Open Journal of Modelling and Simulation

Vol.05 No.04(2017), Article ID:78544,29 pages

10.4236/ojmsi.2017.54015

Quantum Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Warm Dense Li Plasma

Sylvian Kahane

P.O. Box 1630, Omer, Israel

Copyright © 2017 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: March 22, 2017; Accepted: August 15, 2017; Published: August 18, 2017

ABSTRACT

The behavior of Li warm plasma (i.e. T in 1 eV range) is reported for a range of temperatures ( ) and densities (

) and densities ( ), spanning moderate to dense conditions. Quantum Molecular Dynamics (QMD), in Carr-Parinello approach, is used to advance and equilibrate an ensemble of 54 Li atoms at desired temperature and density. The charge distribution and ions positions are further input in a DFT finite temperature calculation, producing, self consistently, a large number of energy levels (300 - 1500) and occupation numbers, from which real and imaginary parts of the dielectric function are obtained. Optical quantities like index of refraction, reflectivity, absorption coefficients and Rosseland means are deduced. Zero frequency static conductivity

), spanning moderate to dense conditions. Quantum Molecular Dynamics (QMD), in Carr-Parinello approach, is used to advance and equilibrate an ensemble of 54 Li atoms at desired temperature and density. The charge distribution and ions positions are further input in a DFT finite temperature calculation, producing, self consistently, a large number of energy levels (300 - 1500) and occupation numbers, from which real and imaginary parts of the dielectric function are obtained. Optical quantities like index of refraction, reflectivity, absorption coefficients and Rosseland means are deduced. Zero frequency static conductivity , diffusion coefficients and a Hugoniot curve are calculated.

, diffusion coefficients and a Hugoniot curve are calculated.

Keywords:

QMD, FTDFT, Opacity, Rosseland

1. Introduction

Gas discharge is often used in plasma investigations. The densities achieved run from 1014 electrons/cc for a conventional setup up to 1018 for more intricate techniques, like capillary gas discharge. In tokomaks the density is also at the 1014 mark. In our sun, a giant plasma laboratory, there are a variety of densities, 105 in solar corona, 108 in chromosphere, 1015 in photosphere etc. Plasma studies hence, were traditionally concerned with low densities environments, very much below the nominal solid density at 1023.

With the advent of new facilities and techniques, like inertial confinement fusion (ICF), National Ignition Facility at LLNL, high energy density physics experiments, shock experiments etc., the interest is shifting toward a regime of warm dense matter (WMD). Warm means temperatures in the range 103 - 106 K, but typically near 10,000 K (1 eV), while dense encompass a range from a fraction of STP density  (~1021 atoms/cc), to many times

(~1021 atoms/cc), to many times  (~1025 atoms/ cc). In this regime the plasma is populated by free electrons, ions (positive or negative), atoms, molecules if the chemistry permits it, or aggregates of two or more ions: dimmers, trimmers, etc. All these populations are very dynamic, evolving all the time, due to mutual interactions through collisions, ionization, recombination, chemical reactions and so forth.

(~1025 atoms/ cc). In this regime the plasma is populated by free electrons, ions (positive or negative), atoms, molecules if the chemistry permits it, or aggregates of two or more ions: dimmers, trimmers, etc. All these populations are very dynamic, evolving all the time, due to mutual interactions through collisions, ionization, recombination, chemical reactions and so forth.

To model such an environment a most appropriate tool is the molecular dynamics (MD) in which the atoms (ions) are followed individually through their interactions and trajectory in space, time and energy. In classical MD the ions interact through an empirical potential fixed in time (the electrons play no role), therefore the dynamicity of the system is not fully accounted. Contrary, in quantum molecular dynamics (QMD) the electrons are given an equal role with the ions, and even more, they are treated fully quantum mechanically in the framework of density functional theory (DFT). The fixed potential is no longer needed and the interactions are described realistically depending on time and space. The QMD is obviously the tool of choice but comes at a price, only small ensembles of atoms and relatively short times can be simulated.

