Modern Mechanical Engineering

Vol.07 No.01(2017), Article ID:73935,19 pages

10.4236/mme.2017.71002

Coherent Application of a Contact Structure to Formulate Classical Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics

Edwin Knobbe1, Dirk Roekaerts2

1Department of Research Battery Technology, BMW Group, Munich, Germany

2Department Process and Energy, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands

Copyright © 2017 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: September 21, 2016; Accepted: February 3, 2017; Published: February 6, 2017

ABSTRACT

This contribution presents an outline of a new mathematical formulation for Classical Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics (CNET) based on a contact structure in differential geometry. First a non-equilibrium state space is introduced as the third key element besides the first and second law of thermodynamics. This state space provides the mathematical structure to generalize the Gibbs fundamental relation to non-equilibrium thermodynamics. A unique formulation for the second law of thermodynamics is postulated and it showed how the complying concept for non-equilibrium entropy is retrieved. The foundation of this formulation is a physical quantity, which is in non- equilibrium thermodynamics nowhere equal to zero. This is another perspective compared to the inequality, which is used in most other formulations in the literature. Based on this mathematical framework, it is proven that the thermodynamic potential is defined by the Gibbs free energy. The set of conjugated coordinates in the mathematical structure for the Gibbs fundamental relation will be identified for single component, closed systems. Only in the final section of this contribution will the equilibrium constraint be introduced and applied to obtain some familiar formulations for classical (equilibrium) thermodynamics.

Keywords:

Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics, Gibbs Fundamental Relation, Contact Geometry, Second Law of Thermodynamics, Equilibrium Constraint

1. Introduction

The main objective of this paper is to derive a mathematical framework for macroscopic non-equilibrium thermodynamics, which is not based on some kind of an (implicit) equilibrium assumption. Instead it will be shown, that the equilibrium conditions are “contained” in the proposed framework by applying an additional constraint. There are two key components in this innovative derivation: 1) a generalization of Gibbs fundamental relation for non-equilibrium thermodynamics that is based on the dissipation of energy and 2) a unique formulation of the second law of thermodynamics, including a mathematical proper derivation of non-equilibrium entropy as a thermodynamic state function. This paper presents the mathematical framework of Classical Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics (CNET) based on a harmonious integration of mathematics and physics.

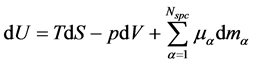

In his monumental work “On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances” [1] Josiah Willard Gibbs (1839-1903) postulates a relation that is fundamental for thermodynamics, viz.

. (1)

. (1)

Gibbs postulates this relation for a mixture of  non-reacting, chemical species in a closed system, which is in a thermodynamic equilibrium state. Often this relation is derived by a simple elimination of the reversible heat flow from both laws of thermodynamics [2] - [7] or it is applied in non-equilibrium states by using the local equilibrium hypothesis [8] . In this paper, only a state space for non-equilibrium thermodynamics will be postulated and the corresponding generalization of the fundamental relation will be derived. This paper will be restricted to closed, single component systems, but a proposition to include the physical phenomena of open systems with chemical reactions can be found in [9] .

non-reacting, chemical species in a closed system, which is in a thermodynamic equilibrium state. Often this relation is derived by a simple elimination of the reversible heat flow from both laws of thermodynamics [2] - [7] or it is applied in non-equilibrium states by using the local equilibrium hypothesis [8] . In this paper, only a state space for non-equilibrium thermodynamics will be postulated and the corresponding generalization of the fundamental relation will be derived. This paper will be restricted to closed, single component systems, but a proposition to include the physical phenomena of open systems with chemical reactions can be found in [9] .

Based on the original work of Rudolf Clausius (1822-1888), the macroscopic entropy of systems in thermodynamic equilibrium is often defined as the quotient of heat flow and temperature. For non-equilibrium processes this definition is then simply extended to an inequality (e.g. Clausius inequality [6] ) or an additional term is included in the definition of macroscopic entropy [10] . The major drawback of these approaches is, that it is not obvious that entropy is also a state function in non-equilibrium thermodynamics. It is often reasoned, that the non-equilibrium entropy has to be a thermodynamic state function. This paper presents a unique postulate for the second law of thermodynamics, which does not explicitly include the concept of entropy. Based on a mathematical property of this postulate, the non-equilibrium entropy will be derived with the appropriate mathematical structure of a thermodynamic state function. This paper is confined to the thermodynamic state space, there is no reference to temporal or spatial coordinates.

