Open Journal of Statistics

Vol.04 No.10(2014), Article ID:51470,11 pages

10.4236/ojs.2014.410077

Regularization and Estimation in Regression with Cluster Variables

Qingzhao Yu1, Bin Li2

1School of Public Health, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, LA, USA

2Department of Experimental Statistics, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA

Email: qyu@lsuhsc.edu, bli@lsu.edu

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 14 October 2014; revised 5 November 2014; accepted 15 November 2014

ABSTRACT

Clustering Lasso, a new regularization method for linear regressions is proposed in the paper. The Clustering Lasso can select variable while keeping the correlation structures among variables. In addition, Clustering Lasso encourages selection of clusters of variables, so that variables having the same mechanism of predicting the response variable will be selected together in the regression model. A real microarray data example and simulation studies show that Clustering Lasso outperforms Lasso in terms of prediction performance, particularly when there is collinearity among variables and/or when the number of predictors is larger than the number of observations. The Clustering Lasso paths can be obtained using any established algorithm for Lasso solution. An algorithm is proposed to construct variable correlation structures and to compute Clustering Lasso paths efficiently.

Keywords:

Clustered Variables, Lasso, Principal Component Analysis

1. Introduction

We are often interested in finding important variables that are significantly related to the response variable and can be used to predict quantities of interest in regressions and classification problems. Important variables are often shown in clusters where variables in the same cluster are highly correlated and have similar pattern relating to the response variable. For example, a major application of microarray technology is to discover important genes and pathways that are related to clinical outcomes such as the diagnosis of a certain cancer. Typically, only a small proportion of genes from a huge bank have significant influence on the clinical outcome of interest. In addition, expression data frequently have cluster structures: the genes within a cluster often share the same pathway and are therefore similarly related to the outcome. When regression is adapted in this setting, we often face the challenge from multi-collinearity of covariates. An ideal variable selection procedure should be able to find all genes of important clusters rather than just some representative genes from the clusters. Typically, two characteristics, pointed out by [1] , evaluate the quality of a fitted model: accuracy of prediction on new data and interpretation of the model. For the latter, the sparse model with fewer selected covariates is preferred for interpretation due to its simplicity. However, when multiple variables share the same mechanism for explaining the response, all the involved variables should have an equal chance of being selected, and should exhibit the same relationship to the outcome in the fitted model, for scientific reasoning.

It is well known that the ordinary least square estimate (OLS) in linear regression often performs poorly when some of the predictors are highly correlated. OLS would generate unstable results where the estimates have inflated variances. Regularizations have been proposed to improve OLS. For example, ridge regression [2] penalizes the model complexity by the  penalty of the coefficients. This method was proposed to solve the collinearity problem by adding a constant to the diagonal terms of

penalty of the coefficients. This method was proposed to solve the collinearity problem by adding a constant to the diagonal terms of , where

, where  is the observation or design matrix. Ridge regression stabilizes the estimates through the bias-variance trade-off. It can often improve the predictions but cannot select variables. [3] proposed the Lasso method by imposing an

is the observation or design matrix. Ridge regression stabilizes the estimates through the bias-variance trade-off. It can often improve the predictions but cannot select variables. [3] proposed the Lasso method by imposing an  -penalty on the regre- ssion coefficients. Lasso is a promising method, as it can improve prediction and produce sparse models simultaneously. However, when high correlations among predictors are present, the predictive performance of Lasso is dominated by ridge regression [3] . Moreover, when there is a cluster of variables, in which each variable associates with the response variable similarly, Lasso tends to arbitrarily select one variable from the cluster instead of identifying the cluster [1] ; see also Section 2 for more discussion. Elastic Net, proposed by [1] , combines both

