Journal of Quantum Information Science

Vol.05 No.03(2015), Article ID:59629,13 pages

10.4236/jqis.2015.53011

Work Done on a Coherently Driven Quantum System

Issofa Nsangou, Lukong Cornelius Fai

Mesoscopic and Multilayer Structures Laboratory, Faculty of Science, Department of Physics, University of Dschang, Yaounde, Cameroon

Email: nsangou.issofa@yahoo.fr

Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 10 June 2015; accepted 13 September 2015; published 16 September 2015

ABSTRACT

We calculate the work done by a Landau-Zener-like dynamical field on two- and three-level quantum system by constructing a quantum power operator. We elaborate a general theory applicable to a wide range of closed-quantum system. We consider the dynamics of the system in the time domain  (where

(where  is the LZ transition time in the sudden limit) where the external pulse changes its sign and its action becomes relevant. The statistical work is evaluated in a period

is the LZ transition time in the sudden limit) where the external pulse changes its sign and its action becomes relevant. The statistical work is evaluated in a period  where

where . Our results are observed to be in good qualitative agreement with known results.

. Our results are observed to be in good qualitative agreement with known results.

Keywords:

Power Operator, Statistical Work, Landau-Zener Model, Level Crossing

1. Introduction

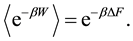

The pioneering work of Jarzynski establishes a non-trivial relation between the non-equilibrium work performed on a thermally insulated classical system and the change in its equilibrium free energy [1] . This expression became a coner stone of theories discussing non-equilibrium statistical mechanics and reads

(1)

(1)

Here,  is the work,

is the work,  where

where  and

and  are respectively the Boltzman constant and absolute temperature. The brackets

are respectively the Boltzman constant and absolute temperature. The brackets  denote the ensemble average over all possible realizations of the work

denote the ensemble average over all possible realizations of the work

(2)

(2)

where  is the total Hamiltonian and

is the total Hamiltonian and , the control protocol.

, the control protocol.  is the free energy difference between a reference equilibrium state of the system and a state achieved at time t by changing the protocol

is the free energy difference between a reference equilibrium state of the system and a state achieved at time t by changing the protocol  during the work. The Jarzynski equality holds irrespectively of whether the system ever reaches this reference equilibrium state. Even out of equilibrium, it proved to be applicable. The Jarzynski equa- lity has been extended to quantum regimes and experimentally tested [2] - [4] . It was accurately studied in single- electron transport [5] - [7] and molecular systems [8] . It was applied in Refs. [9] and [10] to produce the cooling of nanomechanical resonators and atoms.

during the work. The Jarzynski equality holds irrespectively of whether the system ever reaches this reference equilibrium state. Even out of equilibrium, it proved to be applicable. The Jarzynski equa- lity has been extended to quantum regimes and experimentally tested [2] - [4] . It was accurately studied in single- electron transport [5] - [7] and molecular systems [8] . It was applied in Refs. [9] and [10] to produce the cooling of nanomechanical resonators and atoms.

Though Equation (1) is extended to quantum systems, a key and natural question arised: does it still hold in a more realistic situation where the system remains in thermal contact with its environment while the forcing protocol is in action? An affirmative answer to this question was given by Crooks based on classical arguments [11] [12] . He proved this by showing that the Jarzyinski equality can be derived from a fluctuation theorem [11] [12] .

The experimental measurements of the proper free energy of a system lead to the average exponentiated work using Equation (1). This measurement is not always easily performed experimentally. The determination of the proper work has turned out to be a non-trivial task [13] - [15] . It attracted a lot of remarkable attentions and fed several scientist debates [13] - [18] . In order to find the work done by changing an external protocol on a quantum system, it is recommended to find the work operator [16] - [18] . Though this reasoning is quantum mechanically founded, it has quickly presented serious drawbacks [16] . The work does not depend on the instantaneous eigenstates of the system. It essentially depends on the process involved [17] [18] . Therefore, for open systems, the work cannot be defined by a local time-dependent operator. This is not an issue for closed systems [17] [18] .

