Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Vol.3 No.7(2013), Article ID:35805,6 pages DOI:10.4236/ojog.2013.37093

Evaluation of process management of postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony*

![]()

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Division of Feto-Maternal Medicine and Obstetrics, Medical University Vienna, Vienna, Austria

Email: #rainer.lehner@meduniwien.ac.at

Copyright © 2013 Iris Holzer, Rainer Lehner This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 18 June 2013; revised 20 July 2013; accepted 29 July 2013

Keywords: Postpartum Hemorrhage; Uterine Atony; Management Process

ABSTRACT

Objective: To evaluate the management process and the guidelines for management of postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony at the General Hospital Vienna, Medical University Vienna. Material and Methods: A retrospective analysis was carried out on all 24 cases of postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony with an estimated blood loss of more than 800 mL, in which standardized guidelines were obtained. We included all women who gave birth at the General Hospital of Vienna, the Medical University Vienna, during the period from January 1st 2003 and December 31st 2009 and who suffered blood loss 800 mL at minimum due to uterine atony. Results: The guidelines were in use for 14% - 71%. The average blood loss of the 24 cases with uterine atony was 1342 mL. Conclusion: The management process of postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony deviates from the hospital’s guidelines in many cases.

1. INTRODUCTION

Postpartum hemorrhage is the leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. From that uterine atony is seen as the most frequent etiology [1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, primary postpartum hemorrhage is defined as blood loss more than 500 mL in the first 24 hours postpartum [2].

If clinical signs of uterine atony emerge and all other causes of postpartum hemorrhage can be excluded, medical treatment has to be started immediately. Every woman with massive postpartum hemorrhage should receive red blood cell transfusions in time to prevent the consequence of cardiovascular shock or disseminated intravascular coagulation [3]. Postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony is treated initially by bimanual uterine compression, followed by oxytocin, prostaglandins and ergot alkaloids [4].

If medical treatment fails and there is still persistent bleeding, a tamponade of the uterus or the external aortic compression [5] may be effective in decreasing hemorrhage and subsequent potential morbidity and mortality. Surgical interventions such as uterine artery ligations, compressive uterine sutures as the B-Lynch surgical technique or an arterial embolization in patients with stable vital signs should be used to obviate the need for hysterectomy. Because of these uterus preserving techniques, the indication for hysterectomy in cause of excessive postpartum hemorrhage is very rare. At the General Hospital of Vienna it is published as 1.39/1000. This figure also includes other causes like an abnormally adherent placenta or uterine rupture. But it is still the last resort in all cases of persistent hemorrhage after conservative and uterus preserving surgical therapy [6].

Recently published data indicate that recombinant activated factor VII might prevent emergency hysterectomy and reduce bleeding. It should be considered in the management of massive postpartum hemorrhage unresponsive to conventional therapy as a last try to avoid hysterectomy [7].

The aim of the study was to present the management process of postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony from a tertiary referral hospital in Central Europe and evaluate the associated hospital’s guidelines.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

A retrospective analysis was carried out on all cases of postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony with an estimated total intraand postpartum blood loss of 800 mL and more identified during the period from 1st January 2003 and 31st December 2009 at the General Hospital of Vienna, the Medical University Vienna. According to the publication of Sheikh et al. a new definition of massive postpartum hemorrhage has been introduced, being not only the blood loss of more than 1000 mL, but furthermore the peripartum fall in hemoglobin concentration of more than 4 g/dl or acute blood transfusion of four or more units of blood [8]. Our prime intention was to focus on massive postpartum hemorrhage, but as it is difficult to estimate or measure blood loss exactly and blood loss tends to be underestimated, we decided to include cases with an estimated blood loss of 800 mL as well. For inclusion in our analyses the cases had to be classified as uterine atony in the medical records. Except a low amount of blood loss there were no exclusion criteria.

Twenty-four cases were identified and then analysed. Data were obtained by the clinical documentation system of the maternity clinic, PIA® database, and the general documentation system KIS (hospital information system). The relevant data were found by means of the PIA® database and patient charts, surgery reports, records of the anesthesiologists, records of the midwives and hospital discharge summaries from the general documentation system KIS.

