Health

Vol.5 No.9(2013), Article ID:36913,8 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2013.59202

Birth preparedness and complication readiness among postnatal mothers in Malawi

![]()

1Salima District Hospital, Salima, Malawi

2Research Directorate, Kamuzu College of Nursing, Lilongwe, Malawi; *Corresponding Author: shinyashishvarghese@gmail.com

3Office of the Dean of Faculty, Kamuzu College of Nursing, Lilongwe, Malawi

4Georgetown University, Washington DC, USA

Copyright © 2013 Alliet Kupatsa Botha et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 16 April 2013; revised 17 May 2013; accepted 25 June 2013

Keywords: Birth preparedness; complication readiness; danger signs of pregnancy; antenatal care education; postpartum period; maternal and neonatal mortalities

ABSTRACT

This study was conducted to assess birth preparedness and complication readiness among postnatal mothers at Khombedza Health Centre in Salima District, Malawi. The study design was descriptive cross sectional and utilized qualitative data collection and analysis method on a random sample of 15 postnatal mothers. A semi structured questionnaire was used to assess birth preparedness and complication readiness among the postnatal mothers during their most recent pregnancy and child birth. The findings indicate that overall, all the mothers had attended antenatal care and were aware of the importance of seeking health facility delivery. The mothers were also conversant with the items to bring with them during labour and delivery. Results further show that the participants had some knowledge of danger signs during postpartum and also for the new born baby but had limited knowledge of danger signs during antenatal, labour and delivery. Although the mothers had planned to deliver at the hospital, they did not save money for transport. There is therefore a need to strengthen antenatal care education on birth preparedness and complication readiness. Such knowledge would assist pregnant mothers to identify danger signs during antenatal, labour and delivery and therefore seek emergency obstetric care on time to minimize maternal and neonatal mortalities.

1. INTRODUCTION

High rates of maternal morbidity and mortality remain a major public-health challenge in Malawi. The majority of maternal deaths occur during labor, delivery, and within the 24 hour postpartum period [1]. Every day, around 1500 women die worldwide from complications related to pregnancy and childbirth [2]. The World Health Organization reported 368,000 deaths in 2009 out of which 99% occurred in developing countries with sub-Sahara African countries contributing 57% of the deaths [2]. In Africa, apart from medical causes, there are numerous interrelated socio-cultural factors which delay care-seeking and thereby contribute to these deaths. For every 100,000 live births in Malawi, approximately 675 women die from pregnancy-related complications and 31 neonates die out of every 1000 live births [3]. Some of the factors that contribute to the high maternal and neonatal mortality deaths include delays in making the decision to seek care and arriving at the health facility late [4].

Birth preparedness and complication readiness (BP/CR) are interventions designed to address the delays by encouraging pregnant women, their families, and communities to effectively plan for births and prepare for emergencies if they occur. Results of studies that were conducted in rural areas of some developing countries such as Nepal, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, and India show that promoting BP/CR improves preventive behavior and knowledge of mothers about danger signs thereby leading to improvement in care-seeking during obstetric emergency [5]. Malawi has implemented several strategies that aim at reducing the high maternal and neonatal mortality ratios [6]. The Reproductive Health and Sexual Rights (RHSR) policy of 2002, for example, contains guidelines for birth preparedness and complication readiness. Other documents include the integrated performance standards for RH, the essential health package of 2004, and the road map for accelerating the reduction of maternal mortality in 2006. These policies emphasize the improvement of the quality of maternal and neonatal services to accelerate the attainment of MDGs 4 and 5 [6]. Furthermore, these policy documents, standards and guidelines emphasize the provision of quality basic obstetric care to pregnant women and care to neonates in rural areas of the country in the designated Basic Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care (BEmONC) facilities.

