Open Journal of Polymer Chemistry

Vol.07 No.04(2017), Article ID:80744,16 pages

10.4236/ojpchem.2017.74006

Highly Branched Poly(α-Methylene-γ-Butyrolactone) from Ring-Opening Homopolymerization

Pascal Binda*, Zakiya Barnes, Dechristian Guthrie, Rasaan Ford

Department of Chemistry and Forensic Science, Savannah State University, Savannah, GA, USA

Copyright © 2017 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: October 12, 2017; Accepted: November 27, 2017; Published: November 30, 2017

ABSTRACT

New heteroleptic lanthanide complex [L1ILaN{Si(CH3)2}] (1) containing tridentate [ONO] ancillary ligand was synthesized from an acid-base ligand exchange reaction with ligands H2L1 and corresponding homoleptic lanthanide compound La[N{Si(CH3)3}2]3. Meanwhile, dimeric complexes [L1LaCl] (2) and [L1ILaCl] (3) were prepared from salt metathesis reaction between one equivalent of ligands H2LI,II, three equivalent of NaN{Si(CH3)3}2, and one equivalent of LaCl3. These compounds were characterized by nuclear magnetic resonance (300 MHz) and elemental analysis. These complexes were used as catalysts in the ring-opening homopolymerization of α-methylene-γ-butyrolactone. While compound 1 did not show any significant reactivity, compounds 2 and 3 gave significant amount of highly branched poly(α-methylene-γ-butyrolactone) as confirmed by 1H NMR spectroscopy and Malvern’s triple detector GPCMax analysis in DMSO with molecular weights of over 500,000 Dalton. The glass-transition temperatures of the branched polymer samples were determined using a Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer, DMA Q800.

Keywords:

Lanthanide, α-Methylene-γ-Butyrolactone, Polyesters, Ring-Opening Polymerization

1. Introduction

Due to their good mechanical properties, hydrolyzability and biocompatibility, aliphatic saturated polyesters have been extensively investigated with great applications in packaging, drug delivery and medical implantation devices [1] - [10] .

The best and most reliable method of synthesizing high molecular weight polyesters is via ring-opening polymerization (ROP) of lactones with a relatively high strain energy using metal initiators for chain-growth polymerization [11] - [35] .

Unsaturated polyesters are of high scientific and technological interest for producing tailor-made functionalized biodegradable materials of commercial importance [36] [37] [38] . Preferably, they are easily synthesized via ring-opening polymerization (ROP) of unsaturated lactones [38] . α-Methylene-γ-butyrolactone (α-MBL), also known as Tulipaline A, has received much interest in the synthesis of sustainable unsaturated polyesters since it is the simplest member of a class of naturally occurring sesquiterpene lactones found in tulips [37] - [46] . α-MBL can also be produced chemically from biomass feed stocks making it naturally renewable [47] . When polymerized, α-MBL can either undergo vinyl addition polymerization at the highly reactive exocyclic double bond or ROP of the γ-butyrolactone (γ-BL) five-membered ring (Scheme 1). γ-BL is non-polymerizable due to its low strain energy [48] [49] [50] [51] .

Because vinyl-addition is favored over ring-opening at room temperature due to the stability of five membered rings, special conditions and reagents must be used to favor the ring-opening polymerization. In fact, ring-opening copolymerization of α-MBL and other highly strained lactones to obtain unsaturated polyesters have been reported [39] [42] [46] . However, the ring-opening homopolymerization of α-MBL has not been reported in the literature. Herein, we report the ring-opening homopolymerization of α-methylene-γ-butyrolactone into highly branched polyester using heteroleptic lanthanide initiators at 0˚C.

2. Experimental Procedure

2.1. Materials and Measurements

All air- or moisture-sensitive reactions were carried out under a dry nitrogen atmosphere, employing standard Schlenk line and glovebox techniques. Anhydrous solvents were purchased and used as received under nitrogen. α-MBL was purchased from Acros, stored under an inert atmosphere, and used as received. Deuterated solvents were purchased from Alfa Aesar and used as received. 3,5-di-tert-butyl-2-hydroxybenzaladehyde was purchased from Alfa Aesar while (R)-2-phenylglycinol was purchased from Acros Organic and used as

Scheme 1. Vinyl addition polymerization versus ROP of MBL.

received. (L)-Valinol[(S)-(+)-2-Amino-3-methyl-1-butanol] was purchased from TCI and used as received. All 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a JEOL-300 NMR spectrometer and referenced to CDCl3, C6D6 or C4D8O. Elemental analyses were performed by Midwest Microlab, Indianapolis, IN. Melting points were obtained on a Mel-Temp apparatus and are uncorrected. Optical rotations were recorded on a Rudolph Autopol III polarimeter with sodium D-line (589 nm) at room temperature. GC-MS analyses were performed on Bruker Scion 436-GC systems at 50˚C with electron impact ionization (70 eV). Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) analyses were performed using Malvern Malvern Viscotek GPCMax TDA 305 triple detection system (refractive index, right angle light scattering, and viscometer). Thermal analysis was done using TA Walters DMA Q800.

