Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

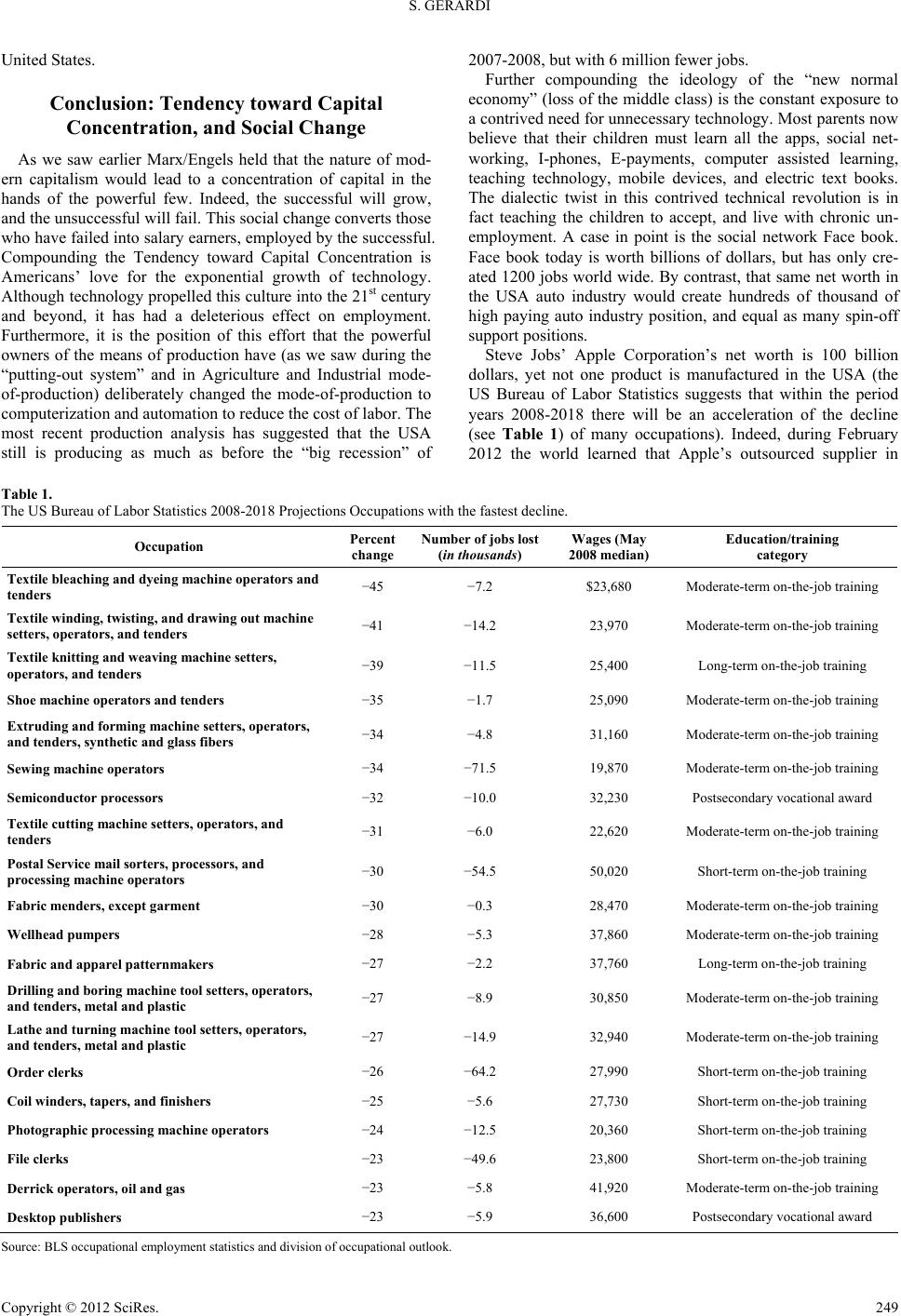

Sociology Mind 2012. Vol.2, No.3, 247-250 Published Online July 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/sm) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/sm.2012.23032 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 247 Social Change, Historical Modes-of-Production and the Tendency toward Capital Concentration Steven Gerardi New York City College of Technology, New York, USA Email: SGerardi@Citytech.Cuny.Edu Received March 5th, 2012; revised April 8th, 2012; accepted May 10th, 2012 This effort suggests that a key component within the conflict paradigm often not referred to in the litera- ture is the Tendency toward Capital Concentration as a function of historical changing economic modes- of-production. Furthermore, modes-of-production change is the primary force of social change within the conflict view. This effort will cite several examples of changing economic modes-of-production as the result of Tendency toward Capital Concentration, which has acted as force of social change. Keywords: Socail Change; Mode-of-Productions; Capitial Concentration Introduction Marx/Engels’ concept of “Historical Materialism” incorpo- rates in a capsule the idea that history is not merely an accumu- lation of accidents or deed of great men as many historians argue, but the development of the human race through its’ labor and productive force or “species-being”. Consistent with the philosophy of Historical Materialism, Marx/Engels developed an important concept concerning modern society—that of Ali- enation or Estrangement of Labor. Alienation, for Marx/Engels, was seen as humanity not experience itself as the acting agent in an attempt to own the objects of labor. Essentially, objects of the individuals’ creation stand above and against them. Hence, alienation is experiencing the world and oneself passively, as the individual separated from the object he/she has created. Marx/Engels also argued that labor under capitalism appears only as a means of sustaining life and not a creative activity, thus a contradiction of nature (species being). The concept of Alienated Labor is further supported by, and correlated to, the Theory of Surplus Value. Marx was an economist, and often defined economic concepts through mathematical expressions. The Theory of Surplus Value is therefore expressed as an equa- tion—the total value of the end product over the sum of it’s’ parts. This equation suggests that the end product is always more valuable then the sum of its parts, which includes human labor. The net result, as the value of “things” increases, the value of humanity decreases (because human labor is only seen as a piece of the overall production process). Moreover, Marx/ Engels argued that there can not be a separation from the con- tinuous transformation of nature’s raw material into human form, and the material human conciseness. This concept Marx/Engels labeled the “mode-of-production”. In the German Ideology, Marx/Engels defined the Mode-of- Production as “everything that goes into the production of the necessities of life, including the productive forces” (labor, in- struments, and raw material) and the... “Relations of produc- tion” (the social structures that regulate the relation between humans in the production of goods “…Furthermore, for indi- viduals, the mode of production is...”1 a definite form of ex- pressing their life, a definite mode of life on their part. As indi- viduals express their life, so they are. What they are, therefore, coincides with their production, both with what they produce and how they view themselves. Therefore, when there is a change in the Mode-of-Production, there is a direct change in the means of production, human relationships, and thus social change. This effort strongly suggests that historical mode-of- production change is brought on by the powerful few in the Tendency Toward Capital Concentration. Historical Changing Modes-of-Production, the Tendency toward Capital Concentration, and Social Change Marx/Engels held that the nature of modern capitalism would lead to a concentration of capital in the hands of the powerful few through economic competition. The successful will grow and the unsuccessful will fail. According to this concept those who have failed ultimately find themselves employed as salary earners of the successful. Indeed, one salient case in point is the “Putting-out system” of the 1830’s. It has been hypothesized that most urban centers begin as commercial cities in which there is the exchange of agricultural commodities grown in the hinterlands. The buying and selling of crops by the merchant capitalist class developed large finance centers in the modern cities. This investment class generated