International Journal of Astronomy and Astrophysics

Vol.06 No.02(2016), Article ID:66238,10 pages

10.4236/ijaa.2016.62012

Screening Breakdown for Finite-Range Gravitational Field and the Motion of Galaxies in the Local Group

Yuri V. Chugreev1, Konstantin A. Modestov2,3

1Bogoliubov Institute for Theoretical Problems of Microphysics, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia

2Physics Department, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia

3National Research Moscow State University of Civil Engineering, Moscow, Russia

Copyright © 2016 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 14 December 2015; accepted 2 May 2016; published 5 May 2016

ABSTRACT

The lack of Birkhoff theorem in finite-range gravitation reveals nonzero acceleration of the test body inside the massive spherical shell, as well as breakdown of screening inside the charged conductor gives rise to acceleration of the test charge. An application of this effect to the motion of galaxies in Local Group allows to constraint quintessence parameter in some massive gravitational theories.

Keywords:

Mass of the Photon, Mass of the Graviton, Shell Screening, Local Group of Galaxies, Dark Energy, Quintessence

1. Introduction

Whether photon and graviton possess nonzero rest masses is one of the most fundamental questions which have been actively examined during last decades both theoretically and experimentally in the lab and in the space [1] - [3] .

Contrary to Proca equations [4] , uniquely and undoubtedly generalizing Maxwell ones for finite range, the massive gravitation is far from its end [5] - [12] . Different theories of gravitation predict different outcomes of the same experiments, henceforth the upper bounds of the graviton mass will depend on the specific choice of such theory. We’ll consider phenomenon of breakdown of the screening effect in massive electrodynamics [4] and in finite-range theory of gravitation of Freund, Maheshwari and Schonberg [5] , and Logunov [6] [7] .

When can one anticipate an appearance of nonvanishing massive electromagnetic or, correspondingly, gravitational fields if the usual massless fields are absent (screened) in that situation? For instance, it is inside the spherically-symmetric shell. It is well known, that there is no electromagnetic field in the empty charged metal conductor, having compact (in simplest case―spherical) form [13] . Therefore, the Lorentz force acting on the test charge is equal to zero as well as its acceleration. If the gravitons have no rest mass, then according to Birkhoff theorem, inside the massive sphere the space-time is the Minkowski one, with the acceleration of the test bodies vanishing and the shell’s gravitation field being “screened”. This is clearly not the same case as electromagnetic screening, rather it is the consequence of the spherical symmetry. Nevertheless, such shielding would be broken for finite-range gravitation. Therefore in massive case one can expect that the test charge inside the charged shell and the test mass inside the massive sphere have to move with acceleration proportional (in first approximation) to the squared mass of the photon and graviton correspondingly. As we shall see, the formulas in both cases have the same form.

We’ll consider this effect and estimate the possibilities of its observation. In particular, we’ll show that the mass of the graviton will contribute to the “Hubble constant” of the galaxies flow in Local Group. It constraints the cosmological quintessence parameter in massive relativistic theory of gravitation (RTG) [6] [7] .

2. Empty Shell as the Photon Mass Detector

If the electromagnetic field has the finite range , where

, where  is the photon mass, then Maxwell equations will have the Klein-Gordon form, what was first noticed by A. Proca [4] . In arbitrary coordinates these equations are

is the photon mass, then Maxwell equations will have the Klein-Gordon form, what was first noticed by A. Proca [4] . In arbitrary coordinates these equations are

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

where ―Minkowski metrics,

―Minkowski metrics, ―vector 4-potential of the electromagnetic field,

―vector 4-potential of the electromagnetic field, ―4-current,

―4-current, ―covariant derivative with respect to metrics

―covariant derivative with respect to metrics . Throughout this work, we adopt the following units conventions

. Throughout this work, we adopt the following units conventions .

.