Antenatal care (ANC) coverage is exceptionally high in Malawi and 94% of pregnant women attend antenatal care at least once during pregnancy [3]. However, despite the high ANC utilisation, maternal mortality ratio remains very high. The level of knowledge regarding danger signs of pregnancy in Malawi is very low [1]. In a study by Guebbels, [1] only 15% of pregnant women recognised excessive bleeding as a danger sign of pregnancy. The other danger signs of pregnancy such as sepsis and fever were completely unknown to the pregnant mothers. The pregnant women’s failure to recognize and prepare for danger signs of pregnancy suggests that the women do not seek timely access to emergency obstetric care, when need arises, hence causing the high maternal mortality ratios. Therefore, the maternal and neonatal ratios could be reduced if pregnant women knew and prepared well for their deliveries and sought health facility assistance immediately the danger signs appear.

Khombedza health centre is one of the government health facilities that were designated to provide BEmONC services to rural women and neonates residing in the catchment area of the facility in Salima district. Birth preparedness and complication readiness are one of the topics which are supposed to be taught to the women during antenatal care. However, studies on the assessment of birth preparedness and complication readiness among the women attending antenatal care (ANC) at the facility are scarce. Therefore, this study was conducted to assess the comprehension of birth preparedness and complication readiness among postnatal mothers that attended antenatal care clinics at the Khombedza Health Centre.

2. METHODS

2.1. Design

The study design was descriptive, cross-sectional and utilized qualitative data collection and analysis method to assess birth preparedness and complication readiness among postpartum mothers at Khombedza health centre during their most recent labour and delivery. The crosssectional design was used because the participants were selected during one period for data collection [7].

2.2. Setting

The study was conducted at Khombedza Health Centre in Salima District, Central Region of Malawi. The facility is one of the health centres which provide BEmNOC services in the district. The facility serves a population of 151,535 out of which 11,852 are women of child bearing age [3]. Unpublished data at the facility show that the facility conducts 2577 deliveries per year and 387 of the deliveries are expected to require emergency obstetric care. The site was chosen because it conducts more deliveries than any other health centre in the district.

2.3. Sample

Data saturation was reached after interviewing 15 randomly selected postpartum mothers about their birth preparedness and complication readiness during their most recent labour and delivery. All the participants that met the inclusion criteria consented to participate in the study.

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The study recruited women who delivered a live infant, made at least one antenatal care visit during their most recent pregnancy, and communicated in English or the vernacular language. Women who did not attend any antenatal care during their most recent pregnancy, were sick or mentally disturbed at the time of study, or could not speak or communicate in English or vernacular language were excluded from the study.

2.5. Data Collection

A semi-structured interview guide was administered to the participants through in-depth face to face interviews. Data was collected by the senior author who is also a state registered nurse—midwife and the questionnaire facilitated a two-way communication between the researcher and the participants. The interviews were conducted in a private room within the health facility and each interview was audio taped. During the interviews demographic data was collected from each participant. The demographic data included; age, marital status, number of children, tribe, religion, occupation, income level and highest education level for each participant. Regarding health seeking behaviour, information was sought from the participants regarding the following; description of the way the decision was made to seek facility delivery, the distance from home to the facility, the mode of transport used, knowledge of birth preparedness and complication readiness that was acquired during antenatal care education. The knowledge was assessed in terms of number of times the participants attended ANC before delivery, information that was provided during the ANC regarding; the best place for delivery, danger signs during pregnancy, birth and delivery and, postnatal period, prior arrangements for blood donor, transport to the facility and items to be prepared in advance for the new born baby. Finally, the participants were asked about their perception of the care they received at the facility during their labour and delivery.

2.6. Data Analysis

Data was analyzed manually using content analysis. This analysis involved reading repeatedly the interview transcripts several times, organising, labelling and coding of variables into categories. Similar responses were grouped together into themes and the major themes and sub themes were identified. Exemplars were selected to represent each theme and sub theme. The themes and subthemes are presented as results of the study.

