Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.2 No.3(2012), Article ID:23127,4 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2012.23024

Healthy lifestyle for people with intellectual disabilities through a health intervention program

![]()

1Faculty of Health, Nutrition and Management, Oslo and Akershus University College, Oslo, Norway

2Department of Public Health Sciences, College of Applied Sciences Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden

Email: bente.lorentzen@gmail.com, britt-maj@home.se

Received 21 July 2012; revised 19 August 2012; accepted 27 August 2012

Keywords: Intellectual Disability; Nursing Care; Healthy Lifestyle; Physical Activities; Social Interaction

ABSTRACT

There are well known gaps related to health care service and public health interventions for people with Intellectual Disabilities (ID), but there is still lack of research information of what nurses can do to reducing health disparities of persons with ID. The present study aimed at exploring the views of people with ID about a healthy lifestyle, exercise, and to take part in a health promotion program. A qualitative method was an appropriate method for capturing the informants’ points of view. Participants were adults with intellectual disability who would be able to give their consent verbally and in written form. Women (n = 7) and men (n = 6). Data were collected from focus group interviews and analysed according to a qualitative content analysis of the tape-recorded and verbatim transcribed interviews. The participants took part in four workshops about healthy food, and ten physical activities addressing the connection to physical, social and emotional health. The results of the focus group interviews show that participants have knowledge about the importance of a healthy lifestyle for good health including physical activity and healthy food. Participants also describe social interaction and self-determination as important aspects in their life. It could then be concluded that the health promotion program result point at consciousness about a healthy lifestyle. There is still lack of research information of what public health nurses can do to reducing health disparities of persons with ID. Public health nurses work in community-based services and therefore they also might support persons with ID through health intervention programs.

1. INTRODUCTION

There are well known gaps related to health care service and public health interventions for people with Intellectual Disabilities (ID), as well as research information of what Public Health Nurses can do to reducing health disparities of persons with ID. Public Health Nurses work in community-based services and therefore they also may support persons with ID through health intervention programs. Public health for people with ID is an increasing area and it begins to be included in many national and community-based health plans in many countries. Today, we are more aware of the health needs of people with ID, but are we really aware of the support needed for this group, and that they are one of the most marginalised groups in Western society [1]. People with an ID have complex needs because of an increased variety of health care problems compared to the general population [2]. Care and support should be provided according to the needs of each individual in this group. Adults with ID should have the same variety of protective health services as those offered to the general population. This group needs on-going education regarding healthy living practices such as exercise, nutrition, oral hygiene and tobacco use [3]. Intellectual disabilities are significant limitations in intellectual functioning and conceptual, social and practical adaptive skills. Persons with ID are more likely to have physical disabilities, mental health problems, hearing impairments, vision impairments and communication disorders. In combination with limitations in intellectual functioning and adaptive behaviours, these coexisting disabilities make this group particularly vulnerable to health disparities.

1.1. Healthy Lifestyle

The WHO report [4] declares: “To ensure a healthy lifestyle, we recommend eating lots of fruits and vegetables, reducing fat, sugar and salt intake, and exercising.” It is also well known that adults with ID have a higher risk of obesity and the associated health risks with obesity, which are factors that could have an impact on their quality of life [5-7]. The prevalence of overweight, obesity and body fat percentage in older people with ID was measured through Body Mass Index and waist-to-hip ratio. When compared with the prevalence of the same factors in the general population overweight were highly prevalent in people with ID [8]. In group homes for adults with ID an education and nutrition structure with portion sizes menus was implemented. The result shows positive effects in changing unhealthy foods to healthy foods [9]. To explain the increased prevalence of obesity for some groups with ID, we find a variety of risk factors that include some level of ID, such as gender, age, social economic situation and genetic syndrome [10-12]. These factors seldom change, but a healthier lifestyle for people with ID can prevent obesity and improve their quality of life. Despite knowing about the increased risk for obesity, many studies have proven that people with ID often engage in little or no physical activity [12,13]. There are different reasons for explaining this lack of physical activity. Some people with ID do not have any activity choices in their daily life because of poor accessibility to leisure and exercise facilities. In a group of young females and males with mild Downs syndrome positive outcome was found regarding exercises with rehabilitation balls. The balance test revealed that the level of static one-legged balance was improved compared to a control group [14]. Running exercise for intellectually disabled individuals improved physical energy, selfconfidence as well as positive mood [15]. Fitness in adult athletes with ID was measured after sport specialisation exercises. The result showed that physical activity improved fitness and decreased health risks [16]. People with ID also need support in relation to transport and staffing constraints. Many communities have a lack of a clear policy and public health plans that include people with ID [17,18]. Healthy lifestyle interventions for people with ID are very scarce [6], which point at more research in this area [19].