2.2. Synthesis of Ligands

2.2.1. (R)-(+)-2-Phenyl-2-Imino-1-Ethanol-2,4-Di-Tert-Butyl-Phenol (H2LI)

3,5-Di-tert-butyl-2-hydroxybenzaldehyde (4.00 g, 0.017 mol), and (R)-(+)-2-phenylglycinol (2.33 g, 0.017 mol) were dissolved in methanol (50 mL). The resulting solution was heated at reflux for 18 h and then cooled to room temperature. Solvent and water were removed using high vacuum Schlenk line to obtain yellow oil. The ligand was purified by column chromatography using hexane-ethyl acetate mixture (9:1) (5.56 g, 92.5 %). [α]D + 0.332 (c = 0.005, toluene). Elemental analysis: (Found: C 76.80, H 9.12, N3.16. C23H31NO2 requires C 78.15, H 8.84, N 3.96%). 1H NMR (300 MHz; CDCl3; 298 K) 1.36 (s, 9H, ArtBu), 1.49 (s, 9H, ArtBu), 3.96 (br, 2H, ArCH=NCH(Ph) OH), 4.50 (br, 1H, ArCH=NCH(Ph)CH2OH), 7.18 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.36 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.40 - 7.48 (br, 5H, ArH), 8.56 (s, 1H, ArCH=N), 9.81 (s, 1H, ROH), 11.62 (s, 1H, ArOH). GC-MS m/zcalcd for C23H31NO2: 353.51; found 353.5.

2.2.2. (S)-(+)-3-Methyl-2-Imino-1-Butanol-2,4-Di-Tert-Butyl-Phenol (H2LII)

3,5-Di-tert-butyl-2-hydroxybenzaldehyde (3.00 g, 0.013 mol), and L-valinol [(S)-(+)-2-Amino-3-methyl-1-butanol] (1.32 g, 0.013 mol) were dissolved in methanol (50 mL). The resulting solution was heated at reflux for 18 h and then cooled to room temperature. Solvent and water were removed using high vacuum Schlenk line to obtain yellow oil. Recrystallization from methanol at −10˚C (freezer) yielded yellow solid (4.025 g, 98.4%). Mp: 103.9˚C - 104.0˚C; [α]D + 0.006 (c = 0.005, toluene). Elemental analysis: (Found: C 75.32, H 10.16, N 4.58. C20H33NO2 requires C 75.19, H 10.41, N4.38 %). 1H NMR (300 MHz; CDCl3; 298 K) 0.95 (dd, 6H, J = 6.51 Hz, MeCHMe) 1.32 (s, 9H, ArtBu), 1.44 (s, 9H, ArtBu), 1.93 (m, 1H, J = 6.51 Hz, MeCHMe), 3.03 (br, 2H, ArCH=NCH(iPr)CH2OH), 3.80 (br, 1H, ArCH=NCH(iPr)CH2OH), 7.14 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.42 (s, 1H, ArH), 8.38 (s, 1H, ArCH=N), 9.87 (s, 1H, ROH), 11.65 (s, 1H, ArOH). 13C{H} NMR (75 MHz; CDCl3; 298 K) 18.9 (ArCMe3), 19.9 (ArCMe3), 29.5 (ArCMe3), 30.2 (MeCHMe), 31.6 (ArCMe3), 34.3 (MeCHMe), 35.1 (ArCH=NCH(iPr)CH2OH), 64.8 (ArC=NCH(iPr)CH2OH), 117.8, 126.3, 127.3, 136.8, 140.3, 158.2 (all ArC), 167.2 (ArCH=N NCH(iPr)CH2OH). GC-MS m/zcalcd for C20H33NO2: 319.49; found 319.4.

2.3. Synthesis of Lanthanide Complexes

2.3.1. [LIILaN{Si(CH3)3}2]THF(1)

A 50 mL Schlenk flask was obtained and dried in the oven. To a colorless THF solution (20 mL) of La[N(SiMe3)2]3 (0.25 g, 0.40 mmol) at −50˚C (acetone/dry ice mixture), a clear yellow toluene solution (10 mL) of ligand H2LII (0.128 g, 0.40 mmol) was added drop-wise under nitrogen using a Schlenkline. The resulting orange solution was stirred gently for 4 hours. Volatiles were removed in vacuo without heating to afford an orange-yellow solid that was dried under high vacuum to afford compound 1 (0.109 g, 44.80%); Mp: 184˚C; [α]D‒0.026 (c = 0.01, toluene). Elemental analysis: (Found: C 52.00, H 7.39, N3.74. C30H57N2O3Si2La (1) requires C 52.31, H 8.34, N 4.07 %). 1H NMR (300 MHz; C4D8O; 298 K) 0.2 ppm (br, 18H, -N[Si(CH3)3]2), 0.9ppm (d, 6H, -CH(CH3)2), 1.5ppm (s, 9H, −(CH3)3), 1.7 ppm (s, 9H, −(CH3)3), 2.0 ppm (m, 1H, NCH(iPr)CH2O), 3.2 ppm (m, 1H, NCH(iPr)CH2O), 3.7 ppm (m, 2H, NCH(iPr)CH2O), 7.3 ppm (s, 1H, ArH), 7.5 ppm (s, 1H, ArH), and 8.2 ppm (s, 1H, Ar-CH=N).