2.7. Trustworthiness

Four criteria [8] for enhancing rigor in qualitative research (credibility, confirmability, dependability, and transferability) were used to ensure trustworthiness of the results. The qualitative data was validated to ensure confirmability [9]. Credibility was guaranteed by using the member checking approach in which the researchers referred back to 9 selected participants to verify the data and interpretation of the findings. Transferability was established through the collection of data that included field notes, together with a rich mix of participants’ narrations. Confirmability was ensured through the process of bracketing where by all previous knowledge, beliefs and common understanding about birth preparedness and labour and birth complication readiness behaviours among women in Malawi were set aside.

2.8. Ethical Consideration

The study was approved by the College of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee (COMREC). Permission to access Khombedza health Centre facility was obtained from the Salima District Health Officer. Participants were informed in detail about the study and an informed consent was obtained before interviewing the participants.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

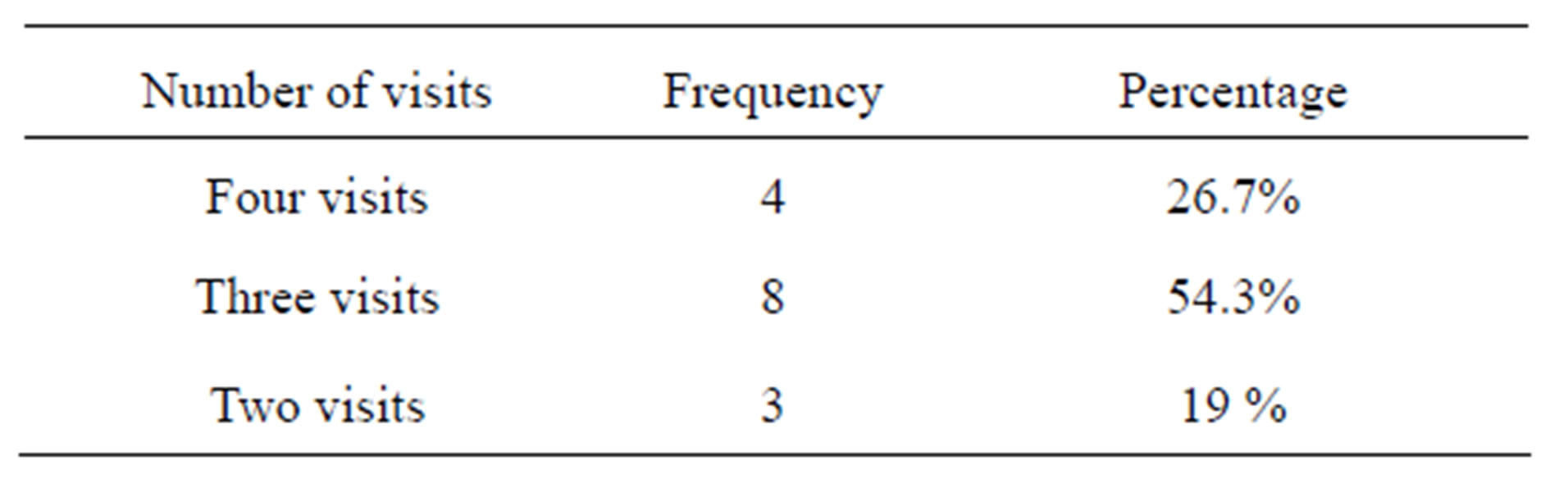

A total of 15 postnatal mothers who had delivered within the past 12 hours participated in the study. Most of the participants (53.3%, n = 8) were aged between 20 and 35 years, with a mean age of 25 years and a range of 18 to 40 years. Regarding education qualification, most of the participants (73%, n = 11) attended school but the majority (66.6%, n = 10) only attended up to primary school level. As a result, most of them (46.7%) were housewives who were mainly engaged in farming. The number of ANC visits among the participants is shown in table 1. Most of the participants (81%, n = 12) attended the minimum 3 visits as recommended by the focused antenatal care guidelines.

3.2. Theme

The narrations of the participants have been categorized into one main theme; coverage of birth preparedness and complication readiness during antenatal care education. Two sub-themes which emerged were: Elements of BP/CR that were known by participants and areas of BP/CR in which participants had limited knowledge.

