Creative Education

Vol.08 No.02(2017), Article ID:73929,13 pages

10.4236/ce.2017.82016

An Emerging Model of E-Learning in Palestine: The Case of An-Najah National University

Saida Jaser Affouneh1*, Ahmed Amin Awad Raba2

1ELearning Centre, An-Najah National University, Nablus, Palestine

2College of Education and Teacher Training, An-Najah National University, Nablus, Palestine

Copyright © 2017 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: December 20, 2016; Accepted: February 3, 2017; Published: February 6, 2017

ABSTRACT

An-Najah National University (ANU), a Palestinian non-governmental public university located in Nablus in the northern part of Palestine, serves 17,807 students with 1020 professors in 11 faculties, and has been striving to integrate technology in its systems to keep up with the global flux of change in all aspects of life. For 10 years An-Najah has pursued the integration of e-learning in residential, blended and fully online delivery. Following a brief summary of the history of An-Najah National University, change management strategies are featured, highlighting specific successful techniques. The case study concludes a description of the change management model that emerged in addition to indicators of a great impact on students’ satisfaction and staff members’ participation ratios.

Keywords:

Blended Learning Model, Strategic Planning, Change Management, E-Learning, Synchronous

1. Introduction

ANU was established in 1977 and has emerged as the largest university in Palestine, as well as Palestine’s leader in higher education. ANU is a public university that is supervised by a Board of Trustees. The university has over 17,807 students and 1020 professors in 11 academic faculties. ANU offers both undergraduate and graduate degrees.

ANU aspires toward improving the quality of its graduates through enhancing technology in teaching and learning ( ANU, 2011 ). Over the last ten years, it moved toward excellence in teaching and learning, and improved its reputation not only in the Arab world but also among international higher education institutions with a clear vision that indicates dedication to promoting understanding, providing the highest quality undergraduate and graduate education, and serving as a leader in the scientific research. ANU acts as a base for sustainable development by encouraging students and the University community to assume leadership roles and to participate in serving the society (http://www.najah.edu/page/2674).

ANU has effectively participated in many e-learning projects, and its faculty members have designed pilot-blended courses, especially in the faculties of engineering, education, and information technology. In 2010 ANU published more than 120-recorded lectures as a prelude to its institutional staging of an e-learning strategy. In 2012, the e-Learning Center was established under the supervision of the vice president of Academic Affairs and the director of pedagogical affairs. Six technicians were employed for this purpose, and two instructional designers are currently working at the center on a part-time basis. A strategic committee for e-learning was formed whose main responsibility is to set rules and regulations for the center, and to follow up the university’s transition into e-learning. The committee usually meets twice per semester. The University Computer Center, responsible for the administration of the learning management system, also recognized the need for the e-Learning Center and supported the initiatives. From the aforesaid effort, it is noticed that the researchers aimed to document the university willingness to integrate technology in its systems for all the faculty members.

2. Statement of the Problem

One of the main barriers to any change management strategy is managing the human dimension of acceptance and resistance. A significant obstacle to the integration of technology into education at ANU was the faculty members’ resistance to considering new teaching techniques. Many faculty members preferred to use their old traditional methods of teaching. This may be due to either the faculty members’ lack of instructional technology skills, or to the lack of significant understanding of the importance of e-learning and its impact on the quality of instruction ( Mallinson & Krull, 2013 ). This phenomenon of resistance to the new teaching techniques was identified in many other e-learning initiatives and could significantly impact progress of the integration of technology into teaching practices as admitted by Moershell (2009) who also added another point in this regard which is the specific culture of the institution which can play a role towards reinforcing the resistance, in correlation with the individual’s nature of the employees, which tend to be uncooperative.

The majority of resistance literature is focused on its causing factors, specifically the adoption of online learning. Berge and Muilenburg (2001) identified 64 barriers or factors of resistance to distance education that were grouped into 10 factors. Harvey and Broyles (2010: p. 112) identified 20 factors of resistance and pointed out the antidotes to them.

