Open Journal of Social Sciences

Vol.04 No.08(2016), Article ID:69687,7 pages

10.4236/jss.2016.48002

Tourism Information Value and Its Hierarchical Structure

Zhaoming Deng

Department of Finance and Economics, Graduate School of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Beijing, China

Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 18 July 2016; accepted 9 August 2016; published 12 August 2016

ABSTRACT

In an era of information explosion, to make good use of tourism information has become an urgent issue. This paper studies the composition of the tourism information value and the degree of its importance based on the tourists’ perception. Through factor analysis, five factors were identified from tourism information value: hedonic value, risk-avoidance value, utilitarian value, social value and self-actualization value. According to different degree of importance evaluation, the tourism information value was divided into three hierarchical levels, namely, the core value of information, the basic information value and the relationship information value, while tourists considered the risk-avoidance value as the most important one. In practical terms, the findings of this study can be useful to marketers in creating promotional campaigns, providing them with a better understanding of what information appeals to their markets.

Keywords:

Tourism Information, Value, Hierarchical Structure, Perception

1. Introduction

The delivering of information is a crucial part in travel activities, as well as a key stage in the marketing and service of tourism destination [1] . In such an era of information explosion, especially with the tourism market competition increasingly intensified, consumers often feel confused when facing enormous information. Therefore, it is how to make good use of tourism information to campaign service marketing that has become an urgent issue for the marketers [2] . Information service is a two-way concept, since the competition of tourism market is so fierce today, it becomes particularly important that we could make the potential tourists receive our information and accept it. Based on the Perception-Attitude-Behavior Theory, the customers’ value towards the information has a direct influence on their attitude to goods or service and further affects their purchasing behavior [3] . Thus, it can be seen that the information value plays an important role in the customer’s travel decision-making process, and it is essential for promotion to provide the customers with appropriate information that caters to their needs. This empirical research focuses on the tourism information value and its dimensions, in the hope of offering practical suggestions for tourism marketers.

2. Literature Review

There are numerous studies on tourism information based on tourists’ perception, some of which involve the information value. According to Cees (2000), tourists fulfill their needs for value by information searching, and simultaneously, their perception value for goods or service which emerges during the process of consumption significantly affect their choice preference for products [4] . The information can be more easily accepted and increase the chances of purchasing (Diehl & Zauberman, 2005) [5] . Vogt and Fesenmaier (1998) suggested that once the tourists approve the value of information they have searched, they will further search for more related information to elaborate their travel decision [6] .

Values are fundamentally embedded in individuals’ needs and wants (Rokeach, 1973) [7] . As a result, tourists’ perception of information value is closely associated with tourism demand. Based on questionnaire survey of the “self-help” visitors’ demands for related information about Beijing city, Wen (2007) discussed demands for the information from six aspects: food, accommodation, transport, touring, shopping, and entertainment [8] . The information mentioned in this research suffices functional value demands, maximizing positive rewards and minimizing negative outcomes. However, considering the nature of tourism, which involves sightseeing, rest and other leisure activities, information about tourist products may not just be functional or practical. In other words, with regard to tourism information value, we can acquire a larger concept and fruitful academic achievements (Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982) [9] .

The ultimate goal of information searching via external sources is to seek tangible benefits, such as more monetary worth of utilities, better itinerary and appropriate advice for risk-avoidance, etc. This kind of pursuit for actual benefits reveals the functional value of tourism information (Van, 1986) [10] . Meanwhile, the information search behavior may bring a sort of joy of experience. In other words, information can provide an experiential benefit, evoking emotional responses such as aesthetics feelings or enjoyment during an information search at the sight of information on a resort, e.g. fine pictures, exotic culture and novel activities (Hirschman & Holbrook, 1982) [11] . In addition, tourism information can provide the tourists with topics of conversation to chat with their friends and relatives, making them feel respected and proud of themselves and fulfilling their needs for self-actualization (Dimanche & Samdahl, 1994) [12] . These, which have nothing to do with utility but still have an important impact on the travel decision-making process, can be named experiential values. To sum up, there could be different approaches to differentiating information dimensions (Mi-Hea Cho, 2008) [13] .

3. Methodology

3.1. Questionnaire Design

Based on a literature review, we designed measurement scales for tourism information value. The pre-trip information search effort scale was developed according to Guo’s (2008) research [14] . The list of measurement items of tourism information value was derived from both literature review [11] - [13] and interviews. The 27 items were then submitted to a panel of experts comprised of 25 tourism majored teachers and graduate students (see Table 1). The panel judged the applicability of the measurement items to the study. The list was then recompiled based on the expert panel’s suggestions and according to which, a draft of the questionnaire was then designed. In the final version, 25 items for tourism information value left.