3.3. Elements of BP/CR That Were Known by Participants

The narrations of the participants show that they were very conversant with routine checks such as physical examinations that were conducted on them and the receiving of prescribed medication from the health workers. In addition, the participants were conversant with the importance of good nutrition, exercises and rest during pregnancy. Regarding elements of BP/CR, the participants were more knowledgeable with the place for safe delivery, items to bring to the facility during labour and delivery and danger signs during the postnatal period for the mother and the baby.

3.4. Examination and Medication

All the participants explained that they were examined during each antenatal visit and medication was given or administered when necessary. Participant # 12 shared her experience as follows:

“When I attended antenatal care clinic, she (the health worker) examined me and told me that I needed some medication. They gave me the medicine which I took and kept some for taking at home. After the medication, they gave me the next day of my antenatal care visit.”

3.5. Good Nutrition

The importance of good nutrition to a pregnant woman

Table 1. Number of antenatal visits made by the participants during their pregnancies.

was emphasized during ANC education and all the participants had knowledge on the importance of good nutrition to promote positive birth outcomes.

“I remember we were told that as mothers we needed to eat all the six groups of food, because good nutrition is important for positive childbirth outcomes.” Participant #11.

3.6. Exercises during Pregnancy

The need for a pregnant woman to exercise regularly was mentioned by 8 of the 15 participants. They were told that during pregnancy, a woman should be physically fit and hence exercises were very important for positive birth outcomes. Participant # 1 narrated as follows:

“I was told that a pregnant women needs to do some exercises regularly. Exercises strengthen the body and a pregnant woman becomes strong to withstand labour and delivery.”

Of the 8 participants who narrated on the importance of exercises during pregnancy, 6 mentioned that they were also advised to rest. This point was shared by participant #5 as follows:

“The health workers also advised me to create ample time for rest. They said that we should reduce our workload so that we have ample time for rest. Physical exhaustion is not good for a pregnant woman because it weakens the body.”

3.7. Place of Delivery

All the participants indicated that they were told to deliver at the hospital. The participants narrated that they were told not to deliver at home or at the Traditional Birth Attendant’s places but at the hospital where they could be rendered quality of care during their labour and delivery. This point was explained by participant #10 as follows:

“I was told to deliver not at home or at the TBA’s place but at the hospital because at the hospital there is skilled personnel and equipment which ensures safe delivery.”

3.8. Items Needed during and after Delivery

All participants narrated that they were told to prepare in advance to bring items that are needed during and after delivery. This point was shared by participants #8 as follows:

“The health workers told me that when coming for delivery I needed to bring razorblade for cutting umbilical cord, thread for tying, clothes and basin for bathing. She said that these items were very important and I should never forget to bring them when coming for delivery Participant #10.”

Participants #9 also explained that health workers emphasized during antenatal care education about the need for advance preparation for the items that are required by the baby after birth and the mother after giving birth as follows:

“I was told to prepare well and bring a number of items when coming for delivery. The items were: wrapper for the baby and, pads, new half petticoat and pants for myself. They (Health workers) emphasized that I will need these items while here at the hospital.”

3.9. Danger Signs during the Postnatal Period

The majority (13 out of 15) understood danger signs during postpartum and mentioned the following correct danger signs; retained placenta, excessive bleeding, heart palpitations, dizziness and fever. Excessive bleeding was mentioned by all participants. Participant #7 gave the following explanation:

“Some of the danger signs include retained placenta, I did not feel well until it was removed. Another danger sign I know is excessive bleeding. When a woman bleeds continuously after giving birth it means that something is wrong and she needs to see a doctor immediately.”

3.10. Danger Signs for Newborn Babies

Knowledge about danger signs for the new born babies were known by most (14 out of 15) participants. The women were able to mention jaundice, bleeding from the cord, continuous cry, refusing to breast feed, not able to pass stool and urine, twitching, convulsions and fever. Some mothers (6 out of 15) were able to mention more than three danger signs. Participant #2 made the following narration;

“When the baby is born, some of the danger signs could be convulsions, twitching, refusing to breast feed and shivering if you see all these signs you have to report to the doctor.”

