Paper Menu >>

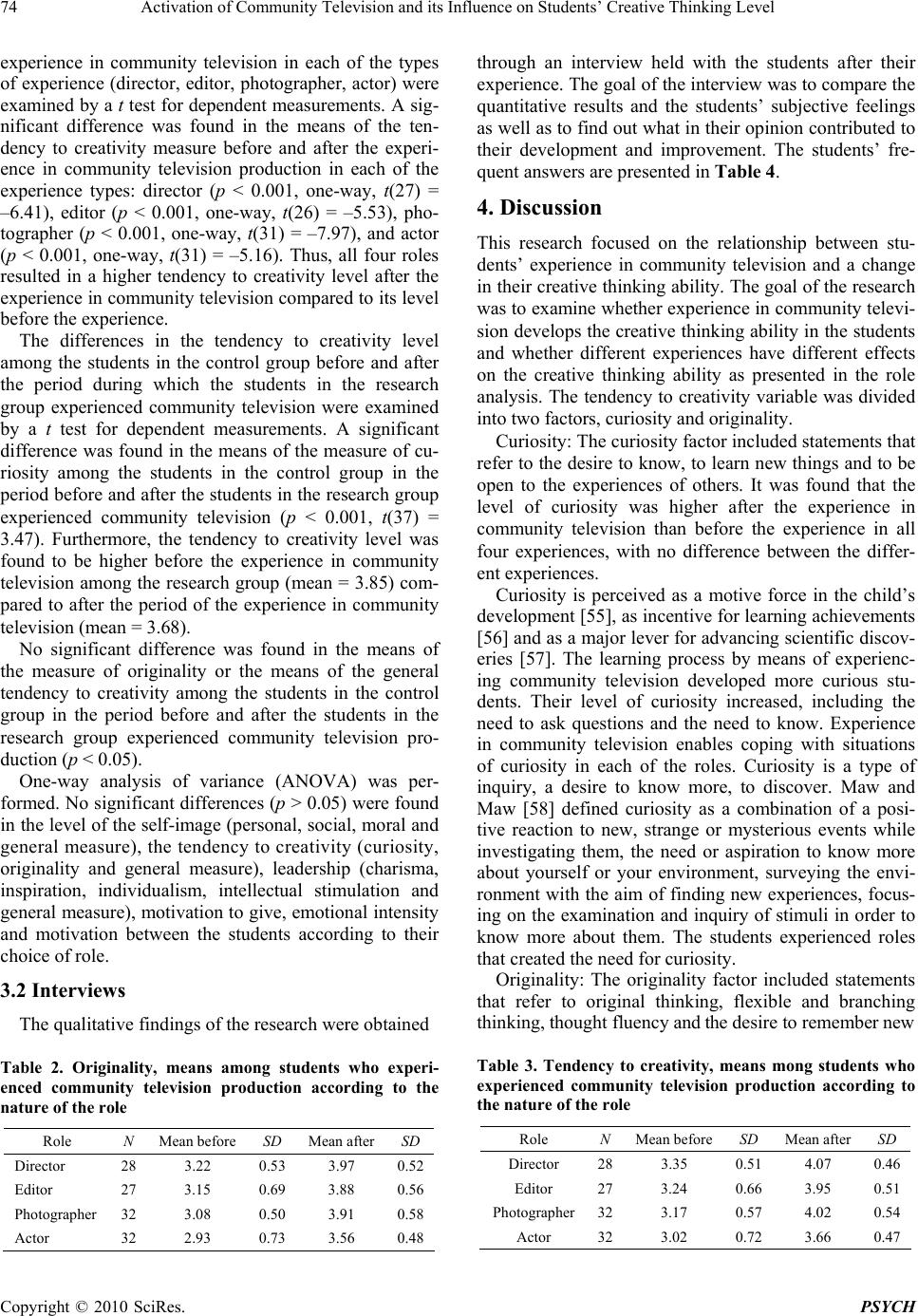

