Psychology

Vol.07 No.04(2016), Article ID:66009,7 pages

10.4236/psych.2016.74066

The Dialogue and the Relationship with Parents and Friends: A Research on Italian Adolescents’ Representations

Giulia Savarese

Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Salerno, Salerno, Italy

Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 11 March 2016; accepted 25 April 2016; published 28 April 2016

ABSTRACT

The goal was to understand what representations Italian adolescents have about the dialogue and the relationship with their parents and with the peer group, as well as to evaluate any differences. We interviewed 400 Italian adolescents, 200 males and 200 females, aged between 14 and 19 years. The instruments used were an ad hoc questionnaire and a free story. The results show significant differences in the communicative/relational support by parents and by the peer group, especially in relation to the confidences of their personal problems, the choice autonomy and the behaviors that encourage independence.

Keywords:

Adolescent, Communication, Family, Group of Peers

1. Introduction

In adolescence there are changes that affect body, behavior and mind ( Palmonari, 2001 ; Ellis, Del Giudice, Dishion, Figueredo, Gray, Griskevicius, & Wilson, 2012 ). They are often very strong and sudden for those who experience and observe them ( Cicognani & Zani, 2003 ; Triyanto, 2014 ). In fact, adolescence is considered as a preparation for adult life, a physical and sexual maturation, rebellion against parents, restructuring towards the past; furthermore, there is a restructuring of the personality and many significant pubertal changes are experienced, with the help of biological, psychological and even social factors ( Vianello, 1999 ; Sneed, Tan, & Meyer, 2015 ). The main task of adolescence development is the search for personal identity ( Erikson, 1968 ; Petter, 1999 ; Hudley, 2015 ), favored by the broadening of one’s cognitive horizon and the use of hypothetical-deductive thinking. Teenagers, in fact, perform a more and more in-depth reflection on themselves, on what they are, why they are what they are, and what could be if they were born and raised in a different context or historical moment ( Piaget, 1972 ; Paus, 2005 ).

Essential are the results of social relationships with parents and with the peer group. This research precisely analyses the characteristics of these reports and their relevant communication products.

Literature shows that, during adolescence, it is normal to experience temporary disruptions in relationships with parents. Communication is a key element within the family relationship, especially when the children are teenagers. When there is good communication within the family, it is more united and flexible ( Cicognani & Zani, 2003 ; Clark, 2015 ; Endang, 2015).

In adolescence there is less and less intimate closeness with parents. This detachment expresses the desire on behalf of adolescents, more privacy and less exchange of affection. What concerns parents, and mothers in particular, is being less informed and involved as to what happens to the child. In fact, while in childhood and early adolescence the people to confide in one’s feelings were the parents, with aging, confidants become friends, peers and intimate partners. Despite this, communication with the mother continues to be significant, as long as she is not too intrusive ( Cicognani & Zani, 2003 ; Clark, 2015 ).

Peers are to teenagers’ fundamental points of support for the realization of autonomy from parents. Adolescents with friends feel that they can obtain advice, ask them for help, and be willing to reciprocate; they can face with less anxiety and risk the new situations that come their way ( Petter, 1999 ). The comparison with peers allows the development and the satisfaction of personal needs. In social relations with others, the individuals learn to discuss, to consider different points of view, to mediate between distant positions from each other, etc. They find opportunities to build their own notions of social justice and opportunities to take on a role that rarely emerges in the relationship with adults, and that is to be the one who helps, supports and advises (younger people or at least those in need) ( Vianello, 1999 ; Heerde, Toumbourou, Hemphill, & Olsson, 2015 ). The greatest concern for the adolescent is to be accepted and confirmed in their choices, by the group of friends; later this affiliation need evolves into the need to belong and adolescents participate in those social situations which give support to their new self-image. Friendship can be categorized as an adolescent’s natural need ( Pietropolli Charmet, 1997 ; Hiatt, Laursen, Mooney, & Rubin, 2015 ). The youngster belonging to a group, considers the group itself as something of his/her own, a context in which they may have personal ties with others, where they can get something that would otherwise be unattainable and in which they feel to be important and independent. Within the group, adolescents compare themselves with others and verify their self-esteem through experiences both with successful outcomes and failure ( Thompson, 1992 ; Palmonari, 2001 ). In the relationship with the friend, in fact, you may even have misunderstandings and disappointments may occur; there can be tension, rivalry, jealousy and dislike, perhaps due to the fear of not being accepted by some more influential members. Experiencing these feelings, however, develops greater resilience and copes with stressful events ( Rapini, Farmer, Clark, Micka, & Barnett, 1990 ; Raffaelli, 1997 ).