2.3.2. [LILaCl] (2)

A 100 mL Schlenk flask was obtained and dried in the oven. To a colorless THF solution (20 mL) of NaN(SiMe3)2 (0.77 g, 4.20 mmol) at room temperature, a clear yellow toluene solution (10 mL) of ligand H2LI (0.50 g, 1.40 mmol) was added drop-wise under nitrogen using a Schlenkline. The resulting orange-yellow solution was stirred gently for 4 hours. LaCl3 (0.34 g, 1.40 mmol) was added and the solution was refluxed overnight at 78˚C. White precipitate of NaCl was visible at bottom of flask. The supernatant clear greenish-yellow solution was decanted into another Schlenk flask. Volatiles were removed in vacuo to afford agreenish-yellow solid, which was further extracted with hexanes and dried under high vacuum to afford compound 2 (0.332 g, 42.86%); Mp: 170˚C; [α]D + 0.008 (c = 0.01, toluene). Elemental analysis: (Found: C 51.79, H 6.01, N2.21. C23H29NO2LaCl (2) requires C 52.53, H 5.56, N 2.66 %). 1H NMR (300 MHz; C4D8O; 298 K) 1.16 (br, 9H, ArtBu), 1.35 (br, 9H, ArtBu), 2.95 (br, 2H, ArCH=NCH(Ph)CH2O), 4.37 (br, 1H, ArCH=NCH(Ph)), 6.85 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.32 - 7.38 (br, 5H, ArH), 7.84 (br, 1H, ArH), 8.58 (s, 1H, ArCH=N).

2.3.3. [LIILaCl] (3)

A 100 mL Schlenk flask was obtained and dried in the oven. To a colorless THF solution (20 mL) of NaN(SiMe3)2 (0.88 g, 4.80 mmol) at room temperature, a clear yellow toluene solution (10 mL) of ligand H2LII (0.5 g, 1.6 mmol) was added drop-wise under nitrogen using a Schlenk line. The resulting orange-yellow solution was stirred gently for 4 hours. LaCl3 (0.39 g, 1.6 mmol) was added and the solution was refluxed overnight at 78˚C. White precipitate of NaCl was visible at bottom of flask. The supernatant clear greenish-yellow solution was decanted into another Schlenk flask. Volatiles were removed in vacuo to afford a greenish-yellow solid, which was further extracted with hexanes and dried under high vacuum to afford compound 3 (0.324 g, 41.25%); Mp: 180˚C; [α]D + 0.003 (c = 0.01, toluene). Elemental analysis: (Found: C 49.39, H 7.06, N 2.81. C20H31NO2LaCl (3) requires C 48.84, H 6.35, N 2.85 %). 1H NMR (300 MHz; C4D8O; 298 K)\1.0 ppm (br, 6H, −CH(CH3)2), 1.2 ppm (s, 9H, −(CH3)3), 1.4 ppm (s, 9H, −(CH3)3), 2.3 ppm (br, 1H, NCH(iPr)CH2O), 2.9 ppm (br, 1H, NCH(iPr)CH2O), 3.4 ppm (m, 2H, NCH(iPr)CH2O), 7.2 ppm (s, 1H, ArH), 7.3 ppm (s, 1H, ArH), and 8.4 ppm (s, 1H, Ar-CH=N).

1) General polymerization procedure

All materials were prepared in a glovebox and all reactions (air- and moisture- sensitive) were carried out in flamed Schlenk-type glassware on a Schlenk line. The monomer/initiator ratio employed was 500:1. In a 25 ml flame dried Schlenk flasks, 1.0 g of the monomer (α-methylene-γ-butyrolactone) was added to the calculated ratio of the catalyst along with 8.0 ml of DMSO. The polymerization reaction was maintained at 0˚C using acetone and ice. After the desired reaction time, the reaction was quenched with 2.0 ml of 5% acidified methanol (HCl/MeOH) and the solid was allowed to precipitate in the freezer (−15˚C) overnight. The white polymer product was filtered, dried and characterized by 1HNMR spectroscopy (d6-DMSO), Gel Permeation Chromatography(DMSO) to obtain polymer microstructure, and molecular weights (Mn and Mw), respectively. Thermal analyses of polymer were done using DMA Q800 to obtain Tg.

2) Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) data procedure

GPC analyses were performed on a Malvern ViscotekGPCMax TDA 305 triple detection system (RI, RALS, and viscometer) using a two mixed bed D6000M columns. Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) was used as the dissolution solvent and mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.75 mL∙min−1. The temperature of the detectors and columns were set at 50˚C. The calibration method used was triple detection. Samples were dissolved at concentration between 1 - 5 mg/mL and dissolved overnight. Allowing for dissolution overnight, the samples were not fully in solution, so heat at 50˚C for 1 hour was applied and the samples were allowed to cool. Samples were filtered through a 0.2 um Nylon syringe filter prior to analysis.

3) Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer (DMA) data procedure

Melting temperature, Tm, of polymer samples was done using melting point apparatus while glass transition temperature was obtained using TA Walters Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer, DMA Q800. Tg was obtained as Tan Delta value from DMA Q800 Multi-Frequency-Strain Mode using a powder clamp Temperature Ramp method mounted onto a dual cantilever at 3.00˚C /min from 25˚C to 150˚C and 20.00 µm Amplitude.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis of Ancillary Ligands

This project discusses the synthesis of cross-linked biodegradable polyesters using new heteroleptic lanthanide catalytic system with three main components LLaX: where L is a chiral dianionic multidentate ancillary ligand, H2LI and H2LII (see Figure 1), La is a highly electropositive trivalent lanthanum metal and X is an initiator (trimethylsilylamide, chloride) that initiates ring-opening of cyclic ester monomer. In order to initiate ROP, the initiating group, X, must be a good nucleophile and monodentate with labile coordination to lanthanide. The ancillary ligand, L, is to stabilize the metal catalyst during ROP as it remains bound to the lanthanide metal during coordination-insertion mechanism for ROP of lactones.

