Open Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation

Vol.2 No.2(2014), Article ID:46389,13 pages DOI:10.4236/ojtr.2014.22011

Torture in Honduras: Therapeutic Experiences of 2007-2008 and the Aftermath of the Coup

Arely Alvarado

The Center for Prevention, Treatment and Rehabilitation for Torture Victims and Their Family (CPTRT), Tegucigalpa, Honduras

Email: psicoarely@yahoo.com

Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 3 March 2014; revised 18 April 2014; accepted 27 April 2014

Abstract

Background: The Center for Prevention, Treatment and Rehabilitation for Torture Victims and their Family (CPTRT) participated in the “Professionalization facilitated through training in key healthcare services for torture victims” project coordinated by the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims (IRCT). Centers like CPTRT are typically created and run by small groups of healthcare professionals and human rights activists, often at great personal cost and risk [1] . The purpose of the project was to document the physical and psychological damage caused by torture as well as the results of the medical and psychological therapy. It also addresses: the socio-demographic profile of the victims, methods of torture and/or cruel, inhuman and degrading (CID), treatment, causal factors, and treatment effect. Material and Method: Psychometric and non-psychometric techniques were applied in order to obtain a baseline of the victims’ state of mental health, socio-demographic background, clinical and torture exposure, as well as evaluating the impact of the medical-psychological therapy at three and six months, respectively. The sample of torture victims is presented by the use of descriptive statistics and the effects during the study are presented with repeated measures analysis of variance. Results: The victims mostly experienced depression and anxiety and to a lesser extent, post-traumatic stress and somatizations as a response to the traumatic events they endured. The analysis demonstrates a significant drop in symptoms over the six months of the study in those victims who participated in the entire project. Conclusion: Although the several limitations and unforeseen situations arose in a study of this type, a holistic, multidisciplinary and systematic approach is able to decrease disorders moderately, but not without taking into account the sociopolitical contexts and the obstacles appearing therein, which should also be considered and studied through triangulated methodologies that provide a broader perspective for exploring a complex phenomenon like torture. Therefore, a standard rehabilitation program is neither possible nor desirable in the field of torture treatment (this is amplified in a political context of a coup).

Keywords

Torture, Violence, Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment, Post-Traumatic Stress, Depression, Anxiety, Somatization, Human Rights, Medical-Psychological Treatment

1. Introduction: Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

When talking about torture, one can see that there are several different concepts that define the term more or less broadly. However, the fact remains that torture includes both physical and psychological methods that cause pain, harm and damage the social fabric.

Historically, torture has been associated with the judicial sphere, because in antiquity, the Middle Ages and until the end of the 18th century, judicial torture was a part of regular judicial proceedings. As Pierre VidalNaquet stated, “Torture is nothing other than the most direct and most immediate form of the domination of one man over another, which is the very essence of politics.” (Interamerican Institute of Human Rights (IIHR, 2007))

However, this situation took a dramatic turn with France’s Declaration of the Rights of Man, which was influential throughout Europe and the rest of the world because it supported the abolition of torture. This leads directly to the United Nations General Assembly’s adoption on December 10, 1948 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights1, which was clearly stated in Article 5: “No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”

In this regard, the most commonly used definition for torture is contained in the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment—UNCAT, approved by the United Nations General Assembly on December 10, 1984. It defines torture as:

…any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions. (United Nations Centre for Human Rights, 1989, pg. 17) [2]

However, Amnesty International’s definition of torture is perhaps more simple: “Torture is the systematic and deliberate infliction of acute pain in any form by one person on another, or on a third person, in order to accomplish the purpose of the first against the will or interest of the second.” (IIHR, 2007)

Thus, one must consider that torture is associated with spheres of power and has the purpose of extracting information or exposing victims to physical and moral castigation. “Torture is about domination, above all of those who threaten to break the rules of their submission.” [3]

These conceptualizations reflect some differences, but the bottom line is that they are all prohibited without exception by international law, per a global consensus, even in times of war and other public emergencies.

The Swiss psychologist Westin (1994) [4] expressed similar ideas:

To those who utilize torture, it is one of the weapons—instruments—used against others to exercise the oppression of those who think differently, of political adversaries, and not infrequently, of religious and ethnic minorities. Torture is, therefore, an instrument suited to those who exercise power. In the view of the powerful, the act of torture is transformed into something trivial. (pg. 9)

Westin adds that the torturer acts, in other words, as a representative of the forces that have a decisive influence over the state machine. Regarding torture’s purpose, Westin states: “While torture shatters one’s personal identity, its main objective is to end collective movements. We see individuals who are psychically torn apart, but what is difficult to gauge is the damage that is done to the collective movement.” (pg. 14)

Thus, the purpose of torture is not to kill the victim; its ends are more repressive, more controlling, via the pedagogy of terror [5] . The main objective is to debilitate, drive to despair or cause the victim, to loss their identity and dignity. Another goal is to increase fear, panic and terror in order to paralyze the person in his or her social or political activities. In this sense, the methods of physical torture are the easiest to detect and analyze; however, the psychological methods are more subtle and may have an individual, family or collective character, focusing on one aspect of the person’s life or even several. These may range from blackmail and death threats to the person or person’s family to sensory deprivation, intimidation, persecution, humiliation, simulated shootings or killings. They may even include more sophisticated forms of torture based on modern technology, like the use of chemical substances, slow-acting drugs, prolonged side effects from radioactive substances, radiation, noise, etc.

