Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

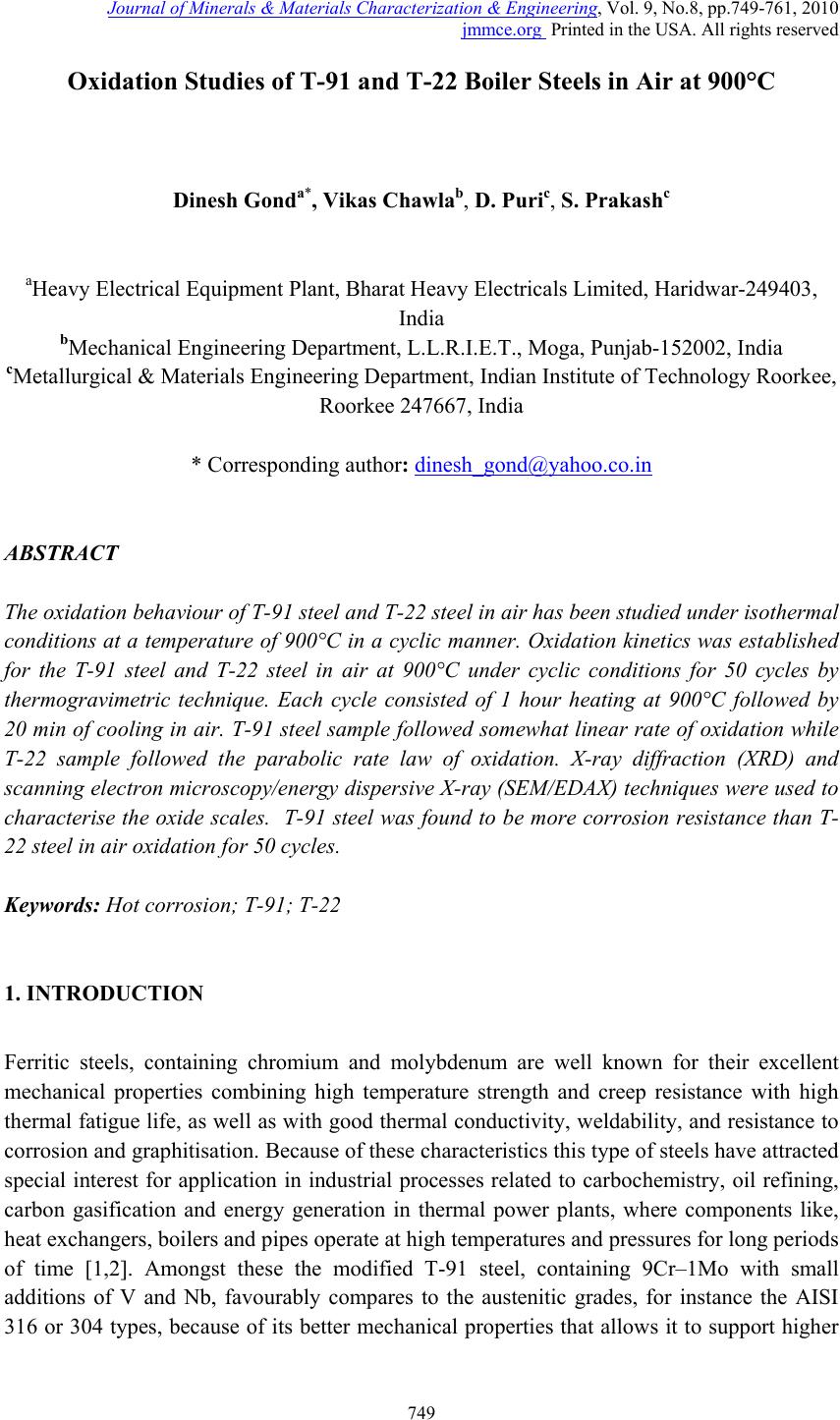

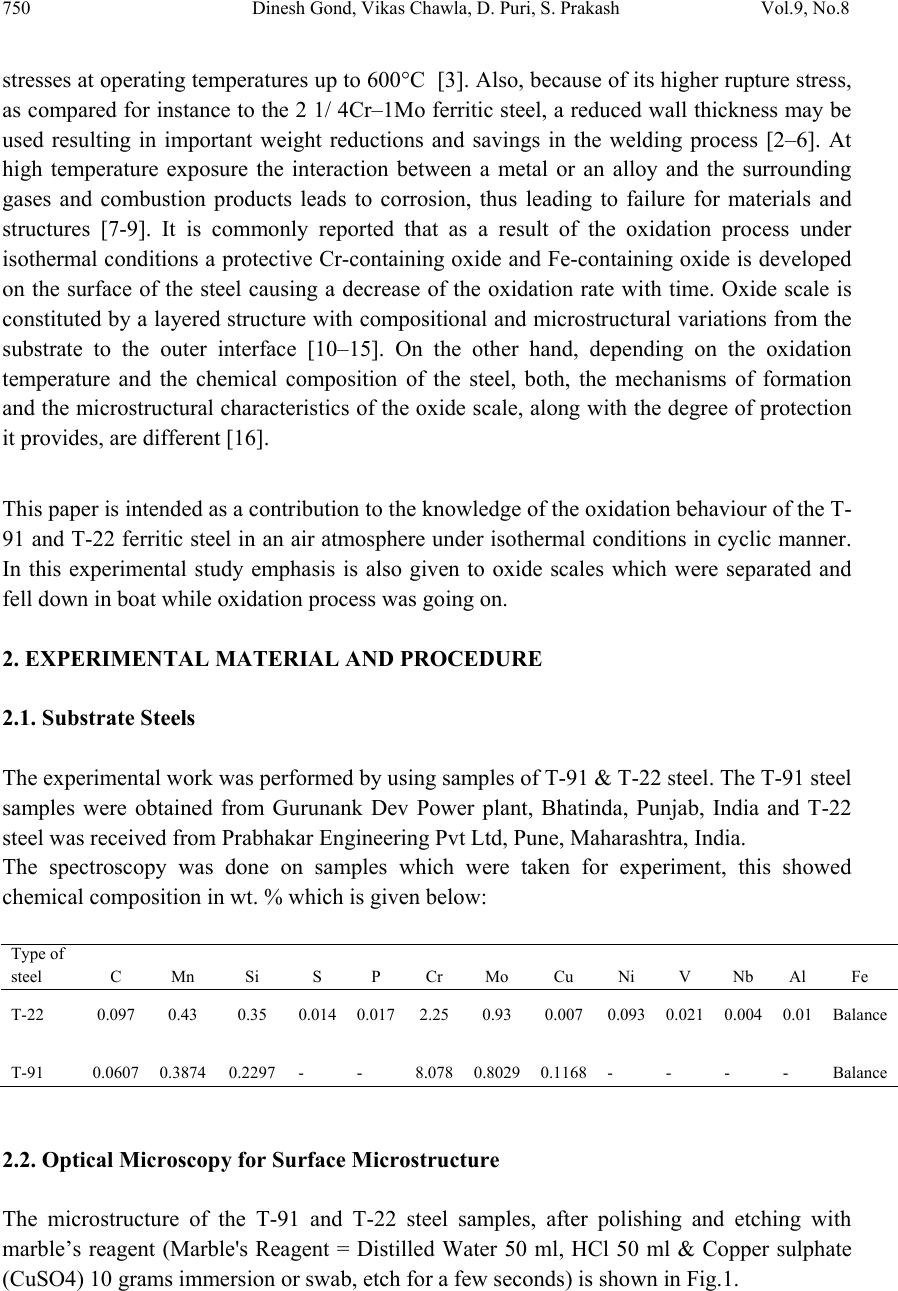

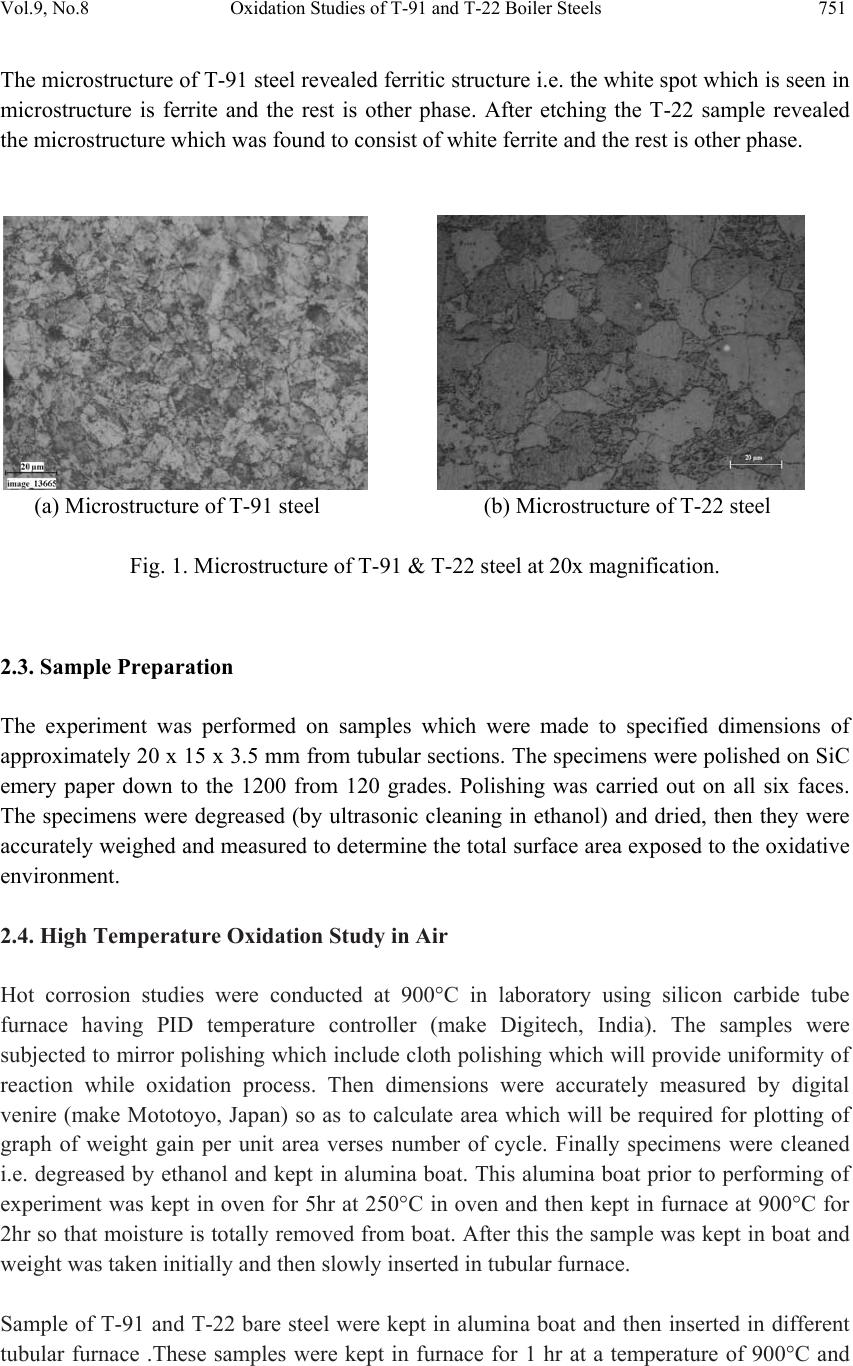

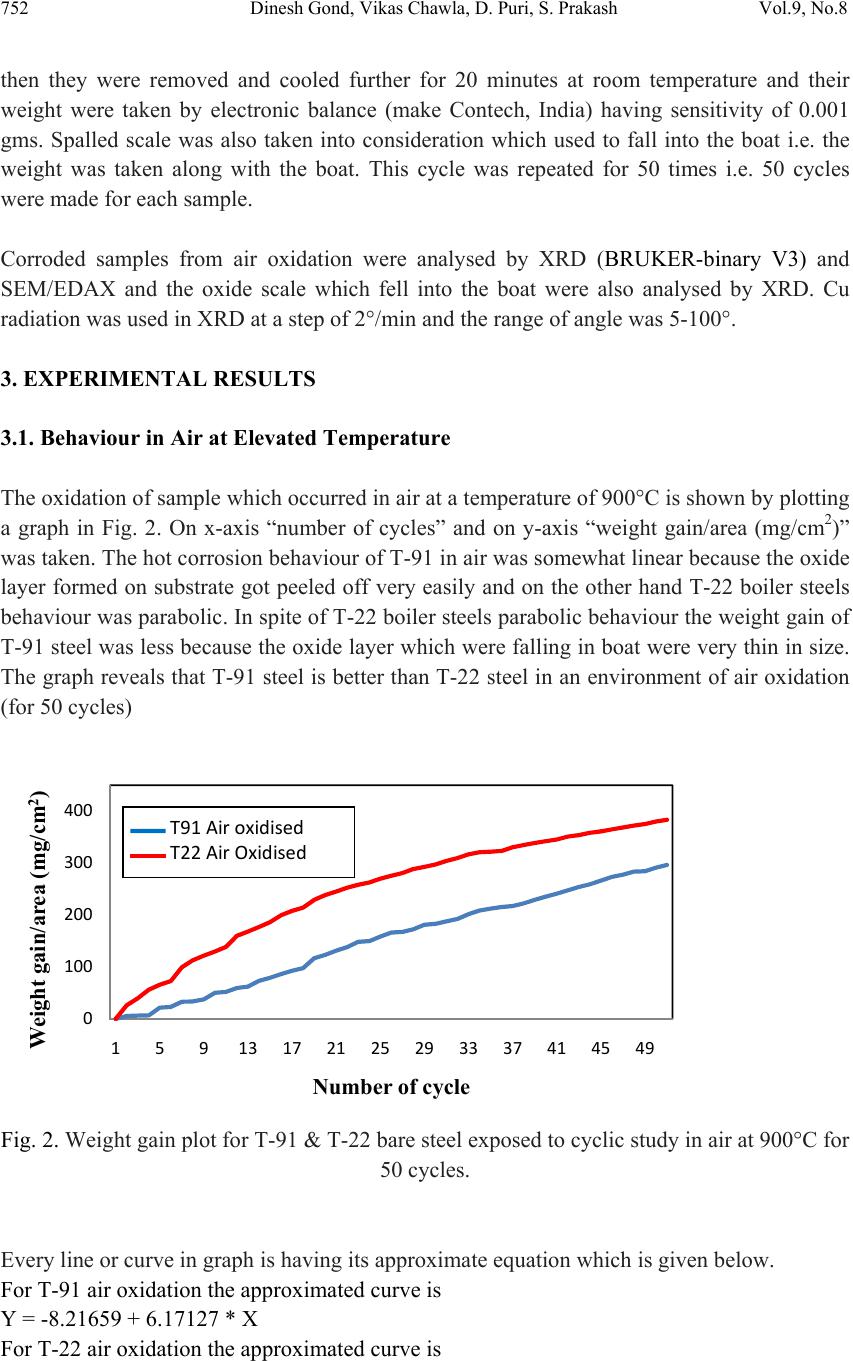

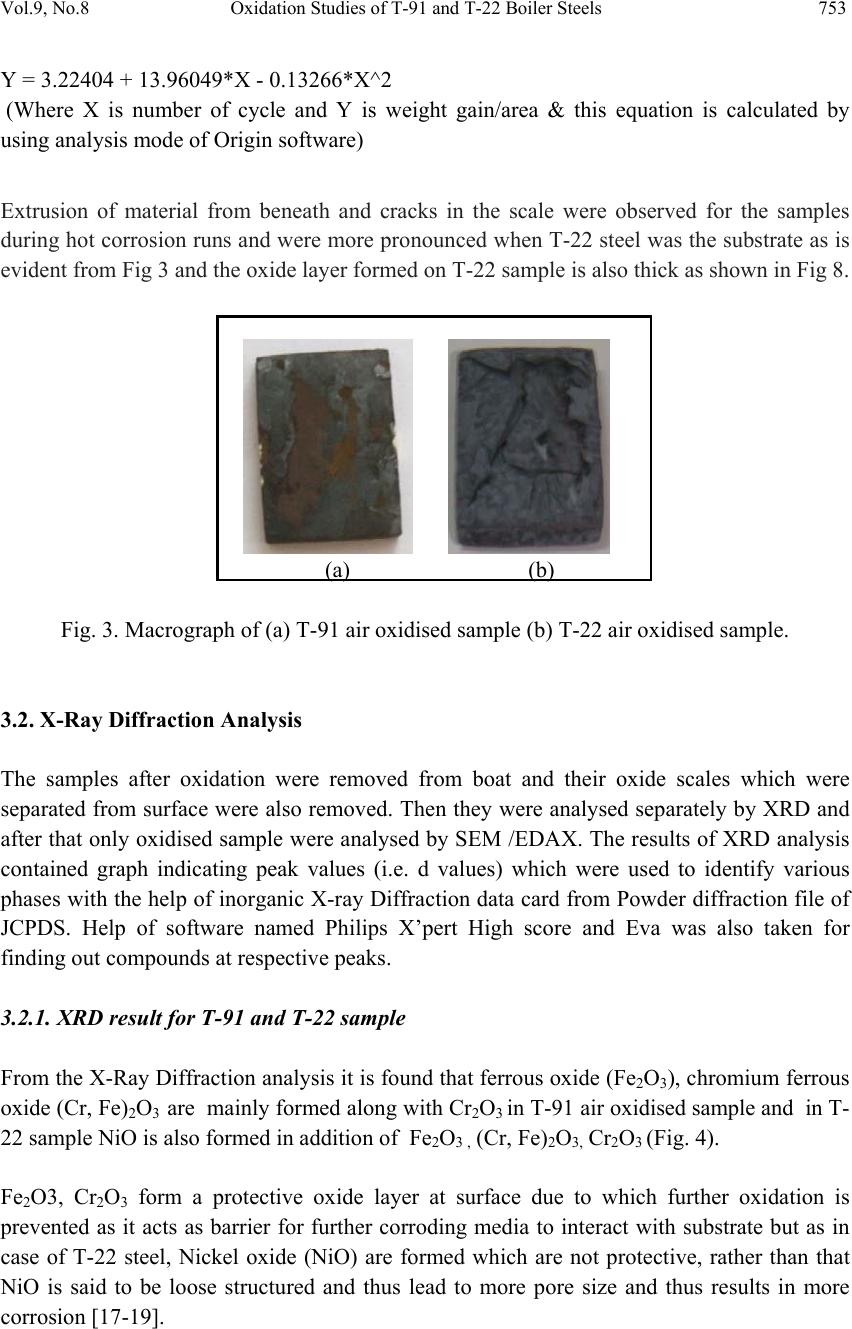

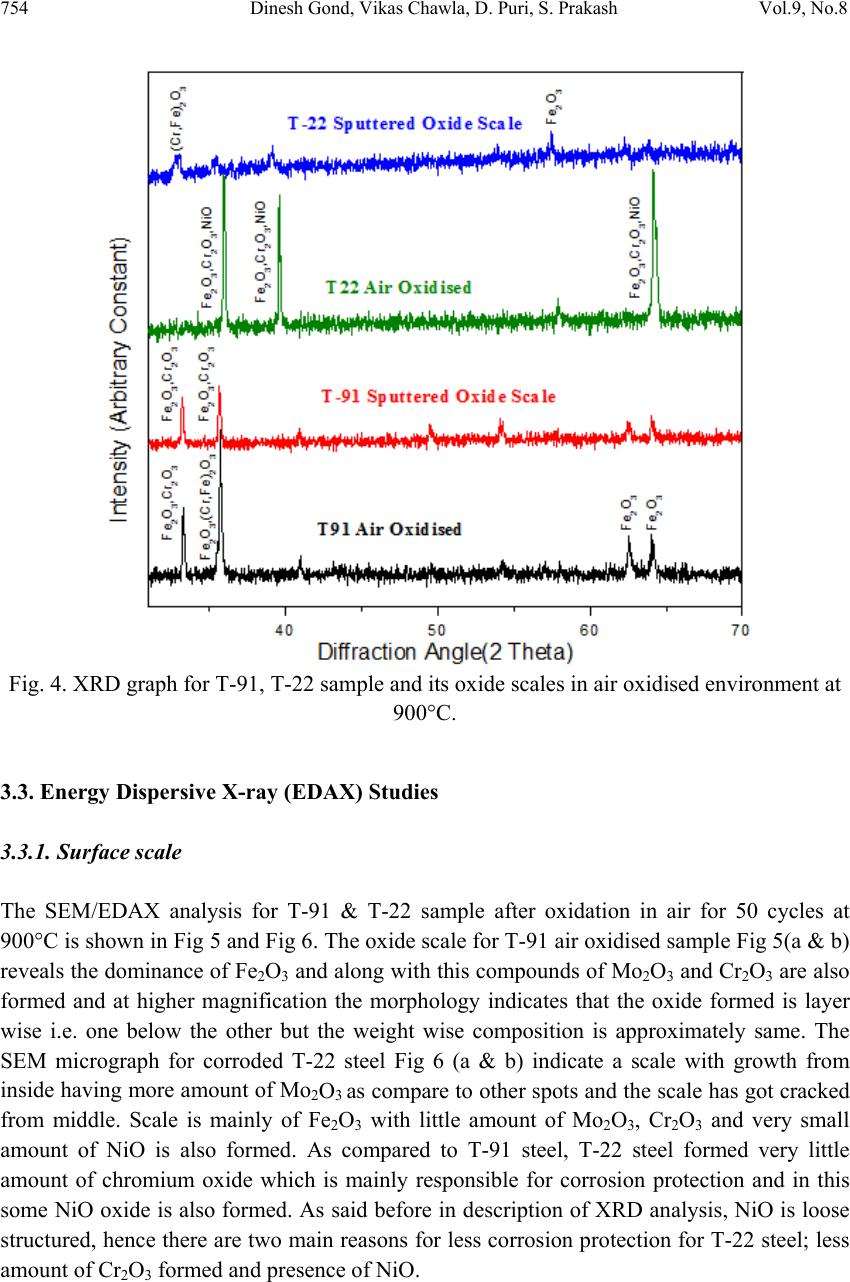

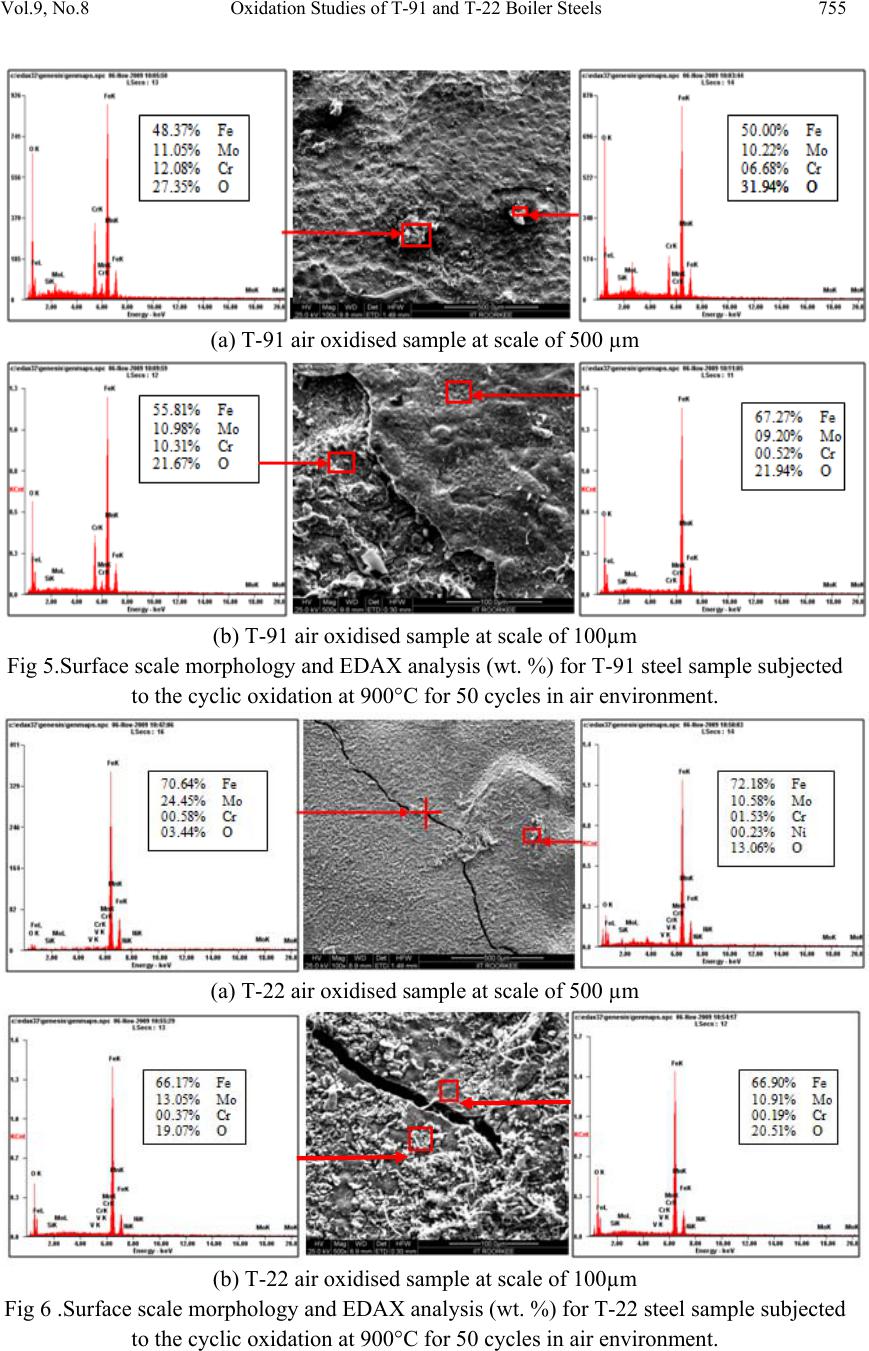

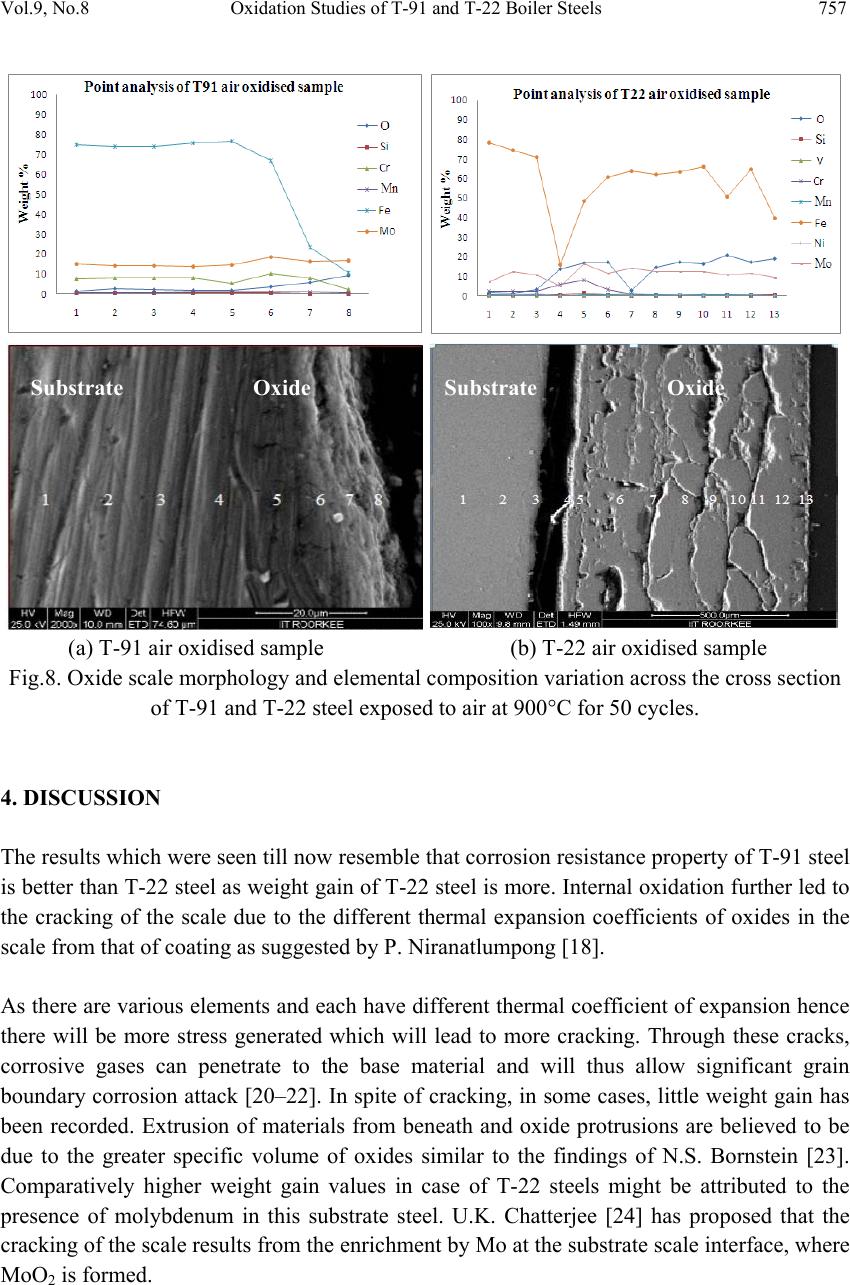

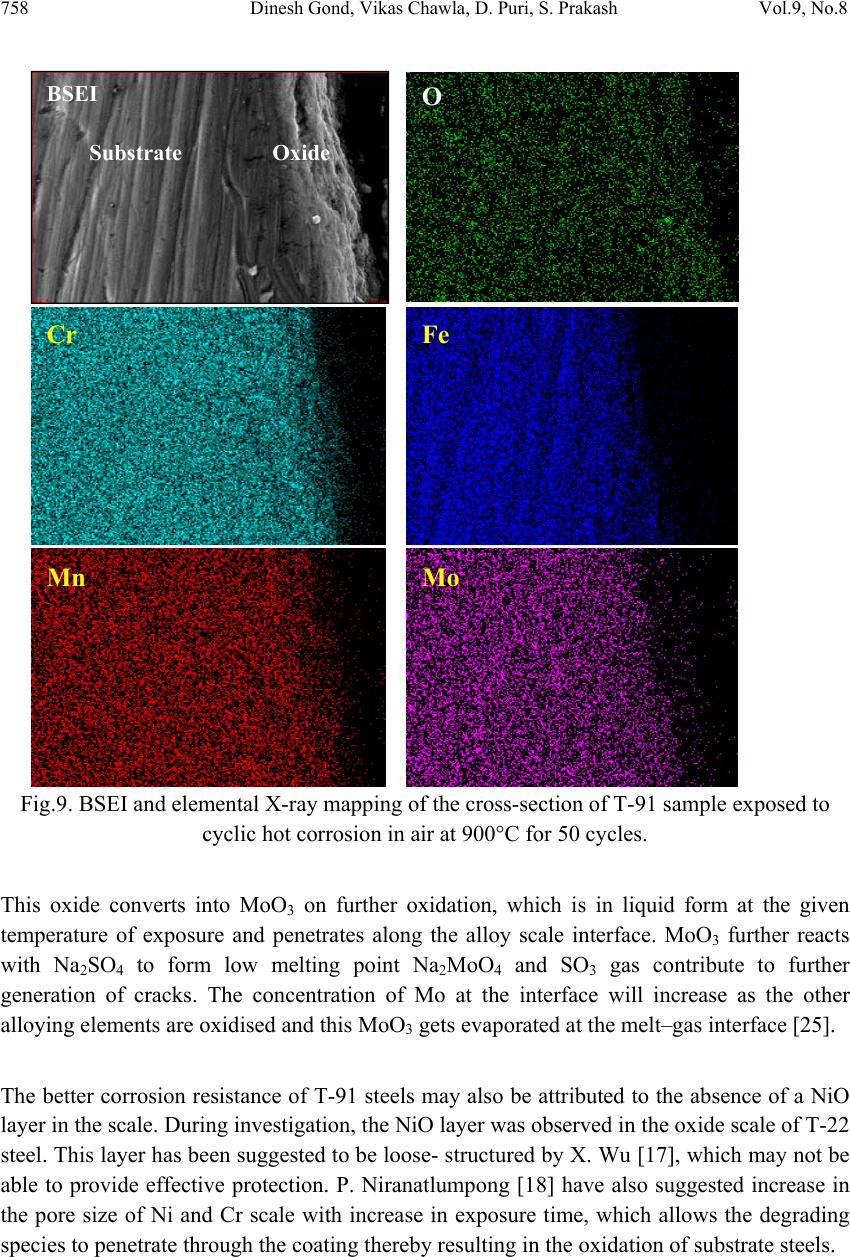

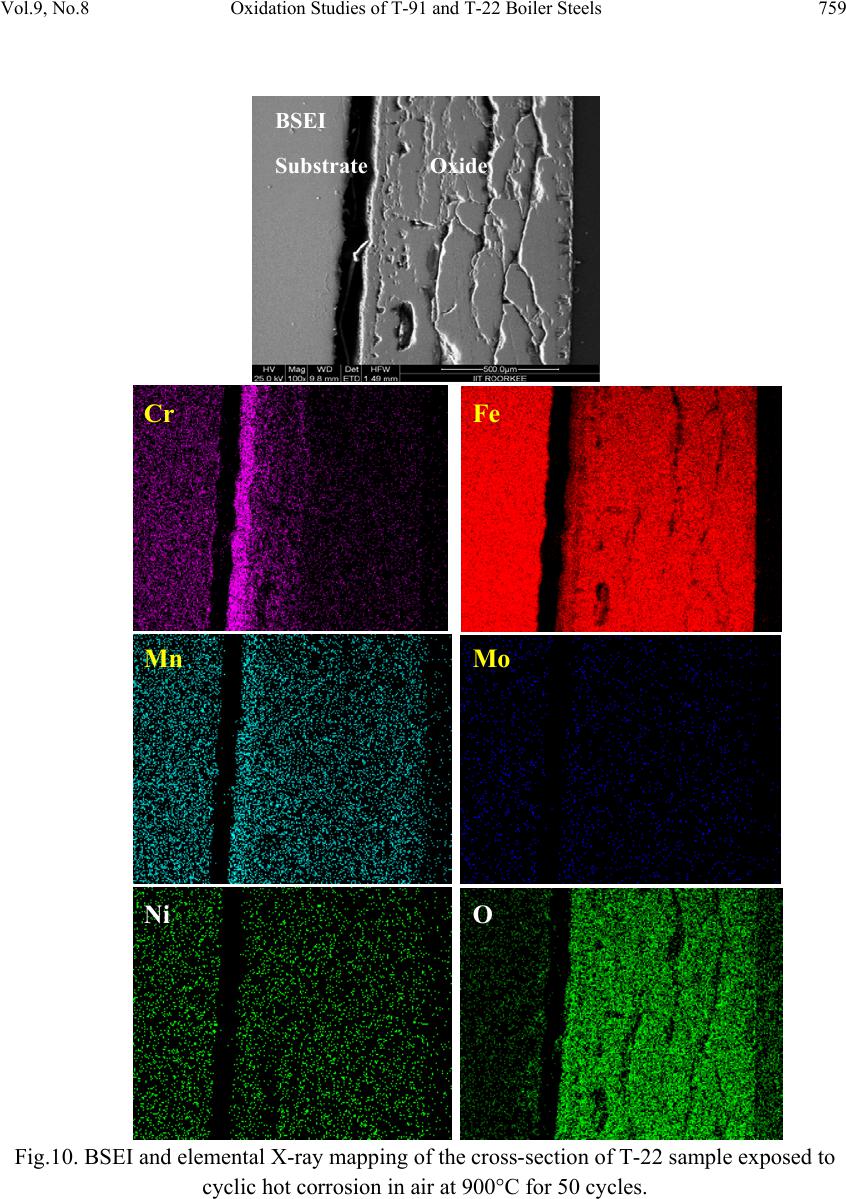

Journal of Minerals & Materials Characterization & Engineering, Vol. 9, No.8, pp.749-761, 2010 jmmce.org Printed in the USA. All rights reserved 749 Oxidation Studies of T-91 and T-22 Boiler Steels in Air at 900°C Dinesh Gonda*, Vikas Chawl ab, D. Puric, S. Prakashc aHeavy Electrical Equipment Plant, Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited, Haridwar-249403, India bMechanical Engineering Department, L.L.R.I.E.T., Moga, Punjab-152002, India cMetallurgical & Materials Engineering Department, Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee, Roorkee 247667, India * Corresponding author: dinesh_gond@yahoo.co.in ABSTRACT The oxidation behaviour of T-91 steel and T -22 steel in air ha s been studied und er iso thermal conditions at a temperature of 900°C in a cyclic manner. Oxidation kinetics was established for the T-91 steel and T-22 steel in air at 900°C under cyclic conditions for 50 cycles by thermogravimetric technique. Each cycle consisted of 1 hour heating at 900°C followed by 20 min of cooling in air. T-91 steel sample followed somewhat linear rate of oxidation while T-22 sample followed the parabolic rate law of oxidation. X-ray diffraction (XRD) and scanning electron microscopy/energy dispersive X-ray (SEM/EDAX) techniques were used to characterise the oxide scales. T-91 steel was found to be more corrosion resistance than T- 22 steel in air oxidation for 50 cycles. Keywords: Hot corrosion; T-91; T-22 1. INTRODUCTION Ferritic steels, containing chromium and molybdenum are well known for their excellent mechanical properties combining high temperature strength and creep resistance with high thermal fatigue life, as well as with good thermal conductivity, weldability, and resistance to corrosion and graphitisation. Because of these ch ar acteris ti cs thi s type of steel s have att ract ed special interest for application in industrial processes related to carbochemistry, oil refining, carbon gasification and energy generation in thermal power plants, where components like, heat exchangers, boilers and pipes operate at high temperatures and pressures for long periods of time [1,2]. Amongst these the modified T-91 steel, containing 9Cr–1Mo with small additions of V and Nb, favourably compares to the