Advances in Applied Sociology

Vol.06 No.02(2016), Article ID:63435,12 pages

10.4236/aasoci.2016.62004

The Jihadist Complex

Ishmael D. Norman1,2

1School of Public Health, University of Health and Allied Sciences (Hohoe Campus), Ho, Ghana

2Institute for Security, Disaster and Emergency Studies, Sandpiper Place, Langma, Ghana

Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 21 December 2015; accepted 13 February 2016; published 16 February 2016

ABSTRACT

Objective: This is an exploratory review of the literature to map out the characteristics of the jihadist complex as a tool for understanding the conduct better than we do now. I assessed the factors leading to youth disenfranchisement to determine whether they were contributory push factors among the youth that are attracted to jihadist causes. What are the modalities for reducing some of the underlying causes of radicalism in the Sub-region and elsewhere? Method: For the theoretical analyses, I relied on five thematic areas theorized by various security researchers that jihadist radicalism is youthful, that it is built on Islamic religious “narrative”, that they are a disenfranchised rebels without a cause, that they are not empathetic towards the suffering of vulnerable Muslims, that due to these antecedents, radicals are “instrumentalized” by groups such as Al Qaeda or ISIS. Result: The result shows the literature on radicalism, jihadist terrorism is still emerging and suffers from the lack of systematic epidemiologic formulation for the analyses of this social conduct. It appears there is confusion among researchers about whether the terrorist suffers from what can be described as “Jihadist Complex”. Discussion: Jihadism is not an esoteric subject that should elude classification with regards to the behaviors of those engaged in this cause, since there is inherent stratification in the social backgrounds that the jihadists come from Africa, Asia, UK or Germany. Conclusion: To address a social challenge, one has to have the capacity to appraise the cause/effect aspect of the challenge on a given person or a group thereof. Jihadist push and pull factors can be understood and classified just as many human conducts are classifiable.

Keywords:

Jihadist Complex, Radicalism, Terrorism, Jihadist, Motivation, Instrumentalized, Al Qaeda, ISIS, West Africa

1. Introduction

It is said that the jihadist does not suffer from any particular neurosis; and that suicide bombers are not crazy. They decide to blow themselves up for a higher purpose. Although the jihadist may not suffer from an identifiable mental illness, the generality of his or her actions appears to invoke a “jihadist complex” (Shultz & Shultz, 2009) . The author borrowed from psychoanalysis “complex” theory as espoused by Jung to explain the proposition. I considered causal agents leading to youth disenfranchisement and disillusionment vis-à-vis radicalism in the West African Sub-region. On record and in recent past, Burkina Faso is the only nation in which the youth have challenged the hegemony of the ruling government by ousting President Blaise Campaore out of office in October 2014. This attempt was in opposition to the President’s intention to expand his reign and rule till 2020. Apart from Burkina Faso, no other nation in the Sub-region has come close to unleashing an “Arab Spring” type of popular uprising. Despite this observation, it can be said that it would be myopic to assume that radicalism has not arrived at the shores of the Gulf of Guinea.

In Psychoanalysis, a “complex” is defined as a core pattern of emotions, memories, perceptions and wishes in the personal unconscious organized around a common theme, such as power or status (Schultz and Schultz, 2009). It assumes that important factors influencing one’s personality are deep in the unconscious. That is to say, complexes influence one’s attitude and behavior. Jung distinguished between two types of complexes in the unconscious mind as: the Personal unconscious and the Collective unconscious (Jung, 1921, 1971) . Whereas the personal unconscious deals with the accumulation of experiences from one’s lifetime that could not be consciously recalled, the collective unconscious, however, was the universal inheritance of human beings (Jung, 1960, 1969) .

It is perhaps, in this zone of unconscious where the “narrative” may morph into psychosomatic experiences for the rookie jihadist or one that pursues a path of self-radicalization.

The “jihadist complex” is, therefore, defined as the feeling of actual or perceived victimization by one or third party against which there ought to be revenge, retaliation, or retribution, which is justified on ideological and religious grounds. The manifestation of the complex is either through self-radicalizing processes or through direct or indirect proselytizing motivated by a fatwa or dawa. Fatwa is that which is sanctioned by Islamic legal opinion. Dawa is a call to Islam to him or her that is “Tablighi Jamaat” or born again. For the youth to begin to feed into the jihadist complex, there are many environmental factors that contribute to the heightening of awareness, the realization of disillusionment, even depression and aggressive, anti-establishment behavior and the subsequent acceptance of the jihadist ideology and mysticism.

There appears to be linkage between the arousal of the jihadist complex and institutional corruption, particularly in relation to the youth. The linkage to institutional corruption is primarily due to its use in the past as justification for military coups in Africa in the era starting from the 1966 coup d’état in Ghana. The same rationale may be used for the recruitment of jihadists.

In other parts of the Sub-region, perceived and real differential vulnerabilities and economic disparities became the raison d’être for coup d’états in the 1980’s and beyond (Norman & Aviisah, 2015) . These underlying economic disparities are still present in many of the nations in the Sub-region and correlate with corruption in the demised countries.