3. Methodology

This research project used primarily a qualitative approach including data collected through three main instruments, interview protocol, observations and analysis of supporting and related documents. This study was developed with reliance on input collected in the form of interviews with students, deans, faculty members, and decision makers at ANU. Ten of the interviews were conducted in order to understand the vision of the university towards e-Learning. These interviews were conducted with university president, and Deans of faculties at the university. Each interview was open and lasted for one hour. What distinguished each interview was the concentration on the university policy, understanding and attitudes of the University for ELearning, its readiness for eLearning, obstacles and opportunities were also discussed. As the main author who is the director of eLearning center and the responsible person for capacity building of faculty members in eLearning, she was able to observe the training sessions and took notes of the faculty members who participated in the training and recorded their comments, practices and attitudes.

Analysis of policy document such as the University’s strategic plan, e-learning Center reports and surveys, as well as the minutes of e-learning workshops and meetings was also conducted. Finally, the lead investigator’s observations and daily experiences as the director of the e-Learning Center were also captured and reviewed as a historical log of events. Understanding the principal investigator was also a stakeholder in the change management process is one limitation of this research approach. The model is presented for consideration by other similar institutions undertaking this or related change management initiatives. Figure 1 illustrated the whole methodology section which is a representation for NNU emerging plan.

Figure 1. Emerged model.

4. Developing an E-Learning Strategy

As stated by Haugen (2004), E-learning projects are mostly without an effective pedagogical approach, which can reduce the potential of the learning process. Being an online teacher requires a lot of reflections on how to construct and run the course over the Internet. Many higher education institutions have not experienced the full potential of e-learning because the initial initiative overemphasizes the use of technology rather than the pedagogical advantages. Often, in these initiatives, little attention is given to change management strategies ( Mackenzie-Robb, 2004 ). Initiating a plan for e-learning and developing a model customized to the culture and history of ANU was a difficult and iterative process. Critical success factors had to be identified ( Engelbrecht, 2003 ) and challenges had to be discussed. The use of ICT (Information Computing Technology) had to be integrated into all levels of university management and processes in order for the strategy to conform to and fit the culture and vision of the university. This vision was reached after raising many questions and discussion took place in order to describe the future of e-learning at ANU. Some of these questions were:

・ Why does ANU need e-learning, to what outcome?

・ What form of e-learning suits our learner as well as our system?

・ How does ANU define e-learning?

・ Does ANU’s vision fit a national strategy supporting e-learning in Palestine?

・ Is e-learning visible and supported in ANU’s strategic plan?

・ Are there any national regulations that may impact e-learning at ANU?

・ What are the best practices in e-learning?

・ Are the units to be impacted by e-learning at ANU ready for e-learning?

・ Are faculties’ members and students ready for change brought on by e-learning?

・ Do we need to introduce an incentives program to stimulate the adoption of e-learning?

・ Can change happen quickly at ANU in regard to the introduction of e-learning?

・ Which is the best model for change management around this initiative?

・ What are the main challenges and threats to e-learning?

・ Are other departments already supporting e-learning at ANU?

・ How can we document and record our change management experience?

・ How many students should be enrolled in each e-learning course?

・ Do we need virtual spaces for synchronous meetings?

Many of the above-mentioned questions were answered. A few were still under discussion and in need of additional time and research in order to arrive at the most suitable approach. Lessons learned from the change management experience continued to influence forward progress. Capturing the most appropriate practices for ANU continued and would be disseminated in the coming few years. Plans were also being developed to gauge the impact of e-learning on learners’ achievements and students’ motivation.

A clear and concise vision for the e-Learning Center was developed through interviews, discussions, and roundtables with learners, faculties’ members, deans, and decision makers. The e-learning integration plan was articulated in a vision statement that sought to “integrate information and technology into learning in order to reach a highly competitive quality of teaching and learning outcomes among universities, national and international communities, and hence brought further knowledge to societies about the benefits of e-learning” ( ANU, 2016 ).

Eight main goals were developed in order to achieve the vision of e-learning:

1) To arrive to a high-quality education in both learning and teaching, in order to achieve the best education.

2) To compete locally and globally with the higher education institutions.

3) To meet the changing needs of today’s learners.

4) To improve the environment of e-learning.

5) To improve the quality of e-learning outcomes.

6) To enhance the capacity of instructors and learners in pedagogy.

7) To increase awareness towards e-learning.

8) To design high-quality blended courses.