According to the WHO report [3] a number of terms are used for ID with varying levels of acceptability across disciplines and professions. In the present study, the term suggested by the International Association for the Scientific Study of Intellectual Disabilities (IASSID) was chosen.

1.2. Purpose of the Study

The health promotion intervention program is part of a Public Health Program with the intention to help people with ID to choose a healthy lifestyle. The aim of the present study was to capturing the informants’ points of view, beliefs and perceptions of a healthy life style and expectations of the health promotion intervention program.

2. METHOD

2.1. Design

To take into consideration the aim of the present study, the focus was on qualitative methods. We found that focus group interviews were an appropriate method commonly used as a research method for conducting research with people with ID [20-22]. The health promotion intervention program is part of the Public Health Program in a midto large-sized municipality in Norway. The primary focus of the program is to help people with ID to choose a healthy lifestyle, with an aim to motivate and engage them in activities, nutrition and health. The intervention program in the present study was offered to all people with ID who live in the municipality, and lasted for one year. The activities presented below were tailored for persons with ID. The participants took part in workshops that took an integrated approach to health, addressing connections to physical, social and emotional health, and achieving improved health through healthy food and meaningful activities:

2.2. Intervention Program

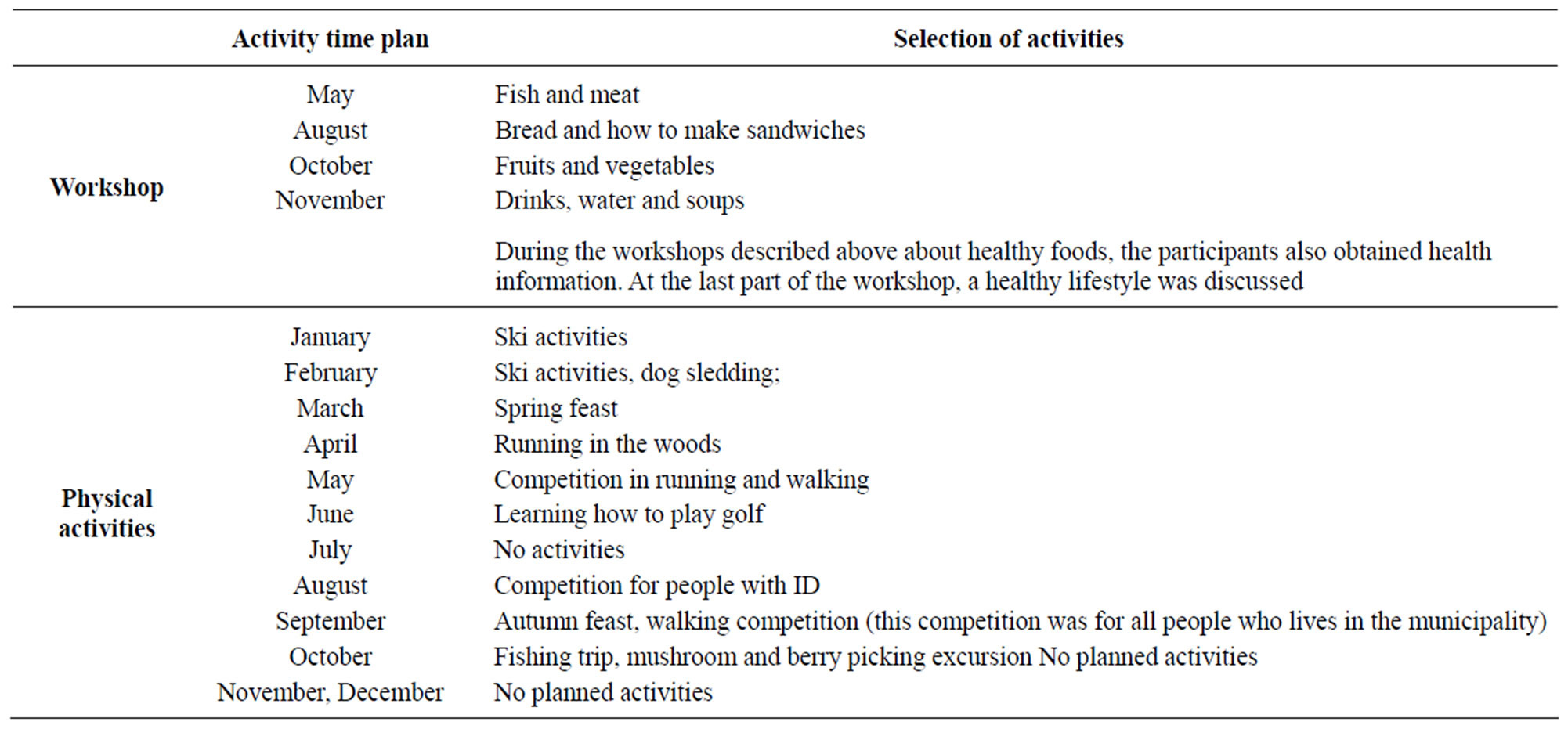

The intervention program in the present study was offered to all people with ID who live in the municipality, and lasted for one year. The activities presented in Table 1 were tailored for persons with ID. The participants took part in workshops that took an integrated approach to health, addressing connections to physical, social and emotional health, and achieving improved health through healthy food and meaningful activities.

2.3. Sample

After the local management agreed that their unit could participate in the study, the researchers asked them to choose those who would give their consent (both verbally and in written form) to participating in the study. The criteria for inclusion were that the participants were capable of cooperation with the necessary procedure, and could be regarded as understanding the meaning of participating in small focus group interviews. The sample for the study was adults with ID in the public health intervention program. The health program leader in the municipality recommended a work centre for persons with ID for the study, and there were two centres to choose from. Before the researchers conducted the interviews, they had a conversation with the public health leader and the working leader in order to ensure that the questions to be used in the focus group interviews were appropriate. Informal meetings were carried out with health professionals to get their point of view of the results of the program. The health centre had persons (n = 25) who all had taken part in the healthy lifestyle program.

Table 1. The activities have connections to physical, social and emotional health through healthy food and meaningful activities.

The researchers asked all the persons chosen by the work leader whether they wanted to take part in the focus group interviews. The participants who decided to take part were women (n = 7) and men (n = 6) between the ages of 18 and 35.

2.4. Measures