The present paper is devoted to the calculation of the work done by an external field of constant amplitude on two- and three-level isolated systems. The systems are assumed to be thermally isolated from their environ- ments. We consider as in Ref. [19] that the work can be experimentally measured by the two-measurement process (TMP) [20] - [22] . The work corresponds to the change of the internal energy of the system. The TMP suggests a measurement of the internal energy between the initial and the final times  and

and

Here, the overdot denotes the time derivative. The average statistical work done during a period T on any quantum system is statistically defined as:

This formula is employed throughout this paper.

The paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, we present a general theory for calculating the work done on a coherently driven system. In Section 3, the theory is applied and tested on two-level system subjected to inter- band LZ transitions [23] -[26] . The same philosophy/strategy is extended to a three-level system yet subjected to LZ tunneling effects in Section 4.

2. Work and Fluctuations on Multi-Level Systems

The procedure for calculating the work done during transitions between Zeeman multiplet is illustrated. We consider systems on which act simultaneously a strong time-dependent diagonal field and a slowly varying perpendicular field. The prototype Hamiltonian describing these effects are written in the diabatic basis (basis of the eigen-states of the Hamiltonian in the absence of couplings) as follows:

The dynamical symmetry associated with (5) is referred to as

dependent control protocol

states

The protocols

During the work, the system passes through a sequence of several configurations (non necessarily equili- brated). If the states of the system are described by the reduced density matrix operator:

then, the statistical average of an arbitrary time-independent operator

(disordered average). For our case, the eigen-spectrum is discrete and characterized by the

the total wave-function

where

where H indicates the Heisenberg picture. The thermal and statistical averages are taken as:

Our goal is thus achieved once the evolution operator

The first and the second moments of the work whatever the process involved are respectively given in the Heisenberg picture by:

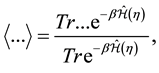

Figure 1. Sketch of diabatic energies of the Left and the Right drifts as a function of time. The drifts are coupled by a constant field.

and

Here, the power operator is basically a function of the fermionic occupation number

such that

As an important remark, evaluation of

and

where we have defined the transition amplitudes

and

The transition amplitude

The measurement of the

Once the eigenvalues are obtained, the transfer matrices for the intermediates trajectories

where

Between measurements, the system propagator describing a set of transitions through the j-crossing points is expressed as follows:

Consider the

Here,

transition is

Here,

A point of concern for introducing

with

The average occupation number

3. Quantum Work and Fluctuations on Two-Level System

We illustrate the theory presented above by considering the simplest case of the spin-1/2 two-level system.

3.1. The Model Hamiltonian

The model Hamiltonian considered is deduced from Equation (5) as,

The two instantaneous eigenvalues and eigenfunctions relevant to (22) should be evaluated. The results read:

where

is the level-separation energy and

where the normalization factors

For spin-1/2 considered, adiabatic

with

The projections

Here,

sentation,

Our analyzes of the work done on a two-level system are mainly performed in the limits

which is achieved in the sudden limit while

is the one obtained for the counterpart. It is instructive to note that the matrix

These data are helpful to evaluate the work done on a two-level system by an external field of constant amplitude.

3.2. Work and Fluctuations by the LZ Effect

The LZ process describes the dynamics of two states which come close by linear variation of a control protocol:

The energies

The time-evolution of the transition probability function during the rapid and slow drives show that nothing happens to the system before the crossing. It mainly remains in its initial state exhibiting an insensitivity to the external sweeping protocols

Considering the Hamiltonian (22), the power operator for a two-level system is explicitly evaluated as:

where

The average work done during a period T to transfer a population from the state

Figure 2. Energy diagram for a two-level system undergoing a tunneling LZ effect. The left panel corresponds to adiabatic trajectories. The right panel indicates the two diabatic trajectories associated with energies brought to the system by the protocol.

