Communications and Network

Vol.09 No.01(2017), Article ID:72599,26 pages

10.4236/cn.2017.91002

An Integrated Model of Job Involvement, Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment: A Structural Analysis in Jordan’s Banking Sector

Ayman Bahjat Abdallah, Bader Yousef Obeidat, Noor Osama Aqqad, Marwa Na’el Khalil Al Janini, Samer Eid Dahiyat

Business Management Department, School of Business, The University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan

Copyright © 2017 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: November 11, 2016; Accepted: December 4, 2016; Published: December 7, 2016

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this research is to investigate the interrelationships among the three behavioural constructs of job involvement, job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Accordingly, a structural model is developed to delineate the interactions among these constructs and explore the mediating effect of job satisfaction on the relationship between job involvement and organizational commitment. A questionnaire-based survey was designed to test the aforementioned model based on a dataset of 315 employees working in twelve out of twenty six banks operating in the capital city of Jordan, Amman. The model and posited hypotheses were tested using structural equation modelling analysis. The results indicated that job involvement positively and significantly affects job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Additionally, job satisfaction proved to be positively related to organizational commitment. Furthermore, job satisfaction positively and significantly partially mediated the relationship between job involvement and organizational commitment.

Keywords:

Job Involvement, Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment, Structural Equation Modelling, Jordan

1. Introduction

The bases upon which business sustainability and competitiveness can be built have fundamentally shifted from tangible to intangible resources. In particular, knowledge-based resources, capabilities and competencies reflected in an organization’s intellectual capital are increasingly defining today’s “knowledge economy” [1] [2] . Therefore, organizations are turning their focus to their human, intellectual, knowledge management and information system resources in recognition of their vital role as a driving force behind their success and the sustainability of their competitive advantage [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] , and encouraging innovation practices [8] [9] . Therefore, organizations strive to develop a committed workforce by adopting the best methods to ensure employee retention [10] [11] . An example of such methods includes the ability of organizations to adopt positive organizational attitudes such as job involvement and job satisfaction [12] . Furthermore, having a motivated, involved, and committed workforce is considered an important asset to an organization’s success as keeping employee motivation, commitment and job involvement up leads to improved productivity and lower turnover rates [13] [14] .

Job involvement has attracted attention as a key contributing factor to an organization’s success. According to [15] , job involvement is seen as means of aiding productivity and creating work situations in which individual and organizational goals are integrated. This involvement leads to enhanced satisfaction and increased productivity for the organization. Job involvement has also been reported to be a top organizational priority as fostering employee involvement can enhance an organizational effectiveness [16] . Given that job involvement and organizational commitment are considered two factors of vital importance for organizations to function properly and survive in today’s ever changing environment, this research will focus on investigating these concepts and the relationship between them. Moreover, job satisfaction is chosen as another factor to be investigated in terms of its mediating influence on the relationship between job involvement and organizational commitment as several studies have stated the importance of job satisfaction for organizational commitment and overall organizational performance.

The banking sector in Jordan is considered to be one of the most important sectors as it accounts for approximately 11.6% of the GDP [17] . However, business organizations today operate in an environment characterized by constant change and some of the challenges Jordanian banks face include globalization, the emergence of financial innovations, and heightened competition which have forced the management of such organizations to develop their human resources in particular and their organizational resources in general in order to adapt to the surrounding environment and sustain their competitiveness [18] [19] [20] . Given all these challenges, some researchers have reported that the commitment of organizational members is declining in both service and manufacturing organizations which have created the need for structural and relational changes [21] by adopting modern management techniques [20] . This is supported by [22] who stated that many banks are focusing their attention on the organizational loyalty of their employees as it is reported that banks with highly committed and loyal employees are effective banks that achieve their desired goals, significant profits and the highest performance, and enhance their competitive advantage. This argument is derived from the fact that retaining qualified employees in banks leads to retaining discerning customers. However, according to [21] , some of the programs adopted by organizations have failed to provide employees with the satisfaction and commitment required to retain customers who inherently influence the survival of service organizations. Therefore, organizations especially banks need to find ways to maintain the commitment and satisfaction of their staff by investigating the notions of job involvement, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment in order to survive and succeed. These factors may affect work-related behaviours as wok effort, organizational loyalty, job performance, absenteeism, intention to leave, and turnover [23] [24] [25] [26] . Most existing studies were undertaken in the western business context. It is important for organizations to determine whether the concepts and conclusions regarding job involvement and organizational commitment hold true in other cultural contexts [27] [28] [29] . Furthermore, the literature regarding organizational commitment in the Middle East in general and in Jordan in particular is noticeably scarce [30] [31] [32] . Therefore, it is important to shed light on the relationships among job involvement, job satisfaction and organizational commitment in the context of the Jordanian working environment. Another issue raised in the literature is the lack of discriminant validity among the constructs of job involvement, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment [33] [34] [35] . The current study contributes to the literature by providing sufficient evidence of discriminant validity among the three constructs confirming, thus, that the three constructs are dissimilar and different.

This study attempts to address the gaps raised in the literature by examining the effect of job involvement on job satisfaction and organizational commitment in banks in Jordan. Additionally, the effect of job satisfaction on organizational commitment is investigated. Furthermore, the mediating effect of job satisfaction on the relationship between job involvement and organizational commitment is examined.

1.1. Job Involvement

Job involvement refers to how people perceive their jobs in relation to the working environment, the job itself, and how their work and life are integrated [36] . Also, job involvement can be viewed as a psychological condition wherein an employee “is cognitively preoccupied with, engaged in, and concerned with one’s present job” [37] . One of the early definitions of job involvement was proposed by [38] who defined job involvement as “the level to which an employee is identified psychologically with his job or the importance of job in his total self-image”. There is a general consensus among researchers that employees with a high level of job involvement would place their jobs at the centre of their overall interests [39] . On the other hand, employees with low levels of job involvement concentrate on other interests rather than their jobs [40] , and will be less creative and innovative [41] . Additionally, [42] argued that employees with “high job involvement are more independent and self-confident―they not only conduct their work in accordance with the job duties required by the company but are also more likely to do their work in accordance with the employees’ perception of their own performance” (p. 478).

Employees with high levels of job involvement tend to see their jobs as central to their personal character and focus most of their attention on their jobs [43] . Job involvement is highly effected by the work environment as it makes one believe that one’s work is meaningful, offers control over how work is accomplished, maintains a clear set of behavioural norms, makes feedback concerning completed work available, and provides supportive relations with supervisors and co-workers [44] . Though [45] pointed to the similarity of the constructs of job involvement and organizational commitment as both are associated with worker’s identification with the job experience; however, the two constructs differ. Job involvement is more associated with identification with worker’s immediate job activities while organizational commitment is more associated with worker’s attachment to the organization [44] .

1.2. Job Satisfaction

Researchers such as [46] suggested that the investigation of the concept of job satisfaction began in 1918. However, others mentioned that the examination of the role of work attitude began in 1912 and was highlighted by the Hawthorne studies in 1920 and eventually a systematic approach to studying job satisfaction was initiated in the 1930s [47] . Job satisfaction is considered an important concept to study as it is relevant both to the humanitarian perspective and utilitarian perspective. The humanitarian perspective revolves around the premise that level of employee satisfaction refers to the extent that employees are being treated fairly and appropriately in the organization. The utilitarian perspective suggests that employee satisfaction can lead to behaviours that influence the functioning of the organization [48] .

