Journal of Cancer Therapy

Vol.06 No.04(2015), Article ID:55425,15 pages

10.4236/jct.2015.64033

Pediatric Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Retrospective 7-Year Experience in Children & Adolescents with Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Treated in King Fahad Medical City (KFMC)

Nahla Ali Mobark1*, Suha A. Tashkandi2, Wafa Al Shakweer3, Khalid Al Saidi2, Suha Fataftah2, Mohammed M. Al Nemer1, Awatif Alanazi1, Mohammed Rayis1, Walid Ballourah1, Othman Mosleh1, Zaheer Ullah1, Fahad El Manjomi1, Musa Al Harbi1

1Department of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, Comprehensive Cancer Centre, KFMC, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

2Department of Cytogenetic and Molecular Cytogenetic Laboratory, KFMC, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

3Department of Anatomical Pathology, KFMC, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Email: *nmobark@kfmc.med.sa

Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 10 March 2015; accepted 7 April 2015; published 8 April 2015

ABSTRACT

Background: Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is an aggressive malignant disease in children and adolescents. Although it is the fourth most common malignancy in Saudi children as reported in Saudi cancer registry, less information is available about pediatric Non-Hodgkin lymphoma and its outcome in Saudi Arabia. Study Objectives: To provide demographic data, disease characteristics, treatment protocol, toxicity and outcome of treatment in children & adolescents with Non-Hodg- kin’s lymphoma treated at KFMC. This study will form base line for future studies about pediatric Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in KFMC, which may help to improve outcome for children with cancer in Saudi Arabia. Study Patients and Method: We retrospectively analyzed 28 children and adolescents diagnosed to have Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma at KFMC between December 2006 and December 2013, followed-up through June 2014. Results: Of the 28 patients, 10 (35.7%) girls and 18 (64.3%) boys, the male-to-female ratio was 1.8; 1. The median age at time of diagnosis was 6.4 years old (range 2.0 to 13.0 years old). The majority of patients (64.3%) were aged between 5 and 12 years old. Burkitt’s lymphoma BL/BLL was the most common pathological subtype (60.7%), and DLBCL was the second most common subtype (21.4%). Abdominal and Retroperitoneal involvement was the most common primary site (78.6%) including the ileocaecal region. Most of the children presented with advanced Stage III and IV (75%), Cytogenetic study which screens specifically for the t (8; 14) (q24; q32) a characteristic genetic feature of Burkitt’s Lymphoma was obtained from 21 patients, variant rearrangement was observed in 3/21 samples and complex chromosomes karyotype in addition to IGH/MYC rearrangement was observed in 2/21 samples. Those patients presented with very aggressive lymphoma and combined BM and CNS involvement. We use the French-American-British Mature B-Cell Lymphoma 96 Protocol (FAB LMB 96) for treat- ment fornewly diagnosed Mature B-Cell type NHL and high risk ALL CCG 1961 Protocol for lymphoblastic lymphoma and international Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma 99 Study Protocol for ALCL. The median follow-up in patients not experiencing an adverse event was 53.1 months. The estimated 3-year EFE and OS rates in the entire cohort of patients with newly diagnosed NHL treated in the KFMC were 85.2% and 89.2% respectively; Overall survival (OS) rate of patients with mature B-cell-NHL was 88.9%. Conclusion: The outcomes and survival in our small series appeared to be excellent compared with those reported in other international trials even though most of our patients presented in advanced stage of the disease. We feel that the importance of the current study is to document the relative distribution of various types of pediatric non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas and age-specific distribution in different Histological subtypes.

Keywords:

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, Disease, Patients, Children and Adolescents

1. Background

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is an aggressive malignant disease in children and adolescents; it has been reported to be the fourth most common malignancy amongst Saudi children [1] .

This study highlights the clinical features and outcomes of pediatric lymphoma in a quaternary care center in Saudi Arabia. King Fahad Medical City KFMC is a primary referral center for the Ministry of Health in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia for pediatric neoplasms and possibly reflects the distribution of subtypes of pediatric lymphomas within the kingdom. Pediatric Oncology Department is one of the major sections of comprehensive Cancer Centre in KFMC which starts accepting new cases of pediatric neoplasm including non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 2006 and now it is considered as the second center in Saudi Arabia which provides comprehensive care for children with cancer. This study intends to prove the efficacy of our treatment strategy for children with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) treated in our center.

The most common NHL type in children are lymphoblastic lymphoma (LBL) [precursor-B-cell or T-cell], patients with mature B-cell-NHL (B-NHL), Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL), Burkitt’s leukemia, diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBL), and anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL), each of which has a different treatment strategy [2] .

Multidisciplinary pediatric cooperative group collaborations over the past 25 years in children and adolescents with mature B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma have reported a 99% survival rate in limited-risk patients and 90% survival rate in intermediate-risk patients and approximately 70% survival rate of children with high risk NHL treated by intensive risk-adapted chemotherapy [3] - [5] .

