Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.3 No.3(2013), Article ID:34951,7 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2013.33042

An ongoing concern: Helping children comprehend death

![]()

Caylor School of Nursing, Lincoln Memorial University, Harrogate, USA

Email: sandra.mcguire@lmunet.edu, logan.mccarthy@lmunet.edu, marvanne.modrcin@lmunet.edu

Copyright © 2013 Sandra L. McGuire et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 24 April 2013; revised 24 May 2013; accepted 15 June 2013

Keywords: Children; Death Education; Anticipatory Guidance

ABSTRACT

This article addresses the need for anticipatory guidance about death and death education with young children. Children often experience the death of an immediate family member before the age of ten. This number increases if one considers the loss of friends, pets, and other loved ones. However, children experience a death with little or no anticipatory guidance or knowledge about death. Anticipatory guidance can assist the child in having a better understanding of a death when it occurs. Talking about death with children can be difficult for adults. However, it is important to address the topic and realize the impact anticipatory guidance in relation to death can have in assisting with childhood bereavement, anticipatory grief, and anticipatory adaptation. By providing anticipatory education related to death symptoms such as grief, anger, and/or fear, regressive or aggressive behaviors can be prevented or lessened when a death occurs. Age appropriate developmental levels for understanding the concept of death, resources for death education, and literature that can be used for death education are presented. Any resource used for death education with children should be carefully reviewed by the adult for its appropriateness prior to its use.

1. INTRODUCTION

Death is a topic that nurses, parents, significant adults, and educators are often reluctant to teach or discuss with children. What the well-meaning nurse or adult fails to realize is that, even for children, death is an inevitable part of life, and children often experience the loss of a loved one. This loss comes in many forms and can include family members, friends, significant adults, and pets. Children are regularly exposed to the concept of death as portrayed in contemporary media and in common occurrences such as the child seeing a lifeless bird or animal.

Providing support and anticipatory guidance for children, especially children facing a death experience, can help the child successfully cope and mitigate the negative health consequences of unresolved grief [1]. Avoiding the subject of death can create the potential for misunderstanding, anxiety, anger, depression, regression, aggression, self-guilt, and fear in children when a death occurs. With no anticipatory education on the subject of death, children can be at a disadvantage with a death experience.

2. ANTICIPATORY GUIDANCE AND DEATH

According to Mosby’s Medical Dictionary [2], anticipatory guidance is the “psychological preparation of a person to help relieve the fear and anxiety of an event expected to be stressful” [2]. Nurses use anticipatory guidance for “preparation of a patient for an anticipated developmental and/or situational crisis” [2]. Anticipatory guidance can be extremely important in helping a child prepare for a death experience. Anticipatory guidance can also assist in mitigating anticipatory grief and facilitating anticipatory adaptation. Anticipatory adaptation is seen as “the act of adapting to a potentially distressing situation before actually confronting the problem” [2].

3. SIGNIFICANCE OF THE PROBLEM

It is a common occurrence for children to have to deal with death. The following illustrates the immensity of the death experience with children [3]:

• One child in every seven will experience the death of an immediate family member by the age of ten.

• One child in twenty will have a parent die before he or she graduates from high school.

• 73,000 children die each year in the United States.

• Of those 73,000 children, 83% have surviving siblings.

These statistics are even more staggering if one includes the death of friends, significant others, and pets. The loss of a pet is often the first loss that a child experiences. Coping with death can be difficult for anyone, but it can be especially challenging for children.

4. RESEARCH: CHILDREN’S VIEWS ON WHEN TO TEACH ABOUT DEATH

Although extensive research on the subject could not be located, two studies were found that looked at children’s views of when to teach about death. Jackson & Colwell [4] conducted a study in the United Kingdom among school age children ages 14 to 15. Two hundred and fifty students completed a 15 question paper dealing with attitudes related to being taught about death in school. Sixty-five percent of the students believed that the topic of death should have been introduced at primary school, 58% of the students believed death should be taught as a subject in school, 51% of students reported they would prefer to talk about death with parents rather than in school, 62% of students reported that it would be better to talk about death than to avoid it, and 58% of students reported they wanted to know more about death [4].