Consider the solution of Equation (1). Let’s note ―density of the surface charge

―density of the surface charge ,

, ―ra- dius of shell. Then Equation (1) for the scalar potential

―ra- dius of shell. Then Equation (1) for the scalar potential  yields

yields

(3)

(3)

where

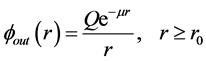

The outside solution of (2)

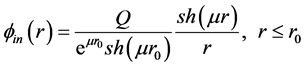

Whereas the inner solution

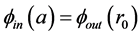

Since at the sphere surface the scalar potential is continuous

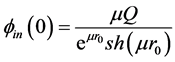

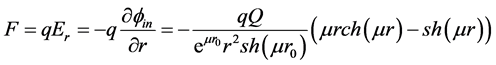

Therefore for the electric field

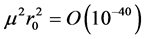

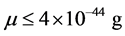

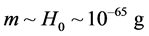

According to modern evaluations [1] - [4] the upper limit of photon mass is very small

The force (7) is directed towards the origin for the same signs of charges and it is increased as the particle comes to the surface (weak confinement). This force less than the Coulomb one

The question concerning possibility of such direct detection of photon mass in the lab or in the space, where there are no free big charges, is out of the frameworks of the paper.

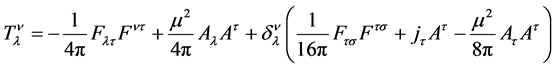

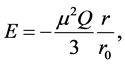

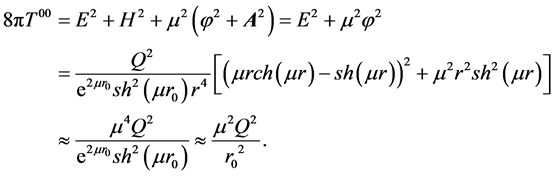

The density of energy of such electromagnetic field, i.e. 00-component of symmetric energy-momentum tensor

inside the cavity is almost constant and has the order of magnitude

Both the solution (4)-(7) and stress-energy tensor for massive electrodynamics have the correct limit

In the following section, we’ll demonstrate that there is a full analogy for the graviton of the mass m case?test body inside the spherical massive shell is no more at rest, with the force being proportional to

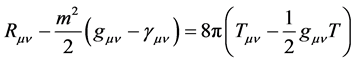

3. Empty Shell as the Graviton Mass Detector

Let’s consider the test body inside the thin spherically-symmetric perfect-fluid shell, keeping static by virtue of some external pressure. The origin of the pressure is undetermined in the frameworks of our task. In classical mechanics (with Newtonian inversed squared distance force) the test body is at rest inside the massive shell. The result keeps also valid for the exact solution of the gravitational field equations [13] . If one considers massive gravitation case, then the test body will no more be at rest in the cavity in close analogy with nonzero acceleration of the test charge in massive electrodynamics. Such cavity can be the detector of the mass of graviton. Both the sign and the value of such acceleration will be calculated in the paper.

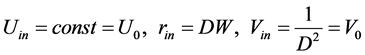

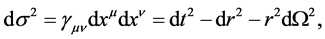

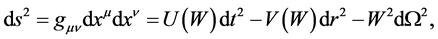

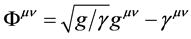

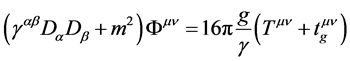

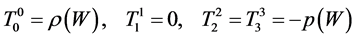

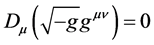

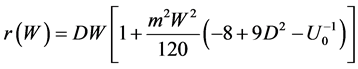

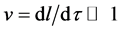

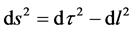

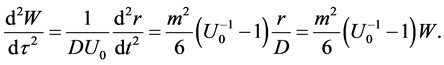

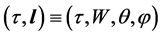

Let’s find the gravitational field created by the thin spherically-symmetric massive shell. Using standard coordinates in spherically-symmetric case one has

