Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

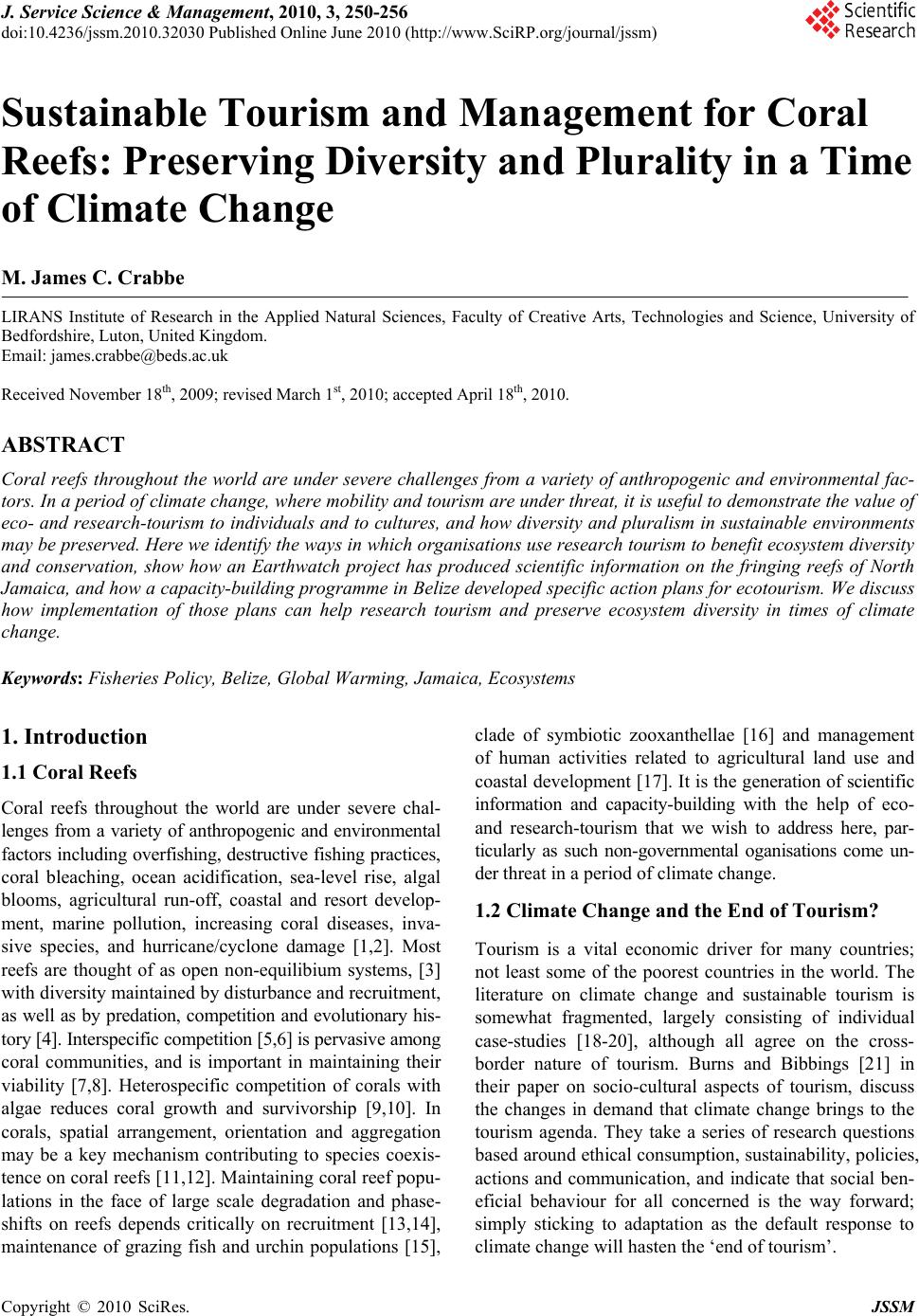

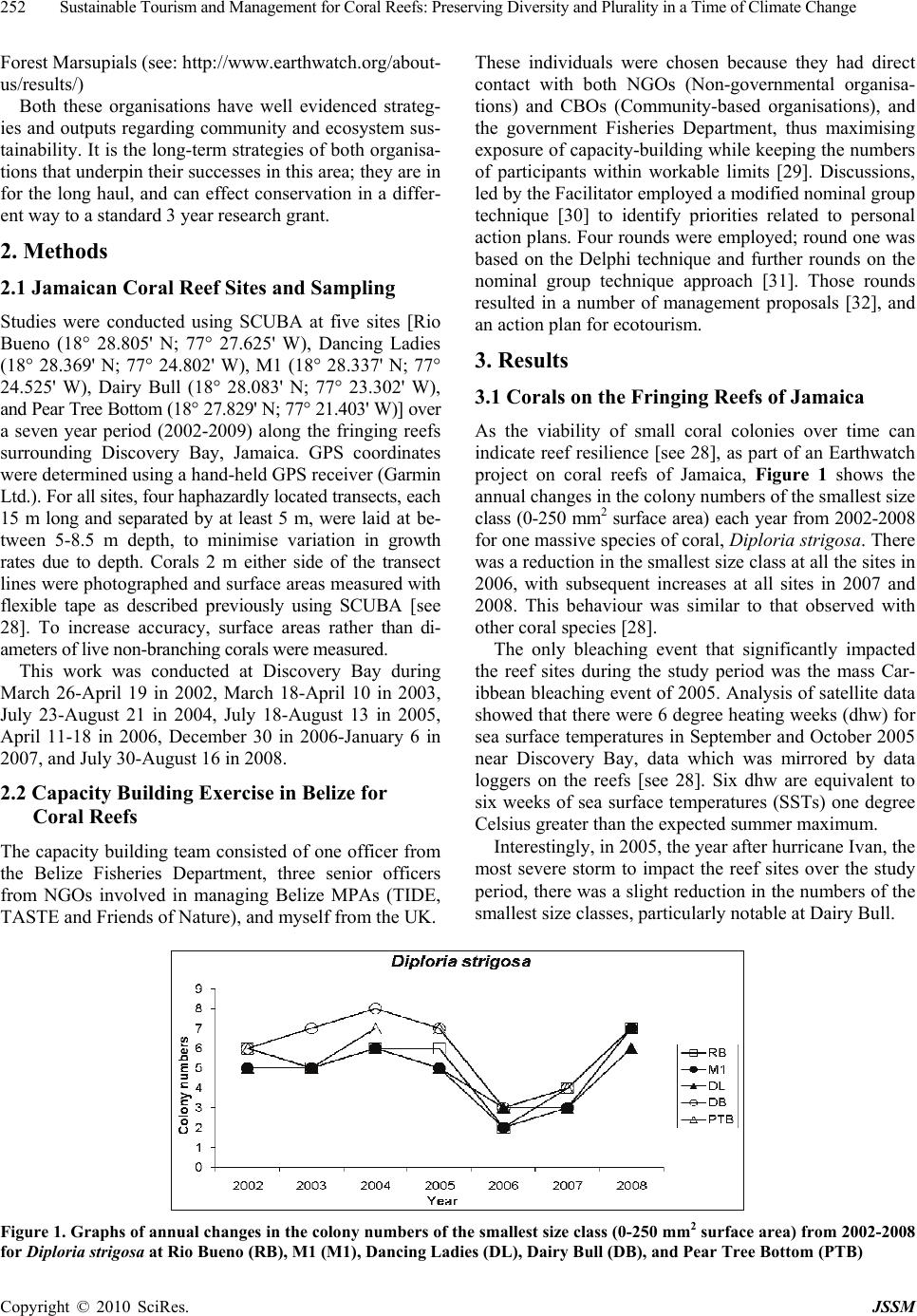

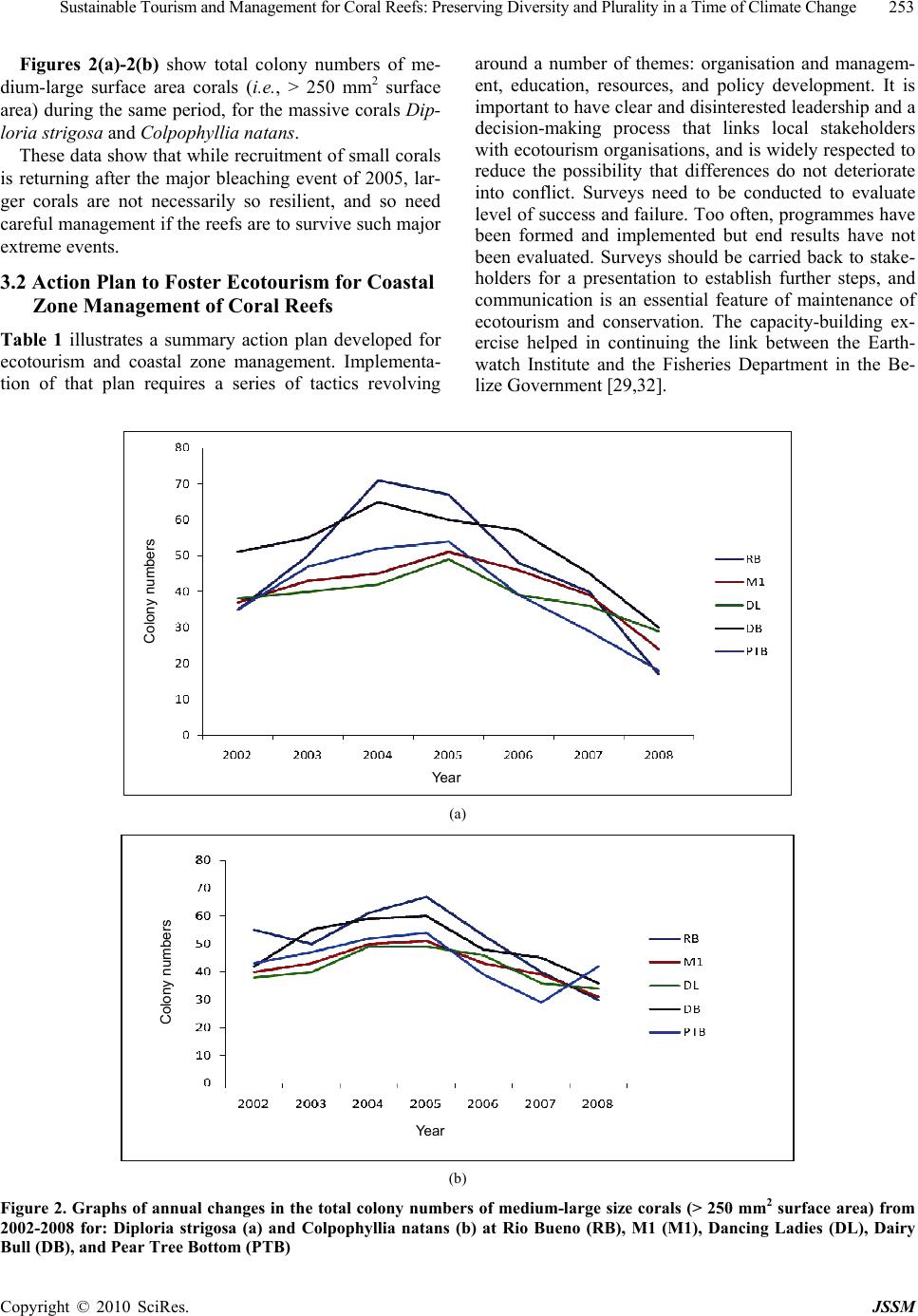

J. Service Science & Management, 2010, 3, 250-256 doi:10.4236/jssm.2010.32030 Published Online June 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jssm) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSSM Sustainable Tourism and Management for Coral Reefs: Preserving Diversity and Plurality in a Time of Climate Change M. James C. Crabbe LIRANS Institute of Research in the Applied Natural Sciences, Faculty of Creative Arts, Technologies and Science, University of Bedfordshire, Luton, United Kingdom. Email: james.crabbe@beds.ac.uk Received November 18th, 2009; revised March 1st, 2010; accepted April 18th, 2010. ABSTRACT Coral reefs throughout the world are under severe challenges from a variety of anthropogenic and environmental fac- tors. In a period of climate change, where mobility and tourism are under threat, it is useful to demonstrate the value of eco- and research-tourism to individuals and to cultures, and how diversity and pluralism in sustainable environments may be preserved. Here we identify the ways in which organisations use research tourism to benefit ecosystem diversity and conservation, show how an Earthwatch project has produced scientific information on the fringing reefs of North Jamaica, and how a capacity-building programme in Belize developed specific action plans for ecotourism. We discuss how implementation of those plans can help research tourism and preserve ecosystem diversity in times of climate change. Keywords: Fisheries Policy, Belize, Global Warming, Jamaica, Ecosystems 1. Introduction 1.1 Coral Reefs Coral reefs throughout the world are under severe chal- lenges from a variety of anthropogenic and environmental factors including overfishing, destructive fishing practices, coral bleaching, ocean acidification, sea-level rise, algal blooms, agricultural run-off, coastal and resort develop- ment, marine pollution, increasing coral diseases, inva- sive species, and hurricane/cyclone damage [1,2]. Most reefs are thought of as open non-equilibium systems, [3] with diversity maintained by disturbance and recruitment, as well as by predation, competition and evolutionary his- tory [4]. Interspecific competition [5,6] is pervasive among coral communities, and is important in maintaining their viability [7,8]. Heterospecific competition of corals with algae reduces coral growth and survivorship [9,10]. In corals, spatial arrangement, orientation and aggregation may be a key mechanism contributing to species coexis- tence on coral reefs [11,12]. Maintaining coral reef popu- lations in the face of large scale degradation and phase- shifts on reefs depends critically on recruitment [13,14], maintenance of grazing fish and urchin populations [15], clade of symbiotic zooxanthellae [16] and management of human activities related to agricultural land use and coastal development [17]. It is the generation of scientific information and capacity-building with the help of eco- and research-tourism that we wish to address here, par- ticularly as such non-governmental oganisations come un- der threat in a period of climate change. 