In this way, while torture is prohibited and condemned under international treaties, for example, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Geneva Convention and the UNCAT, it still continues to be highly prevalent in today’s world. Figures about the prevalence of torture are difficult to obtain, because torture takes place behind closed doors and is denied by state authorities; however, the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims (IRCT, 2005) [6] estimates that torture is being practiced in over half of the world’s nations.

2. Torture and Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment in Honduras

In Honduras, the torture and CID treatment has been used as a mechanism of controlling society since colonial times. Although in 1981, Honduras returned to a democratic process after 20 years of military dictatorships, this return of power to the civil society did not mean respect for the constitution and human rights. On the contrary, it was in this time when country experienced the United States National Security Doctrine, which was already applied in South America [7] .

The doctrine included systematic violations of human rights carried out in the country in a selective manner. The most emblematic violations were torture, political killings and enforced disappearances. Therefore, the 80s are often called “the lost decade” in Honduras. It was a time in which hundreds of human rights violations were committed, and political crimes were common place. Thus, the torture situation in Honduras has been made invisible by the state and civil society since the 80’s, with the lost decade, covered by a big shadow of impunity, which complicates the fight to prevent and eradicate it.

The article 68 of the Honduran Constitution itself prohibits torture, adding that every person has the right of respect with regards to his or her physical, psychological and moral integrity. Honduras has reinforced this commitment by signing treaties2 like the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the UNCAT (reflected in Article 2.2), as well as the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT); treating torture as a crime against humanity, without exceptions. However, through its work, the CPTRT has documented, during its 19 years of work that torture continues to be a problem in Honduras. Torture is frequently carried out in three different circumstances: at the time of detention; when detainees are being transported; and after transportation to the places of detention themselves, which are sometimes unauthorized locations. The torture methods, are characterized by: blows, threats, verbal mistreatment, simulated executions, starving, suffocation, sleep deprivation, isolation, and to a lesser extent, burnings, shootings (even to the extent of incapacitating the victim) and sexual abuse; employing the torturer’s body, firearms, sticks, hoods, handcuffs, cigarettes or fuel as part of tools. The perpetrators are—in most cases—the National Preventive Police3, the Cobra Police4 and the military.

It is noteworthy that in all these cases, the torturers have gone covered with the most obvious impunity. There are cases in which victims become imputed in judicial processes driven by the Public Ministry, which are fraught with procedural irregularities that seek to accuse and convict the same victims of crimes without any basis. These supposed crimes have undertones of a political nature and/or a simply abuse of power state. This demonstrates a clear lack of will and effectiveness on the part of prosecutors from the Public Ministry, either by action or omission, raising the corruption and impunity in Honduras to ever higher levels [8] .

In a country like Honduras, it has been written about the social and political conflicts like the lost decade, although not in a highlighted way. Nevertheless, when it has been written about victims from torture and CID treatment, it has been mainly reduced to the legal aspects, without giving importance to the mental health part. The torture and CID treatment produces significant somatic and psychological effects. In some cases there is a delayed in the appearance of symptoms, while in others they are prolonged indefinitely and associated with the appearance of other health problems. Therefore, this paper sets out to highlight the importance of medical and psychological attention to the victims and their families, as the legal services are not enough to heal. It is also important to find out the effects of medical and psychological treatments in the bio-psychosocial life of the victims, in a country like Honduras, where torture has been kept in silence and behind doors, or in the worst scenario, where has been accepted due to the manipulation of the groups of power and the Media.

However, it is relevant to point out that this study was divided—unforeseen—into two phases, before and after June 28th, 2009, when there was the overthrow of the democratically elected president Manuel (Mel) Zelaya, and the disruption of the democratic processes within Honduras.

In this regard, there were special features that differentiate it from previous ones in Honduras and the rest of Latin America; one of the most important was the global condemnation of nearly the entire international community that the overthrowing of the government qualified as a military coup and that it was perceived as a threat to the stability of many Latin American governments.

In the post-coup, the above scenario discussed—the perpetrators, the victims, physical and psychological consequences and, in general, the work of the state—has been amplified, significantly and alarmingly, as the pedagogy of terror that was established during the “lost decade” is reactivated with the addition of some new nuances and ways of repression.