Section 2 starts with the introduction of a thermodynamic state and defines a corresponding state function. The mathematical machinery of contact geometry is used to postulate the so-called non-equilibrium state space . Darboux’s theorem can be derived for a contact structure, which possesses the mathematical structure of the Gibbs fundamental relation in thermodynamics (viz. Equation (1)). In the third section the first law of thermodynamics is postulated in such a way, that the internal energy is a state function that complies with the appropriate definition. The next step is to postulate a unique formulation for the second law of thermodynamics and the complying derivation of non-equili- brium entropy. Both sections are combined in Section 4 to identify the thermodynamic potential as Gibbs free energy and to identify the pairs of conjugated coordinates in Darboux’s theorem. With this identification, a generalized Gibbs fundamental relation for non-equilibrium thermodynamics is derived, which includes sufficient additional degrees of freedom to model non-equilibrium phenomena. The postulate for a thermodynamic equilibrium is postponed until the final section of this paper. It will be shown how the equilibrium constraint reduces Gibbs fundamental relation to a Pfaffian equation, which is the basis for the derivation of the so-called Maxwell relations in thermodynamics [3] [5] [6] [7] .

. Darboux’s theorem can be derived for a contact structure, which possesses the mathematical structure of the Gibbs fundamental relation in thermodynamics (viz. Equation (1)). In the third section the first law of thermodynamics is postulated in such a way, that the internal energy is a state function that complies with the appropriate definition. The next step is to postulate a unique formulation for the second law of thermodynamics and the complying derivation of non-equili- brium entropy. Both sections are combined in Section 4 to identify the thermodynamic potential as Gibbs free energy and to identify the pairs of conjugated coordinates in Darboux’s theorem. With this identification, a generalized Gibbs fundamental relation for non-equilibrium thermodynamics is derived, which includes sufficient additional degrees of freedom to model non-equilibrium phenomena. The postulate for a thermodynamic equilibrium is postponed until the final section of this paper. It will be shown how the equilibrium constraint reduces Gibbs fundamental relation to a Pfaffian equation, which is the basis for the derivation of the so-called Maxwell relations in thermodynamics [3] [5] [6] [7] .

2. Non-Equilibrium State Space

A powerful feature of phenomenological thermodynamics is its capability to make statements about the macroscopic state of a system without detailed knowledge of its microscopic details. This feature is based on the phenomenological observation, that a finite number of macroscopic properties is required to completely describe the thermodynamics of a system. Non-equilibrium thermodynamics will be described in a separate state space , which is based on statistical averages of the phase space in statistical mechanics.

, which is based on statistical averages of the phase space in statistical mechanics.

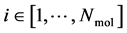

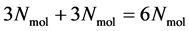

A thermodynamic system consists of  molecules, where each individual molecule

molecules, where each individual molecule  has a position

has a position  and a momentum

and a momentum . The complete set of these

. The complete set of these  positions and

positions and  momenta form the so-called microscopic state of the system. The number of degrees of freedom in this system is, in the case of a 3-dimensional spatial space, equal to

momenta form the so-called microscopic state of the system. The number of degrees of freedom in this system is, in the case of a 3-dimensional spatial space, equal to  (where

(where ). A macroscopic state is a statistical ensemble of this huge amount of microscopic information, where there is a probability distribution over all compatible microscopic states of the system. The corresponding probability density

). A macroscopic state is a statistical ensemble of this huge amount of microscopic information, where there is a probability distribution over all compatible microscopic states of the system. The corresponding probability density  determines the probability that the system will be found in the infinitesimal phase space volume

determines the probability that the system will be found in the infinitesimal phase space volume . It complies with

. It complies with

(2)

(2)

Then the statistical average of some physical observable  can be written as (e.g. see [11] [12] [13] [14] )

can be written as (e.g. see [11] [12] [13] [14] )

(3)

(3)

This equation defines a macroscopic property of a system, which will be applied as a coordinate for the differential manifold  of the thermodynamic state space

of the thermodynamic state space

Non-equilibrium thermodynamics describes changes in a system, which depend on changes in its state

Definition 1 [Non-equilibrium state function]. The 0-form

In this definition symbol

The manifold

Postulate 1 [Gibbs state space]. Non-equilibrium thermodynamics is specified by a

The Gibbs state space

In the general context of this paper, it is very important to notice, that this postulate is neither the first law nor the second law of thermodynamics. The above postulate states that the contact structure

・ it is never equal to zero, so it is either everywhere positive or it is everywhere negative,

・ it is not completely integrable (Frobenius condition).

