Modern Economy

Vol.05 No.05(2014), Article ID:46031,20 pages

10.4236/me.2014.55045

An Essay on Intra-Industry Trade in Intermediate Goods

Rosanna Pittiglio

Second University of Naples, Capua, Italy

Email: rosanna.pittiglio@unina2.it

Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 6 March 2014; revised 6 April 2014; accepted 16 April 2014

ABSTRACT

This paper contributes to the debate on the effects of international fragmentation on two-way trade in several ways. Firstly, it is the first study on determinants of horizontal and vertical intra- industry trade in intermediate goods with regard to Italy. Secondly, it studies if and how coun- try-specific factors affect intra-industry trade in intermediate goods when heterogeneity among sectors is allowed. The topic is very important for its policy implications. As is known, the early literature distinguishing vertical from horizontal intra-industry trade is especially concerned that their determinants are not the same, and that an expansion in two-way trade might have different adjustment implications depending on its nature. In the case of input trade, the same motivation applies (since intermediates are a subset of total goods traded) but to a greater extent. The analy- sis, on the one hand has produced results that support the theoretical hypotheses, on the other hand has confirmed the relevance of considering intersectoral heterogeneity in analyzing determinants of intra-industry trade in intermediate goods.

Keywords:

Intermediate Goods, Intra-Industry Trade, Homogeneity Hypothesis, Fragmentation

1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, studies on international trade have revealed an increase in the degree of international product fragmentation (i.e. splitting up of a previously integrated production process into two or more compo- nents, or fragments, produced in different countries), as well as a rise in vertical supply chains and the related sourcing strategies of firms—Feenstra [1] ; Hummels et al. [2] ; Yeats [3] ; Kimura and Ando [4] ; Kaminski and Ng [5] ; Ando [6] ; De Backer and Yamano [7] . Firms are increasingly outsourcing and offshoring in order to achieve lower costs and higher quality inputs and, therefore, improve their competitiveness. As a consequence, the exchanges between countries are characterised by a larger share of trade in intermediate goods—i.e. input to the production process that has itself been produced and, unlike capital, is used up in production [8] 1. For in- stance, from 1999 to 2007 the trade growth rate in intermediate goods totalled 80%, whereas today intermediate goods dominate trade flows, representing 56% of total trade [10] .

As occurs with final goods, a substantial part of the trade in intermediate goods takes the form of intra-indus- try trade—the simultaneous export and import of intermediate goods substitutes in production and consumption of other intermediate goods. From 1962 to 2006, world Intra-Industry Trade in Intermediate Goods (henceforth, IG_IIT) increased from around 30% to approximately 60% of total trade by comparison with final goods, for which the increase moved from approximately 25% to 45% of total trade [11] .

The literature on intra-industry trade, both theoretical and empirical, has mainly focused on the exchanges of different varieties of products, without paying attention to intermediate goods, even though in 1975 Grubel and Lloyd had already stressed that countries not only exchanged final goods for final goods, but also final goods for intermediate inputs belonging to the same industry, or even intermediate goods for other intermediate goods within the same industry.

Only recently, some scholars—Jones et al. [13] ; Ando [6] ; Türkcan [14] —have suggested that:

1) The international fragmentation generates a two-way trade in intermediate goods between countries which may exchange intermediate goods for intermediate goods, both within the same industry classification.

2) There are three situations leading to two-way trade in intermediate goods: horizontal trade in similar prod- ucts with differentiated varieties; trade in vertically differentiated goods distinguished by quality; and vertical specialisation involving the exchange of technologically linked products.

From a theoretical point of view, on the one hand, Arndt [15] , Feenstra and Hanson [16] suggest that vertical specialisation in intermediate goods is coherent with the Hecksher-Ohlin model, whereby firms engage in trade in intermediate goods—i.e., each component production requires different factor intensities and is therefore ex- pected to exploit factor cost differences across countries. On the other hand, other authors—Ethier [17] ; Lüthje [18] ; Lüthje [19] —believe that scale economies and product differentiation are able to explain intra-industry trade in horizontally differentiated intermediate goods.

The empirical analyses produced to date have mainly examined the relevance of trade in intermediate goods caused by fragmentation of production (see for instance, Feenstra [1] ; Görg [20] ; Hummels et al. [2] ; Yeats [3] ; Egger and Egger [21] ; Jones et al. [22] ; Kaminski and Ng [5] ; Kimura and Ando [4] ; Kimura et al. [23] ); whereas there have been a limited number of studies regarding IG_IIT (Schuler [24] ; Montout et al. [25] ; Ito and Umemoto [26] ; Umemoto [27] ; Türkcan [28] ; Ando [6] ; Wakasugi [29] ; Türkcan [30] ; Türkcan [14] ; Türkcan and Ates [31] ).

Using finely disaggregated trade data, this paper examines recent changes in trade patterns in the Italian manufacturing sector, by breaking down bilateral two-way trade flows in intermediate goods into vertical and horizontal. In addition, the role of country-specific factors suggested by the theoretical literature on intermediate goods will be tested using panel data techniques. The analysis concerns bilateral trade between Italy and OECD countries over a ten year period.

It should be noted that this is the first study that analyses the determinants of intra-industry trade in interme- diate goods with regard to total Italian manufacturing sector controlling for heterogeneity among sectors when country-specific factors are analyzed. In doing this, we follow the approach proposed by Pittiglio [32] and Pit- tiglio and Reganati [33] who have argued and showed the importance of controlling for sectoral heterogeneity when the determinants of intra-industry trade are investigated. As noted by above cited authors, this aspect can not be ignored since the analysis could produce biased results.

The topic is very important for its policy implications. As is known, the early literature distinguishing vertical from horizontal intra-industry trade is especially concerned that their determinants are not the same, and that an expansion in two-way trade might have different adjustment implications depending on its nature. In the case of input trade, the same motivation applies (since intermediates are a subset of total goods traded) but to a greater extent—for instance, if we consider the effect of a sudden reduction in the two-way trade of input i in industry j; in the case of vertical two-way trade, the reduction in trade of input i corresponds to a loss of output in industry j for other countries involved in stages of production within industry j that use input i. In the case of horizontal intra-industry trade, partner countries’ output losses are likely to be small for other countries since inputs are differentiated but substitutable.

The paper is structured as follows. The next section reviews the main insights obtained from the theoretical and empirical literature on IG_IIT. Section 3 describes the methodology used for identifying intermediate goods and for breaking down intra-industry trade into vertical and horizontal, and provides some stylized facts with re- gard to the distribution of two-way trade in intermediate goods across industries and across partner countries. Section 4 sets out the hypotheses to be tested, the model, and the results of econometric analysis. Finally, Section 5 sums up the main findings of the paper, discussing the implications of the results and drawing some conclusions.

