Open Journal of Organ Transplant Surgery

Vol.3 No.3(2013), Article ID:35988,3 pages DOI:10.4236/ojots.2013.33010

Acute Appendicitis Confined to an Incisional Hernia Following Renal Transplantation

Department of Transplant Surgery, University of Illinois, Chicago, USA

Email: shanelbb@uic.edu

Copyright © 2013 Shanel Bhagwandin et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received March 27, 2013; revised April 27, 2013; accepted May 5, 2013

Keywords: Acute Appendicitis; Renal Transplantation; Renal Allograft; Incisional Hernia; Amyand’s Hernia; Hernial Appendicitis

ABSTRACT

We present a case of a 57 years old moderately obese woman with a known 12 cm incisional hernia, who subsequently developed an incarcerated acute appendicitis. The patient underwent an uneventful orthotopic liver and renal transplant five years prior, and was compliant with ongoing immunosuppression without rejection. She presented with 8 hours of acute onset right lower quadrant pain, associated with anorexia, documented fevers, and nausea. Non-contrast CT demonstrated a blind-ending tubular structure with an enhancing and thickened wall within a hernia defect of the right lower quadrant. The patient underwent emergent laparotomy and a non-perforated appendix was completely excised at its base. Discussion: There have been documented reports of an acute appendicitis associated with inguinal hernias, given the eponym Amyand’s hernia. Appendicitis may present within hernias, and there should be a low threshold for radiologic assessment of its components when there is clinical doubt about the symptoms associated with the hernia. Our recommendation prompts early use of non-contrast CT scan in transplant patients with known hernias on examination and abdominal tenderness over the renal allograft considering the high risk of perforation of acute appendicitis and strangulation.

1. Introduction

We present a case report of a 57 years old moderately obese woman with a known 12 cm incisional hernia, who subsequently developed an incarcerated acute appendicitis. The patient underwent an uneventful orthotopic liver and renal transplant secondary to autoimmune hepatitis five years prior to presentation. She had developed a reducible large incisional hernia in her right lower quadrant, overlying her kidney transplant incision. This was initially noted six months after the transplant. She was compliant with her ongoing immunosuppressive regimen of prednisone and tacrolimus. This patient presented with 8 hours of acute onset right lower quadrant pain, associated with anorexia, documented fevers, and nausea. She denied any prior episodes of incarceration or obstructive symptoms.

There have been documented reports of an acute appendicitis associated with inguinal hernias, given the eponym Amyand’s hernia. It remains an uncommon presentation of acute appendicitis with an incidence of 0.13%, and is believed to occur from extra luminal compression of the base of the appendix within the internal ring of the inguinal canal [1,2]. This particular hernial appendicitis has not been described beyond two other cases; however, it proposes complex operative management in consideration of the underlying renal allograft [3,4].

2. Presentation

On examination, her temperature was 39.4˚C, heart rate 98 bpm, and blood pressure 94/66 mmHg. The abdomen was soft, with an obvious firm and irreducible 10 × 10 cm mass extending along the length of her right lower quadrant incision.

There was blotchy non-blanching erythema of the overlying skin. She was in significant discomfort upon compression of the mass, with associated guarding. There were no other suggestions of rebound tenderness or Rovsing’s sign upon palpation of the rest of the abdomen. The remainder of the physical exam was unremarkable.

Laboratory investigations revealed a leukocytosis of 10,000/mm3 with a neutrophil count of 83%. The remainder of her serum lab values was not significant; creatinine was baseline at 1.1. Urinalysis was negative for bacteria and blood.