The focus group interviews were used to exploring the participants’ views about a healthy lifestyle and its connection to physical health as well as perceptions and expectations of the Public Health program. A semi-structured interview guide was used based on three main areas: food, physical activities and social activities. The sessions were audio taped and transcribed verbatim. Pictures from the activities in the intervention program were used to help the participants remember various activities they had participated in.

Focus groups are commonly used as a research method for conducting research with people with ID [20-22]. This is because the focus groups include a large amount of the participants’ opinions, suggestions and ideas, and do not require written language skills. In the present study, the intention was to capture the lived experiences of the participants. During the interviews, the informants were asked to freely describe their perceptions and thoughts in relation to the healthy lifestyle activity program as well as which activities they liked, preferred, disliked. The interviewer offered participants to turn off the tape recorder and take notes instead, but they insisted on tape recording because they regarded the interview as being important and wanted their words to be heard in their exact form. When interviewing people with intellectual disabilities it is important to be flexible and adapt to each individual’s circumstances [23]. In the present study that means that each participant decided on the time and place as well as in which of the focus groups they would participate in, as it was important that each participant feel at ease. It is also important to consider verbal signals to ensure that the person is still happy to continue with the interview. Therefore two persons were present at each interview to take notice of verbal and body language. The meeting room was quiet, comfortable and free from outside distractions. Participants were assembled around a table so they could see each other. Each interview lasted for approximately 1 - 1.5 hours. The focus group leader had good communication skills and directed the discussion without being part of it. Her aim was to create a relaxed, informal atmosphere in which the participants felt free to express their opinions, though she did not express her own opinions or make judgments on the opinions of the participants. The focus group leader asked a series of open-ended questions ranging from general to specific, and the participants expressed their opinions, experiences and suggestions. The focus group leader allowed the discussion to go in new directions as long as the topics were relevant to the subject of the interview. All members of the group were encouraged to participate, but one person was not allowed to dominate the discussion.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The purpose and procedure of the focus group interviews were carefully explained to the participants, who were assured of confidentiality. An ethical issue that could arise from the participants was that they were in a state of dependence in relation to the project leader in charge of the Public Health Program, particularly with concern to a question in which the participants were requested to describe the meaning of the intervention program. The rules of the Norwegian Social Science Data Services (NSD) at the University of Bergen were followed regarding the participants receiving the usual assurance about anonymity, confidentiality and the right to withdraw at any point without prejudice. Comments are directly quoted, while always ensuring that the speaker is not identified. From an ethical perspective, the qualities as judged by the Declaration of Helsinki [24] are that the research design and the need in society for such a project are deemed to be of importance.