2. A Brief Survey of Intra-Industry Trade Literature in Intermediate Goods

Intra-industry trade in intermediate goods has been little studied in the literature, even though in 1975 Grubel and Lloyd had already begun to perceive this phenomenon, concluding that similarly to intra-industry trade of final goods—differentiated horizontally or vertically—countries could exchange final goods for intermediate in- puts belonging to the same industry or intermediate goods with other intermediate goods—horizontally or verti- cally differentiated.

In a 1987 paper, Greenaway and Milner [34] suggested that two-way trade in intermediate goods was an as- pect of the trade that had not been adequately analysed. Later, Kol and Rayment [35] stated that two-way trade could occur in three different situations: exchange of final goods with final goods; exchange of intermediate goods with intermediate goods; and finally, the exchange of a final good with an intermediate good inside the same industry aggregation.

More recently, Greenaway and Torstensson [36] have again raised this issue, which becomes increasingly complicated if one considers that the horizontal and vertical nature of production differentiation leads to inter- mediate goods trade being distinguished as either horizontal or vertical.

Horizontal intra-industry trade in intermediate goods (IG_HIIT) indicates the simultaneous export and import of goods, which although identical in terms of quality, costs and the techniques of production used, have differ- ent technology characteristics; whereas vertical intra-industry trade in intermediate goods (IG_VIIT) refers to the exchange of inputs belonging to the same industry with a different quality level or located at a different level of the line value [28] .

From a theoretical point of view, the models able to explain these two forms of trade are quite different. Two way trade in horizontally differentiated goods can be explained by scale economies and product differentiation (Ethier [17] ; Lüthje [18] ; Lüthje [19] ).

In modelling the international division of labour, Ethier [17] follows an approach defined in economic litera- ture as the “love of variety for inputs-approach” (symmetrical to the Dixit and Stiglitz “love of variety of final goods”), according to which industries, like consumers, benefit from the existence of variety in those same in- termediate goods.

Lüthje [18] [19] , instead, explains horizontal intra-industry trade in intermediate goods through the “ideal in- termediate good approach”, similar to Lancaster’s “ideal variety approach”. In this case, producers buy only that particular variety of intermediate goods which best satisfies the specific needs of production. As a result, the final goods producer will use a specific variety of intermediate goods i.e. an “ideal intermediate goods” in the production of the specific variety of final goods.

Vertical intra-industry trade models in intermediate goods, on the other hand, date back to the end of the 1990s and early 2000s (see among others: Feenstra and Hanson [16] ; Deardorff, [37] ; Jones and Kierzkowski [38] ). In these models, two-way trade is consistent with the Hecksher-Ohlin model, whereby firms engage in trade in intermediate goods: each component production requires different factor intensities and is therefore ex- pected to exploit factor cost differences across countries. In this case a country could in fact specialise in the production of only one stage of the production process.

From an empirical standpoint, the first studies on intermediate goods date back to the beginning of the 1980s, but they essentially focused on the reasons that could drive a firm to move some phases of its productive process which had previously been integrated in other countries (Helleiner [39] ; and Morawetz [40] can be considered the pioneering studies)2. It is only since the 1990s that a great deal of intellectual effort has been expended in explaining the relevance, characteristics and dynamics of the international fragmentation of production and, therefore, of trade in intermediate goods. By using several approaches and data sources, researchers have found that production processes are becoming increasingly fragmented across national borders, that the degree of fragmentation varies across both countries and industries, and lastly, that the level of fragmentation decreases with the distance between partner countries (see among others, Campa and Goldberg [41] ; Hummels et al. [42] ; Yeats [3] ; Feenstra and Hanson [43] ; Yi [44] ; Ng and Yeats [45] ; Ando and Kimura [46] ). This literature does not however consider any kind of interaction between productive cycle subdivision and intra-industry trade.

To the best of our knowledge, Jones et al. [13] was the first study to highlight the fact that two-way trade might also increase if various fragments of an industry’s productive process were classified in the same industri- al category. By using data on trade flows between NAFTA countries in their empirical analysis, the authors illu- strated not only how the international fragmentation process developed, but also the different consequences that it could generate on the nature of two-way trade in two different industries. To give a specific case, they re- vealed that in the television-producing industry located in the USA and Mexico, for example, intra-industry trade remains at higher levels than in the industry as a whole, while it tends to decrease when the productive process is divided into fragments. Differently, in the motoring industries, the measure associated with intra-in- dustry trade tends to decrease, while intra-industry trade of parts and components shows a significant growth. In subsequent years, other researchers have analysed the impact of the international fragmentation of production on intra-industry trade, but always with regard to parts and components (Montout et al. [25] ; Ito and Umemoto [26] ; Umemoto [27] ; Ando [6] ; Wakasugi [29] ; Türkcan [30] ; Türkcan and Ates [31] ; Türkcan [14] ).

As noted by Hummels et al. [2] and Türkcan [28] , this approach can be considered appropriate only for sec- tors in which an extremely detailed classification is available (for example “Machinery and Transport Equip- ment Group”—identified with the 7 SITC code in Standard International Trade Classification), otherwise there is a risk that the phenomenon will be underestimated3. This explains why these studies are limited to only a few sectors.

As far as we know, only Türkcan [28] examined this aspect for total manufacturing sectors, with an analysis of the bilateral trade of intermediate goods between the United States and 25 OECD countries over the period 1990-1996. By dividing total intra-industry trade into horizontal and vertical, the author found that, as with final goods, the determinants of vertical and horizontal two-way trade in intermediate goods tend to differ. The author also finds that the differences in technology and foreign direct investments are the principal factors in explaining vertical intra-industry trade, whereas foreign direct investments, similarity in human capital endowments and geographic proximity are the principal factors in explaining horizontal intra-industry trade.

It should be noted that one shortcoming of the above-mentioned empirical studies is the assumption of homo- geneity between sectors when country-specific factors are examined (i.e. country characteristics are considered invariant across industries). As Pittiglio [32] and Pittiglio and Reganati [33] showed with regard to their two analyses on intra-industry trade, if this aspect is not considered, the estimates could provide distort results since the differences in terms of factorial endowments among industries would be overlooked. In other words, and as observed by the authors when we consider, for example, differences in factor endowments, market size or other country specific characteristics as determinants of two-way trade as suggested by the theoretical models, we cannot ignore that these same characteristics also vary among industries: i.e. differences in factor endowments change not only among countries but also across sectors within the same country. Therefore, we believe that this aspect cannot be ignored in our analysis on intermediate goods.

