Open Journal of Psychiatry

Vol.3 No.2A(2013), Article ID:29761,6 pages DOI:10.4236/ojpsych.2013.32A002

Psychological effects of parenting children with autism prospective study in Kuwait

![]()

Kuwait Center for Autism, Kuwait

Email: *fido.abdo@gmail.com, *fido@hsc.edu.kw

Copyright © 2013 Abdullahi Fido, Samira Al Saad. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 24 January 2013; revised 28 February 2013; accepted 9 March 2013

Keywords: BDI; Autism; Mothers; Depression; Kuwait

ABSTRACT

Background: Recent reports suggest that the prevalence of autism in the Arab world ranges from 1.4 cases per 10,000 children in Oman to 29 per 10,000 children in the United Arab Emirates. While these rates are lower than those of the developed world, which are 39 per 10,000 for autism and 77 per 10,000 for all forms of autism spectrum disorders (ASD), it does not necessarily mean the condition is less prevalent in the Arab world. Objectives: Studies of parents with children with autism suggest that 35% - 53% of mothers with children show various degrees of depressive symptoms. However, many of these studies were conducted in western countries which still make little inferences about the prevalence of these stresses in Arab countries uncertain. No data are available on the use of the BDI on parents of children with autism in Kuwait. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the prevalence of parental depression in families of children with autism and in control families. Subjects and Methods: The participants in this study were 120 mothers and fathers of autistic children whose children were attending the Kuwait Autism Center at the time of this study. They were asked to complete the Arabic translated version of the Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI). It consists of 21 symptoms or attitudes commonly seen in patients suffering from depression. The symptoms are rated from “0” to “3” in intensity. The following cut-off points of depressive symptoms were used when interpreting the results in the present study: the range of scores from 0 to 9 indicates no depression, 10 - 20 dysphoria and over 20 depression. Results: The mean standard deviation scores for the mothers of autistic children were 21.2 ÷ 2.9 and 10.3 ÷ 2.1, (p = 0.001) for the control mothers respectively. No significant difference were observed across the samples of fathers other than slight increase for the autistic group. Marital status did not affect the number of mothers of the autism groups who had elevated depression scores, but single mothers in both groups had higher elevated depression scores than mothers living with partners, (x2 = 6.4, p < 0.005). Out of mothers with autistic children, 32.3% had depression and 41.5% had dysphoria while, 10% of control mothers had depression and 16% had dysphoria, x2 = 6.3 (p < 0.001). Conclusion: It is clear from our findings that mothers of autistic children have higher parenting-related stress and psychological distress as compared to controls. It is important to identify and offer appropriate psychiatric support for parents who are depressed since this is a serious problem, and would appear to have the potential to disrupt the family, parenting and child. While problem behavior is not a core element of autism, it might rise to the top of the issue that have to be dealt with first in a clinical setting.

1. INTRODUCTION

Recent reports suggest that the prevalence of autism in the Arab world ranges from 1.4 cases per 10,000 children in Oman to 29 per 10,000 children in the United Arab Emirates [1,2]. While these rates are lower than those of the developed world, which are 39 per 10,000 for autism and 77 per 10,000 for all forms of autism spectrum disorders (ASD), it does not necessarily mean the condition is less prevalent in the Arab world.

Caring for a family member with autism costs money and places a burden on family finances. A recent study [3] into the economic effect of autism in Egypt found that 83.3% - 91.3% of people with autism live at home with their families, which claim the scarcity, distance and unaffordable private residential placements, such as group homes, means they are left with little option but to keep their children with autism at home for an indefinite period, and well into their adult years.

Autism is different from all other disabilities, the characteristics of autism create additional stress for parents. Usually, the families are left alone to face the stressful challenges of raising a child with autism. In addition, families are also concerned about education and related services [4]. The impact autism presents huge challenge to parents. Some life changing issue identified by parents include the child’s resistance to change, their disparaging conduct and behaviour [5].

Previous studies [6,7] have found that parents of children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASP) report higher levels of child-related stress than parents of normally developing children. It has often been assumed that the extra stress of caring for a child with disabilities places parents at risk of developing psychological stresses.

Studies of parents with children with disabilities [8,9] suggest that 35% - 53% of mothers with children with disabilities pass cut-off scores for depression. However, many of these studies were conducted in western countries, which still make little inferences about the prevalence of depression in Arab countries uncertain. Depending on how depression is defined and assessed [10], lifetime prevalence rates for diagnosable depressive disorders in large population studies range from 2.6% to 12.7% in men, and 7% to 21% in women.