There have been many ideas about what the concept of job satisfaction actually refers to, but researchers have failed to agree on one definition or factors that measure this concept. One reason that the concept of job satisfaction is so complicated to define and measure relates to the various factors that can contribute to one being satisfied in his or her work [49] . While on the surface job satisfaction seems to be straightforward, it is actually a very complex idea with a number of aspects to that must be addressed [49] . According to [50] job satisfaction is a measureable representation of an affective reaction to a particular job that is the individual’s satisfaction with his or her job. Other definitions include [47] who asserted that job satisfaction is a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job. It can also be defined as the general attitude that the employee has towards her job and is directly tied to individual needs including challenging work, equitable rewards and a supportive work environment and colleagues [51] . [52] defined job satisfaction as a personal evaluation of conditions present in the job, or outcomes that arise as a result of having a job. [53] defined job satisfaction as a collection of feelings that an individual holds towards his or her job. [54] defined job satisfaction as the attitudes and feelings people have about their work where positive attitudes indicate job satisfaction and negative attitudes indicate job dissatisfaction.

Job satisfaction is usually measured using the three types of job satisfaction which include: intrinsic, extrinsic, and general reinforcement [55] . Intrinsic satisfaction refers to how people feel about the nature of the job tasks themselves. Here personal factors that focus on individual attributes and characteristics are the essence of intrinsic satisfaction [50] [56] . In order to evaluate intrinsic satisfaction we need to address some key factors such as creativity, achievement, morale values, independence and authority. Extrinsic satisfaction refers to how people feel about aspects of the work situation that are external to the job tasks or the work itself [50] . Extrinsic satisfaction is usually influenced by environmental factors that are associated with the work itself or the work environment [56] . The factors that must be addressed to evaluate extrinsic satisfaction are advancement, company policy, compensation and recognition. Finally there is general satisfaction which is the combination of the both intrinsic and extrinsic dimensions in addition to two other dimensions which are working conditions and co-workers [57] . Job satisfaction can encompass many concepts and plays an important role in many of the things that are important in our life not only as individuals but also as a society. We should not underestimate the importance of being satisfied with one’s work, which has a strong role in defining one’s identity and position within our society [49] . According to [58] job satisfaction is one important dimension of individual’s happiness at work, as most people spend large amounts of time at their work. In this study, job satisfaction is measured in terms of intrinsic satisfaction and extrinsic satisfaction.

1.3. Organizational Commitment

Organizational commitment has always been a concept of interest to researchers but its importance has risen considerably as a result of the changing employment practices [59] . This has given employees the green light to move from one organization to another and not be constrained by the feeling of remaining in one organization for an extended period of time. However, finding qualified and skilled replacements for these employees is considered a difficult task for organizations [12] . As a result, organizational commitment has taken centre stage as a concept of absolute importance for organizations. A variety of definitions and measures for organizational commitment have been proposed over the years. [60] was the first to provide a definition for commitment. In his study, he used the theory of side-bets to refer to commitment, according to this theory employees accumulate investments, either hard or soft, that motivate them to remain in their post as they would be lost if they were to leave the organization. The next study was conducted by [61] as they defined organizational commitment as the likelihood to prescribe to organizational values; exert effort to adhere to these values; and the desire to remain part of the organization. Perhaps the simplest definition of organizational commitment is provided by [62] who referred to it as an employee’s attachment to the organization or its dimensions.

Organizational commitment has also been defined as “a force that binds an individual to a course of action that is of relevance to one or more targets” [63] . [64] used this term to define organizational commitment as composed of three characteristics which include: 1) a strong belief in and acceptance of the organization’s goals and values 2) willingness to exert considerable effort on behalf of the organization 3) a strong desire to maintain membership in the organization. Later, [65] proposed a multidimensional three-component model to conceptualize organizational commitment which is considered to be one of the most widely recognized and accepted approaches in the organizational commitment literature [66] . According to [65] the three components are: affective commitment (the desire mind-set)which refers to the extent to which employees identify with, are emotionally attached, and are involved in the organization, continuance commitment (the perceived cost mind-set)refers to an employee’s awareness of the costs associated with leaving the organization, and normative commitment (the obligation min-set) reflects a feeling of obligation to remain in an organization, It develops as the result of a moral obligation to repay the organization for benefits [48] [67] .

Organizational commitment has been reported to provide many benefits for organizations; therefore interest in this concept continues to grow day after day [68] . Some of these benefits include; lower turnover, higher job effort and performance, increased organizational citizenship, increased attendance and productivity, increased organizational effectiveness and gaining a competitive edge [69] [70] [71] . Given the benefits associated with organizational commitment, organizations must strive to investigate the factors that can increase or decrease employees’ organizational commitment. For the purpose of this study, [65] model of organizational commitment will be used as a basis for measuring organizational commitment. This model consists of affective commitment, continuance commitment, and normative commitment.

1.3.1. Affective Commitment

Affective commitment is considered to be the core component of organizational commitment as it is the component most strongly associated with other organizational outcomes [71] . Affective commitment refers to the emotional attachment employees have with their organizations. Here employees stay in the organization because they want to and thus are highly motivated to achieve the organization’s goals because they deem as their own goals [72] . This component reflects the degree to which an individual feels part of the group and is satisfied with the involvement in the organization [73] . All in all, affective commitment includes the affective attachment, identification, involvement with the organization and employees’ desire to be part of the organization [74] .

1.3.2. Continuance Commitment

In this component individuals are committed to the organization because of extraneous interests not because of a general positive feeling [66] . Continuance commitment refers to the knowledge of the costs associated with leaving the organization. Here employees stay with the organization because they need to [75] . This results from either the fact that rewards associated with staying with the organization outweigh the cost of leaving or because the cost of leaving are greater that the reward of leaving the organization [73] . Thus, a more comprehensive definition of continuance commitment can be concluded where it refers to the attachment based on the financial and non-financial investments that an employee would sacrifice by leaving the organization [76] .

1.3.3. Normative Commitment

Normative commitment refers to an employee’s obligation to remain in the organization as a moral duty [28] . Here employees stay with the organization because they ought to [73] . This belief represents a min-set of obligation toward remaining in the organization in order to reciprocate organizational investments or as a result of socializing the belief of maintaining loyalty to an organization [74] .

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Research Framework

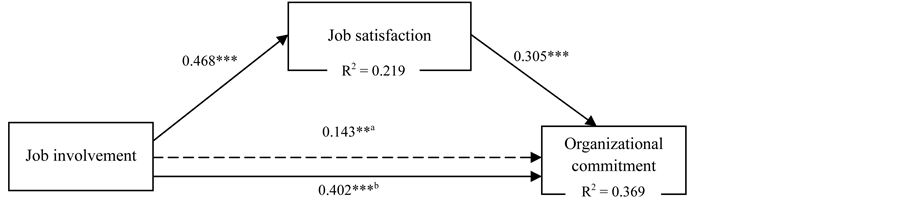

This research is based on the proposed framework (Figure 1). The framework considers the effect of job involvement on job satisfaction and organizational commitment. The framework also considers the effect of job satisfaction on organizational commitment. The mediating effect of job involvement on organizational commitment through job satisfaction is also considered.

2.2. Job Involvement and Organizational Commitment

Job involvement affects different organizational behaviours such as absenteeism and turnover, organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and others. For example, [77] reported that job involvement is related to organizational commitment and low job-involved employees have been hypothesized to be more likely to leave the organization and withdraw their energy from the job and apply it outside the realm of work or invest it in undesirable on-the job activities. Furthermore, [78] stated that individuals with high levels of job involvement are likely to have increased affective organizational commitment as they believe they need to repay the organization for all benefits it has provided them. In addition, [79] suggested that job involvement is negatively associated to intention to quit and positively associated with job satisfaction and organizational climate perceptions.

Figure 1. Theoretical framework.

