Psychology

Vol.5 No.6(2014), Article ID:45257,9 pages DOI:10.4236/psych.2014.56059

Association between Perceived Social Support and Subjective Well-Being among Japanese, Chinese, and Korean College Students

Terumi Matsuda1, Akira Tsuda2, Euiyeon Kim3, Ke Deng4

1Graduate School of Psychology, Kurume University, Kurume, Japan

2Department of Psychology, Kurume University, Kurume, Japan

3Department of Education, Inha University, Inchon, Korea

4Institute of Comparative Studies of International Cultures and Societies, Kurume University, Kurume, Japan

Email: matsuda88@std.mii.kurume-u.ac.jp

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 11 January 2014; revised 13 February 2014; accepted 15 March 2014

ABSTRACT

Subjective well-being (SWB) consists of life satisfaction, the presence of positive affect (PA), and the absence of negative affect (NA). This study examines the associations between perceived social support and SWB among Japanese, Chinese, and Korean college students. We hypothesized that perceived social support will be associated with life satisfaction directly and indirectly through PA and NA among the three groups. A total of 1332 (466 Japanese, 449 Chinese, 417 Korean) college students completed surveys measuring life satisfaction, PA, NA, and perceived social support from family, friends, and a significant other. Results of the path analysis showed that family support reduced NA and significant others support improved PA, and that both of types of support were associated with life satisfaction among the three groups. It was suggested that perceived social support contributes to improve SWB among Japanese, Chinese, and Korean college students.

Keywords

Perceived Social Support, Subjective Well-Being, Japan, China, Korea, College Students

1. Introduction

Positive psychology (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000) analyzes subjective well-being (SWB), or the way in which people make cognitive and affective evaluations of their lives. SWB is an inclusive term used to refer to life satisfaction, the presence of positive affect (PA), and the absence of negative affect (NA) (Diener, Suh, Lucas, & Smith, 1999). Life satisfaction is the cognitive component of evaluation (Diener, Oishi, & Lucas, 2003). PA and NA are the emotional components of evaluation. High levels of PA indicate the experience of many pleasant emotions and moods, whereas low levels of NA indicate the experience of few unpleasant emotions and moods (Diener, 2000).

PA is a key predictor of life satisfaction (Lightsey, 2011). PA has a well-known relationship with life satisfaction, with correlations often around .50 (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985). The particular pathways by which PA predicts and may affect life satisfaction, however, are not well understood (Lightsey, 2011). Wirtz, Chiu, Diener and Oishi (2009) suggested that Asian students display less intense PA and more intense NA than European Americans when judging their life satisfaction.

Ryff and Keyes (1995) have identified positive relations with others as one of several key eudaimonia dimensions of well-being. Social support is defined as the provision of psychological and material resources of a social network intended to enhance the ability of an individual to cope with stress. The social support we receive from others are identified as predictors of health and well-being (Cohen, Underwood, & Gottlieb, 2000). It was reported that Asians are less likely to use social support to help cope with stress than European Americans; however, Asians perceived emotional support as having a positive effect on well-being and health (Uchida, Kitayama, Mesquita, Reyes, & Morling, 2008). Asians depend on the presence of harmony in their interpersonal relationships (Wirtz et al., 2009).

Perceived social support has received significant attention in the search for predictive values in SWB. Several decades of social science research have provided evidence of the positive effects of perceived social support on emotional and physical functioning (Cohen et al., 2000). The perception of social support available is more important than the actual amount of social support provided. Perceived social support refers to the beliefs people hold regarding the level and quality of support that is available to them. It is thought that perception of social support is a most salient factor precisely because it shows how an individual thinks about the support available to them, and whether it can be called upon when needed (Gallagher & Vella-Brodrick, 2008).

Social support has been differentiated according to partner, family, and friends (Walen & Lachman, 2000). Social supports from family and friends are both positively associated with life satisfaction, but the interaction between the two variables was not statistically significant (Sheets & Mohr, 2009). Social support from family and other sources is associated with PA in adolescence (Lyubomirsky, Tkach, & DiMatteo, 2006); however, it is unclear whether social support is associated with PA and NA among Japanese, Chinese, and Korean students.

Diener et al. (1999) suggested that theories must be refined to make specific predictions about how input variables differentially influence the components of SWB. It is now clear that there are separable components of SWB that exhibit unique patterns of relations with different variables (Diener et al., 1999).

