Beijing Law Review, 2012, 3, 15-23 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/blr.2012.32003 Published Online June 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/blr) 15 The Legitimacy of Using Excessive Force during Civil Policing among Israel’s Border Guard Police Officers Efrat Shoham, Shirley Yehosha Stern Criminology Department, Ashkelon Academic College, Ashkelon, Israel. Email: shoham@netzer.org.il, Shirley_r@bezeqint.net Received April 7th, 2012; revised May 6th, 2012; accepted May 18th, 2012 ABSTRACT This research aims to examine two main issues: What is the level of legitimacy attributed to the use of excessive force during civil policing among Border Guard Police officers, compared to ordinary police officers and civilians, and how legitimate is it to involve external supervisory bodies when there is a suspicion of unreasonable or unjusti- fied use of force? Every democratic state faces the need to find a balance between two theoretical and normative models: on the one hand the “Due Process Model” which aims to protect the rights of suspected, accused or con- victed individuals and, on the other, the “Crime Control Model”, mainly based on an efficient and economical judi- cial system, and the need to provide society with a sense of security on a daily basis. The research assumption is that police officers as a whole, and specifically members of the Border Police who handle disturbances of peace as well as legal violations, alongside the necessity to combat security threats, tend to hold closer to the “Crime Control Model” and less to the “Due Process Model”, which the police officers find hinders their ability to effectively man- age crime. In order to examine this assumption, an attitude questionnaire was constructed, examining the degree of legitimacy for the use of excessive force on the one hand, and supervision of the use of excessive force in police work on the other. The questionnaire was distributed to 140 Border Guard officers and ordinary police officers serv- ing in the Southern Command of the Israeli Police. In addition, 60 questionnaires were distributed to ordinary ci- vilians. Our findings show a high level of support among police officers and civilians alike for the use of excessive force in civil policing operations. The highest level of legitimacy towards the use of excessive force was found, as expected, among the Border Guard officers. The research concludes that the attitudes of the police officers, espe- cially those of the Border Guard who are fighting a constant battle against security threats alongside the war against crime, greatly restrict the power of external and internal supervision mechanisms to effectively supervise the use of unreasonable force during civilian policing. Keywords: Excessive Force; Police; Legitimization; Israel 1. Introduction The concept of policing refers to the formal and informal processes and operations whose purpose is the preserva- tion of order and security in any given society (Reiner [1]). In his book on the functions of policing in modern society, Bittner [2] states that the essence of a police or- ganization is its authority and ability to enforce. The ex- tensive use of the power of enforcement (including physical force, deprivation of freedom, and infringement of civil rights) to attain a broad range of objectives seems to be the exclusive characteristic of the work of the po- lice (Gimshi [3]; Skolnick & Fayfe, [4]). Rather than being merely one of an array of means at the disposal of the police, the use of the powers of enforcement is the cen- tral component of their work, distinguishing it from other institutions in both the public and private sectors. The granting of the authority to use force is based, in the opinion of Gimshi [3], on a fundamental faith that the use of force will be reasonable and will be exercised in in- stances where it is lawful and justified. Over the past three decades, various public commis- sions have explored the issue of use of force by police. Their findings indicate, among other things, that police activity is dualistic, based on discrepancies between em- phasizing the limits of use of force and turning a blind eye and allowing it (The State Comptroller [5]). At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the office of the State Comptroller published the results of the official inquiry of complaints about police violence and improper behavior by police officers or the faulty performance of their duties. The report revealed that out of 6702 com- plaints, 3916 concerned unlawful use of force. The report states that most of the cases were closed due to a lack of Copyright © 2012 SciRes. BLR  The Legitimacy of Using Excessive Force during Civil Policing among Israel’s Border Guard Police Officers 16 sufficient evidence as a result of conflicting accounts of the incident by the complainant and the suspect and a lack of objective evidence to support either one of them. The new version of the Police Ordinance (1971) states that: “The use of force will not be permitted unless the law empowers such use, when the job of the police offi- cer requires this, and it is necessary and justified under the circumstances”; In addition it states that: “Police of- ficers are authorized to use force only in such instances as are detailed in the orders of National Headquarters, and only the degree of force essential to attain the object- ive for which the use of force is necessary. In the polic- ing reality in Israel, issues of crime-fighting and of in- ternal security coexist. As a result, the work of the Israel Police must reconcile the centralist military ethos with the collective community one. This imperative is espe- cially conspicuous in prominent units like the Border Guard. The organizational structure of the Border Guard is that of a “military force,” dealing primarily with mat- ters of internal security and public order, although they also handle law enforcement and crime-fighting. The Border Guard does not ordinarily have territorial respon- sibility; its responsibility is more functional or mission- specific as in matters dealing with terror, security, dis- ruptions of order, crime, and illegal residents, especially from the area under the control of the Palestinian Gov- ernment. The unit and its personnel are subordinate to the Israel Police and are considered to be police. The unit serves as a mobile reserve force to handle disturbances or complex security events. Border Guard units are equipped with weapons similar to those of soldiers in field units and part of their training is within the military framework (Gimshi, [3]). An Israel Police Code of Ethics was for- mulated in 1998 and expanded during 2004 (Werner & Tsemach, [6]). The purpose of the expansion was, to a great extent, to reconcile the centralist military ethos of the war on terror with the collective community ethos, which, as we have said, coexist in policing activities in Israel (on the possible influences of the militarization of policing functions and the war on terror, see: Bayley & Weisburd, [7]; Weisburd & Braga, [8]; Herzog, [9]; Weisburd, Jonathan & Perry, [10]). The present study aims to examine the level of legiti- macy attributed to the use of excessive force during civil policing among Border Guard officers. 