Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

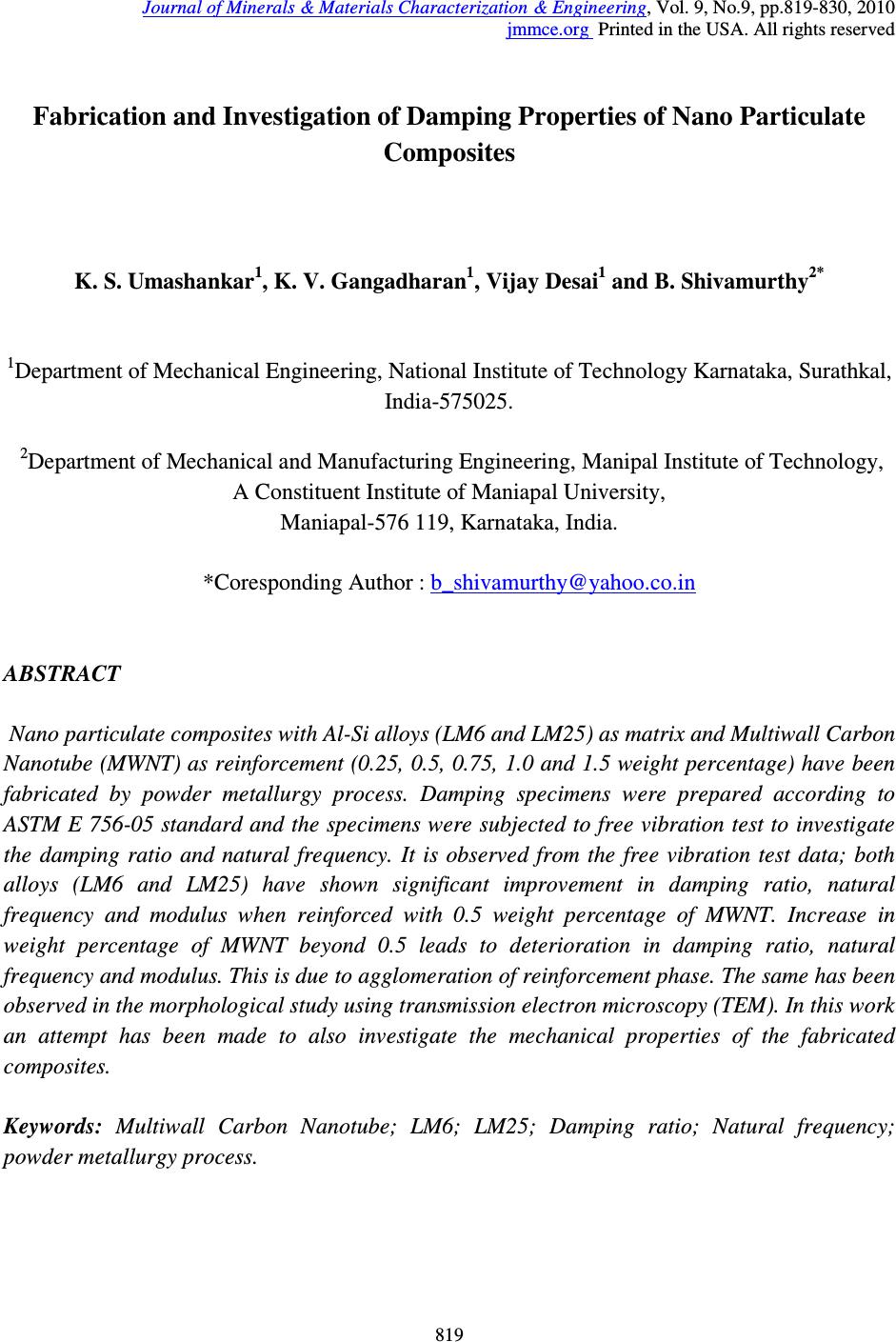

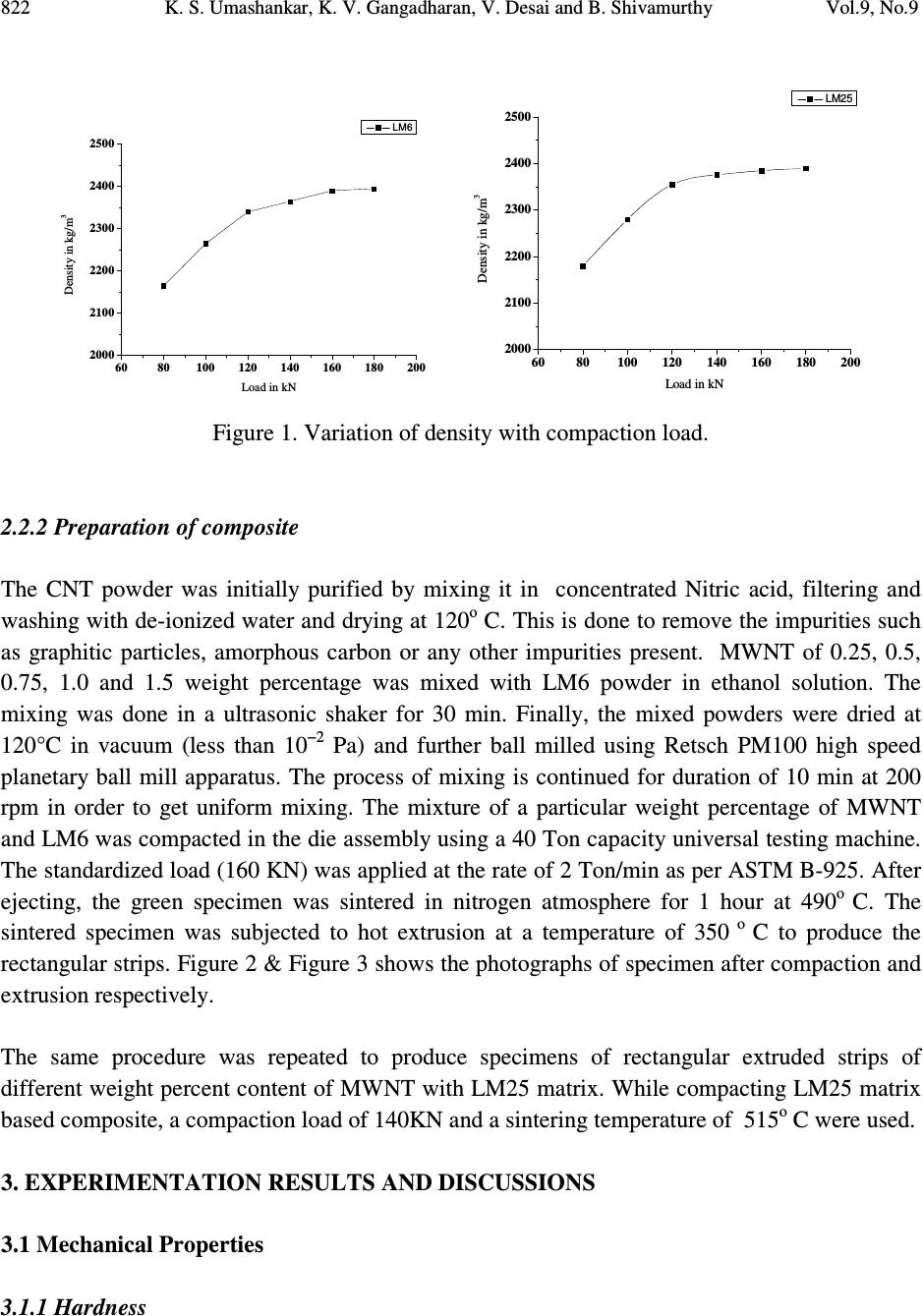

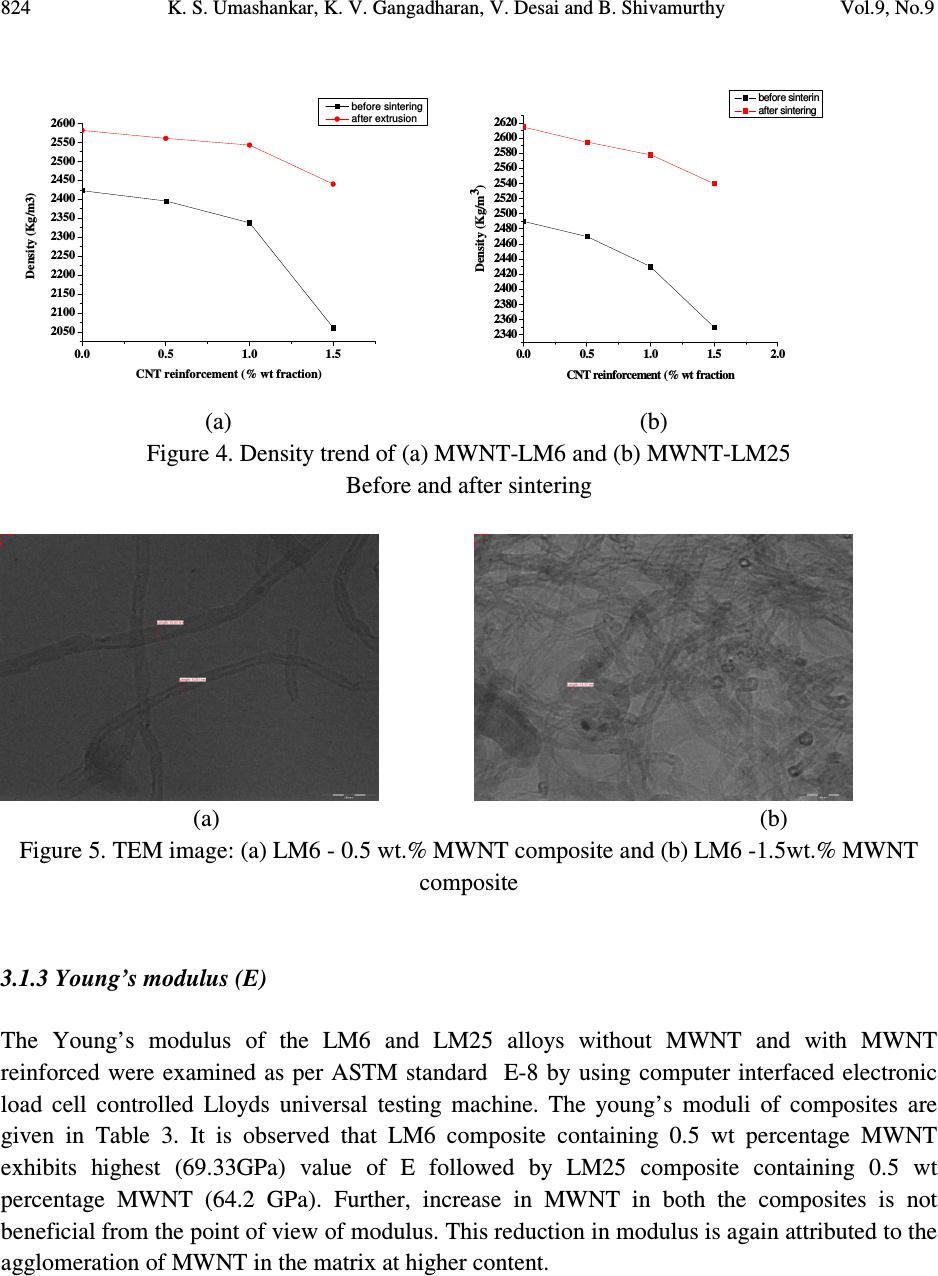

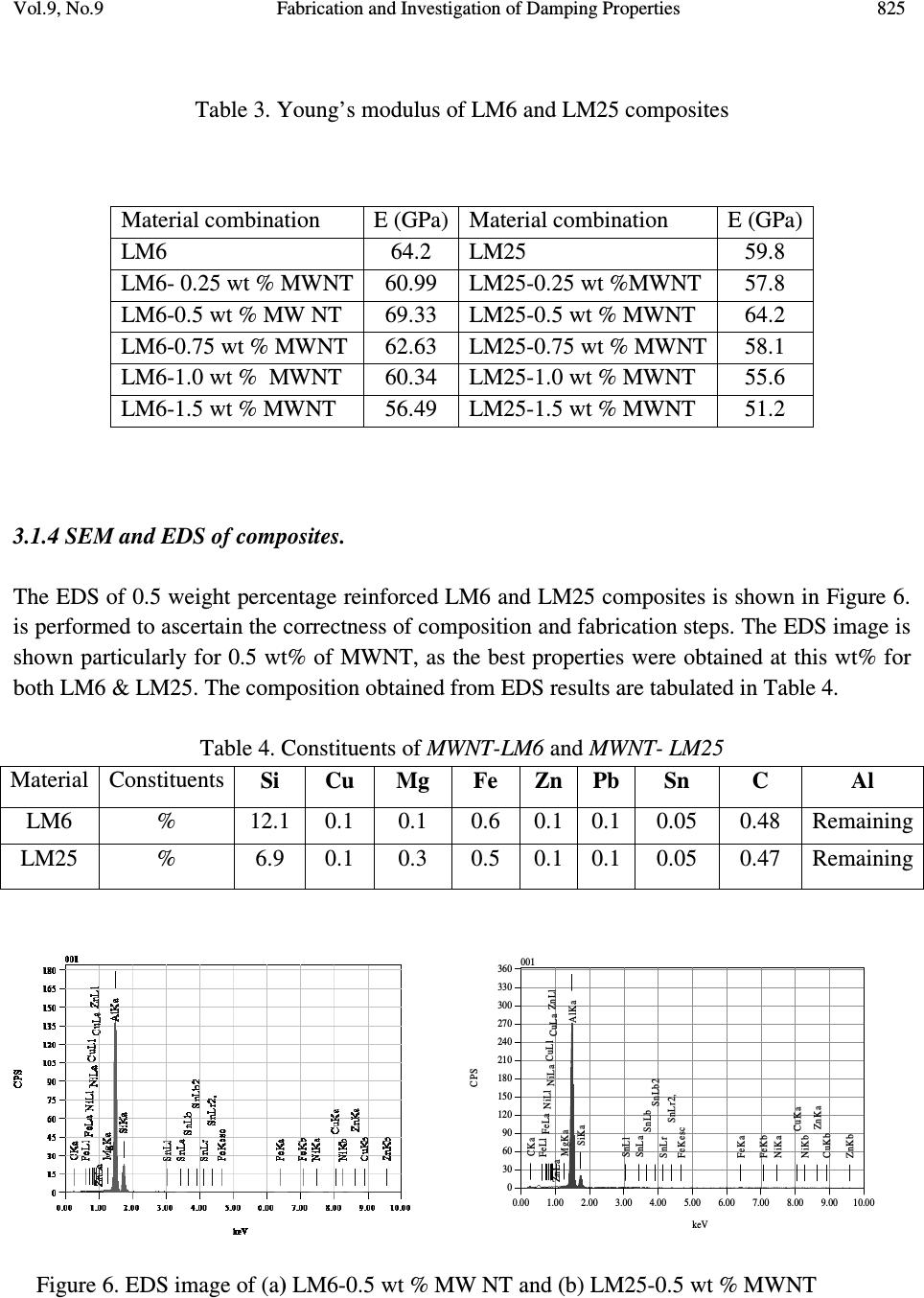

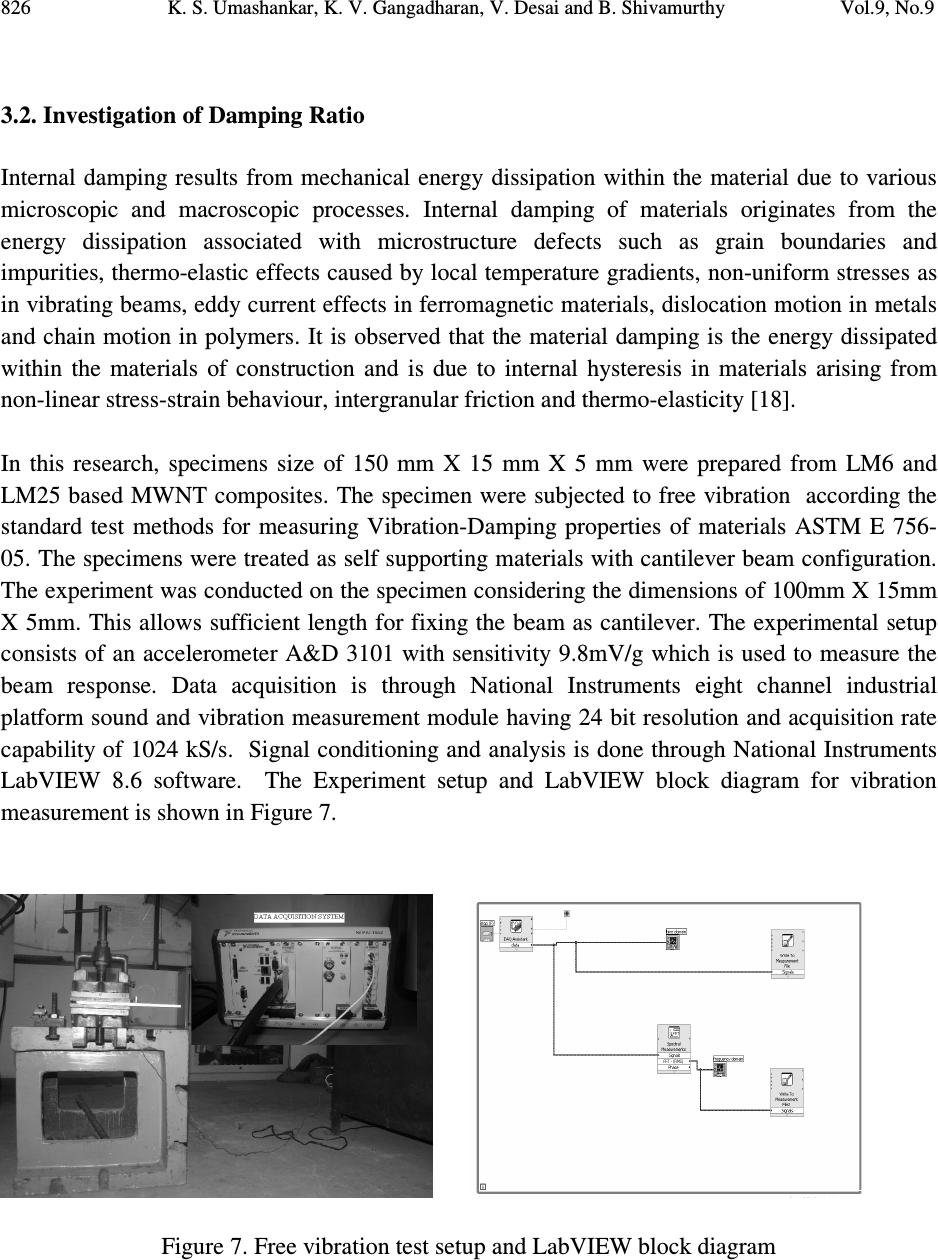

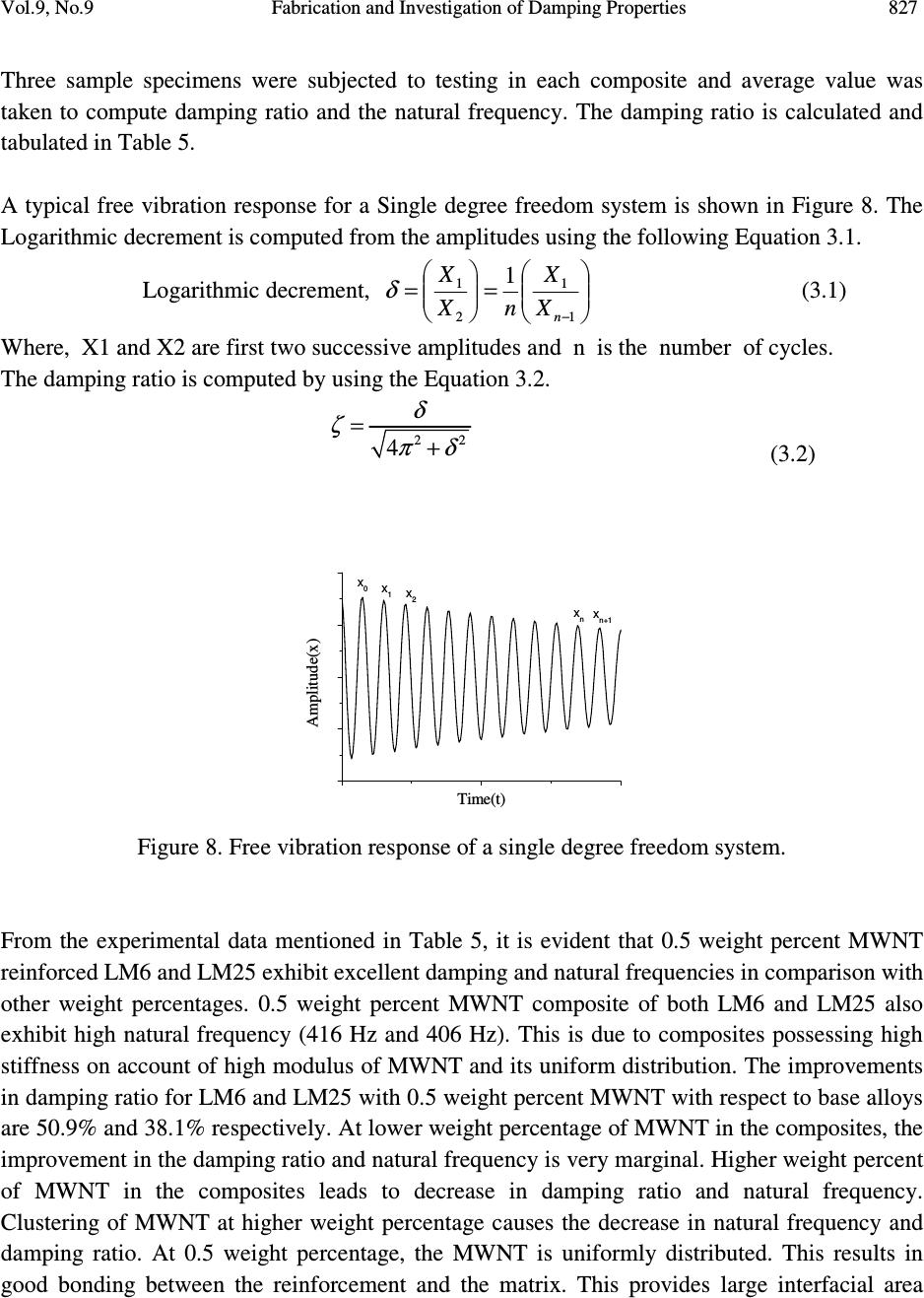

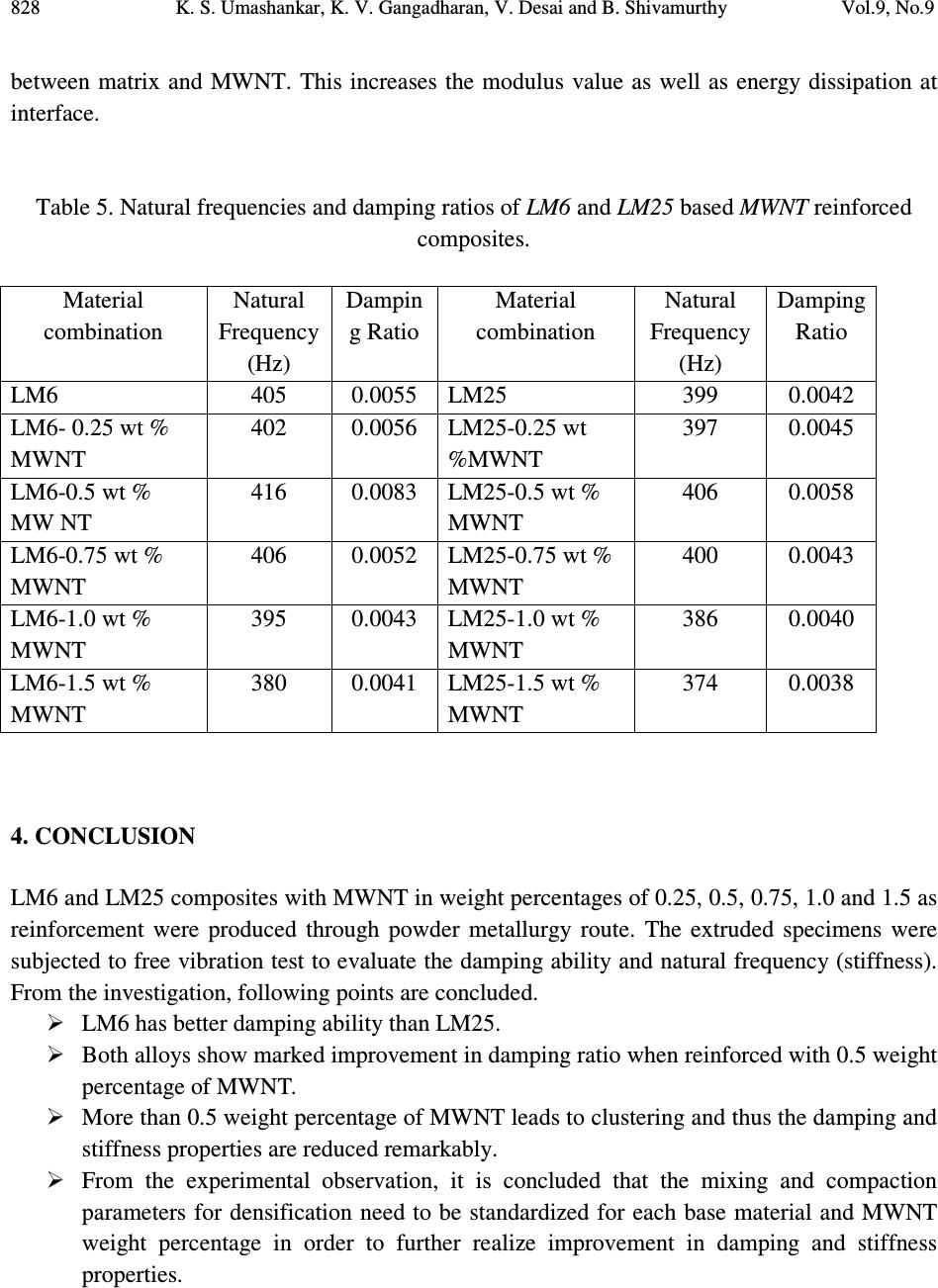

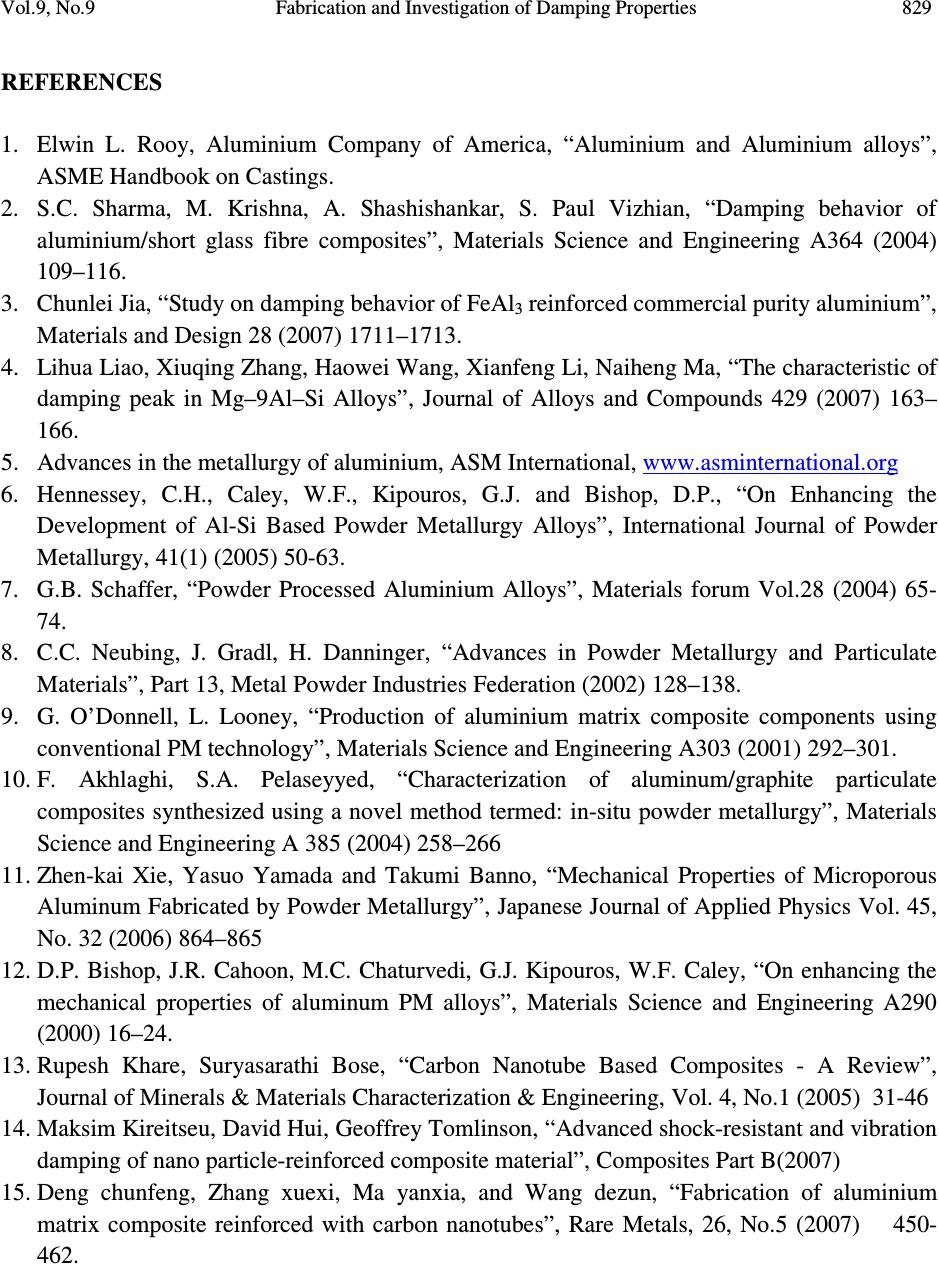

Journal of Minerals & Materials Characterization & Engineering, Vol. 9, No.9, pp.819-830, 2010 jmmce.org Printed in the USA. All rights reserved 819 Fabrication and Investigation of Damping Properties of Nano Particulate Composites K. S. Umashankar 1 , K. V. Gangadharan 1 , Vijay Desai 1 and B. Shivamurthy 2* 1 Department of Mechanical Engineering, National Institute of Technology Karnataka, Surathkal, India-575025. 2 Department of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering, Manipal Institute of Technology, A Constituent Institute of Maniapal University, Maniapal-576 119, Karnataka, India. *Coresponding Author : b_shivamurthy@yahoo.co.in ABSTRACT Nano particulate composites with Al-Si alloys (LM6 and LM25) as matrix and Multiwall Carbon Nanotube (MWNT) as reinforcement (0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0 and 1.5 weight percentage) have been fabricated by powder metallurgy process. Damping specimens were prepared according to ASTM E 756-05 standard and the specimens were subjected to free vibration test to investigate the damping ratio and natural frequency. It is observed from the free vibration test data; both alloys (LM6 and LM25) have shown significant improvement in damping ratio, natural frequency and modulus when reinforced with 0.5 weight percentage of MWNT. Increase in weight percentage of MWNT beyond 0.5 leads to deterioration in damping ratio, natural frequency and modulus. This is due to agglomeration of reinforcement phase. The same has been observed in the morphological study using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). In this work an attempt has been made to also investigate the mechanical properties of the fabricated composites. Keywords: Multiwall Carbon Nanotube; LM6; LM25; Damping ratio; Natural frequency; powder metallurgy process.  820 K. S. Umashankar, K. V. Gangadharan, V. Desai and B. Shivamurthy Vol.9, No.9 1. INTRODUCTION In aviation, automobile and other structural applications, the demand for materials possessing superior properties like higher strength to weight ratio, high modulus and high temperature stability along with good damping ability is continuously increases. However, it is difficult to achieve all these properties in a single material. This is one of the driving force for the development of newer and newer composite