Open Journal of Epidemiology

Vol.3 No.2(2013), Article ID:31833,4 pages DOI:10.4236/ojepi.2013.32007

Decreasing serum uric acid levels are associated with improving estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in Japanese women

![]()

1Department of Hygiene, Faculty of Medicine, Kagawa University, Miki, Japan

2Center for Innovative Clinical Medicine, Okayama University Hospital, Okayama, Japan

3Department of Medicine and Clinical Science, Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine, Dentistry and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Okayama, Japan

4Okayama Southern Institute of Health, Okayama Health Foundation, Okayama, Japan

Email: miyarin@med.kagawa-u.ac.jp

Copyright © 2013 Nobuyuki Miyatake et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 1 April 2013; revised 3 May 2013; accepted 11 May 2013

Keywords: Uric Acid; Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR); Lifestyle Modification; Blood Pressure (BP)

ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to investigate the link between changes in a subject’s serum uric acid levels and the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in Japanese women. We used data for 161 Japanese women (49.8 ± 11.7 years) with a 1-year follow up. eGFR was defined by a new equation developed for Japan. eGFR was negatively correlated with serum uric acid levels (r = −0.402, p < 0.0001) at baseline. Subjects were given advice for dietary and lifestyle improvement. At the 1-year follow up, abdominal circumference and systolic blood pressure (SBP) were significantly improved. However, uric acid and eGFR did not change. The changes in eGFR were negatively correlated with uric acid (r = −0.475, p < 0.0001). A decrease in serum uric acid levels was associated with improving eGFR in Japanese women.

1. INTRODUCTION

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) has become a serious problem and is considered as a common disease [1]. About 20% of Japanese population have CKD, which is defined as kidney damage or a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 for at least 3 months regardless of cause [2]. We have also previously showed in a cross-sectional study that the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) [3] in men with abdominal obesity and in women with hypertension was significantly lower than that in subjects without these components of metabolic syndrome [4]. In addition, we also reported that decreasing serum uric acid levels in men was associated with improving eGFR with lifestyle modification with a 1- year follow up [5]. In turn, there are some reports correlated to the association between serum uric acid levels and CKD in foreign countries [6-11]. However, whether decreases in serum uric acid levels with lifestyle modification are beneficial for improving eGFR, and what affects this has on eGFR remains to be evaluated in a longitudinal study in Japanese women.

In this study, we investigated the link between changes in eGFR and changes in serum uric acid levels in Japanese women with a 1-year follow up.

2. SUBJECTS AND METHODS

2.1. Subjects

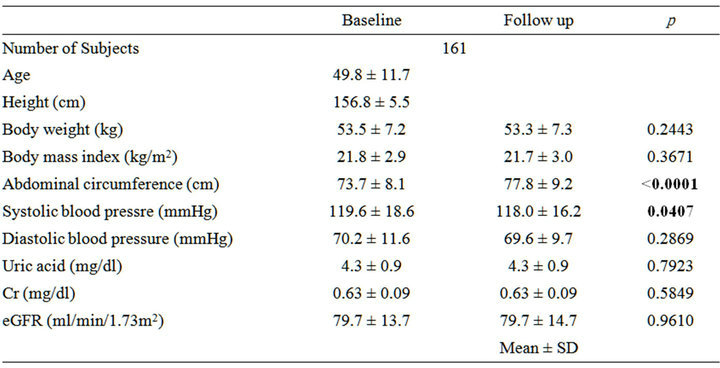

We used data for 161 Japanese women, aged 49.8 ± 11.7 years, who met the following criteria: 1) received a health check-up including special health guidance and a follow-up check-up 1-year later; 2) received anthropometric measurements, fasting blood examination including creatinine, uric acid levels and blood pressure measurements as part of the annual health check-up; 3) received no medications for diabetes, hypertension, and/or dyslipidemia; and 4) provided written informed consent (Table 1).

At the first health check-up, all subjects were given instructions by well-trained medical staff on how to change their lifestyle as special health guidance. Nutritional instruction was provided with a well-trained

Table 1. Clinical characteristics and changes in parameters with 1-year follow up.

nutritionist, who planned a diet for each subject based on their data and provided simple instructions (i.e. not to eat too much and to consider balance when they eat). Exercise instruction was also provided by a well-trained physical therapist, who encouraged each subject to increase their daily amount of steps walked.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethical Committee of Okayama Health Foundation.

2.2. Anthropometric and Body Composition Measurements

Anthropometric and body compositions were evaluated based on the following parameters: height, body weight and abdominal circumference. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by weight/[height]2, in kg/m2. Abdominal circumference was measured at the umbilical level in standing subjects after normal expiration [12].