1.1. Legitimacy of the Use of Force in Policing Functions The use of excessive force by police is an extremely complex phenomenon and as a result the decision to re- sort to violence is fraught with many different factors influencing the confrontation and the reciprocal relation- ship between police officer and citizen. It is therefore difficult to conceptualize and define police excessive force as can be seen by the abundance of definitions of force that is necessary, permissible, excessive, or rea- sonable in police activity (Werner & Tsemach [6]). Ac- cording to Skolnick and Fayfe [4], an examination of the degree of legitimacy accorded to the use of physical force in policing activity should address three principal situations: 1) By virtue of the legal authority vested in the police officer on duty, to use force in situations specified by the law or police regulations; 2) The use of physical force to prevent harm to the po- lice officer himself or to execute a judicial decree for the arrest of an individual for purposes of interrogation, tes- tifying, or other obligations; 3) The degree of legitimacy with which police per- sonnel attribute to the use of excessive force in the line of duty is associated, among other things, with the issue of their professional identity (Reiner, [1]). The professional literature distinguishes between two main perceptions of the function of policing: the traditional narrow perception of crime-fighting, and the broader alternative view of community policing or community-focused policing. At the same time, it is noteworthy that these differing per- ceptions of the job operate in the context of the structure and policy of the police. The police officers’ perception of their function and the circumstances of their response also depend on the structure of the population, on the level and types of crime, on the inter group tensions in society, on changes in the law and adjudication, and on the legitimacy of the police in society and society’s atti- tudes toward its police (Bayley & Weisburd [7]; Jona- than, [11]; Braga & Weisburd, [12]; Weisburd, Jonathan & Perry [10]). The crime-centered perception of the job focuses on preventing potentially dangerous events by mounting operations targeting criminals and prioritizing this activ- ity over other police work that is considered less prestig- ious, such as settling disputes between neighbors, qual- ity-of-life crimes, and others. This preference results from the fact that the police officer does not consider it his job to resolve problems that disturb the community, but rather only to fight crime (Langworthy & Travis [13]). The officer that sees himself as a protector of soci- ety and as an individual who risks his life every day for others in society experiences a daily lack of co-coopera- tion, alienation, and various manifestations of antago- nism (Amir, [14]). Interviews of Border Guard police officers conducted by Carmeli and Shamir [15], for ex- ample, reveal that they see themselves as subjected to great risk, ascribed to a high level of friction with a hos- tile population. These Border Guard police also thought that the law in Israel is “weak” and does not provide so- lutions for police officers in the field. According to them, Copyright © 2012 SciRes. BLR  The Legitimacy of Using Excessive Force during Civil Policing among Israel’s Border Guard Police Officers 17 the law’s weakness is one of the things that drives some of them to resort to use of force. In the interviews con- ducted with “men in blue”, i.e., the regular, civilian po- lice, in the same study (Carmeli & Shamir, [15]), these subjects claimed that the law is very vague about the use of force, riddled with lacunae and sidestepping many situations in which the police find themselves. The offi- cers described their feelings of being left alone in the field, without sufficient guidelines or backup. In such a situation, the police officer is likely to consider the laws and administrative regulations an unwelcome burden, which interferes with the efficiency of the war on crime, considered by these police officers as being of supreme importance (Sheptycki [16]). 1.2. The Ethos of Policing and the Use of Excessive Force A professional identity based on crime fighting contrib- utes new ways and means, some of which are violent, to achieve the organization’s legal objectives and missions. Consequently, toughness and manifestations of violence are accepted as important operating principles (Amir, [14]; Goldsmith, [17]). In the late 1970, a new ethos of a police force that focuses its work on the community gradually appeared. Community policing, as opposed to the traditional enforcement policing, extends the role of the police to embrace additional matters, such as reduc- ing the fear of crime, preserving the public order, resolv- ing conflicts, improving quality of life in the community, etc. (Walker & Katz [18]). The community policing, which places the individual and his rights at the center of police endeavor, (Fuller, [19]) represents an organiza- tional philosophy that demands ways of thinking that are different from those of traditional policing (Dempsey & Forst [20]; Skolnick, [21]). With this organizational per- ception, the citizen is transformed from potential suspect to partner in defining the problems and finding ways to solve them (Skogan, [22]). This broad, associative per- ception is expected to introduce a search for different and additional modi operandi that will render the use of ex- cessive force in police work far less prevalent. Although in the early 1990s the Israel Police decided to implement the community policing strategy in Israel, community policing as an inclusive program does not seem to have actually been put into practice, nor has it brought about any fundamental change in the perceptions and behaviors of police in the field (Weisburd, Shalev, & Amir, [23]). These scholars argue (ibid.) that the failure to implement community policing in Israel stems from a number of factors related to Israeli society in general and the police in particular. Among these factors the re- searchers cite the security orientation of the police and the militarization of police work in Israel, primarily due to having to deal so often with Palestinian terror. Jonathan [11] asserts that the degree of legitimacy granted by the Jewish public in Israel to the various ac- tivities of the police is closely related to the level of the terror threats during any given period. According to her, at times when acts of terror endanger security, the Jewish public in Israel gives increased legitimacy to intensive policing activities that favor surveillance, distrust, and the speedy exertion of force over a service approach and assistance to citizens. Gimshi [3] claims that the bellig- erent ethos that typifies the organizational culture in- creases the inclination to use excessive force during po- lice activities. The police officer receives a mixed mes- sage regarding the law: on the one hand the law is the foundation of the structure of society and he must there- fore respect it, yet at the same time it can be an obstacle to the successful performance of his duty. The State Comptroller [5] expressed this as follows: There is a mixed message in the police in all matters concerning police violence, manifest in the discrepancy between the attitude presented in their training, empha- sizing the boundaries of the use of force, and the attitudes of the field commanders, who adopt a policy of “turning a blind eye” and “a conspiracy of silence”. 