Today, the concern in the Sub-region is not about groups fighting for political independence and autonomy. The struggle, apart from the mundane municipal security and police issues, is also the pre-occupation about terrorism after 9/11 World Trade Center, Pentagon and Pennsylvania bombings in 2001. This development has led almost all of the English Speaking nations in the Sub-region to enact anti-terrorism and anti-money laundering laws in 2008 (Norman et al., 2015; Ibrahim, 2007) .

In a 2008 study conducted by Norman to evaluate the legal framework for emergency preparedness of Accra City against the strength and weakness of the National Disaster Management Organization, (NADMO) it was found that the Ghanaian public considered terrorism as the most significant threat to security. The result showed that about 41% or [103/249] of the respondents rated terrorism as the most overwhelming threat to airport security among others. This is significant in the sense that Ghana has not suffered from direct terrorism activities as we have come to know and understand domestic and international terrorism (Norman, 2008) . This was long before Boko Haram morphed into a militant force in 2009 in Nigeria and in the Sub-region. Boko Haram has international connections to Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, (AQIM) Al Shabaab in East Africa and the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO) as well as ISIS. The official name of Boko Haram is “Jama’atua Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad” or People committed to the Propagation of Prophet Teaching and Jihad (Sageman, 2003) .

In order to demystify the mystic surrounding terrorism as a complicated sub-set of human conduct, we are compelled to consider several pertinent questions raised earlier in this paper but culled and collated from a handful of researchers’ work that: 1) jihadist radicalism is a youth revolt against society, articulated on Islamic religious paradigm, 2) jihadist are not necessarily sympathetic to the suffering in the Muslim communities or the victims of poverty and racism these communities, 3) jihadists are disenfranchised, resentful and suicidal youth with violence-seeking behaviors; 4) jihadists are rebels without a cause but who find “noble” and global justifications for violence in Islamic rhetoric but who are not intellectually or spiritually devoted to Islamic orthodoxy. 5) Due to these antecedents, radicals are subsequently co-opted into; and “instrumentalized” by; dynamic radical groups such as Al Qaeda or ISIS (Roy, 2015; Dickey, 2015; Laqueur, 1997; Wilkinson, 1997) .

As extension of the discussion on jihadist complex, I would approach each salient theme systematically and relate thematic point to the issue of corruption as a correlate to youth unemployment, youth disillusionment, and general feeling of malaise and worthlessness.

First though, it is important to accept that Al Qaeda is the precursor of ISIS. Although ISIS appears to be more aggressive in its thrust for space and followers or fighters, ISIS’s basic philosophy embodies Al Qaeda’s mission and vision: stage terror attacks on behalf of minority Muslims who don’t have the political wherewithal to defend themselves (Ibrahim, 2007) . These are a collective of people who live or are born in deprived enclaves even in the Muslim world and live on the margin in the Western Industrialized nations. They detest the independence and the freedoms their host nation’s citizens enjoy. They detest the technological, ultra-modern world of the Western Industrialized Nations and want to employ any means possible to destroy what the West and other sovereign states that have bought into the western way of life, of business and of politics (Roy, 2015; Sageman, 2003) .

Secondly, it is recognized that terrorism has often been driven by religious or political exigencies. The Zealots and the Sicarii (both of Jewish origins) unleashed the system or rule of terror as a way of scaring, terrorizing people into their own religious faith. They even murdered those who did not succumb to the tenets of their religion. During the French Revolution of 1798 Robespierre was apologetic for terrorism as necessary means to oust those who opposed him. Through the Russian Revolution and the ascendency of the Nihilist and Anarchist movements, terrorism has sought to deliver a message to the world through the “use of violence for political ends, and includes any use of violence for the purpose of putting the public, or any section of the public, in fear” (Williams & Head, 2006; British Government, 1974) .

Another perplexing truism on which many researchers agree about terrorism is that; there is no universal definition of terrorism (Norman et al., 2014) . For example, the United Nations Policy Working Group on Terrorism defines terrorism loosely that, “terrorism is, in most cases, essentially a political act. It is meant to inflict dramatic and deadly injury on civilians and to create an atmosphere of fear, generally for a political or ideological (whether secular or religious) purpose …” (UN Policy Working Group, 2002) . Terrorism is a criminal act (Shawn, 2006) . Other researchers belief it is more than mere criminality. To overcome the problem of terrorism it is necessary to understand its political nature as well as its basic criminality and psychology (Tiefenbrun, 2003) . However, Tiefenbrun (2003) adds that there is no “coordinated position on the meaning of the term” by even the US government or congress. She maintained that the absence of a generally accepted definition of terrorism in the United States allows the government to craft variant or vague definitions which can result in an erosion of civil rights and the possible abuse of power by the state in the name of fighting terrorism and protecting national security. The same charge can be made against all the English speaking nations of West Africa that enacted anti-terror laws in 2008 to fight this social cancer.

Last but not the least, it is important to accept that, researchers have reported that profiling of terrorists is a futile undertaking (Laqueur, 1997; Wilkinson, 1997; Olivier Roy, 2015) . This is because as of yet, research has not isolated a “unique terrorist mindset” ( Dickey, 2015 citing Post, 1985: 103 cited in Dickey, 2015 ). Dickey added that “people who have joined terrorist groups have come from a wide range of cultures, nationalities, and ideological causes, all strata of society, and diverse professions. Their personalities and characteristics are as diverse as those of people in the general population”.