Bowie [5] conducted a small scale research study to determine students’ and teachers’ views on the subject of death education in school curriculum. The research study included a sample of two non-denominational schools with a total of 107 pupils, 74 teachers, and 4 student teachers. The study addressed two questions: 1) if dying and death were something the student thought about; and 2) if the topic of death was something the student wanted to learn about in class [5]. The results verified that 73% of the students stated that death and dying is a topic they think about [5]. The study also supported the belief that a curriculum teaching death and dying needs to be developed to assist in educating students prior to the occurrence of a death [5].

5. TEACHING CHILDREN ABOUT DEATH

When teaching children about death, there are several important aspects to consider. What is said to children about death takes into consideration the child’s age, developmental stage, and experiences [6]. Major aspects relative to the child’s understanding of death include the irreversibility factor, finality, inevitability, and causality of death [1]. Comprehension of time, finality, life cycle with natural processes, and causal relationships are all acquired during different developmental stages [7].

Anticipatory guidance with children in relation to the concept of death is appropriate. However, when to actually begin teaching children about death has not been determined. The seminal, classic works of Piaget [8] and Nagy [9] suggest that the age of eight is an appropriate time to begin formal teaching about death. It is generally acknowledged that by age eight, most children have an understanding that death is final and irreversible [4]. Research by Vianello & Marin [10] noted that by the age of four or five children appeared capable of having an understanding of death.

In the book My Grandson Lew [11] a young grandson is sharing happy memories of his grandpa with his mother. The young boy explains that he had been waiting every night for grandpa to come back and asks his mother why grandpa used to visit but now does not come. The young boy had not been told that his grandfather had died. The young boy’s struggle with trying to determine why his grandpa was no longer there brings up the issue of deciding when it is appropriate to tell a child about the death of a loved one, the role that anticipatory death education can play in assisting families and caregivers addressing such death experiences, and the struggles that a child may have in wondering why the loved one is gone.