austenitic grades, for instance the AISI 316 or 304 types, because of its better mechanical properties that allows it to support higher  750 Dinesh Gond, Vikas Chawla, D. Puri, S. Prakash Vol.9, No.8 stresses at operating temperatures up to 600°C [3]. Also, because of its higher rupture stress, as compared for instance to the 2 1/ 4Cr–1Mo ferritic steel, a reduced wall thickness may be used resulting in important weight reductions and savings in the welding process [2–6]. At high temperature exposure the interaction between a metal or an alloy and the surrounding gases and combustion products leads to corrosion, thus leading to failure for materials and structures [7-9]. It is commonly reported that as a result of the oxidation process under isothermal conditions a protective Cr-containing oxide and Fe-containing oxide is developed on the surface of the steel causing a decrease of the oxidation rate with time. Oxide scale is constituted by a layered structure with compositional and microstructural variations from the substrate to the outer interface [10–15]. On the other hand, depending on the oxidation temperature and the chemical composition of the steel, both, the mechanisms of formation and the microstructural characteristics of the oxide scale, along with the degree of protection it provides, are different [16]. This paper is intended as a contribution to the knowledge of the oxidation behaviour of the T- 91 and T-22 ferritic steel in an air atmosphere under isothermal conditions in cyclic manner. In this experimental study emphasis is also given to oxide scales which were separated and fell down in boat while oxidation process was going on. 2. EXPERIMENTAL MATERIAL AND PROCEDURE 2.1. Substrate Steels The experimental work was performed by using samples of T-91 & T-22 steel. The T-91 steel samples were obtained from Gurunank Dev Power plant, Bhatinda, Punjab, India and T-22 steel was received from Prabhakar Engineering Pvt Ltd, Pune, Maharashtra, India. The spectroscopy was done on samples which were taken for experiment, this showed chemical composition in wt. % which is given below: Type of steel C Mn Si S P Cr Mo Cu Ni V Nb Al Fe T-22 0.097 0.43 0.35 0.014 0.017 2.25 0.93 0.007 0.093 0.021 0.004 0.01 Balance T-91 0.0607 0.3874 0.2297 - - 8.078 0.8029 0.1168 - - - - Balance 2.2. Optical Microscopy for Surface Microstructure The microstructure of the T-91 and T-22 steel samples, after polishing and etching with marble’s reagent (Marble's Reagent = Distilled Water 50 ml, HCl 50 ml & Copper sulphate (CuSO4) 10 grams immersion or swab, etch for a few seconds) is shown in Fig.1.  