These goals were the result of a SWOT analysis at ANU. The SWOT analysis was conducted with senior staff of the university through which, the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and challenges of ANU were analyzed and discussed with senior management level and with faculty members. Many strengths were identified through the initial conducted SWOT analysis. One critical strength was the awareness and readiness of the senior management at ANU to recognize the importance of integrating technology into teaching and learning. This was not strictly for the sake of the use of technology but rather for two important reasons: First, senior management recognized that the technology and information revolution had affected all aspects of higher education, and that ANU had the responsibility for their students and faculties to empower the ANU educational system with appropriate technology in order to be part of the digital world. Secondly, ANU was working toward excellence in teaching and learning and was hence concerned with its international reputation. For these reasons, the university desired to enhance the quality of instruction according to international quality standards. This enhancement would be achieved by utilizing different tools and strategies in teaching and learning to meet the needs of its learners and prepare them for today’s workplace.

The SWOT analysis also revealed tremendous e-learning opportunities at ANU. These included many dimensions, such as: the technological infrastructure of the university, especially evident in the new campuses design and construction. These opportunities increased in prominence with the emergence of a strategic plan that had already adapted e-learning into its strategic goals. Four of the main goals of ANU’s strategic plan reinforced the importance of e-learning; namely:

・ Provide ongoing training for faculty members on modern teaching methods.

・ Train faculty to use information technology in the educational process.

・ Encourage e-learning as a means of reinforcing the educational framework.

・ Implement regulations and instructions consistent with international quality standards such as Quality Matters.

This comes in addition to the previous experiences of many faculty members who have already participated in projects aiming at the design of online courses.

One of the main weakness or threats to this e-learning initiative was the resistance from faculties’ members to the use of modern methods of teaching and learning and a shift toward a more learner-centered approach. An additional threat was the lack of national rules and regulations for e-learning in Palestine. The limited financial resources also posed a major weakness at both ANU and at the national levels.

5. The Emerging Model for E-Learning at ANU

In arriving at this new model, Tony Bates’ model of planning for e-learning was reviewed, which proposed that the transformation into e-learning undergoes five consequential stages:

・ Stage 1 “Lone Rangers” ( Bates, 2000 ): These are the early adopters of e-learning. In their approach, e-learning is introduced through the initiative of individual faculty members or instructors, often with no immediate or direct support from the institution.

・ Stage 2 Encouragement: The activities of the early adopters attract the attention of senior administrators, who try to support them with small grants or a slightly reduced teaching load.

・ Stage 3 Chaos: After a period of time, a growing number of instructors embrace e-learning, but the administration begins to feel worried about issues of quality, duplication of effort, and lack of technical standards, such as the need to support different course development platforms, and above all, the costs of scaling up to large numbers of classes and instructors.

・ Stage 4 Planning: The senior administration realizes that priorities need to be set, common technical standards established, technical, design, support and training for faculty or instructors developed, and hence locating the most cost effective ways of developing e-learning so that both the budget and instructor workload can be controlled.

・ Stage 5 Sustainability: The institution has established a stable system of e-learning that is cost effective and scalable. Few institutions to date have reached this stage.” ( Bates, 2007: p. 48 )

The above model was studied and adopted as an initial frame with which to initiate the e-learning model. Following the SWOT analysis, a vital concern emerged: if ANU reaches the third stage of chaos based on the authors of previously documented experiences, there will be a great danger of not being able to move out of it. Therefore, a new model was designed with modifications to the model posed by Bates. The model is nick-named “Go with the horse that pulls”. This model involves six phases:

5.1. Raising Awareness

The first and most important phase is to raise awareness and to deploy an e-learning culture. This phase began with a structured orientation. Sixteen workshops in different faculties were conducted to answer the questions of why should e-learning be adopted? What does it mean? and are we in need of e-learning? 90% of each faculty members participated in each workshop. Calvo & Rungo (2010) in this regard emphasized the importance of the consensus of the institution in agreeing on the purpose of e-learning, for the purpose of building common understanding. As an initial step, a draft working paper was developed with suggested definitions for different conditions, and a workshop was held with the participants who included initiators, deans, directors, and vice presidents at ANU. Online learning, blended learning, enabled learning, synchronous learning, asynchronous learning, instruction design, multimedia, and learning management systems were discussed, and definitions for each were agreed upon. As a result, blended and enabled learning were chosen to be the most appropriate models for e-learning at ANU.

