Modern Economy

Vol.5 No.1(2014), Article ID:41954,10 pages DOI:10.4236/me.2014.51002

Influence of Living with Parents on Marrieds’ Happiness

Department of International Business, Chung Yuan Christian University, Chung-Li, Chinese Taipei

Email: sychu@cycu.edu.tw

Received November 9, 2013; revised December 9, 2013; accepted December 16, 2013

ABSTRACT

To enrich literature, this paper investigates influence of living with parents on marrieds’ happiness. It is an important issue in Chinese filial piety culture but rarely discussed. Data are drawn from Taiwan Social Change Survey in year 1995, 1997, 2000, 2001, 2002 and 2005. Empirical findings from ordered probit models show various associations between living with own/spouse’s parents and happiness of married women/men. Living with mother-in-law degrades married women’s happiness but it promotes married men’s happiness. Living with own mother lowers down married daughter’s happiness but married men’s happiness increases when living with own parents. These results echo to theoretical backgrounds about altruism, demonstration effect, and good/bad relation between married children and parents.

Keywords:Happiness; Living with Parents; Married

1. Introduction

One goal of economics study is to examine the determinants of people’s well-being and then improve it. Wellbeing portrays a person’s satisfaction under complex experiences and emotions. It is generally measured by life satisfaction and happiness. The former involves comprehensive evaluation by reviewing a certain period, while the later involves sensitive emotional reaction. Empirical research of well-being in economics has been developed rapidly for possibility of well-being measurement. Following research development, this paper extends to investigate determinants of well-being specific in Chinese culture to enrich literature.

This paper employs happiness instead of life satisfaction to measure well-being. This avoids invalidity of life satisfaction. Reference [1] stated that well-being measurement by life satisfaction might be limited by reliability. This is because people’s evaluation of life satisfaction might be influenced by mood or event background at the time of interview. It means that respondents might have significant different evaluations of life satisfaction for subtle events. In addition, [2] also pointed out that evaluation of life satisfaction from reviewing might be easily distorted by memory and with various errors. The authors hence suggest that feeling at that time or in a short time, like happiness, is the most representative. Moreover, [3] indicates that happiness and subjective feelings are interchangeable. Accordingly, happiness provides a better wellbeing measurement and this paper adopts it.

Extant literature of happiness tends to consider age, gender, marriage, education, income, health, politics, religion, child, community, and work as influencing factors. Different from current literature on happiness, this paper further examines the impact of living with parents on marrieds’ happiness. The phenomenon of living with parents after marriage is popular in Chinese society but rarely appears in western society. Even in extant eastern studies, it is also seldom formally examined. In Chinese society, filial piety has long been the mainstream culture. It is the general norm that married children are expected to live with their parents to implement filial piety. It seems that living with parents will bring higher level of happiness for the married since they carry out the mainstream culture. However, some theoretical arguments support various effects of living with parents on the marrieds’ happiness. The theoretical arguments under consideration of this paper are about altruism, demonstration effect, and relationship between the parent-in-law and married children in-law. Accordingly, this paper empirically investigates the influence of living with parents on the marrieds’ happiness based on these theoretical backgrounds.

To enrich the research, this paper explores the influence of living with parents on happiness in two dimensions. The first one distinguishes living with own parent and living with parent-in-law. The second one divides respondents into married women and married men. In Chinese culture, the relationship between married people with their parents is still shaped by a traditional patriarchal culture, fatherhood norm, and gender-role stereotype. Hence, married women and married men suffer differently in Chinese culture. In addition, the married suffer in own parent’s family differently from in the family of parent-in-law. Therefore, this paper is concentrated on four impacts on happiness: 1) influence of living with parentin-law on married women’s happiness, 2) influence of living with parent-in-law on married men’s happiness, 3) influence of living with own parent on married daughters’ happiness, 4) influence of living with own parent on married sons’ happiness.

2. Living with Parents in-Law and Living with Own Parents

This section provides theoretical background to support various relation between living with spouse’s/own parents and happiness for married women/men. This paper discusses the influencing factor of happiness in Chinese society with filial piety, which has not been mentioned in the literature. After marriage, filial piety can be implemented by living with parents. We start with discussing the impact of living with spouse’s parents on happiness for the married. The impact may vary between married women and married men according to disputes between mother and daughter in-law as well as good relation between mother and son in-law. We then discuss the impact of living with own parents on marrieds’ happiness. Altruism and demonstration effect make the impact different between married daughters and married sons.