1.3. How Can You Supervise the Supervisors? There is broad consensus among police studies research- ers that police organizational culture does a great deal to mold the work of policing, especially in field policing operations (Crank, [24]; Skolnick, [21]). The police or- ganizational structure is an amalgam of norms, values, and patterns of career goals and lifestyles shared by po- lice in the field that are unlike those of the general popu- lation (Dempsey & Forst [20]). Skolnick [21] claims that the characteristics of police work create certain propensi- ties in the character of police officers, such as authori- tarianism, suspicion, conservatism, hostility, withdrawn- ness, and cynicism. He adds that field police function with the sense of danger and risk of physical injury. The authority vested in them makes them feel powerful and conscious of the impact they have on those with whom they come in contact. He also claims that they feel that they can rely on no one but fellow police officer who experience the same events and risks that they do. Goldsmith [17] claims that direct friction with human wickedness makes police in the field suspicious and dis- trustful. This friction produces a supportive organiza- tional solidarity in the face of a threatening external world. Alongside the intense social solidarity, the evolve- ing organizational culture results in suspicion, cynicism and a lack of trust in the outside world, together with the “blue code of silence” phenomenon that constitutes a protective barrier against anyone who is not a police of- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. BLR  The Legitimacy of Using Excessive Force during Civil Policing among Israel’s Border Guard Police Officers 18 ficer (Forst, [25]). Differing from the flank of researchers who claim that it is the sense of mission, propensity for action, pessimistic and suspicious attitude to their sur- roundings, social isolation, code of loyalty to fellow of- ficers and adherence to the silence of police work (Reiner, [1]) that mold the “working personality” of the police officer, there are other researchers (see for example Ek- envall, [26]) who argue that internalization of the code of silence and refusal to inform on a fellow officer are built into the socialization process even before the individual enlists in the police force. Every democratic state faces the need to find a balance between two basic forms of protection: on the one hand protecting the rights of suspected, accused or convicted individuals and, on the other, the need to provide society with a sense of security on a daily basis. The need to reach a balance between these two forms of protection very much reinforces the existing, built-in tension be- tween two theoretical and normative models, which mold the criminal process in democratic states (Packer, [27]). “The Crime Control Model”, based on the public in- terest to uphold the law, is mainly an efficient and eco- nomical judicial system and “The Due Process Model”, based on the will to protect citizens from the govern- ment’s extensive use of force, is more of a cautious judi- cial system, which establishes for itself a set of checks and balances in order to maintain the credibility of its decisions. The Crime Control Model sets the need to protect the general public and the social order as a prin- ciple value, including the inspiration to shift the weight of criminal procedures to the preliminary stages of arrest and investigation in order to prevent long and costly legal proceedings (Larnau, [28]). Making the fight against crime a central value may result in strengthening the legitimization for the use of various means of force, including those which do not fully or partially fit the order which regulates the use of force in policing activities. The “Due Process” model, which views with great cre- dibility the value behind law enforcement, looks to bal- ance between the innate weakness of the civilian against the vast power of law enforcement bodies. The purpose of this approach is to protect the civilians and their rights from the arbitrary use of force by representatives of law enforcement systems. By this model, the center of grav- ity is placed on decisions made throughout the criminal process in court, which is perceived as a neutral and un- biased factor. This model, which places in the center civil liberties and the right to freedom and dignity, requires the existence of stringent controls and regulations over the various means which the police employ in the fight against crime. The research hypothesis is that police officers as a whole, and specifically members of the Border Police, who handle throughout their work disturbances of peace, and violations of law, alongside the necessity to combat security threats, tend to hold closer to the Crime Control Model and less to the Due Process Model, which is grasped by the officers as hindering the police in its ef- fective management of crime. Against the backdrop of the expansion of the ethical code of the Israel Police in the early twenty-first century on the one hand, and the deepening of the policing roles assigned to special units like the Border Guard on the other, we aim to examine two principal questions: 1) How legitimate is the use of excessive force in the framework of civil policing? 2) How legitimate is it to involve external supervisory bodies when there is a sus- picion of unreasonable or unjustified use of force? To deal with these questions, this study is designed to compare the degree of legitimacy attributed to excessive force throughout police work by Border Guard officers and regular field police officers. The research also com- pares the level of legitimacy attributed to excessive force between police officers and ordinary civilians in order to identify the characteristics of the police organizational sub-culture. The assumption of the study is that Border Guard officers attribute the highest level of legitimacy to the use of excessive force and adherence to the culture of keeping silent, and ordinary civilians give it the least. 2. Method In order to examine this assumption, an attitude ques- tionnaire was constructed, examining the degree of le- gitimacy for the use of excessive force on the one hand, and supervision of the use of excessive force in police work on the other. This questionnaire was modeled after the role perception questionnaire developed by Worden [29] and adapted to the legal reality in which the police operate in Israel. The questionnaire includes 20 utter- ances to which the respondent was asked to indicate the degree of his agreement on a scale from 1 to 5. Some of the utterances repeat themselves with different wording to examine internal reliability. The questionnaire in- cludes an additional section describing the respondent’s socio-demographic characteristics. Assuming that some of the respondents, afraid of being identified, would skip the questionnaire’s socio-demographic section, very few items were included in this section. The questionnaire addresses three main areas. Legitimacy of the use of force (α = 0.65)—this sec- tion includes utterances like “The best way to achieve order is through use of force”; and “Use of violence protects the cop when he’s working”. Attitude towards supervision of the use of force (α = 0.76)—includes utterances like “Handing investiga- tions of cops over to the Police Investigations De- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. BLR  The Legitimacy of Using Excessive Force during Civil Policing among Israel’s Border Guard Police Officers Copyright © 2012 SciRes. BLR 19 partment hurts police work”; or “The need to inform the command about the cop’s work in the field keeps him from doing his job right”. Attitude towards the police officer’s autonomy (α = 0.62)—utterances like “Only another cop can pass judgment on a cop who uses too much force”; “Lots of times laws and rules help the bad guys and make it hard for the cops”; and “Sometimes in cop work you have to bend the rules to reach your goal”. The questionnaire was distributed among 140 Border Guard police and men and women in blue serving in the Southern Command of the Israeli Police. 