where r―radius in Minkowski space, W―Schwarzschild radius,

Gravitational field (

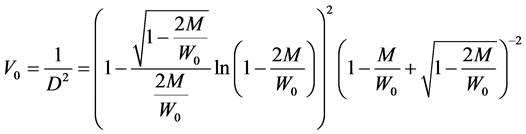

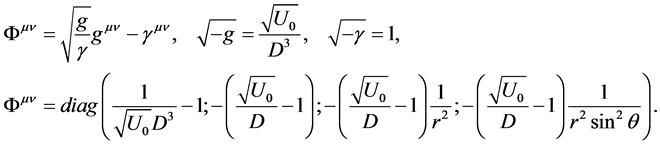

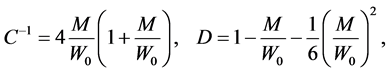

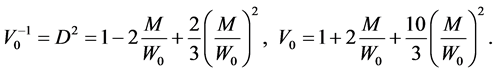

where

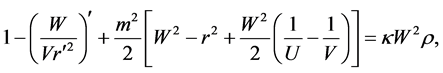

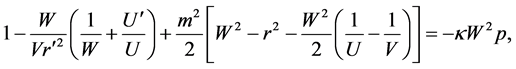

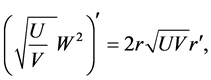

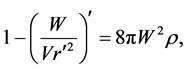

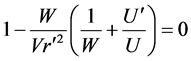

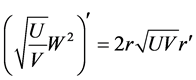

Equations (11), (12) can be rewritten in more conventional form:

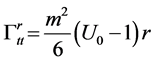

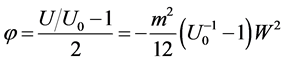

In our case from (9), (10), (13), (14), (15) one obtains

where

We shall solve Equations (16)-(18) in linear in graviton mass (which is extremely small:

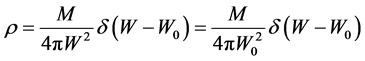

The mass density of the thin shell is given by the

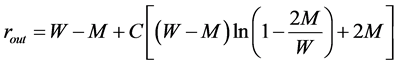

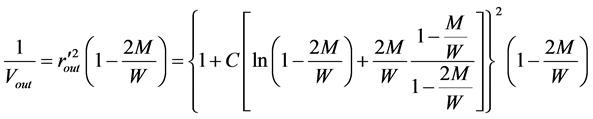

From (19), with taking into account conditions at the infinity, we obtain the external solution (

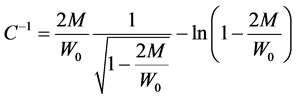

Constant C will be determined further by matching with internal solution.

Let’s consider the internal solution

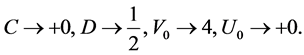

Thus in zero order approximation (

In Cartesian coordinates

In the strong field limit, when the radius of the shell goes to Schwarzschild horizon

In the weak field limit

It’s easy to show, that the function

Let’s study

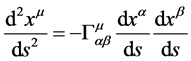

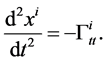

Then, one finds the value of gravitational force acting on the test particle in the cavity using geodesical equations in Riemannian space:

In nonrelativistic case

Since the only nonvanishing connection coefficient is

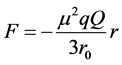

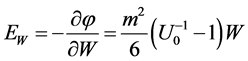

Thus, the gravitational force acting on the particle in cavity is linear in its radius, quadric in mass of graviton and directs outward the center, with factor

The interesting coincidence is that the expressions for the strength of electromagnetic field to act on the test charge and that of weak gravitational field to act on test mass are the same values, but having opposite signs:

The naive attempt to find test mass acceleration inside the shell in the frameworks of Newtonian approach gives the correct result for some choice of potential. In coordinates

which yields the correct strength of the gravitational field (acceleration),coinciding with Equation (30):