Vol.9, No.8 Oxidation Studies of T-91 and T-22 Boiler Steels 751 The microstructure of T-91 steel revealed ferritic structure i.e. the white spot which is seen in microstructure is ferrite and the rest is other phase. After etching the T-22 sample revealed the microstructure which was found to consist of white ferrite and the rest is other phase. (a) Microstructure of T-91 steel (b) Microstructure of T-22 steel Fig. 1. Microstructure of T-91 & T-22 steel at 20x magnification. 2.3. Sample Preparation The experiment was performed on samples which were made to specified dimensions of approximately 20 x 15 x 3.5 mm from tubular sections. The specimens were polished on SiC emery paper down to the 1200 from 120 grades. Polishing was carried out on all six faces. The specimens were degreased (by ultrasonic cleaning in ethanol) and dried, then they were accurately weighed and measured to determine the total surface area exposed to the oxidative environment. 2.4. High Temperature Oxidation Study in Air Hot corrosion studies were conducted at 900°C in laboratory using silicon carbide tube furnace having PID temperature controller (make Digitech, India). The samples were subjected to mirror polishing which include cloth polishing which will provide uniformity of reaction while oxidation process. Then dimensions were accurately measured by digital venire (make Mototoyo, Japan) so as to calculate area which will be required for plotting of graph of weight gain per unit area verses number of cycle. Finally specimens were cleaned i.e. degreased by ethanol and kept in alumina boat. This alumina boat prior to performing of experiment was kept in oven for 5hr at 250°C in oven and then kept in furnace at 900°C for 2hr so that moisture is totally removed from boat. After this the sample was kept in boat and weight was taken initially and then slowly inserted in tubular furnace. Sample of T-91 and T-22 bare steel were kept in alumina boat and then inserted in different tubular furnace .These samples were kept in furnace for 1 hr at a temperature of 900°C and  752 Dinesh Gond, Vikas Chawla, D. Puri, S. Prakash Vol.9, No.8 then they were removed and cooled further for 20 minutes at room temperature and their weight were taken by electronic balance (make Contech, India) having sensitivity of 0.001 gms. Spalled scale was also taken into consideration which used to fall into the boat i.e. the weight was taken along with the boat. This cycle was repeated for 50 times i.e. 50 cycles were made for each sample. Corroded samples from air oxidation were analysed by XRD (BRUKER-binary V3) and SEM/EDAX and the oxide scale which fell into the boat were also analysed by XRD. Cu radiation was used in XRD at a step of 2°/min and the range of angle was 5-100°. 3. EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS 3.1. Behaviour in Air at Elevated Temperature The oxidation of sample which occurred in air at a temperature of 900°C is shown by plotting a graph in Fig. 2. On x-axis “number of cycles” and on y-axis “weight gain/area (mg/cm2)” was taken. The hot corrosion behaviour of T-91 in air was somewhat linear because the oxide layer formed on substrate got peeled off very easily and on the other hand T-22 boiler steels behaviour was parabolic. In spite of T-22 boiler steels paraboli c behaviou r the weig ht gain of T-91 steel was less because the oxide layer which were falling in boat were very thin in size. The graph reveals that T-91 steel is better than T-22 steel in an environment of air oxidation (for 50 cycles) Fig. 2. Weight gain plot for T-91 & T-22 bare steel exposed to cyclic study in air at 900°C for 50 cycles. Every line or curve in graph is having its approximate equation which is given below. For T-91 air oxidation the approximated curve is Y = -8.21659 + 6.17127 * X For T-22 air oxidation the approximated curve is 0 100 200 300 400 159 13172125293337414549 Weight gain/area (mg/cm 2 ) Number of cycle T91Airoxidised T22AirOxidised  Vol.9, No.8 Oxidation Studies of T-91 and T-22 Boiler Steels 753 Y = 3.22404 + 13.96049*X - 0.13266*X^2 (Where X is number of cycle and Y is weight gain/area & this equation is calculated by using analysis mode of Origin software) Extrusion of material from beneath and cracks in the scale were observed for the samples during hot corrosion runs and were more pronounced when T-22 steel was the substrate as is evident from Fig 3 and the oxide layer formed on T-22 sample is also thick as shown in Fig 8. (a) (b) Fig. 3. Macrograph of (a) T-91 air oxidised sample (b) T-22 air oxidised sample. 3.2. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis The samples after oxidation were removed from boat and their oxide scales which were separated from surface were also removed. Then they were analysed separately by XRD and after that only oxidised sample were analysed by SEM /EDA X. The results of XRD anal ysis contained graph indicating peak values (i.e. d values) which were used to identify various phases with the help of inorganic X-ray Diffraction data card fr om Powder diffrac tion file of JCPDS. Help of software named Philips X’pert High score and Eva was also taken for finding out compounds at respective peaks. 3.2.1. XRD result for T-91 and T-22 sample From the X-Ray Diffraction analysis it is found that ferrous oxide (Fe2O3), chromium ferr ous oxide (Cr, Fe)2O3 are mainly formed along with Cr2O3 in T-91 air oxidised sample and in T- 22 sample NiO is also formed in addition of Fe2O3 , (Cr, Fe)2O3, Cr2O3 (Fig. 4). Fe2O3, Cr2O3 form a protective oxide layer at surface due to which further oxidation is prevented as it acts as barrier for further corroding media to interact with substrate but as in case of T-22 steel, Nickel oxide (NiO) are formed which are not protective, rather than that NiO is said to be loose structured and thus lead to more pore size and thus results in more corrosion [17-19].  