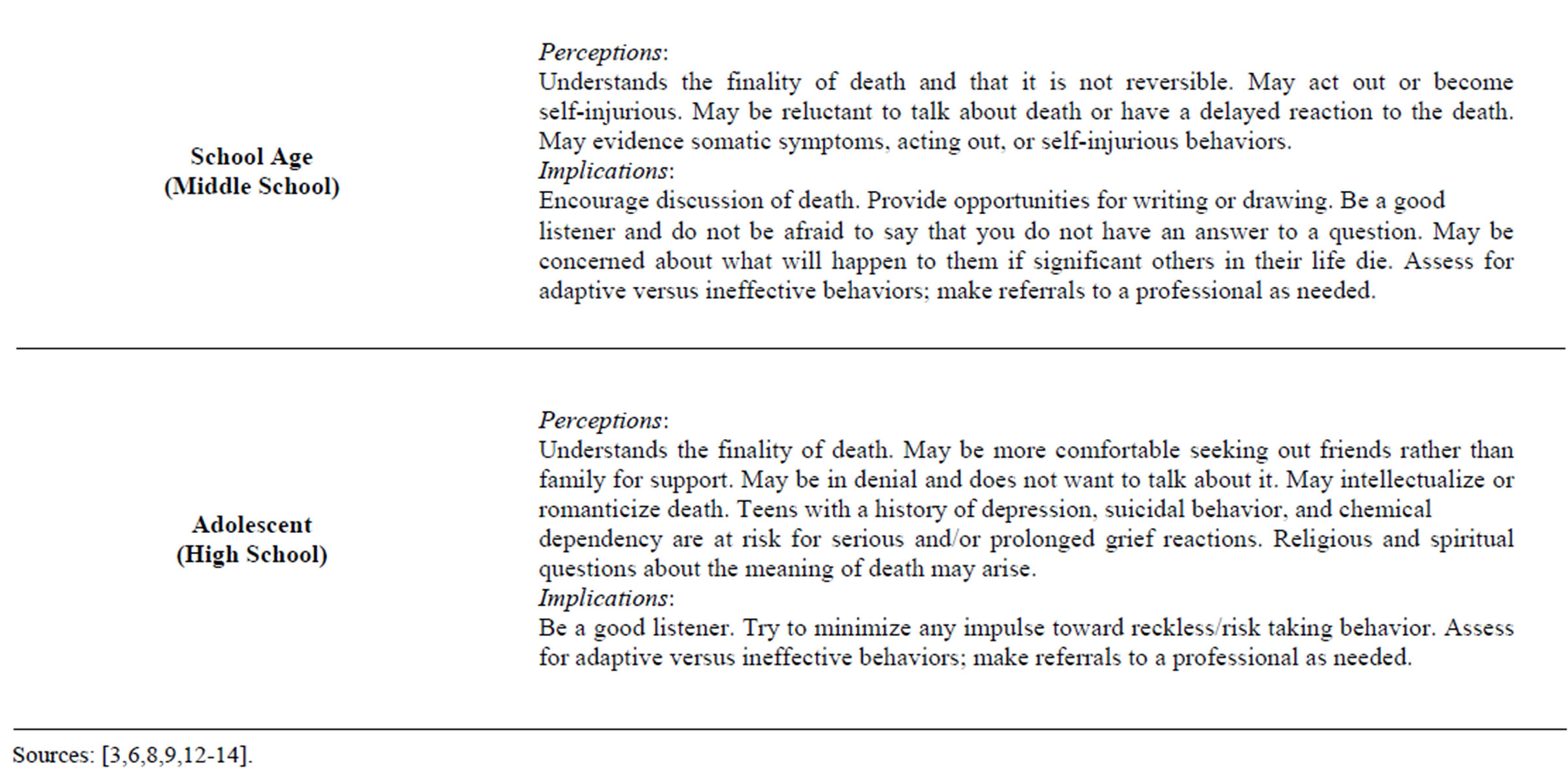

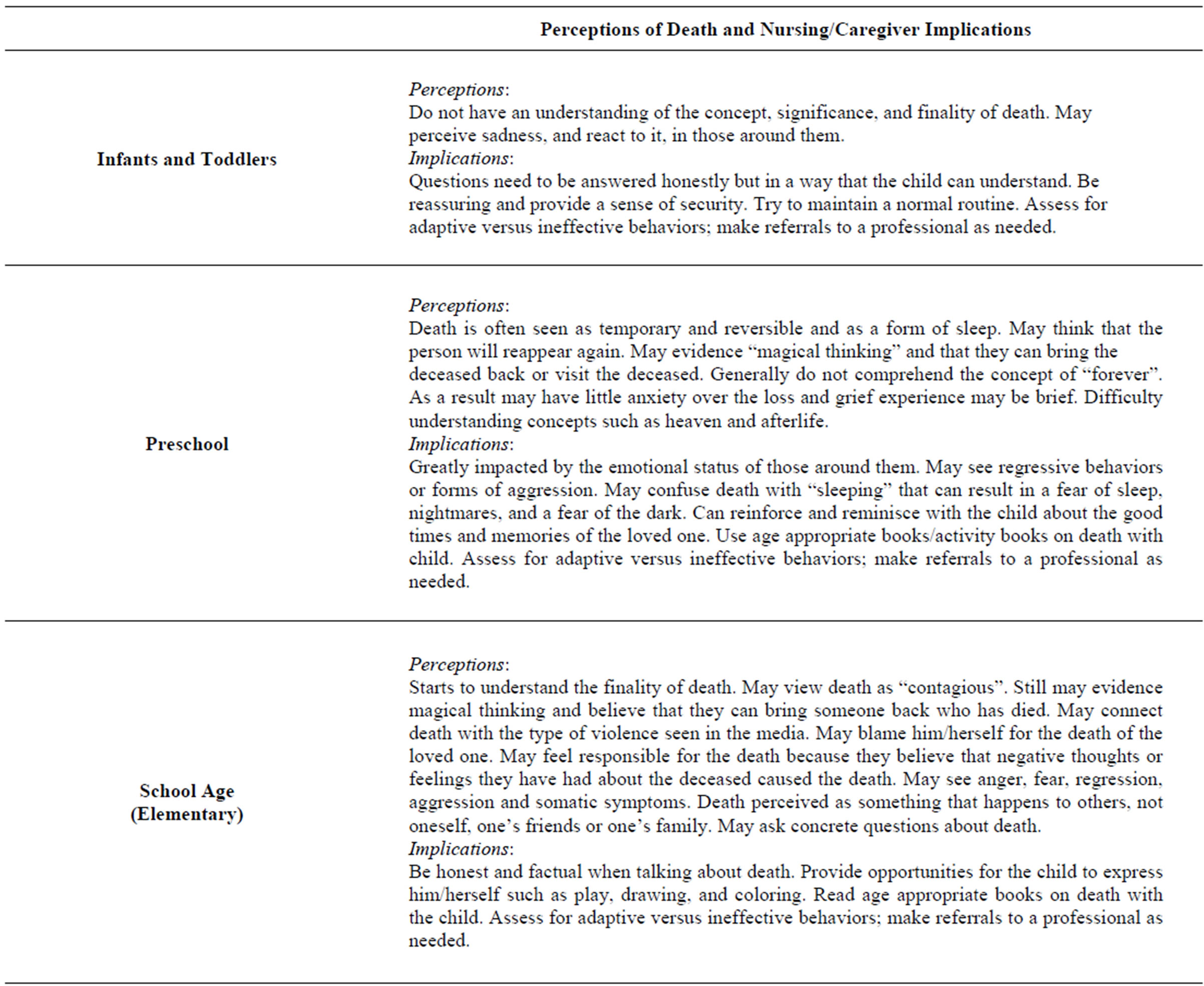

Table 1 examines developmental stages and the perceptions of death by age group and presents implications for death education for nurses, parents, caregivers, and other adults who work with children. Irrelevant of age, it is important to answer children’s questions about death as they arise. “By talking to children about death, we may discover what they know and do not know; if they have misconceptions, fears, or worries” [6]. Nurses and other adults can help prepare children for experience with death and assist them in their ability to cope with the grieving process. It is important, especially with young children, not to discuss death in terms of “gone to sleep” or “gone away” as this can present issues for the children including being afraid of sleep, not sleeping, afraid of the dark, wondering why the person went away or experiencing self-guilt assuming they are responsible for the loved one’s absence.

The information in Table 1 is generalized to age groups. It is important to remember that children within the same age group are unique in their understanding of death and the corresponding grief response [12]. It is critical that the nurse assesses the family history and understands the impact that previous experiences may have had on the child (e.g. the death of a sibling, parent, grandparent, friend, or pet). Furthermore, it is imperative for nurses to recognize the need for, and encourage the use of, professional counseling for the child as needed.

6. UNDERSTANDING DEATH: CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

Children’s literature is an effective way to introduce the concept of death to children. Corr [15] noted that books

Table 1. Developmental stages and perceptions of death developmental stage.