materials. In this context many researchers all over the world investigating new composite materials using either polymer matrix or metal matrix with different reinforcements. For components used at higher operating temperatures, metal matrix composite materials with a good reinforcement are preferred. In general, aluminium (Al) and its alloys have emerged as one of the most dominant metal matrix materials in the 21 st century [1]. This is because of their attractive mechanical properties [2, 3]. Among the Al alloys, Aluminium-Silicon (Al-Si) alloys in particular have been utilized significantly for engineering applications due to their better mechanical and physical properties. They also possess good manufacturing ability and lower density than Al [4]. This reduces weight and results in energy savings in automotive and aerospace applications. Many researchers have studied varieties of reinforcements with aluminum matrix to produce Metal Matrix Composites (MMCs) to achieve the required properties. Out of these reinforcements, Carbon Nano Tubes (CNT) is an ideal reinforcement since it possesses extremely high modulus of elasticity, strength, stiffness, low density and high specific surface area. MMCs are generally fabricated through processes such as casting, extrusion and powder metallurgy (P/M). Out of these, P/M process is regarded as one of the important processing techniques on account of homogeneity in composition and microstructure, minimum scrap, consistent porosity and close dimensional tolerances. P/M process also gives ample scope to produce wide variety of alloying systems and metal matrix composites [5-8]. With this insight it has been reported that, Al based particle reinforced composites produced by P/M process exhibit attractive mechanical properties such as increased stiffness, low density, good specific strength and vibration damping [9-12]. However literature studies indicate that major works have been carried out on polymer and ceramic based CNT reinforced composites [13]. When appropriate quantity of nanotubes is mixed with polymers, they show improved mechanical properties without sacrificing any other base properties [14]. Many researchers have also produced and characterized the Carbon nanotube based Aluminium metal matrix composites by powder metallurgy process [15-17] and it has been reported that Powder metallurgy process is one of the better processing techniques for these kinds of metal matrix composites. In the present work MWNT reinforced Al-Si alloy (LM6 and LM25) based composites are produced by powder metallurgy process and their mechanical and damping properties have been investigated.  