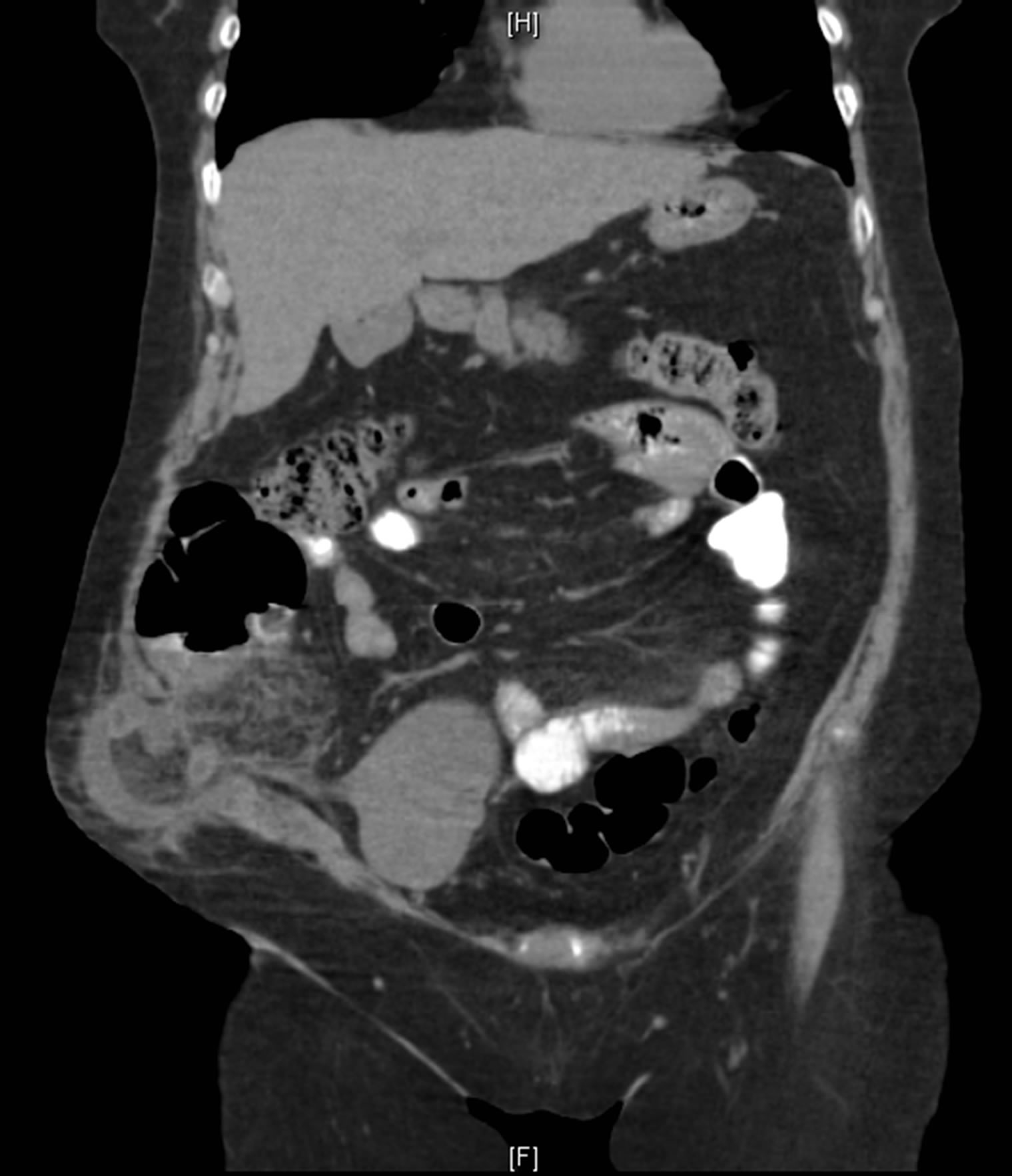

A non-contrast CT was performed that demonstrated a blind-ending tubular structure with enhancing and thickened wall within a hernia defect of the right lower quadrant. The structure was closely related to the cecum, with dilated proximal small bowel loops. A fecalith was noted within the sac at the base of the appendix (see Figures 1(a) and (b)).