It was precisely for this reason that I propose the jihadist complex as a valid research focus to attempt to unpack the terrorist mystic. If criminal offender types can be classified into their respective units based on the severity or grotesquery of the crime they commit, it is possible to develop the classification or profiling system for the terrorist.

Terrorism is no respecter of gender neither is it gender biased. It is probably one of the few social activities within the Muslim communities where women and men have equal burden of responsibility for action.

2. Method

For the theoretical analyses, I relied on five thematic areas theorized by various security researchers and discussed at some considerable length at the beginning of this paper. The following is the procedure I adopted for the literature review and investigation.

3. Procedure

3.1. Internet Search of Databases

I searched databases such as Pubmed, Medline, Hunari and Google Scholar as well as the Ghana Law Reports for reported cases on radicalism. Editorials and published papers in the English Language were also assessed virtually from the Balme Library and others accessible to the authors. Hand searching of selected printed journals many of which were cited in this paper and the Ghana Annual Security Reports of the Ministry of Interior and others in the overall security affairs of Ghana were conducted to find reported cases of radicalism or jihadist activities.

During the documentary and the internet searches, I used carefully designed phrases like, “radicalism in West Africa, the push and pull factors for jihadists; proselytizing and recruiting of suicide bombers, sympathizers of Boko Haram, sympathizers of ISIS, the West African ‘narrative’ how does it play out?, terrorism, jihadist movement and drive in West Africa.”

3.2. Legislative and Documentary Review

I obtained copies of the important national legislations, such as The 1992 Constitution of Ghana; Banking Act, 2004 (Act 673); Anti-Money Laundering Act, 2008 (Act 749); Anti-Money Laundering (Amendment) Act, 2014 (Act 874); Anti-Terrorism Act, 2008 (Act 762); Economic and Organized Crime Office Act, 2010 (Act 804) This repealed Serious Fraud Office Act, 1993 (Act 466); Economic and Organized Crime Office (Operations) Regulations, 2012 (L.I. 2183); Financial Administration Act, 2003 (Act 654); Narcotics Drugs (Control, Enforcement and Sanctions) Law, 1990 (P.N.D.C.L 236); Insurance Act, 2006 (Act 724); which were available at the Government of Ghana Printers and reviewed them together with case law, policy and other grey literature.

3.3. Criteria for Inclusion

The inclusion criteria of the national legislation on radicalism in Ghana and in the Sub-region and other published papers or regulations were: pertinent papers and documents addressing any or a combination of the basic thematic areas of this paper. Many of such papers and publications were found in other jurisdictions but were adopted for this paper due to their precedecential and probative values. The legislation, paper or document should have had any combination or grouping of any; or all of the following themes: 1) jihadist radicalism is a youth revolt, 2) jihadist are not necessarily sympathetic to the suffering in the Muslim communities, 3) jihadists are disenfranchised and resentful; 4) jihadists are rebels without a cause; 5) Due to these antecedents, radicals are subsequently co-opted into; and “instrumentalized” by; dynamic radical groups such as Al Qaeda or ISIS as advanced by Roy (2015) ; Dickey (2015) ; Laqueur (1997) and Wilkinson (1997) in its establishment sections and subsections, or as part of its topical focus, or be a major theme in the paper or book or report.

All in all, over 100 million documents, papers, links and blogs came up with these search combinations: “terrorism, jihadist movement and drive in West Africa, radicalism in West Africa and the West Africa “narrative”, how does it play out?” Within the West African Sub-region, obtaining copies of cases from court houses is a daunting process since such materials are not easily available to the public or even practicing lawyers from different jurisdictions (Norman et al., 2014) . No reported case was found for this paper. We found a few pertinent grey and published literature on Ghana in relation to terrorism, radicalism and Boko Haram activities but these were not particularly helpful. For this reason, I did not develop an inclusion criterion but used all the materials I could access.

Each of the specific legislation, legislative or executive instrument was read and briefed after a step-by-step and page-by-page investigation to assess how it impacted or affected terrorism, radicalism and youth disenfranchisement. I grouped the documents into their respective units, read them again and selected the ones that dealt with the topics and summarized the findings into their respective units. I interpreted them based upon my education, skills, knowledge in security, law, youth disenfranchisement and conflict.

