World Journal of Mechanics

Vol.06 No.11(2016), Article ID:71937,15 pages

10.4236/wjm.2016.611031

Higgs-Like Mechanism by Confinement of Quarks in a Chemical Non-Equilibrium Model

Leif Matsson

Department of Physics, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: August 30, 2016; Accepted: November 8, 2016; Published: November 11, 2016

ABSTRACT

A chemical non-equilibrium equation for binding of massless quarks to antiquarks, combined with the spatial correlations occurring in the condensation process, yields a density dependent form of the double-well potential in the electroweak theory. The Higgs boson acquires mass, valence quarks emerge and antiparticles become suppressed when the system relaxes and symmetry breaks down. The hitherto unknown dimensionless coupling parameter to the superconductor-like potential becomes a re- gulator of the quark-antiquark asymmetry. Only a small amount of quarks become “visible”―the valence quarks, which are 13% of the total sum of all quarks and antiquarks―suggesting that the quarks-antiquark pair components of the becoming quark- antiquark sea play the role of dark matter. When quark-masses are in-weighted, this number approaches the observed ratio between ordinary matter and the sum of ordinary and dark matter. The model also provides a chemical non-equilibrium explanation for the information loss in black holes, such as of baryon number.

Keywords:

Confinement of Quarks, Higgs Mechanism, Emergence of Mass, Dark Matter, Valence Quarks, Antiquark Suppression, Black Holes, Dark Energy

1. Introduction

Two ways for explaining the origin of mass, QCD and confinement of quarks and the Higgs-mechanism in the electroweak (EW) theory have been discussed by Wilczek: “Superficially those mechanisms appear quite different, but at a fundamental level they are essentially the same” [1] . Such a relationship is derived here in a chemical non- equilibrium model for binding massless quarks to their respective antiquarks. The model yields the same type of superconductor-like potential that generates mass in the EW theory, however the earlier unknown dimensionless coupling to the potential becomes a regulator of the quark-antiquark asymmetry. Only a fraction of the quarks, 13% of the total sum of all once free quarks and antiquarks, become “visible” as valence quarks, suggesting that excited pairs of the “invisible” non-valence quarks and the “invisible” antiquarks could play the role of dark matter in a remote quasi-free state. The model also provides an explanation as to how valence quarks emerge by suppression of antiquarks.

The Sakharov constraints [2] ―violation of C and CP symmetry and baryon number conservation, in a thermodynamic non-equilibrium Universe which still expands from a super-dense state―are partly relevant also for these studies. However, to create a pro- ton or neutron, with massive valence quarks and a spatially correlated quark-antiquark sea from a gas-like state of equal densities of free massless quarks (q) and antiquarks , the gas must also condense and the number (density) of quarks must increase relative to the number (density) of antiquarks. This implies that the binding of quarks to antiquarks takes place at chemical non-equilibrium conditions. In combination with strong spatial correlations that emerge in the condensation process, such conditions― an increasing density of quark-antiquark

, the gas must also condense and the number (density) of quarks must increase relative to the number (density) of antiquarks. This implies that the binding of quarks to antiquarks takes place at chemical non-equilibrium conditions. In combination with strong spatial correlations that emerge in the condensation process, such conditions― an increasing density of quark-antiquark  -pairs (ψ) and a density of quarks (becoming valence quarks) that increases relative to that of antiquarks―are very unfortunate, because the grand canonical ensemble then admits only fluctuations (fugacity) about a constant number of particles [3] . The problem therefore also goes beyond lattice QCD, which relies on the grand canonical ensemble and more “thermotropic” type conditions [4] .

-pairs (ψ) and a density of quarks (becoming valence quarks) that increases relative to that of antiquarks―are very unfortunate, because the grand canonical ensemble then admits only fluctuations (fugacity) about a constant number of particles [3] . The problem therefore also goes beyond lattice QCD, which relies on the grand canonical ensemble and more “thermotropic” type conditions [4] .

Quark-gluon interaction is strong at distances of about a nucleon diameter (10−15 m), but weakens at high energies (temperatures) where quarks interact at shorter distances. Already at about 150 MeV (~2 × 1012 degrees K), nuclear matter boils down to a quark- gluon plasma (QGP) [4] , which behaves like a fluid with small shear viscosity (short mean free path) and a very high opaqueness towards color, not unlike electromagnetic Debye screening in a usual plasma. At infinite energy, quarks become asymptotically free [5] [6] and attain the same density as antiquarks. Conversely, when nuclear matter cools down and condenses, the couplings and spatial correlations between quarks and antiquarks become strong and a surplus of valence quarks emerge. Neither transport theory can solve this chemical non-equilibrium problem [4] . Apart from that, QCD also has a complicated singular infrared behavior [7] [8] that flaws calculations of bound states.