We hypothesized that perceived social support will be associated with life satisfaction directly and indirectly through PA and NA among the three groups. Social support should directly lead to a positive state, and this positive state should be related to increased levels of well-being (Greenglass & Fiksenbaum, 2009). Perceived social support is negatively associated with NA and positively associated with PA; these factors are capable of directly or indirectly predicting life satisfaction (Figure 1).

This study examines the association between perceived social support and SWB. The relationship between perceived social support and SWB is predicted to be strong, as well as positive among East Asians; moreover, it is predicted that similar patterns will be found among the three groups. It is important to determine whether these predicted patterns can be extended to the three East Asian countries in the study (Uchida et al., 2008).

In this paper, Japan, China, and Korea were selected because these countries are geographically proximate and have had historically stronger influences on each other than other East Asian countries (Park, Lee, Shin, Liu, Shang, Yamashita, & Lim, 2012). By comparing Japanese, Chinese, and Korean college students, their commonalities as well as differences can be determined in the role of social support, and its direct or indirect association with life satisfaction through PA and NA.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants were recruited from universities in Japan, China, and Korea. A total of 1332 students completed the

Figure 1. Hypothesized model relating perceived social support and SWB.

questionnaire, including 466 Japanese (232 males, 234 females; average age 19.8 years), 449 Chinese (183 males, 266 females; average age 20.2 years), and 417 Korean (197 males, 220 females; average age 22.6 years) students who agreed to participate in this study.

The questionnaire, which was developed in Japanese, Chinese, and Korean languages elicited demographic information, including age, sex, educational status, and questions about SWB (life satisfaction, PA, and NA), and perceived social support.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Life Satisfaction

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) (Diener et al., 1985; Sumino, 1994; Kim, 2007) is a 5-item scale that assesses the cognitive component of WSB. Participants indicate, for example, how satisfied they are with their lives and how close their life is to their ideal life. Questions are answered on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree), and responses are summed to provide an overall score. The possible range of scores on the questionnaire ranges from 5 (low satisfaction) to 35 (high satisfaction). The two-month test-retest correlation coefficient was .82, and the coefficient alpha was .87 (Diener et al., 1985). In this study, coefficient alphas were .84, .76, .86, for Japanese, Chinese, and Korean students, respectively.

2.2.2. The Positive and Negative Affect

The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988; Kawahito, Otsuka, Kaida, & Nakata, 2011; Huang, Yang, & Ji, 2003; Lee, Kim, & Lee, 2003) consists of 20 self-report items, 10 of which measure PA (e.g., determined, inspired, enthusiastic, active) and 10 of which measure NA (e.g., jittery, afraid, nervous, ashamed). Participants are asked to indicate on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all; 5 = extremely) the extent to which they experienced each emotion or feeling during the past month. Items were summed to create a score for each participant with a maximum score of 50 and a minimum score of 10. The coefficient alpha was .87, and the 8-week test-retest reliability was .58 for the PA scale. The correlation between the NA and PA scales was invariably low, ranging from −.12 to −.23 (Watson et al., 1988). The PANAS is widely used, and extensive support exists for the reliability and validity of PANAS scores among college students, and other populations. In this study, the coefficient alpha was .85, .88, .79, for Japanese, Chinese, and Korean students, respectively.

2.2.3. Perceived Social Support

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) (Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, 1988; Iwasa et al., 2007) was designed to measure perceptions of social support quality. The MSPSS has good internal and test-retest reliability, as well as moderate construct validity. This 12-item scale has a 7-point response format (1 = very strongly disagree; 7 = very strongly agree). It comprises three 4-item subscales, which assess the level of support from family, friends, and a significant other. Items were summed to create a subscale score for each participant with a maximum score of 28 and a minimum score of 4. A higher score in each of these scales indicates a higher quality of perceived social support.

Examples of items related to family support include “My family really tries to help me” and “I get the emotional help and support I need from my family.” Examples of items related to support from friends include “My friends really try to help me” and “I have friends with whom I can share my joys and sorrows.” Example of items related to a significant other include “There is a special person who is around when I am in need” and “I have a special person who is a real source of comfort for me.” The question regarding a significant other refers to a special person, which was not defined as a specific relationship so as to allow the respondent to interpret this person as someone relevant to him or her, such as a romantic partner, a close friend, teacher, or some other important person in one’s life (Canty-Mitchell & Zimet, 2000).