Even though the prevalence of parental depression varies between studies, several studies [11,12] dividing families into groups based on the child’s diagnosis have found that parents of autistic children report higher stress and more adjustment problems than parents of children with learning disabilities.

Apart from one study [13], little data are available on the use of the BDI on parents of children with autism as compared to other severe neurological and psychiatric disorders.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the prevalence of parental depression in families of children with autism and in control families.

2. SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The participants in this study were 120 mothers and fathers of autistic children whose children were attending the KCA at the time of this study. They were asked to complete the Arabic translated version of the Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI) [14]. This widely used instrument consists of 21 symptoms or attitudes commonly seen in patients suffering from depression (e.g. sadness, negative self-concept, sleep and appetite disturbances), and proved to be useful in detecting psychiatric symptoms in less articulate individuals. The symptoms are rated from “0” to “3” in intensity. The internal consistency for non-psychiatric subjects has yielded a mean coefficient α of 0.81, and the mean correlation of BDI with clinical ratings on the Hamilton Psychiatric Rating Scale for Depression has been found to be 0.74. However, another study [15] suggested caution with regard to the use of the term depression from a single administration of BDI. The following cut-off points of depressive symptoms were used when interpreting the results in the present study: the range of scores from 0 to 9 indicates no depression, 10 - 20 dysphoria and over 20 depression.

Single parenthood was defined as the presence of a single adult in the family regardless of whether the parent was divorced or, widowed. If two adults lived in the family, the family was considered to be a two-parent family, even if the other adult was not the biological parent of the child.

A written consent was obtained from all participants. Participants were informed that the project concerned research into psychological distress resulting from having and caring after their own children with autism and there no obligation to take part. They were also reassured that their responses to the questionnaire will not necessarily lead to the consideration for psychiatric referral. The study was approved by the research and ethics Committee of Kuwait University.

The control group was comprised of 125 parents of randomly selected children living in the same geographical area who had the same age and gender distribution as the study group. Parents who experienced looking after children with intellectual disabilities other than autism as well as parents with a past history of psychiatric disorder were excluded from the study. The Chi-Square statistical tests were used to assess the association of two categorical variables and the student t-test to compare between means of two continuous variables. Statistical significant difference was set at p = 0.05.

3. RESULTS

A cross-sectional questionnaire BDI was used to assess the psychological status of 120 parents of children with autism and a matched control sample of 125 parents of intellectually able children.

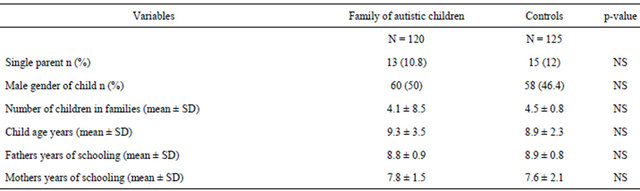

The socio-demographic characteristics of the subject studied are shown in Table 1.

There was no significant difference between the two samples in respect to age, education and occupation which indicates that the respondents were representative of the sample with regard to above parameters.

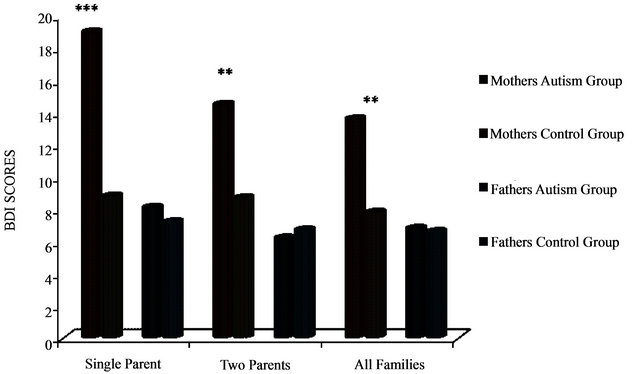

Figure 1 shows that the mothers of autistic children as a whole showed a significantly higher psychopathology in all BDI parameters. The mean standard deviation scores for the mothers of autistic children were 21.2 ± 2.9 and 10.3 ± 2.1 (p = 0.001), for the control mothers respectively. BDI scores were not affected by age, education and occupation. No significant differences were observed across the samples of fathers other than slight increase for the autistic group.

