Natural Science

Vol.06 No.16(2014), Article ID:51269,8 pages

10.4236/ns.2014.616113

About Lorentz Invariance and Gauge Symmetries: An Alternative Approach to Relativistic Gravitation

Richard Bonneville

Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES), 2 Place Maurice Quentin, Paris, France

Email: richard.bonneville@cnes.fr

Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 11 September 2014; revised 26 September 2014; accepted 8 October 2014

ABSTRACT

An alternative presentation of a relativistic theory of gravitation, equivalent to general relativity, is given. It is based upon the restriction of the Lorentz invariance of special relativity from a global invariance to a local one. The resulting expressions appear rather simple as we consider the transformations of a local set of pseudo-orthonormal coordinates and not the geometry of a 4- dimension hyper-surface described by a set of curvilinear coordinates. This is the major difference with the usual presentations of general relativity but that difference is purely formal. The usual approach is most adequate for describing the universe on a large scale in astrophysics and cosmology. The approach of this paper, derived from particle physics and focused on local reference frames, underlines the formal similarity between gravitation and the other interactions inasmuch as they are associated to the restriction of gauge symmetries from a global invariance to a local one.

Keywords:

Gravitation, General Relativity, Gauge Symmetries

1. Introduction

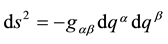

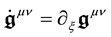

In the usual presentations of general relativity [1] , space-time geometry is described via any set of 4 curvilinear coordinates ; an elementary space-time path

; an elementary space-time path  is expressed as

is expressed as  where the quadratic form

where the quadratic form  characterizes the local metrics. The stake is to express the laws of physics in that frame;

characterizes the local metrics. The stake is to express the laws of physics in that frame;

for example in the absence of other external forces than gravitation, a particle follows the minimum path

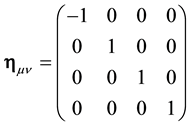

between two space-time points A and B. In the presence of a gravitation field there is no global transformation of the coordinates allowing the  to take in the whole space-time the simple form of a Minkowski metrics; nevertheless it can take this special form in a particular point by a suitable change of coordinates which simply consists in diagonalizing

to take in the whole space-time the simple form of a Minkowski metrics; nevertheless it can take this special form in a particular point by a suitable change of coordinates which simply consists in diagonalizing  in this point [2] .

in this point [2] .

We give here an alternative presentation of a relativistic theory of gravitation, equivalent to general relativity, in which gravitation is introduced as a gauge field associated to restricting the global Lorentz invariance of special relativity to a local one.

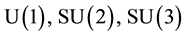

The presentation of gravitation as a gauge field has been first introduced by Lanczos in the context of a variational approach to general relativity [3] [4] . Then it has been highlighted in an extension of the Yang-Mills approach of particle physics [5] - [7] . In the later, the fundamental interactions are accounted for by the restriction of gauge symmetries from a global invariance to a local one [8] . Those interactions (electro-magnetic, weak, strong) are associated to symmetry groups isomorphic to , whose elements are unitary transformations [9] [N.B.: by isomorphism between two groups, we mean that their Lie algebras possess the same commutation relations]. When that approach is applied to gravitation, the equivalence principle, central in general relativity [10] , is not explicitly assumed but rather derived from the fact that the gauge field is supposed to be minimally coupled.

, whose elements are unitary transformations [9] [N.B.: by isomorphism between two groups, we mean that their Lie algebras possess the same commutation relations]. When that approach is applied to gravitation, the equivalence principle, central in general relativity [10] , is not explicitly assumed but rather derived from the fact that the gauge field is supposed to be minimally coupled.

That restriction from a global invariance to a local one, associated to the emergence of a force field, is indeed a deep similarity between gravitation and the other interactions. However the Lorentz group is isomorphic to the special complex linear group  whose elements are not unitary and this is an essential difference between gravitation and the other interactions.

whose elements are not unitary and this is an essential difference between gravitation and the other interactions.

