Art and Design Review

Vol.03 No.03(2015), Article ID:58494,6 pages

10.4236/adr.2015.33010

Two Extraordinary New Museums in South-Eastern China

Vladimir J. Konečni

Department of Psychology, University of California, San Diego, USA

Email: vkonecni@ucsd.edu

Copyright © 2015 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 6 July 2015; accepted 28 July 2015; published 31 July 2015

ABSTRACT

Various architectural and aesthetic matters are discussed in this analytic commentary regarding two highly significant new museums in South-Eastern China in the ancient cities of Suzhou (architect: I. M. Pei) and Ningbo (architect: Wang Shu). Questions regarding the aesthetics of innovation, the public acceptance of nontraditional work in city cores, and the determinants and logistics of real-world decision-making in these domains are also addressed.

Keywords:

Aesthetics in Architecture, New Museums in China, Suzhou Museum 2006, Ningbo Museum 2008, I. M. Pei in Suzhou, Wang Shu in Ningbo, Wang Shu’s Pritzker Prize, Architects’ Violation of Traditional Style, Experimentation in Architecture, Interesting versus Pleasing in Architecture, Recycling Materials in Architecture

1. Introduction

As a function of its rapid economic progress, new or outstandingly renovated infrastructure has emerged in China―in profusion and quality of which even the most developed countries may be envious. The most impressive fact for even a regular visitor from abroad is the remarkable growth in the number of space-age airports, massive, elegantly interrelated train and bus stations, cutting-edge subway and other transportation systems, comparatively inexpensive hotels of genuine five-star caliber, and, last but certainly not least, superb new museums. A great deal of money is spent in China on culture, perhaps especially on museum culture. Funds are spent intelligently, as befits a vast land with an astonishingly long cultural history, but―and this leads to a mixture of admiring wonder and slight irritation on the part of western critics with negative preconceptions or agendas―there is also an at least occasional openness to rather radical experimentation.

In general, the most renowned architects are not the ones who permit themselves the greatest amount of flexibility and risk-taking in projects that are “close to home”. They may be burdened by a sense of responsibility that is reflected in the insistence not to betray or distort the traditionally envisaged local historical character and ambience. This, of course, does not mean that the best among them does not create superlative works that are a timeless improvisation on both the local and the all-Chinese―on the Buddhist, Taoist, Confucian, and even the (post)-modern.

2. The Suzhou Museum

A brilliant example is the relatively new museum in Suzhou (Barbosa, 2006; Ivy, 2008) , which was designed in 2006 by I. M. Pei (Ieoh Ming Pei) ( Photo 1 ). Suzhou, located in the wealthy province of Jiangsu, is a famous ancient city of countless waterways, delicate bridges, and the specifically Chinese ornamental “philosophical” gardens (Fang, 2010; Henderson, 2012; Li, 2006) . Pei was born in 1917 in Guangzhou in southern China, but the origin of his family is in Suzhou and he spent some formative years of his youth there. In many of his works throughout the world, Pei was far bolder and controversial than in Suzhou with respect to the local architectural and aesthetic tradition, for example, in the case of his ground-breaking glass pyramid at the Louvre (Goldberger, 1989; Jodidio, 2009). In the entire design of the Suzhou museum, but especially its garden, as well as in the superb manner in which he related the exterior design to the interior features of the museum, Pei achieved an architectural masterpiece, inspired by the locality―but, essentially, with a minimum of experimentation ( Photo 2 and Photo 3 ).

By the dominant uncompromising whiteness of its exterior, the museum opposes the off-white-grey color palette of ancient Suzhou and alludes to, or references, other locales in the world, but by the design of each significant structural detail, and of the rocks, water, and vegetation in the garden, it is deeply Buddhist. The Suzhou museum is an epitome of modesty and respect for the local, an attitude that this magisterial architectural aesthete has brought to perfection ( Photo 4 ).