2.3. Blood Pressure Measurements at Rest

Resting systolic and diastolic blood pressures were measured indirectly using a mercury sphygmomanometer placed on the right arm of the seated participant after at least 15 min of rest.

2.4. Blood Sampling and Assays

We measured overnight fasting serum levels of creatinine (Cr) (enzymatic method) and uric acid. eGFR was calculated using the following equation: eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) = 194 × Cr−1.094 × Age−0.287 × 0.793 [3]. Reduced eGFR was defined as an eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. Serum uric acid levels were measured by the Uricase-Peroxidase method. The institutional normal range was 2.5 - 7.0 mg/dl.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). A statistical analysis was performed using a paired t test: p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated and used to test the significance of the linear relationship among continuous variables.

3. RESULTS

The clinical parameters at the baseline and the 1-year follow up are summarized in Table 1. Abdominal circumference and systolic blood pressure (SBP) were significantly improved with lifestyle modification after one year. However, serum uric acid levels and Cr did not change, and eGFR was also did not change. Nine subjects were diagnosed with reduced eGFR at baseline and ten subjects were diagnosed with reduced eGFR at the 1-year follow up.

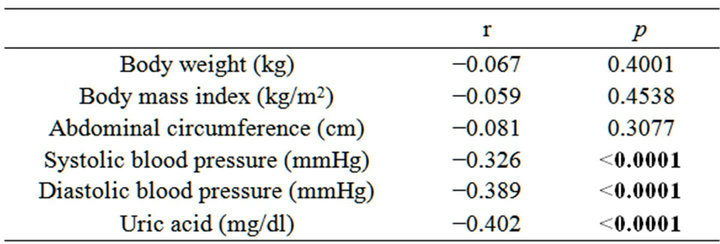

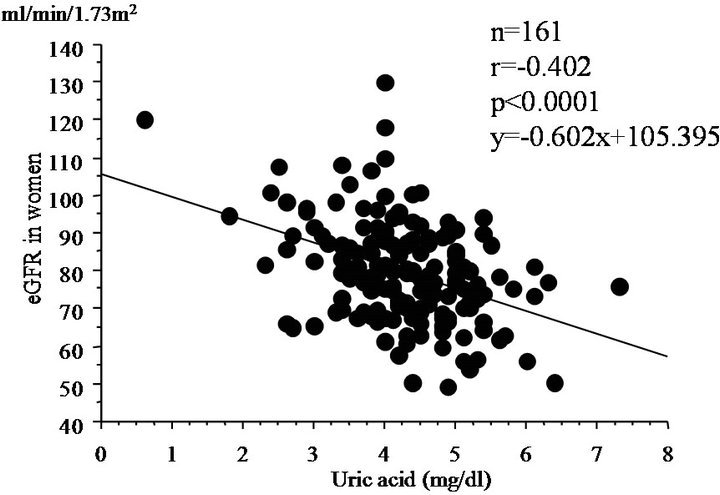

In subjects not taking medications, we also investigate relationship between eGFR and clinical parameters (Table 2). Serum uric acid levels was negatively correlated with eGFR at baseline (r = −402, p < 0.0001) (Figure 1). SBP and diastolic BP (DBP) were also weakly and negatively correlated with eGFR.