derived using the formula:

where

Here,

The average of the square fluctuations of the work,

The full propagator for the two-level system driven by the traditional LZ process (single crossing time

Here,

with

being the phase accumulated by the components of the wave-function from

where the angle

is the Stockes phase. The function

In the sudden limit of transition,

Substituting the instantaneous eigenstates (25) and (26) into the above expressions yields the transition amplitudes. Another way to find the transition amplitudes is to consider the projections of the states (43) and (44) onto the diabatic basis (

and

In these relations, projections of instantaneous eigenstates read:

In the regime

Thus, the statistical average works done on the two-state system are given by:

and

In principle, for the Landau-Zener drive,

An algebraic character can be associated with the quantum work. The work is antisymmetric by path reversal. By changing the protocol

In addition, it should also be noted that

Because of the link between work and heat, the properties in Equations (52) and (53) can be attributed to the heat.

Recall that

A particular characteristic for a quantum work similar to that of classical work should be pointed out. Basi- cally, the work done on a classical system does not depend on the followed path but only on the initial and final positions. Relations (50) and (51) show a contrasted situation in the regime of sudden transitions. Namely, the work done on a quantum two-level system does not depend on the followed path. It does not depend yet on the initial and the final states. The initial state can be chosen arbitrary, the efficiency remaining the same.

In the regime

The occupation probability,

plete transfer. Both diabatic states remain constantly coupled and the total population is preserved,

An alternative way to find the work done on a system is defined through the two-measurement process (TMP) [20] - [22] . The internal energy

ning and at the end of the evolution. The work done during the process is predetermined by the corresponding energy difference,

procedure for a rapid LZ drive process(non-adiabatic evolution). The work is then defined as:

Considering the Hamiltonian

As already shown, the transition amplitudes do not depend on time in the sudden limit. The work is obtained as follows:

This result exactely coincides with the one derived from Equation (35) under the same assumptions.

From a quantum mechanical view point it is more convenient to find the Hamiltonian difference

which is nothing but the power operator in Equation (33).

4. Quantum Work and Fluctuations on Three-Level System

4.1. The Model Hamiltonian

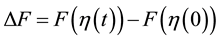

Here, an additional level position is present. It might evolve with time or not. States are coupled by this intermediate position via a constant coupling. The model is of the form:

In this representation,

The associated eigenvalues are expressed as follows

Figure 3. Sketch of diabatic energies of the Left and the Right drifts as a function of time. The drifts are coupled by a constant field.

Here,

with

where

and

Similarly, we have defined

The instantaneous eigenfunctions are calculated. The results are written as follows:

where

Here,

and

The normalization factor

where

For spin-1, we do

We obtained this matrix by direct calculations. Indeed, the angle

the diabatic basis are of the form (28), namely,

relations serve for derivation of transition amplitudes as we did for the case of two-level.

A projection matrix can be constructed. The extreme limits

and

for adiabatic limit. As for the case of two-level, these two matrices obey

4.2. Work and Fluctuations by the LZ Effect

The definition of the work given in the first section is used. The power operator is expressed here as:

where,

The average of the work can be evaluated with aid of the formula:

The average

and

The components

These representations help to approximate the work done on a three-level system for the sudden and adiabatic limits of transition. For instance, in the sudden limit, it can be shwon that, populations transfered between the three levels correspond to those for spin-1 LZ problem:

The works in (82) are decomposed as follows:

and correspond each to a diabatic state. As already explained,

been transferred from the diabatic states

Considering the works done on two-level systems, that for three-level in Equations (86)-(88) are the sum of works between intermediate diabatic positions. These works could be constructed intuitively considering intermediate works separately.