Planetary interiors are studied in the WMD regime [1] [2] and also white dwarfs, where average densities are 106 g/cc and the effective temperature, deduced from luminosity, is in the range 8000 - 16,000 K for most of them [3] . White dwarfs have very low remnants of He (≤1%) and H (≤0.01%) which form a thin and very opaque atmosphere, hence there is interest in their optical properties (index of refraction, reflectivity, absorption coefficient) which are significant for the radiation transport.

Electric conductivity, dielectric function and all the other optical properties can be obtained within finite temperature density functional theory (FTDFT), as formulated by Mermin [4] , using the ions configurations generated in a QMD calculation coupled with the Kubo-Greenwood (KG) [5] [6] formula. This three steps approach, QMD + FTDFT + KG, was used in the last 10 - 15 years for a number of calculations, mainly on Hydrogen and Deuterium [7] [8] [9] , relevant for stellar interiors and atmospheres as well as for ICF pellets, but also on Aluminium [10] [11] , Sodium [12] and Iron [13] , relevant for planetary interiors, particularly Earth.

Large astrophysical data bases, like OPAL, containing opacities (i.e. absorption coefficients) and their Rosseland means, concentrate on a number of elements defined as belonging to stellar, or more precisely, to solar atmosphere. Lithium is not included in the solar composition and has not received to much attention regarding its optical properties.

Nevertheless, Lithium, which is considered a simple metal, is slightly more complex than H, D, and He and it is worthwhile to investigate it in the frame- work of the above formalism. Indeed a recent paper [14] reported results for densities in the range 0.1 - 10 g/cc and temperatures of several hundred up to 10,000 K.

The goal of the present work is to extend Lithium investigation to a higher temperature range from 10,000 K to 50,000 K, while maintaining realistic den- sities close to those of the solid. This region lacks proper experimental data and will be of interest in stellar scenarios different from our sun.

2. Theoretical Formalism

The response of a medium to an electromagnetic wave (like light) is charac- terized by its dielectric function . The optical properties are derived from the frequency dependent, long wavelength

. The optical properties are derived from the frequency dependent, long wavelength , complex dielectric function:

, complex dielectric function:

(1)

(1)

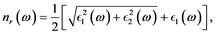

The real  and imaginary

and imaginary  parts of the index of refraction are [15] :

parts of the index of refraction are [15] :

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

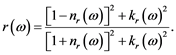

which together are giving the reflectivity:

(4)

(4)

The following relations are useful:

(5)

(5)

(6)

(6)

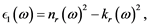

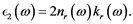

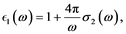

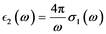

The dielectric function will be actually computed (see Section 3.3) from the complex conductivity :

:

(7)

(7)

(8)

(8)

The imaginary part of conductivity is related to the real part of dielectric function and vice versa.

The absorption coefficient is [16] :

and with the help of Planck distribution:

the Rosseland mean opacity is obtained as [17] :

where the absorption coefficient

Perrot [16] defines a true absorption coefficient in dielectric material as:

and argues that the Rosseland mean opacity expression should be modified as:

The integrations above extend to

The Planck mean,

or with Perrot [16] true absorption coefficient:

3. Calculation of the Dielectric Function

The calculation proceeds in three steps by a procedure well established in the literature: Mazevet et al. [10] , Silvestrelli [11] , Desjarlais et al. [9] .

First, an ensemble of Li atoms is equilibrated, at desired density and tem- perature, by a QMD calculation. When the system is stable, the QMD run is sampled a number of times. The sampled configurations, consisting of ions coordinates and total charge distribution, serves as input to a second finite temperature density functional (FTDFT) step. In this step a large number of energy levels, occupation numbers and respective Kohn-Sham electron wave- functions are calculated self consistently (SCF). These last products are the key ingredients, in a final step, for calculating the real conductivity

The first two steps were calculated with the Quantum ESPRESSO [18] software system cp.x and pw.x programs. For the third step a modified form of the epsilon.x program of Quantum ESPRESO was implemented.