The aim of the analysis was to evaluate how the management process of massive postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony adheres to the hospital guidelines. The guidelines for management of postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony at our clinic were established by the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Medical University Vienna, referring to the OEGGG, the Austrian Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Application of recombinant activated factor VII as an optional item in consultation with the anesthesiologists was added in 2007. As this item is considered as an optional item the addition was not accounted for in our analyses.

Guidelines for management of postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony at the Medical University Vienna, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Division of Feto-maternal Medicine and Obstetrics:

1) Establish intravenous access using large bore cannula and inform senior obstetricians and senior anesthesiologists 2) Check for other causes of bleeding (genital tract trauma, retained placental tissues, coagulopathy), compress the uterus and give 10 IU oxytocin as an iv bolus. Set up a continuous infusion with 40 IU oxytocin in 500 mL (125 mL/h). Administer methylergometrine 0.2 - 0.5 mg im or iv. The use of carbetocin as treatment of a present atonic postpartum hemorrhage has not been evaluated in studies, but in this emergency situation it is recommended by this guideline (1 ampule with 10 mL saline as an iv bolus). The use of 10 IU oxytocin intravenously as a bolus is known to be associated with hypotension, myocardial changes, decreased cerebral perfusion and tachycardia, but it is recommended in this life-threatening situation.

3) Give prostaglandin F2α intravenously: 30 - 100 µg/ min. (1 ampule a’5 mg with 1000 mL saline).

4) Prepare blood transfusion, which has to be ordered from Department of Blood Transfusion, blood bank and give it without performing cross match.

5) Correction of blood loss, volume substitution and substitution of coagulation factors. Intensive care monitoring should be obligatory.

Further measueres (optional):

Direct intramyometrial injection of prostaglandin F2α up to 5 mg (dilute 1 ampule with 20 mL saline).

Insert a uterine packing tamponade using prostaglandin-soaked gauze (10 mg prostaglandin 2Fα with 100 mL saline) or insert an intrauterine infusion with a catheter (3 - 4 mL/ min for 10 min, afterwards 1 mL/min for 12 - 24 hrs). Concentration: 20 mg prostaglandin F2α diluted with 500 mL saline.

The life-threatening situation of massive postpartum hemorrhage can over weigh the contraindications. If vital signs are stable, uterine packing tamponade or uterus preserving surgical therapy is recommended.

Surgical therapy such as laparotomy, uterine artery ligations, B-Lynch compressive uterine sutures or hysterectomy should be done according to the standard guidelines.

The application of recombinant activated factor VII should be considered as additional therapy and in consultation with the anesthesiologists, as an option in off label use.

All items of the guidelines are mandatory as long as the bleeding persists. Item a) through f) are the most important items and the items that are easiest to perform. In case of persistent blood loss, further measures are required. These measures should by chosen with regard to the vital signs of the patient and the expertise of the attending team. If the bleeding stops, no more items of the guidelines need to be performed.