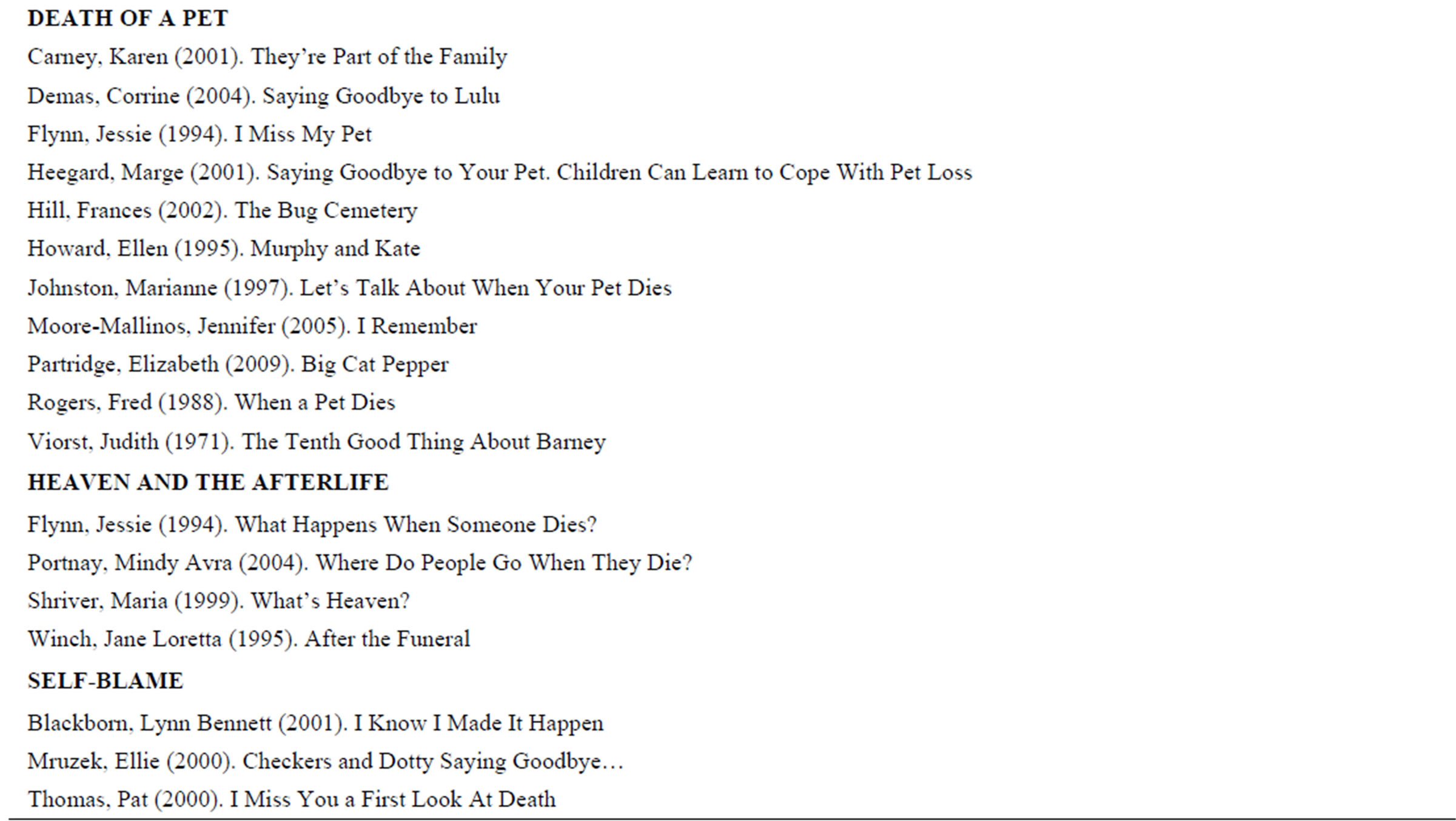

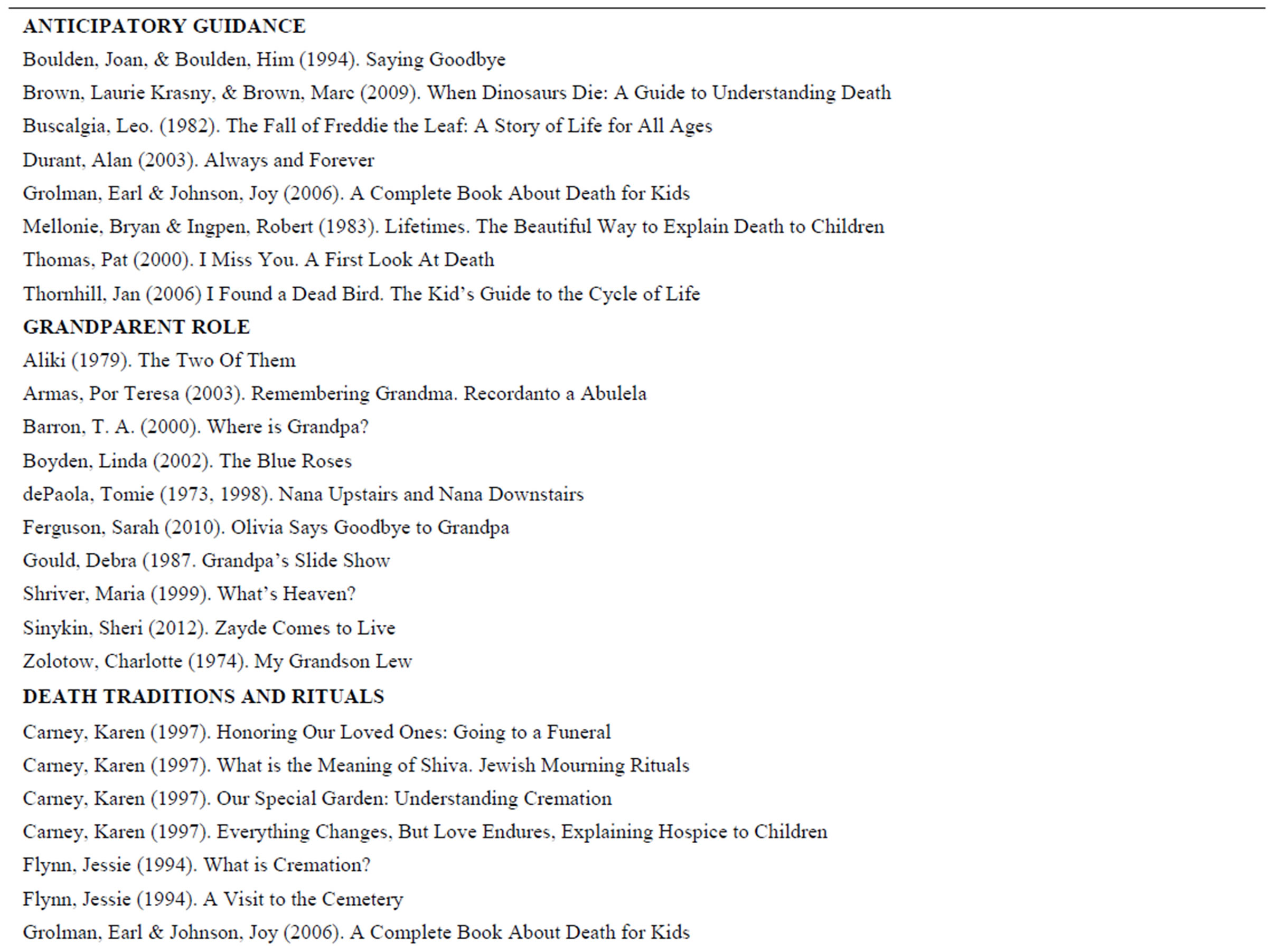

aid with understanding the implications and meaning of death and can be used in an anticipatory sense to explore the topic of death. Children’s literature, especially early children’s literature, plays a major role in attitude formation [16,17]. It is important for the adult to be available to read through the book with the child, honestly answer questions that arise, and not be afraid to say they do not know the answer. Before sharing a book with a child on death it is important to review the book for its appropriateness. A listing of books covering the topics of anticipatory guidance, death of a grandparent, death traditions and rituals, heaven and the afterlife, the death of a pet, and self-blame is given in Table 2.

In her article, Torbic [3] provided several literature resources for discussing death and grief with children and divides the literature into sections appropriate for the reader. Sections included information for young readers, middle and teenager readers, readers affected by suicide, and guidance for professionals such as nurses.

6.1. Anticipatory Guidance

The concept of anticipatory guidance has been presented earlier in this article. Books for children can be used as anticipatory guidance for death education and the loss of a loved one. As anticipatory guidance with young children, it can be helpful for the book to present death as a natural part of all life, and not specifically in the human domain. Such books can help to relieve the fear and anxiety that may be expected to occur with a death experience. Many of the books in Table 2, although not under the heading of anticipatory guidance, could be used as anticipatory guidance if a death is expected or imminent.

6.2. Images of Heaven and the Afterlife