[80] suggested that a person’s organizational commitment is influenced by the level of organizational and managerial support, employee involvement in decision making, feedback regarding job performance, leadership behaviour and organizational culture. In addition, [81] stated that the jobs and behaviours of employees and socio-cultural environment of the organization influence organizational commitment. Furthermore, [82] argued that employee commitment can be increased through reward, recognition, better remuneration, and a better work environment. It should be noted that job involvement is not expected to positively affect organizational commitment in all situations. [83] argued that there may be cases when worker is highly involved in a specific work but not be committed to the organization or vice versa. Existing literature provides sufficient empirical evidence on the effect of job involvement on organizational commitment and other organizational outcomes such as turnover intention, productivity, job migration, and professional commitment [84] - [90] .

H1: There is a positive effect job involvement on organizational commitment.

2.3. Job Involvement and Job Satisfaction

Job satisfaction is highly influenced by job involvement. This is due to the fact that highly involved employees are more satisfied with their jobs than low involved employees [91] . [16] found that job involvement was positively related to job satisfaction and organizational commitment. He concluded that employees who are involved in their jobs are likely to be satisfied with their jobs and hence become committed to their organizations. [92] also revealed that high job involvement will result in higher levels of job satisfaction and by extension high intention to stay with the organization. Additionally, [44] and [93] argued that employee job involvement will positively affect work behaviours that are associated with job satisfaction such as employees’ motivation and effort. Furthermore, job involvement affects organizational citizenship behaviours which is reflected by committed employees that are willing to assist specific others in the organization, or the organization in general [94] . Job involvement enhances social contact and social recognition, boosts a personal sense of coherence, increases confidence of better career prospects, and reduces uncertainty in the job environment [95] . Additionally, Job involvement includes higher employee participation, discretion, and autonomy which boost feelings of self-esteem, responsibility, achievement and purposefulness at work increasing, thus, job satisfaction [96] [97] . Moreover, job involvement enhances the feeling of empowerment and freedom to employees which lead to higher job satisfaction [98] .

H2: There is a positive effect of job involvement on job satisfaction.

2.4. Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment

Job satisfaction and organizational commitment are considered important factors in determining employees’ contribution to the organization and their intention to stay in it [80] .

The importance of job satisfaction and organizational commitment has been demonstrated in many studies. For example, [49] found that satisfaction and commitment contribute to the efficiency of organizations by influencing issues such as performance, productivity, absenteeism, deviant activity, and withdrawal behaviours. This is supported by [99] who reported that employee satisfaction influences productivity. According to them, employees choose to either fully give their services to the organization or not depending on how they feel about the job, pay, promotion, managers and co-workers. [66] reinforces this by noting that job satisfaction affects the productivity of organizations by maintain high performance and efficient services. [100] studied patients’ attitudes toward service quality and its impact on their satisfaction at three hospitals located in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; and found that service quality dimensions have a positive impact on patients’ satisfaction. Also, the study found a statistically significant impact of tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance and empathy on patient satisfaction. [14] , using a sample of 247 middle-level managers in the banks, and the IT sectors, found that job satisfaction is positively related to organizational commitment. He also found that managers with internal locus of control are more satisfied with their jobs and hence they are more committed towards their organizations. [101] studied the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment and the impact of demographic key variables on job satisfaction and organizational commitment. The study was conducted on a sample of 156 employees working in a private financial institution in Bahrain. Results showed that job satisfaction and organizational commitment are positively related and that age was the only demographic key variable that affected organizational commitment. Other empirical studies have also found positive effect of job satisfaction on organizational commitment [66] [73] [102] [103] [104] [105] .

H3: There is a positive effect of job satisfaction on organizational commitment.

2.5. Mediating Effect of Job Satisfaction on Job Involvement and Organizational Commitment

Job involvement is considered an important factor that influences both job satisfaction and organizational commitment as argued by [35] who suggested that the variables of job satisfaction, job involvement, and organizational commitment are found to be always associated with each other. Organizations should exploit job involvement to enhance job satisfaction, which in turn supports organizational commitment. [106] , using a sample of 600 diesel locomotive works in India, found a positive effect of job satisfaction on organizational commitment. They also found that job involvement positively moderates this relationship. Job satisfaction has been a major research topic for many years, and has been described as the employee asset [107] . This interest is derived from the notion that satisfied employees will be more loyal, productive and efficient with lower intention to leave the organization. Job involvement enhances job satisfaction by increasing personal sense of coherence and social recognition and increasing uncertainty in the career prospects [95] . Well involved employees will have higher levels of job attention, satisfaction and performance [102] . This will affect the effectiveness of work autonomy, and employees with a high level of job satisfaction will be more intrinsically motivated and thus more efficient when performing in autonomous situations [108] .

H4: Job satisfaction positively mediates the relationship between job involvement and organizational commitment.

3. Methodology

3.1. Survey

A survey questionnaire was designed to collect primary data for the current study. The study’s constructs were adopted from the existing literature. The survey was first drafted in English language and then translated into Arabic. Both versions were reviewed by seven professors in Business Administration, and necessary revisions were made accordingly. Additionally, the survey was pre- tested by four employees from different banks to improve understandability of the question items. Subsequently, the finalized version of the survey was prepared.

The population for study consisted of all banks operating in Jordan. The banking sector is considered to be one of the most important and influential sectors in the Jordan. This sector currently consists of 26 banks which include 22 commercial banks and 4 Islamic banks. Twelve banks agreed to participate and provided the authors with the necessary access to distribute the questionnaires. Unit of analysis consisted of individual employees working in the targeted banks. This is due to the fact that the main objective of the study is to examine the commitment of employees to their organizations based on their levels of job involvement and job satisfaction. The total number of employees working in the banking sector in Jordan is 17,840 [109] . The appropriate sample size for this population is approximately 377 [110] . We targeted 450 respondents to ensure good representation of our sample. Each bank assigned one officer from the human resource department to distribute the survey to randomly selected employees. The process of data collection lasted for about two months and ended in June, 2016. Finally, we received 352 questionnaires. 37 questionnaires were defined as unusable due to missing data or other problems. The final number of usable questionnaires was 315 representing a response rate of 70%. This rate is relatively high compared with other empirical studies conducted in Jordan. For example, [111] got a response rate of 57.7%, [32] showed a response rate of 52%, and [112] received a response rate of 59.5%.

3.2. Measures

The constructs for this research were adopted from the literature. Job involvement construct was adopted from [92] and consisted of 10 question items. Job satisfaction included two dimensions, intrinsic job satisfaction and extrinsic job satisfaction. Intrinsic job satisfaction construct included 12 items and was adopted from [55] . Extrinsic job satisfaction construct was also adopted from [55] and included 8 items. Organizational commitment was measured using three dimensions, affective commitment, continuance commitment and normative commitment. The three constructs were adopted from the model proposed by [113] and each construct included 8 question items. For job involvement and organizational commitment, respondents were asked to evaluate their agreement or disagreement with the statements provided using 5-point Likert scale where 5 indicated strong agreement and 1 indicated strong disagreement. For job satisfaction statements, respondents were asked to evaluate their feelings on their present jobs using 5-point Likert scale where 5 indicated very dissatisfied and 1 indicated very satisfied. Early and late responses were compared using t-test in order to test non-response bias [114] . No significant differences were found between the two groups indicating that our study is not affected by non-response bias. Also, Harmon’s single factor test [115] was performed to evaluate common method variance (CMV). All question items were simultaneously entered into a factor analysis using principal components and no rotation method. The results revealed eight factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0. The eight factors accounted for 70.40% of the variance and the first factor (the largest) accounted for 30.095% indicating that the data were not affected by CMV.