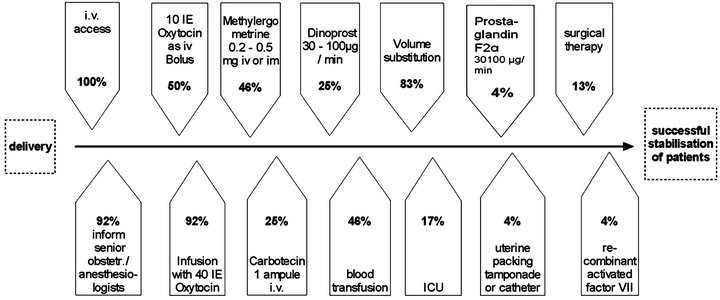

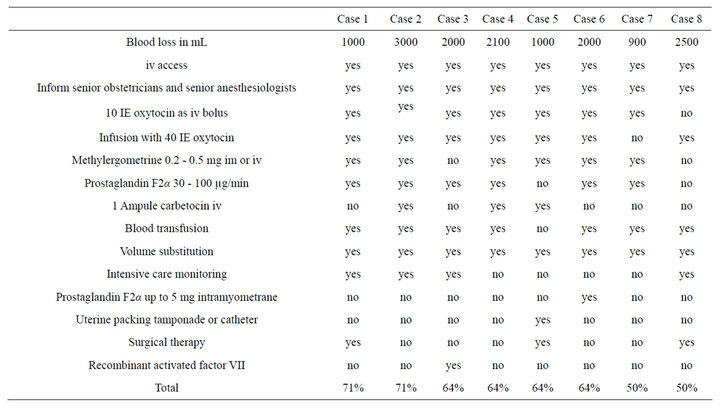

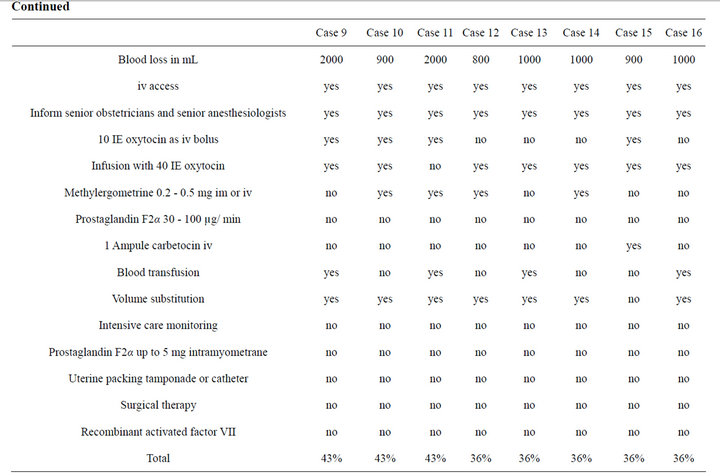

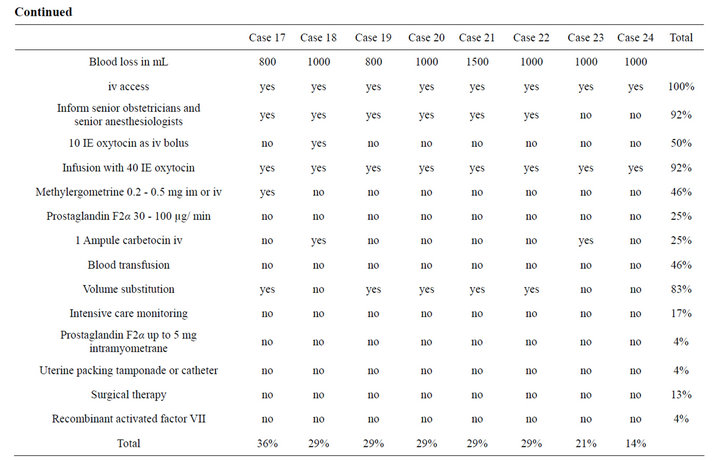

It was precisely analysed for each case which and how many items of the guidelines were undertaken and which and how many items of the guidelines were omitted. For this purpose the guidelines were divided into 14 main steps. We set up a table with all 24 patients in the horizontal line and the 14 steps of the guidelines in the vertical line. For each patient and each item of the guideline, there was a “yes”, if the item had been undertaken or a “no”, if the item had been omitted. Furthermore, we calculated the percentage rate of each step of the guideline, how often it had been performed. For each patient, the percentage rate was calculated, how many steps had been implemented in sum. We classified a step as “yes”, if it had been documented in any of the hospital documentation systems. If there was no documentation, we classified a step as “no”. Furthermore, we created a time line with all steps of the guideline in the correct order from point of delivery to the successful stabilization of the patients. We calculated the cumulative percentage rate how often they had been performed. SmartDraw was used for creating the timeline in Figure 1.

The study was approved by the ethics commission of the Medical University of Vienna and the General Hospital Vienna on January 29, 2010 (Number 1191/2009).

3. RESULTS

Table 1 shows every step of the guideline and the percentage, how often it had been implemented and it shows every case and the percentage, how many steps of the guidelines were operated in each case in sum in descended order of frequency. For each case we stated the total intraand postpartum amount of blood loss. The average blood loss of all 24 cases with postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony was 1340 mL.