The objective of the research is to understand which representations Italian adolescents have related to dialogue and relationship with parents and peer group, as well as to evaluate possible differences.

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

Research was carried out with two vocational high schools in Campania in Italy. Four hundred adolescents have participated, 200 males and 200 females, aged between 14 and 19 years.

2.2. Tools

a) A questionnaire (purposely designed, with two multiple answers) about the dialogue with parents and peer group:

1) What do you discuss with your parents/friends? (cross the answer)

-things you do with friends/parents

-your personal problems

-your problems at school or work

2) Assign a score 1 - 5 (1 = at all; 5 = very much) to the following statements:

My parents/friends support me in relation to:

-the changes in my physical aspect

-feeling in a bad mood

-my experiences with the other gender

-my school experience (performance, difficulties with teachers and classmates)

-my autonomy desires

-friendship reports

-things to believe in, those fundamental for life

-changes I experience within myself

b) A free story about:

-difficulties of adolescence age

-relationship and dialogue with parents and peer group: difficulties and resources

3. Results

3.1. Questionnaire Results

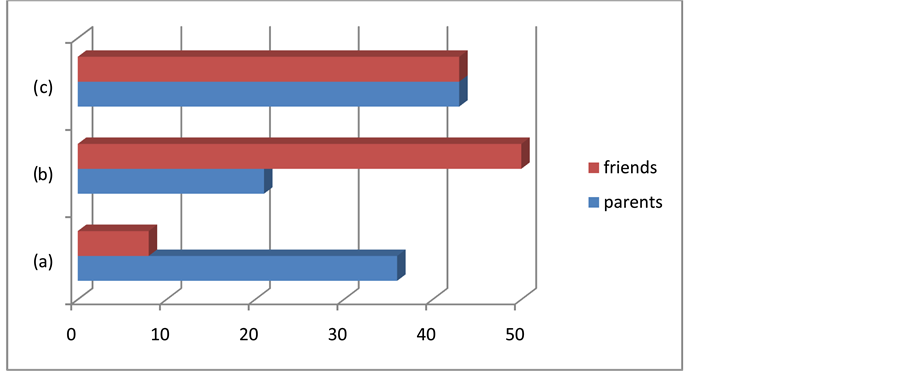

Figure 1 shows that 36% of the participants talk with parents about what they do with friends (answer “a”) while only 8% talk to friends about what they do in the family; the majority, 43%, claimed to speak, with an even proportion between family and friends, about work or school problems (answer “c”); finally, the second statement (“b” your personal problems) was chosen this way: if referred to the family by 21% of the sample, if referred to the peer group by 50%. The latter figure expresses the discomfort of children to communicate their personal problems with their parents and, on the contrary, the ease with which they feel more willing to talk about the same problems with peers.