3.3. Validity and Reliability

Construct validity was assessed using exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. First, exploratory factor analysis was performed with promax rotation method and principal component analysis. We entered all the question items simultaneously. Due to the large number of items, many items showed cross- loadings and were deleted. Additionally, some items showed factor loadings less than 0.40 and were also deleted. Finally, we got six distinct factors as was initially expected. Eigenvalues for the six factors were greater than 1.0. Cronbach’s α-co- efficient was applied to test the reliability of the constructs. The reliability of the constructs including the overall constructs of job satisfaction and organizational commitment was satisfactory with α > 0.60 indicating acceptable internal consistency [116] . Next, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was applied based on the output of EFA using Amos 20. We had to further delete some question items to improve model fit indices. The final question items of each measurement scale are shown in Table 1 below. The fit indices of the final model using first order constructs showed satisfactory levels (X2 = 248.879; d.f. = 174; X2/d.f. =1.430; GFI = 0.910; CFI = 0.974; NFI = 0.920; NNFI = 0.969; RMR = 0.049 and RMSEA = 0.043). The normed chi-square of 1.430 was below the maximum value of 3.0 [117] . Goodness-of-fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), normed-fit index (NFI) and non-normed fit index (NNFI) were higher than the recommended minimum value of 0.90 [118] . Root mean square residual (RMR) was 0.049 and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was 0.043 implying satisfactory level of unidimensionality and convergent validity [118] [119] . Furthermore, the standardized coefficients for all the question items were

Table 1. Final measurement items.

higher than twice of their standard errors, providing additional support for convergent validity [120] . Besides, the factor loadings of all the items were greater than 0.50. In addition, average variance extracted (AVE) values for all the measurement scales were higher than 0.50 providing additional evidence of convergent validity [121] . The composite reliability of all the scales was greater than 0.70 providing a satisfactory level of reliability [118] [121] .

CFA analyses were repeated using second order factors of job satisfaction and organizational commitment. The final model fit indices using second order constructs (job satisfaction, job involvement and organizational commitment) fitted the data well (X2 = 280.763; d.f. = 181; X2/d.f. = 1.551; GFI = 0.898; CFI = 0.965; NFI = 0.909; NNFI = 0.959; RMR = 0.077 and RMSEA = 0.049). These indices indicated an acceptable level of unidimensionality and convergent validity. Also, the standardized coefficients of all the constructs were higher than twice of their standard errors, providing evidence of convergent validity [120] . Moreover, all the factor loadings were higher than 0.50. Likewise, average variance extracted (AVE) values for all the constructs exceeded 0.50 supporting the convergent validity [121] . The composite reliability of the two second order constructs exceeded 0.70 indicating sufficient levels of reliability [118] [121] . Table 2 shows the standardized factor loadings of EFA and CFA, Cronbach’s alpha values and composite reliability of the first and second order constructs.

Discriminant validity was assessed by ensuring that the square root of each AVE value is greater than the absolute correlation value between that scale and other scales. All first and second order constructs met this criterion providing sufficient evidence of discriminant validity [121] . In addition, The AVE value for each construct was higher than maximum shared squared variance (MSV) and average shared squared variance (ASV) values providing further evidence of discriminant validity [116] . Table 3 reports discriminant validity results for first order constructs and Table 4 reports the results of the final model with second order constructs.

4. Results

Structural equation modeling using Amos 20 was performed to test the study hypotheses. SEM allows simultaneous testing of all hypotheses including direct and indirect effects. Additionally, SEM has the option of applying bootstrapping re-sampling approach to test the mediating effect. Bootstrapping is superior to the approach described by [122] as normal distribution assumption of the indirect effect is not required and the accuracy of the results is not affected by the sample size [123] . As recommended by [124] , we selected 5000 bootstrap samples with 99% bias-corrected confidence intervals. An alternative hypothesis regarding the mediating effect is accepted if the lower and upper bounds of confidence intervals do not contain zero. This implies that the indirect effect is not zero with 99% confidence level. If the two bounds contain zero, then the alternative hypothesis is rejected [124] .

The results of the direct effects show that job involvement is positively and significantly related to organizational commitment (β = 0.402, P < 0.000), therefore hypothesis H1 is supported. Also, job involvement is positively and significantly related to job satisfaction (β = 0.468, P < 0.000), so hypothesis H2 is also supported. The direct effect of job satisfaction on organizational commitment is also positive and significant (β = 0.305, P < 0.000), therefore hypothesis H3 is supported. As for the mediating effect, the bootstrapping results show that the standardized indirect effect of job involvement on organizational commitment through job satisfaction is 0.143 with confidence intervals between 0.055 and

Table 2. Reliability and validity of the constructs.

aSecond order constructs; bSecond order indicators.

Table 3. Means, standard deviations, AVE, MSV, ASV and correlation matrix of first order constructs.

Notes: Square root of AVE is on the diagonal.

Table 4. Means, standard deviations, AVE, MSV, ASV and correlation matrix of second order constructs.

Notes: Square root of AVE is on the diagonal.

0.276. As these confidence values do not contain zero, hypothesis H4 is supported. Figure 2 illustrates direct and indirect models. Table 5 provides summary of the tested hypotheses.

5. Discussion, Implications, and Limitations

5.1. Discussion and Conclusions

This study is based on the premise that an organization’s intellectual capital is its most important asset. Thus, gaining employees commitment to their organization’s goals is believed to unlock their potential and achieve heightened levels of performance [125] . Accordingly, this study was conducted with the aim of investigating the impact of job involvement on organizational commitment through job satisfaction as a mediator variable in Jordanian banks. The premise behind this is that organizational commitment is considered a crucial component to the survival of organizations as it influences various outcomes such as productivity and overall performance. Therefore, a major objective of the study was to determine whether job involvement had an influence on organizational commitment and whether the presence of job satisfaction as a mediator influenced the relationship. First, the direct effect of job involvement on organizational commitment was examined. The findings have shown that a significant positive effect does exist of job involvement on organizational commitment. This result is in line with some previous studies [101] [103] [105] . The result indicates that the more employees identify psychologically with their jobs, where their perceived performance is important to their self-worth, the more they can identify with their respective organizations’ goals (i.e. the more committed they will be to their banks). As a result, it is believed that such commitment will be translated into enhanced levels of productivity [53] . This implies that when employees feel engaged in and concerned with their jobs, they will become more loyal, attached, and committed to their work and by extension to their organization [83] .

The results also revealed a positive effect of job involvement on job satisfaction indicating that employees who are involved with their jobs tend to exhibit satisfaction in their jobs. The result is consistent with the results obtained in some previous studies [16] [96] [97] [98] [126] . Employees with high levels of job participation and involvement have higher social recognition, self-esteem, freedom and empowerment, which lead to higher levels of job satisfaction.

Figure 2. Job involvement-job satisfaction-organizational commitment model. Note: ***: p < 0.001;**: p < 0.01; a: indirect effect; b: direct effect.

Table 5. Summary of results.

Notes: ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; JI: job involvement, JS: job satisfaction, OC: organizational commitment.

Managers in the Jordanian banks should place extra emphasis on increasing employee job involvement in order to enhance job satisfaction. The effect of job satisfaction on organizational commitment was also found positive and significant. This result is in line with some previous studies [66] [103] [104] . This implies that when employees are dissatisfied with their work, they are less committed and will search for other opportunities in order to quit, and if opportunities are not available employees may become emotionally or mentally disconnected from the organization. Furthermore, employees may like or dislike their jobs according to the conditions available to them which in turn may influence their intention to stay in the organization [48] . Job satisfaction leads to enhanced efficiency and productivity through positive and desirable work values [102] . Having committed employees and retaining them by sharing knowledge among them could reduce the costs associated with training and development, recruitment process, loss of business opportunity, loss of productivity and poor customer relationships [127] - [133] . Therefore, employee satisfaction should be given the greatest priority in order to enhance employee commitment which, ultimately, will improve job and organizational performance. Lastly, the results indicated a positive and significant effect of job satisfaction on the relationship between job involvement and organizational commitment. This implies that the full potential benefits of job involvement on organizational commitment are enabled through job satisfaction. Both job involvement and job satisfaction should be considered by managers as enablers of organizational commitment. Employees should be involved in their jobs in such a way that assures increasing their satisfaction and commitment.