Despite the high level of knowledge among the mothers regarding danger signs for the newborn baby, some women mixed the correct danger signs with incorrect ones. For example some women (8 out of 15) included abdominal pains, coughing, yawning, tetanus and shivering as danger signs for the baby.

3.11. Elements of BP/CR in Which Participants Had Limited Knowledge

The knowledge of birth preparedness and complication readiness during antenatal was very low. A total of 10 out of 15 postnatal mothers reported that the midwives did not provide them with any information or advice about birth preparedness and complication readiness during antenatal. Participant #4 shared as follows:

“She (the health worker) did not tell me anything concerning birth preparedness and complication readiness during the antenatal period. She only told me to come here at the hospital on 4 July 2011, because that was my next scheduled antenatal care visit. May be she did not tell me because she thought that there was still some time and she was going to tell me during my last visit, I mean on the 4th of July”—participant #4.

Generally participants did not know all the five elements of birth preparedness and complication readiness. The narrations of the participants suggest that the place for delivery and items needed for safe delivery were the only elements that were well-known. There was however limited knowledge regarding other elements such as transport arrangements for delivery, advance identification of a blood donor and identification of signs of obstetric complications.

3.12. Transport Arrangements for Delivery

The item on advance transport arrangement was known by very few (4 out of 15) participants. In addition, some participants (3 out of 4) who had saved money for transportation had used the money for other purposes other than hiring transport to the hospital. Participant # 3 narrated her experience as follows:

“I was told by the midwife to save money little by little, and in addition my husband gave me some money which I used to save as well. This money was supposed to be used for hiring transport in case labour starts and I do not have money. Then I could take the bicycle taxi to the hospital. This is important because one could not foretell if the husband would be around during the time of labour. As a result I used to save the money but it just happened that there were other pressing needs at home which compelled me to use the money. In the end I used the money before labour started.”

Some participants (5 out of 15) indicated that they saved some money not for transport during labour but celebrating the birth of the baby. “I saved money in order to prepare for the celebrations of the baby after giving birth.”—Participant #8.

Results further show that women who had a means of transport within the home did not bother to save money for transport to be used during labour because they thought that their spouses would escort them to the hospital. However, for 2 of the participants, their bicycles were not readily available when their labour started. Participant #3 shared her experience as follows:

“My husband was not around he went to the lake to buy fish when labour started. I waited in vain for him to return so that he should escort me to the hospital. After noticing that he was going to delay, I hired a bicycle and came here at the hospital. I wish I had saved money for hiring a bicycle despite having one in the home.

3.13. Identification of a Blood Donor

One of the important components of BP/CR is identification of a blood donor. Participants gave different answers regarding what they knew about blood donor identification. Few of the participants (5 out of 15) indicated that they knew that they needed to identify a blood donor. Participant #4 narrated as follows:

“About a blood donor, the health worker said that I should come with a man who was going to donate blood and the man should be nearby because sometimes I might need the blood.

There were 3 participants who identified blood donors but despite making advance arrangements, their blood donors were not available during the time of labour and delivery.

“I knew I had to bring a blood donor and my brother agreed but when labour started he was not around to donate blood in case I needed some.”—Participant #5.

3.14. Knowledge of the Danger Signs of Obstetric Complications

Results show that few participants (7 out of 15) knew about key danger signs during antenatal, labour and delivery.

3.15. Danger Signs during Antenatal Period

Few participants (4 out of 15) were able to articulate some of the danger signs such as excessive bleeding, convulsions, heart palpitations, and dizziness. There were 7 participants who were not able to identify any obstetric danger sign and 4 participants wrongly mentioned abdominal pains, general body pains, being HIV positive and oedema of the legs to be danger signs of pregnancy. Participant #2 narrated wrong danger signs of pregnancy as follows;

“Another danger sign is that sometimes you may be tested HIV positive. Therefore you receive some help when you came to the hospital.”