-penalty on the regre- ssion coefficients. Lasso is a promising method, as it can improve prediction and produce sparse models simultaneously. However, when high correlations among predictors are present, the predictive performance of Lasso is dominated by ridge regression [3] . Moreover, when there is a cluster of variables, in which each variable associates with the response variable similarly, Lasso tends to arbitrarily select one variable from the cluster instead of identifying the cluster [1] ; see also Section 2 for more discussion. Elastic Net, proposed by [1] , combines both  and

and  penalties of the coefficients as the regularization criterion. The method is promising in that it encourages cluster effects and shows improved predictive performance over Lasso. Elastic Net can automatically choose cluster variables and estimate parameters at the same time. Many other methods can be used to choose clustered variables, such as principal component analysis (PCA). [4] defined “eigen-arrays” and “eigen-genes” in this way. But PCA can not choose sparse models. [5] proposed sparse principal component analysis (SPCR), which formulated PCA as a regression-type optimization problem, and then obtained sparse loadings by imposing the Elastic Net constraint. SPCR can successfully yield exact zero loadings in principal components. However, for each principal component, a regularization parameter has to be selected, which results in an overwhelming computational burden when the number of parameters is large. Other penalized regression methods have been proposed for group effect [6] - [13] . However, these methods either pre-suppose a grouping structure or assume that each predictor in a group shares an identical regression coefficient.

penalties of the coefficients as the regularization criterion. The method is promising in that it encourages cluster effects and shows improved predictive performance over Lasso. Elastic Net can automatically choose cluster variables and estimate parameters at the same time. Many other methods can be used to choose clustered variables, such as principal component analysis (PCA). [4] defined “eigen-arrays” and “eigen-genes” in this way. But PCA can not choose sparse models. [5] proposed sparse principal component analysis (SPCR), which formulated PCA as a regression-type optimization problem, and then obtained sparse loadings by imposing the Elastic Net constraint. SPCR can successfully yield exact zero loadings in principal components. However, for each principal component, a regularization parameter has to be selected, which results in an overwhelming computational burden when the number of parameters is large. Other penalized regression methods have been proposed for group effect [6] - [13] . However, these methods either pre-suppose a grouping structure or assume that each predictor in a group shares an identical regression coefficient.

In practice, we often have some prior knowledge about the structure of variables and would like to make use of a priori information in analysis. For example, in gene analysis, we know the pathways and genes involved in these pathways. Therefore, we would like to group the involved variables in the same pathway together. Another example is in spatial analysis, we would like to keep a certain correlation structure among the spatial error terms. For example, sometimes we would like to fit a different coefficient for a certain variable at different regions (e.g., if the variable has different effect at different regions) but keep a correlation structure among the coefficients at neighborhood regions. The conditional autoregressive model (CAR, [14] ) is one of the methods that can be used to keep such correlation structure.

In this paper, we propose a method that encourages cluster variables to be selected together and can incorporate available prior information on coefficient structures in variable selection. When there is no prior information on coefficient structure, we propose a data augmentation algorithm to find the structure. Moreover, the method uses the Lasso regularization to choose sparse models. The proposed method can be solved by any efficient Lasso algorithm such as least angle regression (LARS, [15] ) and the coordinate-wise descent algorithm (CDA, [16] ). We call our method the Clustering Lasso (CL).

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we review the Lasso method and discuss its limitation in identifying clustered variables. Then we propose the Clustering Lasso in a Bayesian setting. Its counterparts in the Frequentist setting and computational strategies are discussed in Section 3. Sections 4 and 5 demonstrate the predictive and explanatory performance of CL through real examples and simulations. Finally, conclusions and future work are discussed in Section 6.