5.2. Managerial Implications

The results of the study pointed to some recommendations for Jordanian banks as the study was conducted on the banking sector operating in Jordan. Most banks in Jordan employ thousands of employees. As banks expand so does the population of their staff and many issues related to employees are pushed aside and replaced by more pressing matters such as company growth and maximizing profits which eventually leads to the loss of touch with employees [21] . Managers are advised to pay close attention to the needs of their workers in order to increase their involvement which will ultimately lead to increased organizational commitment. This can be achieved by introducing human resource practices that increase the levels of job involvement and job satisfaction among employees and hence improve their commitment to the organization. In particular issues like relationships between co-workers, the competence of the supervisor and the ability to become someone in the community are matters that affect satisfaction of employees working in the banking sector in Jordan, therefore focusing on these issues can increase job satisfaction and in turn organizational commitment of employees.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

In research perfection is impossible, and this study is no exception. Numerous limitations are connected with research. Such limitations are provided below to increase the validity of the findings of future research. The first limitation revolved around the time allotted for completing the study. Having more time would allow for an increase in the number of questionnaires distributed thus increasing the sample size and improving the generalizability of the study results. Second, this study focused on the banks operating in the capital city of Jordan, Amman and did not take into consideration other parts of the country. Third, a quantitative technique was used as the main method to collect and analyze the data which might be considered as a limitation of this study. More qualitative techniques such as case studies are needed to get more accurate insights concerning the proposed relationships. Finally, banks were used as the population from which data was be collected. This might led to generalizability problems since banks have their own way of carrying out their business. Future research that focuses on more industries and investigates more associations toward organizational commitment such as knowledge sharing is recommended to overcome the issue of generalizability.

Cite this paper

Abdallah, A.B., Obeidat, B.Y., Aqqad, N.O., Al Janini, M.N.K. and Dahiyat, S.E. (2017) An Integrated Mo- del of Job Involvement, Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment: A Structural Analysis in Jordan’s Banking Sector. Com- munications and Network, 9, 28-53. https://doi.org/10.4236/cn.2017.91002

References

- 1. Masa’deh, R. and Shannak, R. (2012) Intermediary Effects of Knowledge Management Strategy and Learning Orientation on Strategic Alignment and Firm Performance. Research Journal of International Studies, 24, 112-128.

- 2. Dahiyat, S.E. (2015) An Integrated Model of Knowledge Acquisition and Innovation: Examining the Mediation Effects of Knowledge Integration and Knowledge Application. International Journal of Learning and Change, 8, 101-132.

https://doi.org/10.1504/IJLC.2015.074064 - 3. Altamony, H., Masa’deh, R., Alshurideh, M. and Obeidat, B. (2012) Information Systems for Competitive Advantage: Implementation of an Organisational Strategic Management Process. Proceedings of the 18th IBIMA Conference on Innovation and Sustainable Economic Competitive Advantage: From Regional Development to World Economic, Istanbul, 9-10 May 2012.

- 4. Shannak, R., Masa’deh, R., Obeidat, B. and Almajali, D. (2010) Information Technology Investments: A Literature Review. Proceedings of the 14th IBIMA Conference on Global Business Transformation through Innovation and Knowledge Management: An Academic Perspective, Istanbul, 23-24 June 2010, 1356-1368.

- 5. Shannak, R., Masa’deh, R., Al-Zu’bi, Z., Obeidat, B., Alshurideh, M. and Altamony, H. (2012) A Theoretical Perspective on the Relationship between Knowledge Management Systems, Customer Knowledge Management, and Firm Competitive Advantage. European Journal of Social Sciences, 32, 520-532.

- 6. Ismail, N. (2012) Organizational Commitment and Job Satisfaction among Staff of Higher Learning Education Institutions in Kelantan. Unpublished Master Thesis, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Sintok.

- 7. Tseng, S.-M. and Lee, P.-S. (2014) The Effect of Knowledge Management Capability and Dynamic Capability on Organizational Performance. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 27, 158-179.

https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-05-2012-0025 - 8. Hajir, J.A., Obeidat, B.Y., Al-dalahmeh, M.A. and Masa’deh, R. (2015) The Role of Knowledge Management Infrastructure in Enhancing Innovation at Mobile Telecommunication Companies in Jordan. European Journal of Social Sciences, 50, 313-330.

- 9. Obeidat, B., Al-Suradi, M., Masa’deh, R. and Tarhini, A. (2016) The Impact of Knowledge Management on Innovation: An Empirical Study on Jordanian Consultancy Firms. Management Research Review, 39, 1214-1238.

https://doi.org/10.1108/mrr-09-2015-0214 - 10. Yew, L.T. (2013) The Influence of Human Resources Management (HRM) Practices on Organizational Commitment and Turnover Intention of Academics in Malaysia: The Organizational Support Perspective. Proceedings of the International Conference on Business and Information, Bali, 7-9 July 2013.

- 11. Riveros, A.M. and Tsai, T.S.T. (2011) Career Commitment and Organizational Commitment in For-Profit and Non-Profit Sectors. International Journal of Emerging Science, 1, 324-340.

- 12. Jain, A.K., Giga, S.I. and Cooper, C.L. (2009) Employee Well-Being, Control and Organizational Commitment. Learning and Organizational Development Journal, 30, 256-273.

- 13. Fossey, E.M. and Harvey, C.A. (2010) Finding and Sustaining Employment: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis of Mental Health Consumer Views. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 77, 303-314.

https://doi.org/10.2182/cjot.2010.77.5.6 - 14. Srivastava, S. (2013) Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment Relationship: Effect of Personality Variables. Vision: The Journal of Business Perspective, 17, 159-167.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0972262912483529 - 15. Mgedezi, S., Toga, R. and Mjoli, T. (2014) Intrinsic Motivation and Job Involvement on Employee Retention: Case Study—A Selection of Eastern Cape Government Departments. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5, 2119-2126.

https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n20p2119 - 16. Nwibere, B.M. (2014) Interactive Relationship between Job Involvement, Job Satisfaction, Organizational Citizenship Behaviour, and Organizational Commitment in Nigerian Universities. International Journal of Management and Sustainability, 3, 321-340.

- 17. Albdour, A.A. and Altarawneh, I.I. (2014) Employee Engagement and Organizational Commitment; Evidence from Jordan. International Journal of Business, 19, 192-212.

- 18. Alkalha, Z., Al-Zu’bi, Z., Al-Dmour, H., Alshurideh, M. and Masa’deh, R. (2012) Investigating the Effects of Human Resource Policies on Organizational Performance: An Empirical Study on Commercial Banks Operating in Jordan. European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences, 51, 44-64.

- 19. Al-Majali, M.Y. and Sunna’a, H.J.S. (2013) Jordan Ahli Bank’s Commitment to Applying the Concept of Strategic Management Field Study. International Review of Management and Business Research, 2, 746-775.

- 20. AL-Rousan, M.A. (2014) The Relationship between the Management Information System and the Administrative Empowerment (A Field Study on the Jordanian Banking Sector). International Journal of Business, Humanities and Technology, 4, 121-129.