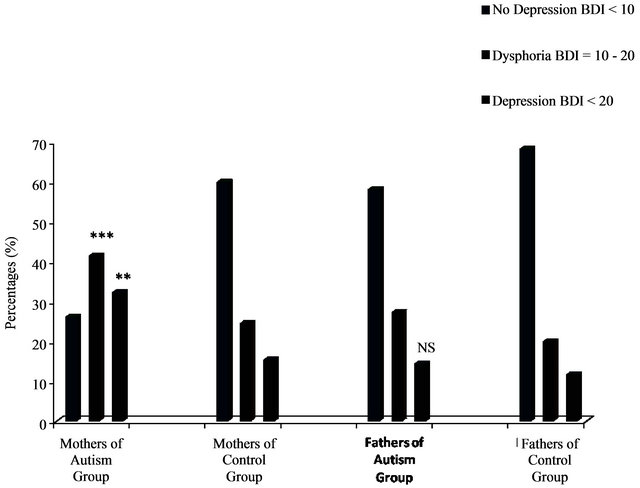

Within-sample comparisons between mothers and fathers illustrated the well established gender-depression relationship of higher mean scores for mothers in all two groups of families. Marital status did not affect the number of mothers of the autism groups who had elevated depression scores, but single mothers in both groups were found to have more highly elevated depression scores than mothers living with partners (x2 = 6.4, p < 0.005). Out of mothers with autistic children, 32.3% had depression and 41.5% had dysphoria while, 10% of control mothers had depression and 16% had dysphoria, x2 = 6.3 (p < 0.001). This difference persisted even when single mothers were excluded.

Marital status had no relation to depression scores in control mothers or fathers in either groups Figure 2.

4. DISCUSSION

The high level of psychiatric morbidity in parents of children with autism has been well documented [16,17], however, only a few studies have reported the relation between family characteristics such as marital status, for example, single parents have been excluded from several studies [18,19]. In this study, mothers of children with autism experienced more distress than mothers of children without autism, who in turn, experienced more distress than control fathers. It has been suggested [20] that high stress caused by the difficult behaviour of a child in combination with restrictions in personal life may be some of the factors that contribute to a high risk of depression in parents of children with autism.

Autism is a disorder that, in addition to intellectual

Table 1. Demographic variables in the two groups of families.

p > 0.05; NS = non significant.

Figure 1. Comparision of the BDI scores obtained by the autism groups and controls; ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.005.

Figure 2. Distribution of BDI scores in relation to diagnosis; ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.005.

disability, involves severe behavioural disturbances and a lack of social competence and responsiveness, factors all of which have been shown to increase parental stress [21,22].

Debate continues as to why mothers of children with autism are at an increased risk of depression while their spouses are not? It is possible that the consistent findings [23,24] of mothers experiencing more distress than fathers is caused by the fact that mothers take on a larger part of the extra care and practical work that the child with disabilities requires. They also tend to give up their job and feel unable to pursue their own interests. The mother’s self-competence may also be more related to the parenting role than father’s, and therefore, mothers may be more vulnerable when stress and difficulties arise in the parenting domain. It may also be that fathers show their distress in other ways than depression, which would suggest that we should include other measures of psychological health than depression in future studies. Other researchers [25,26] have also shown that mothers were particularly affected by behavioral problems demonstrated by the child, as well as his/her dependency, anxiety and poor communicative skills, while fathers, apart from communication problems, were most affected by the child’s physical disability and presence of other stressful life events (e.g. career-related or associated with family finances). As for behavioral problems, fathers were mostly distressed by the child’s externalizing problems, while mothers were more affected by the child’s regulatory problems. A supplement to these findings is the information that mothers perceived significantly more stigmatizing behaviors of other people than did fathers [27]. Thus, it would seem that mothers are more sensitive to hostile behavior of others towards the child than are fathers.

Many previous studies [28,29] have focused on the impact of having an autistic child on the family’s lifestyle and their socioeconomic status but, thus far, no study has discussed the cultural and religious component of having a child with intellectual disability. In the current study, the affected mothers have attributed their psychological impairment to more factors other than their social lifestyle. Kuwait society places great emphasis on healthy childbearing as an important goal for a family and motherhood is believed to be the most important role for women and, the perceived essence of women’s identity in Arab culture. Women are positioned in the genealogical tree as a member of the husband’s family and they are honored primarily for their ability to produce healthy sons [30]. Just like cancer and mental illnesses, Arab culture regards autism as a serious illness which causes are attributed to be as result of witchcraft or, punishment from God [31]. Some distressed individuals in this study tended to adopt a fatalistic attitude and accepted their condition at face value considering their suffering as God’s Immutable Will to test their characters.