Figure 1. Time line of all therapeutic interventions.

Table 1. All cases of postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony and their management process.

In our analyses we defined outcome as the point of the management process when bleeding stops. If bleeding has stopped, no more items of the guidelines need to be performed. In Table 1 we listed the percentage how many items had been performed and the blood loss of each case. To correlate clinical adherence with outcome, logistic regression analyses need to be performed. However, the small number of series would not reach statistical power.

In the time line in Figure 1 all therapeutic interventions from point of delivery to the successful stabilisation of the patients are listed. It shows the ideal order of the management process and the percentage rate how often they actually had been performed.

4. DISCUSSION

Documentation turned out to be a limitation of our retrospective analysis. Heterogeneity in quality and form of documentation and inconsistency of documentation in some cases were obvious. Relevant data should have been recorded in the PIA® database, the official documentation system of the maternity clinic. In several cases retrospectively we were not able to find it in this database and had to search patient charts, surgery reports, records of the anesthesiologists, records of the midwives and hospital discharge summaries as well. The apparent inconsistency of documentation may be explained by the life-threatening situation of massive postpartum hemorrhage. Due to the enormous stress of dealing with this life-threatening situation, the consequence seemed to be that documentation of the management process was disregarded by all participants. Thus, as the medical records may not be entirely complete or accurate, it may be hypothesized that in a few cases more therapeutic interventions had been implemented than documented, but it may almost be excluded that it is vice versa. Lain et al. published in their validation study about documentation of obstetric hemorrhage in hospital discharge data in Australia that diagnosis and procedure codes of obstetric hemorrhage tended to be under-reported and they indicated that the data sets should be improved with more complete documentation in medical records [9]. Complete and accurate documentation is not only important for the actual success of the treatment of the patients, but also for the purpose of research and evaluation and for forensic reasons. In case of severe complications that occur at therapeutic interventions that are not documented in any of the hospital’s documentation systems, it would draw serious legal consequences with an adverse situation for all obstetricians and anesthesiologists involved. In order not to emphasize the negative examples, we want to mention that we found many complete and accurately reported cases as well.

In the acute situation of postpartum hemorrhage with an increasing blood loss that can turn into a life-threatening event, indication for blood transfusion is more liberal as usual. The indication is assessed clinically by means of vital signs and shock index. Afterwards the complete blood count including hematocrit is done retrospectively and therefore it is not the main criteria for blood transfusion. Blood transfusion without cross matching is warrantable and recommended in this emergency situation.

According to the study of Roethlisberger et al. about early postpartum hysterectomy at our hospital, presentations of surgical treatments for uterine atony were being performed at our center to increase the use of these methods [6]. In spite of these presentations of surgical treatment, specific guidelines, staff education and the guidelines in form of quick reference cards the management process of postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony deviates in many cases from the hospital’s guidelines. A strategy to enhance the management process of massive postpartum hemorrhage and to decrease the incidence of severe cases is the use of check lists with the steps of the guidelines. It is recommended to place the check list at every delivery room and operating room in an easily accessible way, not only to have the guidelines close at hand in case of severe postpartum hemorrhage, but also to improve quality of documentation. In order to avoid legal consequences in case of any treatment processes with negative outcome or in case of any complications, checking off every implemented step of the guideline is suggested. We designed a check list in this form, where checking off all medical interventions is possible. Arrangement of the check list is according to our findings of most relevant and most achieved interventions.

Furthermore, we suggest establishing the practice of team leadership and the implementation of a team documenter at the maternity clinic. There are data about effect of multi-professional obstetric skills training on postpartum hemorrhage [10], but the concept of team leadership may be transferred from other subjects as trauma management or advanced life support where it has been well established. As Hjortdhal et al. published, leadership was perceived as an important component in trauma management [11]. From the experience with leadership in trauma management we may transfer the requirements of an ideal team leader to the department of obstetrics. The ideal leader must be highly experienced, should communicate clearly and radiate confidence [11] and should be comfortable directing and being responsive to other members of the team [12]. Therefore we recommend a senior obstetrician with extensive knowledge of postpartum hemorrhage or a senior anesthesiologist as a potential team leader. As an effective team leader is one that remained “hands off” delegating tasks wherever possible [13], we suggest establishing a team documenter as well. The team documenters should not only document all performed steps of the guidelines, but they should also document causes for not implementing specific therapeutic interventions such as contraindications and any complications that occur during the management process. In order to ensure the best performance of the team and to improve the care of patients with massive postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony, we suggest introducing the concept of a team leader and a team documenter into staff training.