754 Dinesh Gond, Vikas Chawla, D. Puri, S. Prakash Vol.9, No.8 Fig. 4. XRD graph for T-91, T-22 sample and its oxide scales in air oxidised environment at 900°C. 3.3. Energy Dispersive X-ray (EDAX) Studies 3.3.1. Surface scale The SEM/EDAX analysis for T-91 & T-22 sample after oxidation in air for 50 cycles at 900°C is shown in Fig 5 and Fig 6. The oxide scale for T-91 air oxidised sample Fig 5(a & b) reveals the dominance of Fe2O3 and along with this compounds of Mo2O3 and Cr2O3 are also formed and at higher magnification the morphology indicates that the oxide formed is layer wise i.e. one below the other but the weight wise composition is approximately same. The SEM micrograph for corroded T-22 steel Fig 6 (a & b) indicate a scale with growth from inside having more amount of Mo2O3 as compare to other spots and the scale has got cracked from middle. Scale is mainly of Fe2O3 with little amount of Mo2O3, Cr2O3 and very small amount of NiO is also formed. As compared to T-91 steel, T-22 steel formed very little amount of chromium oxide which is mainly responsible for corrosion protection and in this some NiO oxide is also formed. As said before in description of XRD analysis, NiO is loose structured, hence there are two main reasons for less corrosion protection for T-22 steel; less amount of Cr2O3 formed and presence of NiO.  Vol.9, No.8 Oxidation Studies of T-91 and T-22 Boiler Steels 755 (a) T-91 air oxidised sample at scale of 500 µm (b) T-91 air oxidised sample at scale of 100µm Fig 5.Surface scale morphology and EDAX analysis (wt. %) for T-91 steel sample subjected to the cyclic oxidation at 900°C for 50 cycles in air environment. (a) T-22 air oxidised sample at scale of 500 µm (b) T-22 air oxidised sample at scale of 100µm Fig 6 .Surface scale morphology and EDAX analysis (wt. %) for T-22 steel sample subjected to the cyclic oxidation at 900°C for 50 cycles in air environment.  756 Dinesh Gond, Vikas Chawla, D. Puri, S. Prakash Vol.9, No.8 3.3.2. Cross-sectional scale Figure.7 shows the macrograph of cross section which were cut from samples. (a) (b) Fig. 7. Cross-sectional macrograph of (a) T-91 air oxidised sample (b) T-22 air oxidised sample In T-22 air oxidised sample Fig.8(b) at point 3 where the oxide layer has got separated from substrate shows decrease in elemental composition but at outer side i.e. at point 12 there is more ferrous oxide and at point 1 there is no