3.1. The QMD Step

An ultrasoft pseudopotential for Li, taken from Vanderbilt uspp-7.3.4 code distribution [19] , was chosen for the QMD calculation. The potential, for one valence electron, was tested for convergence to the experimental lattice parameter of bcc Li of 3.49 Å, Figure 1.

The found minimum is 3.56 Å. The cutoff energy chosen for subsequent QMD was 20 Ry, which gives a minimum of only ≈ 2 mRy above the best

Figure 1. Vanderbilt USPP. Total energy versus lattice parameter and cutoff.

minimum at a cutoff of 60 Ry.

As is customary in QMD only the G k point of the Brillouin zone is sampled. A time step of 4 AU (≈0.1 fs) was used, implying 10,000 steps/ps. The initial configuration of 54 Li atoms, at a given density in a simple cubic cell, was generated with the PACKMOL [20] program, disregarding any symmetry. Periodicity in all 3 dimensions is assumed. The system was brought to ground state and relaxed to eliminate too strong force components. The system was advanced in time in NVT (canonical ensemble) mode with Nosé thermostats on both ions and electrons, kept at equal temperatures (i.e. thermal equilibrium

For the lowest density included in the calculations

Other quantities of interest produced by a QMD simulation are the velocity

Figure 2. A part of the QMD run history at

Figure 3. Radial distribution function

autocorrelation function, the mean square displacement, Figure 5, from which the diffusion coefficient can be obtained either by Einstein relation or by a Green-Kubo relation [24] , and the pressure at a given density and temperature, Figure 6. From pressures, densities and temperatures, a numerical equation of

Figure 4. Translational order parameter [23] , consistent with a value of zero (averrage value

Figure 5. Velocity autocorrelation and mean square displacement at

Figure 6. Pressure as a function of simulation time. A block average yields

state (EOS) can be constructed (for the limited range of simulations) by a method given by Lenosky et al. [8] .

3.2. The FTDFT Step

In the last 1 ps of the QMD run a snapshot of the system was taken at every 2000 steps (0.2 ps), 5 snapshots in all. The purpose is to average over the results from the different snapshots. These snapshots include ions positions, electric charge distribution, Kohn-Sham electrons wavefunctions (i.e. their expansion in plane waves) and other miscellaneous information regarding inverse lattice G vectors, their stars, etc. This information was fed into the pw.x (PWscf-plane waves self consistent field) program of Quantum ESSPRESO. Actually only the ions positions (which will be kept fixed) and the electric charge distribution were needed. In this step a PAW (Projector Augmented Wave) pseudopotential of Blöchl type [25] was employed. The change in pseudopotential is necessary due to difficulties in calculating dipole matrix elements with ultrasoft pseudo- potentials, see next section discussion.

The actual PWA pseudopotential was constructed with the atompaw program of Holzwarth at al. [26] . The input was taken directly from their examples with a slight modification of adding a 4-th basis function, enabling decent fits to the logarithmic derivatives, Figure 7 (all the electrons were considered to be valence electrons, no core). The exchange-correlation functional is of PBE type [27] , and the electronic calculation is done in the Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA). The same approximation is used further in the scf calculations done with pw.x.

An analysis similar to Figure 1 yields, for the PAW pseudpotential, an equilibrium bbc Li lattice parameter of 3.46 Å (closer to the experimental 3.49 Å

Figure 7. Logarithmic derivative fits. Full line―all electron calculation; dots―PWA pseudopotential calculation.

compared with the uspp result) and a cutoff of

The finite temperature density functional calculation, in the sense of Mermin [4] , is realized in PWscf by imposing a Fermi-Dirac smearing of width

The density of states, Figure 9, shows a high and localized peak of the two 1s electrons, and a loose structure, below and above the Fermi energy, coming from the 2s (with some 2p mixture) electrons.