Newly synthesized ligands H2LI and H2LII (Figure 1) will be employed as L component in the catalytic system LLaX [41] [49] [50] [51] [52] [53] . Deprotonation of phenolic hydrogens in H2LI and H2LII will afford dianionic multidentate ancillary ligands with different steric and electronic demands. The ligands were synthesized via Mannich condensation reactions using 3,5-Di-tert-butyl-2-hydroxybenzaldehyde and chiral auxillary, (R)-(+)-2-phenylglycinol (H2LI) and [(S)-(+)-2-Amino-3-methyl-1-butanol (H2LII) (Scheme 2). The synthesized ligands were characterized by NMR, and elemental analysis.

3.2. Synthesis of Lanthanide Complexes

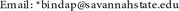

Attachment of ligands H2LI and H2LII to homoleptic lanthanum amide offers new heteroleptic metal complexes for metal catalyzed ring-opening polymerization of MBL. A diverse array of synthetic strategies for the different catalyst precursors is proposed from ligand exchange reactions (see Scheme 3) to salt elimination metathesis (see Scheme 4). The synthesis of catalysts via acid-base ligand exchange reaction (Scheme 3) offers a superior, cleaner approach over

Figure 1. New [ONO] ancillary phenolate ligands and intended heteroleptic Lanthanide Catalyst System showing catalytic pocket around metal coordination site.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of ligand H2LII via condensation reaction.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of compound 1via ligand exchange reactions.

Scheme 4. Synthesis of LLaCl catalyst via salt metathesis reactions.

salt metathesis reactions (Scheme 4) since the by-products from acid-base reactions can be readily removed, making it easier to obtain analytically pure compounds.

New lanthanum compound 1 was synthesized using homoleptic La{N(SiMe3)2}3 and ligand H2LII in toluene and THF to afford [LIILaN{Si(CH3)3}2] THF 1 (Scheme 3). The synthesized heteroleptic lanthanum compound was fully characterized by NMR spectroscopy, elemental analysis and melting point (see experimental). Meanwhile, compounds 2 and 3 were isolated via salt metathesis reaction using one equivalent of ligands H2LI,II, three equivalent of NaN{Si(CH3)3}2, and one equivalent of LaCl3 in refluxing THF for 18 h (Scheme 4). The goal was to synthesize the amido compounds but heterolepticlanthanide chloride was isolated presumably as slight amount of water from the 99% dry THF solvent must have reacted with some of the sodium amide. 1H NMR spectroscopy of compound 1 in d8-THF(C4D8O) revealed one LII molecule and asilylamide ligand (Figure 2) while NMR spectroscopy of 2 and 3 in d8-THF(C4D8O) also confirmed their formulation. This was supported by elemental analysis results and chloride test. Compound 1 gave a negative chloride test while 2 and 3 gave white precipitate with AgNO3 indicative of the presence of chloride. It was very difficult to isolate good single crystals for X-ray determination.

3.3. Ring-Opening Homopolymerization of MBL Using New Lanthanide Complexes

Unsaturated aliphatic polyesters, which can be synthesized from ROP of naturally available α-methylene-γ-butyrolactone (MBL), are of scientific and

Figure 2. 1HNMR of LII La(NSiMe3)2THF (1) in d8-THF.

technological interest for producing tailor-made functionalized biodegradable shape memory materials. The unfavorable thermodynamics involved in the ROP of MBL results in too small negative change of enthalpy (ΔH) to offset a large negative entropy change (ΔS). As a result, MBL prefers vinyl addition polymerization to ROP.

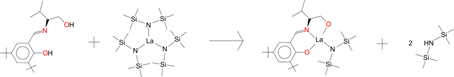

Hong and Chen recently reported the first Ring-Opening Copolymerization (R˚C) of MBL with ε-caprolactone (ε-CL) catalyzed by homoleptic lanthanide tris(bistrimethylsilyl)amide Ln[N(SiMe3)2]3, that produced exclusively an unsaturated copolyester PMBL-co-PCL (Scheme 5) [42] . Despite the non-homo- polymerizability of unsaturated gamma lactones toward ring-opening polymerization due to the relative low ring-strain energy (high thermodynamic stability) of its five-membered ring, copolymerization with ε-CL using lanthanide coordination catalytic system, coupled with appropriate reaction conditions (relatively nonpolar solvent and low temperature at 0˚C to-20˚C) was an effective way of shutting down the vinyl-addition pathway via conjugate addition across the ex Cyclic C=C double bond (ring retention). After carrying out extensive investigations, Hong and Chen also reported that non polar solvents such as toluene was able to suppress the competing vinyl-addition polymerization while copolymerization with a high strain lactone and low reaction temperature favored ROP of the five-membered unsaturated lactones [42] . Using similar reaction conditions with newheteroleptic lanthanide complexes LLaX using the ligands H2LI and H2LII, ring-opening polymerization of MBL was achieved. Homoleptic LnX3 such as Ln[N(SiMe3)2]3 has shown to catalyze ROP very rapidly without any polymerization control due to lack of a stabilizing ancillary ligand such as H2LI and H2LII, and as a result form competing vinyl-addition polymerization and ROP (Scheme 1) where copolyester PMBL-co-PCL recorded high molecular weight distribution with polydispersity up to 2.77 [42] . The high Lewis acidity and coordination number of the lanthanides (desirable for monomer coordination and activation) and the high nucleophilicity of amides and alkoxides (desirable

Scheme 5. Ring Opening Copolymerization (ROC) of MBL and ε-CL to form PMBL-co-PCL.

for chain initiation) is illustrated in the mechanism presented in Scheme 6.