2. Clustering Lasso in Bayesian Setting

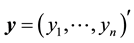

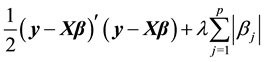

Consider linear regression settings with the response vector  and

and  dimensional input matrix

dimensional input matrix . The

. The  and columns of

and columns of  are centered and standardized to have the same

are centered and standardized to have the same  norm. The Lasso estimates

norm. The Lasso estimates  are calculated by minimizing

are calculated by minimizing

(1)

(1)

The solution of Lasso can be obtained through

Group effect has been defined by [1] in the linear regression setting. Let  be the

be the  th predictor. The estimates of coefficients have the group effect if

th predictor. The estimates of coefficients have the group effect if

and the penalty term,

In a Bayesian setting, if

In Lasso, the penalty term of model complexity is

For simplicity, assume that the variance of the random error,

Therefore, the posterior distribution of

with a vector

Relating Equation (4) to the Bayesian Lasso solution to (1), we naturally infer the Clustering Lasso in Frequentist setting.

3. Clustering Lasso

3.1. Clustering Lasso and Its Grouping Effect

In Frequentist setting, we modify the penalization function in Lasso to retain a presumed correlation structure among coefficients. Let

where

Figure 1 illustrates the Clustering Lasso penalty contours with two predictors. The right figure shows the penalty contour when the two predictors are correlated and the left one shows the contour when the two predictors are independent, which is identical to the Lasso method. The sums of the squared errors have elliptical contours, centered and minimized at the full least squares estimate. The constraint region of Lasso is the diamond region

constraint regions. The sides of the parallelogram are decided by the structural correlation matrix

Figure 1. Estimation picture for the Clustering Lasso when two predictors are independent (left, as lasso) and when two predictors are clustered (right).

3.2. Computation

The Clustering Lasso is an extension of the Lasso method. Let

Therefore, all the established algorithms for Lasso solution, such as the least angle regression (LARS, [15] ), could be used for Clustering Lasso.

3.3. The Clustering Lasso Algorithm

We can incorporate prior knowledge of clustering into a structural correlation matrix. For example, Kyoto Encyclopedia and

for

by the Lasso property, some

In detail, we develop Algorithm 1―the Clustering Lasso algorithm. Let

Algorithm 1 Clustering Lasso

1. For

for

do correlation test between

2. Do

3. Let

4. Do Lasso on

5.

Note that only when some elements of

3.4. Choice of Tuning Parameters

Four parameters,

The last parameter to be tuned is

4. Microarray Data Example

We used the proposed method on an Affymetrix gene expression dataset. The data were collected by Singh et al. [19] and consists of 12,600 genes, from 52 prostate cancer tumor samples and 50 normal prostate tissue samples. The goal is to construct a diagnostic rule based on the 12,600 gene expressions to predict the occurrence of prostate cancer. Support vector machine (SVM, [20] ), Ridge, Lasso, Elastic Net, Weighted Fusion (w.fusion) and Clustering Lasso were all applied to this dataset. We tried four types of Clustering Lasso methods:

1. CL1:

2. CL2:

3. CL3:

4. CL4:

To apply these methods, we first coded the presence of prostate cancer as a 0-1 (no and yes) response

The dataset was split 20 times. For each repetition, a 1000-gene set was preselected based on the training data to make the computation manageable. The genes are those “most significantly” related to the response, tested by individual t-statistics. Figure 2 shows the boxplots of the misclassification rates on the test data sets from different classifiers. The misclassification rates are summarized in Table 1. Overall, the misclassification rate from Clustering Lasso is competitive with Elastic Net and Ridge, and is better than Lasso, Weighted Fusion, and SVM. For the computational time, Clustering Lasso is comparable to the Lasso method and is much more efficient than Elastic Net and Weighted Fusion. Within the four Clustering Lasso methods, the ones with more restrictions on eigenvalues and the magnitudes of correlations perform a little bit worse.

Table 2 shows the average number of genes selected from the 20 repetitions based on different methods. The analyses were based on 1000 genes and 52 observations. We see that Lasso selected fewer than 52 genes. Elastic Net eliminated few genes―the average number of selected genes was close to 1000. Cluster Lasso identified about 25% genes as important. However, we do not know whether the chosen genes are, in fact, important or not. The efficiency of variable selection is further assessed by simulation studies.