2.6. Analytic Strategy

The starting point for the analysis is qualitative, which means that the researcher is open to the text and does not make use of any theory or preconceived ideas in order to understand the text [25]. In this study, the term theory means any explicitly defined hypothetical construction. A qualitative analysis of the interviews was performed in several steps using the analytical technique [26-28]. A close examination of the data was conducted and compared for both similarities and differences. The first step was a content analysis of the tape-recorded and verbatim transcription of the interviews. Each of the written accounts was read several times in order to grasp the content. Secondly, each account was studied to qualitatively identify different comments which together comprise the total account. Each comment was considered as a unit of analysis and defined as an utterance that provided new information about the participants’ impressions and opinions [29]. Questions were asked about the phenomena as reflected in the data and reviewed for emerging themes, and were categorized, coded and counted. The open coding of each interview classified the data and allowed for the identification of categories. Even so, the researcher’s cultural and linguistic understanding of the phenomenon was the prerequisite for coming to an understanding of the participants’ accounts.

The result of the present study will be exemplified by using excerpts from the respondents and from the previous research in the area. In addition some excepts will be presented that might point at empowerment. Empowerment is a complex experience of personal change, with a key principle being self-determination [30]. There are two dimensions to the process of empowerment, inter-personal and intra-personal, meaning either from the point of view of the provider and patient interaction, the patient alone or both [31].