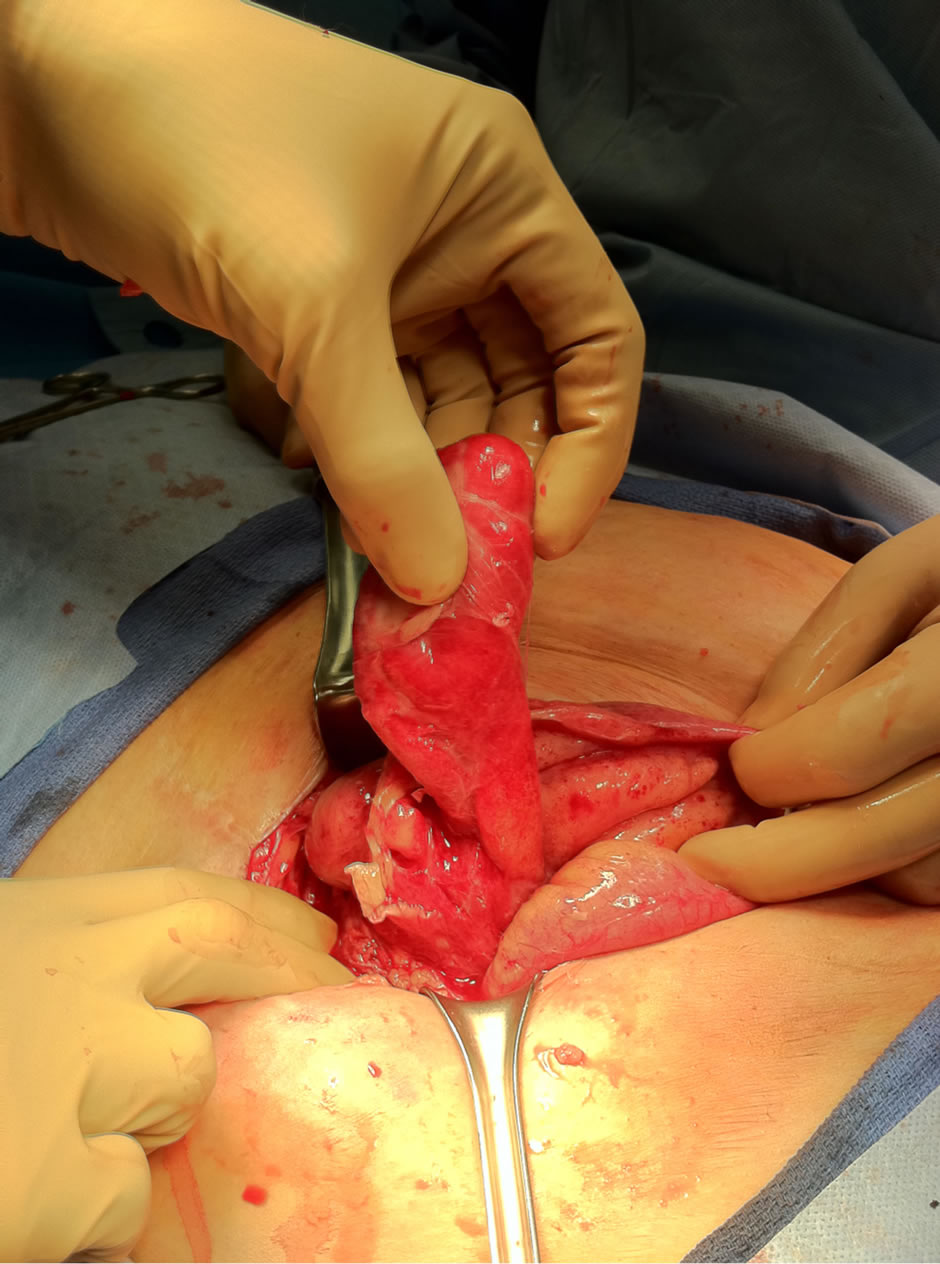

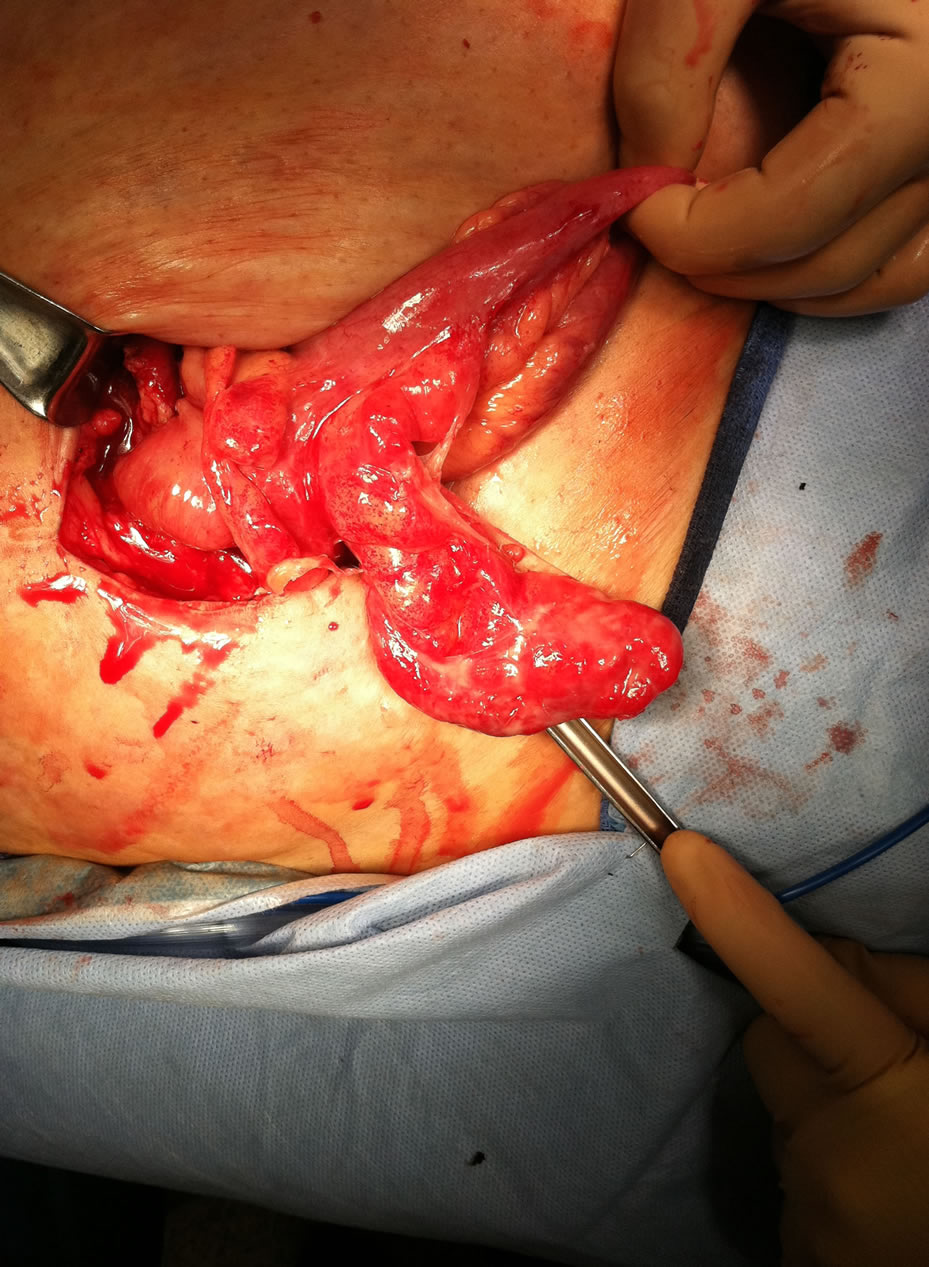

After adequate fluid resuscitation and antibiotic administration, the patient was taken to the operating room. The previous right lower quadrant “hockey-stick” incision was used to enter the peritoneum given its direct access to the appendix and visualization of cecum and small bowel if further resection was warranted. At exploration, an incarcerated acutely inflamed appendix was found within the hernia sac. The appendix was not grossly perforated and did not appear gangrenous; however, upon amputation at the base, the visible mucosa was necrotic (see Figures 2(a) and (b)). A hernioplasty

(a)

(a) (b)

(b)

Figure 1. CT images of incarcerated inflamed appendix within the hernia sac.

(a)

(a) (b)

(b)

Figure 2. Intraoperative images of the inflamed, dilated appendix in situ.

was also performed following appendectomy with primary repair of the defect. There was minimal free fluid within the abdomen, which was copiously irrigated with 2 liters of warm saline prior to closing the abdomen in a standard fashion.

The postoperative course was uncomplicated, and the patient remained afebrile with a progressively declining leukocytosis. Oral intake was resumed on postoperative day 2 with resumption of early bowel activity, and she was discharged home on postoperative day 3 to complete an additional full 1-week course of oral antibiotics.

Histopathologic examination of the specimen showed transmural inflammation of the appendix and periappendicitis. No fecalith was identifited within the specimen.

3. Discussion

Appendicitis may present within hernias, and there should be a low threshold for radiologic assessment of its components when there is clinical doubt about the symptoms associated with the hernia. Despite the presentation of what appeared to be an incarcerated, possibly strangulated hernia, computed tomography (CT) scan was pursued on account of the proximity of the patient’s renal allograft and acute presentation with such a large defect. Tenderness and palpable swelling of the graft is usually associated with pyelonephritis or acute rejection in a patient with concomitant azotemia or oliguria [5]. For an acute appendicitis, the initial presentation is highly variable and can be dependent on the degree of peritoneal contamination as a result of periappendiceal inflammation. The diagnosis of hernial appendicitis is primarily based on a high index of suspicion; however, the primary differential diagnosis remains as an incarcerated or strangulated hernia. Initially, proximal small bowel may not be affected and appear functionally normal, but as the periappendiceal inflammation progresses or as the bowel becomes invested within the hernia sac, it can ultimately become compromised [7-9].