Compounds 1, 2, and 3 were treated with MBL and the results are summarised in Table 1 below. All polymerization reactions were performed in DMSO at 0˚C. Entry 1 is the control reaction which shows no polymerization, even after 24 h. Furthermore, there was no polymer formation with compound 1 after 1 hour which is probably due to slow initiation process as a result of bulky amidegroup and non-polymerizability of MBL (Table 1, entry 2). However, compound 2 and 3 gave significant polymer formation after 1 hour (Table 1, entries 3 - 4). All polymerization reactions were quenched with acidified methanol. Due to high solubility of this polymer in DMSO, the reaction flask was kept in freezer overnight to allow precipitation of the white PMBL product. This reactivity suggests that the chloride is better at initiating ROP of MBL than the bulky amide. 1H NMR analysis of the polymer obtained showed that the methylene protons of exocyclic C=C bond at 5.7 ppm and 6.0 ppm were significantly absent indicative of vinyl addition reactions to form branched polymer (see Figure 3).

GPC analysis of the polymer obtained supports highly branched polyester with a very high molecular weight, about 25 times larger compared to the expected linear unsaturated polyester. The hydrodynamic volume was also very large. Because these compounds were so large compared to expected linear polymers and to ensure reproducibility in analysis since these polymers are novel, a comparison of the samples was repeated with a 73 kDa Dextran polymer standard at different concentrations and the following chromatograms were obtained showing similar molecular weight as previously analyzed (see Figure 4). All these samples displayed a much larger hydrodynamic size than the 73 kDa Dextran standard. Sample #2 (Table 1, entry 4) showed higher molecular weight of 754 kDa while sample #1 gave 577 kDa (Table 1, entry 3). Both polymeric samples gave a narrow polydispersity of 1.3. The GPC was analyzed using Malvern Viscotek GPCMax triple detector system (refractive index, light scattering and viscometer) which has been proven to successfully determine the absolute molecular weight of polymeric materials. The only explanation to the large molecular weight is the production of highly branched polymer through vinyl addition of the C=C double bonds bringing many linear PMBL polymers into one unit. This is supported by 1HNMR spectra of the polymers, which showed a significant reduction and in some cases disappearance of the exocyclic CH=CH double bond proton signals. This also explains the difficulty in solubility of these branched polymers. Due to its higher molecular weight, sample #2 gave higher

(a)

(a)

(b)

(b)

(c)

(c)

Scheme 6. Proposed Mechanism for ROP of MBL.

Figure 3. 1H NMR of PMBL (Table 1, entry 3) in d6-DMSO.

Figure 4. GPC Data of newly synthesized branched PMBL.

Figure 5. DMA Data of newly synthesized branched PMBL showing Tg values for entries 3.

Figure 6. DMA Data of newly synthesized branched PMBL showing Tg values for entries 4.

melting and glass transition temperatures than sample #1 (Figure 5 and Figure 6). The Tg for sample #1 was 87.61˚C while that for sample #2 was 123.38˚C.

4. Conclusion

New heteroleptic lanthanide complexes supported by newly synthesized tridentate dianionic [ONO] aminophenolate ligands were characterized by NMR and

Table 1. Polymerization of MBL using La complexes at 0˚C.

a: Monomer to initiator ratio. b: Mw and Mw/Mn (PDI) of polymer determined by GPC; PDI = polydispersity index.

elemental analysis. We also report for the first time, the ring-opening homopolymerization of α-methylene-γ-butyrolactone into highly branched polyester using lanthanide initiators at 0˚C. GPC analysis of the newly synthesized branched polymer gave large molecular weight above 500,000 g/mol and a narrow polydispersity of 1.3. The glass-transition temperatures of the polymer samples were recorded at 87.61˚C and 123.38˚C using a Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer, DMA Q800. The newly synthesized polyester is suitable candidates for medical implantation devices and shape memory materials.

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work fully supported by the U.S. Army Research Laboratory (ARL) and the U.S. Army Research Office (ARO) under contract/grant award number 67208-CH-REP. The authors are also grateful for GPC and DMA instrumentation grant from ARL and ARO under contract/grant number P68862-CH-REP for supporting this project through polymer characterization.