3. RESULTS

Main Categories

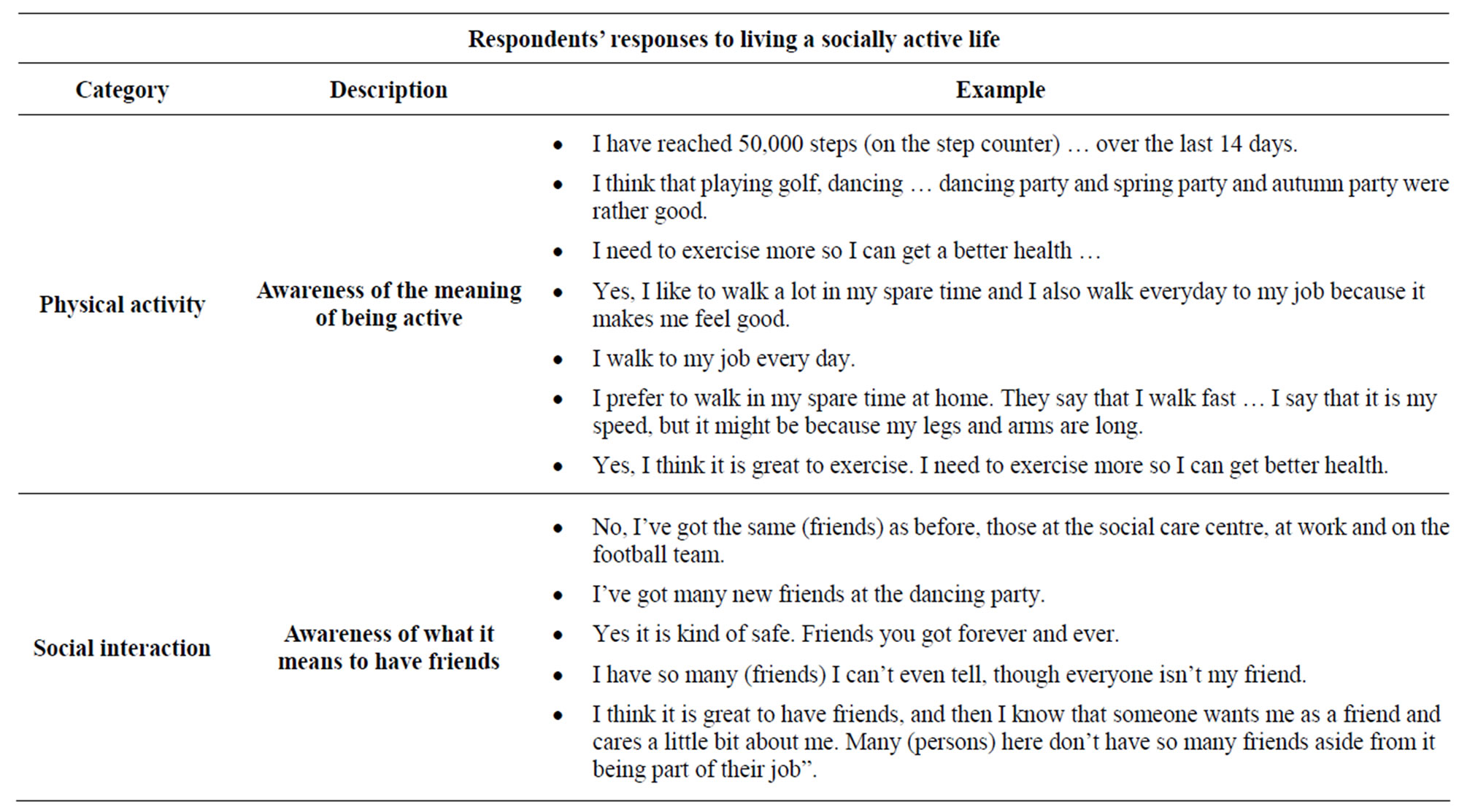

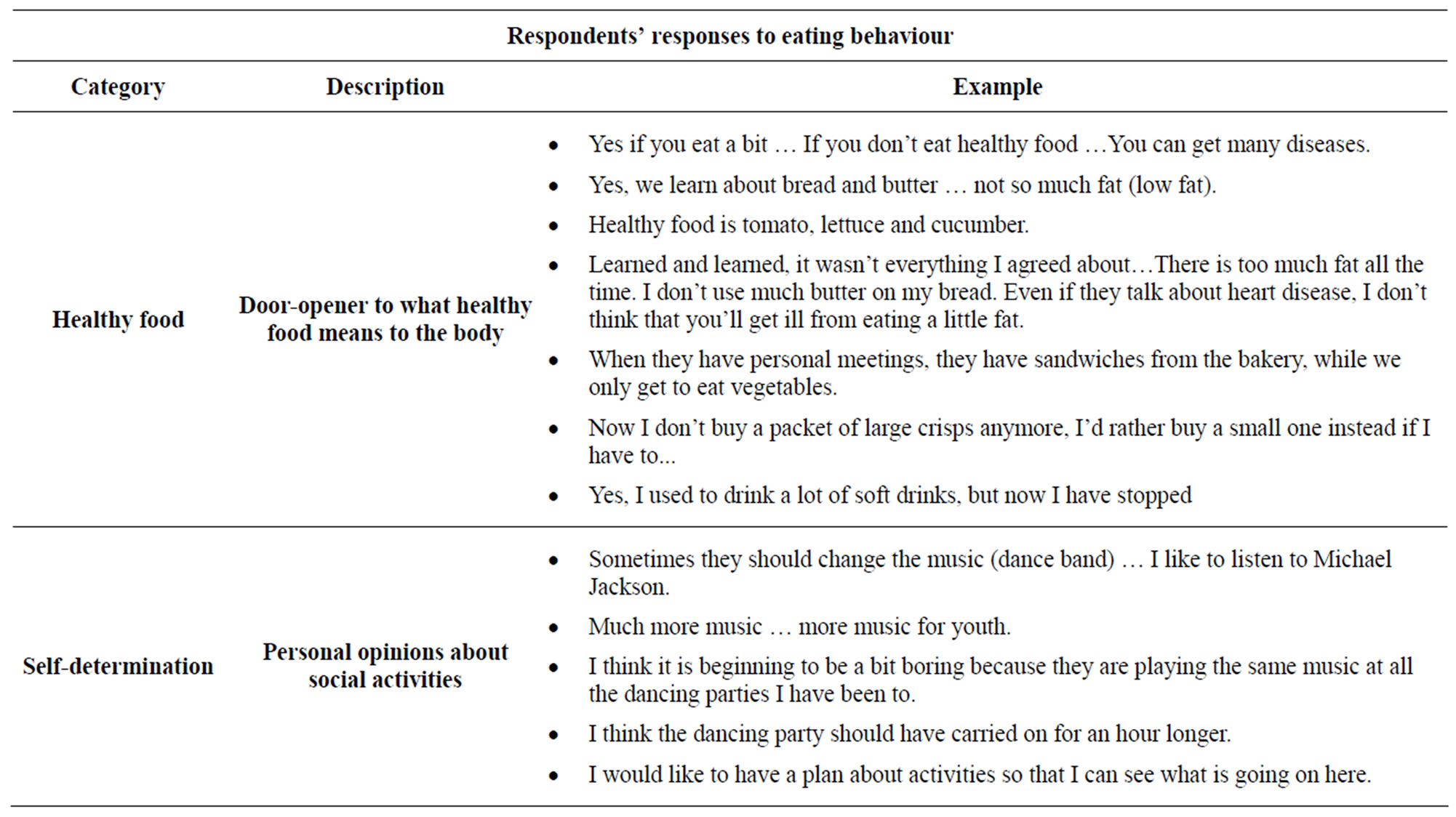

The main results of the present study were that the participants show awareness of characteristics of a healthy lifestyle. They became aware of the importance of being physically and socially active as well as healthy eating behaviour. The four main categories are physical activities, social interaction, healthy food and self-determination.