large profits which were reinvested into the “put- ting-out-system”. Over a short period of time the investment class took control of the distribution of raw materials the Cot- tage handicraft industries (the mode-of-production of the time in many cities during the late 1830s) needed to produce their product. This investment class over time took control of the collection and sail of the products produced in the Cottage Handicraft Industries (eliminating or “putting-out” of business the Cottage Handicraft owners). Hence, during the turn of the 19th century the “putting-out system” converted the handicraft mode-of-production to industrialization. This conversion con- centrated the handicraft owners (now wage workers of the suc- cessful) in a central production area known as the factory. In- 1The German Ideology Part One, pg 221, New York: International Publish- ers , 2001.  S. GERARDI deed, the factory acts as the nucleus of the city (zone one where the workers of the factory resided). This change in the mode- of-production underscored changes in occupational structure and patterns of residential areas. Again changing the mode-of- production as a Tendency Toward Capital Concentration pro- duces a “definite form of expressing their life, a definite mode of life on their part. As individuals express their life, so they are. What they are, therefore, coincides with their production, both with what they produce and how they produce” (Ibid, 221). Mode-of-Production and Social Relationships Today on many world continents females are reduced to ob- jects. Females’ noses and ears are cut off if they disobey their in-laws. Young girls who wish to attend school have battery acid thrown into their faces, and the female teachers are be-headed. Females cannot drive a car, or even go outside without a male escort. Female rape victims are given a harsher sentence than their attackers. Mothers’ are hung because they give birth to only females. Oldest females (in an all female child household) are forced to cross dress for it is seen as “good luck” for the next child to be a male. Others are stoned to death if they are convicted of adultery. In still another continent when parents learn that their child will be female (as determined by amniocentesis), the fetus is aborted. More horrifying, female infants are literately thrown into the streets as if garbage. Wife burning is looked upon with a blind eye by the State Authorities (when it is believed that the bride’s father “lied” about her dowry), and female honor killings is still seen as a male duty. The erroneous belief is that such objectification is based upon religious beliefs. But in most cases these populations have different religions. Hence, it cannot be religion. Another erro- neous belief is that it is cultural. However, these societies clearly do not have the same culture. Indeed, what all these nations have in common is their economy mode-of-production. They are either in an agricultural mode-of-production, or are transitioning from agricultural to industrialization mode-of- production. This effort suggests that located in Fredrick Engels’ work entitled The Origins of the Family, Private Property and the State the answer to these troubling questions are explained from an objective sociological analysis. In this work Engels traces gender roles through the stages of historical economic development or modes-of-production. He further developed the concept known as the Resources Power Theory. This theory suggests that whoever has the most resources in a relationship has the most power (these resources may be money, gold, land, or domesticated animals, in short, private property). Thus, ac- cording to Engels when there is a historical change in the mode-of-production, there is a direct change in the power which each gender may enjoy within a given mode-of-produc- tion. As we saw earlier, this effort suggests that the powerful are always manipulating the economy on their behalf. In the case of historical gender roles, Engels identified four stages of historical economic modes-of-production and suggested that when there is a mode-of-production change there is a direct change in the Resource Power Theory, changing the status of males and females in society. The four modes-of-productions Engels identified are Savagery (Hunting and Gathering), Bar- barism (Agricultural), Civilization (Industrial), and the fourth is referred to as Post-Modern. The first historical mode-of-production is “Savagery”, or Hunters and Gathers. Engels suggested that during this stage property was communal, and characterized by females holding high status. Engels further suggested that women held high status because they contributed equally to the survival of the group by providing gathered foods such as fruits, roots and nuts. Therefore, when