Both these properties play a key role in the formulation of the second law of thermodynamics in section 3. The physical interpretation of the quantity

According to Darboux’s theorem (see [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] ), there is a set of canonical coordinates

(summation over repeated indices). This equation can be identified as a generalization of the Gibbs fundamental relation, e.g. see Equation (1). Thus, the mathematical structure of the Gibbs fundamental relation is not postulated in this paper. Instead it is derived from a mathematical property of the contact structure

Definition 2 [Thermodynamic potential]. The canonical coordinate

Symbols

3. Thermodynamic Laws

The distinction between exact and inexact 1-forms is an essential part of the mathematical formulation of the first and second laws of thermodynamics. The first law of thermodynamics states that for an arbitrary periodic process, the energy at the start and end of a complete period are identical. This statement complies with the definition of a non-equilibrium state function (e.g. see Definition 1). Both the amount of heat flow

Postulate 2 [First law of thermodynamics]. Summation of the inexact 1-forms for heat flow

The crucial feature in the above postulate is, that the sum of two inexact 1-forms

The internal energy

In nature, it is observed that, for closed systems, processes are such that the system eventually approximates an equilibrium state. Once a system has obtained such an equilibrium state, interactions with the surroundings of the system are required to disturb this equilibrium. Hence, processes are directed towards a mathematical extremum, which corresponds with the equilibrium state, and this is irreversible when there is no interference from outside the system. Observations of these phenomena are for the first time published by Sadi Carnot (1796-1832, see [4] [21] ) and later mathematically formulated by Rudolf Clausius (see [22] [23] ). Clausius postulates, that a system in an equilibrium state has a macroscopic property, which he calls entropy

As is already stated before, the heat flow

Table 1. Overview of the Frobenius integrability condition (e.g. see [18] [24] [25] ).

in Postulate 2. In classical thermodynamics, the above definition is then often extended to non-equilibrium states by replacing the equal sign with an unequal sign or by adding some other term3. In such an approach, it is not clear that entropy

In these relations

One of the less famous pioneers in thermodynamics is the Greek mathematician Constantin Carathéodory (1800-1900). His work [30] [32] [33] on the use of Pfaffian equations for the mathematical formulation of thermodynamics has been crucified4, although it is one of the first attempts for a rigorous formalization of thermodynamics. In the second axiom in his 1909 paper [31] , he has an interesting formulation for the second law of thermodynamics that is based on geometrical considerations:

Axiom II: In jeder beliebigen Umgebung eines willkürlich vorgeschriebenen Anfangszustandes gibt es Zustände, die durch adiabatische Zustandsänderungen nicht beliebig approximiert werden können5.

Above axiom is in the literature also known as Carathéodory’s inaccessibility condition or as Carathéodory’s principle [30] . Notice that Carathéodory makes a statement about an arbitrary initial state, so in this axiom there is no explicit restriction to a thermodynamic equilibrium. But in his paper an adiabatic process is defined as a process where the systems remain in (phase) equilibrium when the deformable coordinates change6. So the heat transfer is not necessarily always equal to zero, which is in the textbook of Bamberg and Sternberg [13] [24] elegantly formulated by the mathematical concept of a null curve

Based on the Frobenius integration theorem the second relation is derived from Axiom II and therefore also known as Carathéodory’s theorem [24] [35] [36] .

So modern interpretations of mathematical formulations for the definition of entropy in classical thermodynamics show, that the Frobenius integration theorem plays a crucial role. But opposite to the before mentioned formulations, in this paper Frobenius integration theorem is not applied to the inexact 1-form

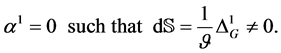

Postulate 3 [Second law of thermodynamics]. The difference between the inexact 1-form

Similar to the approach of Carathéodory, the concept of entropy is not defined in the above formulation for the second law of thermodynamics. Based on the integrability condition in Postulate 3 it can then be shown (see [18] [37] ), that there exists exactly one pair of conjugated coordinates. Here these coordinates are denoted by the absolute temperature

The exterior derivative of entropy

An integral part of the definition of a non-equilibrium state function is, that the initial value is identical to the final value at the end of a complete period in a periodic process. This means that the initial and final non-equilibrium state