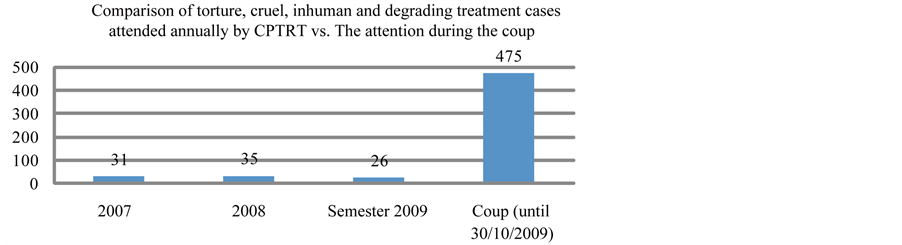

Figure 1 summarizes the time between 2007 and 2008, when the CPTRT documented thirty cases of torture and CID, much less than the figure recorded during the four months in which the de facto-government remained in power. In other words, during the period from 2007 to the first half of 2009, the CPTRT treated an average of 2.5 cases of torture a month, compared with 118.75 cases per month that have been treated since the coup [9] .

Due to the Coup, the Organization of American States General Assembly decided, in extraordinary session on July 4, 2009, to suspend the State of Honduras’ right to participate in the organization. Furthermore, the Interamerican Commission on Human Rights (IACHR, 2009), visited the country from 17 to 21 August 2009, and stated that in Honduras, in the wake of the coup, there were serious human rights violations, such as the arbitrary declaration of emergency rule (constitutional 1228 persons were arrested illegally, of which half (619) were minors), suppression of public demonstrations through a disproportionate use of force, criminalization of social protests, arbitrary arrests of thousands of people, CID treatment, increased militarization, an increase in situations of racial discrimination, violations of women’s rights, serious arbitrary restrictions on the right to freedom of expression and serious political rights violations, including torture and deaths.

The IACHR also found the ineffectiveness of legal frameworks to protect human rights, which was more pronounced during the coup [10] .

In general, all forms of violence in Honduras were and continue to be legitimized by the highest levels of economic and political power.

3. Method

The Integral Health Area of the CPTRT conducted a study over a period of 6 months from 2007 to 2008 that included 79 victims who were direct and indirect victims of torture or CID treatment. The information was obtained directly from the victims through medical and psychological interviews, which sometimes included a deposition for legal purposes (services were also provided on those occasions by the same center). Medical and psychological interviews, followed by medical and psychological assessments, were conducted in adherence to the diagnostic criteria of the DSM-IV5 thus obtaining a baseline that provided parameters for comparison with the third and sixth month of medical and psychological care, for the purpose of measuring the effectiveness of the treatment provided.

3.1. Assessment Tools

Considering the various valid internationally recognized tools for diagnosing psychological disorders or their aftereffects adhered to the diagnostic criteria of the DSM-IV, at the first place, a standardized intake questionnaire was developed, as well as a follow up questionnaire to be taken after three and six months respectively.

The data was also collected on socio-demographics, torture and/or CID exposure and its consequences, as well as the clinical needs of the victims. This resulted in the initial use of a general interview that considered the

Figure 1. Comparison of torture, cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment cases attended annually by CPTRT vs. the attention during the Coup. Source: CPTRT- 2009—“Torture: Systematic Repression after the Coup” (frequencies correspond to the direct victims of torture—not their families).

individual case and context of the tortured and/or mistreated person. This including a series of questions that addressed the concept of body-mind-spirit and culture in order to understand the expression of the traumatic episode in each victim. It also involved the collection of general socio-demographic data.

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), a self-applied questionnaire of 21 items that evaluates a broad spectrum of symptoms of depression, was also used. Its content places more of an emphasis on the cognitive components of depression, symptoms of a somatic/vegetative nature are grouped into a second block and given a greater weight. The English version was adapted to Spanish and validated in 1975, 1979, and 1991 respectively, and it is a well-recognized tool for evaluating the seriousness of depression.

The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ), a scale that measures the prevalence of criteria for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and exposure to trauma, was also used.

Finally, the Camberwell Assessment of Need Short Appraisal Schedule (CANSAS), which is employed as a part of standard clinical practice to identify the victim’s needs, was used in the investigation during the final month in order to evaluate needs in 22 social and health-related areas. It consists of 21 multiple-choice self-report questions, designed for people over 13 years old.

3.2. Sample

The sample was treated by the health area team within their communities as well as at the CPTRT itself, and were found through a search conducted by the institution or through reports and announcements in the mass media. However, in most of the cases, self-referrals were sought out the center through their own initiative. The victims were treated and followed up at the three and six months following their initial presentation at the center or following the visits from the health area team in the cities they lived.

Notably, the initial sample was of 79 persons, excluded from this study were children under the age of 14-, although they were included in the care provided—but by the first evaluation it had dwindled to 28 people, and by the final evaluation, it consisted of only 17 people. The sample was non-probabilistic.