This paper identifies and suggests solutions to some of these problems that underlie the standard model. Section 2 describes the chemical non-equilibrium equation for binding of quarks (fermions) to antiquarks (antifermions). The binding equation, combined with a coherent (local) formulation of the strong spatial (non-local) correlations between the condensing particles, as shown in Section 3, yields the Ginsburg-Landau (GL) like potential used in EW theory, however, with a density-dependent order parameter. Section 4 provides an explanation as to how mass, dark matter, and valence quarks emerge by suppression of antiquarks. It is shown that the coupling to the GL- like potential becomes a regulator of the  -asymmetry, leaving only valence quarks, which are about 13% of the total sum of all quarks and antiquarks, “observable”. When the different effective quark-masses are in-weighted, this value approaches the observed ratio between ordinary and dark matter. Section 5 discusses possible implications of this density-dependent model for general relativity (GR), black holes, gravitational waves, and expansion and inflation of the Universe.

-asymmetry, leaving only valence quarks, which are about 13% of the total sum of all quarks and antiquarks, “observable”. When the different effective quark-masses are in-weighted, this value approaches the observed ratio between ordinary and dark matter. Section 5 discusses possible implications of this density-dependent model for general relativity (GR), black holes, gravitational waves, and expansion and inflation of the Universe.

2. Nonequilibrium Quark-Antiquark Binding

The chemical non-equilibrium conditions exclude usual quantum field theory methods, such as the Bethe-Salpeter equation and eikonal type models [9] [10] , to describe the binding of quarks or leptons to their respective antiparticles. Instead, the model is founded on three dynamical constraints: 1) an equation for chemical non-equilibrium binding of massless quarks to massless antiquarks, 2) the initial boundary constraints for the quark and antiquark scalar field amplitudes q and , which are assumed equal for left- and right-handed fermions, and 3) the strong spatial correlations between the

, which are assumed equal for left- and right-handed fermions, and 3) the strong spatial correlations between the  -pairs. These field amplitudes, which measure the non-equilibrium deviations from the usual chemical equilibrium type quantum fields, are linearly proportional to the respective particle numbers and can hence be treated as “densities”as long as the particles are massless and unobservable.

-pairs. These field amplitudes, which measure the non-equilibrium deviations from the usual chemical equilibrium type quantum fields, are linearly proportional to the respective particle numbers and can hence be treated as “densities”as long as the particles are massless and unobservable.

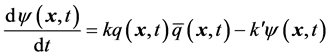

The rate-equation for chemical non-equilibrium binding of massless quarks to antiquarks when the system cools down, is given by

, (1)

, (1)

k and  being the binding and unbinding constants. Spinors are not needed, because quarks (fermions) can bind to antiquarks (antifermions) only when the particles are approximately at rest relative to each other and then exchange only soft quanta. Equation (1) thus corresponds to a form of coherent approximation. Recall that the aim is not to describe relativistic scattering of differently handed chiral fermions, but just the increase in the numbers (densities) of bound

being the binding and unbinding constants. Spinors are not needed, because quarks (fermions) can bind to antiquarks (antifermions) only when the particles are approximately at rest relative to each other and then exchange only soft quanta. Equation (1) thus corresponds to a form of coherent approximation. Recall that the aim is not to describe relativistic scattering of differently handed chiral fermions, but just the increase in the numbers (densities) of bound  -states and valence quarks. This does not exclude that k and k’ may depend on scattering effects. Observe also that Equation (1) goes in both directions―to the right when the system cools down and to the left when the temperature (energy) increases―and should hence be suitable to describe hadronization-fragmentation processes.

-states and valence quarks. This does not exclude that k and k’ may depend on scattering effects. Observe also that Equation (1) goes in both directions―to the right when the system cools down and to the left when the temperature (energy) increases―and should hence be suitable to describe hadronization-fragmentation processes.