Blended learning was defined as the ability to deliver learning as both online and face to face with the percentage of 75% face to face and 25% online. All the course content would be designed online after being assessed. While enable learning mode was defined as the use of technology for communication between learners and their instructors in various ways, and a portion of the course content would be online. The above definitions were used specifically for this model at An-Najah National University.

Excellence in teaching and learning was the terminology used to express the university policy, despite the delivery method whether electronically or face to face. Many studies referred to this approach ( Fee, 2009: p. 13 ) and concluded that e-learning should not be distinguished from learning since it is simply another form of learning and consider it as a tool not a goal in itself. Questions arose as to whether e-learning was seen as supplementary or as a replacement to the traditional standards of teaching, and it was collectively agreed that e-learning should be integrated into learning based on content, learners’ needs, and the wishes of faculty members. Manuals, brochures, Web Pages and a Facebook page were developed for this purpose. Based on the workshops evaluation sheets, faculties’ members held positive attitudes toward e-learning, and the process continued.

5.2. Capacity Development

As emphasized by Rosenberg (2007) , this phase is the heart of change management having the right technology, the best content and skillful employees will not lead to success in e-learning. Faculty members, staff and deans are the key factors for successful transition, and it is essential to train them to become competent e-learning facilitators ( Engelbrecht, 2003: p. 38 ).

The philosophy behind the program involved beginning with aspiring individuals and leading young faculty members as the first adaptors of e-learning. Training workshops were optional and upon request. All training material entailed three themes: technical, pedagogy and spiritual aspects of e-learning, the entirety of which were developed in a way that concentrates on the knowledge, skills and attitudes of faculty and participants toward e-learning, which was viewed as key to moving forward. Best practice in adult learning was implemented where active learning strategies were implemented. The design of the program enables each faculty member to decide and choose how much they need to learn, and how much they want to learn. The program offers different options for learning, such as face-to-face workshops, self-running training courses, one to one training and peer-to-peer sessions.

Resistance to the model was ignored and instead a “go with the horse that pulls” strategy was emphasized. This strategy inhibits any unfruitful dialogue or discussion that may lead to nowhere in the e-learning process. Nonetheless, the opinions of faculty members were respected; but opponents to the model were informed that support would be given to them upon their request, when they feel they are ready to engage in e-learning. Success stories were deployed and discussed in the form of roundtables. An Incentives system was created and implemented, which included example rewards, acknowledgments, and various ceremonies. The idea was to encourage faculty members and to show them the benefits of e-learning, without putting pressure on them. After each workshop, more faculty members began to integrate technology into their teaching methods, which occurred in different levels and manners, such as in the form of self-directed pathways, and independent learners. McQuiggan (2012: p. 32) considers this as an important issue, especially among adult learners.

Training was not focused on how to teach online courses only but also on locating the best practice in teaching face-to-face, since teachers usually teach as they were taught, and training workshops were considered as an opportunity to learn about modern teaching strategies ( McQuiggan, 2012 ). All training courses were developed upon the feedback received in the reflection sessions, which bore in mind the perspectives of participants, in order to meet their needs. Different faculties proposed different needs and strategies. All training workshops were limited to 25 participants each, in order to give opportunities for discussion, two moderators led each workshop.

By the end of the first year (2013), 35% of faculty members were successfully trained on instructional design, moodle, social media, active learning, e-learning ethics, and authentic assessment, while over 70% of faculty members participated in the e-learning orientation workshops. As indicated in the evaluation sheet of the training workshops, over 80% of participants were satisfied with the training and have expressed a desire to participate in further advanced training workshops ( e-Learning Center, 2013 ). One important indicator of success was the shift from calling for the conduction of trainings from our side, to preparing training workshops upon the request of faculty. This shift was initiated by the faculty of engineers, where 25 faculty members participated in an all-day workshop during their weekend.

And by the end of year (2016), 82.1% of faculty members were successfully trained on instructional design, moodle, social media, active learning, e-learning ethics, and authentic assessment ( e-Learning Center, 2016 ).

5.3. Piloting-Designing and Implementing Blended Courses

This phase began with a call for faculty grants by the center for excellence in teaching and learning which the e-learning center worked cooperatively with. Fourteen courses were selected to be designed online and implemented as blended courses under the supervision of e-learning, excellence in teaching, and learning centers. The remaining 31 courses were designed, implemented, and evaluated according to specific criteria. Table 1 reveals the number of developed courses in the last year.