Victims leaving the study resulted from abandonment of the therapy due to several underlying reasons. These were: difficulties in mobilization of the victims due to the lack of economic resources, the lack of economic resources for the transportation of the integral health team, the geographical remoteness of the communities, killings, abandonment of the treatment due to the fear of retaliation, and for preserving the safety of the integral health team.

3.3. Geography

The victims belonged to the communities of El Guantillo, San Sebastián, Ojo de Agua, Palillos, Jardines de la Sierra, Vallecito, Santa Bárbara, Tocoa, Rio Buey, Tela and Tegucigalpa, as well as the National Penitentiary and the Prison of Nacaome6.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

The socio-demographic data as well as the data extracted from the psychometric testing that was proposed were placed on a spreadsheet in order to create a preliminary baseline that referred to the 3rd and 6th months of treatment, respectively, and from which the analysis of the quantitative data proceeded by using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS—Version 10). This allowed obtaining descriptive and inferential statistics for the variables and scales.

Lastly, changes in the number of symptoms, depression and PTSD over time were examined using repeated measures analysis of variance. Frequency distributions and descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables and scales.

3.5. Medical-Psychological Care

The psychological approach was based mainly on two therapeutic standards, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and logotherapy however, in other cases the center worked on the level of brief therapy, or a combination of counseling psychology and legal services.

The medical approach was also based on two standards, one consisted of alternative medicine—homeopathy, and the other of conventional medicine. The most frequently used homeopathic remedies were: natrium muriaticum, cuprum metalicum, valeriana officinalis, arsenicum album, coffea cruda, rhus tox, kalibicromicum, vegetable charcoal, ignatia amara, and mercurio solubilis. In addition, plant essences like: energy extracted from plants and flowers, olive, rescue remedy, gorse, sweet chestnut, mimulus, scleranthus, and ceratum.

Also, within the school of conventional medicine: analgesics, anti-inflammatory, antibiotics, antimycotics, antidepressants, and ophthalmic, dermatological, and wound cleansing remedies were most frequently utilized, as well as referrals for specialized care in areas such as radiology and physical therapy.

During the assessments, a series of psychological questionnaires were applied for the purpose of learning and determining the therapeutic responses to the approach, and the response itself was evaluated based on the following criteria: 1) clinical recovery: complete disappearance of symptoms; 2) clinical improvement: reduced intensity and frequency of clinical symptomatology; 3) failure of the treatment: no improvement after treatment has been completed.

4. Results

4.1. Socio-Demographic

From the total sample of 79 victims of torture and/or CID treatment, 30% were women and 70% men, ranging from 15 to 79 years old, where the mean was 40 years old. All were Honduran and 97% were catholic/Christian. Most of them were living with a partner (65%) whether they were married or unmarried, and with an average of 3 children per family. 14% of them were located at the penitentiary center and 83% lived at their respective homes. 79% was entitled to work and 58% had a job in the informal sector, while the remainder were mainly homemakers or imprisoned.

It is worth noting that 14% of the victims were detained in a police station at the time of the study, 25% were in prison and 38% had legal proceedings pending during the course of the study. In relation to any type of social support, only 4% were generally isolated from support.

The CPTRT, in addition to providing medical-psychological services, also offers other types of assistance, often concurrently; for example, 59% of the victims were also receiving legal assistance, while 23% were receiving social services from the center.

The level of education of this sample is represented in the Table 1.

4.2. Assessment of Torture and/or Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment

Within the range of the victims covered by the study, some of them had directly suffered torture and/or CID treatment, while others were witnesses or indirect victims.

The Table 2 is a breakdown of the number of victims who have directly suffered from traumatic events.

It is worth mentioning that these acts were mainly perpetrated by the police (87%), followed by the military (8%) and, on an insignificant scale, other perpetrators or state-sponsored institutions.

Table 1. Level of education.

Note: the level of education of the remaining 39% was not known.

Table 2. Prevalence of different types of traumatic exposure.

4.3. Head Injury

44% of the sample population experienced some kind of head injury, the most common was beating to the head, 8% experienced loss of consciousness, 1% experienced suffocation and 1% drowning.

4.4. Current Psychiatric Symptoms

Not unexpectedly, the symptom categories associated with anxiety disorders, PTSD and mood disorders are the most prevalent.

Table 3 is a breakdown of the psychiatric symptoms encountered with the victims of the study, in order of prevalence.

The level of substance abuse was at 10% of the sample population, this was mainly alcohol and tobacco abuse, and is a figure that was later confirmed in the CANSAS. Also, using the parameters proposed by the Beck Questionnaire I, the categories in which the population was situated were distributed as follows in Table 4.

The figures reflect that on average, the victims were experiencing slight depression, and that a small but still alarming percentage of the population was experiencing serious depression. Specifically, within depressive symptomatology, the following symptoms manifested themselves most frequently: sadness, 33%; changes in sleep patterns, 30%; difficulties in concentrating, 20%; and loss of sex drive, 16%. Other changes, including lack of energy, were at 13%.