An important aspect of children’s literature dealing with death is the concept of the afterlife. In Malcom’s [18] qualitative research article, the researcher analyzed over 100 children’s storybooks touching on the spiritual afterlife. The findings of the study indicated that the portrayal of the spiritual world in the storybooks differs depending on who has died, and can help children cope with death related grief [18].

For instance, the researcher discovered that storybooks dealing with the death of a friend or a pet differed greatly in their portrayal of the afterlife from books dealing with the death of a parent or grandparent [18]. Children generally believe that friends and pets are dependent and need to rely on someone for continued care, as a result, “specific details about the afterlife are included in order to provide reassurance that pets and children are cared for and looked after in heaven” [18]. However, children often believe that their parents and grandparents are still strong and can take care of themselves in death as they did when they lived [18]. Deceased parents and grandparents are often depicted as watching over the child and guiding the child through life, while eagerly anticipating the day when the child and parent or grandparent are reunited in the afterlife [18].

Malcom’s research [18] concluded that the books reviewed were written with the intent of helping children deal with bereavement. These books helped to provide reassurance about the afterlife and helped to nourish the child’s emotional requirements during a time of possible confusion, stress, and anxiety [18].

6.3. The Grandparent Role

One aspect of children’s literature with death education is the role of the grandparent in these texts. Corr [15] explored the “ways in which grandparents are represented as sharing death and loss experiences in deathrelated literature designed to be read by or with children” [15]. The author examined 42 books dealing with grandparents and the topic of death.