3. Methodological Strategy and Descriptive Analysis

In this section, we examine the extent, nature and evolution over time of IG_IIT between Italy and its main OECD trading partners. In so doing, first, we provide a detailed description of the strategy used to identify goods that can be considered to be intermediate (Section 3.1). Second, we introduce the unadjusted intra-indus- try trade index developed by Grubel and Lloyd [12] and explain its use as the dependent variable for our em- pirical analysis (Section 3.2). Finally, we describe some stylised facts regarding the specific data we use in the empirical study of two-way trade in intermediate goods between Italy and its major OECD partner countries  over time

over time  (Section 3.3).

(Section 3.3).

The partner countries considered are Belgium, Canada, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Ger- many, Japan, the United Kingdom, Spain, Sweden and the United States. These countries are most representa- tive, accounting for about 3/4 of the total volume of Italian trade with OECD countries4.

3.1. Empirical Definition of Intermediate Goods

The selection of goods that can be considered as intermediates is complicated by the fact that there are three dif- ferent approaches in the empirical literature to the identification of intermediate goods, each with advantages and disadvantages.

The first and most common approach to identifying intermediate goods was pioneered by Yeats [3] and pur- sued in a number of recent studies5. This approach consists of considering as intermediates all goods classified as “parts” and “components”. It should be noted that, on the one hand, this method provides comprehensive and consistent coverage of the parts and components trade encompassing a large number of countries. On the other, it suffers from two major limitations that are very closely linked to one another: first, the coverage is limited to parts and components that can be directly identified based on the commodity nomenclature of the US Standard International Trade Classification (SITC) system. These items are confined to the product classes of machinery and transport equipment (SITC 7) and miscellaneous manufactured articles (SITC 8). However, there is evi- dence that a high share of intermediate goods is also present in other product categories, such as pharmaceutical and chemical products (SITC 5), and machine tools and various metal products (SITC 6). Second, this approach limits intermediates trade solely to that containing “parts of” or “component of” in the product description. It should be noted that the use of this approach could thus underestimate the phenomenon, since parts and compo- nents embrace only a share of total trade in intermediate goods. Despite these shortcomings, the approach has been used in the studies (some of which are mentioned above) that provide some indication of the pattern and growth of intra-industry trade over the years.

An alternative approach to estimating trade in intermediate goods was originally proposed by Feenstra and Hanson [50] who recommend using input-output tables. In this case, trade in intermediate goods is measured by combining data on total imports with data from input-output tables to determine the extent of an industry’s pur- chases of intermediate inputs from overseas suppliers.

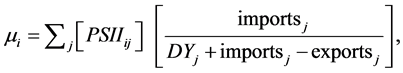

More specifically, for each industry i Feenstra and Hanson [50] constructed the measure

(1)

(1)

where PSII is purchases of intermediate inputs (industry i from industry j), DY is domestic output of industry j, and thus the subscripts j and i refer to industries such that j supplies an input to i . In Equation (1) each product term is interpreted as industry i’s estimate of imported material inputs from industry j.

. In Equation (1) each product term is interpreted as industry i’s estimate of imported material inputs from industry j.

A shortcoming of the above method is that the underlying assumption, according to which total import share is a reasonable proxy for estimating the import share of intermediate inputs, may be flawed. In fact, at the high level of supplier industry aggregation at which these measures are commonly constructed, total imports and total domestic supply encompass imports and output of both intermediate and non-intermediate goods. In this way, the import share in domestic supply of all goods used in Equation (1) may in fact over or underestimate the im- port share in domestic supply of solely intermediate goods. As a result, the measurement error introduced in Equation (1) may potentially be very large. A number of studies have used the Feenstra and Hanson [50] meas- ure of imported intermediates to determine the extent and characteristics of trade in intermediate goods and, above all, to measure the characteristics of vertical fragmentation of production6. It is however worth noting that this method is also subject to a major limitation since input-output tables are typically released every five years and thus annual series cannot be constructed with accuracy.

Finally, the third approach, which has been more frequently used in recent years7, considers as intermediates all goods classified as such by the United Nations Broad Economic Categories (UN BEC classification). The UN BEC classification disentangles goods according to their main end use, and then divides them into capital goods (categories 41 and 521), consumption goods or final goods (categories 112, 122, 522 and 6), and interme- diate goods (categories 111, 121, 2, 3, 42 and 53). These are three basic classes of goods in the System of Na- tional Accounts (SNA)8. It should be noted that an unavoidable drawback of UN BEC is that the allocation of commodities according to their main use is based on “expert judgment”, which is subjective by nature. Many goods may be both final and intermediate depending on the context, for example the food products or fuel iden- tified in UN BEC classification by codes 112 and 122, and 3, respectively.

Hummels et al. [2] state that “Using annual trade data and the United Nations Broad Economic Categories classification scheme, we find that, for the OECD, both the intermediate goods share of imports and of exports declined steadily from about 1970 to 1992. Measuring the intermediate share of imports using the OECD Input- Output Database (OECD) also reveals a declining share during this period. However Yeats (1998) shows that parts and components trade, a subset of intermediate goods trade, has grown as a share of total trade.” (Hum- mels et al., [2] , p. 76, footnote 3).

As noted above, all three methods have their strengths and weaknesses, and we have chosen to use the UN BEC classification in this study because in our analysis we shall use annual observations for all manufacturing sectors; the first method confines the observations merely to the product classes of machinery and transport equipment as identified by code 7 or 8 of SITC. With regard to IO tables, the UN BEC classification also per- mits an analysis of bilateral trade patterns in intermediate goods at a highly disaggregated level9.

3.2. Methodology Used for Calculating the Intra-Industry Trade Index

After identifying intermediate goods, we use an approach common to the analyses on intra-industry trade in in- termediate goods used by Brülhart [56] and Türkcan [30] , to measure the share of intra-industry trade on total trade in intermediate goods and differentiate between its vertical and horizontal components.

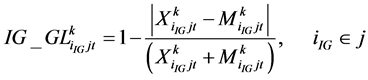

This approach is very similar to the one used by most researchers with regard to total goods (for instance, Greenaway et al. [60] - [62] ; Rodas-Martini [63] ; Crespo and Fontoura [64] ; Reganati and Pittiglio [65] ; Leitão et al., [66] ; Pittiglio [32] ), and supposes firstly, the calculation of the standard Grubel and Lloyd [12] index to the values of Italian exports and imports of intermediate goods for each industry; secondly, the decomposition of the GL index into IG_HIIT and IG_VIIT.