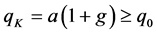

Equation (1) also obeys the initial boundary constraints

, (2)

, (2)

and that the initial “free” quark and antiquark amplitudes, q0 and , should be equal in magnitude at the big bang, in extremely high-energy proton-proton collisions, and supposedly also in the central region of black holes.

, should be equal in magnitude at the big bang, in extremely high-energy proton-proton collisions, and supposedly also in the central region of black holes.

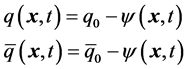

After insertion of these constraints, Equation (1) reads

(3a)

(3a)

, (3b)

, (3b)

where ,

,  , and

, and .

.

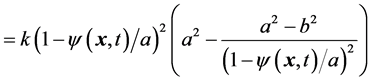

The solution to Equation (3) is

(4)

(4)

where the “short-hand” notations  and

and  are the screening and screened initial quark and antiquark field amplitudes, and

are the screening and screened initial quark and antiquark field amplitudes, and

To quantify the screening effect and study the emergence of valence quarks, mass and dark matter by suppression of antimatter when the system cools down, however, Equation (3) must be first combined with the spatial correlations between the

However, to make the emerging particles point-like, Equation (5) must be contracted and synchronized to a fictitious “centre of mass”,

After a certain time,

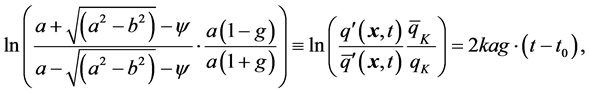

which can be combined with Equation (3). Equation (6), which has the form of a Bose- Einstein distribution, also corresponds formally to the grand partition function, with

To obtain the relaxation dynamics and time evolution of the correlated system, Equation (6) must be linked to Equation (3). The time derivative of Equation (6),

combined with Equation (3) then yields

which has the solutions

To create a baryon with a small finite number (one or two) of valence quarks (Figure 1(c)) of a certain flavour, and a sea of

Figure 1. At infinite energy, couplings and correlations between quarks and antiquarks vanish, and the brackets disappear. All three systems then contain alternating sequences with equal amounts of free quarks and antiquarks, and the two infinite systems (b) and (c) become identical. Depending on how this infinite system cools down, i.e. how quarks and antiquarks become correlated, a valence quark qB with nonzero baryon number B = 1/3: (c) may, or (b) may not be frozen out. This is beyond the grand canonical ensemble, which only allows fluctuations about a constant number of quarks. However, regardless of whether the system is finite or infinite, all antiquarks become bound by quarks and condensed into a quark-antiquark sea. The reversed process provides an explanation as to how quantum numbers like B are lost, such as in black holes.

bound

By the topological quantization, the stationary zero order term of unstable

3. Derivation of a GL-Like Potential

By the contraction of all (x, t) to a fictitious “centre of mass” (x, t)―an approximation needed to derive the dynamics and to make all particles point-like―the internal structure and dynamics of the system were neglected. However, in principle, Equation (5)

Figure 2. The gradual emergence of mass,

could correspond to any arbitrary structure and dynamics.

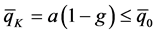

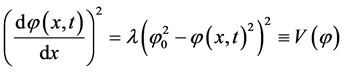

For simplicity the time dependent solution in Equation (9) is interpreted as a travelling wave on a string-like 1D lattice of

hence

This V(φ), which corresponds to a continuum approximation dynamics [15] of the discrete “lattice” in Equation (5), now equals the GL-like potential of the scalar field component that remains non-zero in the unitary gauge of the EW model, and λ = g2 as the hitherto unknown dimensionless parameter [16] . However, in this collective model, V(φ) is the density-dependent, hence lyotropic [17] , potential energy of the chemical non-equilibrium system of quarks and antiquarks (Figure 2(c)), and leptons and antileptons, and λ = g2 has become a regulator of the antiparticle suppression as will be further explained below.

The derivative of Equation (11) yields the spatial part of the equation of motion

albeit for a particle with imaginary mass. This flaw too is restored by the displacement

and the corresponding equation of motion reads

The mass term

However, the corresponding field displacement caused by the relaxation and condensation of the actual many-body system, does not take place until after all quarks except for a small number of valence quarks (Figure 1(c)), have been pairwise stably bound to antiquarks.

