Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

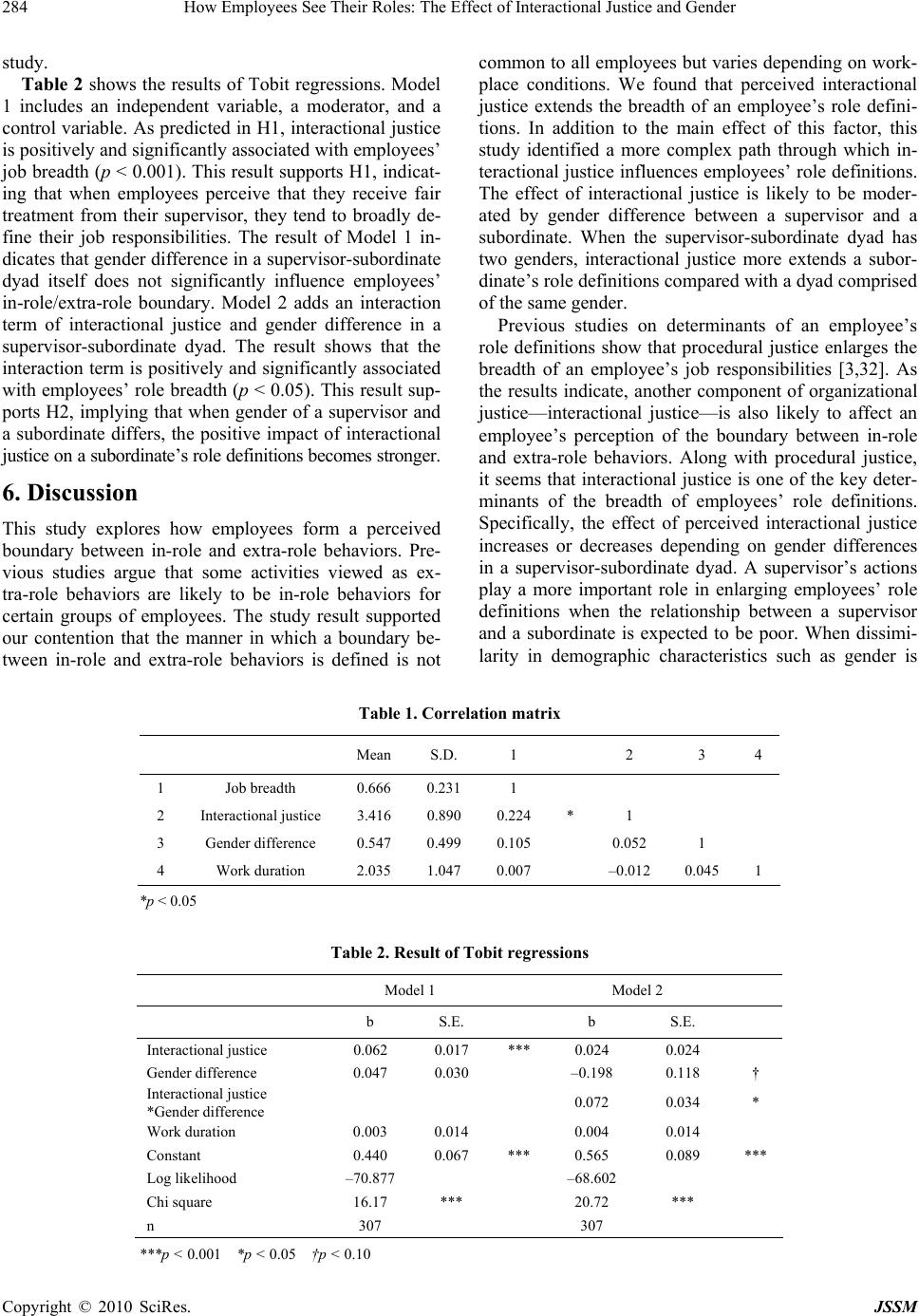

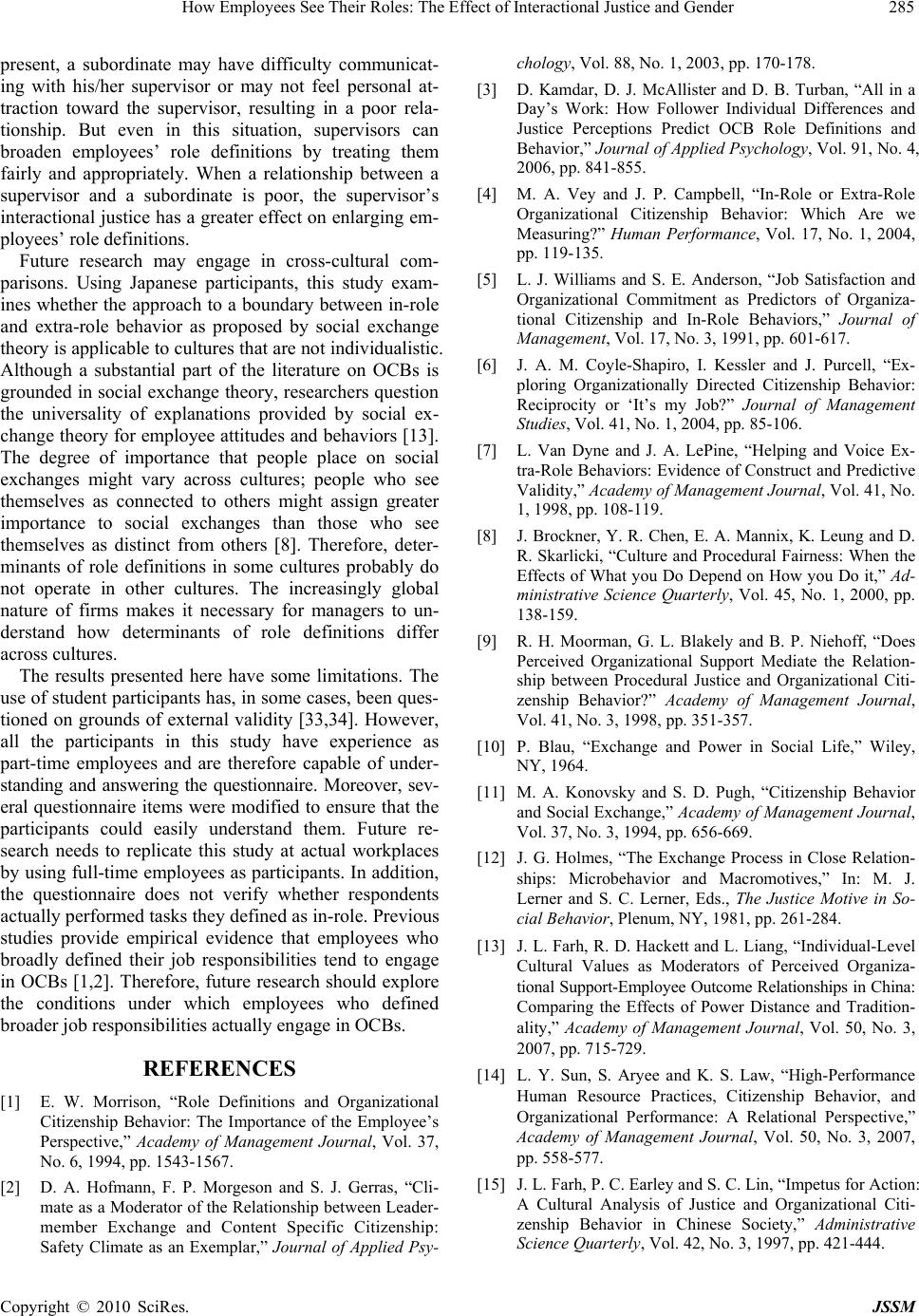

J. Service Science & Management, 2010, 3, 281-286 doi:10.4236/jssm.2010.32034 Published Online June 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jssm) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSSM How Employees See Their Roles: The Effect of Interactional Justice and Gender Naoki Ando1, Satoshi Matsuda2 1Faculty of Business Administration, Hosei University, Tokyo, Japan; 2Faculty of Foreign Studies, The University of Kitakyusyu, Kitakyusyu, Japan. Email: nando@hosei.ac.jp, sato6@kitakyu-u.ac.jp Received January 18th, 2010; revised February 20th, 2010; accepted April 2nd, 2010. ABSTRACT This study examines whether the perceived boundary between in-role and extra-role behaviors varies depending on workplace conditions, emphasizing how interactional justice influences an employee’s role definitions. We collect data through a questionnaire survey and adopt Tobit regressions for hypothesis testing. The study results indicate that per- ceived interactional justice enlarges the breadth of an employee’s role definitions. In addition, the positive impact of interactional justice on an employee’s role definition is strong when a supervisor-subordinate dyad comprises different genders. Keywords: Organizational Citizenship Behavior, Role Definition, Interactional Justice, Gender 1. Introduction Human resource management is especially important for developing and sustaining competitive advantages in un- certain and volatile environments. Firms seeking to im- prove their efficiency and effectiveness need employees who are willing to exceed their formal job requirements [1]. An argument leads to the research stream of organ- izational citizenship behaviors (OCBs). In the growing body of research on OCBs, researchers assume that every dimension of OCB is an extra-role behavior for all em- ployees and that the boundary between extra-role and in-role behaviors does not depend on workplace condi- tions. However, some studies question whether or not a clear conceptual boundary exists between extra-role and in-role behaviors [1]. In response to this criticism, other researchers have examined whether a clear boundary between extra-role and in-role behaviors really exists or whether the boundary varies across employees [2-4]. They found evidence that a boundary between in-role and extra-role behaviors varies depending on workplace conditions and that extra-role behaviors and OCBs are distinctive constructs [4,5]. In line with the argument that a boundary between in-role and extra-role behaviors is not stable, this study contributes to the literature on OCBs through investigat- ing determinants of employees’ role definitions, empha- sizing how interactional justice affects employees’ per- ceptions of in-role/extra-role behaviors. We also examine how the gender difference in a supervisor-subordinate dyad works as a moderator of the relationship between interactional justice and employees’ role definitions. Previous studies found that procedural justice has a posi- tive effect on the breadth of employees’ role definitions [3,6]. In comparison, the path through which interac- tional justice influences the breadth of employees’ role definitions has not received much attention from re- searchers. Thus, this study aims to explore a path through which interactional justice influences employees’ role definitions. By providing evidence that employees’ defi- nitions of their in-role behaviors are influenced by work- place conditions, this study contributes to the literature on OCBs. The following sections briefly review the literature on the role definitions and then present hypotheses regard- ing factors that affect the breadth of role definitions. The subsequent sections explain the analytical method and present the results, concluding with implications of this study and suggestions for future research. 