Also, headaches, muscle and back pain, epigastric pain and itching predominated among the physical symptoms. There were relapses and intensification of comorbid chronic illnesses such as high blood pressure and diabetes mellitus in some victims, while others developed high blood pressure as a result of the situations to which they were exposed. Also, the prevailing organic morbidities were attacks of acute gastritis, high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, epilepsy, peptic acid disease, cardiac insufficiency, and bronchial asthma.

Table 3. Psychiatric assessment at initial presentation.

Table 4. Level of depression.

4.5. Mental Health Follow Up and the Tracking of Results

After the initial evaluation, in the third and sixth months of the study, respectively, the level of mental health and the impact of the medical-psychological treatment on the sample population were assessed.

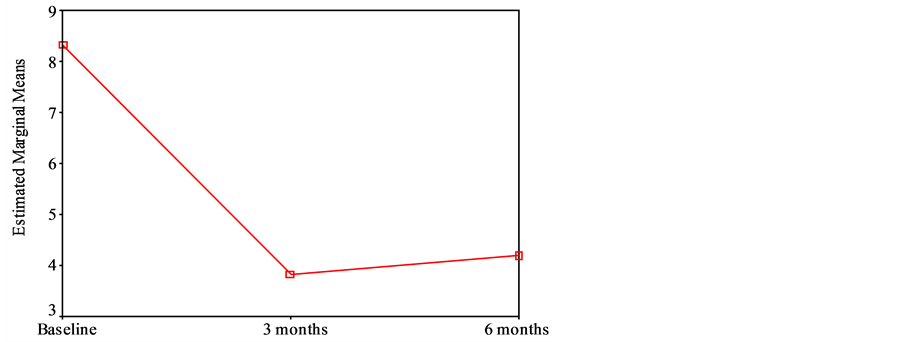

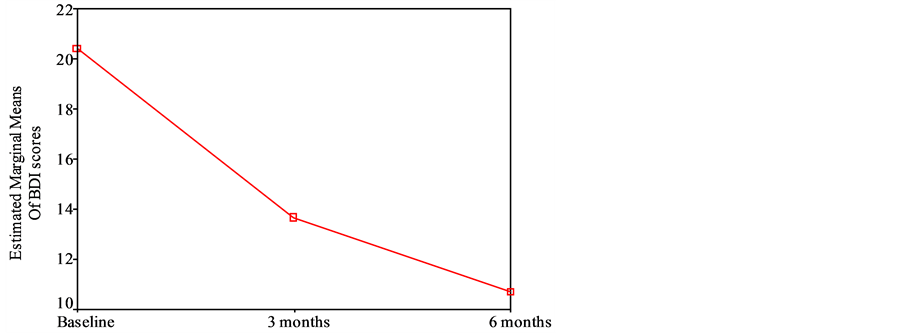

At a general level, tracking of the results suggests a modest recovery among the victims, because the average number of symptoms dropped significantly over the course of the therapeutic process (with the sole exception of: sluggishness, other emotional disorders and obsessive and compulsive phenomena, which increased). In the same way, measurements of depressive symptoms show similar significant drops for the BDI. These changes are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

These results should be interpreted with caution, as the cut off score is taken from international standards. These are usually not sensitive to the cultural sensitivities of the rural population. Nevertheless, the results also tell that a significant group of victims can benefit from medical and psychological assistance.

In order to measure the medical and psychological impact of the study, the data was taken from victims who were evaluated at the intake, 3 months and 6 months. In this way, it can be seen that the number of symptoms dropped significantly for these 16. In the intake the mean was 8.3, on the 3rd month the mean was 3.8 and the 6th month with a mean of 4.1.

Figure 2. Psychiatric symptoms and their follow up. Repeated measures analysis of variance, df = 2, MS = 99.75, p = 0.000.

Figure 3. Changes in mood disorders. Repeated measures analysis of variance, df = 2, MS = 421.1, p = 0.000.

In general, all this shows a significant impact obtained from the medical and psychological assistance given in a systematic period of time. Unfortunately, that was not the case for most of the victims who had to drop out the treatment (reasons explained above).

To measure changes in mood disorders, the data from 17 people who were evaluated at the intake, during the 3rd month and finally in the 6th month was used. Related to the previous results, the BDI mean for the intake was 20.4, when afterwards, in the 3rd month it decreased significantly to 13.6 and even in the last measurement, in the 6th month got 10.7, again, the results are significant.

These results seems to show a strong correlation between improvements from the medical-psychological level when care is given in a systematic manner with commitment and dedication. In some areas the improvements were modest and slow, but in a few others, recovery was satisfactory.

However, one may note that in most cases, the changes did not come with positive social changes, this was shown with the evaluation of the psychosocial dimension, and the results reflects an opposite trend over the course of the process, because while there were improvements in some psychological and physical variables, these emerged in contrast with aspects that worsened over the course of the study. These included economic and housing conditions, as well as benefits and the lack of justice (social aspects).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The medical-psychological care provided by the Integral Health area of the CPTRT, accompanied on some occasions by legal and social assistance, has always been given in difficult physical, political and social contexts.