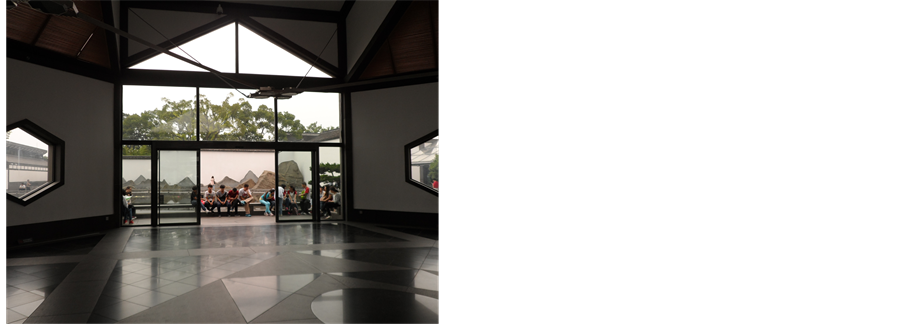

Photo 1. The entrance hall. Ó Vladimir J. Konečni.

Photo 2. A part of the garden. Ó Vladimir J. Konečni.

Photo 3. Exquisite subtlety in design. Ó Vladimir J. Konečni.

Photo 4. The garden pavilion. Ó Vladimir J. Konečni.

3. The Ningbo Museum of History

Some 250 kilometers southeast of Suzhou is another ancient city, Ningbo, in the almost as rich province of Zhejiang. Ningbo was long ago more prominent than even Shanghai, its close neighbor to the north, in maritime trade. It is a pleasant city, with lush parks and pretty ponds adjacent to its three rivers, but the building of greatest contemporary interest is located some fifteen kilometers south of the old city center, amidst nondescript skyscrapers in the new district of Yinzhou: here one finds the extraordinary museum of history and art of the Ningbo region, opened in December of 2008 (Pogrebin, 2012; Wöhler, 2010) . The museum has some 80,000 items, rare objects of bronze, porcelain, jade, gold, and silver, as well as superb bamboo carvings. The collections are impressive, but it is fair to say that they do not surpass those in major regional museums in other parts of China. What makes the new museum in Ningbo unique is its innovative architecture, a wondrous mix of the modest and the grandiose. The chief architect, Wang Shu (born in 1963), received the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize

for 2012, becoming the first citizen of P. R. China to have achieved this (Pei received the same prize in 1983, but as a naturalized U. S. citizen). Even more than in the case of most buildings, spending time around and in the Ningbo museum is indispensable in order to judge properly and fairly the ambivalent qualities and appeal of its architecture. Indeed, jurors for the Pritzker personally visit all nominated candidates ( Photo 5 ).

It is safe to assume that very few visitors remain neutral or uncommitted in their sentiments and opinions about this monumental, multifaceted work of art―be it love at first sight (as in the case of this article's author, among many others), or admiration after resistance and conflict (as, reputedly, has been true of many citizens of Ningbo), or a permanent rejection of the fortress-like architectural mammoth with its irregularly shaped and randomly placed windows, and its remarkable but incomprehensible, and seemingly unnecessary and affected, tilts and outward slopes (as is likely to be true of many other visitors) ( Photo 6 ).

Photo 5. The only side of the building with colorful vegetation (late May 2015). Ó Vladimir J. Konečni.

Photo 6. A small free-standing building adjacent to the main one. Ó Vladimir J. Konečni.

Brick, wood, cemented bamboo, and ceramic tiles―traditional materials not just in the Ningbo area but in the entire enormous Yangtze delta―are innovatively combined in Wang Shu's building. Nevertheless, one doubts that the citizens of Ningbo, as some have suggested, intuitively recognized and were moved by the traces of their region’s building heritage. Nor does it seem likely that the building awakens some remote associations to Buddhist ideas in design. On the contrary, one seems entitled to suggest that the resistance on the part of many citizens of Ningbo has had its origin, foreseeably and rationally, in the fact that so very little in this magnificent, yet unapologetically austere and bizarre huge object, has anything of traditional Chinese aesthetics in it.