Mature B-cell NHL with CNS involvement has been associated with significantly inferior EFS, especially in patients with intermediate and advanced risk [6] .

Cytogenetic analysis plays a cruicial role in the diagnosis of lymphoid malignancies. The gold standard analysis is done by conventional karyotype analysis and Fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH), which give identification for the major abnormalities involved in lymphomas [7] [8] .

2. Patients and Methods

Twenty-eight patients < 16 year old diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, BL or BLL, DLBCL; T cell LL and ALCL according to the Revised European-American Lymphoma (REAL) classification [9] . Patients with relapsed non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma or those above 16 year old were excluded from study.

2.1. Data Collection and Analysis Procedure

We reviewed patients’ medical records, radiology images & stored pathology specimen. Information collected included: age at diagnosis, gender, clinical presentation, tumor location, disease characteristics that included pathological subtypes, cytogenetic profile and prognostic factors. Treatment plan, treatment toxicity and outcome of treatment including relapse, death from all causes and occurrence of second malignancies were also recorded.

Pearson’s chi-square test was used to determine the significant association among overall survival and clinical stage, node, BM, CNS, etc.

The primary outcome measure of the study was event free survival (EFS) & overall survival (OS). EFS was defined as minimum time to relapse, progressive disease, second malignancy, or death from any cause; OS was measured from the date of diagnosis until the date of death from any cause or date of last contact. EFS & OS was estimated with Kaplan-Meier method. P-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All data was entered and analyzed through statistical package SPSS version 20.

This study was conducted in compliance with the Helsinki accords and was granted an approved IRB from the Ethics Board of King Fahad Medical City, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

IRB Registration Number with KACST, KSA: H-01-R-012;

IRB Registration Number with OHRP/NIH, USA; IRB00008644;

Approval Number Federal Wide Assurance NIH, USA; FWA00018774.

2.2. Staging, Risk Group & Treatment Protocol

The French-American-British Mature B-Cell Lymphoma 96 Protocol (FAB LMB 96) was used for treatment for newly diagnosed pediatric Mature B-Cell type and NHL, the high risk ALL CCG1961 Protocol was used for lymphoblastic lymphoma and the international Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma 99 Study Protocol for ALCL.

Initial evaluation included history, physical examination, complete blood count, peripheral blood smears, renal and hepatic function tests; bone marrow biopsy, cerebrospinal fluid examination at the time of the first intrathecal therapy. Pre-treatment imaging studies included chest X-rays, ultrasonography, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and functional imaging (gallium scan and fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography [PET]).

Patients were staged according to Modified Murphy Staging, Seminars in Oncology 1980 [10] , and according to (FAB LMB 96) Protocol Mature B-non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, patients will be divided into 3 tratment group.

Group A. Completely resected stage I or completely resected abdominal stage II lesions. These patients received two courses of cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, and doxorubicin (COPAD) without intrathecal (IT) chemotherapy.

Group B. include any cases not eligible for Group A or Group C. These patients received 7-day, low-dose, reduction phase cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (COP) therapy with intrathecal (IT) chemotherapy. Then induction therapy consisted of two cycles of fractionated COPAD and high-dose methotrexate HD-MTX 3 g/m2 (COPADM). Patients then received two consolidation cycles of cytarabine and HD-MTX (CYM). Patients received IT chemotherapy prophylaxis during all phases of the therapy. Patients with less than 20% response on day 7 of COP and patients with residual disease after CYM-1 (that is, the first cycle of CYM) were transferred to rescue group C therapy as outlined.

Group C. Any CNS involvement and /or bone marrow involvement with greater than 25% blast cells. These patients received prophase COP. Induction therapy consisted of two cycles of COPADM (with HD-MTX 8 g/m2). Consolidation consisted of 2 identical courses of high-dose cytarabine with Etoposide (CYVE). Patients with CNS disease did not receive cranial radiation but received additional IT therapy as well as an additional HD- MTX course between consolidation courses, followed by 4 maintainence courses of chemotherapy.

2.3. Early Response Evaluation and Follow-up

Physical examination of all clinically documented sites of disease was performed prior to the initiation of each cycle, ultrasound examination of the abdomen and pelvis and chest X-rays (if abnormal at presentation) were performed after first cycle of chemotherapy. The patient was labeled as “early responding” if tumor response above 20% reduction at day 7. All patients with mature B-cell, non-Hodgkin lymphoma underwent response evaluation by CT scan and functional imaging after CYM-1.

Relapses were confirmed by biopsy. Retrieval therapy (cytoreductive chemotherapy, with or without consolidative autologous stem cell transplant ABMT) was not specified and was administered according to primary physician’s preference.