By the end of the second semester of the year 2015-2016, 1062 courses were designed, 121 courses were evaluated and taught as blended courses, while the rest are enabled courses through which the teacher can use moodle as an interactive learning environment in order to involve students in their learning process, which will be conducted in the form of forums, e-assignments, and quizzes.

Four courses were chosen as models to be accessed by faculty members in the training workshops. A team consisting of an instructional designer, a multimedia specialist, and a subject matter expert worked together to develop each course. The roles of each of the faculty members differed from one course to another according to the background of the subject matter expert and his interest in e-learning. In assigning these roles, more attention was given to the quality of the designed courses so as to raise the standards accepted by the second generation of e-learning designers.

5.4. Planning

A three-year action plan was developed which described the aims, activities, needs, and timeframe of the e-learning process and responsibilities. By the end of the third year, all faculty members would have been trained in e-learning, while reflecting on their traditional ways of teaching, thus enabling them to practice a new strategy of modern teaching that concentrated more on the needs of the learners, as well as on real life experiences, and technology would be suggested as an optional choice for them.

A variety of resources must be allocated for e-learning, as the first year of

Table 1. Online course distribution.

working with e-learning was with limited resources, which included the volunteering of all committee members in order to support the university in its transformation stage. Today, the e-Learning community is increasing gradually within the university, and the culture is quickly moving from one faculty to another through peer-to-peer support.

5.5. Assessment and Evaluation

An evaluation committee was formed for the purpose of evaluating the blended courses. The committee consisted of five members from different disciplines who have previous experience in evaluation, and have already designed taught blended courses. The committee began its tasks with developing their own evaluation criteria, which was carried out after studying and analyzing the available international criteria for assessing the quality of e-learning courses. These included the Penn State quality Assurance Standards and the Sloan Consortium scorecards for online courses.

The main themes of the criteria developed were the general layout and organization of the course; the intended learning outcomes related to course content; learning resources; language used; learning strategies―learner centered approach, accessibility and finally evaluation and assessment tools.

As part of this process, 121 courses were evaluated, and feedback was given to teachers and designers, while courses were improved upon the recommendations of the evaluation committee. The committee considered the evaluation aspect of the program as a learning process, since many issues arose during this process, which were negotiated throughout the discussions. One of the main important lessons learned from the observations of the committee was common misuse between the objectives and the intended learning outcomes among faculty members. As a result, a training workshop was established specifically for faculty in order to develop their skills in managing and designing their syllabus.

5.6. Generalization and Sustainability

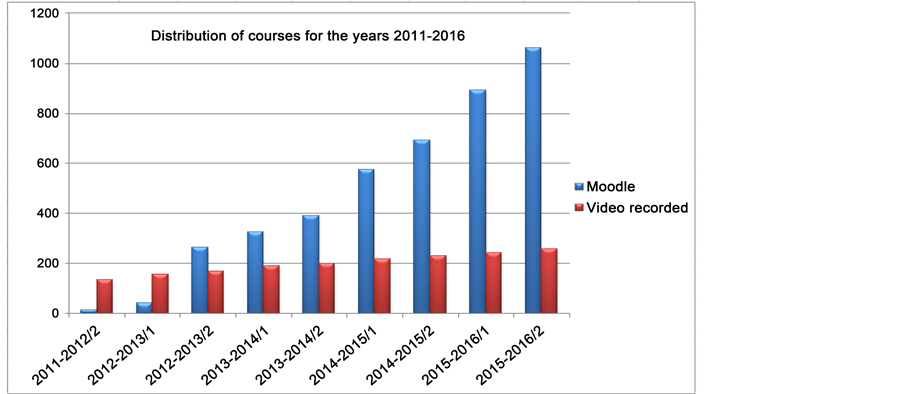

An-Najah National University looks forward to reaching this stage in the coming three years, as clearly indicated in its e-learning plan. One big indication that shows the university’s strive in this regard was the establishment of the e-Learning center which is responsible for following up the spread of eLearning for all the faculties. Besides, this centre is also responsible for capacity building of all staff members, administrative staff and students as well. A strategic plan for eLearning was developed and discussed and approved by the university policy makers. Resulting from the efforts of the e-learning centre at ANU willingness to integrate technology has been shown in the great number of courses that are run on the moodle. Figure 2 shows the increasing number of the distribution of e-courses per semester since the beginning of emerging e-learning.