Given this premise, the standard Grubel and Lloyd index in intermediate goods (hereafter, IG_GL) between Italy and its 12 major OECD countries  over time

over time  is calculated as follows:

is calculated as follows:

(2)

(2)

where  and

and  are, respectively, the values of Italian exports and imports of intermediate goods

are, respectively, the values of Italian exports and imports of intermediate goods

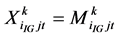

in industry j in a specific year t to and from country k. This measure takes values between zero (complete inter- industry trade) and one (symmetric intra-industry trade), and increases in the share of two-way trade. More spe-

cifically, when  or

or  and there is no overlap of exports and imports of intermediate good

and there is no overlap of exports and imports of intermediate good  in industry j then

in industry j then  is zero. Alternatively, if

is zero. Alternatively, if  and there is complete matching, then

and there is complete matching, then  is unity.

is unity.

Following the prevalent literature on the topic, the IG_GL index has been calculated using data from OECD (International Trade by Commodities Statistics—ITCS) at the 6-digit level of harmonized system (HS) trade classifications (about 3200 items) to avoid the categorical aggregation problem. Intra-industry trade at industry level has been measured by aggregating the above calculated IG_GL indices at 6-digit HS level in each 2-digit manufacturing industry j according to the ISIC Rev. 2 classification as follows:

The IG_GL for Italy as a whole with the partner country k

where the weights

and satisfy the following condition:

As commonly occurs in intra-industry trade literature on final goods, IG_IIT is divided into IG_HIIT and IG_VIIT by comparing unit values of exports relative to imports. In a similar way, this method has also been adopted by several recent papers including Schüler [24] , Montout et al. [25] , Ito and Umemoto [26] , Umemoto [27] , Ando [6] , Wakasugi [29] . Therefore, trade flows between two countries are classified as horizontal two-way trade when the unit value of exports relative to the unit value of imports lies within a specified range. Conversely, if the relative unit values lie outside this range, intra-industry trade is considered to be vertical. It should be noted that in the latter case, this form of trade may capture not only trade in intermediate goods with different quality, but also trade in technologically linked intermediate goods10. This distinction is important be- cause, as seen in Section 2, the determinants of the two types of two-way trade are different11.

Therefore, using the same technique as that suggested by Abd-el-Rahman [67] and Greenaway et al. [61] , and assuming that the unit value of exports

where the parameter a is a dispersion factor that is fixed to reflect the relevant range, a = 0.15 or a = 0.25 being the most widely used in the literature. According to this criterion, when

For each industry j and for each partner country k, we can therefore calculate the following index:

In Equation (8), iIG refers to the above defined 6-digit HS intermediate products in each 2-digit industry, j is a subscript for the 2-digit industry, k is the partner country considered, t the time and p varies according to the na- ture of trade flows (horizontal or vertical).

3.3. Recent Trends in Intra-Industry Trade in Intermediate Goods

Table 1 and Table 2 report some stylised facts with regard to two-way trade in intermediate goods between It- aly and the selected OECD trading partners over the period 1997 to 2006. It should be noted that in these tables IG_GL, IG_HIIT, and IG_VIIT have been compared with two-way trade in total goods (GL, HIIT, and VIIT, re- spectively) as measured in Equations (2)-(8) but considering all items i = (iCG, iFG, iIG)13.

On average, total and vertical two-way trade in intermediate goods is greater than its correspondents for total goods (Table 1). The cross-country variation in two-way trade for all kinds of goods is in line with the expectations, with the highest overall figures being recorded for Italy’s trade with partner countries that are closer in geographical position and in terms of factor endowments (Germany, France, UK, Spain).

The most striking feature of Table 1 is, however, the increased importance of

To investigate whether the situation outlined above changes across sectors, Table 2 shows that the level of Italian

4. Empirical Strategy and Regression Results

In this section we use the hypotheses proposed by Ethier [17] , Feenstra and Hanson [16] , Krugman and Ve- nables [70] , Venables [71] and Hummels et al. [2] to analyse empirically the determinants of Italian intra-in- dustry trade in intermediate goods.

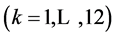

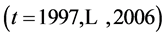

As explained in Section 2, these hypotheses will be differentiated according to the nature of two-way trade and the focus will be on horizontal versus vertical intra-industry trade. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first analysis that has used this approach for Italy. The choice of the country in this exercise is of interest be- cause, as documented by OECD statistics, its use of imported intermediate goods for exports accounts for about 35 percent of its total exports. The second innovative aspect of the research is that we estimate the model by al- lowing sectors to be heterogeneous, i.e., we allow for the effects of country characteristics to vary across indus- tries. Our empirical analysis is conducted over a period of ten years

We shall therefore use the regression equation

where

Table 1. Geographical distribution of Italian intra-industry trade indices in total and intermediate goods(*) (average 1997-2006).

Source: author’s calculations based on OECD data, (1)GL, HIIT, and VIIT calculated by con- sidering all items i = (iCG, iFG, iIG), (2)IG_GL, IG_HIIT, and IG_VIIT calculated by considering only intermediate goods. *Percentages of GL in italics.

Since these indices lie between 0 and 1, which imposes a severe restriction on the disturbance term ε, we let

The list of the explanatory variables that appear in vector

Market Size (SIZE): Market size affects horizontal and vertical intra-industry trade in intermediate goods in different ways. For example, with regard to IG_HIIT, Ethier [17] argues that since the international division of labour is limited by the extent of the market, in free trade, producers of components will be able to use increas-

Table 2. Sectorial distribution of Italian intra-industry trade in intermediate and total goods(*), (average 1997-2006).

Source: author’s calculations based on OECD data, (1)GL, HIIT, and VIIT calculated by considering all items i = (iCG, iFG, iIG), (2)IG_GL, IG_HIIT, and IG_VIIT calculated by considering only intermediate goods. *Percentages of GL in italics.

ing scale economies and thus increase the number and production of intermediate goods. As a result, a country with a small domestic market will have limited opportunities to take advantage of economies of scale in the production of differentiated intermediate goods. Thus, the larger the international market, the larger the oppor- tunities for production of differentiated intermediate goods and the larger the opportunities for trade in interme- diate goods will be. With regard to IG_VIIT, Hummels et al. [2] state that small countries engage more than large countries in vertical trade because, due to their scale, they produce relatively fewer intermediates and im- port a larger number of inputs that are used in their exports14. Moreover, in Feenstra and Hanson’s model, any reduction in the home country’s unit costs due to greater economies of scale will lead to a decline in the usage of imported intermediate goods in the production of final goods. Finally, Jones and Kierzkowski [22] argue that two-way trade in intermediate goods tends to increase with the bilateral market size of the two countries, due to economies of scale in service link activities. As a result, we can expect that the greater the SIZE, (a) the larger IG_HIIT will be and (b) the smaller/the greater IG_VIIT will be.