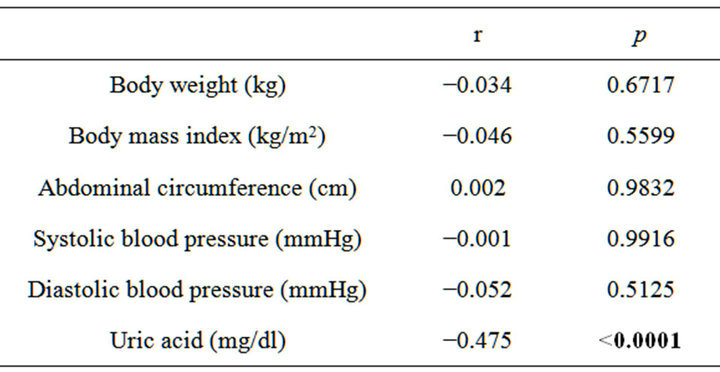

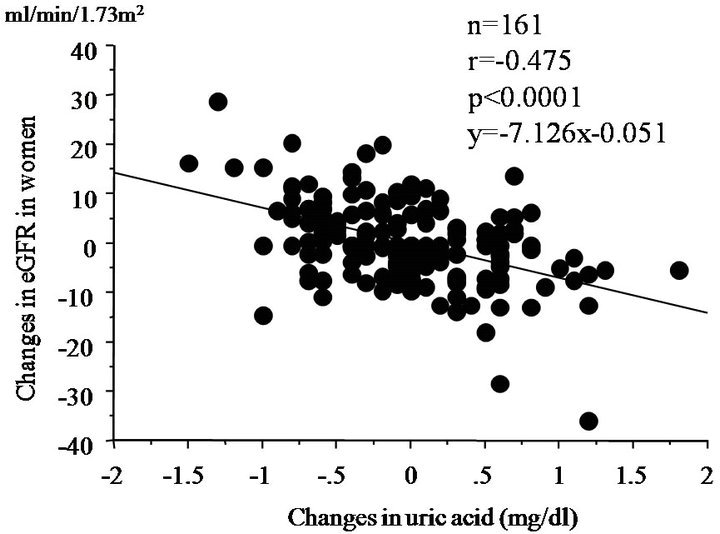

We further evaluated the relationship between changes in eGFR and changes in clinical parameters. Changes in eGFR were negatively correlated with changes in uric acid levels (r = −0475, p < 0.0001) (Table 3 and Figure 2). However, changes in eGFR were not significantly correlated with changes in other parameters.

Table 2. Simple correlation analysis between eGFR and clinical parameters at baseline.

Figure 1. Simple correlation analysis between eGFR and serum uric acid levels at baseline.

Table 3. Simple correlation analysis between changes in eGFR and changes in clinical parameters with 1-year follow up.

Figure 2. Simple correlation analysis between changes in eGFR and changes in serum uric acid levels at 1-year follow up.

4. DISCUSSION

In some literatures [13-15], metabolic syndrome, using the modified ATP III definition [16], was linked to CKD in the Japanese. Compared with subjects with 0 or 1 component of metabolic syndrome, subjects with 2, 3 and 4 or more components showed odds ratios of 1.13, 1.90 and 2.79 for CKD [13]. We have also previously reported in a cross-sectional study that eGFR [3] in men with abdominal obesity and in women with hypertension was significantly lower than that in subjects without these components of metabolic syndrome [4]. In addition, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome was only 3.6% in Japanese women [17]. In our study, with lifestyle modification after the initial health check-up, abdominal circumference and SBP were significantly improved in women without medications at the 1-year follow up. Although eGFR and serum uric acid levels were not significantly improved after one year, changes in eGFR were negatively correlated with changes in serum uric acid levels. Taken together, reducing serum uric acid levels such as medications may be useful for improving eGFR in some Japanese women as noted in Japanese men of our previous study [5].

Higher serum uric acid levels are closely linked to the development of renal injury and end-stage renal disease [6-11]. Yen et al. proved that serum uric acid levels were associated with eGFR and declined in renal function in elderly Taiwanese subjects in a longitudinal analysis [6]. In 5546 Southeast Asian pupulation, higher serum uric acid levels were independently associated with higher prevalence of CKD in a cross-sectional study [7]. Compared with the lowest quartile of serum uric acid (referent), the multivariable odds ratio for quartiles 2-4, respectively, of CKD were 1.53, 2.16 and 4.67 in Appalachian adults [9]. In the Japanese population, hyperuricemia, hypercholesterolemia and diabetes were risk factors for CKD in peripheral arterial disease [18]. Iso et al. reported that eGFR was negatively correlated with the change in serum uric acid [19]. In this study, there was negative relationship between eGFR and serum uric acid levels at baseline. In addition, we found that, changes in serum uric acid levels were correlated with changes in eGFR in women without medications. However, changes in other parameters were not linked to changes in eGFR. Therefore, the clinical impact of serum uric acid levels on eGFR was founded in Japanese women.

Potential limitations remain in our study. First, the small sample size in our study makes it difficult to infer causality between eGFR and serum uric acid levels. In addition, eGFR and serum uric acid levels were not increased with lifestyle modification after one year. Second, we also could not prove the mechanism of the link between eGFR and serum uric acid levels. Third, most of the enrolled women were not diagnosed as CKD at baseline. Therefore, the results in this study may not apply for patients with CKD. Further ongoing studies using medications are required in Japanese women.

5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported in part by Health and Labor Sciences Research Grants from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan.

REFERENCES

- National Kidney Foundation (2002) K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Kidney disease outcome quality initiative. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 39, S1-S266. doi:10.1016/S0272-6386(02)70054-1

- Imai, E., Horio, M., Iseki, K., Yamagata, K., Watanabe, T., Hara, S., Ura, N., Kiyohara, Y., Hirakata, H., Moriyama, T., Ando, Y., Nitta, K., Inaguma, D., Narita, I., Iso, H., Wakai, K., Yasuda, Y., Tsukamoto, Y., Ito, S., Makino, H., Hishida, A. and Matsuo, S. (2007) Prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in the Japanese general population predicted by the MDRD equation modified by a Japanese coefficient. Clinical and Experimental Nephrology, 11, 156-163. doi:10.1007/s10157-007-0463-x

- Matsuo, S., Imai, E., Horio, M., Yasuda, Y., Tomita, K., Nitta, K., Yamagata, K., Tomino, Y., Yokoyama, H. and Hishida, A., on Behalf of the Collaborators Developing the Japanese Equation for Estimated GFR (2009) Revised equations for estimated GFR from serum creatinine in Japan. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 53, 982- 992. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.12.034

- Miyatake, N., Shikata, K., Makino, H. and Numata, T. (2010) Relationship between estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and metabolic syndrome in the Japanese population. Acta Medica Okayama, 64, 203-208.