2. Literature Review Previous studies assume that OCBs are extra-role behav- iors for all employees. Extra-role behaviors are neither specified in advance by role prescriptions nor sources of punitive consequences when not performed [7]. Re- searchers assume that every employee differentiates in-role from extra-role behaviors in the same manner and  How Employees See Their Roles: The Effect of Interactional Justice and Gender 282 performs OCBs as extra-role behaviors. But recent stud- ies report that a perceived boundary between in-role and extra-role behaviors can vary not only from one em- ployee to another but also between employees and super- visors [1,3,6]. For example, Morrison (1994) finds varia- tions in job definitions not only among employees but also between employees and supervisors [1]. Further, she observes that job satisfaction as well as emotional at- tachment and a sense of loyalty to an organization serve to enlarge employees’ job definitions. Her results indi- cate that when employees define their jobs broadly, they are more likely to engage in behaviors that many studies consider as extra-role [1]. Similarly, Coyle-Shapiro et al. (2004) confirm that employees who define their job re- sponsibilities broadly are more likely to engage in OCBs [6]. They also find that perceived procedural justice af- fects mutual commitment, which in turn, influences em- ployee-defined job breadth. Kamdar et al. (2006) exam- ine the moderating effect of employees’ personality on the relationship between procedural justice and role defi- nitions, finding that employees tend to define their jobs broadly when they perceive procedural justice [3]. Indi- vidual differences in personality expand or contract their role definitions. The authors further show that reciproca- tion wariness and perspective-taking moderate the rela- tionship between procedural justice and role definitions. Similarly to Morrison (1994) and Coyle-Shapiro et al. (2004), Kamdar et al. (2006) observe that job breadth positively affects employees’ OCBs and that employees’ perception of procedural justice influences their OCBs more strongly when their role definitions are narrow rather than broad. These studies suggest that job definitions vary among employees and the boundary between in-role and ex- tra-role behaviors is neither clearly defined nor stable [1]. Employees may engage in behaviors that the literature views as extra-role because they consider them to be in-role [1,2]. In that case, identifying an employee’s boundary between in-role and extra-role behaviors is essential, along with enlarging an employee’s role defini- tions to elicit OCBs and improve organizational effi- ciency and effectiveness. However, frameworks for un- derstanding factors that affect the breadth of role defini- tions are yet to be substantially explored [3]. Researchers need to investigate how employees themselves define the breadth of their job responsibilities [1]. 