4. Quark-Antiquark Asymmetry

This chemical non-equilibrium model yields a quark-antiquark asymmetry,

This determines in turn the dimensionless parameter which now yields the

The topological quantization,

Since quarks are initially free and massless, at infinite energies essentially only photons contribute to the infinite energies to the initial binding of quarks by antiquarks and to the induction of mass, and gluons contribute later at finite energies. The number of valence quarks Qf ≤ 2, with flavour f and mass mf, is related to the number Np of

These model derivations, which should hold for each separate flavour, also hold for charged leptons, which contribute similarly to the ratio between ordinary and dark matter. For instance, a condensate of massless electrons and positrons can produce para-positronium spin-zero atoms with a lifetime τp that decreases from infinity to 2ħ/(mec2α5)~1.25 × 10−10 s when the electron mass me increases from zero to 511 keV, α being the fine structure constant. Since τp is about 1012 times longer than the lifetime of a Higgs boson, τH = 1.56 × 10−22 s, such a lepton condensate can thus also contribute to the GL-like potential and to the Higgs boson. Leptons probably contribute much less than baryons to the total mass of the Universe [1] , however, this is also a question of abundance, such as of neutrinos and maybe other weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs).

The actual model can also explain the binding of massless neutrinos (nK) to massless anti-neutrinos (

A softly bound condensate of up and down

To derive

The dark mass candidates available in this model are thus identified as the

If quarks and antiquarks in the stationary state can acquire mass before symmetry breakdown, their masses should have opposite signs and their gravitational contributions, one attractive and one repulsive, should cancel if quarks and antiquarks are not too far separated. However, at larger separations, such a repulsive form of gravitation could eventually drive the expansion of the universe. The same reasoning should hold for leptons.

5. Summary and Conclusions

A density-dependent, hence lyotropic [17] , form of the double-well potential employed in EW theory has been derived from a chemical non-equilibrium dynamics that describes the confinement of quarks. The model, which is a mean-field theory, shows that the Higgs mechanism and the confinement of quarks are essentially the same [1] . This relationship obtains by combining three different keys: Equation (1), the chemical non-equilibrium binding of quarks to antiquarks, Equation (2), the initial boundary constraints for these two reactants, and Equation (6), the strong spatial correlations between quark-antiquark pairs that emerge when the system cools down. One also had to redefine the initial quark field amplitudes, q0 and

It is still not possible to predict the mass

This chemical non-equilibrium type of dynamics is assumed to have controlled the relaxation dynamics after big bang when baryonic matter with a “surplus” of valence quarks was frozen out from a hot gaseous Universe with equal amounts of massless quarks and antiquarks. It is assumed to also control the relaxation after high-energy proton-proton collisions, and probably also essential parts of the dynamics in black holes.

Obviously, it would have been preferable to obtain the binding of quarks to antiquarks by exchange of gauge particles in 4D. However, the emergence of valence quarks―an increasing number of quarks relative to the number of antiquarks―implies chemical non-equilibrium conditions. In combination with strong spatial correlations, here represented by Equation (6), that emerge when quarks condense via a plasma phase [4] into point-like particles, the chemical non-equilibrium becomes a crucial statistical mechanical problem [3] beyond reach for the grand canonical ensemble which allows, at most, fluctuations about a constant number of particles, and hence beyond lattice QCD. Such non-equilibrium conditions also go beyond transport theories and string models, and a Bethe-Salpeter calculation of the binding mechanism in QCD would become too complicated even at equilibrium conditions. Unable to obtain the quark-antiquark binding by exchange of photons and gluons, the actual two-steps approach to the questions of emergence of mass, dark matter, and valence quarks, thus seems to be the best option at this stage; first the density-dependent GL-like potential is derived, by combing Equation (3) with Equation (6), and then this potential is inserted into the EW theory.

The Nielsen-Olesen (NO) string [23] can perhaps illustrate how the abelian part of the EW theory would behave with variable field amplitudes. The cosmic NO-type string would then as usual be defined by two coaxial core cylinders, one with a radius equal to the penetration depth λ = 1/mZ of the gauge vector field A, and one with a radius equal to the coherence length ξ = 1/mH, the inverse of the Higgs boson mass (Figure 3).