In the present work, we assume that the Lorentz group invariance is not a global symmetry of space-time but a local symmetry of a 4-dimension hyper-surface, which can be thought of as embedded in a space with a larger number of dimensions and we consider the transformations of a local set of pseudo-orthonormal coordinates and not the geometry of the 4-dimension hyper-surface described by a set of curvilinear coordinates. This is a major difference with other presentations of relativistic gravitation; its interest is to lead to facially simpler expressions although that difference is essentially formal.

2. Gauge Properties

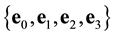

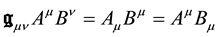

Let us consider the 4-dimension space-time of special relativity and a pseudo-orthonormal base  with the Minkowski metrics

with the Minkowski metrics

(1)

(1)

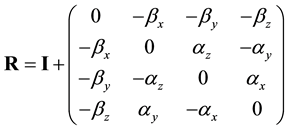

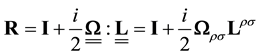

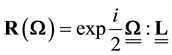

Any infinitesimal transformation R of the Lorentz group can be written as

(2)

(2)

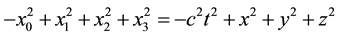

conserves the pseudo norm

conserves the pseudo norm . It can alternatively be written as

. It can alternatively be written as

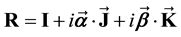

(3)

(3)

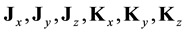

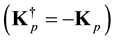

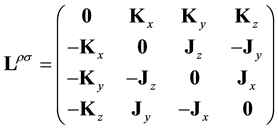

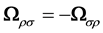

where  et

et

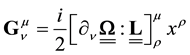

We introduce the 2 anti-symmetric tensors

and

Each component

More generally, any transformation of the Lorentz group can be figured by

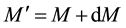

We now assume that the Lorentz group invariance is not a global symmetry of space-time but a local symmetry of a 4-dimension hyper-surface, which can be thought of as embedded in a space with a larger number of dimensions, for example 10 as it is envisaged in many unification theories. If we consider the tangent plane to this hyper-surface in any point M, it is possible to define in this plane a pseudo-orthonormal reference frame, and in fact an infinite set of similar frames deduced from each other by a Lorentz transformation or a rotation; in the close vicinity of M the laws of physics are invariant under the Lorentz group. We can in another point

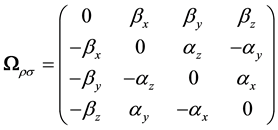

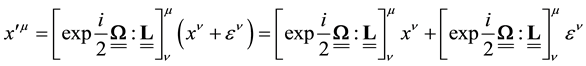

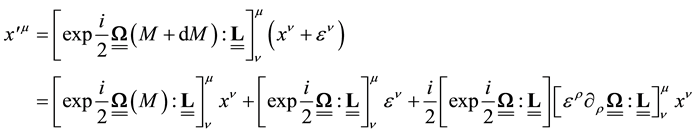

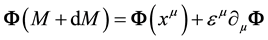

Let us first perform on the surface an infinitesimal displacement

But if

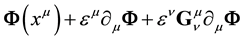

Comparing the two expressions Equation (8) and Equation (9) above, we see that

with

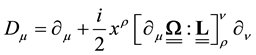

Now considering some function

is in a similar way transformed into

i.e.

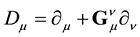

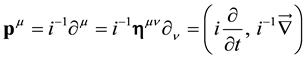

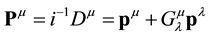

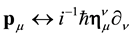

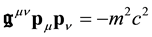

The impulsion

is the infinitesimal generator of space-time translations. Equation (14) above means that

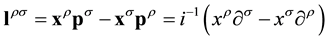

The orbital angular momentum anti-symmetric tensor

can be written as

where

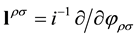

can be written as

That expression allows to evidence a gauge invariance property: it is possible to add to

We have here above considered the transformations of a local set of pseudo-orthonormal coordinates and not the geometry of the 4-dimension hyper-surface described by a set of curvilinear coordinates. This is the major difference with other presentations of relativistic gravitation and notably with general relativity but that difference is purely formal. As a consequence, many mathematical expressions look simpler; for example, the inva-

riant 4-dimension volume element

3. Gravitation Field Equations

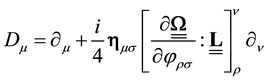

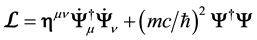

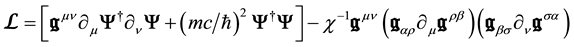

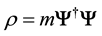

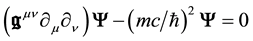

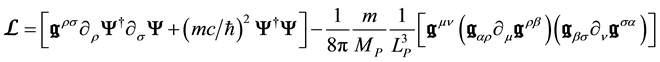

We now consider a scalar particle of mass m (but the procedure can be straightforwardly generalized to a particle of any spin, be it massive or not) and the Lagrangian density

with

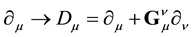

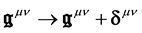

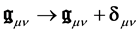

We perform the transformation

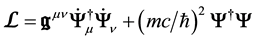

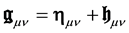

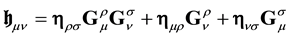

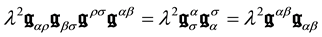

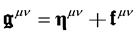

where we have introduced the effective metrics

with

We have written

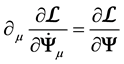

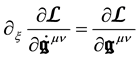

Applying the Lagrange equations to the

gives

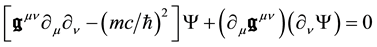

From the expression of

Equation (26) shows that actually

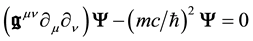

The wave equation so appears as the wave equation of a free particle in which the original Minkowski metrics

The gravitation field is thus described by a modification of the geometry of space-time by replacing the Minkowski metrics

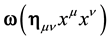

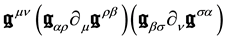

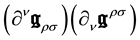

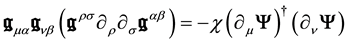

We now assume for the gravitation field itself a Lagrangian density term quadratic in

or

[N.B.: as

The full Lagrangian density of the (field + particle) system is

where

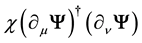

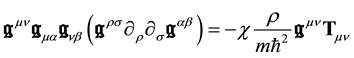

Applying the Lagrange equations to

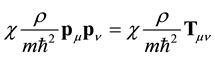

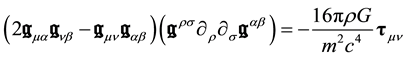

with

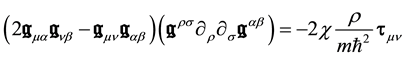

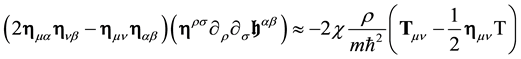

These are the equations of the gravitation field and their nonlinear character is obvious. The term on the right- hand side

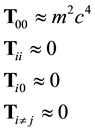

is proportional to the energy-impulsion density tensor of the particle; it is the source term of the gravitation field. In the classical, i.e. non quantum, limit, the correspondence

So Equation (32) becomes

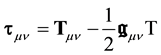

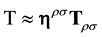

For the sake of commodity, we will re-write it in a different, more workable way. Let us introduce the two quantities

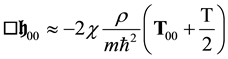

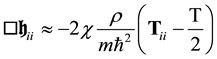

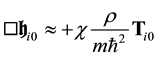

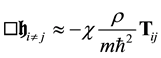

Combining Equations (35) and (36) we finally get after some manipulations

4. Non Relativistic Limit

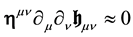

In the case of a weak gravitation field, the quadratic terms in the field equations can be neglected. In the absence of matter, the linearized equations take the form of propagation like equations:

If matter is present, there is a source term:

with

i.e.