4. Result

4.1. Jihadist Radicalism Is a Youth Revolt against Society, Articulated on Islamic Religious Paradigm

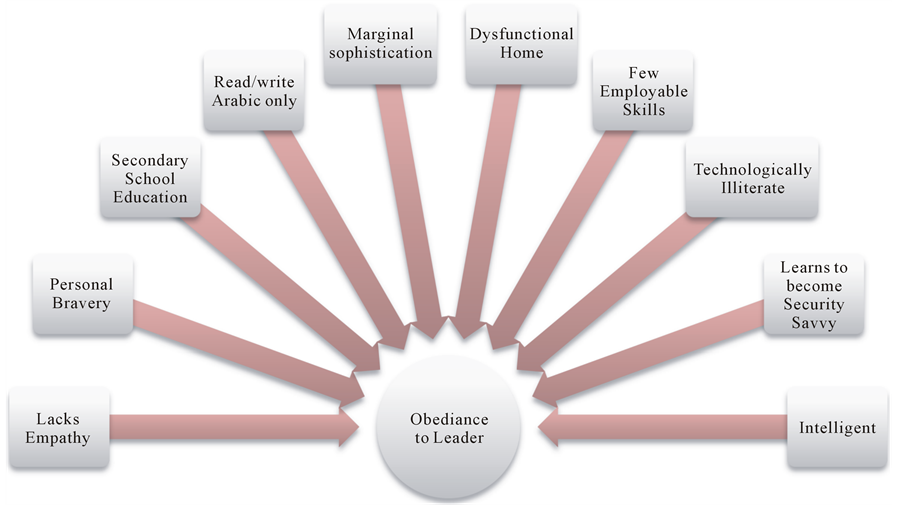

Russell and Miller (1977) provided in their study of eighteen guerrilla groups that the vast majority of the terrorists were single males aged 22 to 24, who may have had some university education or a college degree and tend to be anarchist or have Marxist world view. They advanced the theory that the terrorists that they studied were of urban background and middle class or even upper class. This theory has been refuted by other researchers that while it may describe one group of terrorists from one region, it may not describe all types of terrorist from all regions such as those from Latin America: FARC and Shining Path or from the Middle East: Hamas, Hizbolla, or in West Africa: Boko Haram ( O’Ballance, 1979 cited in Dickey, 2015: p. 4 ). O’Ballance (1979) added that for the terrorist to be successful, he needed certain characteristics such as those shown in the diagram below: Figure 1, Characteristics of a Terrorist.

The leadership of terrorists, just as it is in normal society, tends to be older men who are the theoreticians such Carlos Marighella, Brazil, aged 58 at the time of his death in 11:6:1969. The Palestinian leaderships were in their 40s and 50s (Dickey, 2015) . Whereas the above characteristics may be true of terrorists in the Western and other worlds, in the West Africa Sub-region, during the Liberian civil war, the Rwanda and Burundi genocide and with Boko Haram in Nigeria, the demographics of terrorists in Sub-Saharan Africa in general, showed a predominantly young males aged 14 to 25. These are either inducted or abducted, and may be recruited into the group. The general characteristics would represent that of the general demographics of the population of West Africa, which is very youthful with very common characteristics as shown in Figure 2 with the exception of education. Since groups like the Boko Haram are intrinsically opposed to Western style of education and way of life, the education of its members would be based on Arabic or Islamic model. The name Boko Haram coined by the locals in northern Nigeria, means Western education is forbidden.

Figure 1. Characteristics of a terrorist outside Sub-Saharan Africa.

Figure 2. Characteristics of a terrorist in the West African Sub-region.

4.2. Jihadists Are Not Sympathetic to the Suffering of the Muslim Poor

Roy (2015) is among a growing field of researchers who hold the view that the young jihadist is not sympathetic to the suffering of the disenfranchised Muslims or the economically vulnerable and poor Muslims. The indiscriminate killing of innocent and unarmed civilians by jihadist in Paris in November of 2015, the Bali ‘Paddy Bar and Sari Club bombings, (10: 2002); Madrid Atocha and Santa Eugenia Train Stations bombing, (3: 2004) London Subway and Bus bombing, (7: 2005); Mumbai Railway Massacre, (7: 2006) and other places of recent memory since 9/11, 2001; where Muslims and none Muslims have been murdered shows the depth of disregard for human suffering in general by the jihadist. Each of these attacks was staged as some form of retaliation against a perceived harm or previous injury or detention; and the political oppression of; or discrimination against Muslim minorities (Williams & Head, 2006) .

Roy argued at a recent November 18-19, 2015 Bundeskriminalamt International Conference on terrorism in Germany that:

“The main motivation of young men for joining jihad seems to be the fascination for a narrative: ‘the small brotherhood of super-heroes who avenge the Muslim Ummah’: This ummah is global and abstract, never identified with a national cause (Palestine, or even the Syrian or Iraqi nations). In Iraq the foreign volunteers don’t identify with the local Arab population that they are supposed to support. (This is why they need either imported spouses or sex slaves.) Palestine is not at the core of the mobilization process (Palestinians are mainly supported by progressive people and cultural Muslims, not by the Salafists because it is seen as a ‘profane’ cause).”

Roy went on to provide that the so-called narrative of the young western Salafists is “staged” like an elaborate video game of abstracted villains against whom these young assassins wage jihad to deliver them from distress and from harm. He added that “their radicalization is not the consequence of a long-term ‘maturation’ either in a political movement (Palestine, extreme left, extreme right) or in an Islamic environment. It is on the contrary a relatively sudden individual jump into violence, often after trying something else” such as trying to enlist in their regular respective national armies.