If one use the minimal upper limit for the mass of graviton

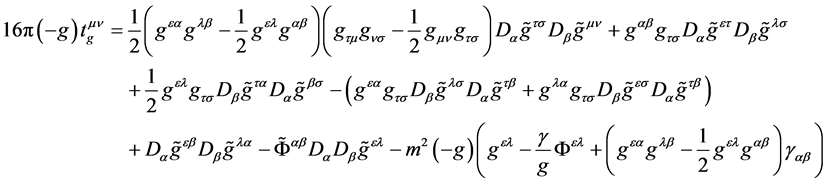

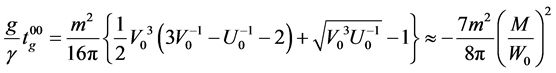

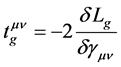

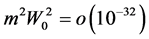

At this end, let’s calculate the energy density of the gravitational field in cavity. In linear approximation, an energy density (00-component of symmetric Hilbert stress-energy tensor, generalizing the Landau-Lifshitz com-

plex on the massive case) is constant and negative, having the order of magnitude

It differs from the energy in electromagnetic case (8) by the coefficient―7.

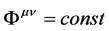

Contrary to the Pauli-Firtz massive gravitation [9] , the solutions (27)-(29) and the stress-energy tensor for finite-range theory [5] - [7] have the correct limit

4. Breakdown of Gravitational Screening―Local Hubble Flow in the Nearby Universe

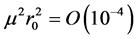

If the effect (30) is too small for the lab sizes, can it be pertinent in cosmos, when the distance W is big enough?

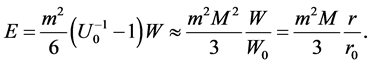

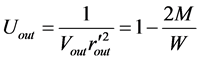

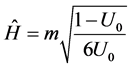

Indeed, in the cavity the local Hubble low takes place

where the “Hubble constant” equals to

This result suggests to search this effect for the group of the most massive cosmic objects, which nevertheless can be considered as the pointlike ones, moving in the mutual gravitational field, provided the dark matter should not preclude such motion, cause it (dm) should be concentrated inside these bodies. Galaxy stars don’t fit due to the distributed dark matter and not big enough distances W. Then the best option is the Local Group of Galaxies, which consists of two massive galaxies―Milky Way and M31 Galaxy and about 50 more light galaxies [14] . All these objects locate in nearby Universe at the redshifts

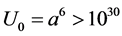

How to apply the result (30) to the Local Group of Galaxies? We can visualize the sphere containing all these galaxies with the origin in the center of mass. Outer gravitational field is the cosmological one, which is enormous at the present time [7] :

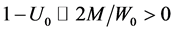

where a―FLRW-scale factor, and consequently one can neglect the Newtonian field of the very galaxies. Therefore, we have strong inequality

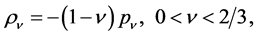

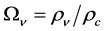

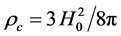

Qualitatively one can do this when notice that the dark energy (the quintessence in our case [7] [15] ) with relative density

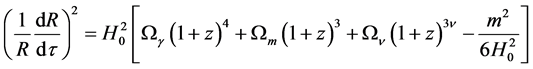

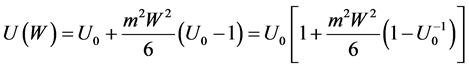

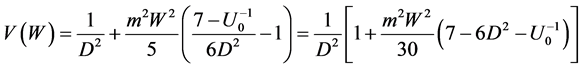

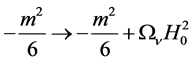

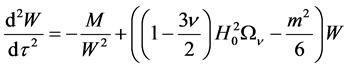

enters the Friedmannian cosmological gravitational field equations additively with m2-term [7] :

where

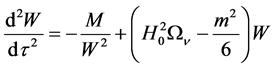

Therefore from (30), (31), we can get the equation of motion for any galaxy in Local Group, taking into account the Newtonian term

This equation describes the local Hubble flow of galaxies with bigger velocities of more distant galaxies. If the distances W are small enough, then attractive Newtonian term predominates the repulsive dark energy. The

