geared to- ward collecting higher quality data. This is a tall order but one that promises a great deal of intellectual payoff. REFERENCES Appadurai, A. (2000). Disjuncture and difference in the global cultural economy. In F. J. Lechner, & J. Boli (Eds.), The globalization reader (pp. 322-330). Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. Applebaum, A. I. (2000). Culture, identity, and legitimacy. In J. S. Nye, & J. D. Donahue (Eds.), Governance in a globalizing world (pp. 319-329). Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press. Arts, W., & Halman, L. (2006). National identity in Europe today. International Journal of Sociology, 35, 69-93. doi:10.2753/IJS0020-7659350404 Berger, P. L., & Huntington, S. P. (Eds.) (2002). Many globalizations: Cultural diversity in the contemporary world. New York: Oxford University Press. Braithwaite, V., & Levi, M. (Eds.) (2002). Trust and governance. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Brehm, J., & Rahn, W. (1997). Individual-level evidence for causes and consequences of social capital. American Journal of Po litical Science, 41, 999-1023. doi:10.2307/2111684 Brown, D., Khagram, S., Moore, M., & Frumkin, P. (2000). Globaliza- tion, NGOs, and multisectoral relations. In J. S. Nye, & J. D. Dona- hue (Eds.), Governance in a globalizing world (pp. 271-296). Wash- ington DC: Brookings Institution Press. Cook, K. S. (Ed.) (2001). Trust in society. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Dekker, P., & Uslaner, E. (Eds.) (2001). Social capital and participa- tion in everyday life. London: Routledge. Delhey, J., & Newton, K. (2003). Who trusts: The origins of social trust in seven societies. European Societies, 5, 93-137. doi:10.1080/1461669032000072256 Denters, B., Gabriel, O., & Torcal, M. (2007). Political confidence in representative democracies. In J. Van Deth, J. R. Montero, & A. Westholm (Eds.), Citizenship and involvement in European democ- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 280  H. H. KIM Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 281 racies. A comparative analysis. London: Routledge. Edlund, J. (2006). Trust in the capability of the Welfare State and gen- eral Welfare State support: Sweden 1997-2002. Acta Sociologica, 49, 395-417. doi:10.1177/0001699306071681 Ensminger, J. (2001). Reputation, trust, and the principal agent problem. In K. S. Cook (Ed.), Trust in society. New York: Russell Sage Foun- dation. Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The social virtues and creation of pros- perity. New York: Basic Books. Gambetta, D. (Ed.) (1988). Trust: Making and breaking cooperative relations. Oxford: Blackwell. Gellner, E. (1988). Trust, cohesion, and the social order. In D. Gam- betta (Ed.), Trust: Making and breaking cooperative relations (pp. 142-157). Oxford: Blackwell. Greif, A. (1989). Reputation and coalitions in the medieval trade: Evi- dence on the Maghribi traders. Journal of Economic History, 49, 857-882. doi:10.1017/S0022050700009475 Hardin, R. (2002). Trust and trustworthiness. New York: Russell Sage. Hsiao, H. M. (2002). Cultural globalization and localization in con- temporary Taiwan. In P. Berger, & S. Huntington (Eds.), Many glob- alizations: Cultural diversity in the contemporary world (pp. 48-67). New York: Oxford University Press. Huntington, S. (1993). The clash of civilizations. Foreign Affairs, 72, 22-49. doi:10.2307/20045621 Huntington, S. (1996). The clash of civilizations and the remaking of world order. New York: Simon and Schuster. Inglehart, R. (1997). Modernization and postmodernization: Cultural, economic, and political changes in 43 societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Inglehart, R., & Welzel, C. (2005). Modernization, cultural