Both the absolute temperature

4. Identification of Thermodynamic Coordinates

In this section the thermodynamic potential

This equation does not add new information to the presented mathematical framework of non-equilibrium thermodynamics. It only specifies the set of coordinates that determines the work flow

By comparing this equation with Equation (6), one could argue that the thermodynamic potential and the set of conjugated coordinates are identified. But this identification would not be a sound mathematical proof due to the presence of the contact 1-form

Opposite to most textbooks on thermodynamics, in this paper the definition of the Gibbs free energy

Theorem 1 [Gibbs free energy]. For a single component, closed system the thermodynamic potential

The corresponding pairs of conjugated coordinates

Proof. The proof starts with the combination of the generalized Gibbs fundamental relation and the second law of thermodynamics by substituting Equation (13) into Equation (6). Then replace the 1-form

Notice that due to these steps the Gibbs contact 1-form

The next step in this proof is based on a unique property of thermodynamic properties: thermodynamic properties are either extensive or intensive quantities. Extensive quantities are proportional to the size (or extend) of the thermodynamic system and therefore scalable, while intensive quantities are independent of the size of the system. The total volume

Consider the case that all conjugate coordinates denoted by

The total volume

and

Equation (23)2 is obtained by multiplying Equation (23)1 with the total volume

The final step in this proof is to identify the set of conjugated coordinates

This is again a Pfaffian equation for a thermodynamic state function, either for the Gibbs energy

There are

Again, for an arbitrary thermodynamic process the above equation can only hold when all terms between brackets are equal to zero. The set of extensive conjugated coordinates

Equation (17), which is in this paper derived in the above proof, is in the literature also known as Euler’s relation (e.g. see [38] [39] [40] ). Substitute Equation (17) and the pairs of conjugated coordinates in Theorem 1 into Equation (6) to obtain the following generalized formulation for the Gibbs fundamental relation

Equation (16) can be derived by subtracting the above equation from Equation (27), where

Both Equations (16) and (27) are implementations of Equation (6) for single component, closed systems, which is therefore a generic formulation of the third key element of thermodynamics (besides both laws of thermodynamics). Both equations confirm that Gibbs free energy

5. Equilibrium Constraint

So far, this paper has been focused on the general case of non-equilibrium states and arbitrary irreversible processes. For an isolated system (then there are no interactions with the surroundings), it is in nature observed, that the macro- scopic state of the system does not change any more if one waits sufficiently long. The corresponding thermodynamic state is called the equilibrium state of the system for which the change of a state function

Molecules do not stop moving in such an equilibrium state; there are many fluctuations of the microstates, which are not visible on the macroscopic level. On a macroscopic level, any perturbation away of an equilibrium state requires some kind of exchange with the surrounding of the system. The above equation implements a mathematical extremum, which is not present in the proposed mathematical framework for non-equilibrium thermodynamics due to the mathematical properties of the Gibbs contact 1-form

The absolute temperature

Based on the above considerations it becomes clear, that an additional mathematical construct is required to embed equilibrium thermodynamics within the proposed mathematical framework. Consider therefore an arbitrary irreversible process

Postulate 4 [Equilibrium constraint]. There exists an equilibrium map

This postulate can also be found in the original work of Hermann [15] and Mrugała [44] on thermodynamics in a geometric framework. The modern literature (e.g. see [15] [16] [43] [44] [45] [46] ) uses the Legendre manifold

The distinction between the equilibrium Legendre state space

Next some results will be obtained for the case of equilibrium thermodynamics. An underline will be used in this paper to denote symbols that refer to an

Figure 1. Geometric visualization of the Legendre state space

equilibrium state on the Legendre submanifold

Then a similar procedure can be applied to pairs of conjugated coordinates in Equation (6), where the 1-form

Thus, application of the equilibrium map in Postulate 4 to the generalized Gibbs fundamental relation in Equation (6) results in

The last relation is called a Pfaffian equation, where the 1-form

The relations in Equation (35)3 follow from the combination of Equations (34)2 and (35)2, so these relations are only valid for equilibrium thermodynamics. To further clarify this point, consider internal energy

Since the Gibbs contact 1-form

Another example of interesting formulations in equilibrium thermodynamics are the so-called Maxwell relations (e.g. see [3] [7] [48] ). Apply the equilibrium constraint in Postulate 4 to Equation (16), which reduces to the following Pfaffian equation on the Legendre submanifold