Cite this paper

Binda, P., Barnes, Z., Guthrie, D. and Ford, R. (2017) Highly Branched Poly(α-Methylene-γ-Butyrolactone) from Ring-Opening Homopolymerization. Open Journal of Polymer Chemistry, 7, 76-91. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojpchem.2017.74006

References

- 1. Joseph, J.G. (2006) Polymers for Tissue Engineering, Medical Devices, and Regenerative Medicine. Concise General Review of Recent Studies. Polymers for Advanced Technologies, 17, 395-418.

https://doi.org/10.1002/pat.729 - 2. Isogai, N., Asamura, S., Hagishi, T., Ikada, Y., Morita, S., Hillyer, J. and Landis, W.J. (2004) Tissue Engineering of an Auricular Cartilage Model Utilizing Cultured Chondrocyte-Poly(L-Lactide-ε-Caprolactone) Scaffolds. Tissue Engineering, 10, 673-687.

https://doi.org/10.1089/1076327041348527 - 3. Jacoby, M. (2001) Applying Engineering, Materials, and Chemistry Principles, Researchers Produce Safe, Smart, and Effective Implantable Devices. Chemical & Engineering News, 79, 30.

https://doi.org/10.1021/cen-v079n006.p030 - 4. Panyam, J. and Labhasetwar, V. (2003) Biodegradable Nanoparticles for Drug and Gene Delivery to Cells and Tissue. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 55, 329-347.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-409X(02)00228-4 - 5. Mu, L. and Feng, S. (2003) A Novel Controlled Release Formulation for the Anticancer Drug Paclitaxel (Taxol®): PLGA Nanoparticles Containing Vitamin E TPGS. Journal of Controlled Release, 86, 33-48.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-3659(02)00320-6 - 6. Waris, E., Ninkovic, M., Harpf, C., Ninkovic, M. and Ashammakhi, N. (2004) Self-Reinforced Bioabsorbableminiplates for Skeletal Fixation in Complex Hand Injury: Three Case Reports. Journal of Hand Surgery, 29A, 452-457.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2004.01.013 - 7. Caldorera-Moore, M., Nicholas, A. and Peppas, N.A. (2009) Micro- and Nanotechnologies for Intelligent and Responsive Biomaterial-Based Medical Systems. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 16, 1391-1401.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2009.09.002 - 8. Slager, J. and Domb, A.J. (2003) Biopolymer Stereocomplexes. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 55, 549-583.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-409X(03)00042-5 - 9. Gollwitzer, H., Ibrahim, K., Meyer, H., Mittelmeier, W., Busch, R. and Stemberger, A. (2003) Antibacterial Poly(d,l-Lactic Acid) Coating of Medical Implants Using a Biodegradable Drug Delivery Technology. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 51, 585-591.

https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkg105 - 10. Lendlein, A. and Langer, R. (2002) Biodegradable, Elastic Shape-Memory Polymers for Potential Biomedical Applications. Science, 296, 1673-1676.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1066102 - 11. Jikei, M., Takeyama, Y., Yamadoi, Y., Shinbo, N., Matsumoto, K., Motokawa, M., Ishibashi, K. and Yamamoto, F. (2015) Synthesis and Properties of Poly(L-lactide)-Poly(ε-caprolactone) multibl Ck Copolymers by the Self-Polyc Ondensation of Dibl Ckmacromonomers. Polymer Journal, 47, 657-665.

https://doi.org/10.1038/pj.2015.49 - 12. Haba, O. and Itabashi, H. (2014) Ring-Opening Polymerization of a Five-Membered Lactone Trans-Fused to a Cyclohexane Ring. Polymer Journal, 46, 89-93.

https://doi.org/10.1038/pj.2013.70 - 13. Wu, X.-Y., Ren, Z.-G. and Lang, J.-P. (2014) Ni(II) Tetraphosphine Complexes as Catalysts/Initiators in the Ring Opening Polymerization of ε-Caprolactone. Dalton Transactions, 43, 1716-1723.

https://doi.org/10.1039/C3DT52412D - 14. Stanlake, L.J.E., Beard, J.D. and Schafer, L.L. (2008) Rare-Earth Amidate Complexes. Easily Accessed Initiators for ε-Caprolactone Ring-Opening Polymerization. Inorganic Chemistry, 47, 8062-8068.

https://doi.org/10.1021/ic8010635 - 15. Celiz, A.D. and Scherman, O.A. (2008) Controlled Ring-Opening Polymerization Initiated via Self-Complementary Hydrogen-Bonding Units. Macromolecules, 41, 4115-4119.

https://doi.org/10.1021/ma702699t - 16. Rajashekhar, B., Roymuhury, S.K., Chakraborty, D. and Ramkumar, V. (2015) Group 4 Metal Complexes of Trost’s Semi-Crown Ligand: Synthesis, Structural Characterization and Studies on the Ring-Opening Polymerization of Lactides and ε-Caprolactone. Dalton Transactions, 44, 16280-16293.

https://doi.org/10.1039/C5DT02267C - 17. Delbridge, E.E., Dugah, D.T., Nelson, C.R., Skelton, B.W. and White, A.H. (2007) Synthesis, Structure and Oxidation of New Ytterbium(II) bis(phenolate) Compounds and Their Catalytic Activity towards ε-Caprolactone. Journal of the Chemical Society, Dalton Transactions, 143-153.

https://doi.org/10.1039/B613409B - 18. Binda, P.I. and Delbridge, E.E. (2007) Synthesis and Characterisation of Lanthanide Phenolate Compounds and Their Catalytic Activity towards Ring-Opening Polymerisation of Cyclic Esters. Journal of the Chemical Society, Dalton Transactions, 4685-4692.