3.3. Conductivity Calculation

Following Harrison [28] , the current in a metal is assumed to be of the form

with

A calculation of the expectation value of

Figure 8. Occupation numbers as a function of electronic levels energy. Bottom line (blue)

Figure 9. DOS―the density of states.

In the notation of [13] [15] , with atomic units (

with

The operator

The PAW potential is an all-electron local potential and the Equation (18) is valid [30] . For this reason the majority of previous works preferred to use a PAW potential.

The FTDFT step 2 produces a pseudo-wavefunction

In the present work the matrix elements are approximated by calculating with the pseudo-wavefunction:

where

The

the broadening parameter

The BZ is sampled at a number of special k points chosen from Monkhorst- Pack [32] sets without symmetries, i.e. all the k points have equal weights. The final conductivity is:

with

Figure 10 presents some details of

Figure 10.

and Equation (8) it is obvious that the natural units of conductivity are units of frequency. Indeed some older papers show conductivity in sec−1. More recent papers prefer to quote the conductivity in units of inverse resistivity, namely [Ohm・cm]−1. Figure 10 follows this convention. Panel 1) shows the full

The calculated

with

The sum rule was fulfilled at 90% - 96% level at higher densities (where a low number of levels is sufficient to reach very low occupation numbers) and worse at lower densities where very large number of levels are needed.

The imaginary part

Some other quantities of interest obtained from the calculations in this section are presented in Figure 11. The Electron Energy Loss Spectrum (EELS) is defined from the dielectric function as:

the plasmon peak is apparent.

The absorption coefficient can be compared with one given in [15] for LiH at

Figure 11. The absorption coefficient

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. EOS

The relation of the three thermodynamic quantities

The QMD calculations of stage 1 were performed at 36 pairs

Following Lenosky et al. [8] an internal energy per atom is defined as:

where N―the number of atoms in simulation,

where

The two Equations (26), (27) apparently can be fitted independently. There- fore an additional well known thermodynamic condition, providing a link between the two equations, is imposed as a constrain:

The right side is in

or conversely:

The numerical factors take care of units. An inspection of Table 1 and Table 2 reveal the presence of six couples cij-di-1j in the restricted set, hence reducing the number of independent coefficients from 17 to 11. The particular couple c11-d01 is problematic, in both Equations (29) or (30) an indefinite 0/0 indices ratio is present. Hence, because the thermodynamic constrain is not actually fixing the relation between these two parameters, they were left both free, rising the number of fitted parameters to 12.

The thermodynamic constrain was implemented as a penalty function (PF) added to the

where

At the end of the fit

Table 1. Fitted EOS coefficients

Table 2. Fitted EOS coefficients

average discrepancy in P is 5% (with 5 points

The fitted parameters are presented in Table 1 and Table 2.

4.1.1. Isotherms

The EOS is studied experimentally in compression experiments such as modern diamond anvil cell techniques plus X-ray diffraction or older piston cylinder apparata. In these type of experiments the temperature T is constant, usually the room temperature, producing

Boettger and Trickey (BT) [35] calculated, by a LMTO technique, a theoretical cold EOS, without a T dependence. It made its way as the cold part of EOS 2293 [36] in the SESAME [37] database. Their cold EOS fits nicely the experimental points in Figure 13. It can be seen that the 10,000 K isotherm is less stiff (lower slope) at high densities (lower volumes). This trend continues in Figure 12 with lower and lower slopes at higher temperatures.

4.1.2. Hugoniot

Another technique to study EOS is by shock experiments. In these experiments, starting from an initial state

Figure 12. Pressure in GPa as a function of T and ρ. QMD calculations-symbols. EOS fit-lines.

Figure 13. Experimental [33] [34] and theoretical [35]

which can be attained by applying different shock intensities, when starting from the same initial conditions. Noting by

What is actually measured are two velocities:

In Equation (32) apparently there is no explicit dependence on temperature but an EOS is an absolutely prerequisite for solving it (one needs 3 equations for 3 unknowns).