Sageman (2003) gave another dimension to the puzzle at the Third Public Hearing of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States that, the villains in the minds of the Global Salafi Jihad as first proclaimed by Osman bin Laden in his 1996 fatwa is collectively the Western world, but specifically the United States of America. The strategy is to fight the “far enemy”, the West and the U.S. and Israel, before turning to the “near enemy” or despotic monarchs and kingdoms in the Middle East. Sageman, showed that in his study of 130 members of the Global Salafi Jihad, there was no unifying characteristic about them as maintained by Roy (2015) ; O’Ballance (1979) cited in Dickey (2015: p. 4) .

There was also no evidence of comprehensive top-down active recruitment drive in the global jihad. The pressure to join comes from the bottom-up, from the grass-roots, prospective young men eager to commit. Attachment to jihadist movement is selective, preferential entry at the zonal level through nodes, then hubs and finally to the larger group (Roy, 2015; Sageman, 2003; Laqueur, 1997; Wilkinson, 1997) . Sageman also found that “prospective jihadist joined the movement through pre-existing social bonds with people who were already terrorists or had decided to join a group”. This was done through friendship [65% of the new recruits], kinship [15%], with [10%] citing religious beliefs and duty as the reason why they join the Salafist movement, while the rest were through discipleship and worship. Formal invitation to become a jihadist normally occurred after the fact, after the individual was already committed to the cause, and had demonstrated some sort of training in Afghanistan after senior Al Qaeda or ISIS officers have had the chance to evaluate the candidate (Sageman, 2003) .

4.3. Jihadist Is Disenfranchised, Resentful and Suicidal Youth, a Rebel without a Cause

Almost all the researchers and technical field investigators of terrorists affirm that the “narrative” of the jihadist is an abstraction of unexamined realities about how the world works, which are sincerely held by the jihadist. According to Roy (2015) , “the narrative is built using schemes taken from the contemporary youth culture: video-games (Call of Duty, Assassins). It is “staged” (mis en scène) using not only modern techniques, but very contemporary aesthetics, with a special role for the aesthetics of violence, which is also to be found in places with no Islamic reference (“Columbine”, the Mexican Narcos). He says that in such an ecosystem, “two figures are of particular importance: the suicide-bomber and the ‘chevalier’, the first being linked with what Roy calls a ‘generational nihilism’, the second with the video-games. In both cases what is at stake is ‘self-realization’ as an answer to frustration”. What Roy seems to be saying is that the jihadist is blasé about death, because there is no clear line between playing a video game in which villains are blown to pieces and actual suicide bombing in which the perpetrator is dismembered and disarticulated? The Jihadist is detached from the reality of death, the finality of life and has embraced nothingness as a weighty reward.

4.4. “Instrumentalization” of Radicals or Jihadists by Dynamic Groups

Prominent among those arguing the instrumentalizing or weaponizing of jihadists from idealistic killer wanna-be to actual, operationalized killer by dynamic radical groups such as Al Qaeda or ISIS are Roy (2015) and Dickey (2015) . Earlier on in the recent history, Sageman (2003) ; Laqueur (1997) , and Wilkinson (1997) propounded similar affiliations or co-optation by the more powerful groups of the time such as Hamas and Hezbollah. There appears to be confusion in the minds of the researchers about the processes leading to the operationalization of the rookie jihadist. It has previously been argued by the same group of researchers that there is no active top-down recruitment drive by the radical groups and that only about 10% of recruits or Salafists are actually garnered by active, top-down discipleship or worship. If such is the understanding, then instrumentalization of the rookie jihadist only occurs when he or she appears to be self-actualized as a jihadist through training, devotion to ideology and conversion. In other words, turning the jihadist into an instrument of war is only possible when the jihadist self-ascribes as an avenger, Robin Hood of some sort, to right the wrongs against Muslims and Islam proper. That is to say, instrumentalizing occurs to complete a series of processes for self-radicalization initiated by the rookie jihadist. The superior group such as Al Qaeder or ISIS only moves to fulfill the wish of the rookie jihadist into the acceptance of the Salafist philosophy of retributive justice, war and vengeance as an added bonus to the path already chosen.

4.5. Youth Disillusionment in the West African Sub-Region

The Global Salafi Jihad feeds on anti-Western and anti-American hate speech, among others. It emphasizes the corrupting influences of the Western way of life and blames the challenges the youth may be facing in life or at home on government and leadership. I began this paper with the caveat that I would be circumnavigating the contributions of institutional corruption on youth disenfranchisement and disillusionment with radicalism specifically in the West African Sub-region. I offered that the linkage of the analyses to institutional corruption is primarily due to its use in the past as justification for military coups in Africa in the era starting from the 1966 coup d’état in Ghana and how it may be used for recruitment of jihadist. In other parts of the Sub-region, perceived and real differential vulnerabilities and economic disparities became the raison d’être for coup d’états in the 1980’s and beyond (Norman & Aviisah, 2015) . These underlying economic disparities are still present in many of the nations in the Sub-region and may be used as part of the “narrative” to explain the woes facing the Muslim believer in predominantly Christian dominated nation such as Ghana. The “narrative” has been played out in the national politics of nations like Kenya in East Africa between the Muslim enclave of Mombasa and its environs, and the Christian dominated Nairobi and its environs.