Vol.9, No.9 Fabrication and Investigation of Damping Properties 821 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS 2.1 Materials Two types of nano particulate reinforced Al-Si composites were manufactured by using LM6 and LM25 powders of 200 mesh size as a matrix and MWNT as reinforcement. LM6 and LM25 were supplied by M/s Metal Powder. Co Ltd, Chennai, and the research grade MWNT was supplied by M/s Sigma Aldrich, Bangalore. The properties of as supplied MWNTs are given in Table.1. Table.1: Properties of MWNT Properties Values Purity Carbon > 90% (trace metal basis) OD × ID × L 10-15 nm × 2-6 nm × 0.1-10 µm Total Impurities Amorphous carbon, none detected by transmission electron microscope (TEM)) Melting Point 3652-3697 °C Density ~2.1 g/ml at 25 °C 2.2 Methods 2.2.1 Establishment of compaction load In order to achieve optimal compaction density, trial compactions were done at different loads for both LM6 and LM25 powders. A cylindrical die of 25.4 mm diameter was used to obtain cylindrical specimen as per ASTM B-925. A coating of zinc stearate was applied to the die and punch to minimize friction during the compaction process. 35 grams of metal powder was taken in the die and load was applied through a hydraulic press of 40 Ton capacity at the rate of 2 Ton/min. After compaction, the specimen was ejected and its volume was measured. The density was determined by mass-volume relation. The variation of density versus load for LM6 and LM25 are shown in Figure 1. From the densification trend it is observed that optimum density obtained at a compaction load of around 160 KN and 140 KN for LM6 and LM25 respectively.  822 K. S. Umashankar, K. V. Gangadharan, V. Desai and B. Shivamurthy Vol.9, No.9 6080100 120 140 160 180 200 2000 2100 2200 2300 2400 2500 Density in kg/m 3 Load in kN LM6 6080100 120 140 160 180 200 2000 2100 2200 2300 2400 2500 Density in kg/m 3 Load in kN LM25 Figure 1. Variation of density with compaction load. 2.2.2 Preparation of composite The CNT powder was initially purified by mixing it in concentrated Nitric acid, filtering and washing with de-ionized water and drying at 120 o C. This is done to remove the impurities such as graphitic particles, amorphous carbon or any other impurities present. MWNT of 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0 and 1.5 weight percentage was mixed with LM6 powder in ethanol solution. The mixing was done in a ultrasonic shaker for 30 min. Finally, the mixed powders were dried at 120°C in vacuum (less than 10 −2 Pa) and further ball milled using Retsch PM100 high speed planetary ball mill apparatus. The process of mixing is continued for duration of 10 min at 200 rpm in order to get uniform mixing. The mixture of a particular weight percentage of MWNT and LM6 was compacted in the die assembly using a 40 