1.2 Climate Change and the End of Tourism? Tourism is a vital economic driver for many countries; not least some of the poorest countries in the world. The literature on climate change and sustainable tourism is somewhat fragmented, largely consisting of individual case-studies [18-20], although all agree on the cross- border nature of tourism. Burns and Bibbings [21] in their paper on socio-cultural aspects of tourism, discuss the changes in demand that climate change brings to the tourism agenda. They take a series of research questions based around ethical consumption, sustainability, policies, actions and communication, and indicate that social ben- eficial behaviour for all concerned is the way forward; simply sticking to adaptation as the default response to climate change will hasten the ‘end of tourism’.  Sustainable Tourism and Management for Coral Reefs: Preserving Diversity and Plurality in a Time of Climate Change251 1.3 Ecotourism and Research Tourism The ‘compulsive’ appetite for increasing mobility [22,23] allied to a social desire for extraordinary ‘peak experie- nces’ [24] has led to the modern ‘ethical consumer’ for tourism services [22,25] derived from the ‘experiential’ and ‘existential’ tourist of the 1970s [26]. The model un- derlying sustainability tourism is complex with contra- dictory elements [27]―for example irrefutable evidence about the consequences of climate change yet a lack of information on how to respond at a community level. Se- veral organisations have taken the concept of ecotourism further to research tourism, whereby the tourist gets to work on research projects under the supervision of rec- ognised researchers. Two organisations that have devel- oped research tourism are Operation Wallacea, based in the UK, and the Earthwatch Institute, based in the USA but with global coverage and offices in several countries. Here we identify the ways in which both organisations use research tourism to benefit ecosystem diversity and conservation. We then show how an Earthwatch progr- amme on coral reefs generated scientific information to inform management strategies in Jamica. This is followed by a description of a capacity-building programme in Belize, which developed specific action plans for tourism. We discuss how implementation of those plans can help preserve coral reef ecosystems in times of climate change. 1.4 Operation Wallacea Operation Wallacea (OpWall; http://www.opwall.com) is a series of biological and conservation management re- search programmes that operate in remote locations across the world. These expeditions are designed with specific sustainable conservation aims in mind―from identifying areas needing protection, through to implementing and assessing conservation management programmes. Uni- versity academics, who are specialists in various aspects of biodiversity or social and economic studies are con- centrated at the target study sites giving volunteers the opportunity of working on a range of research projects. The research has resulted in several publications in peer- reviewed journals (e.g., 14 papers published on coral reefs in the Wakatobi Marine National Park, Indonesia, from 2003-2009―details at: http://www.opwall.com/Library/ Indonesia/coral%20reefs.shtml), the discovery of 30 ver- tebrate species new to science, 4 ‘extinct’ species being re-discovered and $ 2 million levered from funding agen- cies to set up best practice management examples at the study sites. A research and conservation strategy has been devel- oped and is applied in 4 stages at each of the sites. This includes an initial assessment of the biological value of the site (stage 1). If the site is accepted into the OpWall programme then an ecosystem monitoring programme is established to determine the direction of change (stage 2). If this reveals a continuing decline then a programme for monitoring socio-economic