3.16. Danger Signs during Labour and Delivery

Most of the danger signs during labour and delivery were not known to the participants. Majority of the participants (12 out of 15) mistook the signs of labour such as draining of liquor, backache, lower abdominal pains, oedema of the legs and general body pains for danger signs of labour and delivery. There were 6 participants who could not mention any one danger sign of labour and delivery. Participant #15 explained that she did not know any danger sign of labour and delivery because she was not taught.

“As for me I was not told anything about the danger signs of labour and delivery. In addition, I was not given any particular advice concerning the danger signs during all the three antenatal care visits I made.”

4. DISCUSSION

Antenatal care clinics in Malawi provide surveillance for pregnant women and their babies. Preventive care mea-sures include immunization with Tetanus Toxoid vaccine (TTV), screening for sexually transmitted infections, (including syphilis and HIV), provision of malaria prophylaxis and early detection of anemia and pre-eclampsia. Focused antenatal care (FANC) is a widely used strategy to improve the health of pregnant women and encourage skilled care during childbirth [10]. The antenatal period provides important opportunities for reaching pregnant women with a number of quality interventions that are vital to improve maternal and child health [11]. In 2001, the Ministry of Health in Malawi adopted recommendations from WHO to introduce a FANC approach to improve the quality of ANC services. According to WHO guidelines, FANC entails four antenatal care visits in normal pregnancy. This approach requires health facilities to have adequate infrastructure, essential equipment, drugs and laboratory supplies [12]. Additionally, clinical skills of the health care provider are required to conduct ANC examinations, performing laboratory investigations, providing drugs and immunizations and pro-viding health education and counseling.

Results show that all the postnatal mothers that participated in the study had attended antenatal care and gave birth with a skilled birth attendant. Participants in this study had an average of three ANC visits during their pregnancy. This is high as compared to unpublished data for the district which indicated that pregnant women, who sought antenatal care, received an average of 2 antenatal visits during their pregnancy [13]. During antenatal care education, women and their families are supposed to be informed about danger signs and symptoms and about the risks of labour and delivery. The findings of this study did not support this premise as most of the mothers were not conversant with birth preparedness and complication readiness during antenatal period. There is therefore a need to strengthen antenatal care education to ensure that women properly understand about these danger signs.

Results indicate that some midwives in this study did not routinely provide women with information on birth preparedness and complication readiness as part of ANC, especially the elements concerning antenatal, labour and delivery. Instead the women were well informed about the importance of nutrition and rest, which is still part of ANC education. Educating mothers on BP/CR is an integral component of antenatal education hence the women should as well have been well informed about this element. Lack of knowledge on these elements may lead to delay in seeking care from skilled attendants to manage obstetric complications when they occur thereby leading to maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality. These results are similar with those reported from India [14] where women who did not have adequate and appropriate information about pregnancy and child birth were ill equipped to make choices that could contribute to their own well being. The quality of information given during pregnancy ultimately affects maternal and neonatal health.

Other studies [15] have shown that access to information through health workers and modern media made women become knowledgeable about delivery risks and availability of services. In Malawi, many women have limited access to radios or mass media and this is true for Salima district where the study was conducted. Therefore, health workers remain the only source of information during counselling and education in the prenatal period and during ANC. This information is crucial in building the knowledge and self-confidence of women as they prepare to give birth.

The study findings indicate that participants had knowledge about a place of delivery and what to specifically prepare for the baby. This information was consistent across all the participants. What varied was the lack of timely preparation as some were preparing before labour while some were buying the items after they had already delivered. Place of delivery identification is very important especially in this setting where the main means to get a skilled provider is to deliver at a health facility. Women who planned facility delivery made advance arrangements for transport. These results agree with those reported by Hiluf and Fantahun [16] that mothers who received advice about where to give birth saved money for transport and were well prepared for birth and its complication. However, some women in this study did not save money for transport in the case of an emergency. Unavailability of funds for emergencies may be attributed to ignorance on the importance of birth preparedness and complication readiness as many participants may not have been informed adequately or understood the importance of saving money for transport. The ignorance could also be attributed to the low education level of the women in this study as most of them were either housewives or business women due to low education.