The chosen initial conditions where

Figure 14. Hugoniot curves. The pressure

Data from the LASL shock dat a library [42] are below the range of the calculated Hugoniot. Data of Bakanova et al. [43] have some overlap with the calculated range, but was criticized in [41] as being too soft (i.e. predicting too low pressures with increasing density) and probably in error. It is definitely below the calculated Hugoniot. The Hugoniot curve of Young and Ross [41] is based on only 4 points given in their paper, hence its fractured appearance. The large discrepancy between their curve and ours is, in part, due to lack of points between their last value at

Our values close to these V points are 194 GPa and 92 GPa, respectively, so while at

Numerical data for the calculated Hugoniot curve are presented in Table 3.

4.2. Sylvian Kahane

DC conductivity

The DC conductivity is the static limit

Table 3. Li Hugoniot data.

Kietzmann’s

In the work of Desjarlais, Kress and Collins [9] on Al, an inversion region in the

Bastea and Bastea [45] and Fortov et al. [46] measured the conductivity in Li. Both works used the quasi-isoentropic technique in which a shock wave is traveling back and forth in the sample, reflected by the anvils (saphire or steel), increasing the pressure. In [45] the reported temperatures varied from 2000 K to 7000 K and P reached 180 GPa, while in [46] T was lower than 3000 K and P reached 210 GPa, thus both are below the present calculations range of T.

The conductivity and other quantities dependence on temperature is shown in Table 4.

The values of the diffusion coefficient D are very well reproduced by an Arhenius function

Figure 15. DC conductivity as a function of density.

Table 4. Trends in conductivity, pressure and diffusion coefficients as a function of tem- perature.

The reduced diffusion coefficient is defined as

4.3. Rosseland Mean Opacity

The absorption coefficient

Some of the present results are compared in Figure 16 with results based on opacities calculated with the atomic modeled plasma by collisional-radiative FLYCHK code [48] .

In the atomic model the attenuation of radiation involves electron transitions (bound-bound, bound-free, free-free) in an isolated atom. It is appropriate, hence, mainly for diluted plasmas or gases. When the density is larger the interaction between neighboring atoms begins to come into play. If this density effect is still weak, it can be treated as a perturbation in the framework of the atomic model, but when the density is large and the atoms close, the isolated model will fail and a more collective approach is needed. The QMD + FTDFT

Figure 16. Rosseland mean opacity. Blue lines―present QMD + FTDFT calculations, red lines―calculated with the atomic code FLYCHK [48] .

offers such alternative model, in which the interaction with the neighbors is built-in in the QMD step, while the electrons wavefunctions (needed for the transitions calculations) are obtained in the FTDFT step from a collective model, not resembling at all the isolated atom. The versatility of the QMD is illustrated in Figure 17 which shows the Li atoms at some position in time when 4 out of the 54 atoms clearly formed two Li2 dimmers in which they are very close and, hence, the electronic wavefunctions are severely distorted by the presence of the neighbor atom.

Figure 16 shows that the QMD + FTDFT Rosseland mean opacities vary much slower compared with the corresponding atomic ones. This is in qualitative agreement with the results for hydrogen from [50] . To understand more on the differences between the present and atomic approaches one has to look at the absorption coefficients in Figure 18.

There is a sharp contrast below ~3 - 4 eV (the plasma frequency for the re- spective

Figure 17. Formation of Li2 dimmers in the course of the QMD simulations (a pseudo electron density iso-surface, created by the XCrysDen [49] program, is displayed). The distances between the Li ions in the dimmers are 0.65 Å and 0.75 Å.