2.1. Living with Parents in-Law

Chinese family stresses human relations. In various affinities, the most common issue for married women is disputes between the mother and daughter in-law. This is because that mother and daughter in-law has no bear bonding base; however, the daughter in-law is expected to take care of the mother in-law. The disputes are hence expected to be the reason of lower happiness of married women when they live with mother in-law.

The following studies focus on the issue of disputes between the mother and daughter in-law. They support that, other things being equal, living with the mother in-law can degrade happiness of married women due to disputes between them. Reference [4] discussed subjective perception of an adult female patient with depression under interactive pressure between the mother and daughter in-law. Research results provide evidence that disputes between mother and daughter in-law caused depression. Reference [5] found that the key reason for disputes between mother and daughter in-law in Chinese family is whether they consider the other party as “own people”. The author generates interview data in 38 households with three generations in Northern Taiwan from 1997 to 1998. Research findings show that the mother in-law treats her own children as “own people” while treats the daughter in-law as “other people”. However, the daughter in-law shall be “own people” in her spouse’s family according to Chinese family structure. Similarly, the daughter in-law does not consider husband’s family as “own people”. These lead to bad relation between the mother and daughter in-law and increase unhappiness of married women while living with the mother in-law. In addition, [6] pointed out that married women as daughters are hard to cut down real love for own parents; while as daughters in-law are hard to shape real love for spouse’s parents as own parents in a short time. These bring unhappiness to married women when living with spouse’s parent.

In traditional Chinese society, the relation the female has with parent in-law is different from that the male has. Married women shall serve spouse’s parents while living and give them proper burial after death rather than their own parents. Then their “real love” for own parents formed since birth and before marriage in frequent contact in their own family is separated from “obligation” or “due love” for parents in-law. Hence, the relation between the mother and daughter in-law is under separation and it drives down the happiness of married women.

In contrast, living with parent in-law may not decrease happiness of married men. Married men are generally required to take care of their own parents more than their parent in-law. In addition, son in-law owns higher status in spouse’s family compared with daughter in-law in Chinese patriarchy society. Mother in-law generally respects her male son in-law. Therefore, the problems about disputes and own/other people aforementioned become less serious. The good relation may even enhance happiness of son in-law when he lives with parent in-law.

To sum up, living with spouse’s parents produces adverse effect on happiness between married women and men. Disputes between the mother and daughter in-law predict a negative association between living with mother in-law and married women’s happiness. Good relation predicts a positive relation between living with mother in-law and married men’s happiness.

2.2. Living with Own Parents

Happiness of married children will be degraded when upstream transfer to parents is larger than downstream transfer from parents. Upstream transfer includes time, financial supports, or mental efforts offered by married children to their parents. Downstream transfer is what offered by parents to married children [7]. Following the respective of altruism, firstly, and demonstration effect, secondly, we will inspect that the upstream transfer varies between married daughters and married sons. It can be then derived that, other things equal, the impact of living with parents on happiness varies between them.

Firstly, altruism provides good explanations for the more care and support to parents from daughters than from sons. This represents that married daughters provide more upstream transfer and accordingly decrease their happiness while living with own parents. Reference [8] presented gender differences in altruism. Their experiments found that female helped more people than male. Reference [9] further explored differences in offering care for elders between male and female. The authors stated that since daughters tend to help others, they do more in taking care of parents than sons. The authors employ the time serving parents as the dependent variable. Empirical result supported that strong altruism lead daughters to offer more time caring for parents than sons. In a nutshell, male and female have different attitude to altruism and parents can get more care and support from daughters due to their strong altruism. Moreover, altruism supports the idea that daughters can offer more upstream transfer than sons. Therefore, we can conclude that compared with married sons, lower happiness degree of married daughters is resulted from more upstream transfer led by strong altruism while living with own parents.