80 field police officers were sampled from four police stations in the South and 60 Border Guard officers from the same re- gion. Of these, 102 filled out the questionnaires com- pletely—50 Border Guard and 52 regular police officers (the remainder chose not to fill in their sociodemographic details; therefore, their responses are not included in the study). In addition, 60 questionnaires were distributed to ordinary civilians. These were chosen randomly from a group of first-year students at a college from the same region. Table 1 reveals that males comprised 60% of all those who fully completed the questionnaires, most respon- dents were native Israelis (81%) and Sephardi (i.e., with ethnic roots in Arab countries) 67%. A comparison of the groups shows that the citizen group is younger than that of the police personnel. The highest percentage of native Israelis is among the Border Guard police; the lowest, among the civilians. Women account for the highest proportion among the civilians and for the lowest among the Border Guard. In light of the fact that the groups differ significantly in gender, age, and country of birth, we also examined whether these variables were significantly related to the level of legiti- macy ascribed in the three areas examined in the study. 3. Results Table 2 shows the frequency in percentages for the three dimensions of legitimacy of excessive force among the three groups of respondents. Table 2 reveals that among all the subjects, both po- lice officers and civilians, the use of force in policing was given a high level of legitimacy. Two thirds of the regular police officers thought that the crime rate would decline if there were fewer limitations on the use of force. The greatest support for use of force in the course of civil policing was found among Border Guard police (72%); similar percentages of support were found for field police and civilians. Over half the respondents thought the use of excessive force protects the police officer performing his duty (57% - 58%). The three groups of respondents also tended to support the claim that obeying laws intended to regulate the mat- ter of use of force in police work made that work more difficult. The highest frequency for this claim was found among Border Guard police (74%). Nearly all (94%) of the Border Guard police examined thought that supervi- sion mechanisms made police work more difficult; that is, these police personnel for the most part (86%) think the need to keep the commanders informed interferes with the operational efficiency of their missions, as compared with 38% of the regular police personnel and 33% of the civilians group who support this claim. The highest rates of support for the claim that only an- other police officer is in a position to judge an officer accused of use of excessive force were found in the Bor- der Guard group (82%), in comparison with 54% for regular police officers and 41% for civilians. Most of the Table 1. Comparison of three groups (%). Characteristics Border Guard Police n = 50 Regular Police Officers n = 52 Civilians n = 50Significance Gender (X2) p < 0.00 men 78 65 42 women 22 35 58 Country of Birth (X2) p < 0.00 Israel 90 80 65 other 10 20 35 Ethnicity (X2) p > 0.15 Sephardi 82 67 80 Ashkenazi 18 33 20 Average Age (SD) (ANOVA Test) p < 0.05 27.44 (9.09) 28.52 (6.07) 25.07 (3.38)  The Legitimacy of Using Excessive Force during Civil Policing among Israel’s Border Guard Police Officers 20 Table 2. Percentage of agreement for the use of force among the three groups. Attitude Border Guard Police Regular Police Officers Civilians Legitimacy of use of force The crime rate would decline if there were fewer limitations on the use of force. 54 75 43.10 The use of force is a legitimate part in the police work. 74 94 72 The use of excessive force protects the police officer performing his duty. 72 57.30 58.80 Compliance with laws regarding the use of force makes it difficult to cope with various situations. 74 69.20 68 The preferred way to handle disturbances is through the use of physical force. 62 85 60 Supervision of the use of force Transfer of investigations of police officers to the internal affairs department interferes with police work. 76 69.20 50 Supervision mechanisms make police work more difficult. 94 80 64.80 Command intervention in field work makes the officer’s work more difficult. 78 59.70 56.90 The need to update the commanders interferes with the operational efficiency of their missions.86 38.50 33.30 Judges’ decisions would be different if they saw what was really done. 91 75 85 Police officer’s autonomy Only another police officer can sit judgment on the use of excessive force. 82 53.80 41.20 In some cases there is no other way to handle a situation than by disregarding the law. 72 76.40 64.70 Existing laws primarily help the criminals. 92 90.40 86.30 Reporting their work hinders the police officers’ ability to perform their jobs. 80 52.90 50.90 The officer will perform his duties more effectively if he doesn’t have to worry about the legality of his actions. 75 59 46 respondents from all three groups supported the claim that it is actually the criminals who are often the benefi- ciaries of the law. 3.1. Differences between the Three Groups of Respondents Regarding the Legitimacy of the Use of Excessive Force To examine whether there are significant differences be- tween the degree of legitimacy attributed to the use of force, the need for external supervision, and police autonomy among the three groups, a one-way ANOVA was performed. There were significant differences between the re- search groups in the legitimacy accorded to the use of force in policing activity (F(2150) = 3.02, p = 0.05, η2 = 0.04). A Bonferroni analysis shows that the average le- gitimacy among regular police officers (M = 3.23, sd = 0.80) was significantly higher than among civilians (M = 2.90, sd = 0.78). At the same time, there was no signifi- cant difference between Border Guard officers (M = 3.04, sd = 0.41) and the regular police officers. 3.2. Legitimacy Attributed to External Supervisory Mechanisms A significant difference between the groups was also found regarding the level of legitimacy attributed to ex- ternal supervisory mechanisms in police work (F(2150) = 17.51, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.19). A Bonferroni analysis found that the average opposition to external supervision was significantly higher among Border Guard Police (M = 3.46, sd = 0.58), as compared with regular police (M = 2.90, sd = 0.80) or civilians (M = 2.60, sd = 0.77). 3.3. Professional Autonomy for the Police Officer The third measure dealt with the level of legitimacy ac- corded to professional autonomy for police in the field. For this measure too, the three groups differed signify- cantly from one another (F(2150) = 7.73, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.09). A Bonferroni analysis revealed that among civil- ians the average support for the claim that “only another police officer can sit in judgment on the use of excessive force” (M = 2.30, sd = 1.16) was significantly lower in Copyright © 2012 SciRes. BLR  The Legitimacy of Using Excessive Force during Civil Policing among Israel’s Border Guard Police Officers 21 comparison with that of the Border Guard Police (M = 3.20, sd = 0.72) or regular police (M = 2.80, sd = 1.22). No significant difference was found between Border Guard and regular police personnel. Examining the subjects’ attitude to the perception that “the existing laws primarily help the criminals” the re- search showed a significant difference between the three groups (F(2150) = 3.30, p > 0.05, η2 = 0.04). A Bon- ferroni analysis showed that there is a significant differ- ence between the police officers in blue (M = 4.21, sd = 0.95) and Border Guard officers (M = 3.70, sd = 1.05), but there is no significant difference between the police officers and the civilian group (M = 3.88, sd = 1.05). 