Figure 18. Absorption coefficient compared with FLYCHK calculation.

bound electron to induce a transition, so one can expect some flat opacity at low energies below

The K-edge of the FLYCHK

Neither the order of magnitudes differences in the absorption coefficient at low energies, or the differences at the K-edge, are really influencing the QMD + FTDFT vs. FLYCHK Rosseland means. As can be seen in Figure 18 the weighting function

4.4. Experimental Optical Data

Experimental optical data on Li metal was taken from an Internet source [51] , without proper credits, from Callcot and Arakawa (C&A) [52] and from Mathewson and Myers [53] . The data was measured, most probably, at room temperature. It is hard to estimate if the density is the nominal density (

In Figure 19 these experimental data are compared with the QMD + FTDFT calculation at

Figure 19. Experimental optical properties of Li metal, the index of refraction: real

devided by its authors in two regions. In the range

5. Summary

This work presents Quantum Molecular Dynamics and Finite Temperature DFT calculations, from which optical and electrical properties of warm Lithium plasma are obtained. It covers a range of temperatures and densities not in- vestigated previously bringing, therefore, fresh new information on dense plasma

Figure 20. Experimental dielectric function. Symbols: red [53] ; magenta # [52] , from the unsafe region

characteristics.

Detailed theoretical backgrounds were discussed:

・ Specifically the connections between the calculations and the dielectric func- tion.

・ Extraction of the optical properties from the dielectric function.

・ Use of pseudopotentials both in the QMD and the DFT calculations.

・ Strength and the problems in using the PAW pseudopotential for the DFT and the dielectric function calculations.

Moreover, also other computational techniques, of more heuristic approach, were employed resulting in a formula for Lithium Equation of State at high temperature and densities.

Whenever possible comparison with experimental data was shown, even when the temperature range was different.

Conclusion: New theoretical data for Rosseland absorption mean, indexes of refraction

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Dr. Yuri Ralchenko from NIST, for his help with the FLYCHK program.

Cite this paper

Kahane, S. (2017) Quantum Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Warm Dense Li Plasma. Open Journal of Modelling and Simulation, 5, 189-217. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojmsi.2017.54015

References

- 1. Saumon, D. and Guillot, T. (2004) Shock Compression of Deuterium and the Interiors of Jupiter and Saturn. The Astrophysical Journal, 609, 1170-1180.

https://doi.org/10.1086/421257 - 2. Knudson, M.D., et al. (2012) Probing the Interiors of the Ice Giants: Shock Compression of Water to 700 GPa and 3.8 g/cm3. Physical Review Letters, 108, Article ID: 091102.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.091102 - 3. Fontaine, G., Brassard, P. and Bergeron, P. (2001) The Potential of White Dwarf Cosmochronology. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 113, 409-435.

https://doi.org/10.1086/319535 - 4. Mermin, N.D. (1965) Thermal Properties of the Inhomogeneous Electron Gas. Physical Review, 137, A1441-A1443.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.137.A1441 - 5. Kubo, R. (1957) Statistical-Mechanical Theory of Irreversible Processes. I. General Theory and Simple Applications to Magnetic and Conduction Problems. Journal of the Physical Society of Japan, 12, 570-586.

https://doi.org/10.1143/JPSJ.12.570 - 6. Greenwood, D.A. (1958) The Boltzmann Equation in the Theory of Electrical Conduction in Metals. Proceedings of the Physical Society (London), A71, 585.

https://doi.org/10.1088/0370-1328/71/4/306 - 7. Collins, L., Kwon, I., Kress, J., Troullier, N. and Lynch, D. (1995) Quantum Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Hot, Dense Hydrogen. Physical Review E, 52, 6202-6219.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.52.6202 - 8. Lenosky, T.J., Sickman, S.R., Kress, J.D. and Collins, L.A. (2000) Density-Functional Calculation of the Hugoniot of Shocked Liquid Deuterium. Physical Review B, 61, 1-4.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.61.1 - 9. Desjarlais, M.P., Kress, J.D. and Collins, L.A. (2002) Electrical Conductivity for Warm, Dense Aluminum Plasmas and Liquids. Physical Review E, 66, Article ID: 025401(R).