males did not return with meat from hunting, the group lived on. No one held the Resource Power Theory, therefore both males and females were considered equal. Fur- thermore, Hunters and Gathers were nomadic, and according to Engels have no notion of private property. This was a signifi- cant factor in gender relationships for there was no concept of “my woman” as private property. Having no notion of private property further contributed to the high status of woman within this stage of development. The second mode-of-production is “Barbarism” or Agricul- tural. During this period humans learn to breed domestic ani- mals, practice agriculture, and understand methods of increas- ing the supply of food products. Although during this period private property becomes the social reality (the land needed to grow the crops), and humanity thrives, Engels argued that dur- ing this stage patriarchal domination occurs (because of the psychical labor required to cultivate the land, and domesticated animals). As a result, all private property including females and children become the private property of the males, and mo- nogamy becomes the prevailing social relationship. Further- more, private property, marriage and reproduction all become linked during this stage, creating patriarchal hegemony (the inheritance patterns around the world generally entitle the old- est male child to all the wealth, status, and power that the father has accumulated throughout his life). The logical extension of this social hierarchy of authority is male domination over all property and production. The third mode-of-production is (Civilization) Industrializa- tion. Within this period humanity masters advanced mechanical forms of work. Although during the Industrial mode-of-pro- duction males and females are working side by side on the fac- tory floor, females are still considered inferior. Engels argued this is so because the Industrialization period is a continuation of the Agricultural period. Hence, there is no change in the male/female mindset during the Industrial stage. Therefore, societies that are still in the second Mode-of- Production, (Barbarism) Agricultural, and/or are transitioning from Agricultural Mode-of-Production, to (Civilization) Indus- trialization, will based upon Engels’ hypothesis objectify woman, and control of this mode-of-production. Engels suggested that there would be a workers’ revolution which would render male and female free and equal. This workers revolution would create the forth mode-of-production referred to as Post-Modern. Although in the United States there has not been a “workers revolution”, there has been a social revolution producing a movement to economic and social equality. During this period education is required because of the complexities of the work place. According to Engels, during the post-modern mode-of-production the Recourse Power Theory will level off, creating more equality for females. This predic- tion was insightful, although far from being equal today 36% of the females and 28% of the males earn Baccalaureate degrees. Of the total number of Maters Degrees earned, 60% go to fe- males. Females hold 56% of all professional careers. During today’s economic “great recession” women are doing better in this post-modern economy (8.3% unemployment) than men (9.3% unemployment). Therefore, the Post-Modern mode-of- production has had a profound effect on gender roles in the Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 248  S. GERARDI Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 249 United States. Conclusion: Tendency toward Capital Concentration, and Social Change As we saw earlier Marx/Engels held that the nature of mod- ern capitalism would lead to a concentration of capital in the hands of the powerful few. Indeed, the successful will grow, and the unsuccessful will fail. This social change converts those who have failed into salary earners, employed by the successful. Compounding the Tendency toward Capital Concentration is Americans’ love for the exponential growth of technology. Although technology propelled this culture into the 21st century and beyond, it has had a deleterious effect on employment. Furthermore, it is the position of this effort that the powerful owners of the means of production have (as we saw during the “putting-out system” and in Agriculture and Industrial mode- of-production) deliberately changed the mode-of-production to computerization and automation to reduce the cost of labor. The most recent production analysis has suggested that the USA still is producing as much as before the “big recession” of 2007-2008, but with 6 million fewer jobs. Further compounding the ideology of the “new normal economy” (loss of the middle class) is the constant exposure to a contrived need for unnecessary