Although, the overall educational level of Kuwaiti society has improved in the recent past, women are still subjected to traditional ways of thinking, which means that if the hope of becoming an effective mother ends in disappointment, not only the women, but also her parents would be ashamed to face the husband’s family.

In this sample, most mothers of autistic children felt they have failed as wives and some others were threatened with divorce or violence.

It is clear from our findings that mothers of autistic children have higher parenting-related stress and psychological distress as compared to controls. Outwardly, it might appear as if the psychological stressors exerted specific effects resulting in mental ill-health attributable these stressors. The relationship between psychological stressors and their consequences however, is not simply a cause-effect phenomenon. Recent research [32] has addressed the question of how coping resources interact to mediate or, buffer the potential harmful impact of psychosocial stressors.

This study has a few limitations: 1) The present study relies on one single administration of the BDI; 2) the collection of data by means of the questionnaire introduces the threat of selection bias. The validity of the findings is dependent on the individuals’ awareness of, and accuracy in, reporting level of distress; 3) it may not be suitable to compare parents of autistic children with parents of intellectually able children as both may have different psychological problems. A good comparison group would have been age-matched parents of children with learning disability. Consensual and legal matters in Kuwait precluded our ability to obtain such comparative data.

Although longitudinal studies would be ideal for this type of study, they are costly and time consuming, therefore the cross-sectional design was used and yielded correlation data which, however, provided heuristic implications for intervention therapy.

5. CONCLUSIONS

It is clear from our findings that mothers of autistic children have higher parenting-related stress and psychological distress as compared to controls. It is important to identify and offer appropriate psychiatric support for parents who are depressed since this is a serious problem, and would appear to have the potential to disrupt the family, parenting and child. While problem behavior is not a core element of autism, it might rise to the top of the issue that has to be dealt with first in a clinical setting.

At present, the social support networks for parents of autistic children in Kuwait are small and offer fewer opportunities for social support. Social support could be provided through the extended family, counseling, and support groups. Support groups are effective in reducing isolation and providing a forum for shared concerns.

Parent counseling should focus on the need of the entire family especially at critical periods, increase parent’s understanding of their child’s development, and enhance their parenting confidence and self-esteem.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to express thanks to Mrs Varghese for assisting with data analysis and the Kuwait Awqaaf Foudation for funding this project.

REFERENCES

- Al-Farsi, Y.M. and Al-Sharbati, M. (2007) Brief report: Prevalence of autistic spectrum disorders in the Sultanate of Oman. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 821-825. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-1094-8

- Eapen, V. (2011) Prevalence of pervasive developmental disorders in preschool children in the UAE. Journal of Tropical Paediatrics, 53, 202-205. doi:10.1093/tropej/fml091

- Lee Mendoza, R. (2010) The economics of autism in Egypt. American Journal of Economics and Business Administration, 2, 12-19. doi:10.3844/ajebasp.2010.12.19

- Dunn, M., Burbine, T. and Bowers, C. (2001) Moderators of stress in parents of children with autism. Community and Mental Health Journal, 37, 320-325. doi:10.1023/A:1026592305436

- Grey, D. (2002) Ten years on a longitudinal study of families of children with autism. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 27, 215-222. doi:10.1080/1366825021000008639

- Dumas, J., Wolf, L., Fisman, S. and Culligan, A. (1991) Parentingstress, child behaviour problems, and dysphoria in parents of children with autism, Down syndrome, behaviour disorders, and normal development. Exceptionality: A Research Journal, 2, 97-110. doi:10.1080/09362839109524770

- Veisson, M. (1999) Depression symptoms and emotional states in parents of disabled and non-disabled children. Social Behaviour and Personality, 27, 87-98. doi:10.2224/sbp.1999.27.1.87

- Blacher, J. and Lopez, S. (1997) Contributions to depression in Latina mothers with and without children with retardation: Implications for care-giving. Family Relations: Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies, 46, 325-334. doi:10.2307/585093

- Hoare, P., Harris, M., Jackson, P. and Kerley, S. (1998) Acommunity survey of children with severe intellectual disability and their families: Psychological adjustment, carer distress and the effect of respite care. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 42, 218-227. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2788.1998.00134.x

- Andrade, L. and Caraveo, A. (2003) Epidemiology of major depression. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 12, 3-21. doi:10.1002/mpr.138

- Sanders, J. and Morgan, S. (1999) Family stress and adjustment as perceived by parents of children with autism and Down’s syndrome: implication for intervention. Child and Family Behavioural Therapy, 19, 15-32. doi:10.1300/J019v19n04_02

- Ryde-Brandt, B. (1990) Anxiety and defence strategies in mothers of children with different disabilities. Journal of British Psychological Society, 63, 183-192.