4. DISCUSSION

This study describes a health promotion intervention program for people with intellectual disabilities. The health promotion program is aimed at helping people with ID to choose a healthy lifestyle. The intention of the study has been to exploring the views of people with ID about health and exercise and to take part in a health promotion intervention program. It was important to acquire information about the participants’ points of view of a healthy lifestyle, because people with ID have complex needs as a result of an increased variety of health care problems compared with the general population [2]. Hypertension, hyperglycaemia and hyperlipidemia prevalence of adolescents with intellectual disabilities were common in this group compared to the general population [32].

The main results of the present study were that the participants show awareness of characteristics of a healthy lifestyle. In addition, they expressed that social interaction was an important part of their life. Since only views about health and lifestyle after the health promotion program was collected, the result must be interpreted with cautiousness. Eating pattern and social activities though could be a result of the health promotion program. In addition participants became aware of the importance of being physically active for a healthy life style, a result in line with previous research [33,34].

A change towards a healthier eating behaviour was found in several excerpts such as: “… Now I don’t buy a packet of large crisps anymore, I’d rather buy a small one instead if I have to …”, and “Yes, I used to drink a lot of soft drinks, but now I have stopped.” This result is in accordance with research that suggests that one means of encouraging people with intellectual disabilities to lead a healthier life is that health practitioners work directly with individuals or small groups [35]. Clinical improvement in nutritional deficit was found in adults with ID when a planned menu was followed. The intervention program aimed at improving food planning by introducing whole grains, vegetables and low-fat proteins [36]. There is also an agreement about the need for a variety of health promoting program designed for persons with ID [37].

Participants express awareness of the importance of being physically active for a healthy life style. An except that points in this direction is; Yes, I like to walk a lot in my spare time and I also walk everyday to my job because it makes me feel good. This excerpt is in line with previous research [33]. Slow walking has proven useful for persons with ID. Previous research shows that energy expenditure of adults with and without ID during common activities of daily living is different between the two groups. Slow walking as a moderate-intensity physical activity offers significant health promotion opportunities for adults with ID [34].

Social interaction was important for the participants. They express that activities such as dancing were important because it was a way to bring people together and a way to find new friends. It could be exemplifies with excerpts such as: “... I have made many new friends at the dancing party”. In line with this result is a study supporting the result in the present study; “in order to generate friendships between people with more severe learning disabilities, the physical opportunity to meet others in a supportive environment is much more important than the severity of their learning disabilities and how socially skilled they are.” [38, p. 209] Research show that sport is also important, not only for physical and emotional health, but to build social connections [39]. In a WHO report [3] it was pointed out that people with intellectual disabilities may have restricted social roles and more limited social networks than people without disabilities, and thus may have fewer opportunities to benefit from many common experiences open to those without disabilities [3]. People with ID undertake less physical activity than the general population, and may rely on others to help them to access activities [18]. Adapting public health nurses practice to include strategies to help individuals to be active is possible but not without challenge. Levine [40] argues that family caregivers’ willingness to help does not remove the responsibility from health professionals and community organisations.

When responding to the question: What is a good life for you? Implicitly, some excerpts point towards having a vision in life. One example is; “I think it is great to have friends, and then I know that someone wants me as a friend and cares a little bit about me ...”

Some of the respondents’ excerpts point at elements of the empowerment process [30,31]. However, it is important to be cautious about this connection. Excerpts though that might point at empowerment are; becoming responsible for your life, could be exemplified by “… yes if you eat a bit … If you don’t eat healthy food … You can get many diseases”. Establish goals and healing yourself, are important aspects in the empowerment process and could be exemplified by the excerpts such as; “I need to exercise more so I can get achieve better health”, Yes, I like to walk a lot in my spare time and I also walk everyday to my job because it makes me feel good.” A key principle in empowerment is self-determination. This is exemplified by: “I think the dancing party should have carried on an hour longer”. One could argue that there are disadvantages to adopting the thinking of empowerment. The respondent who is unable or unwilling to be responsible for his or her own life may prefer a more prescriptive approach and find it difficult to respond in a positive manner. Therefore, the person may transfer the power back to the assistant. However, by transferring the responsibility for a healthy lifestyle to the person they are working with, the assistant can expend less energy in motivating the person and perhaps feel less guilt about asking that person to follow a healthy lifestyle that they themselves might not be able to follow. However, as pointed out earlier in the discussion, carefulness of the connection to empowerment interpretation is important.