The questionnaire used in the survey consisted of four sections: the first section focused on the respondents’ demographic background, with items relating to gender, age, family monthly income, education level. The sec- ond section was designed to gather the information of travel-related behaviors. The third section was a scale designed to test the pre-trip information search effort. There were four questions in this section using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “1” (never search) to “5” (search actively). The final section included a tourism information value scale. The table consisted of 25 items, following the statement “Please try to recall the travel related information you have searched for when planning your trip in the last year, and how important do you think the value of the following information is to you?” Individuals ranked the importance of the information on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “1” (not at all important) to “5” (very important).

Table 1. Items for tourism information value.

3.2. Data Collection

From Oct. 1 to Oct. 10, 2015, the survey was conducted at famous tourist attractions such as the Shichahai Lake Park, the Summer Palace in Beijing City, the capital of PRC, in a self-administered way. The questionnaires were distributed by experienced tourism majored students. These students were well-trained to do this job and were given clear instructions including the purpose of the study and the investigation procedures. A total number of 1200 questionnaires were distributed and 1006 usable responses were obtained. To ensure a scientific research, questionnaires were rejected when they fulfilled the following two conditions:

a) No trip was made in the past year;

b) Did not search for information positively.

After further selection, the final number of the samples reduced to 562.

3.3. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS 20.0 Statistical packages. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with a varimax rotation was performed on the data collected to determine the dimensions of the scales. To ensure that each attribute loaded only on one factor, the items which had factor loadings lower than 0.4 or cross-loaded on more than one factor were eliminated. The internal reliability of each factor was then measured by using Cronbach’s alpha. A low alpha coefficient suggests that an item has a low contribution to the measurement of the construct of interest. Thus, factors with lower than 0.7 Cronbach’s Alpha were considered for elimination.

4. Result

4.1. Sample Profile

The profile of respondents is shown in Table 2. More than half of the respondents were female (55.3%), 20 - 29

Table 2. Sample profile.

a. The overall percentage may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

years of age (52.3%), and well educated. Most respondents had graduated from college or completed graduate work (54.4%), and most had an average monthly income of more than RMB 2000 (93.9%).

4.2. Tourism Information Value

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was carried out to derive the underlying dimensions of tourism information value. This research adopted a principal component extraction method with varimax rotation and a minimum eigenvalue of one rule to determine the number of factors extracted. Items with factor loadings lower than 0.4 on more than one factor were dropped as a principle. A five-factor solution, with 15 indicators being retained, accounted for approximately 64.754% of the total variance. Factor loadings of the indicators ranged from 0.525 to 0.817, above the suggested threshold value of 0.5. The Cronbach’s alpha for the five factors varied from 0.722 to 0.869, well above the generally agreed upon lower limit of 0.7. The five factors were labeled as hedonic value, risk-avoidance value, self-actualization value, utilitarian value, and social value. Results are reported in Table 3.

Table 3. Common factors of tourism information value

a. The overall percentage may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

4.3. Hierarchical Structure

After identifying the common factors for tourism information value, we continue to study its hierarchical structure among these factors based on the tourist’s perceptions. In the questionnaire, every respondent give their opinion of the tourism information value by choosing “1” (not at all important) to “5” (very important), which means that the number “3” indicates a medium importance. We selected all the “3”, “4” and “5” options and the importance of five constructs and indicators was evaluated by the cumulative percentage of these three choices. The result is shown in Table 4.

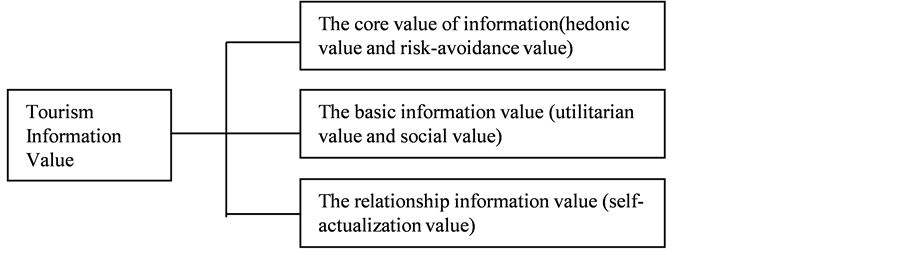

The result suggests that there exist differences of the importance between factors. According to the difference levels, five constructs were classified into three levels. The first level of factors, whose cumulative percentage is above 80%, is named “the core value of information”. Hedonic value and risk-avoidance value belong to this category. The second level is “the basic information value” with a cumulative percentage ranging from 70% to 80%, including utilitarian value and social value. The third category which only contains self-actualization value is called “the relationship information value”, as is shown in Figure 1.