Ton capacity universal testing machine. The standardized load (160 KN) was applied at the rate of 2 Ton/min as per ASTM B-925. After ejecting, the green specimen was sintered in nitrogen atmosphere for 1 hour at 490 o C. The sintered specimen was subjected to hot extrusion at a temperature of 350 o C to produce the rectangular strips. Figure 2 & Figure 3 shows the photographs of specimen after compaction and extrusion respectively. The same procedure was repeated to produce specimens of rectangular extruded strips of different weight percent content of MWNT with LM25 matrix. While compacting LM25 matrix based composite, a compaction load of 140KN and a sintering temperature of 515 o C were used. 3. EXPERIMENTATION RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS 3.1 Mechanical Properties 3.1.1 Hardness  Vol.9, No.9 Fabrication and Investigation of Damping Properties 823 Figure 2. Cylindrical Specimen after compaction. Figure 3. Specimen c/s after extrusion. Hardness of specimen of base alloys (LM6 and LM25) and MWNT reinforced composites were determined by using Rockwell Hardness Testing apparatus as per ASTM B-925. The results are tabulated in Table 2. It is found that both for LM6 and LM25 based composites, the hardness increases with the addition of MWNT upto 0.5 wt % of MWNT and then the hardness decreases beyond 0.5 wt%. However, the hardness of LM6 composites is slightly on higher side compared to LM25 composites. This is due to the contribution of metallurgical composition and structure of base material LM6. Table 2. Hardness values of green and sintered compacts. Material Load (Ton) Hardness (RHN) Before sintering Hardness (RHN) After sintering For 0.25 wt % MWNT For 0.50 wt % MWNT For 0.75 wt % MWNT LM6 160 18 33 39 48 44 LM25 140 17 30 35 43 39 3.1.2. Density Density of the LM6 and LM25 base alloys and their composite before and after sintering were computed by mass-volume relation and plotted against wt% of CNT. The variation in density is shown in Figure 4. The density decreases with an increase in weight percentage of MWNT in the composites, both before and after sintering. It has also been observed that, the density decreased remarkably in both LM6 and LM25 based composites at above 1.0 weight percent of reinforcement. This is due to agglomeration of MWNT in the matrix. The agglomeration of CNT is well supported by the TEM images, shown in Figure 5.  824 K. S. Umashankar, K. V. Gangadharan, V. Desai and B. Shivamurthy Vol.9, No.9 0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2050 2100 2150 2200 2250 2300 2350 2400 2450 2500 2550 2600 Density (Kg/m3) CNT reinforcement (% wt fraction) before sintering after extrusion 0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2340 2360 2380 2400 2420 2440 2460 2480 2500 2520 2540 2560 2580 2600 2620 Density (Kg/m3) CNT reinforcement (% wt fraction before sinterin after sintering (a) (b) Figure 4. Density trend of (a) MWNT-LM6 and (b) MWNT-LM25 Before and after sintering (a) (b) Figure 5. TEM image: (a) LM6 - 0.5 wt.