3.4. Socio-Demographic Characteristics, Professional Affiliation, and Attitudes towards Excessive Force in Police Work Since significant differences appeared in some of the socio- demographic characteristics of the three groups that par- ticipated in this study, the next stage will examine whe- ther the source of the differences found in the levels of legitimacy might be the results of the differences found in the characteristics of the groups. No significant difference was found between men and women regarding the three legitimacy measures; use of force, external supervision, and professional autonomy. However, there was a significant difference between na- tive Israelis and non-native Israelis with regard to the measure of external supervision they deemed necessary (t(150) = 2.1, p < 0.05). The average opposition towards external supervision was higher among native Israelis (M = 3.04, sd = 0.78), in comparison with non-natives (M = 2.70, sd = 0.79). There was also a significant difference regarding the degree of legitimacy for the use of exces- sive force in police work between Ashkenazi Jews (i.e., Jews of central or eastern European descent) and Sephardi Jews (t(150) = 2.1, p < 0.05). Ashkenazi Jews were more inclined to condone police violence (M = 3.27, sd = 0.72) than Sephardi Jews (M = 2.99, sd = 0.65). At the same time, it should be noted that there was no significant dif- ference between the groups with respect to the distribu- tion of the ethnic origin variable. Noting these differences, the next stage examined whether the police and the civilians had different atti- tudes toward the three measures, controlling for gender, age, and birth country, using a one-way ANOVA. This analysis showed that even controlling for the differences in socio-demographic characteristics of the three research groups, the differences in attitudes between Border Guard officers, ordinary police officers and civilians in the three measures examined remained. There was a sig- nificant difference between the groups regarding the le- gitimacy of resorting to force in civil policing (F(2139) = 2.90, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.04), and in attitudes towards the need for external supervision of the work of the police in general and of the use of force in police work in particu- lar (F(2139) = 14.68, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.174). Also pre- served was the significant difference between the three groups in the legitimacy they accorded to the police offi- cer’s professional autonomy and to the perception that the legal system interferes with policing (F(2139) = 5.12, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.06). 3.5. Relationships between Various Attitudes towards Use of Force in Policing Having described the attitudes of the subjects in the three groups towards the three measures of legitimacy towards excessive police force, the research also examined the relationships between the attitude’s three components and between them and the subjects’ age. Table 3 reveals that the older the police officer or the citizen, the lower his or her support for use of excessive force, and for strengthening the professional autonomy of the police officer in the field. The findings show that subjects who favored increasing the police professional autonomy also expressed the greatest opposition towards external supervisory mechanisms, referring incidences to the Department of Police Investigation under the author- ity of the Ministry of Justice, etc. There was also a sig- nificant positive correlation between support of profes- sional autonomy for police and the legitimacy accorded to the use of excessive force in civilian policing situa- tions. A significant positive correlation was also found between the legitimacy towards excessive force and op- position to the external supervision mechanisms whose function, among other things, is to control and regulate the use of excessive force in policing activities. 4. Discussion For over six decades the Israeli society has endured a very high level of security threats and one of the main bodies combating those threats is the police force. The involvement of police units such as the Border Guard in fighting terror, and the constant threat on Israeli society might explain the high level of support for the use of excessive force in civil policing activities found in this Table 3. Correlation between age and various attitudes to- wards use of force. Age Legitimacy Supervision Legitimacy −0.24** Supervision 0.13 0.58** Autonomy −0.18* 0.66** 0.71** **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. BLR  The Legitimacy of Using Excessive Force during Civil Policing among Israel’s Border Guard Police Officers 22 study among police and civilians alike. The formal mechanisms developed in Israeli society to regulate and supervise the use of excessive force by police are seen by the vast majority of the police officers in this study and by at least half of the civilians, as interfering with the officer’s ability to do his job effectively. Nearly three- fourths of all the respondents in this study agree with the claim that obeying the laws limiting the use of force re- stricts the police officers’ ability to fulfill their police tasks effectively. It seems that our data shows support with the basic assumptions of the “crime control model”, which considers efficiency and economy as the key val- ues in law enforcement, rather then the “due process model”, which elevates the values of credibility and safeguarding civil rights (Lernau, [28]). The “crime con- trol model” enjoys greater support from the research subjects in general and police personnel in particular. The three values examined in this research—legitimacy of use of excessive force during police activity, oppose- tion to external supervision for police activities, and the granting of professional autonomy to the police—show a significant positive correlation. Together they reflect a professional sub-culture and intra-organizational norms that prioritize crime-fighting and the use of excessive and violence as legitimate and efficient means, to be left to the discretion of the officer in the field (Goldsmith, [17]; Amir, [14]). Comparison between the attitudes of the ordinary police officers and those of the Border Guard Police officers shows that the professional affiliation of units working at the juncture where civilian policing meets military defense results in the greatest support for the Crime Control Model. More than any of the other respondents, the Border Guard officers tended to view the laws and regulations limiting the use of force as an obstacle to be bypassed in order to effectively perform their job. These findings augment the previous findings of Carmeli and Shamir [15], indicating a high level of legitimacy among Border Guard police for the use of force in civilian policing. Although, civilians gave the least legitimacy to the use of excessive during civil policing, nevertheless half the civilians who took part in the study expressed support for the use of physical force against citizens. The use of physical force is also viewed by a considerable propor- tion of the civilians as necessary for efficient crime- fighting, while the need for supervision and restrictions of excessive use of force, a derivative of the due process model, is mainly perceived as an expression of how cut off the decision-makers are from the bleak reality in the field. About half of the civilians think the need to worry about the legality of the use of force prevents police of- ficers from effectively doing their job. Carmeli and Shamir [15] note that three hindrances to effective crime- fighting exist in Israel: the shortage of tools for dealing with crime, inadequate backing by the courts and the police senior command, and the divided opinions among police personnel as to the limits of use of force. These hindrances combine to reinforce support even for force that is excessive to cope with crime. The prevalent assumption that men are more militant than women (Kamir, [30]) was not borne out by this study. In all measures examined, there were no differ- ences found between men and women in the degree of legitimacy for the use of force or in the perception of the law and the supervisory mechanisms deriving from it as interfering with crime-fighting and hampering the ability of the police to do their job properly. 