change in adjacent communi- ties is established to determine how these communities interact with the study site (stage 3). Once these stage 2 and stage 3 data are obtained funding applications are submitted to establish a best practice example of conser- vation management and the success of these programmes are then monitored (stage 4). There is obviously some considerable overlap between these stages and stage 1 projects can still be running in addition to a stage 4 pro- gramme in order to add data to understanding the eco- system requirements of target species or adding to the overall species lists for previously un-worked taxa. Throughout these 4 stages of development, an addi- tional objective of the programmes is to develop financial benefits to local communities from protecting the studied areas. Wherever possible the expeditions are organised in close co-operation with the local communities and sub- stantial benefits accrue to those communities through providing accommodation, food, transport, manpower etc. In addition to the direct economic input from the expedi- tions though, emphasis is placed on the development of businesses that can provide alternative incomes to local communities (e.g., coral growing for the aquarists market in Kaledupa, Wildlife Conservation Product prices for cashews, chocolate and coffee in Indonesia and Honduras etc.) in the additional funding applications made. 1.5 Earthwatch Institute Earthwatch (http://www.earthwatch.org/) is an interna- tional environmental charity which is committed to con- serving the diversity and integrity of life on earth to meet the needs of current and future generations. They work with a wide range of partners, from individuals who work as conservation volunteers on research teams through to corporate partners (such as HSBC), governments and institutions. Earthwatch has a global reach, with offices in Oxford (UK), Boston (USA), Melbourne (Australia) and Tokyo (Japan). Earthwatch engages people world- wide in scientific field research and education to promote the understanding and action necessary for a sustainable environment. Research volunteers work with scientists and social scientists around the world to help gather data needed to address environmental and social issues. By directly supporting field research and educating and en- gaging thousands of people, Earthwatch has made a sig- nificant contribution to achieving a sustainable environ- ment over the past 35 years. Apart from many papers in peer-reviewed journals, Earthwatch has had other suc- cesses in sustainable ecosystems. These include securing Ramsar status (see: http://www.ramsar.org/index_about_ ramsar.htm) for Lake Elmenteita in Kenya and diverting shipping lanes to help dolphin conservation in the waters around Spain. In 2008, Earthwatch Australia won an En- vironment Award for supporting a research project on Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSSM  Sustainable Tourism and Management for Coral Reefs: Preserving Diversity and Plurality in a Time of Climate Change Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSSM 252 Forest Marsupials (see: http://www.earthwatch.org/about- us/results/) These individuals were chosen because they had direct contact with both NGOs (Non-governmental organisa- tions) and CBOs (Community-based organisations), and the government Fisheries Department, thus maximising exposure of capacity-building while keeping the numbers of participants within workable limits [29]. Discussions, led by the Facilitator employed a modified nominal group technique [30] to identify