2.3. Procedures

Participants were assured that the data would only be used for research purposes and that participation was voluntary. Approval of this study was obtained from an ethics committee at Kurume University. The paper-pencil survey was conducted from November 2012 to January 2013.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

First, descriptive statistics were used for demographics, perceived social support (family, friends, and a significant other), life satisfaction, PA, and NA. The differences in mean values were examined using one-way ANOVA with the three groups as an independent variable. Eta2 values of .01, .06, and .14 were interpreted as small, medium, and large, respectively (Cohen, 1988). Correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the relationship between life satisfaction, PA, NA, family support, friends support, and a significant other’s support. The path analysis was used to examine how perceived social support related to SWB. A hypothesized model was tested in the three groups. To evaluate overall model fit, several fit indices were used. Data was analyzed using SPSS 18.0.

3. Results

The means and standard deviations among variables are presented in Table 1 for each group.

The ANOVA revealed a significant effect. The results of Tukey’s HSD test suggest that life satisfaction and PA scores were significantly higher among Korean students than among Japanese and Chinese students, F (21,329) = 26.67, p < .001, η2 = .04; F (21,329) = 15.14, p < .001, η2 = .02. The NA score in Japanese students was the highest among the three groups, F (21,329) = 85.99, p < .001, η2 = .11. The family support score was the highest among Chinese students, F (21,329) = 43.09, p < .001, η2 = .06. Significant others support score was the highest among Korean students, F (21,329) = 44.42, p < .001, η2 = .07.

Table 2 shows the correlation coefficients among the six variables. Significant correlations were found

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and multiple comparisons among three groups.

Note: SWLS = Life satisfaction, PA = Positive Affect, NA = Negative Affect, J = Japan, C = China, K = Korea.

Table 2. Correlations of variables among Japanese, Chinese, and Korean college students.

Note: *p < .05, **p < .01.

among the six variables except family support and PA among Chinese students. The life satisfaction positively correlated with PA and negatively with NA. There was a positive correlation between NA and PA among Japanese and Chinese students, however, there was a negative correlation among Korean students.

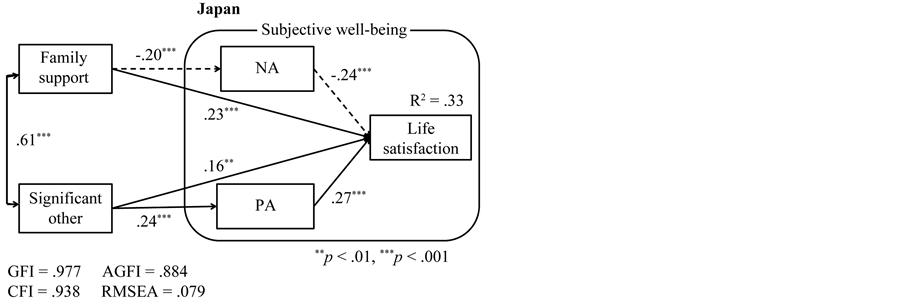

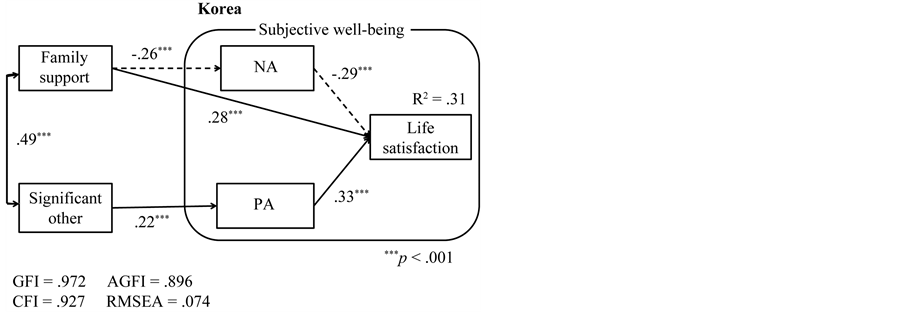

Path analysis was used to examine how social support is associated with PA, NA, and life satisfaction. A hypothesized model was tested among the three groups. It was indicated that family support reduced NA and significant others support improved PA, and that both of them were associated with life satisfaction among Japanese students (Figure 2). Friends support was not associated with NA, PA, or life satisfaction.

A similar association was found among Chinese students (Figure 3); however, family support was not directly associated with life satisfaction among Chinese students. Korean students showed similar associations to those of Japanese and Chinese students (Figure 4); however, significant others support was not directly associated with life satisfaction among Korean students.

To evaluate the overall model fit, several fit indices were used: the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), the adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). According to Tasaki (2008), a model is considered to have very good fit if the GFI, AGFI, and CFI are greater than .90, and the RMSEA is below .08. Therefore, the three models provided an acceptable fit.

Figure 2. The model relating perceived social support and SWB among Japanese college students.

Figure 3. The model relating perceived social support and SWB among Chinese college students.