Follow-up evaluations included history, physical examination, and laboratory examinations every three months during the first year, every four months during the second and third year and every six months up to five years off therapy and yearly thereafter. PET and CT scans were performed at the first and second year off-the- rapy and/or as clinically indicated. Long term follow up clinic visit five years off-therapy including ongoing assessments for late treatment complications included annual evaluations of growth and pubertal development. Thyroid, pulmonary, and cardiac functions were done annually during long term follow up clinic visit.

2.4. Cytogenetic Study

Cytogenetic evaluation for Paraffin Embedded Tissue (PET) sample is done by FISH analysis, both results for the LSI MYCC (Abbott, USA) and LSI IGH/MYCC CEP 8 (Abbott, USA) DNA probes were included unstained PET sections with a thickness between 2 -4 μm are prepared according to the KMFC Histopathology lab routine methods. Cytogenetic evaluation for Bone Marrow (BM)/Leukaemic Blood BM/LB is done by GTG karyotype analysis and FISH at diagnosis. The samples non-stimulated cultures in RPMI 1640 X1 are harvested following the routine cytogenetics methods, all culture additives are from Gibco Life Technologies, UK except the FBS (PAA, Austria). Microscopic analysis for both karyotype analysis and FISH analysis was done using the Nikon 90i microscope (Nikon, Japan) and the Cytovision image analysis system (Applied imaging, USA). For karytope analysis, slides were examined under a bright field, where a total of 20 metaphases were analyzed for each sample. For FISH analysis, slides were examined under epifluorescence using the appropriate filter set-up as images were acquired by a Photometric cooled CCD Camera (Leica, Germany). All scoring decisions were made by both direct and image analysis, and results were verified by two independent observers.

3. Results

The male-to-female ratio was 1.8:1; i.e. 18/28 males and 10/28 females. The median age at time of diagnosis was 6.4 years old (range 2.0 to 13.0 years old; mean 6 years old). With 64.3% of the patients aged between 5 - 12 years old.

3.1. Histopathology Distribution

Burkitt’s lymphoma BL/BLL was the most common pathological subtype (n = 17, 60.7%)

Summary of histopathology diagnosis and gender distribution of the cases is in Table 1.

Most of the children presented with Stage III and IV (n = 21; 75%). The staging of the disease and histological subtypes are summarized in Table 2.

3.2. Cytogenetic Profiling

Cytogenetic analysis for translocation involving the MYCC oncogene was done on 21 patients with Mature B- Lymphoma; PET/FISH was carried out on 15 samples and for the remaining 5 FISH was carried out on BM samples [4] , peripheral blood smears LB [1] .

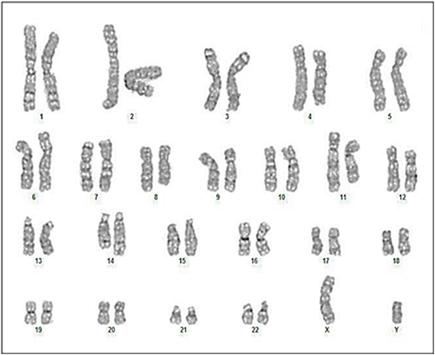

Case 3 and case 15 of the GTG karyotype cases showed complex rearrangements in addition to the IGH/ MYCC rearrangement, the two patients presented with very aggressive lymphoma and combined bone marrow and CNS involvement.

Case 3 was a six-year-old child with Burkitt’s lymphoma stage IV, positive MYCC oncogene with complex rearrangements in addition to the IGH/MYCC rearrangement, with combined CNS and bone marrow involvement and he was slow responder and died due to progression of disease post consolidation phase (Figure 1).

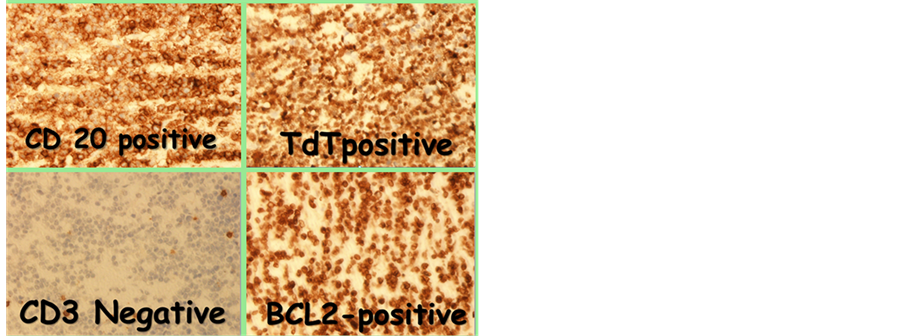

Case 15 was 5 years old stage IV Burkitt’s lymphoma with complex karyotyping rearrangements and structural abnormalities in addition to the variants of IGH/MYCC rearrangement presented with cranial nerve palsy, combined bone marrow and CNS involvement, MRI brain showed diffuse infiltrative changes involving the caldarium and the pachymeninges and the skull base, CSF analysis was full of blasts. He responded very well to chemotherapy (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Other variant results for the FISH signal are shown in Figure 4.