Corr [15] included the names of the publications examined in the study and categorized the texts depending on the role that the grandparent played in the literature. These categories included: the death of a grandparent, grandparents who try to prepare a child for death, grief reactions after the death of a grandparent, funerals of grandparents, and memories of grandparents who have died [15]. Corr [15] concluded this literature helps to assist adults in interactions with children struggling with the death of a loved one.

6.4. Death of a Pet

The first loss that many children incur is the death of a pet. The loss of a beloved pet can be traumatic for anyone, but it can be especially traumatic for a child. Children often partake in the care of their pets and have a close bond with them. Whether the education is preparatory or during the grief process, it is important to be able to help the child understand the death and successfully grieve the loss. As previously mentioned, children generally believe that pets are dependent and need to rely on someone for continued care and the child may need to be reassured that the pet is cared for and looked after in the afterlife [18].

6.5. Activity Books and Death Education

Another literature resource for children dealing with the concept of death is activity books. These interactive books often have topical text as well as opportunities to draw, color, and relate stories and feelings. The use of

Table 2. Death: topical listing of children’s books.

activity books can aid the child in death education and the grieving process. Activity books often make the child feel comfortable in addressing death and grieving [19]. Carney provides a suggested list of activity books and websites for further resource information regarding death education for children at www.barklayandeve.com. Other activity books for children are provided at the Compassion Books website www.compassionbooks.com. When Someone Very Special Dies [20] is an activity book for children ages 6 - 12 years that deals with the topic of death and helps children through the grieving process.

7. MEDIA: MOVIES AND TELEVISION AND DEATH EDUCATION

Movies and television programs have various depictions of death. Violent death is a theme in many contemporary movies and television programs. The death of an older adult is also incorporated into this media. Nurses and adults need to be familiar with death as it is presented in this media and be prepared to answer children’s questions about death.

It is common for children to view Disney films and other movies. Many Disney films incorporate death and loss into their storylines. A study conducted by Cox, Garrett, and Graham [21] explored how these films depiction of death affected children’s understanding of death. The study discovered that some Disney films provide an ambiguous portrayal of death that may confuse children [21]. However, Disney and other family films may give adults a springboard for discussion about death since even a film with a confusing portrayal of death can be employed as a tool for discussing death with children [21]. It can be presumed that with careful screening for content, and appropriateness for developmental stage, these movies may be a valuable tool for death education.

8. SOME RESOURCES FOR DEATH EDUCATION

Table 2 listed books that can be used as resources. The Compassion Books (www.compassionbooks.com) and Barklay and Eve (www.barklayandeve.com) websites have numerous additional books available. Barklay and Eve were started by Karen Carney, a nurse and licensed clinical social worker, who has received the American Cancer Society’s Lane W. Adams Award for her work in the field of death education. For more than 20 years Compassion Books has compiled a listing of books on death and dying for children and professionals. Currently more than 400 books, videos, and audios, categorized by children’s age group, are available through their online or print catalog. Some of the many topics at the Compassion Books website include books on: losing a sibling, losing a parent, losing a grandparent, losing a pet, suicide, sudden or violent loss, and divorce. The information provided for professionals in relation to teaching death education can be especially helpful for nurses.

The Association for Death Education and Counseling (www.adec.org) has numerous resource links, publications, and resources. In the event of an impending death, organizations such as the American Hospice Foundation (www.americanhospice.org) and Hospice Foundation of America (www.hospicefoundation.org) can be helpful. Resources on grief for children and their families include organizations such as the National Alliance for Grieving Children (www.childrengrieve.org), Annie’s Hope (www.annieshope.org), the Highmark Caring Place (www.highmarkcaringplace.com), the Center for Loss and Bereavement (www.bereavementcenter.org) and Children’s Grief (www.childrensgrief.org). The Center for Hospice Care Southeast Connecticut (www.hospicesect.org) has some excellent resources including a publication: Ways Adults Can Help a Grieving Child [22]. The organization also has a Facebook page at www.facebook.com/hospicesect.

Individuals look for local resources by contacting funeral homes, crematories, churches, and hospice providers. Local places of worship often have resources to assist families with death, dying, and the bereavement process. Although internet resources are useful, their main aim is to point grieving families towards face to face counseling which is invaluable in grief related situations [23]. It is important for nurses to recognize the need for, and encourage the use of, professional counseling for the child and family.