Weaknesses and Strength in the Method

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, focus group interviews were used because existing objective test instruments do not yield a representative picture of the subjective perception of the quality of life in this group. However, limitations of the interviews could appear for various reasons. For instance, in the beginning of the interviews it was obvious that the respondents found it difficult to connect with what they do in their daily life. However, when the focus group interviewer showed photos from activities in the intervention program, the respondents found connections to their daily life, particularly in relation to food and social activities. I addition a weakness could be that objective data was not collected. However, the main focus of the study has been to explore the views of participants with ID about a healthy lifestyle. A further weakness could be the questions put forward to the participants in terms of whether these have been understood by the respondents. A pre-test though was used to ascertain that respondents understood the questions to be used during the focus group interviews. Regardless of this procedure, this weakness cannot be ruled out. Strength of the current method was the use of photos from different activities conducted during the health promotion intervention program.

5. CONCLUSION

The healthy lifestyle program described in the present study offers a promising approach to promoting health among people with ID. Indications of awareness about health behaviour and health related attitudes were found. Nevertheless, there are aspects of the program that could be further developed, e.g. individualized activities as a motivating factor. In addition, there is still lack of research information of what public health nurses can do to reducing health disparities of persons with ID. Therefore, increasing nurses’ sense of control over their ability to support individuals with ID to achieve a healthy lifestyle will be most important.

REFERENCES

- Hall, E. (2005) The entangled geographies of social exclusion/inclusion for people with learning disabilities. Health and Place, 11, 107-115. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.10.007

- Jones, R.G. and Kerr, M.P. (1997) A randomized control trial of an opportunistic health screening tool in primary care for people with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 41, 409-415. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.1997.tb00728.x

- World Health Organization (2000) Ageing and intellectual disabilities—Improving longevity and promoting healthy ageing: Summative report. World Health Organization, Geneva.

- World Health Organization (2010) Nutrition a Healthy Lifestyle. http://www.euro.who.int/en/what-we-do/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/a-healthy-lifestyle.

- Bradley, S. and Tackling, S. (2005) Obesity in people with learning disability. Journal of Learning Disability Practice, 8, 7.

- Hamilton, S., Hankey, C.R., Miller, S., Boyle, S. and Melville, C.A. (2007) A review of weight loss intervenetions for adults with intellectual disabilities. Obesity Reviews, 8, 339-345. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00307.x

- Melville, C.A., Hamilton, S. Hankey, C.R., Miller, S. and Boyle, S. (2007) The prevalence and determinants of obesity in adults with intellectual disabilities. Obesity Reviews, 8, 223-230. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00296.x

- De Winter, C.F., Bastiaanse, L.P, Hilgenkamp, T.I.M., Evenhuis, H.M. and Echteld, M.A. (2012) Overweight and obesity in older people with intellectual disability. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 33, 398-405. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2011.09.022

- Humphries, K., Pepper, A., Traci, M.A., Olson, J. and Seekins, T. (2009) Nutritional intervention improves menu adequacy in group homes for adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities, Disability and Health Journal, 2, 136-144. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2009.01.004

- Bhaumik, S., Watson, J.M., Torp, C.F., Tyrer, F. and McGrother, C.W. (2007) Body mass index in adults with intellectual disabilities: Distribution, associations and service implications: A population-based prevalence study. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 52, 287-289. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2007.01018.x

- Emerson, E. and Hatton, C. (2007) Socioeconomic disadvantage, social participation and networks and the self-rated health of English men and women with mild and moderate intellectual disabilities: Cross sectional survey. European Journal of Public Health, 18, 31-37. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckm041

- Robertson, J., Emerson, E., Gregory, N., Hatton, C., Turner, S., Kessissoglou, S. and Hallam, A. (2000) Lifestyle related risk factors for poor health in residential settings for people with intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 21, 469-486. doi:10.1016/S0891-4222(00)00053-6

- McGuire, B.E., Daly, P. and Smyth, F. (2007) Lifestyle and health behaviors of adults with an intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 51, 497- 510. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00915.x

- Jankowicz-Szymanska, A., Mikolajczyk, E. and Wojtanowski, W. (2012) The effect of physical training on static balance in young people with intellectual disability. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 33, 675-681. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2011.11.015

- Vogt, T., Schneider, S., Abeln, V., Anneken, V. and Strüder, H.K. (2012) Exercise, mood and cognitive performance in intellectual disability—A neurophysiological approach, Behavioural Brain Research, 226, 473-480. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2011.10.015