technology. Most parents now believe that their children must learn all the apps, social net- working, I-phones, E-payments, computer assisted learning, teaching technology, mobile devices, and electric text books. The dialectic twist in this contrived technical revolution is in fact teaching the children to accept, and live with chronic un- employment. A case in point is the social network Face book. Face book today is worth billions of dollars, but has only cre- ated 1200 jobs world wide. By contrast, that same net worth in the USA auto industry would create hundreds of thousand of high paying auto industry position, and equal as many spin-off support positions. Steve Jobs’ Apple Corporation’s net worth is 100 billion dollars, yet not one product is manufactured in the USA (the US Bureau of Labor Statistics suggests that within the period years 2008-2018 there will be an acceleration of the decline (see Table 1) of many occupations). Indeed, during February 2012 the world learned that Apple’s outsourced supplier in Table 1. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics 2008-2018 Projections Occupations with the fastest decline. Occupation Percent change Number of jobs lost (in thousands) Wages (May 2008 median) Education/training category Textile bleaching and dyeing machine operators and tenders −45 −7.2 $23,680 Moderate-term on-the-job training Textile winding, twisting, an d drawing out machine setters, operators, and tenders −41 −14.2 23,970 Moderate-term on-the-job training Textile knitting and weaving machine setters, operators, and tenders −39 −11.5 25,400 Long-term on-the-job training Shoe machine operators and tenders −35 −1.7 25,090 Moderate-term on-the-job training Extruding and forming machine setters, operators, and tender s , synthe tic and glass fibers −34 −4.8 31,160 Moderate-term on-the-job training Sewing machine operators −34 −71.5 19,870 Moderate-term on-the-job training Semicon ductor proc essors −32 −10.0 32,230 Postsecondary vocational award Textile cutting machine setters, operators, and tenders −31 −6.0 22,620 Moderate-term on-the-job training Postal Service mail sorters, processors, and processi ng mach i n e op erators −30 −54.5 50,020 Short-term on-the-job training Fabric menders, except garment −30 −0.3 28,470 Moderate-term on-the-job training Wellhead pumpers −28 −5.3 37,860 Moderate-term on-the-job training Fabric and apparel patternmakers −27 −2.2 37,760 Long-term on-the-job training Drilling and boring machine tool setters, operators, and tenders, metal and pla stic −27 −8.9 30,850 Moderate-term on-the-job training Lathe and turning machine tool setters, operators, and tenders, metal and pla stic −27 −14.9 32,940 Moderate-term on-the-job training Order clerks −26 −64.2 27,990 Short-term on-the-job training Coil winders, tapers, and finishers −25 −5.6 27,730 Short-term on-the-job training Photographic processing machine operators −24 −12.5 20,360 Short-term on-the-job training File clerk s −23 −49.6 23,800 Short-term on-the-job training Derrick operators, oil and gas −23 −5.8 41,920 Moderate-term on-the-job training Desktop publishers −23 −5.9 36,600 Postsecondary vocational award S ource: BLS occupational employment statistics and division of occupational outlook.  S. GERARDI China has been cited for forced labor practices (slavery). To sum-up, weather it is the “putting-out System, or male domination, or automation, the powerful are always manipulat- ing the economy to maximize their wealth and social position in the hierarchies of power and authority. Today we are only now seeing that the Tendency Toward Capital Concentration (through technical means) in post-modern society has untimely lead to the “objectification” of both man and woman alike. REFERENCES Aronowitz, S. (1992). The crisis in historical materialism. New York: J. F. Bergin Publishers Inc. Aronowitz, S. (1988). Science and power: Discourse and ideology in modern society. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. Bottomore, T. B. (1995). Alienated labor by Karl Marx: Early writings, 1963. Boston: McGraw-Hill Companies. Burke Leacock, E. (1972). Engels, Fredrick, the origin of the family. New York: Private Property and the State International Publishers. Feuer, L. (1995). Marx & Engels basic writings on politics and phi- losophy. New York: Doubleday and Company Garden City. Gerardi, S. (2011). A brief survey of the sociological imagination. Du- buque, IA: Kendall Hunt Publishing Co. Hutton, W. (1997). The state to come. London: Vintage Books. Martin, J. (1996). Marxism and totality. Berkeley: University of Cali- fornia Press. Marx, K. (2001). The German ideology. New York: International Pub- lishers. Wilson, J. (1996). When work disappears. New York: Random House Inc. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 250 |