% MWNT composite and (b) LM6 -1.5wt.% MWNT composite 3.1.3 Young’s modulus (E) The Young’s modulus of the LM6 and LM25 alloys without MWNT and with MWNT reinforced were examined as per ASTM standard E-8 by using computer interfaced electronic load cell controlled Lloyds universal testing machine. The young’s moduli of composites are given in Table 3. It is observed that LM6 composite containing 0.5 wt percentage MWNT exhibits highest (69.33GPa) value of E followed by LM25 composite containing 0.5 wt percentage MWNT (64.2 GPa). Further, increase in MWNT in both the composites is not beneficial from the point of view of modulus. This reduction in modulus is again attributed to the agglomeration of MWNT in the matrix at higher content.  Vol.9, No.9 Fabrication and Investigation of Damping Properties 825 Table 3. Young’s modulus of LM6 and LM25 composites 3.1.4 SEM and EDS of composites. The EDS of 0.5 weight percentage reinforced LM6 and LM25 composites is shown in Figure 6. is performed to ascertain the correctness of composition and fabrication steps. The EDS image is shown particularly for 0.5 wt% of MWNT, as the best properties were obtained at this wt% for both LM6 & LM25. The composition obtained from EDS results are tabulated in Table 4. Table 4. Constituents of MWNT-LM6 and MWNT- LM25 Material Constituents Si Cu Mg Fe Zn Pb Sn C Al LM6 % 12.1 0.1 0.1 0.6 0.1 0.1 0.05 0.48 Remaining LM25 % 6.9 0.1 0.3 0.5 0.1 0.1 0.05 0.47 Remaining Figure 6. EDS image of (a) LM6-0.5 wt % MW NT and (b) LM25-0.5 wt % MWNT Material combination E (GPa) Material combination E (GPa) LM6 64.2 LM25 59.8 LM6- 0.25 wt % MWNT 60.99 LM25-0.25 wt %MWNT 57.8 LM6-0.5 wt % MW NT 69.33 LM25-0.5 wt % MWNT 64.2 LM6-0.75 wt % MWNT 62.63 LM25-0.75 wt % MWNT 58.1 LM6-1.0 wt % MWNT 60.34 LM25-1.0 wt % MWNT 55.6 LM6-1.5 wt % MWNT 56.49 LM25-1.5 wt % MWNT 51.2 0.00 1.00 2.00 3.00 4.00 5.00 6.007.00 8.00 9.0010.00 keV 001 0 30 60 90 120 150 180 210 240 270 300 330 360 CPS CKa MgKa AlKa SiKa FeLl FeLa FeKesc FeKa FeKb NiLl NiLa NiKa NiKb CuLlCuLa CuKa CuKb ZnLl ZnLa ZnKa ZnKb SnLl SnLa SnLb SnLb2 SnLr SnLr2,  826 K. S. Umashankar, K. V. Gangadharan, V. Desai and B. Shivamurthy Vol.9, No.9 3.2. Investigation of Damping Ratio Internal damping results from mechanical energy dissipation within the material due to various microscopic and macroscopic processes. Internal damping of materials originates from the energy dissipation associated with