Secondly, demonstration effect indicates that daughters give more care to parents than sons. In a three-generation family, demonstration effect refers that parents’ care for grandparents aims to guide their children to support parents in the future. Based on it, [10] investigate parents’ activity of taking care of grandparents. They pointed out that since, generally, the wife is younger than her husband and the female could live longer than the male, the female can benefit more from demonstration effect. Female hence have the inducement to offer more care to elders as a demonstration to get similar care from children in her future longer life. The author offered formal evidence to predict that parents will increase financial or time transfer to grandparents when parents’ life expectancy increases. Based on a dynamic structure, [10] find that daughters invest more in family network. Reference [7] continued demonstration effect theory and made causality test empirically. Their empirical result indicated that daughter visited parents more frequently than son. Inferring from demonstration effect, whiling living with own parents, married daughters provide more care for the elders and hence offer more upstream transfer than sons. More upstream lowers down married daughters’ happiness.

To sum up, altruism and demonstration effect deduce that married daughters offer more upstream transfer than married sons when living with own parents. Other things equal, due to higher upstream transfer, happiness of married daughters will be degraded when they live together with own parents.

3. Empirical Model, Data Description and Variable

This section builds up an ordered probit model for empirical investigation and introduces the data and variables under consideration.

3.1. Empirical Model

This paper uses a categorical and ordered variable to measure well-being, which is named as happiness degree. In other words, happiness degree is an ordinal variable and larger values are assumed to correspond to higher degree of happiness. This paper accordingly builds up an ordered probit model to estimate the impact of living with parents on happiness degree.

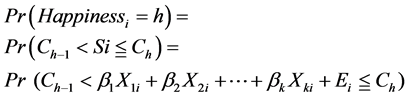

An ordered probit model sets the probability of observing happiness degree h of an individual i as the probability that the estimated linear function and a random error is within the range of the cut-points. It can be expressed by the below formulation.

(1)

(1)

where C is a set of cut-points, and an underlying score , Si, is estimated as a linear function of the independent variables, Xs, and a random error, E. The random error is assumed to be normally distributed. The coefficients, β1, β2, ... βk, together with the cut-points, C1, C2, ..., Ch−1 are estimated parameters. The subscript H in Ch−1 is the number of possible happiness degrees. C1 is taken as −∞, and Ch−1 is taken as +∞.

3.2. Data and Variable Explanation

Sociology studies on living with parents or disputes between the mother and daughter in-law are almost qualitative research and observe a very few respondents [4,5]. In view of this, this paper uses lots of data in quantitative analysis to compensate for literature shortage.

This paper collects data from Taiwan Social Change Survey (TSCS) of Academia Sinica entrusted by National Science Council. TSCS tracks the long-term trends of social changes and provides insight into them through national representative survey data on various topics. The data employed in our empirical work are gathered from the follows surveys: 1) the survey of family, interpersonal relations, mental state and leisure in the volume of 3-1 (II) in 1995, 2) the survey of social networks and communities in the volume of 3-3 (II) in 1997, 3) the survey of the communication behaviors, economic attitudes, political participation and globalization in the volume of 4-1 (I) in 2000, 4) the survey of social problems in the volume of 4-2 (II) in 2001, 5) the survey of social stratification in the volume of 4-2 (I) in 2002, 6) the survey of globalization, work, family, and mental health in the volume of 5-1 (I) in 2005.

3.2.1. Happiness Degree

The dependent variable of this paper is happiness degree. Questionnaire about happiness degree can be firstly found in 1995. Primal question on it in selected year is: overall speaking, are you happy in recently? The numbers of degree of happiness is different across years. However, it can be divided into four categories. The first category is unhappy = 0, tolerable happy = 1 and very happy = 2 in 1995 and 2000. The second category is very unhappy = 0, unhappy = 1, tolerable happy = 2, happy = 3 and very happy = 4 in 1997. The third category is very unhappy = 0, unhappy = 1, so-so = 2, tolerable happy = 3 and very happy = 4 in 2002. The fourth category is very unhappy = 0, unhappy = 1, tolerable happy = 2 and very happy = 3 in 2001 and 2005. In order to make various happiness categories comparable across years, we follow the rescaling method proposed by [11].

3.2.2. Variables of Living with Parents

This paper is concentrated on the influence of some rarely discussed variables about living with parents on happiness degree. Related question in the data is: “Whom are you living with: father, mother, father in-law, mother inlaw?” We set four dummy variables, namely living with father, living with mother, living with father in-law, living with mother in-law as 1, none as 0. They are separately denoted by MaL, PaL, MaO, and PaO for short. The questionnaires in 1995, 1997, 2000 and 2005 include whether you are living with spouse’s parents. The questionnaires in 1995, 1997, 2000, 2001, 2002 and 2005 include whether you are living with own parents. In addition, this paper further investigates whether the marginal effect of living with parents will be influenced by the respondent’s age. An interaction term between living with parents and age is hence added into the model. They are individually termed by MLa, PLa, MOa and POa for abbreviation.