Cytogenetic results of Mature B-NHL cases are shown in Table 3.

Table 1. Summary of histopathology diagnosis and gender distribution of the cases.

Table 2. Clinical staging according to the Modified Murphy Staging and histopathology subtypes according to the WHO criteria.

Figure 1. (Case 3) 6-year-old child with Burkitt’s lymphoma stage IV, presented with very aggressive lymphoma with combined CNS and bone marrow involvement complex karyotyping rearrangements in addition to the IGH/MYCC rearrangement 47, XY, +1, der t(1; 15) (q10; q10), t(8; 14) (q24; q32), der(9) (q22), −13, −15, +2 mar [12] /46, XY [8] .

Figure 2. (Case 15) 5-year-old boy stage IV Burkitt’s lymphoma with complex karyotyping rearrangements and structural abnormalities in addition to the IGH/MYCC rearrangement. (a) (Case 15 major clone) 46, XY, t(8; 14) (q24.1; q32) dup (11) (q13q23) [17] /84, XXYY, −3 −3, dup (3) (q13q23), −4, −6, −8, t(8; 14) (q24.1; q32), t(8; 14) (q24.1; q32), −10, dup (11) (q13q23), −17, −22 [3] ; (b) (Case 15 minor clone) 46, XY, t(8; 14) (q24.1; q32) dup (11) (q13q23) [17] /84, XXYY, −3 −3, dup (3) (q13q23), −4, −6, −8, t(8; 14) (q24.1; q32), t(8; 14) (q24.1; q32), −10, dup (11) (q13q23), −17, −22 [3] .

Figure 3. (Case 15) FISH of the LSI IGH/MYCC/CEP 8 tri-color dual fusion DNA Probe. (a) shows the classical IGH/MYCC rearrangement; (b) shows the Variant (Atypical) FISH rearrangement with an additional chromosome 8 and additional fusion, also note the size of the metaphase (high chromosomes number).

3.3. Clinical Presentation

Abdominal and retroperitoneal involvement was the most common primary site (n = 22, 78.6%). The head and neck region was the second most common site of disease involvement (n = 8, 28.6%), followed by mediastinal (n = 6, 21.4%), splenomegaly was presented in (n = 5, 17.9%) and hepatomegaly in (n = 8, 28.6%).

(n = 5, 17.9%) of patients presented with a right lower quadrant abdominal mass or acute abdominal pain caused by an ileocecal intussusceptions. An exploratory laparotomy was indicated for diagnostic purposes and in some patients, led to complete resection of the tumor with the involved segment of gut and its associated mesentery, followed by an end-to-end anastomosis. Most of the T-lymphoblastic lymphomas showed mediastinal or pleural involvement, other unusual sites of disease include parotid, ovaries, uterus, breasts, epidural space, and bone.

Figure 4. (Case 16) FISH result of the variant IGH/MYCC rearrangement from the PET sample of this patient. Figure 4(a) is the FISH result for the LSI MYCC Break part DNA probe showing rearrangement involving the MYCC Gene region. Figure 4(b) is the LSIIGH/MYCC/ CEP8 tricolor dual fusion BNA probe showing a single fusion only, this result is positive of the IGH/MYCC rearrangement but with a possible deletion at one of the derivative chromosomes.

Bulky disease as defined by mass or node/aggregate > 6 cm was present in (n = 12, 42.9%).

In patients with stage IV disease, bone marrow involvement occurred in (n = 7, 25.0%) of cases and CNS involvement occurred in (n = 6, 21.4%).

(n = 8, 28.5%) of patients presented with high uric acid at presentation but only (n = 3, 10.7%) had impaired renal function due to kidney infiltration or/and acute tumor lysis syndrome requiring Hemodialysis at the time of diagnosis.

Only (n = 6, 21.4%) had some degree of liver impairment due to lymphoma involvement at diagnosis.

Anemia defined by decrease hemoglobin of two standard deviations below normal was the most common hematologic finding at diagnosis (n = 20, 71.4%), mostly microcytic anemia (n = 17, 60.7%) with reduced iron stores as documented by reduced iron staining in bone marrow biopsy, only (n = 7, 25%) patients had anemia due to bone marrow involvement. Anemia was also commonly was associated with stage III and IV, bulky tumor, elevated LDH, and low serum albumin.

Further, two adolescent girls (7.2%) had ovarian infiltration at presentation. The first case was a 12-year-old girl with stage III precursor B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma, presented with huge LT pelvic and abdominal mass 21.5 × 20.0 × 18.5 cm in maximum dimension on CT and started on high risk ALL CCG 1961 chemotherapy protocol, radiological evaluation post delayed intensification II phase of chemotherapy showed LT pelvic residual mass with low level of FDG uptake on PET scan. She had complete surgical excision of residual mass and the attached LT ovary with LT oophorectomy with excellent recovery (Figure 5).