5. Conclusions The broadening of the Israel Police’s ethical code in 2004 and the various criticisms of the use of excessive force in policing during the past decade (State Comptrol- ler, [5]) do not seem to have fundamentally changed how police in general, and particularly those of the Border Guard, relate to the use of force. Considering the rela- tively broad support found among police and civilians for use of force and violence, the ethical code is likely to continue to serve nothing more than a declarative pur- pose. A scrutiny of the fluctuations between the different forces shaping the professional culture of the police in Israel and the personal and professional attitudes of the police who operate within this culture reveals that the belligerent ethos and the increasing involvement of po- lice units in the fight against terror attacks Are, to a great extent, shaping the perceptions of the police. The atti- tudes of the police, especially those of the Border Guard, who are fighting a constant battle against security threats alongside the war against crime, are to a great extent in- capacitating the basic assumptions of the community policing model, which transforms the civilian from po- tential suspect to partner in the solution of problems. These attitudes are also greatly restricting the power of the external and internal supervision mechanisms to ef- fectively supervise the use of unreasonable force in the activities of civilian policing. From the findings of this paper and other works re- garding the use of excessive force by police officers (such as Gimshi, [3]; Yechezkeli, Shalev & livni, [31]), we concluded that in order for the ethical code to become feasible and operable, it is necessary to anchor it to the disciplinary regulations and to create a system of internal laws within the organization. To avoid a situation in which the ethical code regulating use of force remains nothing more than an ideological notion, it is necessary to promote public and organizational discussion regard- ing the use of excessive force, with punitive ramifica- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. BLR  The Legitimacy of Using Excessive Force during Civil Policing among Israel’s Border Guard Police Officers Copyright © 2012 SciRes. BLR 23 tions for situations in which police resort to inappropriate use of force. REFERENCES [1] R. Reiner, “The Politics of the Police,” 4th Edition, Ox- ford University Press, Oxford, 2010. [2] E. Bittner, “The Capacity to Use Force as the Core of the Police Role,” In: V. E. Kappeler, Ed., Police and Society, Waveland Press, Long Grove, 2006, pp. 61-68. [3] D. Gimshi, “Criminal Justice System—Law Enforcement in a Democratic State,” Peles Publishing, Rishon Lezion, 2007. [4] J. H. Skolnick and J. J. Fayfe, “Above the Law: Police and the Excessive Use of Force,” Free Press, New York, 1993. [5] The State Comptroller, “The Systematic Treatment of Complaints about Violence and Improper Behavior of Police Officers,” State Comptroller Annual Report, New York, 2005. [6] S. Werner and M. Tsemach, “The Code of Ethics and Law Enforcement System in Israel and around the World,” The Security Office, Jerusalem, 2006. [7] D. Bayley and D. Weisburd, “To Protect and to Serve: Policing in an Age of Terrorism,” Springer Verlag, New York, 2009. [8] D. Weisburd and A. Braga, “Police Innovation,” Cam- bridge University Press, New York, 2006. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511489334 [9] S. Herzog, “Militarization and Demilitarization Processes in the Israeli and American Police Forces: Organizational and Social Aspects,” Policing and Society, Vol. 11, No. 2, 2001, pp. 181-208. doi:10.1080/10439463.2001.9964861 [10] D. Weisburd, G. Jonathan and S. Perry, “The Israeli Mo- del for Policing Terrorism,” Criminal Justice and Behav- ior, Vol. 36, No. 12, 2009, pp. 1259-1278. doi:10.1177/0093854809345597 [11] G. Jonathan, “Police Involvement in Counter-Terrorism and Public Attitudes towards the Police in Israel: 1998- 2007,” British Journal of Criminology, Vol. 50, No. 4, 2010, pp. 748-771. doi:10.1093/bjc/azp044 [12] A. Braga and D. Weisburd, “Problem Oriented Policing: The Disconnected between Principles and Practice,” In: D. Weisburd and A. Braga, Eds., Police Innovation, Cam- bridge University Press, New York, 2006, pp. 133-152. [13] L. H. Robert and L. F. Travis, “Policing in America: A Balance of Forces,” Macmillan, New York, 1994. [14] M. Amir, “Using Force in the Law Enforcement System: Police Violent Behavior—People, Situations and Organi- zation,” The Hebrew University, Jerusalem, 1998. [15] A. Carmeli and N. Shamir, “Research Report: Police Violence against Civilians,” The Security Office, Jerusa- lem, 2000. [16] J. W. E. Sheptycki, “In Search of Transnational Policing: Towards a Sociology of Global Policing,” Ashgate Pub- lishing, Aldershot, 2002. [17] A. Goldsmith, “Policing and Law Enforcement,” In: A. Goldsmith, M. Israel and K. Daly, Eds., Crime and Jus- tice: A Guide to Criminology, 3rd Edition, Law Book Company, Pyrmont, 2006, pp. 283-300. [18] S. Walker and C. M. Katz, “The Police in America,” 4th Edition, McGraw-Hill, Boston, 2002. [19] J. Fuller, “Criminal Justice: Mainstream and Crosscur- rents,” Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, 2006. [20] J. S. Dempsey and L. S. Forst, “Introduction to Policing,” 3rd Edition, Thomson/Wadsworth, Belmont, 2005. [21] J. H. Skolnick, “Justice without Trail: Law Enforcement in Democratic Society,” John Wiley & Son, New York, 1996. [22] W. Skogan, “The Promise of Community Policing,” In: D. Weisburd and A. Braga, Eds., Police Innovation: Con- trasting Perspectives, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2006. [23] D. Weisbord, O. Shalev and M. Amir, “Community Po- licing in Israel: Resistance and Change,” Policing: An In- ternational Journal of Police Strategies and Management, Vol. 25, No. 1, 2002, pp. 80-109. [24] Crank, “Understanding Police Culture,” Anderson Pub- lishing, Cincinnati, 1998. [25] B. Forst, “Errors of Justice: Nature, Sources and Reme- dies,” Cambridge University Press, New York, 2004. [26] B. Ekenvall, “Police Attitudes towards Fellow Officers’ Misconducts: The Sweedish Case and a Comparison with the USA and Croatia,” Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention, Vol. 13, No. 2, 2002, pp. 210-232. [27] H. Packer, “The Limit of the Criminal Sanction,” Stan- ford University Press, Stanford, 1968. [28] H. Larnau, “Law Reforms in Detention for Investigative Purposes,” Doctoral Thesis, Hebrew University, Jerusa- lem, 2001. [29] R. Worden, “Situational and Attitudinal Explanations of Police Behavior: A Theoretical Reappraisal and Empirical Assessment,” Law and Society Review, Vol. 23, No. 4, 1989, pp. 667-711. doi:10.2307/3053852 [30] A. Kamir, “Feminism, Rights and Law,” The Security Office, Jerusalem, 2002. [31] P. Yechezkeli, A. Shalev and A. livni, “Ethical Code in the Police Administration,” Management, Vol. 7, No. 1, 1998, pp. 14-18.