Corruption is the bane of African development and youth economic progress. There are few instances of big economic scandal which involved the youth, or those below the age of 45. Many of the larger money scandals running into several millions of dollars almost always involve members of the older adult population aged between 45 and 65 years of age (Norman & Aviisah, 2015) . Across the continent, poor people who use public services are twice as likely as rich people to have paid a bribe, and in urban areas they are even more likely to pay bribes.

Reporting on how Ghana has surpassed Nigeria as the second most corrupt nation in Africa after South Africa, the Chairman of the Transparency International, José Ugaz said, “Corruption has created and increased poverty and exclusion. While corrupt individuals with political power enjoy a lavish life, millions of Africans are deprived of their basic needs like food, health, education, housing, access to clean water and sanitation. We call on governments and judges to stop corruption, eradicate impunity and implement Goal 16 of the Sustainable Development Goals to curb corruption. We also call on the people to demand honesty and transparency, and mobilize against corruption” (Ugaz, 2015) .

In Nigeria, West Africa, this contest is played out between the Muslim north and the Christian south. For example, in Kano, Nigeria, on 13rd November, 2015, deadly clashes erupted between the military and Shiite Muslims in Zaria, northern Nigeria, which also left the group’s headquarters and the home of its leader destroyed. Armed soldiers carried out crackdowns on the pro-Iranian Islamic Movement of Nigeria (IMN) following an incident on the day before involving the convoy of the chief of army staff. The IMN, which seeks to establish an Islamic state through an Iranian-styled revolution, has been at loggerheads with Nigeria’s secular authorities, leading to occasionally violent confrontations. Northern Nigeria is majority Muslim and largely Sunni (Military, Shiite Muslims clash in northern Nigeria: Yahoo News, 2015) .

All the nations in West Africa have youthful populations with the majority of their populations aged 15 to 24 (United Nations World Population Prospects, 2000, 2004, 2006) . In the same report, those aged 15 - 24 would represent 21.8% of the national population with those aged between 15 and 24 representing about 19.6 by the year 2020. This is compared to those aged 60+ with only 7.1% representation and those at 65+ with 4.7% respectively. That is to say 52.9% of Ghana’s population would be under 24 years of age by 2020. In the case of Ghana, Table 1 and Table 2 demonstrate the distribution of the youth in the general population.

Table 1. Proportion of population in selected age groups.

Source: Dept of Statistical Survey, Ghana, 2010 .

Table 2. Shows the summary of the total population aged between 15 and 24 from 2005 through 2030.

Source: United Nations (2008 Revision): Columns 2 and 3 from median variant, pp. 454-455.

Added to the youthfulness of the population, is the issue of teenage and adult unemployment, institutional corruption and abuse of political offices by the various leaderships in the various nations. As was noticed in Burkina Faso recently with the disruption and sacking of the parliament by the youth, the same kinds of conditions exist in just about every other African nation which could lead to a great deal of suffering and disturbances (http://forums.ssrc.org/african-futures/2014/12/09/citizens-revolt-in-burkina-faso). These are all genuine basis for political disequilibrium and re-calibrations of the leadership and policy architecture of a nation so demised.

5. Discussion

Researchers such as Post (1985) cited in Dickey (2015) ; Laqueur (1997) ; Wilkinson (1997) ; and Roy (2015) agree that a “terrorist profile” is misleading. The reasons for this conclusion are that “people who have joined terrorist groups have come from a wide range of cultures, nationalities, and ideological causes, all strata of society, and diverse professions. Their personalities and characteristics are as diverse as those of people in the general population”. I believe the very essence of profiling is based on the diversity and uniqueness of individuals committed to a given social conduct. If terrorists are so unique that they cannot be profiled, then profiling as a craft and a science is dead. There may be sub-types of terrorists no matter how diverse the cohort of terrorist may be, irrespective of cultures, nationalities, ideological causes, and professions, who still may share certain traits and commonalities. It is strange to notice that many researchers actually agree that there is no particular psychological attributes that can be used to describe the terrorist or any “personality” that is distinctive of terrorists. Yet many researchers agree and do report certain cultural and personality traits immediately after a would-be terrorist re-dedicates him/her self to Islam or becomes radicalized, or becomes a jihadist (Roy, 2015) . If serial murderers can be profiled and decoded, then the terrorist who, oftentimes does not even work alone can be profiled and decoded. In a group situation it is possible to miss unique personality traits that may be lost in the mix. If the jihadist is a rebel without a cause but who finds “noble” and global justifications for violence in Islamic rhetoric but who are not intellectually or spiritually devoted to Islamic orthodoxy, then it appears Islam too may suffer some harm from such an association in the short and long run. In the short run, the good name of Islam as a respected world religion is cast by others as a violent religion and Muslims as violent people. Such a reading disparages and demeans Islamic orthodoxy and spirituality. In the long run, Islam may be confronted with a brand of so-called believers who may not hold the tenets of Islam as sacred.

6. Conclusion

The de-coupling of actual jihadist and suicide bomber from the spiritual jihad in Islam may not be an exercise in futility. It might now be the duty of all to help develop the standard of assessment for the “Jihadist Complex” so that we can understand the motivations and the rewards emanating from the Global Salafi Jihad and suicide bombers.