In relation to this study, a significant number of drop outs were experienced due to several reasons. The first was due to having to travel long distances and the scarcity of economic resources (on both sides); another reason was exacerbated by the simmering conflict that has prevailed in the country, which covers up torture as a tool used by the state, and thereby hinders recovery. It also prevents a means of accessing a safe haven for treatment. It is a situation that forces many victims to abandon the process due to terror or threats of greater retaliation. Threat of life was a reality for the victims as well as for the human rights organizations working with them. Another reason is that when treatment takes place in the prisons, prisoners can be killed or transferred to another place of detention that is far away and difficult to access. These are just some of the reasons why there are always limitations in this type of study in the torture field. At the same time, it clearly reflects the realities on the ground in the countries that experience torture and CID treatment. They are far away from the controlled scenarios of the assistance and research of developed countries.

However, this situation in Honduras has gained a degree of visibility, even though the outlook is still dark-, because torture and CID treatment have been systematic and at times quite brazen since the June 28, 2009 Coup. These acts have been documented and made visible at the national and the international level.

Therefore, this study can be viewed as a preliminary study, not because it lacks validity, but because in this particular type of study, unforeseen events such as desertion, rejection due to fear, etc. are a constant. This makes it impossible to generalize the scope of the problem. Therefore, it is necessary to include other reflective components, perhaps a greater qualitative analysis, in order to establish a greater understanding of the consequences of torture from different perspectives, or from a subjective standpoint, where one can, wherever possible, really find out which factors, other than medical-psychological assistance help heal the individual, as well as the social fabric. It is necessary to find out more about the reasons why some victims become resilient protagonists of new battles while others do not succeed and live the rest of their lives marked by the pain of their history.

Data can also play a crucial role in the prevention of torture through documenting allegations and evidence of torture and advocacy work. In addition, it is necessary, to undertake more theoretical and critical reflections on this type of study, beginning with asking whether the diagnostic criteria used universally should apply equally to regular day clinic victims—most of whom suffer from disorders in their mental processes or subjective conflicts that are far removed and have no relationship whatsoever to violent historic, political, social and cultural events —as well as to the victims, who develop symptomatology as the result of external factors, unlike the former. These reflections are important in order to avoid the trap of positivist reductionism, which when speaking about psychology is, as Nietzsche said [11] “Transformed under the influence of positivism, into an arid landscape that has led many brilliant minds astray.” (pg. 7)

Here, we are not attempting to condemn positivism, but simply show that with an issue such as torture, it is insufficient; proof of this is that the taxonomic categories of the DSM-IV or ICD-107, among others, have not addressed any historical, political or ideological aspects within their diagnostic criteria, which would indicate that the established diagnostics do not fully apply to these victims, although they do give a glimpse of how devastating the consequences and effects of torture can be.

This same point has been amply discussed at the meetings of the Latin American and Caribbean Network of Health Institutions against Torture, Impunity and Other Human Rights Violations8 in 2001 (cited by Maradiaga, 2002) [12] , which has declared:

Torture is a political, not a medical event; its consequences for the subject can generate medical, psychological or psychiatric disorders, but these are not the only possible form of expression of damage in an individual. These health problems do not authorize one to speak of torture as if it were an illness; this would medicalize it, or address it in terms of diagnosing or treating the torture.

This clearly represents a challenge for healthcare professionals, because they are dealing with a multicausal phenomenon that manifests with many different nuances and consequences; therefore, it would be too much to aspire or attempt to reflect in quantitative data the true pain or suffering of these victims. Thus, one should discuss the symptoms in a manner that goes beyond the individual—one should also study and discuss “psychosocial symptoms”. As a School of Naval Mechanics survivor from Argentina (ESMA’s), once said, “Torture happened once, but lasts a lifetime.” [13]

Therefore, this study represents one more effort in the fight to increase the visibility of and eradicate torture and other human rights violations, since it documents the consequences and effects of torture on the Honduran population based on an evaluation of this population’s needs while receiving care and, where possible, in healing after living through this type of an event.

The process was a challenge, aspects like killings in penitentiary centers, intimidation of ravaged communities, the scarcity of economic resources, a false sense of improvement, fear, lack of safety for the health team to go into areas at risk, etc., which lead to a high dropout rate in the sample—a situation that should be considered when interpreting the results.

Another factor that made this process more complicated was the use of psychometric batteries which, despite the validity and reliability of these tests, is associated with traditional clinical spaces, not with spaces where care providers normally work in a country like Honduras, which can range from private homes to hammocks and outdoor settings, etc. However, these same factors are what also provide a real panorama of the socio-demographic profile, living situations, unmet needs, experiences and the daily routines of the victims.