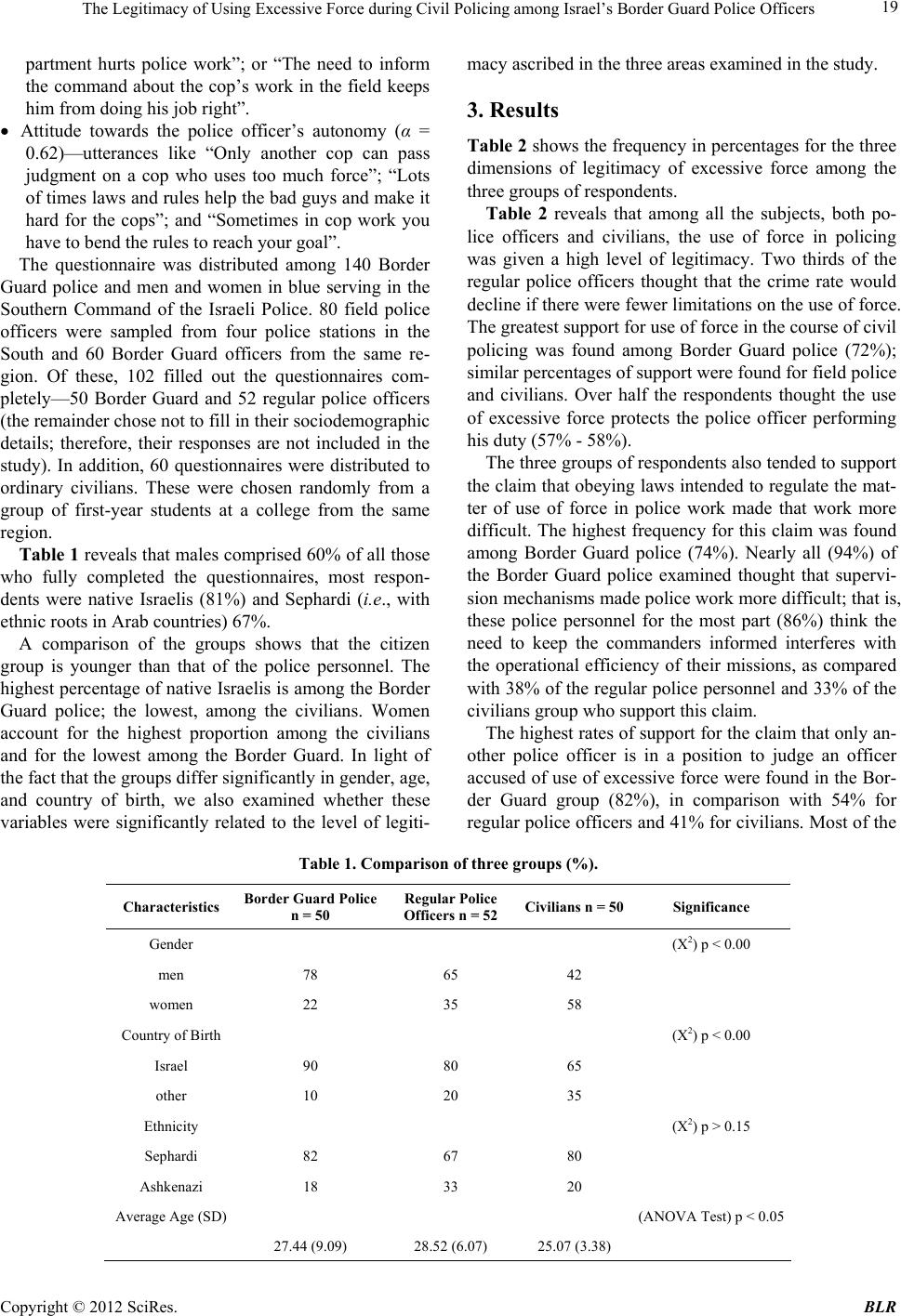

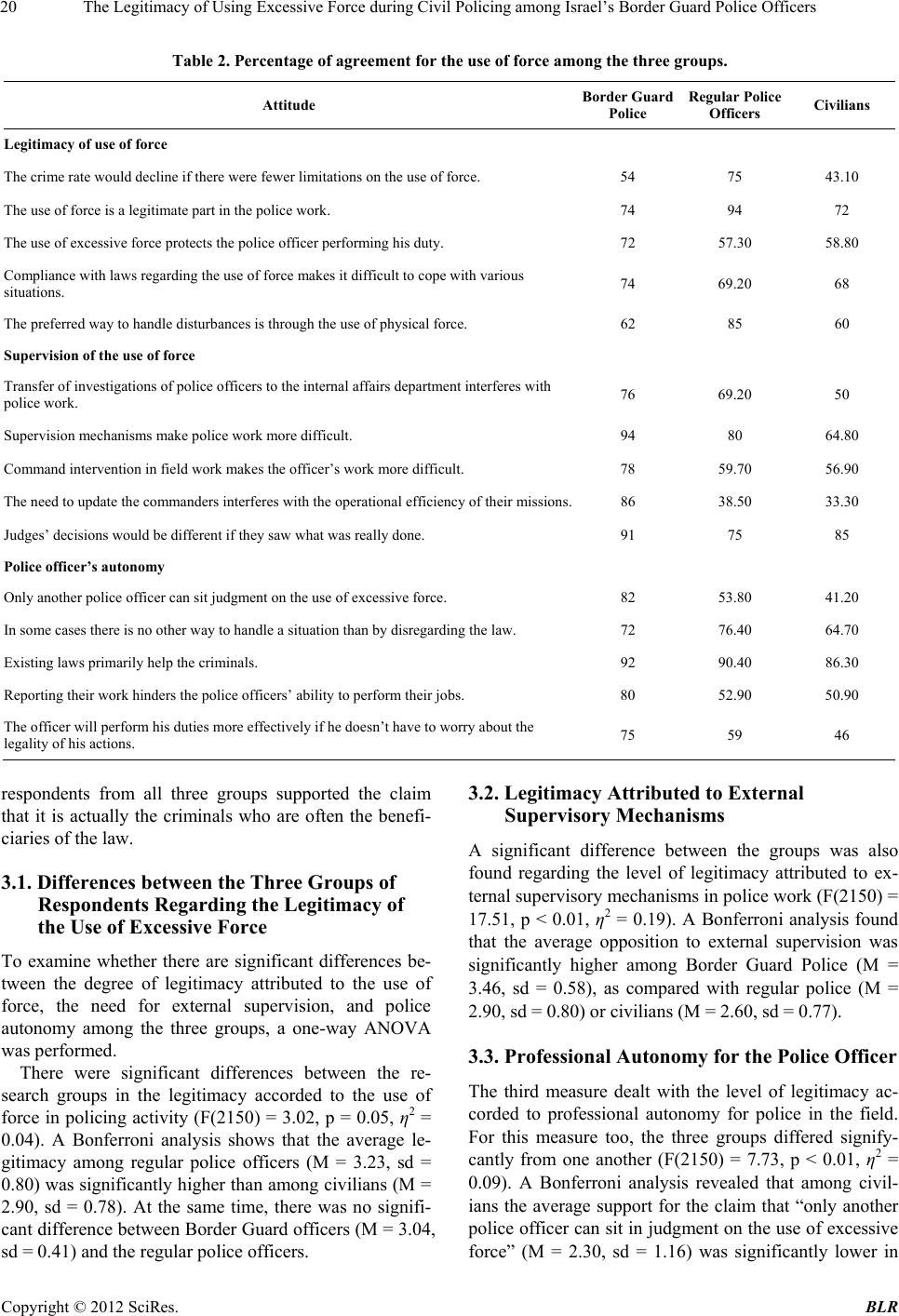