7. Study Limitation

The study did not profit from direct interview with jihadists. I neither conducted an empirical research into the Jihadists movement nor spent time observing jihadist or insurgents at their training or base camp. It is the review of the literature of what other researchers say about the capability of society today to develop an assessment tool for profiling jihadist. I am not an expert in profiling, but like other researchers, have read around the subject of profiling. If this paper has erroneously created the impression that I may be an expert in the subject matter, such is an unexpected outcome and regrettable. This is a purely research product into the subject matter. It arose from the optimism that jihadists like any other group, can be classified. The strength and weaknesses of jihadists are well researched and reported in the scientific literature, particularly since 9/11, 2001. Yet, there appears to be resistance in the security and scientific communities that profiling jihadist is futile, even though most researchers agree that those who participate in extreme violence seem to share quite a number of things in common such as religion, religiosity, the “narrative”, youthfulness, hate for all things western and resentfulness. There appears to be many indicators about who a jihadist could be based upon the historical behavior and mannerism of past jihadists. The research community needs to tease out the lessons learned from each jihadist experiences and story that is available from which we can begin to assimilate those linkages that appear not to be related but which are in fact, related. We need to know that what appears to be unpredictable and random Jihadist activities are not necessarily random or unpredictable; and that within what appears as chaotic and unrelated, exists their relationships and un-randomness (Norman et al., 2015; Lorenz, 1972) .

The real challenge here is not about the difficulty in profiling jihadist, but about the reluctance of researchers in the West to develop a tool for assessment that may be used to deny the civil liberties of many innocent citizens and residents. Despite these observations, the study is still interesting and offers an outlook into the Jihadist Complex and how looking through this lens, we might make other important discoveries about the Jihadists.

Cite this paper

Ishmael D.Norman,11, (2016) The Jihadist Complex. Advances in Applied Sociology,06,36-47. doi: 10.4236/aasoci.2016.62004

References

- 1. British Government (1974).

http://www.terrorism - 2. Department of Statistical Survey (2010). Population in Selected Age Groups 1950-2020, Ghana Census 2010. Accra: Department of Statistical Survey.

- 3. Dickey, C. (2015). Three things Suicide Bombers Have in Common, Newsweek.

http://www.newsweek.com/most-suicide-bombers-have-three-things-common-christopher dickey-79525 - 4. Ibrahim, R. (2007). The Al Qaeda Reader, (Introduction by Victor Davis Hanson) (pp. 1-236). New York: Broadway Books, Doubleday Broadway Publishing Group.

- 5. Jung, C. G. (1969). The Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche. Collected Workds (Vol. 8). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- 6. Jung, C. G. (1971). Psychological Types, Collected Works (Vol. 6). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- 7. Laqueur, W. Z. (1997). Origins of Terrorism: Psychologies, Ideologies, Theologies and States of Mind. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press.

- 8. Lorenz, E. N. (1972). Predictability: Does the Flap of a Butterfly’s Wings in Brazil Set off a Tornado in Texas. Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science.

http://www.chaostheory - 9. Military, Shiite Muslims Clash in Northern Nigeria. (2015).

http://news.yahoo.com/military-shiite-muslims-clash-northern-nigeria-201559877.html - 10. Norman, I. D. (2008). Evaluation of the National Disaster Management Organization’s Preparedness to Deal with Critical National Events. Accra: NADMO Headquarters.

- 11. Norman, I. D., & Aviisah, M. A. (2015). Does Corruption Manifest Post Traumatic Stress Disorder? Donnish Journal of Neuroscience and Behavioral Health, 1, 12-20.

http://donnishjournals.org/djnbh - 12. Norman, I. D., Aikins, M., Binka, F. N., & Awiah, B. (2014). Ghana’s Legal Preparedness against the Perceived Threat of Narcotics Trafficking and Terrorism: A Case Study for West Africa. Issues in Business Management and Economics, 2, 201-209.

- 13. Norman, I. D., Binka, F. N., & Awiah, B. M. (2015). Mapping the Laws on Anti-Money Laundering and Combating Financing Terrorism to Determine Appraisal Skills of Accountable Institutions for the Twin Challenges. Issues in Business Management and Economics, 3, 87-99.

- 14. O’Balance, E. (1979). Islamic Fundamentalist, Terrorism 1979-95: The Iranian Connection. New York: New York University Press.

- 15. Roy, O. (2015). What Is the Driving Force behind Jihadist Terrorism? A Scientific Perspective on the Causes/Circumstances of Joining the Scene. European University Institute in San Domenico, Fiesole/Italy, Speech Delivered at the BKA, Bundeskriminalamt International Conference on Terrorism, 18-19 November 2015.

- 16. Russell, C. A., & Miller, B. H. (1997). Terrorism Profiling Study.

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10576107708435394?journalCode=uter19 - 17. Sageman, M. (2003). The Global Salafi Jihad. Third Public Hearing of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States.

http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/hearings/hearing3/witness_sageman.htm - 18. Shawn, E. (2006). The UN Exposed. New York: Penguin Books Inc.