The findings lead to the conclusion that the victims were mostly experiencing depression and anxiety and to a lesser extent, post-traumatic stress and somatizations as a response to the traumatic event they endured. The prevalence of head injury is a particular challenge in the rehabilitation of the victims. The clinical signs and symptoms encountered, as well as their frequency and changes, support the diagnostics. In some cases a pathological organicity existing prior to the trauma was intensified and relapses were induced in these victims; however, the response to the treatment and psychological therapy provided and the condition of the victims prior to the occurrence of the morbidity were key in determining the prognosis and improvement of their state of health.

The approach of some victims, who had greater ease of receiving medical-psychological assistance in a systematic manner, facilitated the process of care, diagnosis and treatment options for their families or support groups. Individualized care was given to each victim, who, in some cases, received psychological counseling once a week as well as medical care, evaluating the need for complementary therapy, the possible appearance of side effects, whether the psychopharmacological treatment had been effective, and the status of the comorbidity that was detected. Thus, the response to integral treatment was satisfactory in most of the victims who continued until the end.

In the months following the end of the program, clinical checkups of the victims were continued, and organic diseases were kept under control and treatment given within the resources of the center. Some of these responses were due to the characteristics of the premorbid personality of those who showed up for their doctor visits and psychological therapy sessions and attended treatment regularly.

Here, it is interesting and worth noting that Latin America’s history of human rights violations, and therefore, of human suffering, has given rise to multiple projects aimed at assisting and healing these victims, and there are publications that discuss how this process has gone. It has been successful at times, unsuccessful at others, but in the end, still offers points of correlation.

For example, in terms of consequences and effects, the Latin American and Caribbean Network of Health Institutions against Torture, Impunity and Other Human Rights Violations (cited by Maradiaga, 2002) found that almost throughout the entire region, the symptomatology of 70% of those affected by torture is concentrated in anxiety and depression disorders.

Along with this, another point of coincidence with investigations in the Southern Cone, is that the attitudes of sarcasm or indifference that some victims adopt can be twisted or misinterpreted by others as they are often the product of their survival instinct or defense mechanisms; as Robaina (2001) [14] from the Social Rehabilitation Service (SERSOC) center in Uruguay expressed: “Traumatic episodes, particularly torture, emerge but one cannot talk about them. On the clinical level, we observe a strong resistance to talking about them, and we often run up against hostile discourse.” (pg. 2)

Also, from the Argentine Team of Psychosocial Work and Research (EATIP) in Argentina, Kordon (1993) [15] , has observed, over the course of her work, an entire spectrum of responses to traumatic situations, stating:

While the emotional impact is always of a considerable magnitude, we occasionally do not see any pathological response; on the contrary, we have seen active behaviors of adaptation to reality, including in persons in which these behaviors would be otherwise unthinkable, due to various psychic and social factors. We do not believe that going through a traumatic experience will necessarily result in pathology, and when it does, there is a high degree of variability from one individual to the next. (pg. 32)

However, there have been cases with clinical consequences, with depressive symptomatology predominating, followed by symptomatology related to reliving the traumatic event.

In terms of what was revealed in the process of this study and in its results, it can be said, in the end, that the greatest disease encountered was the violence—in the words of Rojas (2000) [16] , “...the violence of the State is ‘more than violence’, it is the height of violence, because it produces a system, a power that occupies the highest positions of mankind in order to manage and apply it”, and it is done with impunity in a significant and alarming way. In light of this, Kersner (1992) [17] , prompt to ask ourselves, in what way can we speak of “healing” when the context of impunity is becoming stronger? What are the effects and consequences that this produces in the long term? At what point does impunity become bigger than the torture itself?9

Thus, in a positive manner, beyond the responses, this study raises some new questions. Also, raising awareness of the relationship between the environment and possession of land (a historic problem) and torture on the national and international level is a daunting challenge because before the coup, torture was mostly used in rural areas, arising from issues in the local environment or land-related conflicts.

To legitimize a world order that encourages respect for human rights, it is necessary to work on the local level without losing one’s view of the global. This implies empowering communities to exercise their civil rights, thus counteracting a culture of fear propitiated by the pedagogy of terror that brings with it silence, frustration, and worse still, resignation. The entities that must assume responsibility for doing it are many, as the ultimate goal is for everyone to see themselves as dignified human beings worthy of enjoying basic human rights.

6. Recommendations for Future Studies

1) Reproduce this investigation with a different epistemological approach than positivist, including different options for qualitative research, including but not limited to phenomenology, case studies, analysis of discourse and the processes of constructing discursive practices, which can also pass into the national collective memory without being lost over the passage of time.

2) Differentiate between patterns or behaviors derived from the prevailing patriarchal context (which is intensified in the rural sector) and those which are a product of the personality of the subject under study.

3) Determine the differences in the effect of the medical-psychological treatment in the victims with a criminal, political and landholding background.

4) Delve more into the issue of landholding as one of the main contexts in which torture presents itself.