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Conclusions and Discussions

This paper studies the composition of the tourism information value and the degree of its importance based on the tourists’ perception. Through factor analysis, five factors were identified from tourism information value: hedonic value, risk-avoidance value, utilitarian value, social value and self-actualization value. The finding of hedonic value, risk-avoidance value, utilitarian value, social value coincides with previous findings by Mi-Hea Cho (2008) [13] , which suggests that tourists in China and abroad share some common features in terms of tourism information value perception. Yet, another unique value called self-actualization value was extracted in this research, indicating that different social and cultural background may have an effect on the value perception.

According to different degree of importance, the tourism information value was divided into three hierarchical levels, namely, the core value of information, the basic information value and the relationship information value, while tourists consider the risk-avoidance value as the most important one. However, according to Hirschman & Holbrook (1982) [11] , compared with risk-avoidance value, hedonic value was attached much more importance to by western tourists, which may be relevant to various social and cultural background or the different maturity levels of tourists.

5.2. Implications

In practical terms, the findings of this study can be useful to marketers in creating promotional campaigns, providing them with a better understanding of what information appeals to their markets. To be more specific, on the one hand, the tourism companies and administrations should rethink tourism marketing by overall considering the five aspects of tourism information value, as all these values are being laid emphasis on by the tourists. On the other hand, tourism marketing should be more customized according to different importance level. For instance, the result shows that the information about risk-avoidance was ranked the most significant for the tourists, thus information on physical risk and financial risk should be paid special attention to in order to satisfy

Table 4. The importance of tourism infomation value.

a. The overall percentage may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Figure 1. The hierarchical structure of tourism information value.

this need. In this way, the tourism management efficiency can be improved and the limited marketing resources can create more value for both marketers and tourists.

Acknowledgements

This paper was financially aid by ZTE Tourism Research Institute and Tourism Research Center of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Cite this paper

Zhaoming Deng, (2016) Tourism Information Value and Its Hierarchical Structure. Open Journal of Social Sciences,04,10-16. doi: 10.4236/jss.2016.48002

References

- 1. Wu, N. (2007) Information Dissemination: A Key Link in the Marketing and Service of Tourist Destinations. Tourism Tribune, 22, 67-70.

- 2. Lurie, N.H. (2004) Decision Making in Information-Rich Environments: The Role of Information Structure. Journal of Consumer Research, 30, 473-486.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/380283 - 3. Wang, W.Z. and Yu, W. (2009) An Analysis of the Impact Mechanism of Scenic Area Websites’ Function on Browsers’ Behaviors: An Empirical Study Based on Student Tourists. Tourism Tribune, 24, 52-56.

- 4. Cees, G. (2000) Tourism Information and Pleasure Motivation. Annals of Tourism Research, 27, 301-321.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00067-5 - 5. Diehl, K. and Zauberman, G. (2005) Searching Ordered Sets: Evaluations from Sequences under Search. Journal of Consumer Research, 31, 24-32.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/426618 - 6. Vogt, C.A. and Fesenmaier, D.R. (1998) Expanding the Functional Information Search Model. Annals of Tourism Research, 25,551-578.

- 7. Rokeach, M. (1973) The Nature of Human Values. Free Press, New York.

- 8. Wen, J. and Gong, H.L. (2007) A Study on the Different Tourists’ Demands for the Information of Destinations: Taking Beijing as An Example. Tourism Tribune, 22, 18-22.

- 9. Holbrook, M.B. and Hirschman, E.C. (1982) The Experiential Aspects of Consumption: Consumer Fantasies, Feelings, and Fun. Journal of Consumer Research, 9, 132-140.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/208906 - 10. Van Raaij, W.F. (1986) Consumer Research on Tourism: Mental and Behavioral Constructs. Annals of Tourism Research, 13, 1-9.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(86)90054-X - 11. Hirschman, E.C. and Holbrook, M.B. (1982) Hedonic Consumption: Emerging Concepts, Methods, and Propositions. Journal of Marketing, 46, 92-101.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1251707 - 12. Dimanche, F. and Samdahl, D. (1994) Leisure as Symbolic Consumption. A Conceptualization and Prospectus for Future Research. Leisure Sciences, 6, 119-129.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01490409409513224 - 13. Mi-Hea, C. and Soocheong, J. (2008) Information Value Structure for Vacation Travel. Journal of Travel Research, 47, 72-83.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0047287507312422 - 14. Guo, X.L. (2008) Study on Tourists' Information Search Behavior before Tour. Master’s Thesis, Xiamen University, Xiamen.