priorities related to personal action plans. Four rounds were employed; round one was based on the Delphi technique and further rounds on the nominal group technique approach [31]. Those rounds resulted in a number of management proposals [32], and an action plan for ecotourism. Both these organisations have well evidenced strateg- ies and outputs regarding community and ecosystem sus- tainability. It is the long-term strategies of both organisa- tions that underpin their successes in this area; they are in for the long haul, and can effect conservation in a differ- ent way to a standard 3 year research grant. 2. Methods 2.1 Jamaican Coral Reef Sites and Sampling Studies were conducted using SCUBA at five sites [Rio Bueno (18° 28.805' N; 77° 27.625' W), Dancing Ladies (18° 28.369' N; 77° 24.802' W), M1 (18° 28.337' N; 77° 24.525' W), Dairy Bull (18° 28.083' N; 77° 23.302' W), and Pear Tree Bottom (18° 27.829' N; 77° 21.403' W)] over a seven year period (2002-2009) along the fringing reefs surrounding Discovery Bay, Jamaica. GPS coordinates were determined using a hand-held GPS receiver (Garmin Ltd.). For all sites, four haphazardly located transects, each 15 m long and separated by at least 5 m, were laid at be- tween 5-8.5 m depth, to minimise variation in growth rates due to depth. Corals 2 m either side of the transect lines were photographed and surface areas measured with flexible tape as described previously using SCUBA [see 28]. To increase accuracy, surface areas rather than di- ameters of live non-branching corals were measured. 3. Results 3.1 Corals on the Fringing Reefs of Jamaica As the viability of small coral colonies over time can indicate reef resilience [see 28], as part of an Earthwatch project on coral reefs of Jamaica, Figure 1 shows the annual changes in the colony numbers of the smallest size class (0-250 mm2 surface area) each year from 2002-2008 for one massive species of coral, Diploria strigosa. There was a reduction in the smallest size class at all the sites in 2006, with subsequent increases at all sites in 2007 and 2008. This behaviour was similar to that observed with other coral species [28]. The only bleaching event that significantly impacted the reef sites during the study period was the mass Car- ibbean bleaching event of 2005. Analysis of satellite data showed that there were 6 degree heating weeks (dhw) for sea surface temperatures in September and October 2005 near Discovery Bay, data which was mirrored by data loggers on the reefs [see 28]. Six dhw are equivalent to six weeks of sea surface temperatures (SSTs) one degree Celsius greater than the expected summer maximum. This work was conducted at Discovery Bay during March 26-April 19 in 2002, March 18-April 10 in 2003, July 23-August 21 in 2004, July 18-August 13 in 2005, April 11-18 in 2006, December 30 in 2006-January 6 in 2007, and July 30-August 16 in 2008. 2.2 Capacity Building Exercise in Belize for Coral Reefs Interestingly, in 2005, the year after hurricane Ivan, the most severe storm to impact the reef sites over the study period, there was a slight reduction in the numbers of the smallest size classes, particularly notable at Dairy Bull. The capacity building team consisted of one officer from the Belize Fisheries Department, three senior officers from NGOs involved in managing Belize MPAs (TIDE, TASTE and Friends of Nature), and myself from the UK. Figure 1. Graphs of annual changes in the colony numbers of the smallest size class (0-250 mm2 surface area) from 2002-2008 for Diploria strigosa at Rio Bueno (RB), M1 (M1), Dancing Ladies (DL), Dairy Bull (DB), and Pear Tree Bottom (PTB)  Sustainable Tourism and Management for Coral Reefs: Preserving Diversity and Plurality in a Time of Climate Change253 Figures 2(a)-2(b) show total colony numbers of me- dium-large surface area corals (i.e., > 250 mm2 surface area) during the same period, for the massive corals Dip- loria strigosa and Colpophyllia natans. These data show that while recruitment of small corals is returning after the major bleaching event of 2005, lar- ger corals are not necessarily so resilient, and so need careful management if the reefs are to survive such major extreme events. 3.2 Action Plan to Foster Ecotourism for Coastal Zone Management of Coral Reefs Table 1 illustrates a summary action plan developed for ecotourism and coastal zone management. Implementa- tion of that plan requires a series of tactics revolving around a number of themes: organisation and managem- ent, education, resources, and policy development. It is important to have clear and disinterested leadership and a decision-making process that links local stakeholders with ecotourism organisations, and is widely respected to reduce the possibility that differences do not deteriorate into conflict. Surveys need to be conducted to evaluate level of success and failure. Too often, programmes have been formed and implemented but end results have not been evaluated. Surveys should be carried back to stake- holders for a presentation to establish further steps, and communication is an essential feature of maintenance of ecotourism and conservation. The capacity-building ex- ercise helped in continuing the link between the Earth- watch Institute and the Fisheries Department in the Be- lize Government [29,32]. Year Colony numbers (a) Year Colony numbers (b) Figure 2. Graphs of annual changes in the total colony numbers of medium-large size corals (> 250 mm2 surface area) from 2002-2008 for: Diploria strigosa (a) and Colpophyllia natans (b) at Rio Bueno (RB), M1 (M1), Dancing Ladies (DL), Dairy Bull (DB), and Pear Tree Bottom (PTB) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSSM  Sustainable Tourism and Management for Coral Reefs: Preserving Diversity and Plurality in a Time of Climate Change 254 Table 1. Action plan for ecotourism and management of coral reefs from the capacity building exercise conducted in Belize Objective Activity Output Outcome Impact To improve networking between local stakeholders and ecotourism partners. To improve awareness of climate change issues for local stakeholders Organise meetings with partners and share infor- mation. Hold meetings between ecotourism partners and distribute climate change information among part- ners and stakeholders Distributing research papers and informa- tion among other researchers and part- ners and local stake- holders. Development of projects linking ecotourism part- ners with NGOs, CBOs and local stakeholders Improved conservation of coastal zone species Will create better awareness and will assist in deci- sion-making at local and national levels. 