The second case is a 13year-old female with aggressive type of Burkitt’s lymphoma combined bone marrow and CNS involvement positive c-myc t(8q14), positive CD20, CD10, Bcl6, negative TdT, strongly positive Ki67 presented with diffuse breast mass, hepatic impairment CT sowed multiple hepatic lesion, extensive mesenteric lymphadenopathy with large uterine mass and bilateral ovarian infiltration. There was left para-spinal mass at the level of L3 and L4 with intra-spinal extension, started on Group C CNS positive FABLMB 96 protocol due

Table 3. Summary of the Cytogenetic analysis result. TC-Tissue Culture, BM-Bone Marrow, LB-Leukemic peripheral blood, BL-Burkitt’s Lymphoma, BLL-Burktt’s Like Lymphoma, DLBCL-Diffused Large B Cell Lymphoma, V-Variant (Atypical) FISH signal pattern, V/C-Variant and Complex rearrangement by FISH.

to the associated hepatic impairment at diagnosis. She received 50% reduction of initial chemotherapy post consolidation evaluation and she was in complete metabolic remission on PET scan.

3.4. Treatment Response for Mature B NHL

Of the 23 patients diagnosed with mature B NHL; 22 were evaluated post reduction phase of chemotherapy, one patient was not evaluated post reduction phase of chemotherapy due to the transfer to another hospital. 10 (45.5%) were early responder after reduction phase of chemotherapy, while 12 (54.5%) patients were not early responder (Table 4).

Post consolidation evaluation majority of patients (n = 17, 77.3%) were in complete remission (CR), (n = 5, 22.7%) of group B patients were not in complete remission (CR) after CYM-1 consolidation phase of chemotherapy and upgraded to group C protocol (Table 5).

Figure 5. Unusual presentation of ovarian non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma 12 years old girl with precursor B Lymphoblastic Lymphoma.

Table 4. Response following reduction phase COP* FABLMB 96 prognostic group.

3.5. Adverse Events

All of the patients were admitted to the hospital for diagnostic work-up and administration of chemotherapy later hospital admission was required to treat intensive therapy-related complications which were commonly associated with stage III and IV. Treatment related toxicity, the use of total parental nutrition, parental opioid use to control pain, any modification of chemotherapy to avoid further toxicity in next cycles is summarized in Table 6.

One case of septic death more than 6 months post end of therapy happened was reported in a 12-year-old ado- lescent girl abdominal DLBCL stage III with ataxia telangiectasia, cerebellar atrophy, immunodeficiency, started on group B FAB LMB 96. She developed sever toxicity following COPADM cycles in the form of HSV positive mucositis, typhlytis, gastro intestinal bleeding, culture negative septic shock that needed recurrent PICU admission This extreme toxicity was managed by 50% reduction of subsequent chemotherapy cycles (doxorubicin, Methotrexate, cyclophosphamide) and monthly infusions of IV immunoglobulin to optimize her immune status. Post consolidation evaluation showed above 80% reduction of tumor size, but still unresectable intra-abdominal

Table 5. Response after consolidation FABLMB 96 prognostic group.

Table 6. Treatment toxicity.

residual mass, as such, she was upgraded to group C and was in complete remission at end of therapy. However, more than 6 months post end of therapy her family stopped clinic follow up and as such, the patient was not seen for long time, until she presented with severe RSV pneumonia, complicated by respiratory failure and septic shock and thus died while she was in remission.

In this study, we reported one case of secondary malignancy, 3-year-old girl with stage III abdominal Burkitt’s lymphoma started group B FAB LMB 96 protocol, post CYM1 consolidation evaluation showed residual tumor around internal iliac vessels bilaterally, radiologically active lymph nodes upgraded to Group C chemotherapy which resulted in complete resolution of the residual mass at the end of therapy. During follow up 2 years post therapy, she presented with pancytopenia without palpable adenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. Bone marrow aspiration showed acute myelomonocytic leukemia AMLM4 with abnormal MLL rearrangement at chromosome 11q23 which was consistent with therapy related leukemia. She was referred for bone marrow transplant, no matched sibling donor was available and she died 6 months post cord blood transplant.

3.6. EFS and OS

The median follow-up in patients not experiencing an adverse event was 53.1 months (range: 16 - 89).

The estimated 3-year EFS and OS in the entire cohort of patients with newly diagnosed NHL treated in KFMC were 85.2% and 89.2% respectively (Figure 6 and Figure 7). Overall survival (OS) rate of patients with mature B-cell-NHL was 88.9% (Figure 8).

Figure 6. Event free survival for all NHL patients treated in KFMC.

Figure 7. Overall survival for patients with NHL treated in KFMC.

Figure 8. Overall survival of patients with mature B-Non Hodgkin Lymphoma.

4. Discussion

Our study group demonstrated a marked male predominance especially in children above five years old and those younger than 12 years old which was similar to international reports [11] .