The inverse mass mZ of the Z-boson plays the role of penetration length in this density-dependent superconductor-like model [24] . However, the penetration depth and the coherence length are here regulated by the lyotropic conditions,

Spontaneous symmetry breaking occurs in many condensed matter systems such as superconductors, ferromagnets and crystals. In the actual chemical non-equilibrium den- sity-dependent [17] liquid crystal-like system, mass and valence quarks (baryons) emerge

Figure 3. An illustration of how the coherence length

as topological defects [14] (hence no ether) in an otherwise empty space, except for electro-magnetism and gravitation. Unstably bound particles and antiparticles, such as those in the stationary state, exist only in and about excited hot areas in space. The model works equally well driven backward by Equation (1), suggesting that it could also simulate the excitatory dynamics in black holes when the mass-energy density increases infinitely towards the central singular region, leading to creation of pairs of dust-like particles, which finally become massless in a dynamics with restored symmetry (Figure 2(c)). However, if antiparticles acquire a negative mass, as suggested before, this should imply a repulsive form of gravitation alongside with the normal attractive one. This could reduce the infinite increase of gravitation and singular behaviour of GR in the central region of black holes. At longer distances, such a negative gravitation could perhaps also drive the observed expansion of the Universe attributed to the cosmological constant (dark energy) in GR.

Given that 4.9% of all mass is visible (mv), the actual model yields 25.9% dark mass (md), which leaves 69.2% dark energy (ed). The model thus gives the correct order of magnitude for the ratio between visible and non-visible mass. However, since both the visible and the dark masses started from zero at the big bang, this model should comply better with inflation than an exploding Universe containing massive objects from start. The actual model suggests that the dark energy equals the kinetic energy of the dark mass. This energy, which was neglected together with the structure in Equation (6), is estimated to

Similar to the “atomistic” theory of matter and electricity proposed by Einstein and Rosen [26] , this model reduces the warping of space-time implied by the Schwarzschild metric factor (1 - 2GM/rc2), but in a different manner. When energy increases, the chemical non-equilibrium model dynamics goes backwards. M then becomes replaced by

When mass vanishes, the dust-like particles accelerate to the velocity of light and their clocks stop ticking, at least until they become rematerialized. The question is whether the negative gravitation and negative energy are sufficient to permit rematerialized particles to return to our own world sheet from the interior of black holes [26] . The existence of relativistic jets seems to support such a possibility, but it is also a question whether these jets are driven by the accretion disk [28] [29] , or by the black hole itself. However, it is doubtful that tidal forces outside or at the event horizon can drive Equation (1) backward and trigger pair-creation.

Clearly, this chemical non-equilibrium interaction is but an attempt to model what actually takes place in the real Universe, however, it seems to be first to go beyond the grand canonical ensemble in a system containing strong spatial correlations, and it also seems to work reasonably well. Observe that transport theories have not succeeded to solve this type of chemical non-equilibrium problem, and have thus not solved the problem for lattice QCD [4] . The actual model, which starts with massless particles, also provides a novel aspect on the mysterious wave-particle duality. After symmetry breakdown, both minima of the double-well potential―one corresponding to the de Broglie/Schrödinger wave nature of electrons without mass and one corresponding to electrons with mass (Figure 2(d))―have become equally physically probable. Hence, since the massless wave, which coexists with the corresponding massive particle, allows non-local interactions by infinite wavelength quanta, which are in principle non-loca- lizable, this might resolve some of the worst controversies between quantum mechanics and relativity, such as signals propagating faster than light.

It is also interesting to compare the

Acknowledgements

I thank Ludvig Faddeev for stimulating discussions on this matter many years ago at CERN, where I first got the idea for the model.

Cite this paper

Matsson, L. (2016) Higgs-Like Mechanism by Confinement of Quarks in a Chemical Non-Equilibrium Mo- del. World Journal of Mechanics, 6, 441-455. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/wjm.2016.611031

References

- 1. Wilczek, F. (2012) Origins of Mass. Central European Journal of Physics, 10, 1021-1037.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/s11534-012-0121-0 - 2. Sakharov, A. (1967) Violation of CP Invariance, C Asymmetry, and Baryon Asymmetry of the Universe. JETP Letters, 5, 24-27.

- 3. Reichl, L.E. (1998) A Modern Course in Statistical Physics. 2nd Edition, John Wiley & Sons, New York.