4. Plurality and Communication Research ecotourisism organisations such as those men- tioned above are important in that they provide first hand experience of living and working in pluralistic cultures, and are a complement to the information available via broadcasting and over the internet. In a digital age, where anyone can gain access to opinions through the internet, there is a worry that loss of plurality might be a problem [15]. In order to foster the virtues of plurality and differ- ence inherent in civil societies our cultures need at the same time points of connection and mutual recognition, where differences can be asserted, acknowledged and accommodated. Can that public space for the common recognition of difference be created in the internet age? Must plurality be remodelled anew? Debate on these questions is important, if we are to preserve diversity in all its aspects. Diversity and pluralism―a problem or an answer for policy development? Isaiah Berlin defined negative liberty as the absence of constraints on, or interference with, agents’ possible ac- tion [33]. Greater “negative freedom” meant fewer re- strictions on possible action. Berlin associated positive liberty with the idea of self-mastery, or the capacity to determine oneself, to be in control of one’s destiny. While Berlin granted that both concepts of liberty represent valid human ideals, as a matter of history the positive concept of liberty has proved particularly susceptible to political abuse [34]. Intimately connected with this pluralist thesis is a be- lief in freedom from interference, especially by those who think they know better, that they can choose for us in a more enlightened way than we can choose for our- selves. This is relevant to sustainability and tourism, as under neoliberalism, everything can become commodi- fied, from products and services to the environment. De- velopment of policy by ‘participation’ is often far from participatory and representative [35-36]. Instead of a spl- endid synthesis there must be a permanent, at times painful, piecemeal process of untidy trade-offs and care- ful balancing of contradictory claims [e.g., 32,37]. New global rights discourses and international law poi- nt towards sustainable relationships between different cultural groups and the environment. The results from research tourism can help to transform the development of resources, for example in Jamaica and elsewhere in the Caribbean [28,38-39] to the preservation of resources [40]. Research being conducted by the Opwall and Ear- thwatch research tourists can not only help immeasurably in obtaining important scientific information, such as that described in this paper for the coral reefs of Jamaica, but also build bridges between stakeholder communities and organisations. Examples of where this has been success- ful, using protocols similar to those mentioned in Table 1, are in Belize [32] and in Cayos Cochinos in Honduras [41]. Ecotourism can help conserve both biological and social diversity. As the political reality of climate change becomes more evident, the valuable tools from research tourism need to be preserved in the face of increasing pressures. As Lois MacNiece wrote [42]: World is suddener than we fancy it. World is crazier and more of it than we think. Incorrigibly plural. 5. Acknowledgements I thank the Earthwatch Institute and the Oak Foundation (USA) for funding, Mr. Anthony Downes, Mr. Peter Gayle, and the staff of the Discovery Bay Marine Labo- ratory, Jamaica, for their invaluable help and assistance, and to volunteers for their help underwater measuring corals. REFERENCES [1] T. A. Gardner, I. M. Côté, J. A. Gill, A. Grant and A. R. Watkinson, “Long-Term Region-Wide Declines in Car- ibbean Corals,” Science, Vol. 301, No. 5635, 2003, pp. 958-960. [2] D. R. Bellwood, T. P. Hughes, C. Folke and M. Nyström, “Confronting the Coral Reef Crisis,” Nature, Vol. 429, No. 6994, 2004, pp. 827-833. [3] J. H. Connell, “Diversity in Tropical Rain Forests and Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSSM  Sustainable Tourism and Management for Coral Reefs: Preserving Diversity and Plurality in a Time of Climate Change255 Coral Reefs,” Science, Vol. 199, No. 4335, 1978, pp. 1302-1310. [4] C. S. Rogers, “Hurricanes and Coral Reefs: The In- ter-mediate Disturbance Hypothesis Revisited,” Coral Reefs, Vol. 12, No. 3-4, 1993, pp. 127-137. [5] P. Stoll and D. Prati, “Intraspecific Aggregation Alters Competitive Interactions in Experimental Plant Commu- nities,” Ecology, Vol. 82, No. 2, 2001, pp. 319-327. [6] S. Hartley and B. Shorrocks, “A General Framework for the Aggregation Model of Coexistence,” Journal of Ani- mal Ecology, Vol. 71, No. 4, 2002, pp. 651-662. [7] R. H. Karlson, “Dynamics of Coral Communities,” Klu- wer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1999. [8] R. H. Karlson, H. V. Cornell and T. P. Hughes, “Aggre- gation Influences Coral Species Richness at Multiple Spa- tial Scales,” Ecology, Vol. 88, No. 1, 2007, pp. 170-177. [9] D. Lirman, “Competition between Macroalgae and Corals: Effects of Herbivore Exclusion and Increased Algal Bio- mass on Coral Survivorship and Growth,” Coral Reefs, Vol. 19, No. 4, 2001, pp. 392-399. [10] S. J. Box and P. J. Mumby, “Effect of Macroalgal Com- petition on Growth and Survival of Juvenile Caribbean Corals,” Marine Ecology Progress Series, Vol. 342, 2007, pp. 139-149. [11] J. A. Idjadi and R. H. Karlson, “Spatial Arrangement of Competitors Influences Coexistence of Reef-Building Corals,” Ecology, Vol. 88, No. 10, 2007, pp. 2449-2454. [12] M. J. C. Crabbe, “Topography and Spatial Arrangement of Reef-Building Corals on the Fringing Reefs of North Jamaica May Influence their Response to Disturbance from Bleaching,” Marine Environmental Research, Vol. 69, No. 3, 2010, pp. 158-162. [13] T. P. Hughes and J. E. Tanner, “Recruitment Failure, Life Histories and Long-Term Decline of Caribbean Corals,” Ecology, Vol. 81, No. 8, 2000, pp. 2250-2263. [14] S. L. Coles and E. K. Brown, “Twenty-Five Years of Change in Coral Coverage on a Hurricane Impacted Reef in Hawai’i: The Importance of Recruitment,” Coral Reefs, Vol. 26, No. 3, 2007, pp. 705-717. [15] P. J. Mumby, A. Hastings and H. J. Edwards, “Th- resholds and the Resilience of Caribbean Coral Reefs,” Nature, Vol. 450, No. 7166, 2007, pp. 98-101. [16] M. Stat, E. Morris and R. D. Gates, “Functional Diversity in Coral-Dinoflagellate Symbiosis,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, Vol. 105, No. 27, 2008, pp. 9256-9261. [17] C. Mora, “A Clear Human Footprint in the Coral Reefs of the Caribbean,” Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Bio- logical Sciences, Vol. 275, No. 1636, 2008, pp. 767-773. [18] E. Tompkins, S. Nicholson-Cole, L. Hurlston, E. Emily Boyd, G. Brooks Hodge, J. Clarke, G. Gray, N. Trotz and L. Varlack, “Surviving Climate Change in Small Is- lands―a Guidebook,” Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, Norwich, 2005. [19] A. Perry, “The Mediterranean: How Can the World’s Most Popular and Successful Tourist Destination Adapt to a Changing Climate?” In: Hall, C. M. and Higham, J. Eds., Tourism, Recreation and Climate Change, Channel View, Clevedon, 2005, pp. 86-96. [20] J. Higham and M. Hall, “Making Tourism Sustainable: The Real Challenge of Climate Change?” In: Hall, C. M. and Higham, J. Eds., Tourism, recreation and climate change, Channel View, Clevedon, 2005, pp. 301-307. [21] P. Burns and L. Bibbings, “The End of Tourism? Climate Change and Societal Challenges,” 21st Century Society, Vol. 4, No. 1, 2009, pp. 31-51. [22] P. Burns, “Tribal Tourism-Cannibal Tours: Tribal Tour- ism to Hidden Places,” In: Novelli and Marina, Eds., Niche Tourism: Contemporary Issues, Trends, Cases, El- sevier, Oxford, 2005, pp. 101-110. [23] J. Urrey, “Cars, Climates and Complex Futures,” Depart- ment of Sociology, Lancaster, 2006. [24] A. Holden, “Environment and Tourism,” 2nd Edition, Routledge, London, 2008. [25] D. Fennell, “Ethical Tourism,” Routledge, London, 2006. [26] E. Cohen, “A Phenomenology of Tourist Experiences,” Sociology, Vol. 13, No. 2, 1979, pp. 179-201. [27] T. Patterson, S. Bastianoni and M. Simpson, “Tourism and Climate Change: Two Way Street, or Vicious/Virtuous Circle?” Journal of Sustainable Tourism, Vol. 14, No. 4, 2006, pp. 339-348. [28] M. J. C. Crabbe, “Scleractinian Coral Population Size Structures and Growth Rates Indicate Coral Resilience on the Fringing Reefs of North Jamaica,” Marine Environ- mental Research, Vol. 67, No. 4-5, 2009, pp. 189-198. [29] M. J. C. Crabbe, E. Martinez, C. Garcia, J. Chub, L. Cas- tro and J. Guy, “Is Capacity Building Important in Policy Development for Sustainability? A Case Study Using Ac- tion Plans for Sustainable Marine Protected Areas in Be- lize,” Society and Natural Resources, Vol. 23, No. 2, 2010, pp. 181-190. [30] J. A. Sample, “Nominal Group Technique: An Alterna- tive to Brainstorming,” The Journal of Extension, Vol. 22, No. 2, 1984. http://joe.org /joe/1984march/iw2.html [31] T. V. McCance, D. Fitzsimons, S. Keeney, F. Hasson and H. P. McKenna, “Capacity Building in Nursing and Mid- wifery Research and Development: An Old Priority with a New Perspective,” Journal of Advanced Nursing, Vol. 59, No. 1, 2007, pp. 57-67. [32] M. J. C. Crabbe, E. Martinez, C. Garcia, J. Chub, L. Cas- tro and J. Guy, “Identifying Management Needs for Sus- tainable Coral-Reef Ecosystems,” Sustainability: Science, Practice & Policy, Vol. 5, No.1, 2009, pp. 42-47. [33] T. Gardam, “The Purpose of Plurality,” In: Gardam, T. and Levy, D. A. Eds., The Price of Plurality, The Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, Oxford, 2008, pp. 11-21. [34] I. Berlin, “Liberty,” Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2002. [35] G. Crowder, “Isaiah Berlin: Liberty and Pluralism,” Polity, Key Contemporary Thinkers Series, Cambridge, 2004. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSSM  Sustainable Tourism and Management for Coral Reefs: Preserving Diversity and Plurality in a Time of Climate Change Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JSSM 256 [36] R. Chambers, “Paradigm Shifts and the Practice of Par- ticipatory Research and Development,” In: Nelson, N. and Wright, S. Eds., Power and Participatory Development: Theory and Practice, Intermediate Technology Publica- tions, London, UK, 2000, pp. 30-42. [37] B. Cooke and U. Kothari, “Participation: The New Tyr- anny?” Zed Books, New York, 2001. [38] M. J. C. Crabbe, “Challenges for Sustainability in Cul- tures Where Regard for the Future May not be Present,” Sustainability: Science, Practice & Policy, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2006, pp. 57-61. [39] L. M. Carr and W. D. Heyman, “Jamaica Bound? Marine Resources and Management at a Crossroads in Antigua and Barbuda,” Geographical Journal, Vol. 175, No. 1, 2009, pp. 17-38. [40] P. West, “Conservation Is our Government now: The Politics of Ecology in Papua New Guinea,” Duke Univer- sity Press, Durham and London, 2006. [41] K. V. Brondo and L. Woods, “Garifuna Land Rights and Ecotourism as Economic Development in Honduras’ Cayos Cochinos Marine Protected Area,” Ecological and Environmental Anthropology, Vol. 3, No. 1, 2007, pp. 2-18. [42] L. MacNiece, “Collected Poems,” Faber & Faber, London, 1966. |