Furthermore, histological subtypes of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma appeared to be age related. For example, Burkitt’s lymphoma appeared to be higher in children between the ages of 5 and 12 years old followed by diffuse large B cell lymphoma (Table 7), whereas lymphoblastic lymphomas were spread across all age groups. A similar distribution was previously reported in the United States [12] and in other studies from the Middle East and gulf area [13] . Anaplastic lymphomas have typically been reported in older children and adolescents [14] . However, in our series a single case of anaplastic lymphoma was treated in a child that was six years old.

The most common site of disease in our patients with mature B Lymphoma was the abdomen followed by head and neck. In contrast to reports on endemic Burkitt’s lymphoma in the literature, jaw involvement was not seen in our patients with Burkitt’s lymphoma [15] .

We also noted 2 cases of unusual presentation of ovarian non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in our series. Ovarian infiltration in pediatric non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) at presentation is very rare and information on its outcome is scarce and mainly based on case reports and small series [16] [17] . The outcome in both cases was excellent following aggressive treatment.

Majority of patients presented with anemia (71.4%) which is a well-known poor prognostic factor in Malignant lymphomas. However, in our patients the presence of anemia at diagnosis did not appear to correlate with survival. The pathogenesis of anemia in lymphoma is unclear. Most of our patients presented with microcytic Anemia (60.7%) with reduced iron stores which might reflect the high incidence of iron deficiency anemia in Saudi children [18] or may reflect the stress of malignancy and associated intestinal lymphoma mal absorption. A recent study suggested the role of hepcidin, an iron-regulated acute-phase protein in malignancy associated Anemia [19] , as such, further studies are required to determine whether this factor plays a role in the prevalence of anemia in Saudi children with cancer.

A large percentage of our patients (75%) presented with fairly advanced stage III/IV diseases, multiple reasons may be responsible for this delay in cancer diagnosis despite the wide availability of health care facilities

Table 7. Demographic characteristics and risk factors in relation to age.

all over the Saudi Kingdom, and these include first: lack of rapid efficient referral system of sick children with cancer from the periphery hospitals especially in the remote areas in Saudi kingdom to pediatric Oncology Centers and the limited bed capacity of those centers that limiting the acceptance of new patients; second: inadequate familiarity of the primary care physician and general pediatricians with the early warning signs and symptoms of pediatric cancer, third: the widely used Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) as well as traditional dietary habits in the community like honey and black seed which may delay seeking proper medical advice [20] .

Fundamentally, In our experience with FAB LMB 96 Protocol for mature B lymphoma patients, the excellent supportive care that we provide in our center and prompt management of infections and metabolic complications reduce markedly the mortality and morbidity of this intensive chemotherapy protocol [21] , the incidence of Mucositis grade III/IV post HDMTX was (50.0%), but coincidental herpes simplex virus HSV infection in some Patients (21.4%) increase severity of mucositis, but it was found that prophylactic use of acyclovir for patients with positive HSV infection minimized the severity of Mucositis in next cycle.

Use of recombinant urate oxidase (Rasburicase) significantly decrease incidence of tumor lysis syndrome, acute renal failure and dialysis to 10.7% during COP reduction which is similar to what reported before [21] .

Toxic death was not experienced during and immediately after treatment period.

Eighteen percent (18%) of our patients had combined BM and CNS involvement, results of a randomized international study of high-risk central nervous system B Non-Hodgkin lymphoma and B acute lymphoblastic

Table 8. Association of overall survival, demographic and clinical parameters.

leukemia in children and adolescents showed that subgroup of children with combined BM and CNS involvement at diagnosis had a significantly inferior outcome (61%), versus children with BM or CNS only [23] - [30] .

Only one case of death was reported in this study due to disease progression during chemotherapy (case #3) six year old boy with Burkitt’s leukemia with complex karyotyping rearrangements in addition to the IGH/ MYCC rearrangement and combined BM and CNS involvement.

As reported in international studies adverse prognostic factors identified in other studies include high LDH, CNS disease at diagnosis, and slow response to the early phase COP chemotherapy [11] however in our study none of these prognostic factors was found to be significant (P value < 0.05) except CNS involvement which appeared to be the only factor associated with poor outcome (Table 8).

Our study proves that intensive chemotherapy program can overcomes previously recognized risk factors.

5. Conclusions

We feel that the importance of the current study is to document the relative distribution of various types of pediatric non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas and age-specific distribution in different histological subtypes in Saudi Arabia. This study will help to establish a base line for future studies conducted on pediatric Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in KFMC, which will serve as a guideline for the diagnosis, treatment & management and help improve the outcome for children with NHL in Saudi Arabia.

The outcomes in our small series appeared to be excellent compared with those of international trials even though most patients presented in advanced stage of the disease; it provided data about outcomes on fairly advanced lymphomas which was a common mode of presentation in our patients.