The Pritzker Prize largely silenced local critics, which international fame tends to do, rightly or wrongly. Prior to getting the building go-ahead, Wang Shu made valiant efforts of persuasion in town hall meetings and through personal contacts with Ningbo citizens, in the manner first developed by Christo (Javacheff) in his “wrapping” projects worldwide (e.g., Tomkins, 1977; Wilson, 1985 ). One of Wang’s major “selling points” throughout has been that the museum would largely be built of discarded and recycled materials, especially bricks and tiles. How much an ecological argument could overcome, in this case and others elsewhere, the resistance of those opposed to the building on the grounds of aesthetics and tradition, is hard to discern. In the language of psychological aesthetics, the key proposition is that the Ningbo building is highly interesting rather than pleasing to the eye. This is an important distinction that has been theoretically developed and empirically studied for various kinds of visual stimuli in the laboratory, as well as in archival research (e.g., Berlyne, 1971; Konečni, 2015 ). In the “real world,” anecdotally, worldwide past experience in architecture and urban design has consistently shown that city-dwellers’ prolonged exposure to a work transforms, in the great majority of cases, “mere interest,” and even dislike, into pleasure and eventually results in judgments of the work “as beautiful” and “ours” (or beautiful because it is ours).

With regard to the question of local acceptance and Wang’s personal views, it is also clear that the choice of the museum’s distant location, in a forlorn part of a district without a historical pedigree, was intentional―and very astute. Much as the average visitor to the museum may not be pleased to have to go to Yinzhou, and much as the surrounding area contributes no satisfying context at all to the museum, Chinese or otherwise, the sterile, lifeless, modernistic wasteland complements the building’s austerity. More importantly, no traditional buildings either compete with Wang’s or had to be destroyed to create the space. Thoughtless destruction of old buildings and neighborhoods has been rampant and aggressively carried out in contemporary China, most visibly in Beijing for the 2008 Olympics (Ouroussoff, 2008; Yardley, 2008), but also elsewhere; and both Wang Shu and Lu Wenyu, his wife and longtime partner in architecture (see the “ Amateur Architecture Studio ” web site in References; and, e.g., Russell, 2013 ), have long been committed opponents of the practice1. Local critics of Wang’s building were, yet again, cleverly appeased by the absence of potential destruction in some historic section of Ningbo proper, near the rivers, canals, and famous bridges. Clearly, at least some architects and city planners learned something, for example, from the tumultuous erection of Centre Georges Pompidou in the Beaubourg area of Paris by Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano in 1977 (cf. Levy, 2007; Poderos, 2003 ). There, not only was a “monster” built (which was Parisians’ sentiment at the time―witness, however, their love of “Beaubourg” now), but the beloved food markets Les Halles, and the social habitat engulfing them, with genuine historical significance, were forcibly removed.

Nevertheless, one continues to inquire: why these strange shapes, tilts, and slopes of which many are without function? (And while much building material may have been trouvé, labor is not any longer that cheap in China.) In response, while evading the question of cost, one should note that the interior of the building is not “experimental,” and that the sober, conventional arrangement of the enormous display space must have played an additional important part in appeasing the locals―which was important in view of the museum’s primary obligation to celebrate the traditions, history, and customs of Ningbo. One also wishes to ask: has Wang Shu gone too far, beyond reason, in how massive and “weird” he made the building? ( Photo 7 )

There is no good answer to this, except that a very large number and broad range of specialized art-related activities occur in the place. The building’s alleged allusions to the shapes of ships’ prows and forms of nearby mountains seem ad hoc, too convenient, and far-fetched. When one looks carefully at some of the gratuitous aspects of the building’s silhouette from various vantage points, one concludes that Wang’s design of various façades managed to achieve the almost total freedom that an abstract painter has―but paint and canvas are cheap ( Photo 8 ).

Photo 7. Not easy to stroll around the building. Ó Vladimir J. Konečni.

Photo 8. The main entrance. Ó Vladimir J. Konečni.