The second relation shows the correct set of canonical coordinates to completely specify internal energy

Mixed derivatives that originate from a closed 1-form are symmetric11. So, differentiate the first relation with respect to volume

Based on the Poincaré lemma, it can be proven that every exact 1-form is also a closed 1-form (see [17] [25] ). Hence

The term between parentheses has to vanish since

This is one of the familiar four Maxwell relations [3] [5] [6] [7] [48] , where it is shown in this paper that they can be derived only for the case of equilibrium thermodynamics. Finally, apply the pull-back of map

So, the thermodynamic potential (viz. here

6. Conclusions

Classical Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics (CNET) is the science of phenomenological changes in the state of systems. Especially these changes make the tools of differential geometry extremely suited for a rigorous mathematical formulation. The presented formulation for non-equilibrium thermodynamics consists of the following three base postulates:

・ there exists a non-equilibrium thermodynamic phase space (Gibbs state space),

・ energy is conserved (first law of thermodynamics),

・ the difference between heat flow and dissipation is completely integrable (second law of thermodynamics).

The thermodynamic phase space is built upon macroscopic properties of a system. Neither temporal nor spatial coordinates are considered in the presented mathematical formulation of non-equilibrium thermodynamics. The direction of processes is not implemented by an explicit inequality in the second law of thermodynamics. Instead an implicit reverse is applied: there is a physical quantity that is nowhere equal to zero, viz. the dissipation of energy. Furthermore, no explicit signs are assigned to nowhere vanishing physical quantities. Still this formulation shows clearly that there can only be a periodic process if and only if it is driven by the appropriate heat flow.

Together with the definition of a state function, other relations are derived based on the mathematical properties of this formulation. The mathematical structure for the Gibbs fundamental relation follows from the Gibbs state space. Through a clever combination with both laws of thermodynamics it can be proven that the thermodynamic potential is specified by the Gibbs free energy. Other coordinates in the formulation of the Gibbs fundamental relation are identified for a single component, closed system. Notice that there is neither in the postulates, nor in the derivation of the mathematical framework for non- equilibrium thermodynamics any assumption that restricts the arbitrary processes to certain classes (e.g. periodic, adiabatic, sufficiently slow, etc.).

The introduction of an equilibrium state is postponed until the final section, where it is introduced as an extremum (viz. no change of a state function). This is mathematically implemented by the pull-back of an equilibrium map with the condition that there is no dissipation of energy. Such an elaborate construction is required, because the dissipation of energy is in the general case of non- equilibrium thermodynamics by definition unequal to zero. For the case of an equilibrium state, the Gibbs fundamental relation reduces to a Pfaffian equation. It is shown that the Maxwell relations in thermodynamics can be derived only for the case of an equilibrium state.

Cite this paper

Knobbe, E. and Roekaerts, D. (2017) Coherent Application of a Contact Structure to Formulate Classical Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics. Modern Mechanical Engineering, 7, 8-26. https://doi.org/10.4236/mme.2017.71002

References

- 1. Gibbs, J.W. (1928) On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances. In: Collected Works, Volume I: Thermodynamics, Chapter III, Longmans, Green, New York, 55-353. (Originally published in Transactions of the Connecticut Academy, III, pp. 108-248, 1876, and pp. 343-524, 1878).

- 2. Haupt, P. (2002) Continuum Mechanics and Theory of Materials. 2nd Edition, Springer, Berlin.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-04775-0 - 3. Moran, M.J. and Shapiro, H.N. (1998) Fundamentals of Engineering Thermodynamics. 3rd Edition, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester.

- 4. Müller, I. (2007) A History of Thermodynamics: The Doctrine of Energy and Entropy. Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

- 5. Nickel, U. (2011) Lehrbuchder Thermodynamik: Einverstandliche Einfuhrung. 2. Auflage Edition, PhysChemVerlag, Erlangen. (In German)

- 6. Nolting, W. (2012) Grundkurs Theoretische Physik 4: Spezielle Relativitatstheorie, Thermodynamik. 8. Auflage Edition, Springer-Verlag, Berlin. (In German)

- 7. Smith, J.M., Van Ness, H.C. and Abbott, M.M. (2005) Introduction to Chemical Engineering Thermodynamics. 7th International Edition, McGraw-Hill Chemical Engineering Series. McGraw-Hill, Boston.