change, and democracy: The human development sequence. New York: Cambridge University Press. Jamal, A., & Nooruddin, I. (2010). The democratic utility of trust: A cross-national analysis. Journal of Po litics, 71, 45-59. doi:10.1017/S0022381609990466 Johnson, I. (2005). Political trust in societies under transformation: A comparative analysis of Poland and Ukraine. International Journal of Sociology, 35, 63-84. Keele, L. (2007). Social capital and dynamics of trust in government. American Journal of P olitical Science, 51, 241-254. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00248.x Kim, J. Y. (2005). Bowling together isn’t a cure-all: The relationship between social capital and political trust in South Korea. Interna- tional Political Science Review, 26, 193-213. doi:10.1177/0192512105050381 Knack, J., & Keefer, P. (2007). Does inequality harm growth only in democracies: A replication and extension. American Journal of Po- litical Science, 41, 323-332. doi:10.2307/2111719 Kunovich, R. M. (2009). The sources and consequences of national identification. American Sociologica l Review, 74, 573-593. doi:10.1177/000312240907400404 Lechner, F. J., & Boli, J. (Eds.) (2000). The globalization reader. Ox- ford: Blackwell. Letki, N. (2006). Investigating the roots of civic morality: Trust, social capital, and institutional performance. Political Behavior, 28, 305- 325. doi:10.1007/s11109-006-9013-6 Luhmann, N. (1980). Trust and power. New York: Wiley. Mishler, W., & Rose, R. (2005). What are the political consequences of trust? A test of cultural and institutional theories in Russia. Com- parative Political Studies, 38, 1050-1078. doi:10.1177/0010414005278419 Newton, K. (2001). Trust, social capital, civil society, and democracy. International Political Sci e nc e Review, 22, 201-214. doi:10.1177/0192512101222004 Newton, K., & Norris, P. (2000). Confidence in public institutions: Faith, culture, or performance? In S. Pharr, & R. Putnam (Eds.), Dis- affected democracies: What’s troubling the trilateral countries? Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Nooteboom, B. (2007). Social capital, institutions, and trust. Review of Social Economy, 65, 29-53. doi:10.1080/00346760601132154 Norris, P. (2000). Global governance and cosmopolitan citizens. In J. S. Nye, & J. D. Donahue (Eds.), Governance in a globalizing world (pp. 155-177). Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press. Nye, J. S., & Donahue, J. D. (Eds.) (2000). Governance in a globalizing world. Washington DC: Brookings. Paxton, P. (2002). Social capital and democracy: An interdependent relationship. Am e ri ca n So ci ological Review, 67, 254-277. doi:10.2307/3088895 Putnam, R. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in mod- ern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of Ameri- can community. New York: Simon and Schuster. Rahn, W. M., & Rudolph, T. J. (2005). A tale of political trust in American cities. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 69, 530-560. doi:10.1093/poq/nfi056 Rosendorf, N. M. (2000). Social and cultural globalization: Concepts, history, and America’s role. In J. S. Nye, & J. D. Donahue (Eds.), Governance in a globalizing world (pp. 109-134). Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press. Rothstein, B. (2002). Social capital in the social democratic state. In R. Putnam (Ed.), Democracies in flux. The evolution of social capital in contemporary societ y. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Rothstein, B., & Uslaner, E. (2005). All for all: Equality, corruption, and social trust. World Pol itics, 58, 41-72. doi:10.1353/wp.2006.0022 Sassen, S. (1998). Globalization and its discontents. New York: The New Press. Seligman, A. (1997). The problem of trust. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Smith, D. A., Solinger, D. J., & Topik, S. T. (Eds.) (1999). States and sovereignty in the global economy. London: Routledge. Srinivas, T. (2002). The Indian case of cultural globalization. In P. Berger, & S. Huntington (Eds.), Many globalizations: Cultural di- versity in the contemporary world (pp. 89-116). New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/0195151461.003.0005 Sum, N. L. (2000). Globalization and its other(s): Three ‘new kinds of orientalism’ and the political economy of trans-border identity. In C. Hay, & D. Marsh, (Eds.), Demystifying globalization. New York: St. Martin’s Press. Sztompka, P. (1999). Trust: A sociological theory. Cambridge: Cam- bridge University Press. Uslaner, E. (2002). The moral foundations of trust. New York: Cam- bridge University Press. Zmerli, S., & Newton, K. (2008). Social trust and attitudes toward democracy. Public Opinion Quarterly, 72, 706-724. doi:10.1093/poq/nfn054

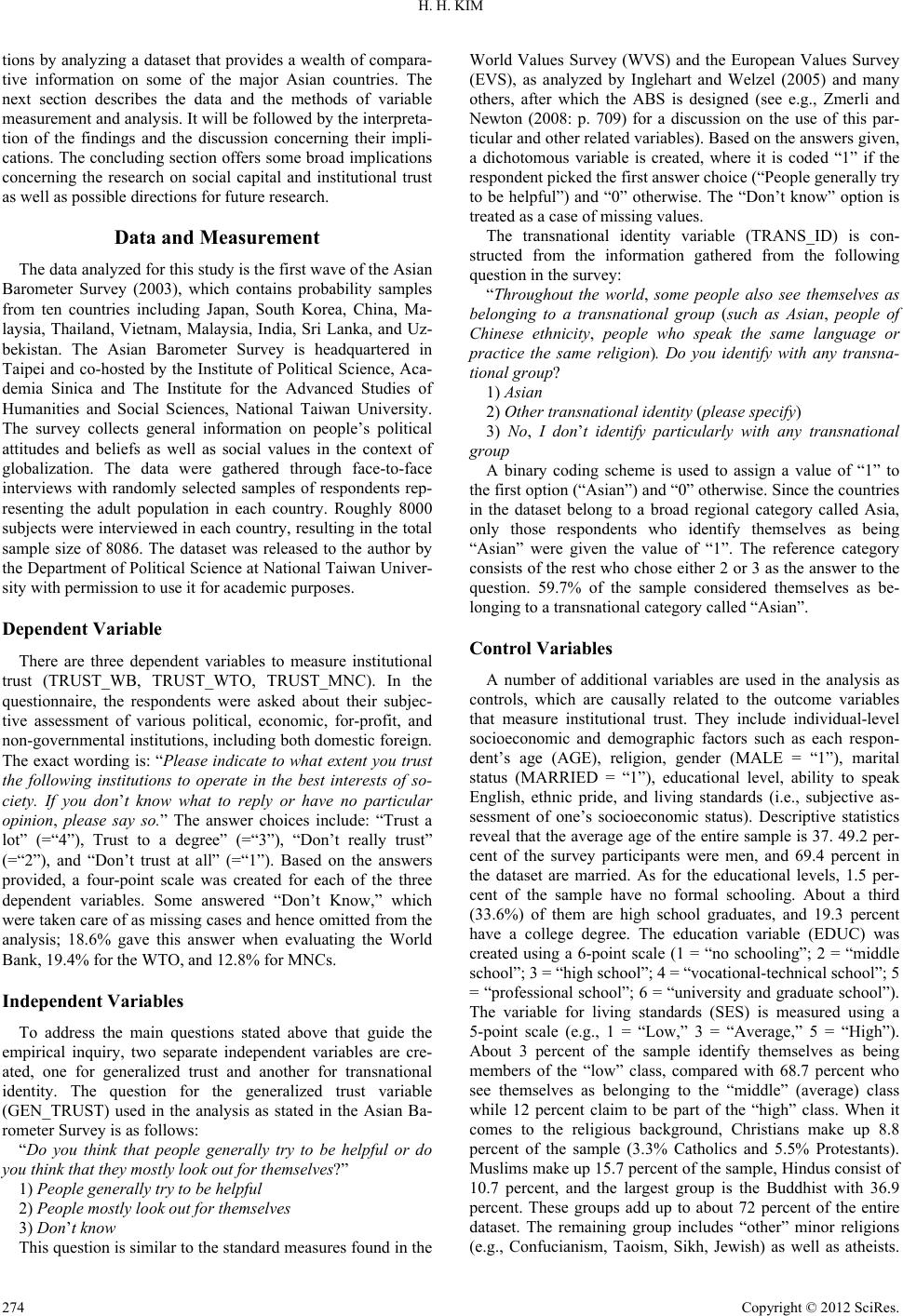

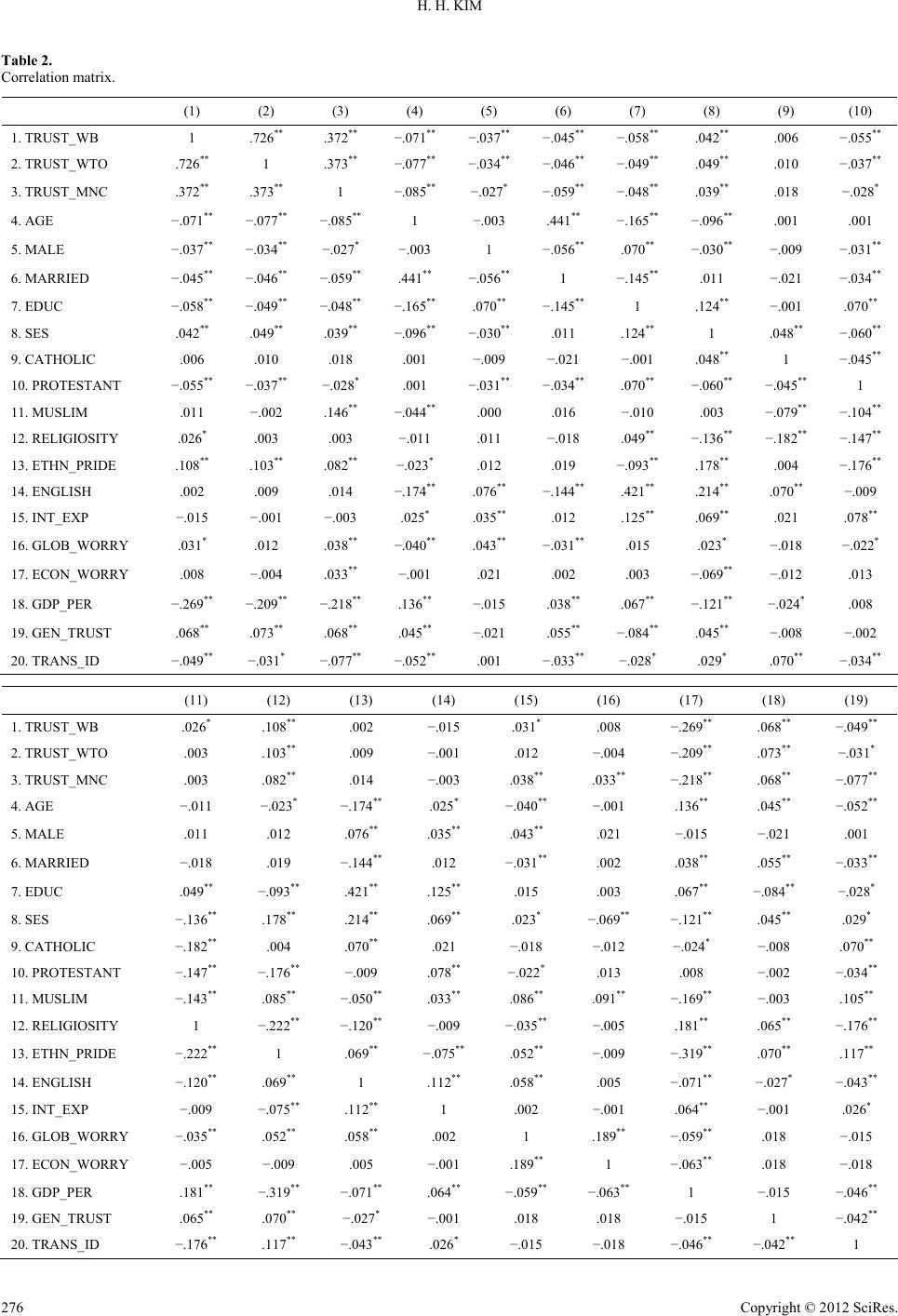

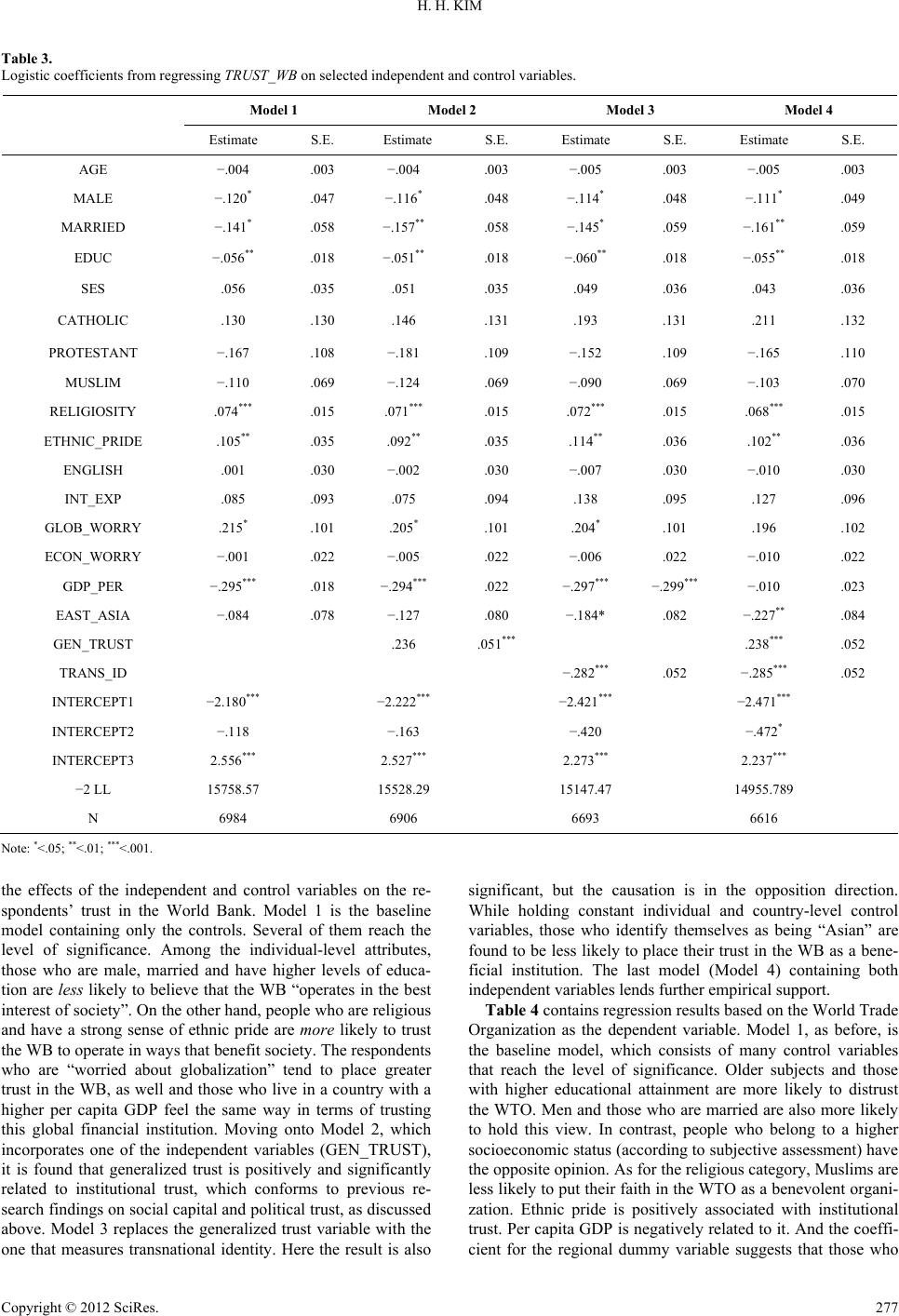

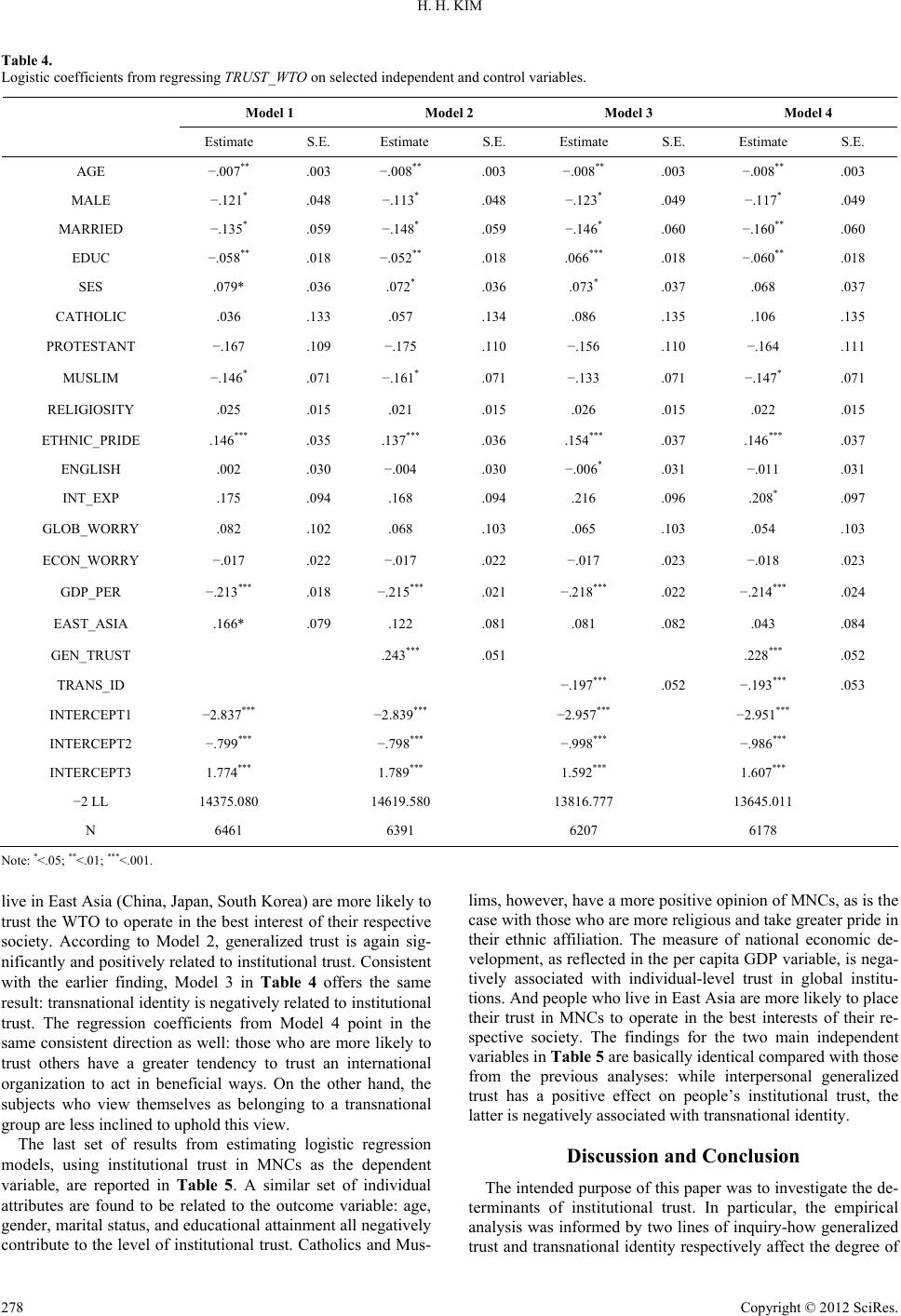

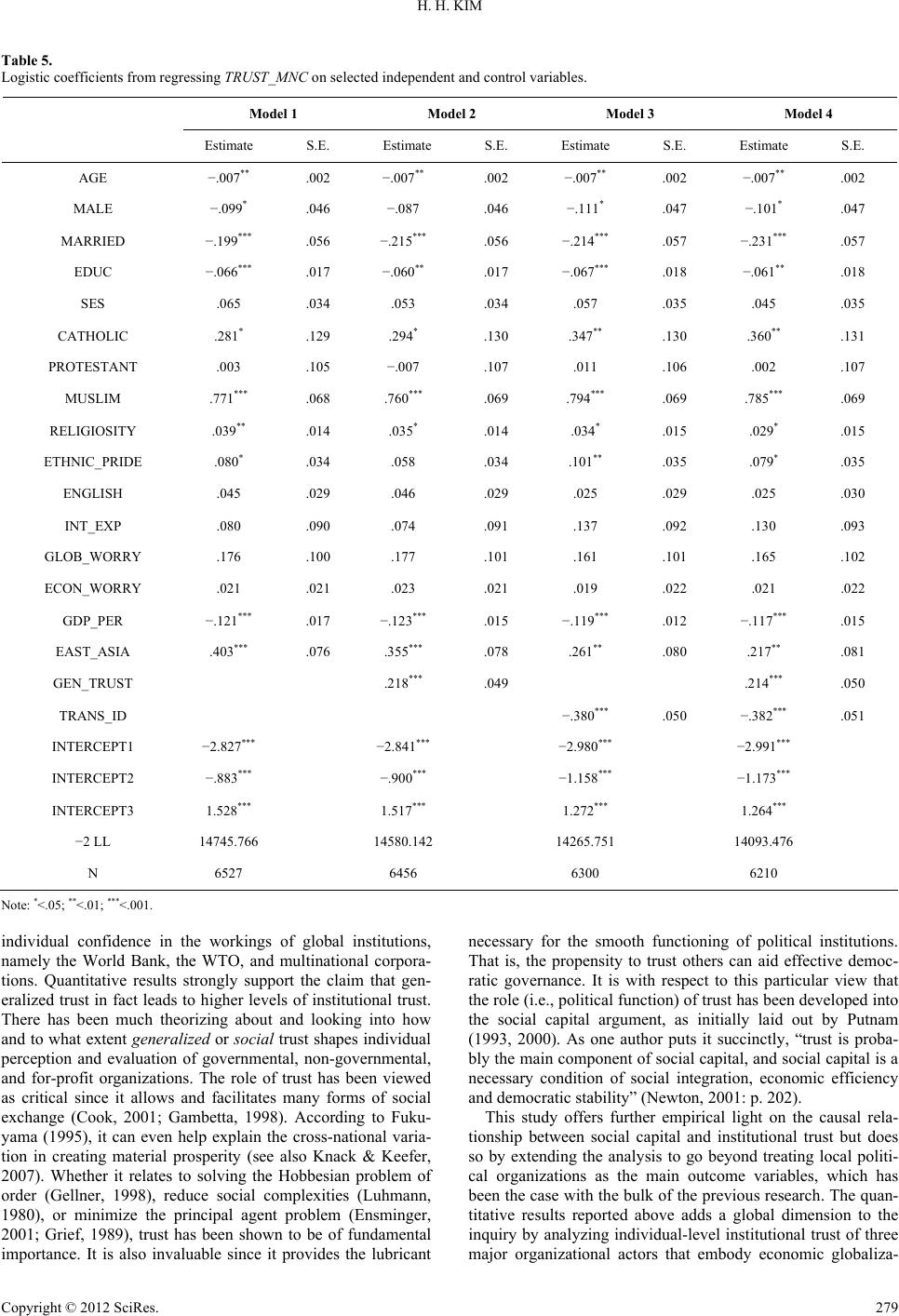

|