Identification of appropriate and compatible blood donors and their availability in case of an emergency is life saving, especially in facilities where blood is scarce. Making arrangements for blood donors is also important because women giving birth may need blood transfusions in the event of haemorrhage or caesarean section. Some studies [17] have identified unavailability of blood to be a barrier to receiving adequate and appropriate treatment during an emergency. Blood donor systems at the community level can help overcome problems related with access to blood. With the current policy in Malawi, the primary source of blood donations and collection is Malawi Blood Transfusion Service. However, during emergencies, relatives and friends may be requested to donate blood. Therefore, prior donor identification may be life saving in critical situations.

Overall, results show that knowledge of participants about key danger signs was very low, especially regarding danger or warning signs during antenatal, labour and delivery as compared to postnatal and the newborn. These results could be attributed to absence of relevant patient education to promote B/P and CR, and lack of information during ANC. Knowledge of the danger signs of obstetric complications is an essential step in recognition of complications and could enable women take appropriate action to access emergency care [11]. The results that some participants could identify at least one danger sign but very few identified three or more danger signs agree with those reported in India by Anya et al. [14]. Spontaneous knowledge of specific life-threatening complications was low in this study as also reported by other studies [14] although almost all women knew at least one and a significant minority knew up to three or more. Poor awareness of the obstetric complications of women may contribute to a delay in seeking and reaching care. Therefore mothers need to be conversant with all key danger signs because approximately 25% of maternal deaths occur during pregnancy [18]. Therefore there is a need to strengthen antenatal care education with more emphasis on danger signs of pregnancy during antenatal, labour and delivery, postnatal and newborn babies.

Result that mothers had a better knowledge of the key danger signs for the baby than for themselves during antenatal, labour and delivery and postnatal imply that mutigravid mothers may have accessed the information about children at the under-five clinic during the previous child. Results therefore show that at the under-five clinic, there was better coverage of danger signs of infants than at the ANC. Vaginal bleeding which is a serious danger sign during labour and delivery was not often known by the participants. This danger sign could have been emphasized to the women because haemorrhage is the leading cause of maternal mortality worldwide and responsible for 33% of all maternal deaths in Malawi [1,19]. In addition, the women could have been taught to identify danger signs which indicate severe pre-eclampsia and eclampsia such as severe headache, blurred vision, swelling of body, and fits. These signs could have been known to the women instead of mistaking them for normal signs of labour such as abdominal pains and backache. The results agree with those reported from Turkey [20] where women reported having received information about pregnancy and foetal development, but rarely about important danger signs during pregnancy (such as bleeding), preparation for the birth, and contraception. There is therefore a need to strengthen the ANC education so that women are knowledgeable about BP/CR.

Limitation of the Study

The study was confined to one health facility in Salima district hence the results may not be a true reflection of the whole district, therefore these results cannot be generalized country-wide although the trends similar national wide as reported by other studies [1] and other developing countries according to the available literature [5].

5. CONCLUSION

The participants in this study made a number of antenatal care visits and were therefore conversant with more routine antenatal care such as being physically examined, being given medication when necessary, the importance of good nutrition during pregnancy, and the importance of exercises and creation of ample time for rest during pregnancy. The postnatal mothers were conversant with the appropriate place for delivery, items to bring during labour and delivery, danger signs during postnatal period and for the infants. However, the mothers had limited knowledge about birth preparedness and complication readiness during pregnancy in general. Specifically, there was limited knowledge among the participants regarding prior arrangements for transport, having a blood donor, and danger signs during antenatal, labour and delivery. These are very important elements that must be emphasized during antenatal care education in order to reduce the high maternal and neonatal mortalities. Therefore, there is a need for midwives to ensure that all elements of BP/CR for women and their infants are well-known by all pregnant women during ANC.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The study was conducted as part of the senior author’s Master of Science degree in Midwifery at the University of Malawi, Kamuzu College of Nursing with a scholarship from UNFPA. The preparation of the manuscripts for publication was funded by the University of Tromso, Norway and the Agency for Norwegian Development Cooperation.