Equations (86)-(88) can be transformed with the aid of the components of the matrix in Equation (85). Thus, one obtains:

We have exploited the fact that

5. Conclusions

We have presented a theory for evaluating the work done on a multi-level system. Two particular cases (two- and three-level) are considered and permit to illustrate the theory. The obtained results for two-level spin-1/2 system were shown to be simple functions of the Landau-Zener probability function. Thus, the work depends on control protocol which can be experimentally manipulated. We have demonstrated that forward work and backward were absolutely identical and differ algebraically by a sign in the sudden limit. The efficiency of the work done has been observed as being independent on the initial state chosen. It has been pointed out that an adiabatic variation of the protocol cannot lead to a complete population transfer when the system is isolated from its environment. The half of the initial population corresponds to the maximum of the population trans- ferable. Both states remain constantly coupled. If one allows the internal energy of such a system to flow out of it or an external energy source to flow towards the system, it will be entangled and its states will no longer be expressible as linear superposition of the states of the subsystem. An equilibrium would not be achieved. The system will mostly evolve out of equilibrium. The work done will be accompanied by an additional work due to the perturbation:

Here,

For three-level system on the other hand, the work to be done in order to achieve a transfer of population from one of the upper (lower) to another lower (upper) diabatic states appeared as being the sum of intermediate works performed independently.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank M. Tchoffo, A. J. Fotue, Kenfack Sadem and F. Ngoran for careful reading of the manuscript and valuable suggestions.

Cite this paper

IssofaNsangou,Lukong CorneliusFai, (2015) Work Done on a Coherently Driven Quantum System. Journal of Quantum Information Science,05,89-102. doi: 10.4236/jqis.2015.53011

References

- 1. Jarzynski, C. (1997) Nonequilibrium Equality for Free Energy Differences. Physical Review Letter, 78, Article ID: 2690.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.78.2690 - 2. Sagawa, T. and Ueda, M. (2008) Second Law of Thermodynamics with Discrete Quantum Feedback Control. Physical Review Letter, 100, Article ID: 080403.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.080403 - 3. Morikuni, Y. and Tasaki, H. (2011) Quantum Jarzynski-Sagawa-Ueda Relations. Journal of Statistical Physical, 143, 1-10.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10955-011-0153-7 - 4. Toyabe, S., Sagawa, T., Ueda, M., Muneyuki, E. and Sano, M. (2010) Experimental Demonstration of Information-to-Energy Conversion and Validation of the Generalized Jarzynski Equality. Nature Physics, 6, 988-992.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nphys1821 - 5. Averin, D.V. and Pekola, J.P. (2011) Statistics of the Dissipated Energy in Driven Single-Electron Transitions. Euro Physics Letter, 96, Article ID: 67004.

- 6. Küng, B., Rössler, C., Beck, M., Marthaler, M., Golubev, D.S., Utsumi, Y., Ihn, T. and Ensslin, K. (2012) Irreversibility on the Level of Single-Electron Tunneling. Physical Review X, 2, Article ID: 011001.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/physrevx.2.011001 - 7. Saira, O.-P., Yoon, Y., Tanttu, T., Möttönen, M., Averin, D.V. and Pekola, J.P. (2012) Test of the Jarzynski and Crooks Fluctuation Relations in an Electronic System. Physical Review Letter, 109, Article ID: 180601.

- 8. Alemany, A., Ribezzi, M. and Ritort, F. (2011) Recent Progress in Fluctuation Theorems and Free Energy Recovery. AIP Conference Proceedings, 1332, 96.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.3569489 - 9. Hopkins, A., Jacobs, K., Habib, S. and Schwab, K. (2003) Feedback Cooling of a Nano-Mechanical Resonator. Physical Review B, 68, Article ID: 235328.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.68.235328 - 10. Steck, D., Jacobs, K., Mabuchi, H., Bhattacharya, T. and Habib, S. (2004) Quantum Feedback Control of Atomic Motion in an Optical Cavity. Physical Review Letter, 92, Article ID: 223004.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.92.223004 - 11. Crooks, G.E. (1998) Nonequilibrium Measurements of Free Energy Differences for Microscopically Reversible Markovian Systems. Journal of Statistical Physics, 90, 1481-1487.