3. Hypotheses The OCB literature proposes social exchange theory as theoretical ground to explain employees’ OCBs [8,9]. Social exchange generates an expectation of some future return for contributions, as in the case of economic ex- change; however, unlike an economic exchange, the ex- act nature of the return is unspecified in social exchange [10,11]. While economic exchange occurs on a quid pro quo basis, social exchange is based on an individual’s belief that the other party to the exchange will fairly dis- charge its obligations in the long run [11,12]. Social ex- change also emphasizes the norms of reciprocity where the inducement that a party provides engenders a sense of obligation on the part of the other party [13]. This prompts reciprocal behaviors that help the first party attain his goals and the reciprocation maintains and sustains the exchange relationship [10,14]. The literature argues that organizational justice is a key determinant of employees’ OCBs [11,15,16]. Justice theory contends that employees’ work attitudes and be- haviors depend on the perceived justice of an organiza- tion’s procedures or a supervisor’s treatment [8,17,18]. While procedural justice pertains to the processes that lead to decision outcomes [19,20], interactional justice concerns how an individual is treated while a procedure is being carried out [19,21-23]. When employees think they are being treated fairly by their supervisors, they believe that the supervisor values and respects them as an organizational member and cares about their well-being [9,18,23]. They then seek to maintain a cordial relation- ship with the supervisor or the organization itself and feel obliged to reciprocate in some fashion. They may recip- rocate the supervisor or the organization with greater productivity and higher morale [8]. An alternative man- ner to reciprocate the supervisor’s fairness might be for employees to expand their role definitions beyond the normal requirements [2]. Previous studies showed that interactional justice is positively related to employees’ OCBs [16]. Employees may engage in OCBs as a result of their extended definition of in-role behaviors. These arguments lead to the prediction that employees extend their role definitions when they receive fair treatment from their supervisors. Accordingly, we hypothesize: Hypothesis 1: Interactional justice is positively asso- ciated with the breadth of an employee’s role definitions. Gender role theory suggests that employees in an or- ganization are embedded in culturally rooted expecta- tions about their gender role [24,25]. Gender may affect employees’ perception of what they should do in an or- ganization. External social pressure favors behavior con- sistent with culturally prescribed gender roles [24,25]. To obtain legitimacy in an organization embedded in social pressure, employees may define their in-role behavior in line with culturally- and socially-expected gender role. This argument suggests that when a gender difference exists between a supervisor and a subordinate, the super- visor’s expectation of the subordinate’s job definition might be different from the subordinate’s. The inconsis- tent expectation of job responsibilities may negatively affect the relationship between a supervisor and a subor- dinate [26]. In addition, demographic similarity in a su- pervisor-subordinate dyad relates to cognitive similarity [26,27]. This suggests that a supervisor-subordinate dyad Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSSM  How Employees See Their Roles: The Effect of Interactional Justice and Gender283 of the same sex creates a common frame of reference, resulting in increased interpersonal attraction and com- munication [26]. Thus, same sex supervisor-subordinate dyads could enhance the quality of the relationship com- pared with different sex dyads. When employees have a good relationship with their supervisors, they may want to extend their role defini- tions beyond the requirements formally assigned by their supervisor as an expression of positive feeling, regardless of their supervisor’s fair treatment. Their role definitions will depend less on the supervisor’s fair treatment when a subordinate and a supervisor are the same gender. In contrast, when the relationship between a supervisor and a subordinate is poor due to the difference in gender, the subordinate’s role definitions may be narrower. In this case, the supervisor’s actions may have a greater influ- ence on the subordinate’s decisions on the breadth of role definitions. Therefore, we hypothesize: Hypothesis 2: The positive relationship between inter- actional justice and the breadth of an employee’s role definitions is stronger when the supervisor and subordi- nate are different genders. 