This paper focuses on married. The influence of living on happiness varies with gender of married and living with own or spouse’s parent. Disputes between the mother and daughter in-law predict a negative relation between living with mother in-law and married women’s happiness. Adversely, good relation between the mother and son in-law predict a positive association between living with mother in-law and married men’s happiness. Altruism and demonstration effect suggests a positive impact of living with own parents on happiness for married sons and a negative one for married daughters.

Overall speaking, the years containing the question “living with parents” include 1995, 1997, 2000, 2001, 2002 and 2005. There are totally 10,606 respondents across these years. Married accounts for 78% including 5270 married women and 5336 married men. The rate of married women that are living with the mother in-law is about 12% to 17% across years and 15% is the mean. The average rate of married women living with the father in-law is about 11%. Both rates are not increasing or decreasing with time obviously. In addition, about 4% of married women are living with own mother and about 3% of married women are living with own father. In contrast, only 0.4% of married men are living with the mother in-law and 0.3% of married men are living with the father in-law. Furthermore, 23% of married men are living with own mother and about 16% of married men are living with own father.

Generally speaking, the rate of married living with husband’s parents is much higher than that with wife’s parents. It is a general phenomenon in Chinese patriarchy society. In addition, average rate of married living with male elders is lower than that with female elders. One possible reason is that male elders live shorter than female elders averagely.

3.2.3. Control Variables

Control variables in this paper include age, education level and relative income. Both age and the squared term of age are taken into account since literature suggests a potential non-linear relation between age and happiness [12]. They are denoted as Age and Age2.

Six dummy variables are employed to capture education levels namely primary school, junior high school, senior high school, other professional school, college and graduate school. They are individually termed by Prim, JunH, SenH, ProS, Coll, and Grad for short. No schooling is the base. Literature supports that more education enriches life condition and hence rises happiness degree [13].

As to income measurement, many studies support that relative income rather than absolute income affects happiness [13,14]. Therefore, we utilize family income survey data from Bureau of Executive Office in Taiwan to obtain average disposable income corresponding g to the respondent’s gender and age as the reference income. The difference between the respondent’s disposable income and its reference income is the relative income. Literature suggests a positive correlation between relative income and happiness. A respondent’s relative income is denoted as RelI for abbreviation.

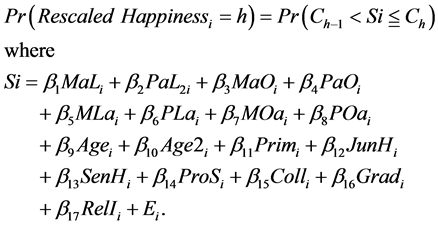

In a nutshell, Equation (1) can be rewritten in a detailed form implemented by our empirical work as below.

(2)

(2)

The first four variables are dummy variables capturing whether living with parents and MaL, PaL, MaO, and PaO individually represent living with mother in law, father in-law, own mother and own father. The value of one means “yes” while that of zero means “no”. The subsequent four variables are interaction terms of age and living with mother in law (MLa), father in-law (PLa), own mother (MOa) and own father (POa). Age represents the respondent’s age and its squared term is denoted as Age2. Education level is captured by six dummy variables including primary school (Prim), junior high school (JunH), senior high school (SenH), other professional school (ProS), college (Coll) and graduate school (Grad). No schooling is the base. RelI means the respondent’s relative income. All the rest notations are same with those in Equation (1).

4. Empirical Results

Table 1 lists empirical results from ordered probit model for married women while Table 2 for married men.

Sociology and psychology examine disputes between the mother and daughter in-law from the angle of “own people” and “other people”. They also investigate issues of taking care of parents from altruism or demonstration effect. All researches find that gender matters; the daughter in-law is different from the son in-law and married daughter is different from married son. It suggests us that we shall take gender of married into consideration when investigating the influence of living with parents on happiness. Hence, we divide samples into two gender groups separately listed in Tables 1 and 2.