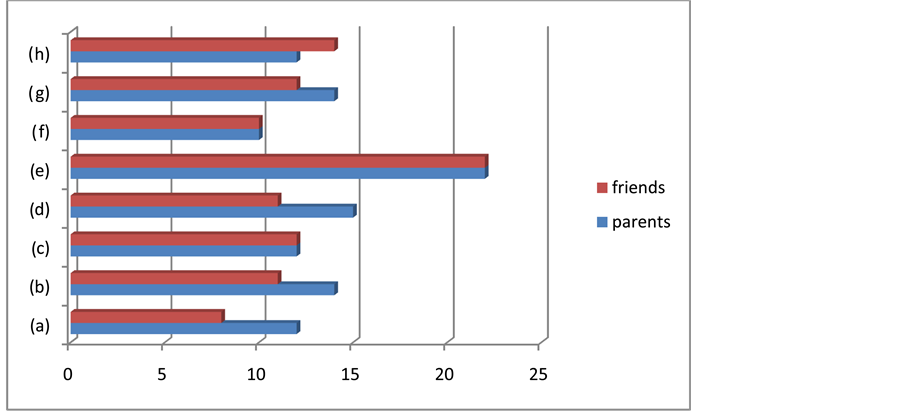

Figure 2 shows the data related to parental and friends’ support on the basis of proposed statements: 12% believe that parents are interested in their physical changes and accept them (answer “a”) (against 8% in relation to friends’ involvement); 14% feel parents close in bad days (answer “b”) (against 11% referred to friends’ closeness); 15% chose statement “d” referred to parents (against 11% referred to friends), and this highlights the fact that parents understand them enough when they struggle in school. Statement “g”, which corresponds to a percentage of 14% for parents (compared to 12% for friends), indicates that both parents and friends support, almost to the same extent, adolescents in the things they believe; 12% of participants who chose statement “h” referred to parents (against 14% to friends) makes us understand, because of the low percentage, that fathers and mothers are often not very close to the boy/girl in his/her inner transformation. Eleven percent chose, with regards to the family, answers “c” (against 12% of friends), “e” (against 22% of friends) and “f” (against 10% of friends). The latters show that parents have difficulty helping their child to approach the opposite sex, to support him/her in autonomous initiatives and also in friendships. This does not happen with friends, which mainly encourage the desires for the individual’s autonomy (statement “e”), as we understand from 22% which is exactly twice as much the one chosen by the family to the same statement.

Figure 1. What do you discuss with your parents/friends? (cross the answer) (chi square p > 0.01). (a) Things you do with friends/parents; (b) Your personal problems; (c) Your problems at school or work.

Figure 2. Assign a score 1 - 5 (1 = at all; 5 = very much) to the following statements: My parents/friends support me in relation to… (chi square p > 0.05). (a) The changes in my physical aspect; (b) Feeling in a bad mood; (c) My experiences with the other gender; (d) My school experience (performance, difficulties with teachers and classmates); (e) My autonomy desires; (f) Friendship reports; (g) Things to believe in, those fundamental for life; (h) Changes I experience within myself.

3.2. Free Story Results

We have analyzed the participants’ stories with the Content analysis through the “T-Lab 9.1” software and the Sequence analysis.

The two lemmas with most occurrences, meaning the most used by children, were “friendship” and “need”.

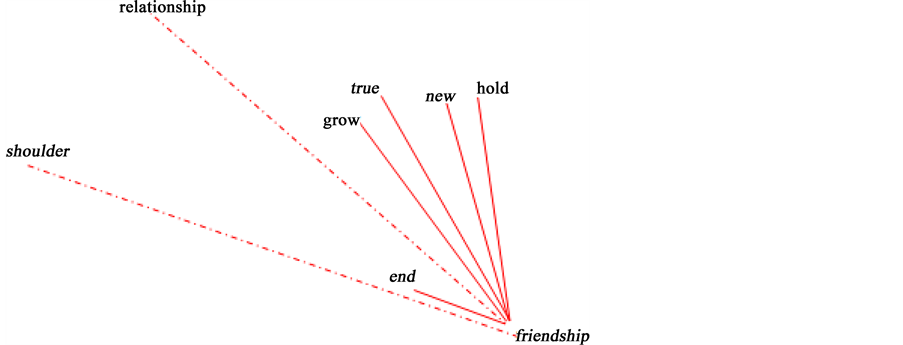

As you can see from Figure 3, “friendship “is seen as a time to grow, very supportive, because friends provide a shoulder for support. Teenagers who need to keep relations, hope that they are true and can never end.

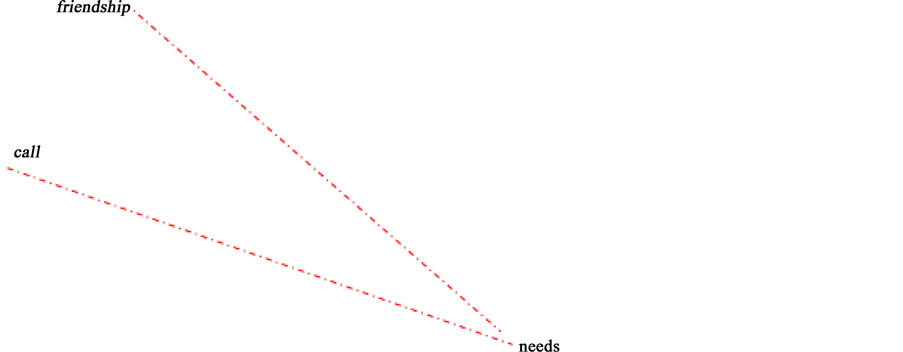

In Figure 4 the lemma “needs” is associated to the sequence with the terms friendship and call. It seems that having friends is the greatest need of the adolescents interviewed.