4. Conclusion

I. M. Pei came back to his family’s ancestral home of Suzhou and was under enormous pressure to build a place, in the ancient city core, which would be able to house Suzhou’s sublime cultural artifacts of several thousands of years. He was faced with area limits, height limits, water table issues, and the fact that the museum would have as its immediate neighbor one of the most famous gardens in all of China, Zhuozheng Yuan (“Humble Administrator’s Garden”). Pei built a spectacular building that does not violate ancient Suzhou, fits in, yet splendidly stands out―by color and improvisations in design. In 2006, Pei was 89. A great architect, given freedom, objective constraints, and internal constraints of respect over self-promotion, chose a delicate compromise solution.

As for the self-questioning possibly experienced by those who are inexplicably, even to themselves, yet inextricably, drawn to the Ningbo Museum, the most convincing rationale they may adopt is that this building is not only architecture, but a new visual magic needed for our blasé time. As is characteristic of other key moments in the history of art, what is accomplished in Ningbo is the optimal connection of old and new, a precisely chosen degree of innovation that creates conflict, but is able to attract more than it repels. As the internationally renowned 93-year-old Serbian architect Mihajlo Mitrović recently told the author of this article in Belgrade (Serbia), his eyes bright about the future possibilities in architecture, “I. M. Pei has been spectacular, but the time of Wang Shu’s marvelous invention―though extraordinarily expensive―is still to come, and his influence on Chinese and world architecture will be even greater”.

Cite this paper

Vladimir J.Konečni, (2015) Two Extraordinary New Museums in South-Eastern China. Art and Design Review,03,76-82. doi: 10.4236/adr.2015.33010

References

- 1. Amateur Architecture Studio http://www.chinese-architects.com/en/amateur

- 2. Barbosa, D. (2006). I.M. Pei in China Revisiting Roots. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/09/arts/design/09pei.html?_r=1&

- 3. Berlyne, D. E. (1971). Aesthetics and Psychobiology. New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- 4. Fang, X. (2010). The Great Gardens of China: History, Concepts, Techniques. New York, NY: The Monacelli Press.

- 5. Hawthorne, C. (2012). Pritzker Prize Goes to Wang Shu, 48-Year-Old Chinese Architect. The Los Angeles Times. http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/culturemonster/2012/02/pritzker-prize-wang-shu-architect.html

- 6. Henderson, R. (2012). The Gardens of Suzhou. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- 7. Ivy, R. (2008) Suzhou Museum. Architectural Record, China Issue. http://archrecord.construction.com/ar_china/BWAR/0804/0804_suzhou/0804_suzhou.asp

- 8. Kone?ni, V. J. (2015). Emotion in Painting and Art Installations. American Journal of Psychology, 128, 305-322. http://dx.doi.org/10.5406/amerjpsyc.128.3.0305�

- 9. Levy, B.-H. (2007). A Monument of Audacity and Modernity. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2007/oct/09/architecture.paris

- 10. Li, Z. (2006). The Classical Gardens of Suzhou: Travel through the Middle Kingdom. Shanghai: Better Link Press.

- 11. Poderos, J. (2003). Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. New York: Prestel Publishing.

- 12. Pogrebin, R. (2012). For First Time, Architect in China Wins Top Prize. The New York Times,. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/28/arts/design/pritzker-prize-awarded-to-wang-shu-chinese-architect.html

- 13. Russell, J. (2013). Wang Shu, China’s Champion of Slow Architecture. Bloomberg News. http://www.bloomberg.com/bw/articles/2013-06-13/wang-shu-chinas-champion-of-slow-architecture

- 14. Tomkins, C. (1977). Running Fence. The New Yorker, 43-81. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1977/03/28/running-fence

- 15. Wilson, W. (1985). Christo’s Pont Neuf Project in Curious Paris—It’s a Wrap. The Los Angeles Times. http://articles.latimes.com/1985-09-24/entertainment/ca-18784_1_christo

- 16. W?hler, T. (2010). Ningbo Museum by Pritzker Prize Winner Wang Shu. The Architectural Review. http://www.architectural-review.com/ningbo-museum-by-pritzker-prize-winner-wang-shu/5218020.article�

NOTES

1There is some discussion in architectural circles to the effect that Lu Wenyu should have shared the Pritzker with Wang Shu (e.g., Hawthorne, 2012 ). The argument seems insufficiently substantiated and is found mostly in blogs and gossip columns with a political agenda.