In both Tables 1 and 2, different model specifications are set namely model A to model F. All models employ rescaled happiness degree as dependent variables. Due to the differences in the set of variables across years, each model collects data from different number of years and observations. Empirical results are explained in details in the next 3 subsections.

4.1. The Impact of Living with Parent in-Law

Firstly, we look at the impact of living with parent in-law on rescaled happiness degree for married women in Table 1 and for married men in Table2

Empirical results in Table 1 reveal a negative relation between living with mother in-law and married women’s happiness. This negative relation is robust across various model specifications through model A, C, D and F. In model D and model F, this coefficient is significantly negative at a 1% significance level. This finding tends to provide evidence supporting that disputes between the mother and daughter in-law caused married women’s unhappiness when living with mother in-law.

A critical factor affecting the relationship between mother and daughter in-law is whether or not they take each other into their inner circle [5]. In the Chinese patriarchy structure, mothers and daughters in-law tend to treat one another as outsiders; that is “other people”. The relationship between mothers and daughters in-law is not as close as mothers and their own daughters. Some mothers and daughters in-law cannot avoid conflict. This produces distant relationships and disputes between them are getting more serious when they are living together. In addition, married women in patriarchy culture usually suffer difficulty to endure but have to be bound the fatalistic life. They are compelling themselves the tight spot with daughter in-law role [4]. After entering a paternalistic-oriented dominant married life, married women generally face conflict with the male-centered beliefs of filial piety. Married women under their sway have no way to escape, and so may fall into a psychosomatic disorder. In a nutshell, cultural factors in the Chinese patriarchy structure lead to disputes between mother and daughter in-law and hence living with mother in-law decreases married women’s happiness degree.

In model D and F in Table 1, the coefficients of the interaction term between living with the mother in-law and age is significantly positive. It shows that disputes between the mother and daughter in-law make married women unhappier while living with the mother in-law. But, the negative effect on happiness is decreasing with married women’s age. It may show that older married women are more likely to adapt themselves to traditional Chinese culture and hence decrease imputes with mother in-law. Accordingly, the marginal effect of living with mother in-law on unhappiness degree decreases gradually with age of married women.

Moreover, it is interesting that married women become happier while living with their father in-law. This po

Table 1. Determinants of married women’s happiness.

“a” p < 0.001; “b” p < 0.01; “c” p < 0.05. Standard errors are given in parentheses.

sitive relation is robust across model A, C, D and F and it is significant at a 1% significance level in model A and C. This may because the Chinese fatherhood norm has been rooted in Chinese women’s mind, no matter how old she is, and hence disputes between mother and daughter inlaw disappear between father and daughter in-law. This can also explain that there is no significant effect of the interaction term between living with the father in-law and age on married women’s happiness. In addition, comparing the results of women’s unhappiness with mother in-law and their happiness with father in-law, it seems to remind that a woman should not give a hard time to another woman.

Table 2 reveals empirical results for married men just opposite to those for married women. A positive relation exists between living with mother in-law and married

“a” p < 0.001; “b” p < 0.01; “c” p < 0.05. Standard errors are given in parentheses.

men’s happiness. This positive relation shows in model A, C, D, and F and it is significant at a 10% significance level in model C, D and F. There is a Chinese saying that the mother in-law watched the son in-law with growing fascination. Moreover, Chinese patriarchy culture offers high status for married men in the spouse’s family. Therefore married men become happier while living with the mother in-law in such a pleasant relation. In addition, the marginal effect of living with mother in-law on mar ried men’s happiness does not change with their age based on insignificant coefficient of the interaction term between living with mother in-law and age.

4.2. The Impact of Living with Own Parents

Altruism and demonstration effect provide theoretical background to explain the effect of living with own parents on marrieds’ happiness and its discrepancy between married daughters and men. Corresponding to these theoretical backgrounds, our empirical data show that, in our sample of 5569 married, 97% of them have children and 47% are living with elders. We have 2656 married samples living with parents. Among them, 94% are from three-generation family. Accordingly, demonstration effect can be implemented hereinto.

As for the relation between living with own parents and happiness degree, both positive and negative association could occur. This is because carrying out the mainstream culture of filial piety drives marrieds’ happiness up; however, altruism and demonstration effects may lower down their happiness, especially for married women. Accordingly, the direction of the influence of living with own parents on happiness depends on the aggregated influence of these impacts.