Figure 4. The model relating perceived social support and SWB among Korean college students.

4. Discussion

This study examined the association between perceived social support and SWB among Japanese, Chinese, and Korean students. The results of this study indicated that there are commonalities as well as differences among the three groups.

Life satisfaction and PA scores among Korean students were higher than among Japanese or Chinese students. NA score among Japanese students was the highest among the three groups. The family support score was the highest among Chinese students. A significant other’s support score was the highest among Korean students. The effect size was small to medium, however, it was suggested that the level and contents of SWB, and perceived social support had different characteristics among the three groups.

This study aimed to establish an association between perceived social support and SWB among the three groups. We evaluated the model fitness using GFI, AGFI, CFI, and RMSEA. The three models showed acceptable fitness with a higher GFI (>0.9), a higher AGFI (>0.8), a higher CFI (>0.9), and a lower RMSEA (<0.1) (Byrne, 2001).

It was revealed that perceived social support is associated with life satisfaction directly and indirectly, through PA and NA among the three groups. Perceived social support is associated with SWB as was found in previous work (Walen & Lachman, 2000). Perceived social support has differentially influence the components of SWB. It was clarified that there are separable components of SWB that exhibit unique patterns of relations with perceived social support.

In this study, it was revealed that there were common associations among the three groups. Family and significant others support were associated with SWB among the three groups directly or indirectly. It was found that family support reduced NA and increased life satisfaction, whereas significant others support was associated with PA and increased life satisfaction. Perceived family support plays an important role in reducing depression (Greenglass & Fiksenbaum, 2009). In this study, it was confirmed that family support reduces NA. It was suggested that a supportive family relationship is associated with life satisfaction, and reduces NA and its manifestations such as depression. Significant other’s support is associated with life satisfaction and increases PA. Fukuoka (2012) mentioned that a close friend’s support is related to PA among college students.

Sheets & Mohr (2009) suggested that friend’s support among college students is important, as it is a period for shifting from family to peer support. Sheets & Mohr (2009) revealed that a family member or a close friend can be important or influential in one’s life. However, friends support was not associated with PA, NA, or life satisfaction directly or indirectly among any of the three groups. Fukuoka (2012) mentioned the differences between general friends and a close friend. In this study, a close friend may be considered to be a significant other. We should further clarify who may count as a significant other for college students in further studies.

There were several differences among the three groups. Family support was directly associated with life satisfaction among Japanese and Korean students. Family support influences both affective and cognitive evaluation of SWB among Japanese and Korean students, whereas cognitive evaluation of Chinese students did not have any direct affect. Pethtel and Chen (2010) showed that perceived family’s life satisfaction was related to life satisfaction for Chinese. Further research is required about cognitive evaluation of SWB among Chinese students. A significant other’s support was directly associated with life satisfaction among Japanese and Chinese students, whereas Korean students did not have any direct affect.

These perceived social supports had direct effects on life satisfaction. Social support should lead directly to a positive state of one’s health. This positive state should consequently be related to increased levels of well-being (Greenglass & Fiksenbaum, 2009). Thus, support from family and a significant other are important to the SWB of students. We need to support college students by encouraging them to build good relationships with their families and close friends to increase their SWB.

The present results have made the following contributions to literature. This study is one of the first to show that the common factors as well as the differences in perceived social support and its direct or indirect associations with life satisfaction through PA and NA among three East Asian countries. This study represents a contribution within the field of positive psychology be demonstrating how perceived social support was associated with PA, NA, and life satisfaction.

Limitations and Future Discussions

There are several limitations to this study. First, we recruited college students from limited areas. The results cannot be generalized to the entire population of Japanese, Chinese, and Korean college students. Second, there was no association between friends support and SWB. We should further clarify the differences between general friends and a close friend when we ask the perceived friends support. Third, the findings are based on crosssectional comparisons of individuals among three groups. Use of a cross-sectional design makes it impossible to make inferences regarding the direction of influence. We believed that perceived social support from family and a significant other would contribute to SWB. However, it is possible that what we viewed as life satisfaction, PA, and NA influenced perception of social support. In future studies, a longitudinal study would enable us to explore the result of this study to enhance the association between the perceived social support and SWB.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (22330196) to A. T.