- 21. Melhem, Y. (2003) Employee-Customer-Relationships: An Investigation into the Impact of Customer-Contact Employees’ Capabilities on Customer Satisfaction in Jordan Banking Sector. Unpublished PhD Dissertation, University of Nottingham, Nottingham.

- 22. Al-Ma’ani, A.I. (2013) Factors Affecting the Organizational Loyalty of Workers in the Jordanian Commercial Banks. Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business, 4, 878-896.

- 23. Abdallah, A. and Phan, C.A. (2007) The Relationship between Just-in-Time Production and Human Resource Management, and Their Impact on Competitive Performance. Yokohama Business Review, 28, 27-57.

- 24. Seo, J.Y. (2013) Job Involvement of Part-Time Faculty: Exploring Associations with Distributive Justice, Underemployment, Work Status Congruence, and Empowerment. Unpublished PhD Dissertation, University of Iowa, Iowa.

- 25. Masa’deh, R., Obeidat, B., Zyod, D. and Gharaibeh, A. (2015) The Associations among Transformational Leadership, Transactional Leadership, Knowledge Sharing, Job Performance, and Firm Performance: A Theoretical Model. Journal of Social Sciences (COES and RJ-JSS), 4, 848-866.

- 26. Masa’deh, R., Obeidat, B. and Tarhini, A. (2016) A Jordanian Empirical Study of the Associations among Transformational Leadership, Transactional Leadership, Knowledge Sharing, Job Performance, and Firm Performance: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Journal of Management Development, 35, 681-705.

https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-09-2015-0134 - 27. Phan, A.C., Abdallah, A.B. and Matsui, Y. (2011) Quality Management Practices and Competitive Performance: Empirical Evidence from Japanese Manufacturing Companies. International Journal of Production Economics, 133, 518-529.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2011.01.024 - 28. Aladwan, K., Bhanugopan, R. and Fish, A. (2013) To What Extent the Arab Workers Committed to Their Organizations? International Journal of Commerce and Management, 23, 306-326.

https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCoMA-03-2012-0020 - 29. Vratskikh, I., Masa’deh, R., Al-Lozi, M. and Maqableh, M. (2016) The Impact of Emotional Intelligence on Job Performance via the Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction. International Journal of Business and Management, 11, 69-91.

https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v11n2p69 - 30. Awamleh, N. (1996) Organizational Commitment of Civil Service Managers in Jordan: A Field Study. Journal of Management Development, 15, 65-74.

https://doi.org/10.1108/02621719610117277 - 31. Shannak, R., Obeidat, B. and Masa’deh, R. (2012) Culture and the Implementation Process of Strategic Decisions in Jordan. Journal of Management Research, 4, 257-281.

https://doi.org/10.5296/jmr.v4i4.2160 - 32. Obeidat, B., Masa’deh, R. and Abdallah, A. (2014) The Relationships among Human Resource Management Practices, Organizational Commitment, and Knowledge Management Processes: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. International Journal of Business and Management, 9, 9-26.

https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v9n3p9 - 33. Khan, T.I., Jam, F.A., Akbar, A., Khan, M.B. and Hijazi, S.T. (2011) Job Involvement as Predictor of Employee Commitment: Evidence from Pakistan. International Journal of Business and Management, 6, 252-262.

- 34. Mathieu, J.E. and Farr, J.L. (1991) Further Evidence for the Discriminant Validity of Measures of Organizational Commitment, Job Involvement, and Job Satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 127-133.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.76.1.127 - 35. Mathieu, J.E. and Zajac, D. (1990) A Review and Meta-Analysis of the Antecedents, Correlates, and Consequences of Organizational Commitment. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 171-194.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.171 - 36. Hirschfeld, R.R. and Field, H.S. (2000) Work Centrality and Work Alienation: Distinct Aspects of a General Commitment to Work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21, 789-800.

https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1379(200011)21:7<789::AID-JOB59>3.0.CO;2-W - 37. Paullay, I., Alliger, G. and Stone-Romero, E. (1994) Construct Validation of Two Instruments Designed to Measure Job Involvement and Work Centrality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79, 224-228.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.79.2.224 - 38. Lodahl, T.M. and Kejner, M.M. (1965) The Definition and Measurement of Job Involvement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 49, 24-33.

https://doi.org/10.1037/h0021692 - 39. DeCarufel, A. and Schaan, J.L. (1990) The Impact of Compressed Work Weeks on Police Job Involvement. Canadian Police College, 14, 81-97.

- 40. Hogan, N., Lambert, E. and Griffin, M. (2013) Loyalty, Love, and Investments: The Impact of Job Outcomes on the Organizational Commitment of Correctional Staff. Criminal Justice and Behaviour, 40, 355-375.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854812469944 - 41. Abdallah, A.B., Phan, C.P. and Matsui, Y. (2016) Investigating the Effects of Managerial and Technological Innovations on Operational Performance and Customer Satisfaction of Manufacturing Companies. International Journal of Business Innovation and Research, 10, 153-183.

https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBIR.2016.074824 - 42. Chen, C.-C. and Chiu, S.-F. (2009) The Mediating Role of Job Involvement in the Relationship between Job Characteristics and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. The Journal of Social Psychology, 149, 474-494.

https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.149.4.474-494 - 43. Hackett, R.D., Lapierre, L.M. and Hausdorf, P.A. (2001) Understanding the Links between Work Commitment Constructs. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58, 392-413.

https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2000.1776 - 44. Brown, S.P., and Leigh, T.W. (1996) A New Look at Psychological Climate and Its Relationship to Job Involvement, Effort and Performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 358-368.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.358 - 45. Singh, A. and Gupta, B. (2015) Job Involvement, Organizational Commitment, Professional Commitment, and Team Commitment: A Study of Generational Diversity. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 22, 1192-1211.

https://doi.org/10.1108/bij-01-2014-0007 - 46. Rowden, R.W. and Conine Jr., C.T. (2005) The Impact of Workplace Learning on Job Satisfaction in Small US Commercial Banks. Journal of Workplace Learning, 17, 215-230.

https://doi.org/10.1108/13665620510597176 - 47. Locke, E.A. (1976) The Nature Causes and Causes of Job Satisfaction. In: Dunnette, M.C., Ed., Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Rand McNally, Chicago, 1279-1349.

- 48. Yücel, I. (2012) Examining the Relationships among Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment, and Turnover Intention: An Empirical Study. International Journal of Business and Management, 7, 44-58.

https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v7n20p44 - 49. McNabb, N.S. (2009) The Daily Floggings Will Continue until Morale Improves: An Examination of the Relationships among Organizational Justice, Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment and Intention to Turnover. Unpublished PHD Dissertation, University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma.

- 50. Spector, P.E. (1997) Job Satisfaction: Application, Assessment, Causes, and Consequences. Sage, Thousand Oaks.

- 51. Ostroff, C. (1992) The Relationship between Satisfaction, Attitudes, and Performance: An Organizational Level Analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, 963-974.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.77.6.963 - 52. Schneider, B. and Snyder, R.A. (1975) Some Relationship between Job Satisfaction and Organizational Climate. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60, 318-328.

https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076756 - 53. Robbins, S.P. (2005) Essentials of Organizational Behavior. 8th Edition, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River.

- 54. Armstrong, M. (2006) A Handbook of Human Resource Management Practice. 10th Edition, Kogan Page Publishing, London.

- 55. Weiss, D.J., Dawis, R.V., England, G.W. and Lofquist, L.H. (1967) Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire. University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

- 56. Dirani, K.M. (2009) Measuring the Learning Organization Culture, Organizational Commitment and Job Satisfaction in the Lebanese Banking Sector. Human Resource Development International, 12, 189-208.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13678860902764118 - 57. Feinstein, A.H. and Vondrasek, D. (2001) A Study of Relationships between Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment among Restaurant Employees. Journal of Hospitality, Tourism, and Leisure Science.

http://hotel.unlv.edu/pdf/jobSatisfaction.pdf - 58. Buitendach, J.H. and Rothmann, S. (2009) The Validation of the Minnesota Job Satisfaction Questionnaire in Selected Organizations in South Africa. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 7, 1-8.