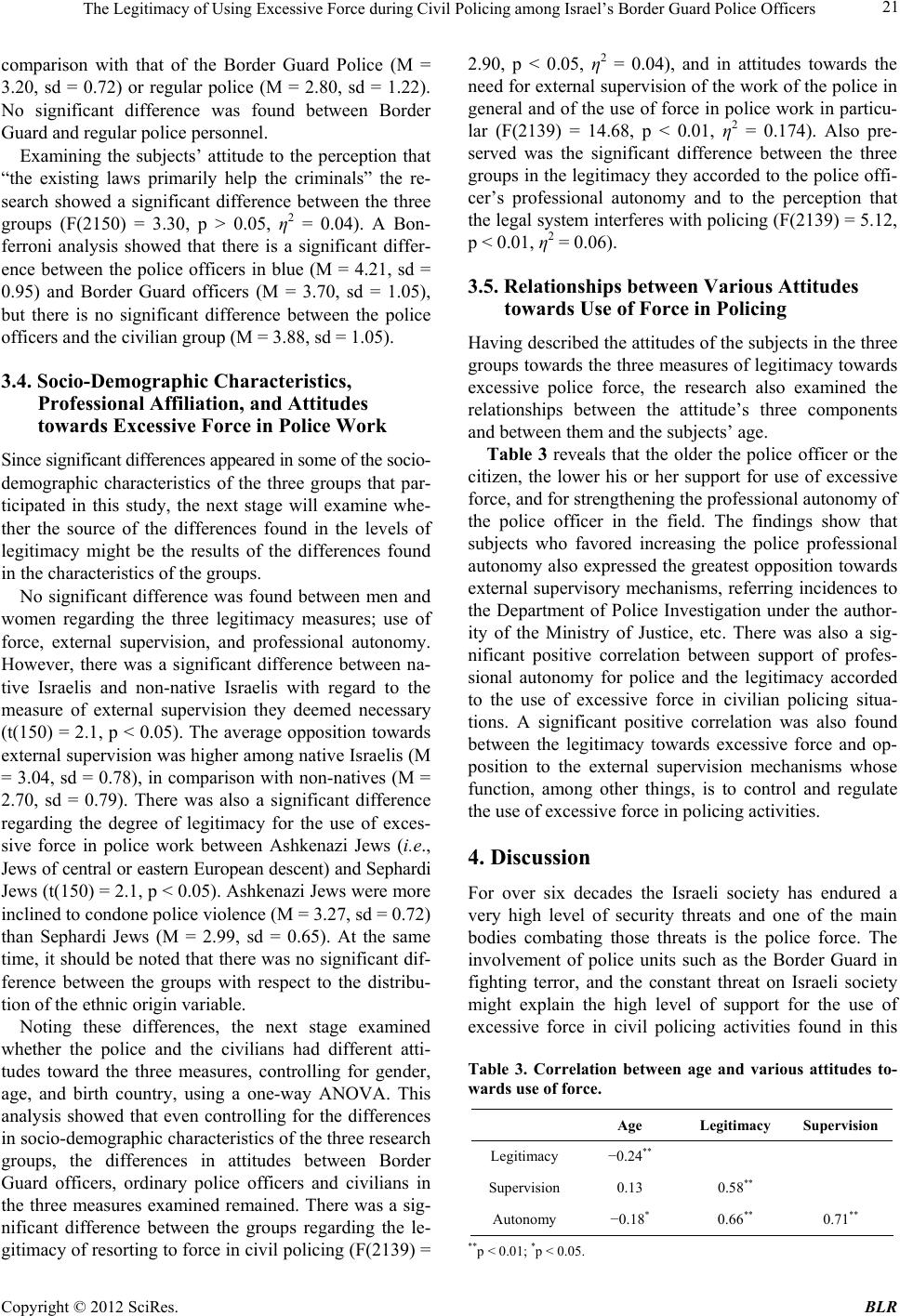

|