Differences in Research and Development (DIFRD): The technology gap can be considered one of the most important factors influencing intra-industry trade in general, and in intermediate goods, in particular. This is because variety in intermediates is closely related to the intensity of research and development. Since, in Ethier’s model, differences in factor endowments reduce the extent of horizontal intra-industry trade, we would specifically expect that the greater the DIFRD, the smaller IG_HIIT will be. On the other hand, since in the out- sourcing model an increase in differences in factor endowments in the home country from those in the foreign country increases vertical specialisation, it is plausible to expect that the greater the DIFRD, the larger IG_VIIT will be.

Differences in Factor Endowments (DIFYP): Ethier [17] states that countries with a greater divergence in factor endowments have a lower volume of two-way trade in horizontally differentiated goods. Alternatively, from the model of outsourcing developed by Feenstra and Hanson [16] , we would expect vertical intra-industry trade in intermediate goods to be more likely to take place between countries with dissimilar factor endowments. Türkcan [14] claims that differences in per-capita GDP may also capture the differences in infrastructure en- dowment and worker skills between countries, which would be reflected in lower shares of vertical intra-indus- try trade. As a consequence, the relationship between IG_VIIT and DIFYP remains ambiguous and depends on which of the above effects dominates.

Difference in market size (DIFY): Differences in market size are expected to affect IG_HIIT and IG_VIIT in different ways. In fact, in the context of horizontal differentiation, the difference in market size is considered to be an obstacle to two-way trade [17] . In contrast, Grossman and Helpman [74] show that, in the context of ver- tical differentiation, a trading partner’s market size encourages greater degrees of fragmentation between the trade partners. Firms are more likely to find a trading partner with the appropriate skills that match their needs in large host markets. This suggests a negative relationship between bilateral trade in intermediate goods and dif- ferences in market size. On the other hand, there are also reasons to believe that large markets are more likely to be served by local producers, which should reduce the country’s dependence on imports. Consequently, while the impact of DIFY on IG_VIIT remains ambiguous, we would expect it to affect IG_HIIT negatively.

Distance (DIST): It is commonly agreed that any kind of trade restriction reduces the volume not only of total trade, but also of intra-industry trade. In fact, in the literature on intra-industry trade, the geographical distance which is used as a proxy of transportation cost is found to have a stronger effect on two-way trade than on one-way trade. This is claimed to be due to the fact that differentiated products have a higher degree of substitu- tion than homogeneous goods [75] . It is plausible to expect this to apply to intermediate goods too, and in fact, in this context Krugman and Venables [70] and Venables [71] find that the lower the transportation cost between countries is, the greater the volume of trade between them will be. As a consequence, the shares of horizontal and vertical intra-industry trade in intermediate goods are expected to be negatively associated with distance. Jones [76] also states that a reduction in service-link costs should stimulate the international fragmentation of production across countries. We therefore expect DIST to affect both IG_VIIT and IG_HIIT negatively, and to have a greater impact on the former.

Table 3 summarises the variables used, their expected signs and statistical sources.

Since there are several types of panel analytic models—Pooled Ordinary Least Squares (POLS), Fixed Effects Models (FEM) and Random Effects Models (REM), different tests have been performed to select the right esti- mator for the model.

Table 4 provides the estimates of Equation (9) for two different classifications of intermediate goods—verti- cally and horizontally differentiated intermediate goods—produced by the same industry. For both cases, column (1) provides the estimates based on the POLS, which assumes that the unobservable individual effects are not present, whereas columns (2) and (3) report the estimates based on fixed effects and random effects specifications, respectively.

As it can be noted, the results obtained for both IG_VIIT and IG_HIIT, tell us that the OLS estimator is bi- ased and inconsistent and, therefore, we accept the presence of the individual effects. Moreover, when we run the Hausman test to decide whether we have a REM or FEM, we find that the null hypothesis which assumes

Table 3. Summary information on determinants of two-way trade in intermediates15.

(*)IG_VIIT and IG_HIIT have been measured by using OECD International Trade by Commodities Statistics (ITCS).

Table 4. Coefficient estimates for Equation (9).

*Modified Wald test for groupwise heteroscedasticity in fixed effect regression model. t statistics are in parentheses.

that the REM is more efficient (has smaller asymptotic variance) than the FEM is rejected at the 1% level only for IG_VIIT. We therefore conclude that the FEM is more appropriate for IG_VIIT, whereas a REM is more appropriate for IG_HIIT16.

Finally, the Wald test for groupwise heteroscedasticity rejects the null hypothesis of homoscedasticity in both cases. We therefore present estimation results for the preferred method with heteroscedasticity adjusted errors [77] in Table 5 and Table 6. These are largely in line with the theoretical expectations outlined above and the estimated coefficients support the view that the determinants of IG_VIIT and IG_HIIT are not the same. In par- ticular:

Table 5. Coefficient estimates for Equation (9).

Heteroscedasticity-robust t statistics are in parentheses.

Table 6. Coefficient estimates for Equation (9).

Heteroscedasticity-robust t statistics are in parentheses.

1) SIZE has a positive significant influence on IG_VIIT indicating that a greater level of market size promotes a greater degree of fragmentation due to increasing returns to scale in service link activities. This finding is in line with the earlier works on manufacturing by Jones et al. [73] with regard to the world as a whole and also for NAFTA, EU15 and East Asia, and the study by Kimura et al. [23] for manufacturing in East Asia and Europe. In line with the theoretical hypothesis reported above, the same variable also exerts a positive and statistically significant impact on IG_HIIT.

2) DIFRD appears to have no statistically significant impact on either type of two-way trade. We do not therefore, find any evidence to support the hypothesis that the technology gap between Italy and its partner countries might affect two-way trade in intermediate goods.

3) DIFYP appears to have a positive and statistically significant influence on IG_VIIT, supporting Feenstra and Hanson’s predictions according to which two-way trade in differentiated intermediate goods is stimulated by dis- similar factor endowments. On the other hand, IG_HIIT appears to be weakly and negatively influenced by dif- ferences in factor endowments, supporting the view that a greater divergence in factor endowments yields a lower volume of two-way trade in intermediates. Türkcan [28] obtained similar results with regard to IG_VIIT in his study on the relationship between the US and OECD countries; whereas the researcher found no such evidence with regard to IG_HIIT.

4) DIFY, representing the difference in size between trading partners, exerts a negative and highly significant impact on both IG_VIIT and IG_HIIT. This finding is, on the one hand, consistent with the predictions of both Helpman and Krugman’s models [78] and those of Feenstra and Hanson [16] regarding the volume of vertical trade or outsourcing; on the other hand, it confirms the prediction made by Ethier’s model that a larger difference in market size is an obstacle to horizontal two-way trade in intermediates.