Models B, C, E and F in Table 1 show both positive and negative association between living with own parents and happiness for married daughters since two kinds of factors function simultaneously as abovementioned. Carrying out filial piety increases their happiness but altruism and demonstration effects make their happiness down. However, only the coefficients of living with own mother in model B and C are significant and they are significantly negative at a 1% and 5% significance level. Therefore, empirical evidence supports that altruism and demonstration effects dominate among married women.

In contrast, Table 2 only shows only a positive relation between living with own parents and married sons’ happiness degree. Model B and C show significantly positive coefficients of living with own mother at a 10% significance level and model E and F show significantly positive coefficients of living with own father at a 10% and 5% significance level. This indicates that carrying out filial piety, altruism and demonstration effects aggregately rises married sons’ happiness when they live with their own parents.

As aforementioned, happiness of married will be degraded when upstream transfer is larger than downstream transfer. Literature supports the idea that married daughter can offer more upstream transfer than married son while living with own parents either because daughters have stronger altruism or because daughters have longer life expectancy and hence show stronger demonstration effect. Married women give more mental efforts or time while living with own parents, so their upstream transfer is more. Other things being equal, more upstream transfer leaves fewer resources for married daughters. It therefore leads to lower happiness degree of married daughter when living with own parents evident in Table1 In contrast, married men get weaker altruism and demonstration effect. That means they give less upstream transfer to parents when living with them. The positive influence on married son’s happiness of implementing filial piety outweighs the negative one of upstream. Accordingly married son’s happiness degree could be increased while living with own parents evident in Table2

4.3. The Impact of Control Variables

The impact of control variables affecting happiness are discussed in this section. We introduce empirical results one by one factor for both married women and married men. According to Table 1 for married women, age influences happiness degree in a nonlinear fashion. The happiness degree increases with age but with a decreasing increase with age. However, age tends to be not a determinant of happiness for married men in Table2 Reference [12] provides more detailed discussion about the relationship between happiness and age.

Both Tables 1 and 2 show that education level has a positive correlation with happiness degree for both married women and married men with education level lower than university. This result is consistent with that of literature [13,14] which indicates that education can promote happiness. However, the impact of education level on happiness turns to be negative when schooling reaches university level for married men. More research is necessary for further disentangle the result.

Moreover, both Tables 1 and 2 reveal that higher relative income decreased the probability of the unhappiest and increases the probability of the happiest. It corresponds to the literatures such as [15,16]. But the coefficient of relative income is really small, which is consistent with [17]’s statement that previous literatures overestimated income influence on well-being.

In addition to age, education and relative income, this paper also investigates other determinants such as religion, child, community, work, regions and politics attitude. However, no significant impact of them is shown. In addition, we also modify the data into annual analysis and find that the impacts on happiness of all the determinants under consideration are robust. These empirical results are available upon request by readers.

5. Conclusions

In Chinese filial piety culture, living with parents after marriage is expected and it is a popular phenomenon. This rarely occurs in western world, even in eastern society, and there is few literature examining influence of living with parents on marrieds’ happiness. In order to enrich literature, this paper disentangles associations between living with own/spouse’s parents and happiness of married women/men. More than 3000 observations are drawn from Taiwan Social Change Survey in year 1995, 1997, 2000, 2001, 2002 and 2005.

Theoretical backgrounds in sociology indicate that, in Chinese culture, the relationship between married people with their parents is still shaped by a traditional patriarchal culture, fatherhood norm, and gender-role stereotype. We empirically test the theoretical arguments of disputes/ concordance between married children and parents, altruism and demonstration effects. Empirical evidence from ordered probit models supports these arguments. Living with mother-in-law degrades married women’s happiness but it promotes married men’s happiness. The former is arisen by disputes between mother and daughter-in-law rooted in Chinese family while the latter is led by good relation between mother and son-in-law under fatherhood norm. In addition, living with own mother lowers down married daughter’s happiness but married men’s happiness increases with living with own parents. This is because, in contrast with married sons, married daughters possess stronger altruism and demonstration effect and hence provide more upstream to parents and degrade their happiness when living with own parents.