microstructure defects such as grain boundaries and impurities, thermo-elastic effects caused by local temperature gradients, non-uniform stresses as in vibrating beams, eddy current effects in ferromagnetic materials, dislocation motion in metals and chain motion in polymers. It is observed that the material damping is the energy dissipated within the materials of construction and is due to internal hysteresis in materials arising from non-linear stress-strain behaviour, intergranular friction and thermo-elasticity [18]. In this research, specimens size of 150 mm X 15 mm X 5 mm were prepared from LM6 and LM25 based MWNT composites. The specimen were subjected to free vibration according the standard test methods for measuring Vibration-Damping properties of materials ASTM E 756- 05. The specimens were treated as self supporting materials with cantilever beam configuration. The experiment was conducted on the specimen considering the dimensions of 100mm X 15mm X 5mm. This allows sufficient length for fixing the beam as cantilever. The experimental setup consists of an accelerometer A&D 3101 with sensitivity 9.8mV/g which is used to measure the beam response. Data acquisition is through National Instruments eight channel industrial platform sound and vibration measurement module having 24 bit resolution and acquisition rate capability of 1024 kS/s. Signal conditioning and analysis is done through National Instruments LabVIEW 8.6 software. The Experiment setup and LabVIEW block diagram for vibration measurement is shown in Figure 7. Figure 7. Free vibration test setup and LabVIEW block diagram  Vol.9, No.9 Fabrication and Investigation of Damping Properties 827 Three sample specimens were subjected to testing in each composite and average value was taken to compute damping ratio and the natural frequency. The damping ratio is calculated and tabulated in Table 5. A typical free vibration response for a Single degree freedom system is shown in Figure 8. The Logarithmic decrement is computed from the amplitudes using the following Equation 3.1. Logarithmic decrement, = = −1 1 2 1 1 n X X nX X δ (3.1) Where, X1 and X2 are first two successive amplitudes and n is the number of cycles. The damping ratio is computed by using the Equation 3.2. 2 2 4 δ ζ π δ = + (3.2) x n+1 x n x 2 x 1 Amplitude(x) Time(t) x 0 Figure 8. Free vibration response of a single degree freedom system. From the experimental data mentioned in Table 5, it is evident that 0.5 weight percent MWNT reinforced LM6 and LM25 exhibit excellent damping and natural frequencies in comparison with other weight percentages. 