References

- Byrne, B. E. (2001). Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Canty-Mitchell, J., & Zimet, G. D. (2000). Psychometric Properties of Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support in Urban Adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 28, 391-400. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1005109522457

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Science (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Cohen, S., Underwood, L., & Gottlieb, B. (2000). Social Support Measurement and Intervention: A Guide for Health and Social Scientists. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Diener, E. (2000). Subjective Well-Being. The Science of Happiness and a Proposal for a National Index. American Psychologist, 55, 34-43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71-75. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

- Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. E. (2003). Personality, Culture, and Subjective Well-Being: Emotional and Cognitive Evaluations of Life. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 403-425. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145056

- Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective Well-Being: Three Decades of Progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276-302. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276

- Fukuoka, Y. (2012). Positive and Negative Interactions That Accompany Everyday Stress and Psychological Well-Being: An Examination of the Influence of the Interactions with a Close Friend in the Last Month. Kawasaki Medical Welfare Journal, 22, 53-59.

- Gallagher, E. N., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2008). Social Support and Emotional Intelligence as Predictors of Subjective Well-Being. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 1551-1561. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.01.011

- Greenglass, E. R., & Fiksenbaum, L. (2009). Proactive Coping, Positive Affect, and Well-Being. European Psychologist, 14, 29-39. http://dx.doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040.14.1.29

- Huang, L., Yang, T. Z., & Ji, Z. M. (2003). Applicability of the Positive and Negative Affect Scale in Chinese. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 1, 54-56.

- Iwasa, H., Gondo, Y., Masui, Y., Masui, Y., Inagaki, H., Kawai, C., Otsuka, R., Ogawa, M., Takayama, M., Imuta, H., & Suzuki, T. (2007). Development of a Japanese Version of Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, and Examination of Its Validity and Reliability. Journal of health and welfare statistics, 54, 26-33.

- Kawahito, J., Otsuka, Y., Kaida, K., & Nakata, A. (2011). Reliability and Validity of the Japanese Version of 20-Item Positive and Negative Affect Schedule. Hiroshima Psychological Research, 11, 225-250.

- Kim, J. H. (2007). The Relationships between Life Satisfaction/Life Satisfaction Expectancy and Stress/Well-Being: An Application of Motivational States Theory. The Korean Journal of Health Psychology, 12, 325-345.

- Lee, H. H., Kim, E. J., & Lee, M. K. (2003). A Validation Study of Korea Positive and Negative Affect Schedule: The PANAS Scales. The Korean Journal of Clinical Psychology, 23, 935-946.

- Lightsey, O. R. (2011). Do Positive Thinking and Meaning Mediate the Positive Affect—Life Satisfaction Relationship? Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 43, 203-213. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0023150

- Lyubomirsky, S., Tkach, C., & DiMatteo, M. R. (2006). What Are the Differences between Happiness and Self-Esteem? Social Indicators Research, 78, 363-404. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-0213-y

- Park, H. L., Lee, H. S., Shin, B. C., Liu, J. P., Shang, Q., Yamashita, H., & Lim, B. (2012). Traditional Medicine in China, Korea, and Japan: A Brief Introduction and Comparison. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2012, Article ID: 429103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2012/429103

- Pethtel, O., & Chen, Y. (2010). Cross-Cultural Aging in Cognitive and Affective Components of Subjective Well-Being. Psychology and Aging, 25, 725-729. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0018511

- Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The Structure of Psychological Well-Being Revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 813-832.

- Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive Psychology: An Introduction. American Psychologist, 55, 5-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

- Sheets, R. L., & Mohr J. J. (2009). Perceived Social Support from Friends and Family and Psychosocial Functioning in Bisexual Young Adult College Students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56, 152-163. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.56.1.152

- Sumino, Z. (1994). Development of Japanese Version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS). Proceedings of the 51st Annual Meeting of Japanese Association of Educational Psychology, 36, 192.

- Tasaki, K. (2008). Cross-Cultural Research Methods in Social Sciences. Kyoto: Nakanishiya.

- Uchida, Y., Kitayama, S., Mesquita, B., Reyes, J. A. S., & Morling, B. (2008). Is Perceived Emotional Support Beneficial? Well-Being and Health in Independent and Interdependent Cultures. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 741- 754. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167208315157

- Walen, H. R., & Lachman, M. E. (2000). Social Support and Strain from Partner, Family, and Friends: Costs and Benefits for Men and Women in Adulthood. Journal of Social & Personal Relationships, 17, 5-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0265407500171001

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and Validation of Brief Measures of Positive and Negative Affect: The PANAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063-1070. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

- Wirtz, D., Chiu, C., Diener, E., & Oishi, S. (2009). What Constitutes a Good Life? Cultural Differences in the Role of Positive and Negative Affect in Subjective Well-Being. Journal of Personality, 77, 1167-1196. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00578.x

- Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52, 30-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2