From the analysis of the free narrative, differences by age have emerged between the responses of early adolescence (14 - 16 years) and late adolescence children (17 - 19 years), and by gender, among boys’ and girls’ responses (all with chi square p > 0.05).

3.3. Differences by Age

Early adolescence, in general, is characterized by an increase of conflict with parents. In fact, the children interviewed between 14 and 16 years, compared to the older ones, claimed they would like to be more respected for their opinions both by parents and friends. The discrepancy in responses between the two age groups considered could be explained because, in late adolescence, children have passed certain conflicts and are already mature enough to understand that not everyone can share the same ideas and impressions.

With regard to autonomy, older kids have expressed a greater desire for autonomy, than the younger ones. Becoming independent is one of the steps of adolescent development, a prerequisite for becoming adults, competent and responsible. Autonomy has a primary importance, because of the many and profound changes that assail children at different levels: physical, sexual, for the formation of emotional and extra-familial relationships, but also for the social expectations regarding the appropriate attitudes held by adults.

3.4. Differences by Gender

Both with their mothers and girlfriends, girls are more likely to talk about everything related to personal issues and their intimacy; however males have more difficulty to open up and show their weaknesses on the most intimate aspects of life with both parents and friends, preferring to discuss more futile things or maybe school issues.

Figure 3. Sequence analysis of the word “friendship”.

Figure 4. Sequence analysis of the word “needs”.

In terms of “desire for autonomy”, the older girls, having received a generally more restrictive and controlled education than males, ask their parents for more freedom with regard to nights out, curfew hours, attending certain places. Younger adolescents are in a period characterized by the process of “separation-individuation” in the sense that they feel the need to separate physically and psychologically from their parents, but, in reality, are not yet ready to do so, totally without their guide and their support.

4. Discussion

The dialogue is essential for a good relationship between parents and teenagers, although we can often observe a “physiological” less closeness, intimacy and dialogue of adolescents with their parents. The confidantes become friends, classmates and intimate partners ( Cicognani & Zani, 2003 ).

A study suggests that good family communication is associated with lack of disagreement between adolescents and parents. They also indicate a positive association between family communication and adolescent self- esteem, certain aspects of adolescent well-being and type of coping strategy employed ( Jackson, Bijstra, Oostra, & Bosma, 1998 ). In another study, that have compared interpersonal relationships of adolescents from Canada, Belgium, and Italy, the family was found to occupy a more central role in the relational world of Italian adolescents, whereas friends were found to occupy a more important place for Canadian youth, but for three countries there are the importance of friends in the relational life of adolescents, the privileged position of the mother in the family, and the distant position of the father ( Claes, 1998 ). Negative interactions with mothers were significantly related to adolescents’ greater conflict with friends, poorer focus on tasks, and poorer communication skills ( Shomaker & Furman, 2009 ). However, adolescents’ attributions for their communication problems significantly predicted their satisfaction with parents than the ways they interpret the problems ( Vangelisti, 1992 ). A support in relationships with parents tended to be related to support in romantic relationships and friendships ( Furman, Simon, Shaffer, & Bouchey, 2002 ).

Finally, communication patterns based on mutual respect and equality help with parents and friends is important to prevent adolescent risks onset ( Otten, Harakeh, Vermulst, Van den Eijnden, & Engels, 2007 ). Italian teenagers surveyed have confirmed what literature tells us about the dialogue and the relationship between parent-adolescent and among the peer group-teenager, although we have not identified a specific study on representations adolescents. Our study has identified significant differences in the communicative/relational support by parents and by the peer group.

5. Conclusion

Teenagers need friends and confide in them much more than they do with their parents, especially with respect to personal problems.

In their family, adolescents often feel unsupported in their ability to make autonomous choices, and they are usually unable to make their own experience. The peer group, however, consistently stimulates the adolescent’s desire to become autonomous and to be independent from the physical, emotional, social and psychological point of view.

Acknowledgements

The source of funding for all authors is “Legge 5/2007, Savarese, Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Salerno”.

Cite this paper

Giulia Savarese, (2016) The Dialogue and the Relationship with Parents and Friends: A Research on Italian Adolescents’ Representations. Psychology,07,648-654. doi: 10.4236/psych.2016.74066

References

- 1. Cicognani, E., & Zani, B. (2003). Parents and Adolescents. Roma: Carocci.