- Miyatake, N., Shikata, K., Makino, H. and Numata, T. (2010) Decreasing serum uric acid levels might be associated with improving estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in Japanese men. Health, 3, 498-503.

- Yen, C.J., Chiang, C.K., Ho, L.C., Hsu, S.H., Hung, K.Y., Wu, K.D. and Tsai, T.J. (2009) Hyperuricemia associated with rapid renal function decline in elderly Taiwanese subjects. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, 108, 921-928. doi:10.1016/S0929-6646(10)60004-6

- Satirapoj, B., Supasyndh, O., Chaiprasert, A., Ruangkanchanasetr, P., Kanjanakul, I., Phulsuksombuti, D., Utainam, D. and Choovihian, P. (2010) Relationship between serum uric acid levels with chronic kidney disease in a Southeaset Asian population. Nephrology (Carlton), 15, 253-258. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1797.2009.01179.x

- See, L.C., Kuo, C.F., Chang, F.H., Shen, Y.M., Ko, Y.S., Chen, Y.M. and Yu, K.H. (2011) Hyperuricemia and metabolic syndrome: Associations with chronic kidney disease. Clinical Rheumatology, 30, 323-330. doi:10.1007/s10067-010-1461-z

- Cain, L., Shankar, A., Ducatman, A.M. and Steenland, K. (2010) The relationship between serum uric acid and chronic kidney disease among Appalachian adults. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, 25, 3593-3599. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfq262

- Madero, M., Sarnak, M.J., Wang, X., Greene, T., Beck, G.J., Kusek, J.W., Collins, A.J., Levey, A.S. and Menon, V. (2009) Uric acid and long-term outcomes in CKD. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 53, 796-803. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.12.021

- Sturm, G., Kollerits, B., Neyer, U., Ritz, E. and Kronenberg, F. (2008) MMKD Study Group: Uric acid as a risk factor for progression of non-diabetic chronic kidney disease? The Mild to Moderate Kidney Disease (MMKD) Study. Experimental Gerontology, 43, 347-352. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2008.01.006

- Committee to Evaluate Diagnostic Standards for Metabolic Syndrome (2005) Definition and the diagnostic standard for metabolic syndrome. Nippon Naika Gakkai Zasshi, 94, 794-809. (in Japanese)

- Ninomiya, T., Kiyohara, Y., Kubo, M., Yonemoto, K., Tanizaki, Y., Doi, Y., Hirakata, H. and Iida, M. (2006) Metabolic syndrome and CKD in a general Japanese population: The Hisayama Study. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 48, 383-391. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.06.003

- Iseki, K., Kohagura, K., Sakime, A., Iseki, C., Kinjo, K., Ikeyama, Y. and Takishita, S. (2007) Changes in the demographics and prevalence of chronic kidney disease in Okinawa, Japan (1993 to 2003). Hypertension Research, 30, 55-62. doi:10.1291/hypres.30.55

- Tanaka, H., Shiohira, Y., Uezu, Y., Higa, A. and Iseki, K. (2006) Metabolic syndrome and chronic kidney disease in Okinawa, Japan. Kidney International, 69, 369-374. doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5000050

- Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (2001) Executive summary of the third report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel Ⅲ). JAMA, 285, 2486- 2497.

- Miyatake, N., Kawasaki, Y., Nishikawa, H., Takenami, S. and Numata, T. (2006) Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Okayama prefecture, Japan. Internal Medicine, 45, 107-108. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.45.1509

- Endo, M., Kumakura, H., Kanai, H., Araki, Y., Kasama, S., Sumino, H., Ichikawa, S. and Kurabayashi, M. (2010) Prevalence and risk factors for renal artery stenosis and chronic kidney disease in Japanese patients with peripheral arterial disease. Hypertension Research, 33, 911-915. doi:10.1038/hr.2010.93

- Iso, S., Naritomi, H., Ogihara, T., Shimada, K., Shimamoto, K., Tanaka, H. and Yoshiike, N. (2012) Impact of serum uric acid on renal function and cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients treated with losartan. Hypertension Research, 35, 867-873. doi:10.1038/hr.2012.59