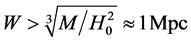

second Hubble term prevails at the distances

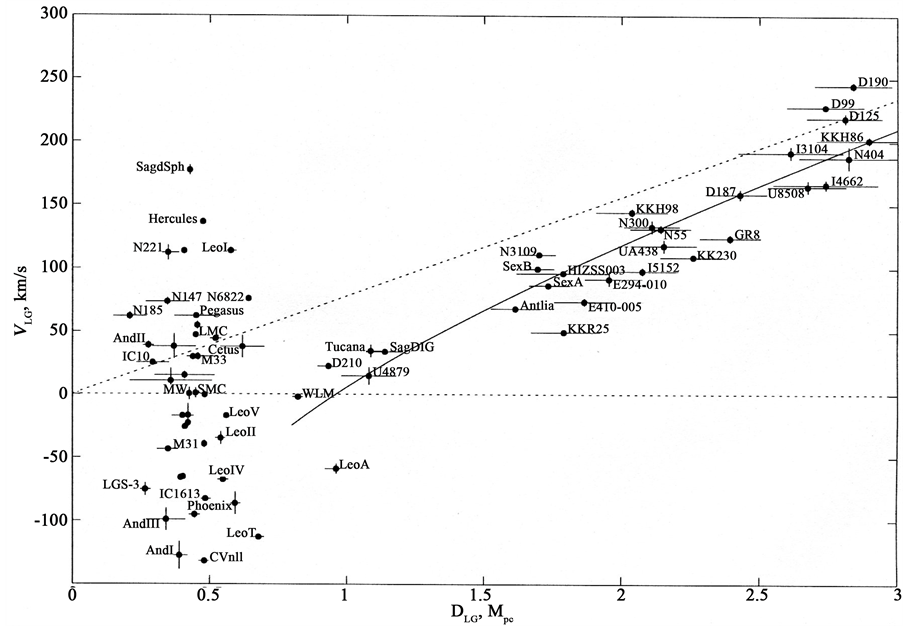

sev et al. paper [14] , based on HST data (Figure 1). Points represent galaxies with measured radial velocities and distances, calculated from the Group center of mass. It, in their turn, has 600 km/s speed with respect to the CMB [16] .

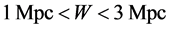

As it follows from the diagram, all the galaxies have been separated into two parts―the inner Local Group and external Local Flow. The flow galaxies have only positive velocities―they recede from the Local Group, where the motion of bodies (galaxies) has no definite direction and they move with different speeds (positive and negative).

Figure 1. Velocity-distance diagram for galaxies at distances up to 3 Mpc. Each dot corresponds to a galaxy with measured distance and radial velocity in the reference frame associated with the center of mass of the Local group. The velocities are deemed positive if they are directed away from the group center.

Let’s point out, that such simple spherically-symmetric model, where The Local Group is represented by the mass M, and the galaxies-by the pointlike bodies with the masses much less than M, on the backgroung of dark energy with constant density given by cosmological constant, first considered by Chernin, Teericorpi and Baryshev [16] - [18] in the frameworks of General Relavity.

Rigorous calculation of the model in relativistic theory of gravitation [19] with quintessence as the dark energy(cosmological term in the theory [7] is ruled out by the causality principle)have been performed in [19] , where the final result

is very close to (32) and differs only by the factor

Comparing (33) with the results of observations [14] and using independent evaluation of

so the factor

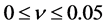

Strong limits of quintessence parameter

Acknowledgements

Authors thank A. A. Logunov, M. A. Mestvirishvili and Yu. V. Baryshev for useful discussions and A. V. Selikhov for support.