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.66.025401 - 10. Mazevet, S., Dejarlais, M.P., Collins, L.A., Kress, J.D. and Magee, N.H. (2005) Simulations of the Optical Properties of Warm Dense Aluminum. Physical Review E, 71, Article ID: 016409.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.71.016409 - 11. Silvestrelli, P.L. (1999) No Evidence of a Metal-Insulator Transition in Dense Hot Aluminum: A First-Principles Study. Physical Review B, 60, Article ID: 016382.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.60.16382 - 12. Pozzo, M., Dejarlais, M.P. and Alfe, D. (2011) Electrical and Thermal Conductivity of Liquid Sodium from First-Principles Calculations. Physical Review B, 84, Article ID: 054203.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.84.054203 - 13. Alfie, D., Pozzo, M. and Desjarlais, M.P. (2012) Lattice Electrical Resistivity of Magnetic BCC Iron from First-Principles Calculations. Physical Review B, 85, Article ID: 024102.

- 14. Kietzmann, A., Redmer, R., Desjarlais, M. and Mattson, T.R. (2008) Complex Behavior of Fluid Lithium under Extreme Conditions. Physical Review Letters, 101, Article ID: 070401.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.070401 - 15. Horner, D.A., Kress, J.D. and Collins, L.A. (2008) Quantum Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Warm Dense Lithium Hydride: Examination of Mixing Rules. Physical Review B, 77, Article ID: 064102.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.77.064102 - 16. Perrot, F. (1996) New Approximation for Calculating Free-Free Absorption in Hot Dense Plasmas. Laser and Particle Beams, 14, 731-748.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0263034600010430 - 17. Seaton, M.J. (1987) Atomic Data for Opacity Calculations. I. General Description. Journal of Physics B: Atomic and Molecular Physics, 20, 6363.

https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3700/20/23/026 - 18. Giannozzi, P., et al. (2009) Quantum Espresso: A Modular and Open-Source Software Project for Quantum Simulations of Materials. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter, 21, Article ID: 395502.

https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/21/39/395502 - 19. Vanderbilt, D. (2002).

http://physics.rutgers.edu/~dhv/uspp/uspp-cur/Work/003-Li/003-Li-gpw-n-campos/ - 20. Martinez, L., Andrade, R., Birgin, E.G. and Martinez, J.M. (2009) PACKMOL: A Package for Building Initial Configurations for Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 30, 2157-2164.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.21224 - 21. Car, R. and Parrinello, M. (1985) Unified Approach for Molecular Dynamics and Density-Functional Theory. Physical Review Letters, 55, 2471.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.55.2471 - 22. Marx, D. and Hutter, J. (2009) AB Initio Molecular Dynamics: Basic Theory and Advanced Methods. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511609633 - 23. Allen, M.P. and Tildesley, D.J. (1991) Computer Simulation of Liquids. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- 24. Frenkel, D. and Smit, B. (2002) Understanding Molecular Simulations. 2nd Edition, Academic Press, San Diego.

- 25. Blochl, P.E. (1994) Projector Augmented-Wave Method. Physical Review B, 50, 17953-17979.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.50.17953 - 26. Holzwarth, N.A.W., Tackett, A.R. and Matthews, G.E. (2001) A Projector Augmented Wave (PAW) Code for Electronic Structure Calculations, Part I: Atompaw for Generating Atom-Centered Functions. Computer Physics Communications, 135, 329-347.

- 27. Perdew, J.P., Burke, K. and Ernzerhof, M. (1996) Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Physical Review Letters, 77, 3865-3868.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865 - 28. Harrison, W.A. (1970) Solid State Theory. McGraw-Hill, New York.

- 29. Recoules, V. and Crocombette, J.-P. (2005) Ab Initio Determination of Electrical and Thermal Conductivity of Liquid Aluminum. Physical Review B, 72, Article ID: 104202.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.72.104202 - 30. Mazevet, S., Torrent, M., Recoules, V. and Jollet, F. (2010) Calculations of the Transport Properties within the PAW Formalism. High Energy Density Physics, 6, 84-88.