Figure 2. Misclassification rates on singh data. ELAS stands for Elastic Net.

Table 1. Summary of Misclassification Rates on Singh data.

Table 2. Average number of genes selected by each method.

5. Simulation Studies

We applied Clustering Lasso on some simulations to test its prediction accuracy in regressions when compared with Ridge, Lasso, Elastic Net, and Weighted Fusion. The first three simulations are adapted from the Elastic Net paper [1] . To begin, datasets are simulated from the true model:

For each scenario, we simulated 100 data sets, each consisting of a training data set and an independent test data set. Here are the details of the four scenarios.

1. In example one, we simulated

was set to be

2. In Example two, we simulated 200 training data and 400 testing data. There are 40 predictors such that

3. Example 3 has the group setting that

As explained by [1] , three groups are equally important groups, and each group contains five covariates. We created

The fourth simulation is a modification of the third example to emphasize the group effects. The true model has the form

The latent variables,

We used all four Clustering Lasso methods. In all examples, the results from the four Clustering Lasso methods are close to each other. The prediction results from Lasso, CL2, CL4, Elastic Net, Ridge, and Weighted Fusion are summarized in Table 3 and Figure 3. In Figure 3, relative MSE was defined as the MSE of the corresponding method divided by the minimum MSEs from all the methods. We see that Clustering Lasso always performs better than the Lasso method, and it is close to or better than Ridge, Weighted Fusion and Elastic Nets, even under collinearity and group effect situations.

Table 4 shows the results of variable selection. The two numbers in each cell are the proportion of times an important factor is chosen and the proportion of times a false factor is chosen, respectively. We see that compared with Elastic Net, Weighted Fusion and Lasso, Clustering Lasso is superior at selecting important factors. However, like Weighted Fusion, it is more likely to over select variables than Elastic Net. In Example 2,

Figure 3. Comparing the simulation results from the four examples. (a)-(d): Example 1-4.

Table 3. Mean (standard deviation) of MSE for the simulated examples based on the 100 iterations.

Table 4. Variable selection results for the simulated examples based on the 100 iterations. In each cell, the first number is the proportion of times a true factor is chosen and the second number is the proportion of times a false factor is chosen.

since all variables are highly correlated, Clustering Lasso cannot identify the most important variables. In comparison, Clustering Lasso performs very well in Examples 3 and 4, when clusters of variables play an important role in real model.

Finally, to show how Clustering Lasso chooses covariates in groups and the behavior of the coefficients for the selected variables, we illustrate the differences between Lasso and Clustering Lasso by a modified example from [1] . Let

response variable is generated as

observed predictors are

The variables

We also use this simulation to compare the sensitivity and specificity of the listed methods in finding significant covariates. The simulation is repeated 100 times. Table 5 summarizes the number of times that the coefficients of

Figure 4. Comparing the solution paths from Lasso, Elastic Net and Clustering Lasso.

Table 5. Number of times the coefficients are not zero based on the 100 repetitions.

6. Conclusions and Future Works

We find that the Clustering Lasso, is a novel predictive model that produces sparse model with good predictive performance, while encouraging group effects. The empirical results from a two-class microarray data classifica- tion problem and several simulation studies on regression problems show that Clustering Lasso has very good predictive performance and is superior to the Lasso method.

The method was proposed to encourage group effects so that clustered variables are selected together in a model. Clustering Lasso can automatically select groups of variables. If the structural correlation matrix used for regularization is block diagonal matrix, Clustering Lasso is equivalent to the group Lasso proposed by [7] . However, if the relationships among the variables are complicated, we have to simplify the structural correlation matrix to obtain sparse models. We proposed some shrinkage steps to build the desired structural correlation matrix. Rotating the

Acknowledgements

We thank

References

- Hoerl, A.E. and Kennard, R.W. (1970) Ridge Regression: Application to Nonorthogonal Problems. Technometrics, 12, 69-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00401706.1970.10488635

- Tibshirani, R. (1996) Regression Shrinkage and Selection via the Lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 58, 267-288.