Ultrasound is also another alternative of radiological examination, which can also demonstrate a potential inflammatory mass within the hernia sac and its proximity to other nearby structures, such as the renal allograft in this patient. Although subjective, this is of value to patients who cannot tolerate the oral prep for CT, and where perforation may be imminent if there is further delay [6].

This patient was on a longstanding regimen of immunosuppression and oral prednisone to manage her postoperatively following renal transplantation. The effects of steroids on wound healing are antagonistic to growth factors and collagen deposition that are necessary for adequate incisional strength and contraction. The incidence of developing an incisional hernia is ultimately increased by chronic steroid use in the setting of morbid obesity [5].

Furthermore, given the presence of a fecalith at the base, it’s possible that this case of acute appendicitis may have contained itself within the hernia sac to prevent progression to frank peritonitis. However, incarceration within the sac may have also contributed circumferential pressure at the base with progressive intraluminal obstruction, but this is unlikely given the large defect and acuity of the patient’s presentation.

10 cases of hernial appendicitis published by Carey (1967) failed to preoperatively identify the diagnosis despite sensitive clinical correlation. This was before the utilization of CT scans, as direct X-ray imaging was also not suggestive. Upon direct review of the literature only two cases have been presented in the literature where the diagnosis was established prior to operative intervention and without CT.

4. Conclusion

Our recommendation is that non contrast CT should be pursued in transplant patients with known hernias on examination and abdominal tenderness over the renal allograft considering the high risk of perforation of acute appendicitis and strangulation. This ultimately confirms the diagnosis preoperatively, and allows adequate planning for appendectomy, possible bowel resection, and subsequent hernia repair. Utilization of a non-biological mesh should be avoided given the high incidence of infection, and hernia repair should be delayed if the defect is too large to close primarily.

REFERENCES

- C. Amyand, “Of an Inguinal Rupture, with a Pin in the Appendix Coeci, Incrusted with Stone; and Some Observations on Wounds in the Guts,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, Vol. 39, 1736, p. 329.

- M. T. Logan and J. M. Nottingham, “Amyand’s Hernia: A Case Report of an Incarcerated and Perforated Appendix within an Inguinal Hernia and Review of the Literature,” American Surgeon, Vol. 67, No. 7, 2001, pp. 628- 629.

- Y. Dittmar, H. Scheuerlein, M. Gotz and U. Settmacher, “Adherent Appendix Vermiformis within an Incisional Hernia after Kidney Transplantation Mimicking Acute Appendicitis: Report of a Case,” Hernia, Vol. 16 No. 3, 2012, pp. 359-361. doi:10.1007/s10029-010-0751-3

- C. Sugrue, A. Hogan, I. Robertson, A. Mahmood, W. H. Khan and K .Barry, “Incisional Hernia Appendicitis: A Report of Two Unique Cases and Literature Review,” International Journal of Surgery Case Reports, Vol. 4, No. 3, 2013, pp. 256-258. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2012.12.006

- A. Savar, J. R. Hiatt and R. W. Busuttil, “Acute Appendicitis AfterSolid Organ Transplantation,” Clinical Transplantation, Vol. 20, No. 1, 2006, pp. 78-80. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0012.2005.00444.x

- L. Ash, S. Hatem, G. A. Ramirez and J. Veniero, “Amyand’s Hernia: A Case Report of Prospective CT Diagnosis in the Emergency Department,” Emergency Radiology, Vol. 11, No. 4, 2005, pp. 231-232. doi:10.1007/s10140-005-0411-6

- L. C. Carey, “Acute Appendicitis Occurring in Hernias: A Report of 10 Cases,” Surgery, Vol. 61, No. 2, 1967, pp. 236-238.

- P. G. Horgan, J. O’Donoghue and D. Courtney, “Perforated Appendicitis in an Incisional Hernia,” Irish Journal of Medical Science, Vol. 160, No. 11, 1991, pp. 350-351. doi:10.1007/BF02957893

- H. Sharma, A. Gupta, N. S. Shekhawat, B. Memon and M. A. Memon, “Amyand’s Hernia: A Report of 18 Consecutive Patients Over a 15-Year Period,” Hernia, Vol. 11 No. 1, 2007, pp. 31-35. doi:10.1007/s10029-006-0153-8