oxygen but high amount of ferrous as it is substrate material. The BSEI micrograph shown in Fig. 8 reveals the condition of scale of T-91 and T-22 steel sample exposed to the cyclic oxidation for 50 cycles at 900°C. Elemental variation for corroded cross-section of T-91 and T-22 is also shown along with in form of point wise analysis. The EDAX analysis for T-91 air oxidised sample Fig 8(a) shows a very thin unusual oxide layer formed on surface. At very extreme end i.e. at point 8 all the elemental weight percentage goes down but at point 5 where there is little darkish phase ferrous oxide has formed along with small amount of molybdenum oxide. The nature of Fe and O is somewhat mirror type i.e. when Fe is more O is less and when Fe is less O is more, this is normally seen in all T-22 & T-91 cross-sectional analysis.  Vol.9, No.8 Oxidation Studies of T-91 and T-22 Boiler Steels 757 (a) T-91 air oxidised sample (b) T-22 air oxidised sample Fig.8. Oxide scale morphology and elemental composition variation across the cross section of T-91 and T-22 steel exposed to air at 900°C for 50 cycles. 4. DISCUSSION The results which were seen till now resemble th at corrosi on resistance property of T-91 steel is better than T-22 steel as weight gain of T-22 steel is more. Internal oxidation further led to the cracking of the scale due to the different thermal expansion coefficients of oxides in the scale from that of coating as suggested by P. Niranatlumpong [18]. As there are various elements and each have different thermal coe fficient of expansion hence there will be more stress generated which will lead to more cracking. Through these cracks, corrosive gases can penetrate to the base material and will thus allow significant grain boundary corrosion attack [20–22]. In spite of cracking, in some cases, little weight gain has been recorded. Extrusion of materials from beneath and oxide protrusions are believed to be due to the greater specific volume of oxides similar to the findings of N.S. Bornstein [23]. Comparatively higher weight gain values in case of T-22 steels might be attributed to the presence of molybdenum in this substrate steel. U.K. Chatterjee [24] has proposed that the cracking of the scale results from the enrichment by Mo at the substr ate scale interface, where MoO2 is formed. Substrate OxideSubstrate Oxide  758 Dinesh Gond, Vikas Chawla, D. Puri, S. Prakash Vol.9, No.8 Fig.9. BSEI and elemental X-ray mapping of the cross-section of T-91 sample exposed to cyclic hot corrosion in air at 900°C for 50 cycles. This oxide converts into MoO3 on further oxidation, which is in liquid form at the given temperature of exposure and penetrates along the alloy scale interface. MoO3 further reacts