- 4. Jacak, B.V. and Müller, B. (2012) The Exploration of Hot Nuclear Matter. Science, 337, 310-314.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1215901 - 5. Gross, D.J. and Wilczek, F. (1973) Ultraviolet Behavior of Non-Abelian Gauge Theories. Physical Review Letters, 30, 1343-1346.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.30.1343 - 6. Politzer, D.H. (1973) Reliable Perturbative Results for Strong Interactions? Physical Review Letters, 30, 1346-1349.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.30.1346 - 7. Gross, D.J., Pisarski, R.D. and Yaffe, L.G. (1981) QCD and Instantons at Finite Temperature. Reviews of Modern Physics, 53, 43-80.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.53.43 - 8. Matsson, L. and Meuldermans, R. (1977) Long Range Correlations in Forward Quark-(Anti-) Quark Scattering in QCD. Physics Letters B, 70, 309-312.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(77)90665-7 - 9. Brezin, E., Itzykson, C. and Zinn-Justin, J. (1970) Relativistic Balmer Formula Including Recoil Effects. Physical Review D, 1, 2349-2355.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.1.2349 - 10. Lévy, M. and Sucher, J. (1970) Asymptotic Behavior of Scattering Amplitudes in the Relativistic Eikonal Approximation. Physical Review D, 2, 1716-1724.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.2.1716 - 11. Doi, M. and Edwards, S.F. (1986) The Theory of Polymer Dynamics. 3rd Edition, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- 12. Debye, P. (1946) The Intrinsic Viscocity of Polymer Solutions. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 14, 636-639.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.1724075 - 13. Flory, P.J. (1989) Statistical Mechanics of Chain Molecules. 2nd Edition, Hanser Publishers, Munich.

- 14. Jackiw, R. (1977) Quantum Meaning of Classical Field Theory. Reviews of Modern Physics, 49, 681-706.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.49.681 - 15. Combs, A.J. and Yip, S. (1983) Single-Kink Dynamics in a One-Dimensional Atomic Chain. A Nonlinear Atomistic Theory and Numerical Simulation. Physical Review B, 28, 6873-6885.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.28.6873 - 16. Huang, K. (1992) Quarks, Leptons & Gauge Fields. 2nd Edition, World Scientific, Singapore.

- 17. De Gennes, P.G. and Prost, J. (1993) The Physics of Liquid Crystals. 2nd Edition, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- 18. Ade, P.A.R., Aghanim, N., Arnaud, M., et al. (2015) Planck 2015 Results. XIII. Cosmological Parameters. arXiv:1502.01589

- 19. Chalmers, M. (2015) Forsaken Pentaquark Particle Spotted at CERN. Nature, 523, 267-268.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature.2015.17968 - 20. Cho, A. (2016) The Social Life of Quarks. Science, 351, 217-219.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.351.6270.217 - 21. Kajita, T. (1999) Atmospheric Neutrino Results from Super-Kamiokande and Kamiokande —Evidence for Vμ Oscillations. Nuclear Physics B-Proceedings Supplements, 77, 123-132.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0920-5632(99)00407-7 - 22. Ahmad, Q.R., McCauley, N., McDonald, A.B., McDonald, D.S., et al. (2001) Measurement of the Rate of Ve + d → p + p + e- Interactions Produced by 8B Solar Neutrinos at the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory. Physical Review Letters, 87, Article ID: 071301.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.071301 - 23. Nielsen, H.B. and Olesen, P. (1973) Vortex-Line Models for Dual Strings. Nuclear Physics B, 61, 45-61.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0550-3213(73)90350-7 - 24. Volovik, G.E. (2012) The Universe in a Helium Droplet. 3rd Edition, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- 25. Plümer, M., Raha, S. and Weiner, R.M. (1984) Effects on Confinement on the Sound Velocity in a Quark-Gluon Plasma. Physics Letters B, 139, 198-202.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(84)91244-9 - 26. Einstein, A. and Rosen, N. (1935) The Particle Problem in the General Theory of Relativity. Physical Review, 48, 73-77.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.48.73 - 27. Abbot, B.P., et al. (2016) Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger. Physical Review Letters, 116, Article ID: 061102.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.061102 - 28. Bower, G.C. (2016) The Screams of a Star Being Ripped Apart. Science, 351, 30-31.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.aad5541 - 29. van Velzen, S., Anderson, G.E., Stone, N.C., et al. (2016) A Radio Jet from the Optical and X-Ray Bright Stellar Tidal Disruption Flare ASASSN-14li, Science, 351, 62-65.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.aad1182 - 30. Dirac, P.A.M. (1930) A Theory of Electrons and Protons. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A, 126, 360-365.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1930.0013