- 12. Crooks, G.E. (1999) Excursions in Statistical Dynamics. PhD Thesis, University of California, Berkeley.

- 13. Campisi, M., Talkner, P. and Hänggi, P. (2010) Fluctuation Theorems for Continuously Monitored Quantum Fluxes. Physical Review Letters, 105, Article ID: 140601.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.105.140601 - 14. Campisi, M., Hänggi, P. and Talkner, P. (2011) Colloquium. Quantum Fluctuation Relations: Foundations and Applications. Review Modern Physics, 83, 771-791.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/revmodphys.83.771 - 15. Campisi, M., Talkner, P. and Hänggi, P. (2011) Influence of Measurements on the Statistics of Work Performed on a Quantum System. Physical Review E, 83, Article ID: 041114.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/physreve.83.041114 - 16. Pekola, J.P., Solinas, P., Shnirman, A. and Averin, D.V. (2013) Calorimetric Measurement of Work in a Quantum System. New Journal of Physics, 15, Article ID: 115006.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/15/11/115006 - 17. Chernyak, V. and Mukamel, S. (2004) Effect of Quantum Collapse on the Distribution of Work in Driven Single Molecules. Physical Review Letters, 93, Article ID: 048302.

- 18. Allahverdyan, A.E. and Nieuwenhuizen, T.M. (2005) Fluctuations of Work from Quantum Subensembles: The Case against Quantum Work-Fluctuation Theorem. Physical Review E, 71, Article ID: 066102.

- 19. Solinas, P., Averin, D.V. and Pekola, J.P. (2013) Work and Its Fluctuations in a Driven Quantum System. Physical Review B, 87, Article ID: 060508(R).

- 20. Engel, A. and Nolte, R. (2007) Jarzynski Equation for a Simple Quantum System: Comparing Two Definitions of Work. Europhysics Letters, 79, Article ID: 10003.

- 21. Talkner, P., Lutz, E. and Hänggi, P. (2007) Fluctuation Theorems: Work Is Not an Observable. Physical Review E, 75, Article ID: 050102.

- 22. Esposito, M., Harbola, U. and Mukamel, S. (2009) Nonequilibrium Fluctuations, Fluctuation Theorems, and Counting Statistics in Quantum Systems. Review Modern Physics, 81, 1665-1702.

- 23. Landau, L.D. (1932) On the Theory of Transfer of Energy at Collisions II. Physikalische Zeitschrift der Sowjetunion, 2, 46-51.

- 24. Zener, C. (1932) Non-Adiabatic Crossing of Energy Levels. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series A, 137, 696-702.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1932.0165 - 25. Stückelberg, E.C.G. (1932) Theory of Inelastic Collisions between Atoms. Helvetica Physica Acta, 5, 369-423.

- 26. Majorana, E. (1932) Atoms Oriented in a Variable Magnetic Field. Nuovo Cimento, 9, 43-50.

- 27. Pokrovsky, V.L. and Sinitsyn, N.A. (2004) Spin Transitions in Time-Dependent Regular and Random Magnetic Fields. Physical Review B, 69, Article ID: 104414.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.69.104414 - 28. Lifshitz, E.M. and Landau, L.D. (1981) Quantum Mechanics: Non-Relativistic Theory. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

- 29. Vilenkin, N. and Klimyk, A. (1991) Representation of Lie Group and Special Functions. Kluwer, Dordrecht.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-3538-2 - 30. Erdelyi, A., Magnus, W., Oberhettinger, F. and Tricomi, F.G. (1953) Higher Transcendental Functions. McGraw-Hill, New York.

- 31. Kenmoe, M.B., Phien, H.N., Kiselev, M.N. and Fai, L.C. (2013) Effects of Colored Noise on Landau-Zener Transitions. Physical Review B, 87, Article ID: 224301.

- 32. Carroll, C.E. and Hioe, F.T. (1986) Generalisation of the Landau-Zener Calculation to Three Levels. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General, 19, 1151-1161.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0305-4470/19/7/017