4. Method 4.1 Data Collection Participants in this study are undergraduate students at two public universities in Western Japan. We use a ques- tionnaire to collect the data for hypothesis testing which participants completed during class. All the questions refer to the participants’ current part-time jobs. Those without part-time jobs are excluded. Three hundred and seven undergraduate students participated in this study. The participants’ average age is 20.7 (s.d. = 2.6) and they have been at their current jobs 11.7 months (s.d. = 10.5). Among the participants, 118 are male and 189 are female. T-tests are conducted for several items to examine whether a significant difference exists between the two universi- ties; no significant differences were found between the two groups of participants. The questionnaire was developed based on a literature review of related work. To ensure content validity, meas- urements used in previous studies were adopted and re- vised where necessary. The questionnaire was written first in English and then translated into Japanese. To en- sure construct equivalence and data comparability, a back-translation procedure was conducted. Pilot studies were carried out at the two universities, which formed the basis for modifying the wording of the questionnaire. 4.2 Measures The dependent variable of this study is the breadth of an employee’s role definitions. This variable was operation- alized using the seven items developed by Pearce and Gregersen (1991) to measure extra-role behavior [28]. Their tool consisted of 10 items but since the participants in our study are undergraduates with part-time jobs, only seven items were used. The other three items are related with tasks not usually required for part-time employees. Following Coyle-Shapiro et al. (2004), we asked partici- pants to classify the seven items into two categories [6]: 1) I feel this is part of my work duty and 2) I feel this is something extra. A proxy for the breadth of role defini- tions are calculated as a ratio of items classified as 1) to the total items. The independent variable of interest is interactional justice—the way an employee is treated during a proce- dure [19,21-23]. Interactional justice pertains to whether supervisors responsible for making a decision treat their subordinates with respect and dignity [19,21,29]. In this research, interactional justice is measured by using a six-item scale adopted from Moorman (1991) [16]. A five-point Likert scale that ranges from “strongly dis- agree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5) was used. Gender difference in a supervisor-subordinate dyad is a moderator in this study. Participants reported their gender and their supervisor’s in the questionnaire. Dif- ferent sex supervisor-subordinate dyads are coded one and same sex dyads are coded zero. In addition to the independent variable and the mod- erator, we control for participants’ length of work at their current part-time jobs. The log of work duration are cal- culated and used for this study. Gender of participants is not controlled for because it is highly correlated with the dummy variable that represents gender difference in