6. Qualitative and Quantitative Indicators of Success

Table 2 shows all the events, training sessions, exams, the construction of

Figure 2. Distribution of courses per semester.

Table 2. Success indicators of the emerging model from 2012 until end of 2016.

e-courses along with incentives and awards being offered by the university to be as lain indicators of the university emerging model from 2012 until end of 2016.

7. Conclusion and Future Interventions

ANU is seeking to become a leader of blended learning in Palestine, and to develop a suitable learning environment for itself in both the real and virtual worlds. This paper presented the ANU experience of managing its shift to e-learning, and reported on its model in e-learning as a new and emerging one. Strengths and weaknesses were discussed, and future interventions were also explained. As planned for the future of e-learning at ANU, further research should be conducted to measure accurately the impact of e-learning on improving the general learning environment. Faculties at the university expressed a strong commitment to e-learning in different ratios, while some of them were still in need of further encouragement. Additional financial support is needed to be able to continue the work and to achieve the university’s excellence. Cooperation and support from different university units, centers, and faculties empowered the center of e-learning at ANU, and the center hoped to continue to receive such support and encouragement in order to achieve its objectives, and to establish a larger, more cohesive e-learning society in all parts of Palestine.

Acknowledgements

This research is dedicated to the memory of Bruce Chaloux whose encouragement and inspiration are the reason behind developing it. I first met Bruce in 2011 during teaching and learning conference held by An-Najah National University and Amideast, and since then he has continuously supported my efforts in establishing the e-learning center at An-Najah National University. His passing comes as a great loss to the entirely of online higher education systems across the world, and I will continue to follow through his footsteps in order to pursue his research and objectives in the fields of online learning.

Cite this paper

Affouneh, S. J., & Raba, A. A. A. (2017). An Emerging Model of E-Learning in Palestine: The Case of An-Najah National University. Creative Education, 8, 189-201. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2017.82016

References

- 1. An-Najah National University (ANU) (2011). Strategic Plan 2011-2016. Nablus: ANU. [Paper reference 1]

- 2. An-Najah National University, E-learning center plan (2013). [Paper reference 1]

- 3. An-Najah National University, E-learning center plan (2016). E-Learning Center Plan. The First Year Report of e-Learning Center. [Paper reference 2]

- 4. An-Najah National University (ANU). Official Website: http://www.najah.edu [Paper reference null]

- 5. Bates, T. (2007). Strategic Planning for E-Learning in a Polytechnic. Tony Bates Associates, Ltd. Canada.

https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-59140-950-2.ch004 [Paper reference 2] - 6. Berge, Z., & Muilenburg, L. (2001). Obstacle Faced at Various Stages of Capability Regarding Distance Education in Institutions of Higher Education: Survey Results. TechTrends, 45, 40.

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02784824 [Paper reference 1] - 7. Calvo, N., & Rungo, P. (2010). Analysis of Emerging Barriers for e-Learning Models: An Empirical Study. European Research Studies, V. XIII, (4). [Paper reference 1]

- 8. Engelbrecht, E (2003). A Look at e-Learning Models: Investigating Their Value for Developing an e-Learning Strategy. Progressio, 25, 38-47. [Paper reference 2]

- 9. Fee, K (2009). Delivering E-Learning A Complete Strategy for Design, Application and Assessment. Kogan Page. London and Philadelphia. [Paper reference 1]

- 10. Mackenzie-Robb, L. (2004) E-Learning and Change Management—The Challenge. Vantaggio Ltd. England. [Paper reference 1]

- 11. Mallinson, B., & Krull, G. (2013). Building Academic Staff Capacity to Support Online Learning in Developing Countries. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 17, 63-72. [Paper reference 1]

- 12. McQuiggan, C. (2012). Faculty Development for Online Teaching as a Catalyst for Change. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 16, 27-61. [Paper reference 2]

- 13. Rosenberg, M. (2007). The Handbook of e Learning Strategy (edited by B. Brandon). Santa Rosa, CA: The eLearning Guild. [Paper reference 1]