5) Based on the qualitative data obtained, design strategies for local confrontation and empowerment that respond to the needs and vulnerabilities of affected populations.

Acknowledgements

This study was made possible thanks to the financial and technical contribution of the IRCT to the CPTRT. Dea Kopp Jensen, Hellen McColl, Sara Gjerding and Craig Higson-Smith from IRCT provided valuable inputs to the technical part. The CPTRT team of the Health Area, Eliomara Lavaire, Lucía Calidonio, and Carmen Martínez who gathered some of the data for this study.

References

- McColl, H., et al. (2010) Rehabilitation of Torture Survivors in Five Countries: Common Themes and Challenges. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 4, 16.

- United Nations Centre for Human Rights (1989) Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, and Degrading Treatment or Punishment. Methods of Combating Torture, Ed., Geneva.

- Committee for the Defense of People’s Rights—CODEPU (1989) “Persona, Estado, Poder” Estudios sobre Salud Mental en Chile 1973-1989 (“Person, State Power” Studies on Mental Health in Chile 1973-1989). http://www.derechos.org/nizkor/chile/libros/poder/index.html

- Westin, C. (1994) Tortura y existencia (torture and existence). Academy Universtity of Christian Humanism, Santiago.

- Otero, E. and López, R. (1989) La pedagogía del terror: Un ensayo sobre la tortura (The Pedagogy of Terror: An Essay on Torture). Atena, Santiago.

- International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims-IRCT (2005) The Struggle That Must Be Won. 20 Years with the IRCT. http://issuu.com/irct/docs/strugglethatmustbewon

- Rico, A., et al. (2009) Doctrina de seguridad nacional y políticas de contrainsurgencia en honduras (National Security Doctrine and Counterinsurgency Policies in Honduras). In: Feierstein, D., Ed., Terrorismo de Estado y genocidio en América Latina (State Terrorism and Genocide in Latin America), Prometeo Libros, Buenos Aires, 55-72.

- Association for a Fairer Society (2012) Honduras el país más corrupto de Centroamérica según informe de transparencia internacional (Honduras the Most Corrupt Country in Central America as Reported by International Transparency). http://asjhonduras.com/cms/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=136:honduras-el-pais-mas-corrupto-de-centroamerica-segun-informe-de-transparencia-internacional-&catid=61:transparencia&Itemid=78

- Centre for Prevention, Treatment and Rehabilitation of Torture Victims and their Families (2009) Tortura: Represión sistemática tras el Golpe de Estado (Torture: Systematic Repression after the Coup). CPTRT, Tegucigalpa.

- Interamerican Commission on Human Rights (2009) Annual Report of the Interamerican Commission on Human Rights 2009: Honduras. http://www.cidh.org/annualrep/2009sp/cap.4Honduras09.sp.htm

- González, F. (2006) Investigación Cualitativa y Subjetividad (Qualitative Research and Subjectivity). ODHAG, Guatemala.

- Maradiaga, C. (2002) Tortura y trauma: El viejo dilema de las taxonomías psiquiátricas (Torture and Trauma: The Old Dilemma of Psychiatric Taxonomies). Magazine Reflexión No. 28.

- Interamerican Institute of Human Rights (2007) Atención Integral a víctimas de tortura en procesos de litigio: Aportes psicosociales (Integral Care for Torture Victims Involved in Judicial Proceedings: Psychosocial Contributions). IIHR, San José.

- Robaina, C. (2001) Reparación desde lo terapéutico (Healing from the Therapy Perspective). Magazine Reflexión, 27, 27-31.

- Kordon, D. (1993) La tortura en Latinoamérica: Sus efectos inmediatos y mediatos (Torture in Latin America: Its Immediate Effects and after Effects). Magazine Reflexión, 19, 30-34.

- Rojas, P. (2000) Qué se entiende por tortura? (What Is Meant by Torture?) In: La tortura y otras violaciones a los Derechos Humanos (Torture and Other Human Rights Violations), ECAP-ODHAG-IRCT, Antigua.

NOTES

1See: http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/.

2See: http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/TreatyBodyExternal/Treaty.aspx.

3National Preventive Police: National Police apart from the army command through its organic law.

4COBRA Police: specialized police officers in riot and disturbances, snipers and tactical and special operations.

5Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition.

6The departments with the highest prevalence of torture and CID treatment (Colón, Santa Bárbara and Comayagua) had as the origin the problem of land tenure.

710th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems.

8CPTRT is one of the eighteen centers members of the Latin American and Caribbean Network of Health Institutions against Torture, Impunity and Other Human Rights Violations.

9For more about this see: “Paisajes del Dolor, senderos de Esperanza. Salud mental y Derechos Humanos en el cono sur” (Landscapes of Pain, Hope Trails. Mental Health and Human Rights in the Southern Cone) 2002. “Impunidad. (Impunity)”. (2nd Seminar of the Maule Region. Human rights, mental health, primary care: regional challenge) 1992.