- 31. Gonze, X. (1997) First-Principles Responses of Solids to Atomic Displacements and Homogeneous Electric Fields: Implementation of a Conjugate-Gradient Algorithm. Physical Review B, 55, 10337-10354.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.55.10337 - 32. Monkhorst, H.J. and Pack, J.D. (1976) Special Points for Brillouin-Zone Integrations. Physical Review B, 13, 5188-5192.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.13.5188 - 33. Hanfland, M., Loa, I., Syassen, K., Schwarz, U. and Takemura, K. (1999) Equation of State of Lithium to 21 GPa. Solid State Communications, 112, 123-127.

- 34. Vaidya, S.N., Getting, I.C. and Kennedy, G.C. (1971) The Compression of the Alkali Metals to 45 kbar. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids, 32, 2545-2556.

- 35. Boettger, J.C. and Trickey, S.B. (1985) Equation of State and Properties of Lithium. Physical Review B, 32, 3391-3398.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.32.3391 - 36. Li (1988) Sesame Equation of State Number 2293. Los Alamos Report No. LA-11338-MS.

- 37. SESAME: The Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, Equation of State Database. Report No. LA-UR-92-3407. (Unpublished)

- 38. Zeldovich, Y. and Raizer, Y. (2002) Physics of Shock Waves and High-Temperature Hydrodynamic Phenomena. Dover Publications, Mineola.

- 39. Rice, M.H. (1965) Pressure-Volume Relations for the Alkali Metals from Shock- Wave Measurements. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids, 26, 483-492.

- 40. MINUIT. CERN Program Library D506.

- 41. Young, D.A. and Ross, M. (1984) Theoretical High-Pressure Equations of State and Phase Diagrams of the Alkali Metals. Physical Review B, 29, 682-691.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.29.682 - 42. Marsh, S.P. (1980) Lasl Shock Hugoniot Data. University of California Press, Berkeley.

- 43. Bakanova, A.A., Dudoladov, I.P. and Trunin, R.F. (1965) Compression of Alkali Metals by Strong Shock Waves. Soviet Physics, Solid State, 7, 1307-1313.

- 44. Johnson, J.D. (1977) General Features of Hugoniots—II. Los Alamos Report No. LA-13217-MS.

- 45. Bastea, M. and Bastea, S. (2002) Electrical Conductivity of Lithium at Megabar Pressures. Physical Review B, 65, Article ID: 193104.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.65.193104 - 46. Fortov, V.E., Yakushev, V.V., Kagan, K.L., Lomonosov, I.V., Postnov, V.I., Yakusheva, T.I. and Kuryanchik, A.N. (2001) Anomalous Resistivity of Lithium at High Dynamic Pressure. JETP Letters, 74, 418.

- 47. Hansen, J.P., McDonald, I.R. and Pollock, E.L. (1975) Statistical Mechanics of Dense Ionized Matter. III. Dynamical Properties of the Classical One-Component Plasma. Physical Review A, 11, 1025-1039.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.11.1025 - 48. Chung, H.K., Lee, R.W., Chen, M.H. and Ralchenko (2008) Flychk@Nist.

http://nlte.nist.gov/FLY - 49. Kokalj, A. (1999) XCrySDen—A New Program for Displaying Crystalline Structures and Electron Densities. Journal of Molecular Graphics and Modelling, 17, 176-179.

http://www.xcrysden.org/ - 50. Mazevet, S., Collins, L.A., Magee, N.H., Kress, J.D. and Keady, J.J. (2003) Quantum Molecular Dynamics Calculations of Radiative Opacities. A&A, 405, L5-L9.

- 51. http://refractiveindex.info

- 52. Callcot, T.A. and Arakawa, E.T. (1974) Ultraviolet Optical Properties of Li. Journal of the Optical Society of America, 64, 839-845.

https://doi.org/10.1364/JOSA.64.000839 - 53. Mathewson, A.G. and Myers, H.P. (1971) Absolute Values of the Optical Constants of Some Pure Metals. Physica Scripta, 4, 291.

https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-8949/4/6/009