0.5 weight percent MWNT composite of both LM6 and LM25 also exhibit high natural frequency (416 Hz and 406 Hz). This is due to composites possessing high stiffness on account of high modulus of MWNT and its uniform distribution. The improvements in damping ratio for LM6 and LM25 with 0.5 weight percent MWNT with respect to base alloys are 50.9% and 38.1% respectively. At lower weight percentage of MWNT in the composites, the improvement in the damping ratio and natural frequency is very marginal. Higher weight percent of MWNT in the composites leads to decrease in damping ratio and natural frequency. Clustering of MWNT at higher weight percentage causes the decrease in natural frequency and damping ratio. At 0.5 weight percentage, the MWNT is uniformly distributed. This results in good bonding between the reinforcement and the matrix. This provides large interfacial area  828 K. S. Umashankar, K. V. Gangadharan, V. Desai and B. Shivamurthy Vol.9, No.9 between matrix and MWNT. This increases the modulus value as well as energy dissipation at interface. Table 5. Natural frequencies and damping ratios of LM6 and LM25 based MWNT reinforced composites. 4. CONCLUSION LM6 and LM25 composites with MWNT in weight percentages of 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0 and 1.5 as reinforcement were produced through powder metallurgy route. The extruded specimens were subjected to free vibration test to evaluate the damping ability and natural frequency (stiffness). From the investigation, following points are concluded. LM6 has better damping ability than LM25. Both alloys show marked improvement in damping ratio when reinforced with 0.5 weight percentage of MWNT. More than 0.5 weight percentage of MWNT leads to clustering and thus the damping and stiffness properties are reduced remarkably. From the experimental observation, it is concluded that the mixing and compaction parameters for densification need to be standardized for each base material and MWNT weight percentage in order to further realize improvement in damping and stiffness properties. Material combination Natural Frequency (Hz) Dampin g Ratio Material combination Natural Frequency (Hz) Damping Ratio LM6 405 0.0055 LM25 399 0.0042 LM6- 0.25 wt % MWNT 402 0.0056 LM25-0.25 wt %MWNT 397 0.0045 LM6-0.5 wt % MW NT 416 0.0083 LM25-0.5 wt % MWNT 406 0.0058 LM6-0.75 wt % MWNT 406 0.0052 LM25-0.75 wt % MWNT 400 0.0043 LM6-1.0 wt % MWNT 395 0.0043 LM25-1.0 wt % MWNT 386 0.0040 LM6-1.5 wt % MWNT 380 0.0041 LM25-1.5 wt % MWNT 374 0.0038  Vol.9, No.9 Fabrication and Investigation of Damping Properties 829 REFERENCES 1. Elwin L. Rooy, Aluminium Company of America, “Aluminium and Aluminium alloys”, ASME Handbook on Castings. 2. S.C. Sharma, M. Krishna, A. Shashishankar, S. Paul Vizhian, “Damping behavior of aluminium/short glass fibre composites”, Materials Science and Engineering A364 (2004) 109–116. 