- Guidetti, L., Franciosi, E., Gallotta, M.C., Emerenziani, G.P. and Baldari, C. (2010) Could sport specialization influence fitness and health of adults with mental retardation? Research in Developmental Disabilities, 31, 1070- 1075. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2010.04.002

- Bodde, A.E. and Seo, D.-C. (2009) A review of social and environmental barriers to physical activity for adults with intellectual disabilities. Disability and Health Journal, 2, 57-66. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2008.11.004

- Peterson, J.J., Janz, K.F. and Lowe, J.B. (2008) Physical activity among adults with intellectual disabilities living in community setting. Preventing Medicine, 47, 101-106. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.01.007

- Wilhite, B. and Shank, J. (2009) In praise of sport: Promoting sport participation as a mechanism of health among persons with a disability. Disability and Health Journal, 2, 116-127. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2009.01.002

- Fraser, M. and Fraser, A. (2001) Are people with learning disabilities able to contribute to focus groups on health promotion? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 33, 225-233. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01657.x

- Nind, M. (2008) Conducting qualitative research with people with learning, communication and other disabilities: Methodological challenges. University of Southampton, Southampton.

- Perry, J. and. Felce, D. (2004) Initial findings on the involvement of people with an intellectual disability in interviewing their peers about quality of life. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 29, 164-171. doi:10.1080/13668250410001709502

- Baxter, V. (2005) Learning to interview people with learning disabilities. Research Policy and Planning, 23, 175-180.

- Herméren, G. (1986) The cost of knowledge. Ethical problems and principles of research in the humanities and social sciences. Humanistisk-samhällsvetenskapliga Forskningsrådet, Stockholm.

- Karlsson, G. (1993) Psychological qualitative research from a phenomenological perspective. Almquist & Wiksell International, Stockholm.

- Crabtree, B.F. and Miller, W.L. (1992) Doing qualitative research. Sage Publications Ltd., Newbury Park.

- Patton, M.Q. (1990) Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Sage Publications Ltd., Newbury Park.

- Miles, M.B and Huberman, A.M. (1994) Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage Publications Ltd., Thousand Oaks.

- Morse, J.M. and Field, P.A. (1996) Nursing research: The application of qualitative approaches. 2nd Edition, Chapman& Hill, London.

- White, T.A. (1989) Empowering yourself, empowers patients. In course syllabus: New approaches to patient care in diabetes. University of Michigan, Michigan.

- Aujoulat, I., D’Hoore, W. and Deccache, A. (2007) Patient empowerment in theory and practice: Polysemy or cacophony? Patient Education and Counseling, 66, 13-20. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2006.09.008

- Lin, P.-Y., Lin, L.-P. and Lin, J.-D. (2010) Hypertension, hyperglycemia, and hyperlipemia among adolescents with intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 31, 545-550. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2009.12.002

- Abdullah, N., Horner-Johnson, W., Drum, C.E., Krahn, G.L., Staples, E., Weisser, J. and Hammond, L. (2004) Healthy lifestyle for people with disabilities. Californian Journal of Health Promotion, 2, 42-54.

- Lante, K., Reece, J. and Walkley, J. (2010) Energy expended by adults with and without intellectual disabilities during activities of daily living. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 31, 1380-1389. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2010.06.022

- Chadwick, D.D., Craven, M. and Chapman, M. (2005) Fighting fit? An evaluation of health practitioner input to improve healthy living and reduce obesity for adults with learning disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 9, 131-144. doi:10.1177/1744629505053926

- Humphries, K., Pepper, A., Traci, M.A., Olson, J. and Seekens, T. (2009) Nutritional intervention improves menu adequacy in group homes for adults with intellectual or developmental disorders. Disability and Health Journal, 2, 136-144. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2009.01.004

- Thorn, S.H., Pittman, A., Myers, R.E. and Slaughter, C. (2009) Increasing community integration and inclusion for people with intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30, 891-901. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2009.01.001

- Whithouse, R. and Chamberlain, A. (2001) Obrien, increasing social interactions for people with more severe learning disabilities who have difficult developing personal relationships. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 5, 209-220.

- Wilhite, B. and Shank, J. (2009) In praise of sport: Promoting sport participation as a mechanism of health among persons with a disability. Disability and Health Journal, 2, 116-127. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2009.01.002

- Levine, C. (2008) Family care giving. In: Crowley, M. Ed., From Birth to Death and Bench to Clinic: The Hastings Center Bioethics Briefing Book for Journalists, Policymakers, and Campaigns, The Hastings Center, New York, 63-68.