with Na2SO4 to form low melting point Na2MoO4 and SO3 gas contribute to further generation of cracks. The concentration of Mo at the interface will increase as the other alloying elements are oxidised and this MoO3 gets evaporated at the melt–gas interface [25]. The better corrosion resistance of T-91 steels may also be attributed to the absence of a NiO layer in the scale. During investigation, the NiO layer was observed in the oxide scale of T-22 steel. This layer has been suggested to be loose- structured by X. Wu [17], which may not be able to provide effective protection. P. Niranatlumpong [18] have also suggested increase in the pore size of Ni and Cr scale with increase in exposure time, which allows the degrading species to penetrate through the coating thereby resulting in the oxidation of substrate steels. O Cr Fe Mn Mo Substrate Oxide BSEI  Vol.9, No.8 Oxidation Studies of T-91 and T-22 Boiler Steels 759 Fig.10. BSEI and elemental X-ray mapping of the cross-section of T-22 sample exposed to cyclic hot corrosion in air at 900°C for 50 cycles. BSEI Substrate Oxide Cr Fe Mn Mo Ni O  760 Dinesh Gond, Vikas Chawla, D. Puri, S. Prakash Vol.9, No.8 5. CONCLUSION The cyclic oxidation of this T-91 steel in air follow linear rate of weight gain but in case of T- 91 the weight gain (0.935 gms) was much less as compared to T-22 steel (1.342 gms) which shows parabolic nature because T-91 steel has formed hematite (Fe2O3) at top surface while T-22 steel has formed nickel oxide (NiO) which is said to be loose structured and not able to provide effective protection. It also increases the pore size of Ni and Cr scale, which allows the degrading species to penetrate through the coating thereby resulting in the oxidation of substrate [17-19]. Hence T-91 is found to be superior to T-22 steel and as per the cross section morphology the scale thickness of T-91 is very small as compared to T-22 steel. REFERENCES [1] J.C. Van Wortel, C.F. Etienne, F. Arav, Application of modified 9chromium steels in power generation components, in: VDEh ECSC Information Day, The Manufacture and Properties of Steel 91 for the Power Plant and Process Industries, Dusseldorf, 5th November, 1992, paper 4.2. [2] T. Fujita, Current progress in advanced high Cr steel for high temperature applications ISIJ Int. 32 (2) (1992) p.175. [3] J. Orr, A. Di Gianfrancesco, The effect of compositional variations on the properties of steel 91, in:VDEh ECSC Information Day, The Manufacture and Properties of Steel 91 for the Power Plant and Process Industries, Dusseldorf, 5th November, 1992, paper 2.4. [4] ASTM, Standard specification for seamless ferritic and austenitic alloy-steel boiler, superheater and heat-exchanger tubes, A 213/A 213M-90a, 