Some limitations in our study were the small sample size and retrospective design; future prospective studies with larger sample size are needed to confirm our study’s results.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by Seanad Children Cancer Support Association. The authors are grateful to the expert work of Dr. D.P Edward, Dr. Humariya Heena and MR Mohamed Salman Bashir.

Authorship

Contribution: N.A.M. was the primary author, designed and conducted data interpretation of the study; S.A.T carried out the cytogenetic studies, reviewed and edited the manuscript; W.A.S performed pathology reviews, and reviewed the manuscript; M.A is the department chair who approved the study and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-Interest Disclosure

The authors declare no competing financial interests and no non-financial competing interests.

References

- The Saudi Cancer Registry (SCR). http://www.scr.org.sa

- Perkins, S.L., Segal, G.H. and Kjeldsberg, C.R. (1995) Classification of Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphomas in Children. Seminars in Diagnostic Pathology, 12, 303-313.

- Atra, A., Gerrard, M., Hobson, R., Imeson, J.D., Ashley, S. and Pinkerton, C.R. (1998) Improved Cure Rate in Children with B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (B-ALL) and Stage IV B-Cell Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (B-NHL): Results of the UKCCSG 9003 Protocol. British Journal of Cancer, 77, 2281-2285. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/bjc.1998.379

- Bowman, W.P., Shuster, J.J., Cook, B., Griffin, T., Behm, F., Pullen, J., et al. (1996) Improved Survival for Children with B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia and Stage IV Small Non Cleaved-Cell Lymphoma: A Pediatric Oncology Group Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 14, 1252-1261.

- Brecher, M.L., Schwenn, M.R., Coppes, M.J., Bowman, W.P., Link, M.P., Berard, C.W., et al. (1997) Fractionated Cyclophosphamide and Back to Back High Dose Methotrexate and Cytosine Arabinoside Improves Outcome in Patients with Stage III High Grade Small Non-Cleaved Cell Lymphomas (snccl): A Randomized Trial of the Pediatric Oncology Group. Medical and Pediatric Oncology, 29, 526-533. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-911X(199712)29:6<526::AID-MPO2>3.0.CO;2-M

- Cairo, M.S., Gerrard, M., Sposto, R., Auperin, A., Pinkerton, C.R., Michon, J., et al. (2007) Results of a Randomized International Study of High-Risk Central Nervous System B Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma and B Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Children and Adolescents. Blood, 109, 2736-2743.

- Anon (2000) Cuneo, a Classification of B-cell Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphomas (NHL). Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics in Oncology and Haematology, 4, 24-26. http://AtlasGeneticsOncology.org/Anomalies/BNHLClassifID2067.html

- Dave, B.J., Nelson, M. and Sanger, W.G. (2011) Lymphoma Cytogenetic. Clinics in Laboratory Medicine, 31, 725-761. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cll.2011.08.001

- Harris, N.L., Jaffe, E.S., Stein, H., Banks, P.M., Chan, J.K.C., Cleary, M.L., et al. (1994) A Revised European-Ameri- can Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms: A Proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group. Blood, 84, 1361-1392.

- Murphy, S.B. (1980) Classification, Staging and End Results of Treatment of Childhood Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphomas: Dissimilarities from Lymphomas in Adults. SeminOncol, 7, 332-339.

- Cairo, M.S., Sposto, R. Gerrard, M., Auperin, A., Goldman, S.C., Harrison, L., et al. (2012) Advanced Stage, Increased Lactate Dehydrogenase, and Primary Site, but Not Adolescent Age ( ≥15 Years), Are Associated with an Increased Risk of Treatment Failure in Children and Adolescents with Mature B-Cell Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: Results of the FAB LMB 96 Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30,387-393. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.33.3369

- Reiter, A., Schrappe, M., Tiemann, M., Ludwig, W.D., Yakisan, E., Zimmermann, M., et al. (1999) Improved Treatment Results in Childhood B-Cell Neoplasms with Tailored Intensification of Therapy: A Report of the Berlin-Frank- furt-Munster Group Trial NHL-BFM 90. Blood, 94, 3294-3306.

- Yaqo, R.T., Hughson, M.D., Sulayvani, F.K. and Al-Allawi, N.A. (2011) Malignant Lymphoma in Northern Iraq: A Retrospective Analysis of 270 Cases According to the World Health Organization Classification. Indian Journal of Cancer, 48, 446-451. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0019-509X.92276

- Lowe, E.J. and Gross, T.G. (2013) Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma in Children and Adolescents. Paediatric Hematology-Oncology, 30, 509-519. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/08880018.2013.805347

- Mwanda, W.O., Orem, J., Remick, S.C., Rochford, R., Whalen, C. and Wilson, M.L. (2005) Clinical Characteristics of Burkitt’s Lymphoma from Three Regions in Kenya. East African Medical Journal, 82, S135-S143.