5) DIST appears to have a negative and significant relationship with both concepts of IG_IIT. According to this result, transportation costs significantly hamper fragmentation across countries, confirming the hypothesis developed by both Jones and Kierzkowski [76] that cross-border outsourcing is more favourable if service link costs are lowered, and also Krugman and Venables [70] and Venables [76] . The results are, however, inconsis- tent with the view that the cost of transportation matters more for vertical than horizontal intra-industry trade.

5. Conclusions

In recent years, many studies have observed that an important aspect of globalisation is the growing amount of trade in intermediate goods as a consequence of the process of production relocation. Similarly to final goods, exchanges in intermediate goods have assumed both an inter- and intra-industry nature and, with regard to two-way components, a vertical and horizontal nature. As the theory suggested (Ethier [17] ; Luthje [18] ; Luthje [19] ; Feenstra and Hanson, [16] ), both the determinants, and the policy implications differ across markets where two-way trade prevails.

Given these facts, in this study we have divided total intra-industry trade in intermediate goods into vertical and horizontal two-way trade. The analysis has regarded the Italian bilateral trade with a sample of OECD coun- tries over a ten-year period. Our results suggest that on average total and vertical two-way trade in intermediate goods is greater than its correspondents for total goods. Moreover, in line with the expectations, the highest overall figures are recorded between Italy and those partner countries that are closer in geographical position and in terms of factor endowments.

We therefore estimated a model which incorporates country-specific factors to establish whether these are re- lated to the pattern of horizontal and vertical intra-industry trade. In this case, the determinants of Italian intra- industry trade in horizontally and vertically differentiated intermediate products were analysed by using a data- set which removes the hypothesis that considers the effects of country characteristics on the intra-industry trade specialization index, invariant across industries. The present paper has been motivated by the observation of a gap in the empirical literature on intra-industry trade: the non-consideration of heterogeneity between sectors when country-specific determinants are examined. We believe that this is a strong assumption and its acceptance could bias the results of analyses on intra-industry trade determinants.

The panel data analysis has produced results that largely support the hypotheses drawn from the theoretical models. More specifically, as expected, vertical intra-industry trade in intermediate goods will grow with the difference in factorial endowments and difference in R&D, confirming the results present in Feenstra and Han- son [16] . Moreover, the distance variable, proxy for transport costs, exerts a negative impact on vertical intra- industry trade in intermediate goods, confirming the status according to which transportation costs significantly hamper fragmentation across countries. Finally, as expected, the participation in regional agreements increases trade in intermediate goods. With regard to horizontal components, the estimation results also largely support the theoretical hypotheses drawn from Ethier’s model. In this case, horizontal intra-industry trade increases with the similarity between countries and larger market size, whereas it decreases with differences in country size and distance.

References

- Feenstra, R.C. (1998) Integration of Trade and Disintegration of Production in the Global Economy. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 12, 31-50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/jep.12.4.31

- Hummels, D., Ishii, J. and Yi, K. (2001) The Nature and Growth of Vertical Specialization in World Trade. Journal of International Economics, 54, 75-96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(00)00093-3

- Yeats, A.J. (2001) Just How Big Is Global Production Sharing? In: Arndt, S.W. and Kierzkowski, H., Eds., Fragmentation. New Production Patterns in the World Economy, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 108-143.

- Kimura, F. and Ando, M. (2005) Two-Dimensional Fragmentation in East Asia: Conceptual Framework and Empirics. International Review of Economics and Finance, 14, 317-348.

- Kaminski, B. and Ng, F. (2005) Production Disintegration and Integration of Central Europe into Global Markets. International Review of Economics and Finance, 14, 377-390. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2004.12.008

- Ando, M. (2006) Fragmentation and Vertical Intra-Industry Trade in East Asia. North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 17, 257-281. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.najef.2006.06.005

- De Backer, K. and Yamano, N. (2012) International Comparative Evidence on Global Value Chains. OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Paper, 2012/3.

- Deardorff, A.V. (2006) Terms of Trade: Glossary of International Economics. World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd., Singapore.

- Miroudot, S., Lanz, R. and Ragoussis, A. (2009) Trade in Intermediate Goods and Services. OECD Trade Policy Working Paper, 93.

- OECD (2010) Trade and the Economic Recovery: Why Open Markets Matter. OECD, May 2010.

- World Bank (2009) World Development Report. 2009. Reshaping Economic Geography World Bank.

- Grubel, H. and Lloyd, P.J. (1975) Intra-Industry Trade: The Theory and Measurement of International Trade in Differentiated Product. Macmillan, London.

- Jones, R.W., Kierzkowski, H. and Leonard, G. (2002) Fragmentation and Intra-Industry Trade. In: Lloyd, P.J. and Lee, H.H., Eds., Frontiers of Research in Intra-Industry Trade, Palgrave McMillan, New York, 67-86.

- Türkcan, K. (2011) Vertical Intra-Industry Trade and Product Fragmentation in the Auto-Parts Industry. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, 11, 149-186. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10842-010-0067-0

- Arndt, S.W. (1997) Globalization and the Open Economy. North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 81, 71- 79. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1062-9408(97)90020-6

- Feenstra, R.C. and Hanson, G.H. (1997) Foreign Direct Investment and Relative Wages: Evidence from Mexico’s Maquiladoras. Journal of International Economics, 42, 371-439. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(96)01475-4

- Ethier, J. (1982) National and International Returns to Scale in the Modern Theory of International Trade. American Economic Review, 72, 389-405.

- Lüthje, T. (2000) Intra-Industry Trade in Intermediate Goods. Economic Discussion Papers, University of Southern Denmark, 9.

- Lüthje, T. (2000) Foreign Trade in Differentiated Intermediate Goods. Economic Discussion Papers, University of Southern Denmark, 10.

- Görg, H. (2000) Fragmentation and Trade: US Inward Processing Trade in the EU. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 136, 403-422. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02707287

- Egger, H. and Egger, P. (2005) The Determinants of EU Processing Trade. The World Economy, 28, 147-168. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2005.00679.x

- Jones, R., Kierzkowski, H. and Lurong, C. (2005) What Does the Evidence Tell Us about Fragmentation and Outsourcing. International Review of Economics and Finance, 14, 305-316. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2004.12.010

- Kimura, F., Takahashi, Y. and Hayakawa, K. (2007) Fragmentation and Parts and Components Trade: Comparison between East Asia and Europe. North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 18, 23-40. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.najef.2006.12.002

- Schuler, M.K. (1995) On Intra-Industry Trade in Intermediates. Economia Internazionale, 48, 67-84.