REFERENCES

- Geubbels, E. (2006) Epidemiology of maternal mortality in Malawi. Malawi Medical Journal, 18, 206-225.

- World Health Organization, UNFPA and The World Bank (2010) Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2008. Estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and the World Bank. World Health Organization Press, Geneva.

- National Statistical Office (NSO) and UNICEF (2011) Malawi demographic health survey 2010. Final Report, National Statistical Office and UNICEF, Lilongwe.

- Ministry of Health (2010) Emergence obstetric care services in Malawi. Report of the Nation Wide Assessment, E.Ces Print, Lilongwe.

- Agarwal, S., Sethi, V., Srivastava, K., Jha, P.K. and Baqui, A. (2010) Birth preparedness and complication readiness among slum women in Indore City, India. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 28, 383-391. doi:10.3329/jhpn.v28i4.6045

- Ministry of Health (2006) Malawi reproductive health standards. Ministry of Health, Lilongwe, E.Ces Print.

- Polit, D.F. and Beck, C.T. (2006) Essentials of nursing research: Principles and methods, 6th Edition, Wolters Kluwer, Lippincott and Willams and Wilkins, Philadelphia.

- Polit, D.F. and Beck, C.T. (2000) Essentials of nursing research: Appraising evidence for nursing practice. 7th Edition, Wolters Kluwer, Lippincott and Willams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, 192.

- Straubert, H.J. and Carpenter, D.R. (1995) Qualitative research in nursing: Advancing the humanistic imperative. Lippincott, Philadelphia, 326.

- World Health Organization (2002) Global action for skilled attendants for pregnant women. Family and community health. Department of Reproductive Health and Research, Geneva.

- Ministry of Health (2006) Malawi national reproductive health service guidelines. Malawi Ministry of Health and Population, Lilongwe, Malawi.

- Ministry of Health (2008) Focused antenatal care and prevention of malaria during pregnancy: Training manual for health care providers. Ministry of Health, Lilongwe, Malawi.

- Kamwendo, L.A. and Bullough, C. (2005) Insights on skilled attendance at birth in Malawi: The findings of a structured document and literature review. Malawi Medical Journal, 16, 40-42. doi:10.4314/mmj.v16i2.10858

- Anya, S., Hydara, A. and Jaiteh, E.S. (2008) Antenatal Care in the Gambia: Missed opportunity for information, education and communication. BMC Pregnancy and Child Birth, 8, 9. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-8-9

- Gabrysch, S. and Campbell, O.M.R. (2009) Still too far to walk: Literature review of the determination of delivery service use. MBC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 9, 1471- 2391.

- Hiluf, M. and Fantahun, M. (2007) Birth preparedness and complication readiness among women in Adigrat town, north Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal Health Development, 22, 14-20.

- Thaddeeus, S. and Maine, D. (1994) Too far to walk: Maternal mortality in context. Social Science Medicine, 38, 1091-1110. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(94)90226-7

- McCoy, D., Ashwwod-Smith, H., Ratsma, E., Kemp, J. and Rowson, M. (2004) Going from bad to worse: Malawi’s maternal mortality. Health Systems Trust and Global Equity Gauge Alliance, Durban.

- World Health Organization (2004) Beyond the numbers: Reviewing maternal deaths and complications to make pregnancy safer. WHO Report, Geneva.

- Turan, J.M., Bulut, A., Nalbant, H., Ortayli, N. and Akalin, A. (2002) The quality of hospital-based maternity care in Turkey: Findings regarding antenatal care.