3. Chunlei Jia, “Study on damping behavior of FeAl 3 reinforced commercial purity aluminium”, Materials and Design 28 (2007) 1711–1713. 4. Lihua Liao, Xiuqing Zhang, Haowei Wang, Xianfeng Li, Naiheng Ma, “The characteristic of damping peak in Mg–9Al–Si Alloys”, Journal of Alloys and Compounds 429 (2007) 163– 166. 5. Advances in the metallurgy of aluminium, ASM International, www.asminternational.org 6. Hennessey, C.H., Caley, W.F., Kipouros, G.J. and Bishop, D.P., “On Enhancing the Development of Al-Si Based Powder Metallurgy Alloys”, International Journal of Powder Metallurgy, 41(1) (2005) 50-63. 7. G.B. Schaffer, “Powder Processed Aluminium Alloys”, Materials forum Vol.28 (2004) 65- 74. 8. C.C. Neubing, J. Gradl, H. Danninger, “Advances in Powder Metallurgy and Particulate Materials”, Part 13, Metal Powder Industries Federation (2002) 128–138. 9. G. O’Donnell, L. Looney, “Production of aluminium matrix composite components using conventional PM technology”, Materials Science and Engineering A303 (2001) 292–301. 10. F. Akhlaghi, S.A. Pelaseyyed, “Characterization of aluminum/graphite particulate composites synthesized using a novel method termed: in-situ powder metallurgy”, Materials Science and Engineering A 385 (2004) 258–266 11. Zhen-kai Xie, Yasuo Yamada and Takumi Banno, “Mechanical Properties of Microporous Aluminum Fabricated by Powder Metallurgy”, Japanese Journal of Applied Physics Vol. 45, No. 32 (2006) 864–865 12. D.P. Bishop, J.R. Cahoon, M.C. Chaturvedi, G.J. Kipouros, W.F. Caley, “On enhancing the mechanical properties of aluminum PM alloys”, Materials Science and Engineering A290 (2000) 16–24. 13. Rupesh Khare, Suryasarathi Bose, “Carbon Nanotube Based Composites - A Review”, Journal of Minerals & Materials Characterization & Engineering, Vol. 4, No.1 (2005) 31-46 14. Maksim Kireitseu, David Hui, Geoffrey Tomlinson, “Advanced shock-resistant and vibration damping of nano particle-reinforced composite material”, Composites Part B(2007) 15. Deng chunfeng, Zhang xuexi, Ma yanxia, and Wang dezun, “Fabrication of aluminium matrix composite reinforced with carbon nanotubes”, Rare Metals, 26, No.5 (2007) 450- 462.  830 K. S. Umashankar, K. V. Gangadharan, V. Desai and B. Shivamurthy Vol.9, No.9 16. Chunfeng Deng, XueXi Zhang, Dezun Wang, Qiang Lin, Aibin Li, “Preparation and characterization of carbon nanotubes/aluminium matrix composites”, Materials Letters 61 (2007) 1725–1728. 17. H.J. Choi, G.B. Kwon, G.Y. Lee and D.H. Bae, “Reinforcement with carbon nanotubes in aluminium matrix composites”, Scripta Materialia, 59 (2008) 360–363. 18. Smith. J. W., “Vibration of structure: Applications in civil engineering design”, (1988) Chapman & Hall, London. |