1990. [5] ASTM, Standard specification for seamless ferritic alloy-steel pipe for high- temperature service, A 335/A 335M-95a, 1996. [6] R. Panton-Kent, Phase balance in 9%Cr1%Mo steel welds. TWI report, Bulletin 1, January/February 1991, p.15. [7] G.E. Birchenall, A brief history of the study of oxidation of metals and alloys, in: High Temperature Corrosion, Proceedings, NACE, San Diego, CA, 1981, p.3. [8] D.A. Jones, Principles and Prevention of Corrosion, second ed., Prentice Hall, USA, 1996. [9] P. Kofstad, High-temperature Corrosion, Elsevier Applied Science, London, 1988, pp. 382–385 (Chapter 11). [10] I. Saeki, T. Saito, R. Furuichi, M. Itoh, Growth process of protective oxides formed on type 304 and 430 stainless steels at 1273°K, Corros. Sci. 40 (8) (1998) p.1295. [11] S. Jianian, Z. Longjiang, L. Tiefan, High temperature oxidation of Fe–Cr alloys in wet oxygen, Oxid. Met. 48 (3, 4) (1997) p.347. [12] Z. Tokei, H. Viefhaus, H.J. Grabke, Initial stages of oxidation of a 9CrMoV steel: role of segregation and martensite laths, Appl. Surf. Sci. 165 (1) (2000) p. 23. [13] A.P. Greeff, C.W. Louw, H.C. Swart, The oxidation of industrial Fe CrM o ste el, Corros. Sci. 42 (10) (2000) p.1725.  Vol.9, No.8 Oxidation Studies of T-91 and T-22 Boiler Steels 761 [14] A. Arztegui, T. Gomez-Acebo, F. Castro, Steam oxidation of ferritic steels: kinetics and microstructure, Bol. Soc. Esp. Ceram. Vidr. 39 (3) (2000). p. 305. [15] A.S. Khanna, P. Rodriguez, J.B. Gananamoorthy, Oxidation kinetics, breakaway oxidation, and inversion phenomenon in 9Cr–1Mo steels, Oxid. Met. 26 (3, 4) (1986) p.171. [16] Dionisio Laverde, Tomas Gomez-Acebo ,Francisco Castro, Continuous and cyclic oxidation of T-91 ferritic steel under steam, Corrosion Science 46 ,2 July 2003, pp.613–631. [17] X. Wu, D. Weng, Z. Chen, L. Xu, Surface Coating Technology, 140 (2001), p.231. [18] P. Niranatlumpong, C.B. Ponton, H.E. Evans, Oxid. Met, 53 (3–4) (2000), pp. 241-258. [19] Buta Singh Sidhu, S. Prakash , Performance of NiCrAlY, Ni–Cr, Stellite-6 and Ni3Al coatings in Na2SO4–60% V2O5 environment at 900°C under cyclic conditions, Surface & Coatings Technology 201,17 April 2006, pp.1643–1654. [20] S. Danyluk, J.Y. Park, Corrosion 35 (12) (1979) p.575. [21] D. Wang, Surf. Coat. Technol. 36 (1988) p.49. [22] S.E. Sadique, A.H. Mollah, M.S. Islam, M.M. Ali, M.H.H. Megat, S.Basri, Oxid. Met. 54 (5–6) (2000) p.385. [23] N.S. Bornstein, M.A. Decrescente, H.A. Roth, Proc. of Conf. on Gas Turbine Mater in the Marine Environment, MMIC-75-27, Columbus,Ohio, USA, 1975, p. 115. [24] U.K. Chatterjee, S.K. Bose, S.K. Roy, Environmental Degradation of Metals, Marcel Dekker, New York, 2001. [25] A.K. Misra, J. Electrochem. Soc. 133 (5) (1986) p.1029. |