- 2. Claes, M. (1998). Adolescents’ Closeness with Parents, Siblings, and Friends in Three Countries: Canada, Belgium, and Italy. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 27, 165-184. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1021611728880

- 3. Clark, A. M. (2015). Family Communication Patterns and Adolescent Emotional Well-Being: Cross Classification of Mother-Child and Father-Child Interactions. http://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/xmlui/handle/1957/56498

- 4. Ellis, B. J., Del Giudice, M., Dishion, T. J., Figueredo, A. J., Gray, P., Griskevicius, V., & Wilson, D. S. (2012). The Evolutionary Basis of Risky Adolescent Behavior: Implications for Science, Policy, and Practice. Developmental Psychology, 48, 598. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0026220

- 5. Erikson, E. H. (1968). Youth and Crisis. Norton & Company, New York-London, 17.

- 6. Furman, W., Simon, V. A., Shaffer, L., & Bouchey, H. A. (2002). Adolescents’ Working Models and Styles for Relationships with Parents, Friends, and Romantic Partners. Child Development, 73, 241-255. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00403

- 7. Heerde, J. A., Toumbourou, J. W., Hemphill, S. A., & Olsson, C. A. (2015). Longitudinal Prediction of Mid-Adolescent Psychosocial Outcomes from Early Adolescent Family Help Seeking and Family Support. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 25, 310-327. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jora.12113

- 8. Hiatt, C., Laursen, B., Mooney, K. S., & Rubin, K. H. (2015). Forms of Friendship: A Person-Centered Assessment of the Quality, Stability, and Outcomes of Different Types of Adolescent Friends. Personality and Individual Differences, 77, 149-155. http://tlab.it/en/plus2015.php http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.12.051

- 9. Hudley, C. (2015). Adolescent, Identity and Schooling: Diverse Perspectives. NY: Routledge.

- 10. Jackson, S., Bijstra, J., Oostra, L., & Bosma, H. (1998). Adolescents’ Perceptions of Communication with Parents Relative to Specific Aspects of Relationships with Parents and Personal Development. Journal of Adolescence, 21, 305-322.http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jado.1998.0155

- 11. Otten, R., Harakeh, Z., Vermulst, A. A., Van den Eijnden, R. J., & Engels, R. C. (2007). Frequency and Quality of Parental Communication as Antecedents of Adolescent Smoking Cognitions and Smoking Onset. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 21, 1-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0893-164x.21.1.1

- 12. Palmonari, A. (2001). Adolescents. Bologna: Il Mulino.

- 13. Paus, T. (2005). Mapping Brain Maturation and Cognitive Development during Adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9, 60-68. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.008

- 14. Petter, G. (1999). Psychology and the Adolescent in the Secondary School. Firenze: Giunti.

- 15. Piaget, J. (1972). Intellectual Evolution from Adolescence to Adulthood. Human Development, 15, 1-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000271225

- 16. Pietropolli Charmet, G. (1997). Friends, Schoolmates, Accomplices. Milano: Franco Angeli.

- 17. Raffaelli, M. (1997). Young Adolescents’ Conflicts with Siblings and Friends. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 26, 539- 558. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1024529921987

- 18. Rapini, D. R., Farmer, F. F., Clark, S. M., Micka, J. C., & Barnett, J. K. (1990). Early Adolescent Age and Gender Differences in Patterns of Emotional Self-Disclosure to Parents and Friends. Adolescence, 25, 959-976.

- 19. Shomaker, L. B., & Furman, W. (2009). Parent—Adolescent Relationship Qualities, Internal Working Models, and Attachment Styles as Predictors of Adolescents’ Interactions with Friends. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 26, 579-603. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0265407509354441

- 20. Sneed, C. D., Tan, H. P., & Meyer, J. C. (2015). The Influence of Parental Communication and Perception of Peers on Adolescent Sexual Behavior. Journal of Health Communication, 20, 888-892. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2015.1018584

- 21. Thompson, M. S. (1992). The Impact of Formal, Informal, and Societal Support Networks on the Psychological Well-Being of Black Adolescent Mothers. Social Work, 37, 322-328.

- 22. Triyanto, E. (2014). Family Support Needed for Adolescent When Puberty Period. International Journal of Nursing, 3, 51-57.

- 23. Vangelisti, A. L. (1992). Older Adolescents’ Perceptions of Communication Problems with Their Parents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 7, 382-402. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/074355489273007

- 24. Vianello, R. (1999). Developmental Psychology: Adolescence, Adulthood, Old Age. Bergamo: Edizioni Junior.