- 59. Sullivan, S.E. and Arthur, M.B. (2006) The Evolution of the Boundaryless Career Concept: Examining Physical and Psychological Mobility. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69, 19-29.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.09.001 - 60. Becker, H.S. (1960) Notes on the Concept of Commitment. American Journal of Sociology, 66, 32-40.

https://doi.org/10.1086/222820 - 61. Porter, L.W., Steers, R.M., Mowday, R.T. and Boulian, P.V. (1974) Organizational Commitment, Job Satisfaction, and Turnover among Psychiatric Technicians. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59, 603-609.

https://doi.org/10.1037/h0037335 - 62. Klein, H.J., Molloy, J.C. and Cooper, J.T. (2009) Conceptual Foundations: Construct Definitions and Theoretical Representations of Workplace Commitments. In: Klein, H.J., Becker, T.E. and Meyer, J.P., Eds., Commitment in Organizations: Accumulated Wisdom and New Directions, Routledge/Taylor and Francis Group, Florence, 3-36.

- 63. Enache, M., Sallan, J.M., Simo, P. and Fernandez, V. (2013) Organizational Commitment within a Contemporary Career Context. International Journal of Manpower, 34, 880-898.

https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-07-2013-0174 - 64. Mowday, R.T., Porter, L.W. and Steers, R.M. (1982) Employee-Organization Linkages: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism and Turnover. Academic Press, New York.

- 65. Meyer, J.P. and Allen, N.J. (1991) A Three-Component Conceptualization of Organizational Commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1, 61-89.

https://doi.org/10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z - 66. Gunlu, E., Aksarayli, M. and Percin, N.S. (2010) Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment of Hotel Managers in Turkey. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 22, 693-717.

https://doi.org/10.1108/09596111011053819 - 67. Meyer, J.P. and Herscovitch, L. (2001) Commitment in the Workplace: Toward a General Model. Human Resource Management Review, 11, 299-326.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4822(00)00053-X - 68. Furtmueller, E., van Dick, R. and Wilderom, C.P.M. (2011) On the Illusion of Organizational Commitment among Finance Professionals. Team Performance Management, 17, 255-278.

https://doi.org/10.1108/13527591111159009 - 69. Meyer, J.P., Stanley, D.J., Herscovitch, L. and Topolnytsky, L. (2002) Affective, Continuance, and Normative Commitment to the Organization: A Meta-Analysis of Antecedents, Correlates, and Consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61, 20-52.

https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1842 - 70. Riketta, M. (2002) Attitudinal Organizational Commitment and Job Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 257-266.

https://doi.org/10.1002/job.141 - 71. Chen, M., Wang, Y.S. and Sun, V. (2012) Intellectual Capital and Organizational Commitment. Personnel Review, 41, 321-339.

https://doi.org/10.1108/00483481211212968 - 72. Tatlah, A., Ali, Z. and Saeed, M. (2011) Leadership Behavior and Organizational Commitment: An Empirical Study of Educational Professionals. International Journal of Academic Research, 3, 1293-1298.

- 73. Kwantes, C.T. (2009) Culture, Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment in India and the United States. Journal of Indian Business Research, 1, 196-212.

https://doi.org/10.1108/17554190911013265 - 74. Meyer, J.P. and Parfyonova, N.M. (2010) Normative Commitment in the Workplace: A Theoretical Analysis and Re-Conceptualization. Human Resources Management Review, 20, 283-294.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.09.001 - 75. Davenport, J. (2010) Leadership Style and Organizational Commitment: The Moderating Effect of Locus of Control. Proceedings of ASBBS, Vol. 17, Las Vegas, 18-21 February 2010.

- 76. Cho, V. and Huang, X. (2012) Professional Commitment, Organizational Commitment, and the Intention to Leave for Professional Advancement. Information Technology and People, 25, 31-54.

https://doi.org/10.1108/09593841211204335 - 77. Kanungo, R.N. (1979) The Concept of Alienation and Involvement Revisited. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 119-138.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.86.1.119 - 78. Cohen, A. (1999) Relationships among Five Forms of Commitment: An Empirical Assessment. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20, 285-308.

https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199905)20:3<285::AID-JOB887>3.0.CO;2-R - 79. McElroy, J.C., Morrow, P.C. and Wardlow, T.R. (1999) A Career Stage Analysis of Police Officer Work Commitment. Journal of Criminal Justice, 27, 507-516.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2352(99)00021-5 - 80. Yiing, L.H. and Bin Ahmad, K.Z. (2009) The Moderating Effects of Organizational Culture on the Relationships between Leadership Behaviour and Organizational Commitment and between Organizational Commitment and Job Satisfaction and Performance. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 30, 53-86.

https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730910927106 - 81. Kuo, Y. (2013) Organizational Commitment in an Intense Competition Environment. Industrial Management and Data Systems, 113, 39-56.

https://doi.org/10.1108/02635571311289656 - 82. Islam, T., Khan, S.R., Ahmad, N.U.B., Ali, G., Ahmed, I. and Bowra, Z.A. (2013) Turnover Intentions: The Influence of Perceived Organizational Support and Organizational Commitment. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 103, 1238-1242.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.10.452 - 83. Blau, G. and Boal, K. (1987) Conceptualizing How Job Involvement and Organizational Commitment Affect Turnover and Absenteeism. Academy of Management Review, 12, 288-300.

- 84. Suifan, T.S., Abdallah, A.B. and Sweis, R.J. (2015) The Effect of a Manager’s Emotional Intelligence on Employees’ Work Outcomes in the Insurance Industry in Jordan. International Business Research, 8, 67-82.

- 85. Uygur, A. and Kilic, G. (2009) A Study into Organizational Commitment and Job Involvement: An Application towards the Personnel in the Central Organization for Ministry of Health in Turkey. Ozean Journal of Applied Sciences, 2, 113-125.

- 86. Gunz, H.P. and Gunz, S.P. (1994) Professional/Organizational Commitment and Job Satisfaction for Employed Lawyers. Human Relations, 47, 801-828.

https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679404700703 - 87. Parasuraman, S. and Nachman, S.A. (1987) Correlates of Organizational and Professional Commitment: The Case of Musicians in Symphony Orchestras. Group and Organization Management, 12, 287-303.

https://doi.org/10.1177/105960118701200305 - 88. Lachman, R. and Aranya, N. (1986) Job Attitudes and Turnover Intention among Professionals in Different Work Settings. Organization Studies, 7, 279-293.

https://doi.org/10.1177/017084068600700305 - 89. Hartmann, L.C. and Bambacas, M. (2000) Organizational Commitment: A Multi Method Scale Analysis and Test of Effects. The International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 8, 89-108.

https://doi.org/10.1108/eb028912 - 90. Tayyeb, S. and Riaz, N. (2004) Validation of the Three-Component Model of Organizational Commitment in Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 19, 123-149.

- 91. Singh, M. and Pestonjee, M. (1990) Job Involvement, Sense of Participation and Job Satisfaction: A Study in Banking Industry. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 26, 159-165.