a supervisor-subordinate dyad. 5. Results Table 1 shows descriptive statistics and a correlation matrix. Correlation coefficients in Table 1 are low over- all. It does not appear that any severe problem of multi- collinearity is present. To further detect potential multi- collinearity problem, variance inflation factors (VIF) are calculated. All VIF scores are much less than 10. Cron- bach’s alpha for interactional justice shows an acceptable level of internal consistency [30]. To check for common method variance derived from the same source in col- lecting all the data, Harman’s one-factor test is conducted, whereby all the items in the questionnaire are included in factor analysis. The result shows that neither a single factor nor a general factor accounts for the majority of the covariance of the variables. This result indicates the absence of a severe common method variance problem. A Tobit model is used to test the hypotheses because the dependent variable is a proportion. A Tobit model is preferred to an ordinary least squares regression (OLS) analysis when a dependent variable is censored at some value on the left- and/or right side; OLS can lead to bi- ased coefficient estimates in such a case [31]. A dou- ble-censored Tobit model is employed for this empirical Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSSM  How Employees See Their Roles: The Effect of Interactional Justice and Gender Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSSM 284 study. Table 2 shows the results of Tobit regressions. Model 1 includes an independent variable, a moderator, and a control variable. As predicted in H1, interactional justice is positively and significantly associated with employees’ job breadth (p < 0.001). This result supports H1, indicat- ing that when employees perceive that they receive fair treatment from their supervisor, they tend to broadly de- fine their job responsibilities. The result of Model 1 in- dicates that gender difference in a supervisor-subordinate dyad itself does not significantly influence employees’ in-role/extra-role boundary. Model 2 adds an interaction term of interactional justice and gender difference in a supervisor-subordinate dyad. The result shows that the interaction term is positively and significantly associated with employees’ role breadth (p < 0.05). This result sup- ports H2, implying that when gender of a supervisor and a subordinate differs, the positive impact of interactional justice on a subordinate’s role definitions becomes stronger. 6. Discussion This study explores how employees form a perceived boundary between in-role and extra-role behaviors. Pre- vious studies argue that some activities viewed as ex- tra-role behaviors are likely to be in-role behaviors for certain groups of employees. The study result supported our contention that the manner in which a boundary be- tween in-role and extra-role behaviors is defined is not common to all employees but varies depending on work- place conditions. We found that perceived interactional justice extends the breadth of an employee’s role defini- tions. In addition to the main effect of this factor, this study identified a more complex path through which in- teractional justice influences employees’ role definitions. The effect of interactional justice is likely to be moder- ated by gender difference between a supervisor and a subordinate. When the supervisor-subordinate dyad has two genders, interactional justice more extends a subor- dinate’s role definitions compared with a dyad comprised of the same gender. Previous studies on determinants of an employee’s role definitions show that procedural justice enlarges the breadth of an employee’s job responsibilities [3,32]. As