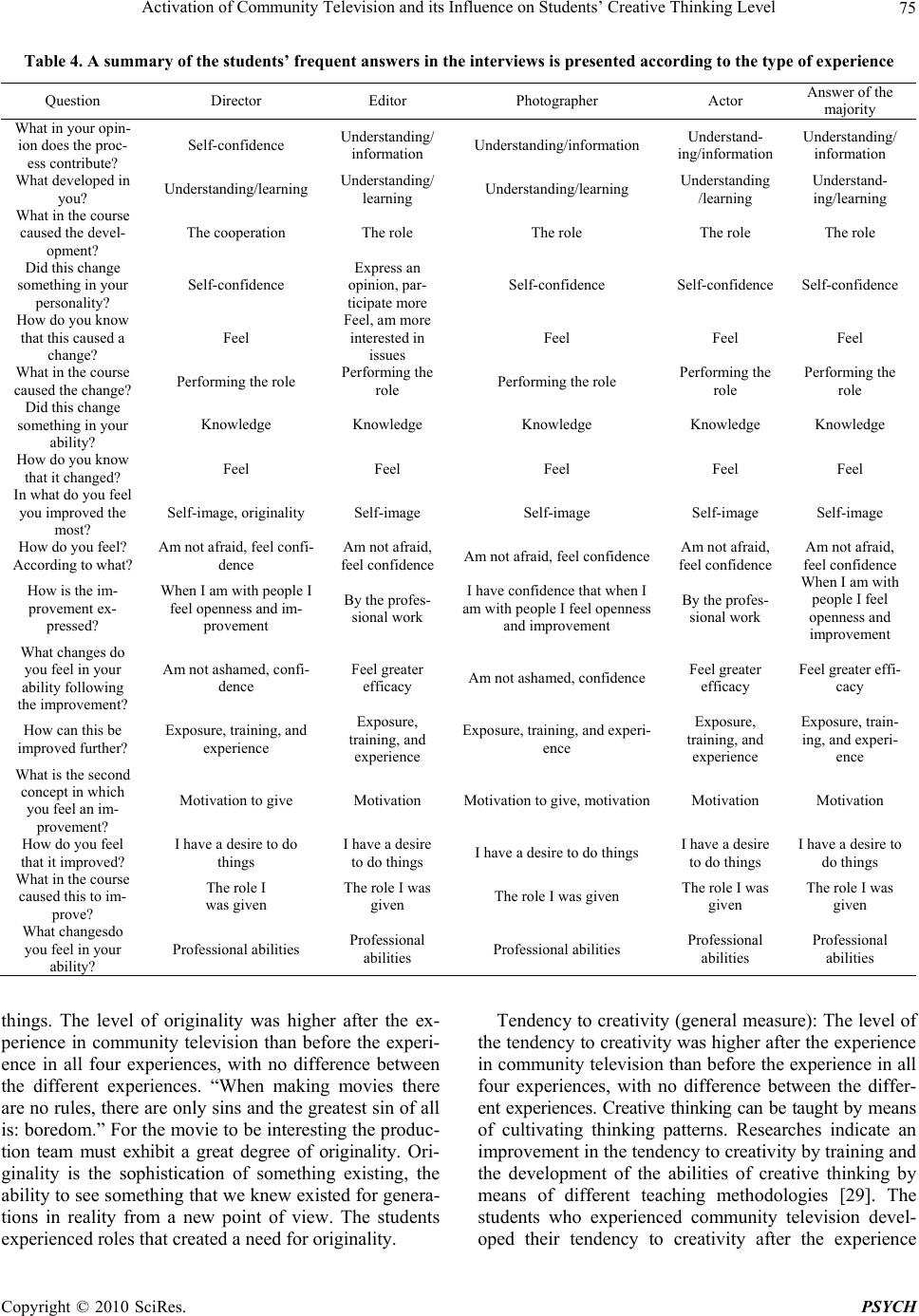