https://doi.org/10.1039/b710070a - 19. Binda, P.I., Delbridge, E.E., Abrahamson, H.B. and Skelton, B.W. (2009) Coordination of Substitutionally Inert Phenolate Ligands to Lanthanide(II) and (III) Compounds—Catalysts for Ring-Opening Polymerization of Cyclic Esters. Journal of the Chemical Society, Dalton Transactions, 2777-2787.

https://doi.org/10.1039/b821770j - 20. Zats, G.M., Arora, H., Lavi, R., Yufit, D. and Benisvy, L. (2011) Phenolate and Phenoxyl Radical Complexes of Cu(II) and Co(III), Bearing a New Redox Active N,O-Phenol-Pyrazole Ligand. Dalton Transactions, 40, 10889-10896.

https://doi.org/10.1039/c1dt10615e - 21. Li, W., Xue, M., Tu, J., Zhang, Y. and Shen, Q. (2012) Syntheses and Structures of Lanthanide Borohydrides Supported by a Bridged bis(amidinate) Ligand and Their High Activity for Controlled Polymerization of ε-Caprolactone, L-Lactide and rac-Lactide. Dalton Transactions, 41, 7258-7265.

https://doi.org/10.1039/c2dt30096f - 22. Darensburg, D.J. and Karroonnirun, O. (2010) Ring-Opening Polymerization of Lactides Catalyzed by Natural Amino-Acid Based Zinc Catalysts. Inorganic Chemistry, 49, 2360-2371.

https://doi.org/10.1021/ic902271x - 23. Wheaton, C.A., Hayes, P.G. and Ireland, B.J. (2009) Complexes of Mg, Ca and Zn as Homogeneous Catalysts for Lactide Polymerization. Dalton Transactions, 4832-4846.

https://doi.org/10.1039/b819107g - 24. Wang, L. and Ma, H. (2010) Zinc Complexes Supported by Multidentateaminophenolate Ligands: Synthesis, Structure and Catalysis in Ring-Opening Polymerization of rac-Lactide. Dalton Transactions, 39, 7897-7910.

https://doi.org/10.1039/c0dt00250j - 25. Song, S., Zhang, X., Ma, H. and Yang, Y. (2012) Zinc Complexes Supported by Claw-Type Aminophenolate Ligands: Synthesis, Characterization and Catalysis in the Ring-Opening Polymerization of rac-Lactide. Dalton Transactions, 41, 3266-3277.

https://doi.org/10.1039/c2dt11767c - 26. Drouin, F., Oguadinma, P.O., Whitehorne, T.J.J., Prud’homme, R.E. and Schaper, F. (2010) Lactide Polymerization with Chiral β-Diketiminate Zinc Complexes. Organometallics, 29, 2139-2147.

https://doi.org/10.1021/om100154w - 27. Labourdette, G., Lee, D.J., Patrick, B.O., Ezhova, M.B. and Mehrkhodavandi, P. (2009) Unusually Stable Chiral Ethyl Zinc Complexes: Reactivity and Polymerization of Lactide. Organometallics, 28, 1309-1319.

https://doi.org/10.1021/om800818v - 28. Börner, J., Vieira, I.S., Pawlis, A., Döring, A., Kuckling, D. and Pawlis, S.H. (2011) Mechanism of the Living Lactide Polymerization Mediated by Robust Zinc Guanidine Complexes. Chemistry: A European Journal, 17, 4507-4512.

https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201002690 - 29. Garcés, A., Sánchez-Barba, L.F., Alonso-Moreno, C., Fajardo, M., Fernández-Baeza, J., Otero, A., Lara-Sánchez, A., López-Solera, I. and Rodriguez, A.M. (2010) Hybrid Scorpionate/Cyclopentadienyl Magnesium and Zinc Complexes: Synthesis, Coordination Chemistry, and Ring-Opening Polymerization Studies on Cyclic Esters. Inorganic Chemistry, 49, 2859-2871.

https://doi.org/10.1021/ic902399r - 30. Gao, B., Duan, R., Pang, X., Li, X., Qu, Z., Shao, H., Wang, X. and Chen, X. (2013) Zinc Complexes Containing Asymmetrical N,N,O-Tridentate Ligands and Their Application in Lactide Polymerization. Dalton Transactions, 42, 16334-16342.

https://doi.org/10.1039/c3dt52016a - 31. Tschan, M.J.-T., Guo, J., Raman, S.K., Brulé, E., Roisnel, T., Marie-Noelle Rager, M.N., Legay, R., Durieux, G., Rigaud, B. and Thomas, C.M. (2014) Zinc and Cobalt Complexes Based on Tripodal Ligands: Synthesis, Structure and Reactivity toward Lactide. Dalton Transactions, 43, 4550-4564.

https://doi.org/10.1039/c3dt52629a - 32. Hens, A., Mondal, P. and Rajak, K.K. (2013) Synthesis, Structure and Spectral Properties of O,N,N Coordinating Ligands and Their Neutral Zn(II) Complexes: A Combined Experimental and Theoretical Study. Dalton Transactions, 43, 14905-14915.