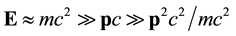

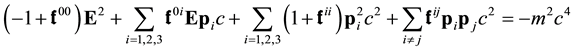

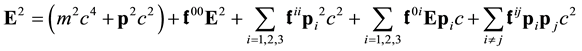

In the non-relativistic limit

hence

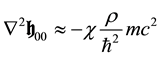

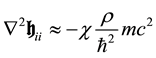

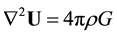

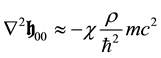

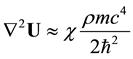

Moreover if the field is slowly varying with time, the time derivatives on the left hand side of Equation (40) vanish and those equations become:

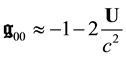

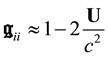

The above expression for

where

On the other hand, the dynamical equation of a massive particle is given by Equation (27)

or

Let us put

so that Equation (44b) becomes

or

Let us also put

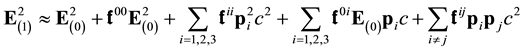

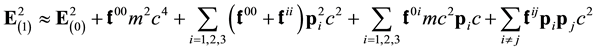

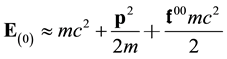

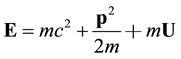

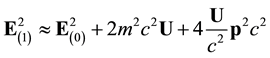

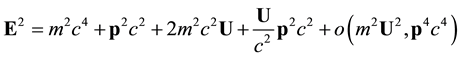

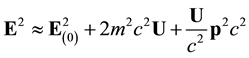

We proceed by successive iterations; replacing

or

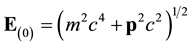

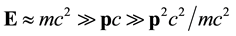

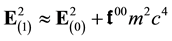

In the non-relativistic limit

Moreover in the weak field limit

If we compare the above expression with the non-relativistic expression

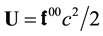

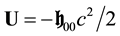

we see that the particle is undergoing an effective gravitation potential

Since

Since from Equation (42a)

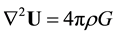

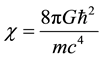

By comparison with the expression of the classical gravitation potential

If we had retained the

5. Post-Newtonian Terms

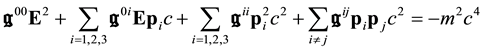

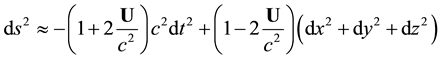

From the expressions Equation (42) we derive in the weak, slowly varying field limit

so that

In addition, Equation (48b) gives

This has to be compared with the Newtonian expression at the lowest order in

or

6. Conclusions

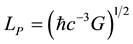

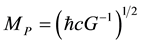

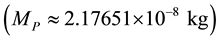

Introducing the Planck length

The usual approach of general relativity is most adequate for describing the universe on a large scale in astrophysics and cosmology. The approach of this paper, derived from particle physics and focused on local reference frames, underlines the formal similarity between gravitation and the other interactions inasmuch as they are associated to the restriction of a global symmetry to a local one.

In a 10-dimension space-time as it is considered in certain unification theories, gravitation is linked to the geometry of the 4 usual dimensions whereas the other fundamental interactions can be associated to the geometry of the 6 additional ones; in that approach extra fields (which eventually may account for dark matter and/or dark energy) naturally come out by regarding the geometry of the full 10-dimension set.

References

- Landau, L. and Lifshitz, E. (1966) Field Theory. Mir Editions, Moscow.

- Weinberg, S. (1972) Gravitation and Cosmology. John Wiley, Hoboken.

- Lanczos, C. (1949) Lagrangian Multiplier and Riemannian Spaces. Reviews of Modern Physics, 21, 497. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.21.497

- Takeno, H. (1964) On the Spin Tensor of Lanczos. Tensor, 15, 103.

- Ivanenko, D. and Sardanashvili, G. (1983) The Gauge Treatment of Gravity. Physics Report, 94, 1-45.

- Lasenby, A., Doran, C. and Gull, S. (1998) Gauge Theories and Geometric Algebra. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, A356, 487-582. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsta.1998.0178

- Blagojevic, M. and Hehl, F.W. (2013) Gauge Theories of Gravitation: A Reader with Commentaries. World Scientific, Singapore. http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/p781

- Becchi, C. (1997) Introduction to Gauge Theories. arXiv:hep-ph/9705211v1

- Mann, R. (2010) An Introduction to Particle Physics and the Standard Model. CRC Press, Boca Raton.

- Roll, P.G., Krotkov, R. and Dicke, R.H. (1964) The Equivalence of Inertial and Passive Gravitational Mass. Annals of Physics, 26, 442-517.