- Beck, A.T., Steer, R.A. and Garbin, M.G. (1987) Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 8, 77-100. doi:10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5

- Kendall, P., Hollon, S., Beck, A.K., Hammen, C.L. and Ingram, R.E. (1987) Issues and recommendations regarding use of the beck depression inventory. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 11, 289-299. doi:10.1007/BF01186280

- Cameron, S., Dodson, L. and Day, D. (1991) Stress in parents of developmentally delayed and non-delayed preschool children. Canada’s Mental Health, 39, 13-17.

- Hodapp, R. and Dykens, E. (1997) Families with children with Prader-Willi syndrome; stress-support and relations to child characteristics. Journal of autism and Developmental Disorders, 27, 11-24. doi:10.1023/A:1025865004299

- Beckman, P. (1991) Comparison of mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of the effect of young children with and without disabilities. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 95, 585-595.

- Bristol, M., Gallagher, J. and Schopler, E. (1988) Mothers and fathers of young developmentally disabled and nondisabled boys: Adaptation and spousal support. Developmental Psychology, 24, 441-451. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.24.3.441

- Blacher, J. and Lopez, S. (1997) Contributions to depression in Latina mothers with and without children with retardation: Implications for care-giving. Family Relations: Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies, 46, 325-334. doi:10.2307/585093

- Estes, A., Munson, J., Dawson, G., Koehler, E., Zhou X.-H. and Abbott, R. (2009) Parenting stress and psychological functioning among mothers of preschool children with autism and developmental delay. Autism, 13, 375-387. doi:10.1177/1362361309105658

- Baker-Ericzen, M.J., Brookman-Frazee, L. and Stahmer, A. (2005) Stress levels and adaptability in parents of toddlers with and without autism spectrum disorders. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 30, 194-204. doi:10.2511/rpsd.30.4.194

- Bristol, M., Gallagher, J. and Schopler, E. (1988) Mothers and fathers of young developmentally disabled and nondisabled boys: Adaptation and spousal support. Developmental Psychology, 24, 441-451. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.24.3.441

- Moses, D. and Koegle, R. (1992) Stress profile for mothers and fathers of children with autism. Psychological Report, 71, 1272-1274

- Davis, N.O. and Carter, A.S. (2008). Parenting stress in mothers and fathers of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: Associations with child characteristics. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1278-1291. doi:10.1007/s10803-007-0512-z

- Bakér-Ericzen, M.J., Brookman-Frazee, L. and Stahmer, L. (2005) Stress levels and adaptability in parents of toddlers with and without autism spectrum disorders. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 30, 194-204. doi:10.2511/rpsd.30.4.194

- Farrugia, D. (2009) Exploring stigma: Medical knowledge and the stigmatization of parents of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Sociology of Health & Illness, 31, 1011-1027. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01174.x

- Gray, D.E. (2002) “Everybody just freezes. Everybody is just embarrassed”: Felt and enacted stigma among parents of children with high functioning autism. Sociology of Health & Illness, 24, 734-749. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.00316

- Olsson, B. and Hwang P. (2001) Depression in mothers and fathers of children with autism. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 45, 535-543. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2788.2001.00372.x

- Boyd, B.A. (2002) Examining the relationship between stress and lack of social support in mothers of children with autism. Focus on Autism & Other Developmental Disabilities, 17, 208-215. doi:10.1177/10883576020170040301

- el-Islam, M. ( 1994) Cultural aspects of morbidity fears in Qatari women. Social psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 29, 137-140.

- Fido, A. and Omar, Y.(1992) Affective Reaction to breast cancer diagnosis among Arab women. Medical Principles and Practice, 93, 72-76. doi:10.1159/000157451

- Dunn, M., Burbine, T. and Bowers (2001) Moderators of stress in parents of children with autism. Community and Mental Health Journal, 37, 320-325. doi:10.1023/A:1026592305436

NOTES

*Corresponding author.