https://doi.org/10.1039/c3dt51571k - 33. Ikpo, N., Saunders, L.N., Walsh, J.L., Smith, J.M.B., Dawe, L.N. and Kerton, F.M. (2011) Zinc Complexes of Piperazinyl-Derived Aminephenolate Ligands: Synthesis, Characterization and Ring-Opening Polymerization Activity. European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry, 5347-5359.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ejic.201100703 - 34. Mou, Z., Liu, B., Wang, M., Xie, H., Li, P., Li, L., Li, S. and Cui, D. (2014) Isoselective Ring-Opening Polymerization of rac-Lactide Initiated by Achiral Heteroscorpionatezwitterionic Zinc Complexes. Chemical Communications, 50, 11411-11414.

https://doi.org/10.1039/C4CC05033A - 35. Wang, H. and Ma, H. (2013) Highlydiastereoselective Synthesis of Chiral Aminophenolate Zinc Complexes and Isoselective Polymerization of rac-Lactide. Chemical Communications, 49, 8686-8688.

https://doi.org/10.1039/c3cc44980g - 36. Takenouchi, S., Takasu, A., Inai, Y. and Hirabayashi, T. (2002) Effects of Geometrical Difference of Unsaturated Aliphatic Polyesters on Their Biodegradability II. Isomerization of Poly(maleic anhydride-co-propylene oxide) in the Presence of Morpholine. Polymer Journal, 34, 36-42.

https://doi.org/10.1295/polymj.34.36 - 37. Doulabi, A.S.H., Mirzadeh, H., Imani, M., Sharifi, S., Atai, M. and Mehdipour-Atai, S. (2008) Synthesis and Preparation of Biodegradable and Visible Light Crosslinkable Unsaturated Fumarate-Based Networks for Biomedical Applications. Polymers for Advanced Technologies, 19, 1199-1208.

https://doi.org/10.1002/pat.1112 - 38. Zhou, J., Schmidt, A.M. and Ritter, H. (2010) Bicomponent Transparent Polyester Networks with Shape Memory Effect. Macromolecules, 43, 939-942.

https://doi.org/10.1021/ma901402a - 39. Murray, A.W. and Reid, R.G. (1985) Convenient Synthesis of α-Epoxylactones (4-Oxo-1,5-dioxaspiro[2.4]heptanes and -[2.5]octanes). Synthesis, 1985, 35-38.

https://doi.org/10.1055/s-1985-31096 - 40. Jenkins, S.M., Wadsworth, H.J., Bromidge, S., Orlek, B.S., Wyman, P.A., Riley, G.J. and Hawkins, J. (1992) Substituent Variation in Azabicyclic Triazole- and Tetrazole-Based Muscarinic Receptor Ligands. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 35, 2392-2406.

https://doi.org/10.1021/jm00091a007 - 41. Grieco, P.A. (1975) Methods for the Synthesis of α-Methylene Lactones. Synthesis, 1975, 67-82.

https://doi.org/10.1055/s-1975-23668 - 42. Hong, M. and Chen, Y.-X. (2014) Coordination Ring-Opening Copolymerization of Naturally Renewable α-Methylene-γ-Butyrolactone into Unsaturated Polyesters. Macromolecules, 47, 3614-3624.

https://doi.org/10.1021/ma5007717 - 43. Mosnek, J. and Matyjaszewski, K. (2008) Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization of Tulipalin A: A Naturally Renewable Monomer. Macromolecules, 41, 5509-5511.

https://doi.org/10.1021/ma8010813 - 44. Kitson, R.R.A., Millemaggi, A. and Taylor, R.J.K. (2009) The Renaissance of α-Methylene-γ-butyrolactones: New Synthetic Approaches. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 48, 9426-9451.

https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.200903108 - 45. Williams, C.K. and Hillmyer, M.A. (2008) Polymers from Renewable Resources: A Perspective for a Special Issue of Polymer Reviews. Polymer Reviews, 48, 1-10.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15583720701834133 - 46. Sinnwell, S. and Ritter, H. (2006) Ring-Opening Homo- and Copolymerization of α-Methylene-ε-Caprolactone. Macromolecules, 39, 2804-2807.

https://doi.org/10.1021/ma0527146 - 47. Hoffman, H.M.R. and Rabe, J. (1985) Synthesis and Biological Activity of α-Methylene-γ-butyrolactones. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 24, 94-110.

https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.198500941 - 48. AllcCk, H.R., Lampe, F.W. and Mark, J.E. (2003) Contemporary Polymer Chemistry. 3rd Edition, Pearson.

- 49. Odian, G. (1991) Principles of Polymerization. 3rd Edition, Wiley-Interscience.

- 50. Sawada, H. (1976) Thermodynamics of Polymerization. Marcel-Dekker.

- 51. Houk, K.H., Jabbari, A., Hall, H.K. and Aleman, C. (2008) Why δ-Valerolactone Polymerizes and γ-Butyrolactone Does Not. The Journal of Organic Chemistry, 73, 2974-2978.

https://doi.org/10.1021/jo702567v - 52. Hong, M. and Chen, Y.-X. (2016) Completely Recyclable Biopolymers with Linear and Cyclic Topologies via Ring-Opening Polymerization of γ-Butyrolactone. Nature Chemistry, 8, 42-49.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nchem.2391 - 53. Hong, M. and Chen, Y.-X. (2016) Towards Truly Sustainable Polymers: Metal-Free Recyclable Polyester from Bio-Renewable Non-Strained Gamma-Butyrolactone. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 55, 4188-4193.

https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201601092