Cite this paper

Yuri V. Chugreev,Konstantin A. Modestov,1 1, (2016) Screening Breakdown for Finite-Range Gravitational Field and the Motion of Galaxies in the Local Group. International Journal of Astronomy and Astrophysics,06,145-154. doi: 10.4236/ijaa.2016.62012

References

- 1. Goldhaber, A.S. and Nieto, M.M. (1971) Terrestrial and Experimental Limits on the Photon Mass. Review of Modern Physics, 43, 277-296.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.43.277 - 2. Goldhaber, A.S. and Nieto, M.M. (2010) Photon and Graviton Mass Limits. Review of Modern Physics, 82, 939-979.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.82.939 - 3. Chibisov, G.V. (1976) Astrophysical Upper Limits on the Photon Rest Mass. Soviet Physics-Uspekhi, 19, 624-626.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1070/PU1976v019n07ABEH005277 - 4. Proca, A. (1936) Sur les Photons et les Particules charge pure. Comptes Rendus de l’Academie des Sciences, 203, 709-711.

- 5. Freund, P.G.O., Maheshwari, A. and Schonberg, E. (1969) Finite Range Gravitation. Astrophysical Journal, 157, 857-867.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/150118 - 6. Logunov, А.А. (2006) The Relativistic Theory of Gravitation. Nauka, Moscow (in Russian).

Logunov, А.А. (2002) The Theory of Gravity.

http://arxiv.org/abs/gr-qc/0210005 - 7. Gershtein, S.S., Logunov, А.А., Mestvirishvili, M.A. and Tkachenko, N.P. (2005) The Evolution of the Universe in the Field Theory of Gravitation. Physics of Particles and Nuclei, 36, 1003-1050.

- 8. Visser, M. (1999) Mass for the Graviton. General Relativity and Gravitation, 30, 1727-1728.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1026611026766arxiv.org/abs/gr-qc/9705051 - 9. Rubakov, V.A. and Tinyakov, P.G. (2008) Infrared-Modified Gravities and Massive Gravitons. Physics-Uspekhi, 51, 759-792. http://ufn.ru/en/articles/2008/8/a/

- 10. Babak, S.V. and Grishchuk, L.P. (2003) Finate-Range Gravity and Its Role in Gravitational Waves, Black Holes and Cosmology. International Journal of Modern Physics, D12, 1905-1959.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/S0218271803004250 - 11. Hinterbichler, K. (2012) Theoretical Aspects of Massive Gravity. Review of Modern Physics, 84, 671-710.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.84.671 - 12. de Rham, C. (2014) Massive Gravity. Living Reviews in Relativity, 17, 7-189.

http://dx.doi.org/10.12942/lrr-2014-7 - 13. Landau, L.D. and Lifshitz, E.M. (1980) The Classical Theory of Fields. 4th Edition, Butterworth-Heinemann, Elsevier, Oxford.

- 14. Karachentsov, I.D., Kashibadze, O.G., Makarov, D.I. and Tully, R.B. (2009) The Hubble Flow around the Local Group. Monthly Notices of Royal Astronomical Society, 393, 1265-1284.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.14300.x - 15. Chugreev, Yu.V., Mestvirishvili, M.A. and Modestov, K.A. (2007) Quintessence Scalar Field in the Relativistic Theory of Gravity. Theoretical and Mathematical Physics, 152, 1342-1350.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11232-007-0118-9 - 16. Chernin, A., Teerikorpi, P. and Baryshev, Yu. (2003) Why Is the Hubble Flow So Quiet? Advanced Space Researches, 31, 479-497.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0273-1177(02)00731-7arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/0012021 - 17. Chernin, A.D. (2008) Dark Energy and Universal Antigravitation. Physics-Uspekhi, 51, 253-282.

http://ufn.ru/en/articles/2008/3/c/ - 18. Chernin, A.D. (2013) Dark Energy in the Nearby Universe: HST Data, Nonlinear Theory and Computer Simulations. Physics-Uspekhi, 56, 704-709.

http://ufn.ru/en/articles/2013/7/e/ - 19. Chugreev, Yu.V. (2016) Dark Energy and the Mass of Graviton in Nearby Universe. Physics of Particles and Nuclei Letters, 13, 38-45.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11232-007-0118-9 - 20. Planck Collaboration (2015) Planck 2015 Results. Cosmological Parameters.

arxiv.org/abs/1502.01589v2