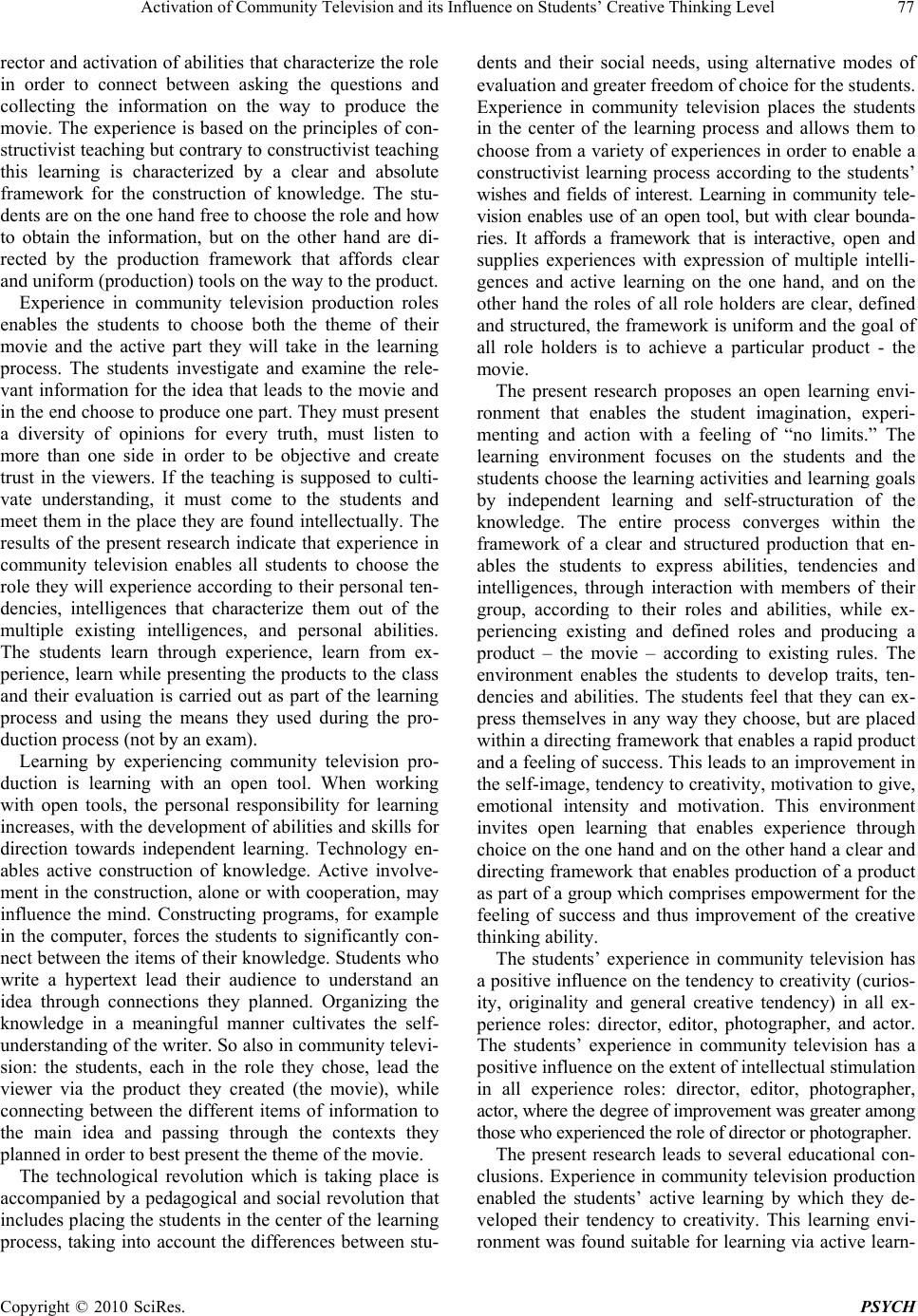

Journal Menu >>