- Montout, S., Mucchielli, J.L. and Zignago, S. (2002) Horizontal and Vertical Intra-Industry Trade of NAFTA and MERCOSUR: The Case of the Automobile Industry. Région et Développement, 16. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2350981

- Ito, K. and Umemoto, M. (2004) Intra-Industry Trade in the ASEAN Region: The Case of Automotive Industry. ICSEAD Working Paper Series, 2004-23.

- Umemoto, M. (2005) Development of Intra-Industry Trade between Korea and Japan: The Case of Automobile Parts Industry. CITS Working Paper Series, 2005-03.

- Türkcan, K. (2005) Determinants of Intra-Industry Trade in Final Goods and Intermediate Goods between Turkey and Selected OECD Countries. Ekonometrive Ýstatistik Say, 1.

- Wakasugi, R. (2007) Vertical Intra-Industry Trade and Economic Integration in East Asia. Asian Economic Papers, 6, 26-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/asep.2007.6.1.26

- Türkcan, K. (2009) Vertical Intra-Industry Trade: An Empirical Examination of the Austria’s Auto-Parts Industry. FIW Working Paper Series, 030.

- Türkcan, K. and Ates, A. (2011) Vertical Intra-Industry Trade and Fragmentation: An Empirical Examination of the US Auto-Parts Industry. The World Economy, 34, 154-172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2010.01316.x

- Pittiglio, R. (2012) Horizontal and Vertical Intraindustry Trade: An Empirical Test of the “Homogeneity Hypothesis”. The World Economy, 35, 919-945. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2012.01471.x

- Pittiglio, R. and Reganati, F. (2012) Vertical Intra-Industry Trade in Higher and Lower Quality: A New Approach of Measuring Country Specific Determinants. International Journal of Economics and Business Research, 4, 44-62.

- Greenaway, D. and Milner, C. (1987) Intra-Industry Trade: Current Perspectives and Unresolved Issues. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv/Review of World Economics, 123, 39-57.

- Kol, J. and Rayament, P. (1989) Allyn-Young Specialisation and Intermediate Goods in Intra-Industry Trade. In: Tharakan, P.K.M. and Kol, J., Eds., Intra-Industry Trade: Theory, Evidence and Extensions, St. Martin’s Press, New York.

- Greenaway, D. and Torstensson, J. (1997) Back to the Future: Taking Stock on Intra-Industry Trade. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv/Review of World Economics, 133, 249-269.

- Deardorff, A.V. (2001) Fragmentation in Simple Trade Models. North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 12, 121-137. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1062-9408(01)00043-2

- Jones, R.W. and Kierzkowski, H. (2001) A Framework for Fragmentation. In: Arndt, S.W. and Kierzkowski, H., Eds., Fragmentation. New Production Patterns in the World Economy, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 17-34.

- Helleiner, G. (1981) Intra-Firm Trade and Developing Countries. Macmillan Press, London.

- Morawetz, D. (1981) Why the Emperor’s New Clothes Are Not Made in Colombia. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Campa, J.M. and Goldberg, L. (1997) The Evolving External Orientation of Manufacturing Industries: Evidence from four Countries. NBER Working Papers, 5919.

- Hummels, D., Rapoport, D. and Yi, K. (1998) Vertical Specialization and the Changing Nature of World Trade, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic Policy Review.

- Feenstra, R.C. and Hanson, G.H. (2003) Global Production Sharing and Rising Inequality: A Survey of Trade and Wages. In: Choi, K. and Harrigan, J., Eds., Handbook of International Trade, Basil Blackwell, London. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9780470756461.ch6

- Yi, K.M. (2003) Can Vertical Specialization Explain the Growth of World Trade? Journal of Political Economy, 111, 52-102. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/344805

- Ng, F. and Yeats, A. (2003) Production Sharing in East Asia: Who Does What for Whom and Why? World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 2197.

- Ando, M. and Kimura, F. (2007) Fragmentation in Europe and East Asia: Evidences from International Trade and FDI Data. In: Ruffini, P.B. and Kim, J.K., Eds., Corporate Strategies in the Age of Regional Integration, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA.

- Athukorala, P. (2005) Product fragmentation and Trade Patterns in East Asia. Asian Economic Papers, 4, 1-27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/asep.2005.4.3.1

- Kimura, F. (2006) International Production and Distribution Networks in East Asia: Eighteen Facts, Mechanics, and Policy Implications. Asian Economic Policy Review, 1, 326-344. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-3131.2006.00039.x

- Athukorala, P. and Yamashita, N. (2008) Patterns and Determinants of Production Fragmentation in World Manufacturing Trade. In: Mauro, F., McKibbin, W. and Dees, S., Eds., Globalization, Regionalism and Economic Interdependence, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 328-249.

- Feenstra, R.C. and Hanson, G.H. (1996) Globalization, Outsourcing and Wage Inequality. American Economic Review, 86, 240-245.

- Feenstra, R.C. and Hanson, G.H. (1999) Productivity Measurement and the Impact of Trade and Technology on Wages: Estimates for the U.S., 1972-1990. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114, 907-940. http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/003355399556179

- Slaughter, M.J. (2000) Production Transfer within Multinational Enterprises and American Wages. Journal of International Economics, 50, 449-472. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(98)00081-6

- Feenstra, R.C. and Hanson, G.H. (2001) Intermediaries in Entrepôt Trade: Hong Kong Re-Exports of Chinese Goods. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 8088.

- Amador, J. and Cabral, S. (2009) Vertical Specialization across the World: A Relative Measure. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 20, 267-280. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.najef.2009.05.003

- Nordås, H.K. (2008) The Impact of Services Trade Liberalisation on Trade in Non-Agricultural Products. OECD Trade Policy Working Papers, 81.

- Brülhart, M. (2009) An Account of Global Intra-Industry Trade, 1962-2006. The World Economy, 32, 401-459. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2009.01164.x

- Kumakura, M. (2009) Trade, Production and International Business Cycle Comovement. International Journal of Applied Economics, 6, 11-40.

- Bergstrand, J. and Egger, P. (2010) A General Equilibrium Theory for Estimating Gravity Equations of Bilateral FDI, Final Goods Trade and Intermediate Goods Trade. In: Brakman, S. and Van Bergeijk, P., Eds., The Gravity Model in International Trade: Advances and Applications, Cambridge University Press, New York, 29-70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511762109.002

- Yin, X.M. (2011) Chinas Intermediate Goods Trade with ASEAN: A Profile of Four Countries in Intermediate Goods Trade in East Asia: Economic Deepening through FTAs/EPAs. In: Kagami, M., Ed., BRC Research Report, 5, Bangkok Research Center, IDE-JETRO, Bangkok, Thailand.