- Zou, H. and Hastie, T. (2005) Regularization and Variable Selection via the Elastic Net. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 67, 301-320. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9868.2005.00503.x

- Alter, O., Brown, P. and Botstein, D. (2000) Singular Value Decomposition for Genome-Wide Expression Data Pro- cessing and Modeling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 97, 10101- 10106.

- Zou, H., Hastie, T. and Tibshirani, R. (2006) Sparse Principal Component Analysis. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 15, 265-286. http://dx.doi.org/10.1198/106186006X113430

- Tibshirani, R., Saunders, M., Rosset, S., Zhu, J. and Knight, K. (2005) Sparsity and Smoothness via the Fused Lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 67, 91-108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9868.2005.00490.x

- Yuan, M. and Lin, Y. (2006) Model Selection and Estimation in Regression with Grouped Variables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 68, 49-67. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9868.2005.00532.x

- Bondell, H.D. and Reich, B.J. (2008) Simultaneous Regression Shrinkage, Variable Selection, and Supervised Clustering of Predictors with OSCAR. Biometrics, 64, 115-123. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00843.x

- Daye, Z.J. and Jeng, X.J. (2009) Shrinkage and Model Selection with Correlated Variables via Weighted Fusion. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 53, 1284-1298. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.csda.2008.11.007

- Jenatton, R., Obozinski, G. and Bach, F. (2010) Structured Sparse Principal Component Analysis. International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS).

- Jenatton, R., Audibert, J.Y. and Bach, F. (2011) Structured Variable Selection with Sparsity-Inducing Norms. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 12, 2777-2824.

- Huang, J., Ma, S. and Zhang, C.H. (2011) The Sparse Laplacian Shrinkage Estimator for High-Dimensional Regression. Annals of Statistics, 39, 2021-2046. http://dx.doi.org/10.1214/11-AOS897

- Buhlmann, P., Rutimann, P., van de Geer, S. and Zhang, C.H. (2013) Correlated Variables in Regression: Clustering and Sparse Estimation. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference, 143, 1835-1858. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jspi.2013.05.019

- Besag, J. (1974) Spatial Interaction and the Statistical Analysis of Lattice Systems (with Discussion). Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B, 36, 192-236.

- Efron, B., Johnstone, I., Hastie, T. and Tibshirani, R. (2004) Least Angel Regression. Annals of Statistics, 32, 407-499. http://dx.doi.org/10.1214/009053604000000067

- Friedman, J., Hastie, T., Hofling, H. and Tibshirani, R. (2007) Pathwise Coordinate Optimization. Annals of Applied Statistics, 1, 302-332. http://dx.doi.org/10.1214/07-AOAS131

- Schafer, J. and Strimmer, K. (2005) A Shrinkage Approach to Large-Scale Covariance Estimation and Implications for Functional Genomics. Statistical Applications in Genetics and Molecular Biology, 4, 32.

- Jolliffe, I.T., Trendafilov, N.T. and Uddin, M. (2003) A Modified Principal Component Technique Based on the Lasso. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 12, 531-547. http://dx.doi.org/10.1198/1061860032148

- Singh, D., Febbo, P., Ross, K., Jackson, D.G., Manola, J., Ladd, C., Tamaryo, P., Renshaw, A.A., D’Amico, A.V., Richie, J.P., Lander, E.S., Loda, M., Kantoff, P.W., Golub, T.R. and Sellers, W.R. (2002) Gene Expression Correlates of Clinical Prostate Cancer Behavior. Cancer Cell, 1, 203-209. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1535-6108(02)00030-2

- Guyon, I., Weston, J., Barnhill, S. and Vaapnik, V. (2002) Gene Selection for Cancer Classification Using Support Vector Machines. Machine Learning, 46, 389-422. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1012487302797