This paper confirms that the effect of living with own/ spouse’s parents on happiness varies between married women and men. It enriches the study of the impact of living with parents in Chinese filial piety culture.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the financial support by Grant NSC100-2410-H-033-020 from the National Science Council, Taiwan.

REFERENCES

- R. Lucas, E. Diener and E. M. Suh, “Discriminant Validity of Well-Being Measures,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 71, 1996, pp. 616-628. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.3.616

- D. Kahneman and A. B. Krueger, “Developments in the Measurement of Subjective Well-Being,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 20, 2006, pp. 3-24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/089533006776526030

- L. Lu, “Who Is Happy in Taiwan? The Demographic Classifications of the Happy Person,” Psychologia, Vol. 53, 2010, pp. 55-67. http://dx.doi.org/10.2117/psysoc.2010.55

- Y. H. Huang, S. H. Yu and M. F. Lin, “A Depressed Woman’s Views of Disease Experiences and the Relation of Mother and Daughter-in-law,” Formosa Journal of Mental Health, Vol. 22, No. 1, 2009, pp. 27-50.

- H. M. Kung, “Who Is One of Our Own? The In-Group/ Out-Group Effect on the Relationship between Motherand Daughter-in-law,” Indigenous Psychological Research in Chinese Societies, Vol. 16, 2001, pp. 43-87.

- Y. Y. Yang, “Zijiren: The Relationship between Motherand Daughter-in-law as Seen from a Classificatory Scheme of Chinese Interpersonal Affection,” Indigenous Psychological Research in Chinese Societies, Vol. 16, 2001, pp 3-41.

- A. Mitrut and F. C. Wolff, “A Causal Test of the Demonstration Effect Theory,” Economics Letters, Vol. 103, 2009, pp. 52-54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2009.01.029

- J. Andreoni and L. Vesterlund, “Which Is the Fair Sex? Gender Differences in Altruism,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 116, 2001, pp. 293-312. http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/003355301556419

- M. Jellal and F. C. Wolff, “Cultural Evolutionary Altruism: Theory and Evidence,” European Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 18, 2002, pp. 241-262. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0176-2680(02)00079-4

- M. Jellal and F. C. Wolff, “Shaping Intergenerational Relationships: The Demonstration Effect,” Economics Letters, Vol. 68, 2000, pp. 255-261. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0165-1765(00)00247-0

- H. E. Lim, “The Use of Different Happiness Rating Scales: Bias and Comparison Problem,” Social Indicators Research, Vol. 87, 2008, pp. 259-267. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9171-x

- P. Frijtersa and T. Beattonb, “The Mystery of the UShaped Relationship between Happiness and Age,” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, Vol. 82, No. 2-3, 2012, pp. 525-542. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2012.03.008

- W. C. Chen, “How Education Enhances Happiness: Comparison of Mediating Factors in Four East Asian Countries,” Social Indicators Research, Vol. 106, 2012, pp. 117- 131. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9798-5

- M. W. Tsou and J. T. Liu, “Happiness and Domain Satisfaction in Taiwan,” Journal of Happiness Studies, Vol. 2, No. 3, 2001, pp. 269-288. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1011816429264

- A. E. Clark and A. J. Oswald, “Satisfaction and Comparison Income,” Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 70, No. 1, 1996, pp. 359-381. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0047-2727(95)01564-7

- A. Deaton, “Income, Health and Wellbeing around the World: Evidence from the Gallup World Poll,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 22, No. 2, 2008, pp. 53-72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/jep.22.2.53

- D. Kahneman, A. B. Krueger, D. Schkade, N. Schwarz and A. A. Stone, “Would You Be Happier If You Were Richer? A Focusing Illusion,” Science, Vol. 312, 2006, pp. 1908-1910. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1129688

Appendix

The question is “Overall speaking, are you happy in recently?”

In 1995, respondent can choose among

□ unhappy □ tolerable happy □ very happy In 1997, respondent can choose among

□ very unhappy □ unhappy □ tolerable happy □ happy □ very happy In 2000, respondent can choose among

□ unhappy □ tolerable happy □ very happy In 2001, respondent can choose among

□ very unhappy □ unhappy □ tolerable happy □ very happy In 2002, respondent can choose among

□ very unhappy □ unhappy □ so-so □ tolerable happy □ very happy In 2005, respondent can choose among

□ very unhappy □ unhappy □ tolerable happy □ very happy