- 19. Shultz, D., & Shultz, S. (2009). Theories of Personality (9th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

- 20. Tiefenbrun, S. (2003). A Semiotic Approach to a Legal Definition of Terrorism US Department of Defense, 2005, Global War on Terrorism, DOD Needs to Improve Reliability of Cost and Provide Additional Guidelines to Control Cost, GAO-05-882, September 2005.

http://www.pegc.us/archive/Journals/tiefenbrun_terroism_def.pdf - 21. Ugaz, J. (2015). People and Corruption, African Report. Transparency International.

https://www.transparency.org/whatwedo/publication/people_and_corruption_africa_survey_2015 - 22. United Nations Policy Working Group (2002).

http://www.un.org/en/terrorism/pdfs/radicalization.pdf. - 23. United Nations World Population Prospects, The 2000 Revision: Highlights. New York: Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs; 2001. ESA/P/WP.165.

- 24. United Nations World Population Prospects, The 2004 Revision, Volume I: Comprehensive Tables. New York: Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs; 2005. ST/ESA/SER.A/244.

- 25. United Nations World Population Prospects, The 2006 Revision, Volume I: Comprehensive Tables. New York: Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs; 2007.

- 26. Wilkinson, P. (1997). The Media and Terrorism: A Reassessment. Journal of Terrorism and Political Violence, 9, 51-64.

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/09546559708427402

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09546559708427402 - 27. Williams, A., & Head, V. (2006). Terror Attacks: The Violent Expression of Desperation. Futura, Little Brown Book Group, Brettenham House, Lancaster Place, London WC2E 7EN.

Appendix

Whiles this paper was under peer review, the government of Ghana on the 10th of January 2016 informed the citizens of the admission and arrival into Ghana of two former Guantanamo Bay detainees, Mahmud Umar Muhammad Bin Atef and Khalid Mohammad Salif Al-Dhuby. Bin Atef, according to the New York Times Guantanamo Docket, was born in 1979 in Saudi Arabia and fought with Osama Bin Laden’s 55th Arab Brigade and was an admitted member of the Taliban. He was captured in Afghanistan and transferred to U.S. custody about January 2002 after engaging in combat against the American-led coalition.

Like Bin Atef, Salih Al-Dhuby was born in Saudi Arabia and claims Yemeni citizenship, according to the New York Times Guantanamo Docket. The suspected Al-Qaida member was born in 1981 and was captured by Afghan forces in December 2001 following an explosion near Tora Bora. He’s been held in Guantanamo since May 2002.

The government without consultation with the Ghana Parliament, key Ministers of State such as Foreign Affairs, Defence, Interior and many others, accepted the two former detainees to reside in Ghana for two years on humanitarian grounds.

According to the Office of the US Director of National Intelligence, as of January 2014, a total of 104 out of the 614 detainees (17%) released from Guantanamo Bay had engaged in terrorist activities, while another 74 (12%) were suspected of having been involved in terrorist acts.

Needless to say, the national outcry against the admission of the detainees into Ghana is vehement and sustained. This has already degenerated into a Christian versus Muslim ethos, where the Chief Imam’s spokesman has expressed solidarity for the detainees: The National Chief Imam Sheikh Osmanu Nuhu Sharubutu is calling on all Ghanaians to accept the decision by government to bring in two Guantanamo Bay detainees into the country. The position is in sharp contrast with calls by some security experts, civil society groups, and various Christian groups including the Christian Council asking government to return the two detainees. But spokesperson of the Chief Imam, Sheikh Aremeyaw Shaibu told Joy News Ghanaians must help men who have had their human rights violated, re-integrated into society. “From the responses that we got and from the considerations of the Muslim side, we are satisfied by those explanations, and we appreciate the government’s compassion, we appreciate the fairness of government,” (http://www.myjoyonline.com/news/2016/January-14th/lets-accept-the-gitmo-two-chief-imam-pleads.php).

On the other hand, the Christian Council of Ghana, (CCG) has expressed utter disapproval in a statement dated 10 January 2016 and signed by General Secretary Rev. Dr. Kwabena Opuni-Frimpong, that CCG said it has “observed with grave concern the lamentations and fears being expressed by most Ghanaians since news broke about the relocation of two Guantanamo Bay inmates with Al Qaeda ties to Ghana. As a Council, we associate with the uncertainties and fears this issue has generated among our people, and requests that government should consider immediate recession of the decision and relocate the inmates outside the country. The non-engagement of civil society and other stakeholders on such sensitive security issue that affects the common good of the nation has put all of us at risk as the ordinary people don’t know what is required of them in the current potential security threat. In fact, the whole process lacks transparency. “It will be recalled that, in 2007, the United States (US) government wanted to establish its African Command (AFRICOM) in Ghana and most Ghanaians and African countries kicked against it. “The admission of the Guantanamo inmates into Ghana is no different from setting up an AFRICOM in Ghana. “We are of the strongest view that, the inadequate public consultation and broader consensus building by government is exposing our nation and the entire sub-region to terrorist attack, and must be reversed,” (http://www.ghanakasa.com/2016/01/10/send-gitmo-ex-cons-back-christian-council-of-ghana/).