9. CONCLUSION

Although death may be a challenging topic to approach with children, death is part of the natural lifecycle, and it is a common occurrence for children to have experience with death. It is crucial that nurses, parents, significant adults, and educators are capable of providing anticipatory guidance and death education to children, help the child cope with anticipatory grief, and facilitate anticipatory adaptation. Nurses should be prepared to provide support to children who have experienced death or where death is imminent or expected. Death is often a difficult topic for nurses and other adults to address with children. However, resources exist that can assist in this education. Unfortunately, many of these resources are “fugitive” in nature and not well known among those that should best be prepared to use them. This article has attempted to increase awareness of the resources available in relation to discussing death with children, preparing them for a death experience, and helping with the grieving process. A child experiencing death in the course of their life is inevitable, and being able to help the child understand death and be prepared for a death is an important role for nurses.

10. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Katherine Akers, MSN; Shannon Cobb, MSN; Lashondia Gibson, MSN; Charlotte MacDonald, MSN.

REFERENCES

- Kennedy, C., McIntyre, R., Worth, A. and Hogg, R. (2008) Supporting children and families facing the death of a parent: Part 2. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 14, 230-237.

- Mosby Inc. (2009) Mosby’s dictionary of medicine, nursing and health professions. 8th Edition, Mosby, St. Louis.

- Torbic, H. (2011) Children and grief: But what about the children? Home Health Care Nurse, 29, 67-77. doi:10.1097/NHH.0b013e31820861dd

- Jackson, M. and Colwell, J. (2001) Talking to children about death. Mortality, 6, 321-325. doi:10.1080/13576270120082970

- Bowie, L. (2000) Is there a place for death education in the primary curriculum? Pastoral Care, 18, 22-26.

- National Institute of Health Clinical Center (2012) Talking to children about death.

- Dunning, S. (2006) As a young child’s parent dies: Conceptualizing and constructing preventive interventions. Clinical Social Work Journal, 34, 499-514. doi:10.1007/s10615-006-0045-5

- Piaget, J. (1954) The child’s construction of reality. Basic Books, New York. doi:10.1037/11168-000

- Nagy, M. (1948) The child’s theories concerning death. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 73, 3-27.

- Vianello, R. and Marin, M.L. (1988) Children’s understanding of death. Early Child Development and Care, 46, 97-104. doi:10.1080/0300443890460109

- Zolotow, C. (1974) My grandson Lew. Harper Collins Publishers, New York.

- Center for Hospice Care Southeast Connecticut (2013) Ways children grieve according to age.

- Center for Hospice Care Southeast Connecticut (2013) Common Responses of children to the death of a loved one.

- National Association of School Psychologists (2012) Helping children cope with loss, death, and grief. Tips for teachers and parents.

- Corr, C. (2004) Grandparents in death-related literature for children. Journal of Death & Dying, 48, 383-397. doi:10.2190/UHT5-KYTM-ANWF-VBD5

- McGuire, S.L. (2003) Growing up and growing older: Books for young readers, Childhood Education, 79, 11- 12. doi:10.1080/00094056.2003.10522214

- Tompkins, G.E. (2001) Literacy for the 21st century: A balanced approach. Merrill Prentice Hall, Columbus.

- Malcom, N. (2010) Images of heaven and the spiritual afterlife: Qualitative analysis of children’s storybooks about death, dying, grief, and bereavement. Journal of Death & Dying, 62, 51-76. doi:10.2190/OM.62.1.c

- Carney, K. (2003) Barklay and Eve: The role of activity books for bereaved children. Journal of Death & Dying, 48, 307-319. doi:10.2190/5D4K-LWHX-3H17-7TDB

- Heegaard, M. (1988) When someone very special dies. Woodland Press, Minneapolis.

- Cox, M., Garret, E. and Graham, J. (2005) Death in Disney films: Implications for children’s understanding of death. Journal of Death & Dying, 50, 267-280. doi:10.2190/Q5VL-KLF7-060F-W69V

- Center for Hospice Care Southeast Connecticut (2013) Ways adults can help a grieving child.

- Auman, M. (2007) Bereavement support for children. Journal of School Nursing, 23, 34-39. doi:10.1177/10598405070230010601