5. CONCLUSIONS

1) In sum the guidelines were in use for 14% - 71%, which means that not all measures were necessary to achieve the best possible maternal outcome.

2) Even if 100% of all measures might have been used, it can be considered successful, if further morbidity was held low. However by using 100% of all measures, it might be assumed that the options were insufficient.

3) Every guideline for acute medical interventions needs to undergo evaluation for its effectiveness as we presented in our paper.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The study was approved by the ethics commission of the Medical University of Vienna and the General Hospital Vienna on January 29, 2010 (Number 1191/2009).

We want to thank Mag. Doris Kraushofer und Univ. Prof. Dr. Norbert Pateisky (Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Divison of Clinical Risk Managment and Patient Safety, Medical University Vienna) for their kindful help.

REFERENCES

- Ramanathan, G. and Arulkumaran, S. (2006) Postpartum hemorrhage. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada: JOGC, 28, 967-973.

- Jansen, A.J., van Rhenen, D.J., Steegers, E.A. and Duvekot, J.J. (2005) Postpartum hemorrhage and transfusion of blood and blood components. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, 60, 663-671. doi:10.1097/01.ogx.0000180909.31293.cf

- Varner, M. (1991) Postpartum hemorrhage. Critical Care Clinics, 7, 883-897.

- Anderson, J.M. and Etches, D. (2007) Prevention and management of postpartum hemorrhage. American Family Physician, 75, 875-882.

- Soltan, M.H., Faragallah, M.F., Mosabah, M.H. and AlAdawy, A.R. (2009) External aortic compression device: The first aid for postpartum hemorrhage control. The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research, 35, 453-458. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0756.2008.00975.x

- Roethlisberger, M., Womastek, I., Posch, M., Husslein, P., Pateisky, N. and Lehner, R. (2010) Early postpartum hysterectomy: Incidence and risk factors. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 89, 1040-1044. doi:10.3109/00016349.2010.499445

- Bouma, L.S., Bolte, A.C. and van Geijn, H.P. (2008) Use of recombinant activated factor VII in massive postpartum haemorrhage. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology, 137, 172-177. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2007.06.022

- Sheikh, L., Zuberi, N.F., Riaz, R. and Rizvi, J.H. (2006) Massive primary postpartum haemorrhage: Setting up standards of care. The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association (JPMA), 56, 26-31.

- Lain, S.J., Roberts, C.L., Hadfield, R.M., Bell, J.C. and Morris, J.M. (2008) How accurate is the reporting of obstetric haemorrhage in hospital discharge data? A validation study. The Australian & New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 48, 481-484. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.2008.00910.x

- Markova, V., Sorensen, J.L., Holm, C., Norgaard, A. and Langhoff-Roos, J. (2012) Evaluation of multi-professional obstetric skills training for postpartum hemorrhage. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 91, 346- 352.

- Hjortdahl, M., Ringen, A.H., Naess, A.C. and Wisborg, T. (2009) Leadership is the essential non-technical skill in the trauma team—Results of a qualitative study. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine, 17, 48.

- Georgiou, A. and Lockey, D.J. (2010) The performance and assessment of hospital trauma teams. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine, 18, 66.

- Cooper, S. (2001) Developing leaders for advanced life support: Evaluation of a training programme. Resuscitation, 49, 33-38. doi:10.1016/S0300-9572(00)00345-2

NOTES

*Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest and have not received any financial support.

#Corresponding author.

PIA® database is a trademark of GE Healthcare View Point Bildverabeitung GmbH, www.gehealthcare.com.