- Ray, S.1., Mallick, M.G. and Pal, P.B., Choudhury, M.K., Bandopadhyay, A. and Guha, D. (2008) Extranodal Non- Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Presenting as an Ovarian Mass. Indian Journal of Pathology and Microbiology, 51, 528-530. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0377-4929.43750

- Miyazaki, N., Kobayashi, Y., Nishigaya, Y. Momomura, M., Matsumoto, H. and Iwashita, M. (2013) Burkitt Lymphoma of the Ovary: A Case Report and Literature Review. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research, 39, 1363-1366. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jog.12058

- El-Hazmi, M.A.F. and Warsy, A.S. (1999) The Pattern for Common Anaemia among Saudi Children. Journal of Tropical Pdiatrics, 45, 221-225. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/tropej/45.4.221

- Jiang, F., Yu, W.-J., Wang, X.-H., Tang, Y.-T., Guo, L. and Jiao, X.-Y. (2014) Regulation of Hepcidin through GDF- 15 in Cancer-Related Anaemia. Clinica Chimica Acta, 428, 14-19.

- Al Sudairy, R., Al Omari, A., Jarrar, M., Al Harbi, T., Al Jamaan, K., Tamim, H. and Jazieh, A.R. (2011) Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use among Pediatric Oncology Patients in a Tertiary Care Center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 29, Article ID: e13011. http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/content/79886-102

- Spreafico, F., Massimino, M., Luksch, R., Casanova, M., Cefalo, G.S., Collini, P., et al. (2002) Intensive, Very Short- Term Chemotherapy for Advanced Burkett’s Lymphoma in Children. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 20, 2783-2788. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2002.08.088

- Patte, C., Auperin, A., Gerrard, M., Michon, J., Pinkerton, R., Sposto, R., et al. (2007) Results of the Randomized International FAB/LMB96 Trial for Intermediate Risk B-Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma in Children and Adolescents: It Is Possible to Reduce Treatment for the Early Responding Patients. Blood, 109, 2773-2780.

- Patte, C., Auperin, A., Michon, J., Behrendt, H., Leverger, G., Frappaz, D., et al. (2001) The Société Française d'Oncologie Pédiatrique LMB89 Protocol: Highly Effective Multiagent Chemotherapy Tailored to the Tumor Burden and Initial Response in 561 Unselected Children with B-Cell Lymphomas and L3 Leukemia. Blood, 97, 3370-3379. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood.V97.11.3370

- Anderson, J.R., Jenkin, R.D., Wilson, J.F., Kjeldsberg, C.R., Sposto, R., Chilcote, R.R., et al. (1993) Long-Term Follow-Up of Patients Treated with COMP Or LSA2L2 Therapy for Childhood Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: A Report of CCG-551 from the Children’s Cancer Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 11, 1024-1032.

- Anderson, J.R., Wilson, J.F., Jenkin, D.T., Meadows, A.T., Kersey, J., Chilcote, R.R., et al. (1983) Childhood Non- Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: The Results of a Randomized Therapeutic Trial Comparing a 4-Drug Regimen (COMP) with a 10-Drug Regimen (LSA2-L2). The New England Journal of Medicine, 308, 559-565. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198303103081003

- Lones, M.A., Perkins, S.L., Sposto, R., Kadin, M.E., Kjeldsberg, C.R., Wilson, J.F., et al. (2000) Large Cell Lymphoma Arising in the Mediastinum in Children and Adolescents Is Associated with an Excellent Outcome: A Children’s Cancer Group Report. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 18, 3845-3853.

- Percy, C.L., Smith, M.A., Linet, M., et al. (1999) Lymphomas and Reticuloendothelial Neoplasms. In: Ries, L.A.G., Smith, M.A., Gurney, J.G., et al., Eds., Cancer Incidence and Survival among Children and Adolescents: United States SEER Program 1975-1995, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Seer Program, NIH Pub. No. 99-4649, 35-50.

- Cairo, M.S., Krailo, M.D., Morse, M., Hutchinson, R.J., Harris, R.E., Kjeldsberg, C.R., et al. (2002) Long Term Follow-Up of Short Intensive Multiagent Chemotherapy without high-Dose Methotrexate (“Orange”) in Children with Advanced Non-Lymphoblastic Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: A Children’s Cancer Group Report. Leukemia, 16, 594- 600. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.leu.2402402

- Cairo, M.S., Sposto, R., Perkins, S.L., Meadows, A.T., Hoover-Regan, M.L., Anderson, J.R., et al. (2003) Burkitt’s and Burkitt-Like Lymphoma in Children and Adolescents: A Review of the Children’s Cancer Group Experience. British Journal of Haematology, 120, 660-670. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04134.x

- Gerrard, M., Cairo, M.S., Weston, C., Auperin, A., Pinkerton, R., Lambilliote, A., et al. (2008) Excellent Survival Following Two Courses of COPAD Chemotherapy in Children and Adolescents with Resected Localized B-Cell Non- Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: Results of the FAB/LMB 96 International Study. British Journal of Haematology, 141, 840-847. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07144.x

NOTES

*Corresponding author.