- 8. Kjelstrup, S. and Bedeaux, D. (2008) Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics of Heterogeneous Systems. Series on Advances in Statistical Mechanics (Vol. 16), World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd, Singapore.

https://doi.org/10.1142/6672 - 9. Knobbe, E.M. (2010) On the Integration of the Arbitrary Lagrangian-Eulerian Concept and Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics. PhD Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft.

- 10. Kondepudi, D. and Prigogine, I. (1998) Modern Thermodynamics: From Heat Engine to Dissipative Structure. John Wiley & Sons, Chicester.

- 11. Attard, P. (2012) Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics and Statistical Mechanics: Foundations and Applications. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199662760.001.0001 - 12. Olla, P. (2015) An Introduction to Thermodynamics and Statistical Physics. UNITEXT for Physics. Springer International Publishing, Cham.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-06188-7 - 13. Scheck, F. (2008) Theoretische Physik: Statistische Theorie der Warmeleitungstheorie. Springer-Verlag, Berlin. (In German)

- 14. Zorich, V. (2011) Mathematical Analysis of Problems in the Natural Sciences. Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-14813-2 - 15. Hermann, R. (1973) Geometry, Physics, and Systems. Pure and Applied Mathematics. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York.

- 16. Arnol’d, V.I. (1989) Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics. Vol. 60, 2nd Edition, Springer-Verlag, New York.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-2063-1 - 17. McInerney, A. (2013) First Steps in Differential Geometry: Riemannian, Contact, Symplectic. Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics. Springer Science + Business, Media.

- 18. Edelen, D.G.B. (1985) Applied Exterior Calculus. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York.

- 19. Kushner, A., Lychagin, V. and Rubtsov, V. (2007) Contact Geometry and Nonlinear Differential Equations. Volume 101 of Encyclopedia of Mathematics and It’s Applications, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- 20. Lang, S. (2002) Introduction to Differentiable Manifolds. Universitext. 2nd Edition, Springer, New York.

- 21. Mendoza (1988) Reflections on the Motive Power of Fire. Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola.

- 22. Clausius, R.J.E. (1854) Uebereineveranderte Form des zweitenHauptsatzes der mechanischen Warmetheorie. Annalen der Physik und Chemie, 169, 481-506. (In German)

- 23. Clausius, R.J.E. (1865) Ueberverschiedenefür die Anwendungenbequeme Formen der Hauptgleichungen der mechanischen Warmetheorie. Poggendorff’s Annalen der Physik, 125, 353-400. (In German)

- 24. Bamberg, P.G. and Sternberg, S. (1990) A Course in Mathematics for Students of Physics. Volume 2, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- 25. Frankel, T. (2004) The Geometry of Physics: An Introduction. 2nd Edition, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- 26. Szekeres, P. (2004) A Course in Modern Mathematical Physics: Groups, Hilbert Space and Differential Geometry. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511607066 - 27. Eu, B.C. (1995) Form of Uncompensated Heat Giving Rise to a Pfaffan Differential Form in Thermodynamic Space. Physical Review E, 51, 768-771.

- 28. Eu, B.C. (1999) Generalized Thermodynamics of Global Irreversible Processes in a Finite Macroscopic System. Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 103, 8583-8594.

- 29. Eu, B.C. (2004) Generalized Hydrodynamics in the Transient Regime and Irreversible Thermodynamics. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, 362, 1553-1565.

https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2004.1404 - 30. Born, M. (1921) Kritische Betrachtungen zur traditionellen Darstellung der Thermodynamik. Physikzeitschrift, 22, 218-224, 249-254, 282-286. (In German)

- 31. Carathéodory, C. (1909) Untersuchungenüber die Grundlagen der Thermodynamik. Mathematische Annalen, 67, 355-386. (In German)

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01450409 - 32. Caratheodory, C. (1925) Uber die Bestimmung der Energie und der absoluten Temperature mitHilfe von reversible Prozessen. Sitzungsberichte der Praußischen Akademie der Wissenschaftenzum, Berlin, 39-47. (In German)

- 33. Pogliani, L. and Berberan-Santos, M.N. (2000) Constantin Carathéodory and the Axiomatic Thermodynamics. Journal of Mathematical Chemistry, 28, 313-324.