- Greenaway, D., Hine, R. and Milner, C. (1994) Country-Specific Factors and the Pattern of Horizontal and Vertical Intra-Industry Trade in the UK. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv/Review of World Economics, 130, 77-100.

- Greenaway, D., Hine, R. and Milner, C. (1995) Vertical and Horizontal Intra-Industry Trade: A Cross Industry Analysis for the United Kingdom. The Economic Journal, 105, 1505-1518. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2235113

- Greenaway, D., Milner, C. and Elliott, R. (1999) UK Intra-Industry Trade with the EU North and South. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 61, 365-384. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1468-0084.00134

- Rodas-Martini, P. (1998) Intra-Industry Trade and Revealed Comparative Advantage in the Central American Common Market. World Development, 26, 337-344. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(97)10044-4

- Crespo, N. and Fontoura, M.P. (2004) Intra-Industry Trade by Types: What Can We Learn from Portuguese Data? Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv/Review of World Economics, 140, 52-79. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02659710

- Reganati, F. and Pittiglio, R. (2005) Vertical Intra-Industry Trade: Patterns and Determinants in the Italian Case. Journal of Current Research in Global Business, 11, 29-35.

- Leitão, N.C., Faustino, H. and Yoshida, Y. (2010) Fragmentation, Vertical Intra-industry Trade, and Automobile Com- ponents. Economics Bulletin, 30, 1006-1015.

- Abd-el-Rahman, K. (1991) Firms Competitive and National Comparative Advantages as Joint Determinants of Trade Composition. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv/Review of World Economics, 127, 83-97.

- Fontagné, L. and Freudenberg, M. (1997) Intra-Industry Trade: Methodological Issues Reconsidered. CEPII Working Papers, 97-01.

- Balassa, B. (1986) Intra-Industry Specialization: A Cross-Country Analysis. European Economic Review, 30, 27-42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0014-2921(86)90030-9

- Krugman, P. and Venables, A.J. (1995) Globalization and the Inequality of Nations. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110, 857-880. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2946642

- Venables, A.J. (1996) Equilibrium Locations of Vertically Linked Industries. International Economic Review, 37, 341- 359. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2527327

- Judson, R. and Owen, A. (1996) Estimating Dynamic Panel Data Models: A Practical Guide for Macroeconomists. Federal Reserve Board.

- Jones, R.W. and Kierzkowski, H. (2005) International Fragmentation and the New Economic Geography. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 16, 1-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.najef.2004.11.005

- Grossman, G.M. and Helpman, E. (2002) Outsourcing in a Global Economy. NBER Working Papers 8728, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

- Balassa, B. and Bauwens, L. (1987) Intra-Industry Specialization in a Multi-Country and Multi-industry Framework. Economic Journal, 97, 923-939. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2233080

- Jones, R.W. (2001) Globalization and Fragmentation of Production. Seoul Journal of Economics, 14, 1-13.

- Hoechle, D. (2007) Robust Standard Errors for Panel Regressions with Cross-Sectional Dependence. The Stata Journal, 7, 281-312.

- Helpman, E. and Krugman, P. (1985) Market Structure and Foreign Trade: Increasing Returns, Imperfect Competition, and the International Economy. MIT Press, Cambridge.

Appendix

Table A1. Intermediate goods in trade statistics—basic classes of goods in SNA in the cate- gories of BEC.

Source: UN International Trade Statistics. http://unstats.un.org/unsd/tradekb/Knowledgebase/Intermediate-Goods-in-Trade-Statistics

Table A2. ISIC REV 2.

Table A3. Coefficient estimates for Equation (9) with country dummies.

Heteroscedasticity-robust t statistics are in parentheses.

Table A4. Coefficient estimates for Equation (9) with country dummies.

Heteroscedasticity-robust t statistics are in parentheses.

NOTES

1Miroudot et al. [9] noted that “The difference between intermediate and capital goods lies in the latter entering as a fixed asset in the production process. Like any primary factor (such as labour, land, or natural resources) capital is used but not used up in the production process. On the contrary, an intermediate good is used, often transformed, and incorporated in the final output.” (Miroudot et al., 2009: p. 7).

2Helleiner [39] highlights the importance of intra-firm trade carried out by large multinational industries. Morawetz [40] relates the fragmentation of production to a high figure of qualified labour at a lower cost, the reduction of transport costs, and access to communications.

3This aspect will be examined in greater depth in Section 3.

4The impossibility of considering all partner countries was due to the lack of data on explanatory variables that have three dimensions (country, sector, time).

5See for example Ng and Yeats [45] ; Athukorala [47] ; Kaminski and Ng [5] ; Kimura [4] ; Kimura et al. [23] ; Athukorala and Yamashita [49] . It should be noted that Yeats [3] made reference to the changes in the SITC system of trade classification, which greatly expanded the number of product groups identified as “parts” and “components”.

6See, for example, Campa and Goldberg [41] , Feenstra and Hanson [51] ; Slaugther [52] ; Feenstra and Hanson [53] ; Hummels et al. [2] ; Amador and Cabral [54] .

7Türkcan [28] ; Nordas [55] ; Brülhart [56] ; Kumakura [57] ; Miroudot et al. [9] ; Bergstrand and Egger [58] ; Yin [59] .

8See UN (2007).

9See Table A1 and Table A2 for a description of classifications in the Appendix.

10See Türkcan (2011) for more on this issue.

11Horizontal intra-industry trade arises when there is two-way trade in intermediate goods that are similar in terms of quality, costs, and capital/labor techniques, but which have different characteristics or technological specification (for instance, citing an example provided by Türkcan (2011), the exchange of small-sized radiators for large-sized radiators). Vertical intra-industry trade represents trade in similar products of different qualities, but they are no longer the same in terms of unit production costs and factor intensities.

12The empirical analyses by Greenaway et al. [60] and Fontagné and Freudenberg [68] suggested that the results are not particularly sensitive to the range chosen.

13where CG, FG, and IG stand for capital goods, final goods and intermediate goods, respectively.

14For example, let us suppose that sector j in Italy is small, whereas partner country k0 has a big sector j and partner country k1 has a small sector j. Following the intuition of Hummels et al. [2] , the extent of vertical input two-way trade will be greater between Italy and country k0 than between Italy and country k1, simply because k0 produces more inputs than k1.

15All monetary explanatory variables are measured in US dollars at constant 1995 prices.

16As highlighted in our sample, the explanatory variables have three dimensions (partner country—industry—time), so there may be two kinds of individual effects (industry-specific effects or country-specific effects). Tables 4-6 provide the results obtained by considering industry-specific effects to be constant over the years. However, considering the country-specific effects to be invariant over time does not change the results in terms of significance and sign of coefficients (see Tables A3 and Table A4 in the Appendix).