- 92. Kanungo, R.N. (1982) Measurement of Job and Work Involvement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67, 341-349.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.67.3.341 - 93. Pfeffer, J. (1994) Competitive Advantage through People. Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

- 94. Diefendorff, J., Brown, D., Kamin, A. and Lord, B. (2002) Examining the Roles of Job Involvement and Work Centrality in Predicting Organizational Citizenship Behaviors and Job Performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 93-108.

https://doi.org/10.1002/job.123 - 95. Wood, S., Van Veldhoven, M., Croom, M. and de Menezes, L.M. (2012) Enriched Job Design, High Involvement Management and Organizational Performance: The Mediating Roles of Job Satisfaction and Well-Being. Human Relations, 65, 419-445.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726711432476 - 96. Wood, S. and de Menezes, L.M. (2011) High Involvement Management, High Performance Work Systems and Well-Being. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22, 1586-1610.

- 97. Ollo-López, A., Bayo-Moriones, A. and Larraza-Kintana. M. (2016) Disentangling the Relationship between High-Involvement-Work-Systems and Job Satisfaction. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 38, 620-642.

https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-04-2015-0071 - 98. Hennessey, B.A. and Amabile, T.M. (2010) Creativity. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 569-598.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100416 - 99. Suliman, A. and Al Kathairi, M. (2012) Organizational Justice, Commitment and Performance in Developing Countries: The Case of the UAE. Employee Relations, 35, 98-115.

https://doi.org/10.1108/01425451311279438 - 100. Al Azmi, N., Al-Lozi, M., Zu’bi, Z., Dahiyat, S. and Masa’deh, R. (2012) Patients Attitudes toward Service Quality and Its Impact on Their Satisfaction in Physical Therapy in KSA Hospitals. European Journal of Social Sciences, 34, 300-314.

- 101. Mohammed, F. and Eleswed, M. (2013) Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment: A Correlational Study in Bahrain. International Journal of Business, Humanities and Technology, 3, 43-53.

- 102. Kanwar, Y.P.S., Singh, A.K. and Kodwani, A.D. (2012) A Study of Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment and Turnover Intent among the IT and ITES Sector Employees. The Journal of Business Perspective, 16, 27-35.

https://doi.org/10.1177/097226291201600103 - 103. Anari, N.N. (2012) Teachers: Emotional Intelligence, Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment. Journal of Workplace Learning, 24, 256-269.

https://doi.org/10.1108/13665621211223379 - 104. Al-Hussami, M., Saleh, M.Y., Abdalkader, R.H. and Mahadeen, A.I. (2011) Predictors of Nursing Faculty Members’ Organizational Commitment in Governmental Universities. Journal of Nursing Management, 19, 556-566.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01148.x - 105. Al-Aameri, A.S. (2000) Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment for Nurses. Saudi Medical Journal, 21, 531-535.

- 106. Tiwari, V. and Singh, S.K. (2014) Moderation Effect of Job Involvement on the Relationship between Organizational Commitment and Job Satisfaction. SAGE Open, 1-7.

- 107. Eskildsen, J.K., Westlund, A.H. and Kristensen, K. (2004) Measuring Employee Assets—The Nordic Employee Index. Business Process Management Journal, 10, 537-550.

https://doi.org/10.1108/14637150410559216 - 108. Suifan, T., Abdallah, A.B. and Diab, H. (2016) The Influence of Work Life Balance on Turnover Intention in Private Hospitals: The Mediating Role of Work Life Conflict. European Journal of Business and Management, 8, 126-139.

- 109. Association of Banks in Jordan (2014) Annual Report.

http://www.abj.org.jo/en-us/annualreports.aspx - 110. Sekaran, U. and Bougie, R. (2013) Research Methods for Business—A Skill Building Approach. 6th Edition, John Wiley and Sons, West Sussex.

- 111. Abdallah, A.B., Obeidat, B.Y. and Aqqad, N.O. (2014) The Impact of Supply Chain Management Practices on Supply Chain Performance in Jordan: The Moderating Effect of Competitive Intensity. International Business Research, 7, 13-27.

https://doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v7n3p13 - 112. Abdallah, A.B. (2013) The Influence of “Soft” and “Hard” Total Quality Management (TQM) Practices on Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) in Jordanian Manufacturing Companies. International Journal of Business and Management, 8, 1-13.

https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v8n21p1 - 113. Meyer, J.P. and Allen, N.J. (1991) A Three-Component Conceptualization of Organizational Commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1, 61-89.

https://doi.org/10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z - 114. Armstrong, J.S. and Overton, T.S. (1977) Estimating Nonresponse Bias in Mail Surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14, 396-402.

https://doi.org/10.2307/3150783 - 115. Harman, H.H. (1976) Modern Factor Analysis. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- 116. Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B. and Anderson, R. (2010) Multivariate Data Analysis. Prentice Hall, Inc., Upper Saddle River.

- 117. Bollen, K.A. (1989) Structural Equations with Latent Variables. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York.

https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118619179 - 118. Garver, M.S. and Mentzer, J.T. (1999) Logistics Research Methods: Employing Structural Equation Modelling to Test for Construct Validity. Journal of Business Logistics, 20, 33-57.

- 119. Hu, L. and Bentler, P.M. (1999) Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1-55.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118 - 120. Anderson, J.C. and Gerbing, D.W. (1988) Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411-423.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411 - 121. Fornell, C. and Larcker, D.F. (1981) Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39-50.

https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312 - 122. Baron, R. and Kenny, D. (1986) The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173-1182.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 - 123. Hayes, A. (2009) Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical Mediation Analysis in the New Millennium. Communication Monographs, 76, 408-420.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750903310360 - 124. Hayes, A.F. (2013) Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. The Guilford Press, New York.

- 125. Ramadan, B., Dahiyat, S., Bontis, N. and Al-dalahmeh, M. (2017) Intellectual Capital, Knowledge Management and Social Capital within the ICT Sector in Jordan. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 18. (Accepted and to be published)

- 126. Abdallah, A. and Matsui, Y. (2009) The Impact of Lean Practices on Mass Customization and Competitive Performance of Mass-Customizing Plants. Proceedings of the 20th Annual Production and Operations Management Society (POMS) Conference, Orlando, 1-4 May 2009.

- 127. Kanaan, R., Masa’deh, R. and Gharaibeh, A. (2013) The Impact of Knowledge Sharing Enablers on Knowledge Sharing Capability: An Empirical Study on Jordanian Telecommunication Firms. European Scientific Journal, 9, 237-258.

- 128. Masa’deh, R., Almajali, D., Obeidat, B., Aqqad, N. and Tarhini, A. (2016) The Role of Knowledge Management Infrastructure in Enhancing Job Satisfaction. International Journal of Public Administration, 39, 14-34.

- 129. Chew, J. and Chan, C. (2008) Human Resource Practices, Organizational Commitment and Intention to Stay. International Journal of Manpower, 29, 503-522.

https://doi.org/10.1108/01437720810904194 - 130. Zu’bi, Z., Al-Lozi, M., Dahiyat, S., Alshurideh, M. and Al Majali, A. (2012) Examining the Effects of Quality Management Practices on Product Variety. European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences, 51, 123-139.

- 131. Obeidat, B., Sweis, R., Zyod, D., Masa’deh, R. and Alshurideh, M. (2012) The Effect of Perceived Service Quality on Customer Loyalty in Internet Service Providers in Jordan. Journal of Management Research, 4, 224-242.

https://doi.org/10.5296/jmr.v4i4.2130 - 132. Masa’deh, R., Shannak, R., Maqableh, M. and Tarhini, A. (2016) The Impact of Knowledge Management on Job Performance in Higher Education: The Case of the University of Jordan. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 29, 25-43.

- 133. Abdallah, A.B. and Matsui, Y. (2007) The Relationship between JIT Production and Manufacturing Strategy and Their Impact on JIT Performance. Proceedings of the 18th Annual Production and Operations Management Society (POMS) Conference, Dallas.