- 34. Truesdell, C. (1984) Rational Thermodynamics. 2nd Edition, Springer, New York.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-5206-1 - 35. Uffink, J. (2001) Bluff Your Way in the Second Law of Thermodynamics. Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 32B, 305-394.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1355-2198(01)00016-8 - 36. Uffink, J. (2003) Entropy, Chapter 7: Irreversibility and the Second Law of Thermodynamics. Princeton Series in Applied Mathematics, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 121-146.

- 37. Salamon, P., Andresen, B., Nulton, J.D. and Konopka, A.K. (2006) Systems Biology: Principles, Methods and Concepts, Chapter 9: The Mathematical Structure of Thermodynamics. CRC Press, Boca Raton, 207-221.

- 38. Lebon, G., Jou, D. and Casas-V’azquez, J. (2008) Understanding Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics: Foundations, Applications, Frontiers. Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-74252-4 - 39. Reichl, L.E. (2009) A Modern Course in Statistical Physics. 3rd Revised and Updated Edition, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim.

- 40. Shell, M.S. (2015) Thermodynamics and Statistical Mechanics: An Integrated Approach. Cambridge University Press, Santa Barbara.

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139028875 - 41. Haslach Jr., H.W. (1997) Geometric Structure of the Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics of Homogeneous Systems. Reports on Mathematical Physics, 39, 147-162.

- 42. Mrugala, R. (1993) Continuous Contact Transformations in Thermodynamics. Reports on Mathematical Physics, 33, 149-154.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0034-4877(93)90050-O - 43. Mrugala, R., Nulton, J.D., Schon, J.C. and Salamon, P. (1991) Contact Structure in Thermodynamic Theory. Reports on Mathematical Physics, 29, 109-121.

- 44. Mrugala, R. (1978) Geometrical Formulation of Equilibrium Phenomenological Thermodynamics. Reports on Mathematical Physics, 14, 419-427.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0034-4877(78)90010-1 - 45. Mrugala, R. (1985) Submanifold in the Thermodynamic Phase Space. Reports on Mathematical Physics, 21, 197-203.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0034-4877(85)90059-X - 46. Mrugala, R., Nulton, J.D., Schön, J.C. and Salamon, P. (1990) Statistical Approach to the Geometric Structure of Thermodynamics. Physical Review A, 41, 3156-3160.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.41.3156 - 47. Tu, L.W. (2008) An Introduction to Manifolds. Universitext. Springer Science + Business Media, LLC, New York.

- 48. Kluge, G. and Neugebauer, G. (1994) Grundlagen der Thermodynamik. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg. (In German).

- 49. Abraham, R., Marsden, J.E. and Ratiu, T. (1988) Manifolds, Tensor Analysis, and Applications. 2nd Edition, Vol. 75, Springer-Verlag, New York.

- 50. Flanders, H. (1963) Differential Forms with Applications to the Physical Sciences. Vol. 11, Academic Press, New York.

- 51. Lang, C.B. and Pucker, N. (2005) Mathematische Methoden in der Physik. 2nd Edition, Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, München. (In German)

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-8274-3125-7

NOTES

1The macroscopic property has obtained an identical statistically averaged value compared to its initial value, but this does not mean that the probability distribution is identical to its original distribution (nor that the microstates are identical). This observation is a severe release of constraints compared to traditional equilibrium based approaches.

2Here the concepts and notation of this paper are used, where an equilibrium state is denoted by underlined symbols (see also Section 5).

3In this context is the work of Eu [27] [28] [29] very interesting. He is aware that the Clausius definition for entropy holds only for reversible processes (e.g. equilibrium state). Eu introduces therefore a new thermodynamic quantity Calortropy

4See the Appendix to the Historical Indroit: Failure of Carathéodory’s attempt to set the house in order’ in the textbook on Rational thermodynamics by Truesdell (pp. 49-57 in [34] ).

5In every neighborhood of an arbitrary thermodynamic state there exist states that cannot be approached by an adiabatic process.

6Based on three assumption he introduces a simple system together with a quasi-static change of state, which is in his formulation another reference to an equilibrium state.

7Examples are: elastic deformation

8In principle the following derivation is independent of which of the conjugated coordinates is extensive or intensive, as long as every pair contains of an extensive and an intensive quantity. But it is exactly this particular case, which will reveal that the thermodynamic potential

9Quote from [44] , but modified with the conventions of this paper.

10It is here tacitly assumed that

11Definition 1 introduced the non-equilibrium state function as an exact 1-form and Equation (34)1 shows that the 1-form