the results indicate, another component of organizational justice—interactional justice—is also likely to affect an employee’s perception of the boundary between in-role and extra-role behaviors. Along with procedural justice, it seems that interactional justice is one of the key deter- minants of the breadth of employees’ role definitions. Specifically, the effect of perceived interactional justice increases or decreases depending on gender differences in a supervisor-subordinate dyad. A supervisor’s actions play a more important role in enlarging employees’ role definitions when the relationship between a supervisor and a subordinate is expected to be poor. When dissimi- larity in demographic characteristics such as gender is Table 1. Correlation matrix Mean S.D. 1 2 3 4 1 Job breadth 0.666 0.231 1 2 Interactional justice 3.416 0.890 0.224 * 1 3 Gender difference 0.547 0.499 0.105 0.052 1 4 Work duration 2.035 1.047 0.007 –0.012 0.045 1 *p < 0.05 Table 2. Result of Tobit regressions Model 1 Model 2 b S.E. b S.E. Interactional justice 0.062 0.017 *** 0.024 0.024 Gender difference 0.047 0.030 –0.198 0.118 † Interactional justice *Gender difference 0.072 0.034 * Work duration 0.003 0.014 0.004 0.014 Constant 0.440 0.067 *** 0.565 0.089 *** Log likelihood –70.877 –68.602 Chi square 16.17 *** 20.72 *** n 307 307 ***p < 0.001 *p < 0.05 †p < 0.10  How Employees See Their Roles: The Effect of Interactional Justice and Gender285 present, a subordinate may have difficulty communicat- ing with his/her supervisor or may not feel personal at- traction toward the supervisor, resulting in a poor rela- tionship. But even in this situation, supervisors can broaden employees’ role definitions by treating them fairly and appropriately. When a relationship between a supervisor and a subordinate is poor, the supervisor’s interactional justice has a greater effect on enlarging em- ployees’ role definitions. Future research may engage in cross-cultural com- parisons. Using Japanese participants, this study exam- ines whether the approach to a boundary between in-role and extra-role behavior as proposed by social exchange theory is applicable to cultures that are not individualistic. Although a substantial part of the literature on OCBs is grounded in social exchange theory, researchers question the universality of explanations provided by social ex- change theory for employee attitudes and behaviors [13]. The degree of importance that people place on social exchanges might vary across cultures; people who see themselves as connected to others might assign greater importance to social exchanges than those who see themselves as distinct from others [8]. Therefore, deter- minants of role definitions in some cultures probably do not operate in other cultures. The increasingly global nature of firms makes it necessary for managers to un- derstand how determinants of role definitions differ across cultures. The results presented here have some limitations. The use of student participants has, in some cases, been ques- tioned on grounds of external validity [33,34]. However, all the participants in this study have experience as part-time employees and are therefore capable of under- standing and answering the questionnaire. Moreover, sev- eral questionnaire items were modified to ensure that the participants could easily understand them. Future re- search needs to replicate this study at actual workplaces by using full-time employees as participants. In addition, the questionnaire does not verify whether respondents actually performed tasks they defined as in-role. Previous studies provide empirical evidence that employees who broadly defined their job responsibilities tend to engage in OCBs [1,2]. Therefore, future research should explore the conditions under which employees who defined broader job responsibilities actually engage in OCBs. REFERENCES [1] E. W. Morrison, “Role Definitions and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Importance of the Employee’s Perspective,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 37, No. 6, 1994, pp. 1543-1567. [2] D. A. Hofmann, F. P. Morgeson and S. J. Gerras, “Cli- mate as a Moderator of the Relationship between Leader- member Exchange and Content Specific Citizenship: Safety Climate as an Exemplar,” Journal of Applied Psy- chology, Vol. 88, No. 1, 2003, pp. 170-178. [3] D. Kamdar, D. J. McAllister and D. B. Turban, “All in a Day’s Work: How Follower Individual Differences and Justice Perceptions Predict OCB Role Definitions and Behavior,” Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 91, No. 4, 2006, pp. 841-855. [4] M. A. Vey and J. P. Campbell, “In-Role or Extra-Role Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Which Are we Measuring?” Human Performance, Vol. 17, No. 1, 2004, pp. 119-135. [5] L. J. Williams and S. E. Anderson, “Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment as Predictors of Organiza- tional Citizenship and In-Role Behaviors,” Journal of Management, Vol. 17, No. 3, 1991, pp. 601-617. [6] J. A. M. Coyle-Shapiro, I. Kessler and J. Purcell, “Ex- ploring Organizationally Directed Citizenship Behavior: Reciprocity or ‘It’s my Job?” Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 41, No. 1, 2004, pp. 85-106. [7] L. Van Dyne and J. A. LePine, “Helping and Voice Ex- tra-Role Behaviors: Evidence of Construct and Predictive Validity,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 41, No. 1, 1998, pp. 108-119. [8] J. Brockner, Y. R. Chen, E. A. Mannix, K. Leung and D. R. Skarlicki, “Culture and Procedural Fairness: When the Effects of What you Do Depend on How you Do it,” Ad- ministrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 45, No. 1, 2000, pp. 138-159. [9] R. H. Moorman, G. L. Blakely and B. P. Niehoff, “Does Perceived Organizational Support Mediate the Relation- ship between Procedural Justice and Organizational Citi- zenship Behavior?” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 41, No. 3, 1998, pp. 351-357. [10] P. Blau, “Exchange and Power in Social Life,” Wiley, NY, 1964. [11] M. A. Konovsky and S. D. Pugh, “Citizenship Behavior and Social Exchange,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 37, No. 3, 1994, pp. 656-669. [12] J. G. Holmes, “The Exchange Process in Close Relation- ships: Microbehavior and Macromotives,” In: M. J. Lerner and S. C. Lerner, Eds., The Justice Motive in So- cial Behavior, Plenum, NY, 1981, pp. 261-284. [13] J. L. Farh, R. D. Hackett and L. Liang, “Individual-Level Cultural Values as Moderators of Perceived Organiza- tional Support-Employee Outcome Relationships in China: Comparing the Effects of Power Distance and Tradition- ality,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 50, No. 3, 2007, pp. 715-729. [14] L. Y. Sun, S. Aryee and K. S. Law, “High-Performance Human Resource Practices, Citizenship Behavior, and Organizational Performance: A Relational Perspective,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 50, No. 3, 2007, pp. 558-577. [15] J. L. Farh, P. C. Earley and S. C. Lin, “Impetus for Action: A Cultural Analysis of Justice and Organizational Citi- zenship Behavior in Chinese Society,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 42, No. 3, 1997, pp. 421-444. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSSM  How Employees See Their Roles: The Effect of Interactional Justice and Gender 286 [16] R. H. Moorman, “Relationship between Organizational Justice and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: Do Fair- ness Perceptions Influence Employee Citizenship?” Jour- nal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 76, No. 6, 1991, pp. 845-855. [17] R. Folger and M. A. Konovsky, “Effects of Procedural and Distributive Justice on Reactions to Pay Raise Deci- sions,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 32, No. 1, 1989, pp. 115-130. [18] E. A. Lind and T. R. Tyler, “The Social Psychology of Procedural Justice,” Plenum, NY, 1988. [19] J. Kickul, L. K. Gundry and M. Posig, “Does Trust Mat- ter? The Relationship between Equity Sensitivity and Per- ceived Organizational Justice,” Journal of Business Eth- ics, Vol. 56, No. 3, 2005, pp. 205-218. [20] R. Pillai, T. A. Scandura and E. A. Williams, “Leadership and Organizational Justice: Similarities and Differences across Cultures,” Journal of International Business Stud- ies, Vol. 30, No. 4, 1999, pp. 763-779. [21] R. J. Bies and J. S. Moag, “Interactional Justice: Commu- nication Criteria of Fairness,” Research on Negotiation in Organization, Vol. 1, 1986, pp. 43-55. [22] S. S. Masterson, K. Lewis, B. M. Goldman and M. S. Taylor, “Integrating Justice and Social Exchange: The Differing Effects of Fair Procedures and Treatment on Work Relationships,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 43, No. 4, 2000, pp. 738-748. [23] B. P. Niehoff and R. H. Moorman, “Justice as a Mediator of the Relationship between Methods of Monitoring and Organizational Citizenship Behavior,” Academy of Man- agement Journal, Vol. 36, No. 3, 1993, pp. 527-556. [24] D. L. Kidder, “The Influence of Gender on the Perform- ance of Organizational Citizenship Behaviors,” Journal of Management, Vol. 28, No. 5, 2002, pp. 629-648. [25] A. Eagly, S. J. Karau and M. G. Makajhani, “Gender and the Effectiveness of Leaders: A Meta-Analysis,” Psycho- logical Bulletin, Vol. 117, No. 1, 1995, pp. 125-145. [26] M. M. Suazo, W. H. Turnley and R. R. Mai-Dalton, “Characteristics of the Supervisor-Subordinate Relation- ship as Predictors of Psychological Contract Breach,” Journal of Managerial Issues, Vol. 20, No. 3, 2008, pp. 295-312. [27] C. W. Allinson, S. J. Armstrong and J. Hayes, “The Ef- fects of Cognitive Style on Leader-Member Exchange: A Study of Manager-Subordinate Dyads,” Journal of Oc- cupational and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 74, No. 2, 2001, pp. 201-220. [28] J. L. Pearce and H. B. Gregersen, “Task Interdependence and Extrarole Behavior: A Test of the Mediating Effects of Felt Responsibility,” Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 76, No. 6, 1991, pp. 838-844. [29] D. L. Shapiro, E. H. Buttner and B. Barry, “Explanations: What Factors Enhance their Perceived Adequacy?” Or- ganizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 58, No. 3, 1994, pp. 346-368. [30] J. Nunnally, “Psychometric Theory,” 2nd Edition, McGraw- Hill, NY, 1978. [31] A. Delios and W. J. Henisz, “Japanese Firms’ Investment Strategies in Emerging Economies,” Academy of Man- agement Journal, Vol. 43, No. 3, 2000, pp. 305-323. [32] B. J. Tepper, D. Lockhart and J. Hoobler, “Justice, Citi- zenship, and Role Definition Effects,” Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 86, No. 4, 2001, pp. 789-796. [33] M. E. Gordon, L. A. Slade and N. Schmitt, “The ‘Science of the Sophomore’ Revisited: From Conjecture to Em- piricism,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 11, No. 1, 1986, pp. 191-207. [34] D. H. McKnight, V. Choudhury and C. Kacmar, “Devel- oping and Validating Trust Measures for E-Commerce: An Integrative Typology,” Information Systems Research, Vol. 13, No. 3, 2002, pp. 334-359. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSSM |