Advances in Sexual Medicine

Vol.2 No.3(2012), Article ID:21351,9 pages DOI:10.4236/asm.2012.23007

Swedish Women’s Emotional Experience of the First Trimester in a New Pregnancy after One or More Miscarriages: A Qualitative Interview Study

School of Life Sciences, University of Skovde, Skovde, Sweden

Email: annsofie.adolfsson@his.se

Received May 22, 2012; revised June 25, 2012; accepted July 5, 2012

Keywords: Miscarriage; Pregnancy after Miscarriage; Subsequent Pregnancy; Women’s Emotional Experiences; Worry

ABSTRACT

Objectives: The aim of this study was to evaluate how Swedish women describe their emotional state of being during the eighth week through the eleventh week after they have become pregnant again after suffering a previous miscarriage. Method: A qualitative content analysis with an inductive approach has been used to analyze fourteen interviews that served as the data base for this study. The content analysis resulted in the development of five categories which evolved into one primary theme. Findings: The five categories identified were Worry and preoccupation; Distance; managing their feelings; Mourning what is lost; Guarded happiness and expectations. These categories were compiled into a main theme, “Worry consumes a lot of energy, but on the other side lies happiness”. This theme focused on whether the women could feel any happiness about being pregnant again despite their concerns with the previous miscarriage. Conclusions: The emotional states of the women when they get pregnant again are typically characterized by anxiety, worry and concerns about their current pregnancy. The women have a tendency to distance themselves emotionally from their pregnancy but also strive to find the joy of being pregnant again. During the new pregnancy they find themselves in need of support from their family and friends as well as in need of support from the healthcare system.

1. Introduction

Becoming pregnant is a life changing event for expectant parents, as their perspective of life goes through a radical change and they suddenly feel they are headed in an entirely new direction. A percentage of these pregnancies will unfortunately terminate in miscarriage [1] and these women may become pregnant again [2] while carrying with them their misgivings of their earlier loss [3,4]. The percentage of miscarriages from a Scandinavian study is approximately 15% - 20% of all pregnancies [5,6] and in Sweden one in every four women who give birth state that they have experienced one or more miscarriages [2]. Miscarriage is defined as the spontaneous loss of a fetus weighing less than 500 grams. Early miscarriage describes an event that occurs before the end of twelfth week of the pregnancy and a late miscarriage occurs between the thirteenth and twenty-second week of a pregnancy. The term stillborn is used when the fetus is born with no evidence of life after 22 full weeks of gestation [7].

The physiological and psychological changes that occur in pregnant women during the early stages of their pregnancy can lead to emotional sensitivity, an increase in anxiety and even emotional instability in some women [8]. Pregnant women have plenty of concerns to choose from as they include concerns about their own health, the health of their unborn baby, the future delivery and they are also concerned about what life will be like after the delivery [9]. Whether or not the pregnancy was planned, most women have a sense of ambivalence towards the fetus, where the immediate concerns about protecting the unborn child are mixed with the sometimes overwhelming concerns about the changes in their life that are on the horizon [10].

Generally speaking, pregnant women may go through three distinctly separate phases in their pregnancies which can be classified as the fusion of mother and fetus, the differentiation of mother and fetus and finally the separation phase. The initial fusion phase is when the women accept the fact and the responsibility that they are carrying another life within their womb. Differentiation occurs when she feels movement of the fetus which enables her to grasp the concept that the life is something other than her own. Finally, the fetus is mature enough to survive birth and the women prepare themselves for delivery [11].

Approximately sixty percent of the women who have experienced a miscarriage become pregnant again within a year [12] and almost ninety percent of the women who desire to become pregnant after a miscarriage have managed to do so within two years [13]. Becoming pregnant again after the experience of perinatal loss is worrisome for the expectant mothers and the aim of this study was to evaluate how Swedish women describe their emotional state of being during the eighth week through the eleventh week after they have become pregnant again.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

In this qualitative interview study, a content analysis with an inductive approach was used to describe the emotional experience of women who have become pregnant again after suffering one or more miscarriages. The qualitative content analysis strives to obtain knowledge, information and understanding within the research objectives while focusing on the human communication of the experience. By identifying the differences and the similarities within the contents of the interviews, variations of the experience can be evaluated. An inductive approach draws upon the human experience but consists of an unbiased analysis of the text. From this perspective an attempt is made to discover new insights.

One variation of this method is to focus on those things that are overtly expressed in the interview transcripts which is the manifest content. Another option is to analyze the latent content which interprets the underlying meaning of the text [14]. The authors of this study have chosen to analyze the manifest content and the latent content in order to gain a deeper understanding of the women’s issues. Additional emphasis has been given to the latent content. The use of the inductive approach is preferable when describing the individuals personal experience of an event [14].

2.2. Selection of Participants

Participants in this study were women who had successfully become pregnant again between the years 2004 and 2007 after having suffered one or more miscarriages. The participants had previously participated in another study about structured appointments following a miscarriage [15] and they were asked during the process of that study if they would be interested participating in a subsequent study should they become pregnant again. Women who desired to participate in this study that had heard about it from other participants were included via the snowball process [16]. Inclusion criteria included that the participants must be Swedish speaking women, 18 years of age or older, who had at least one miscarriage and were currently pregnant again between their eighth and eleventh weeks into their pregnancy.

Women received verbal and written information about the purpose of the study, the interview process, confidentiality and the meaning of informed consent [17]. As a part of the agreement to participating in the study the interviewees were offered an ultrasound examination to confirm the status of their pregnancy. Sixteen women agreed to participate in the study. Of these, one interview was excluded due to a technical incident that destroyed the tape and another was eliminated when the potential participant was not able to keep her appointment.

2.3. Data Collection

The interviews of the fourteen participants were conducted in the office of the author at a hospital. The author interviewer, who is a registered midwife, described to each interviewee the purpose of the study in order to provide a background for the interview. The interviewer then asked the women about their emotional state during their current pregnancy after having previously suffered a miscarriage. The author interviewer asked questions of the participants to get additional information that was relevant to their emotional state during their current pregnancy.

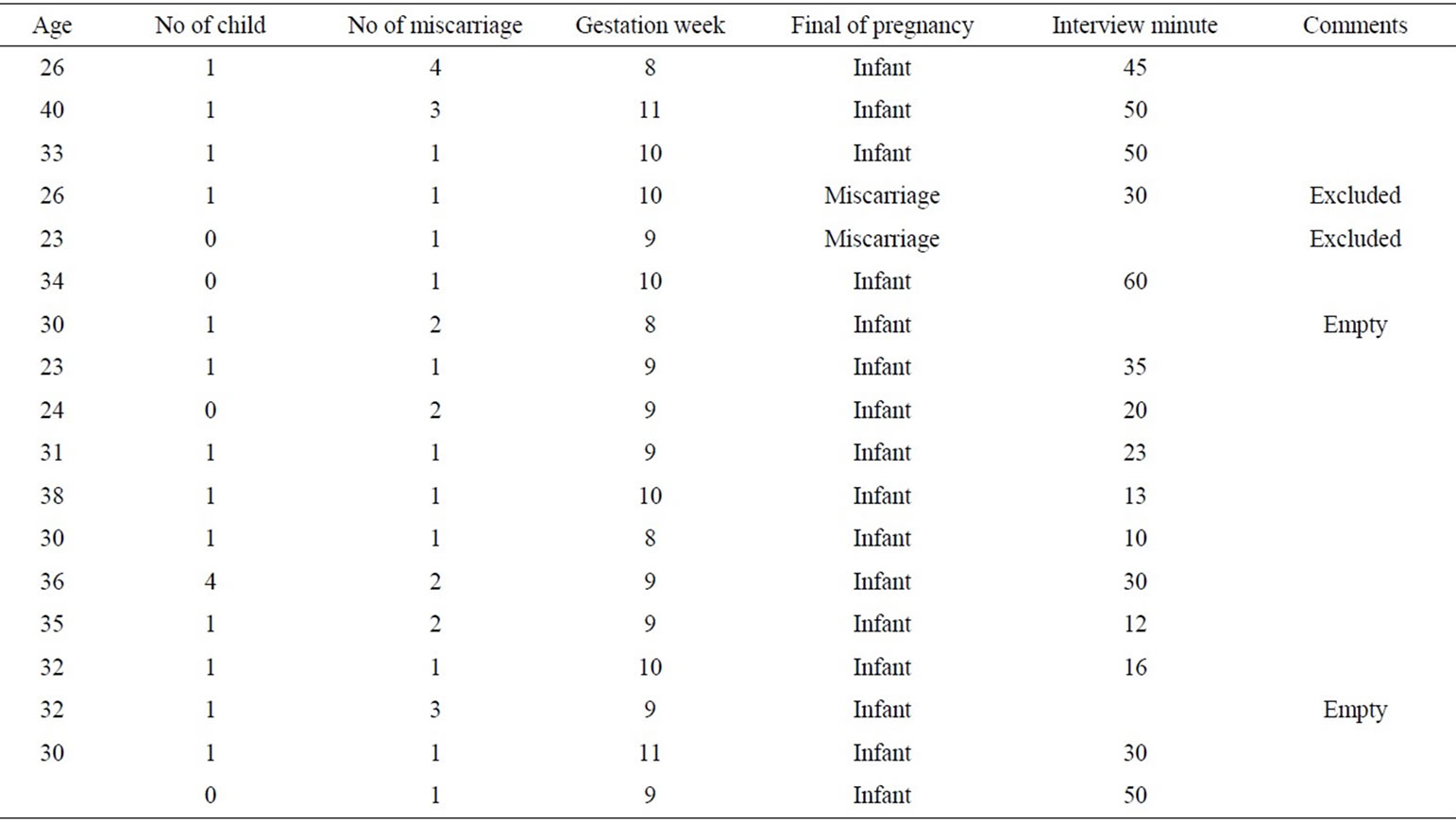

Before terminating the interview, the author asked the women if there was anything they would like to ask or if they had any further questions. The interviews were taperecorded which enabled the interviewer to focus on each individual woman and the dynamics of each specific interview [17]. The interviews lasted between 12 and 60 minutes each with the average length being 31 minutes (see Table 1).

2.4. Content Analysis

A total of fourteen women participated in the study and were interviewed accordingly. Some of these women had experienced successful childbirth, some had experienced a single miscarriage and some of them had experienced multiple miscarriages. The interviews were transcribed verbatim in order to retain the reality of the women’s emotional experiences and the transcriptions were performed by a secretary who was proficient in transcribing interviews [17]. The authors of the study individually listened to the taped interviews and read the transcripts several times in order to obtain further understanding of the respondents’ statements. Each author did their own analysis independently of each other.

Meaning bearing units were identified in each of the interviews and these were further condensed in order to eliminate data that was considered unimportant or irrelevant to the aim and objectives of the study. The con-

Table 1. Background data of the informants and length of interviews.

densed meaning bearing units were coded and categorized. Subcategories with similar content were combined together to form a total of five categories. After the interviews were analyzed separately, the authors combined their findings together by comparing and discussing each step of the process of their individual analyses until an agreement was reached about the meaning bearing units, the condensation, the coding and the categorizing.

Then by comparing and combining their findings, the authors felt a higher degree of reliability was obtained from their collaborative efforts. They then used the resulting combined effort and the resulting categories to identify the underlying meaning of the interview or the latent content into a theme (see Table 2) [14]. By creating a theme, the manifest content of the categories was tied together. This theme is seen as “the red thread” that can be followed through each of the categories as an expression of the latent content of the texts [14,16].

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The authors with their collaborative effort have endeavored to provide as accurate a picture as possible of the research subject while maintaining the confidentiality of their participants, as neither the hospital nor the participants can be identified from this article. The authors did not know the identities of the interviewees, who have remained anonymous. The interviewees were informed that the interviews and all materials belonging to the study would be kept confidential. All of the participants gave their written consent to participate in the study. Approval for the study was given by the ethics committee at the University of Gothenburg [18].

3. Findings

The women’s feelings about their new pregnancy after experiencing a previous miscarriage were developed into the theme of the study. The study demonstrated that the concerns are worrisome and energy consuming to the women’s emotional state but happiness can and does prevail as the mothers are happy to be pregnant again. The theme is derived from the five categories that were identified in the data analysis from the interviews: Worry and preoccupation; Distance; Managing their feelings; Mourning what is lost; Guarded happiness and expectations.

3.1. Worry and Preoccupation

Worry tended to dominate the women’s emotional state during the period between the eighth and eleventh weeks of their pregnancy that was the object of this study. This was distressing to the women. The fears of having another miscarriage were never far from their conscious thoughts during this period. Sometimes their concerns were interpreted as a double message in that they said that they were not worried about another miscarriage but at the same time they thought about the risks every day. Each passing day brought a sense of relief that brought them one day closer to the delivery date.

The women made it clear that they were not preoccu-

Table 2. Example of analysis. Interview and line numbers. Meaning units from different interview units are exemplified using examples of condensing units, codes, subcategories, and the five categories. This is concluded with the theme that emerged from all the units of analysis.

pied with worries of miscarriage before they had one. When they became pregnant after a miscarriage, they had a different perspective and they were afraid of a repeat occurrence and their attitudes were a bit fatalistic about the prospects. They felt that if a miscarriage was to occur again, it would be just as well if it occurred early on in the pregnancy so that they could be released from the worry and the distress of the fears that something could go wrong. Women with living children said that if something were to go wrong with their current pregnancy their fears of another miscarriage would have an impact on their decision to attempt to have another child.

The existence of normal pregnancy symptoms such as nausea and swollen breasts were reassuring to the women because these were signs of a viable pregnancy. The presence of symptoms did not completely dispel their fears and some of the women felt that they lacked the ability to discern the signs of a viable pregnancy. The lack of perceptible symptoms made the women particularly anxious. Women that had delivered children successfully in the past had the advantage of having a positive experience to compare their present situation to. Generally speaking, the women were alert to their pregnancy symptoms and at the same time vigilant for any negative signs that they were familiar with from their previous experience of miscarriage.

Every time you go to the bathroom you take notice so that there is no blood. You go a few extra times just to check, it’s very psychological. You sit and feel for it the whole time (Interview 14).

Other causes for concern and preoccupation were perhaps things like their ingesting alcohol before they were confirmed as pregnant. They worried about the food that they were eating and they worried about the effect that any stress that they experienced might have on their fetus. The women were worried about causing another miscarriage or causing injury to the fetus as a result of their own behavior. The number of gestation weeks was an important milestone for the participants. Each passing week was a sign of a viable pregnancy and a healthy fetus. The women anticipated relief from their worries when they passed the twelfth week of their pregnancy.

The whole time it’s in the back of your mind that something might go wrong. You try not to expect too much…so I haven’t thought much past the twelfth week. If I can just get past that week, I think everything will feel ok. Let’s hope so (Interview 14).

They eliminated risks that might affect the pregnancy. The women postponed operations, they endured pain without taking unnecessary medication and they avoided everything that could possibly constitute a risk for the fetus.

3.2. Distance

When women have become pregnant again after experiencing a miscarriage, it can be difficult to accept the fact that they have conceived. In some respects the women were distancing themselves from the reality of the situation because of their previous unpleasant experience with their miscarriage. These women were optimistic that everything was going to be alright but were hesitant to give in to a real sense of joy because of their residual misgivings. They did not want to get their hopes up only to be disappointed again. Even though their bodies evidenced all of the signs of a normal pregnancy, psychologically they prepared for another potential mishap should the pregnancy end in a miscarriage. They attempted to not think about the future or to not plan too far in advance, which meant that they could not dare to enjoy their current pregnancy to its fullest potential due to their emotional state.

I don’t really think about the fact that I have a baby in my womb, in the way that I did before the miscarriage…and I don’t prepare for it in the same way either. I don’t at any rate (Interview 7).

The women had ambivalent feelings about their new pregnancy after the previous experience of a miscarriage. They were caught between the hopes and dreams of delivering a child and from distancing themselves from their pregnancy in the event that something should go wrong again. They were not entirely capable of eliminating the possible negative outcomes because of their fears and misgivings.

3.3. Managing Their Feelings

The women struggled to manage their combined feelings and emotions about their new pregnancy and of the previous miscarriage. They needed concrete and straightforward answers from the healthcare professionals regarding both conditions, about the current pregnancy and about the prior miscarriage. If they were able to get the information they felt that they needed, it made it easier for them to manage their feelings and any misgivings they might have. When the women became pregnant again following a miscarriage an early extra visit to the midwife was perceived as something beneficial and the meeting helped them to process their feeling about the miscarriage. Comprehensive information and adequate answers regarding their pregnancy ranging from symptoms and diet gave the women a sense of control and stability. This gave them a more positive feeling and therefore a more positive attitude going forward and this made it easier for them to experience their pregnancy and eventually deliver their baby.

The women felt it was important to have the sympathy and understanding of their family and friends. When they were able to share their new pregnancy with their family and friends it made it easier on them because it eliminated a feeling of isolation. They felt that if they should miscarry again that they would probably share their loss with this intimate circle of family and friends instead of isolating themselves. Interviewees that had friends who had also experienced a miscarriage received additional support from these women who could more naturally sympathize with their sense of loss and disappointment.

In this respect it was quite comforting to have someone who had experienced the same worries that I did and had known those same misgivings. We can talk to each other and are able to sympathize with each other’s feelings. It was great to have someone to share with (Interview 7).

The women felt the need to establish a sense of control in their pregnant conditions. They took multiple pregnancy tests to try and establish this feeling of control by continuously confirming the viability of their condition. They saw the ultrasound examination as a way of confirming their pregnancy and this gave them peace of mind. On the other hand, the examination had the effect of making them nervous because it was an ultrasound exam that had confirmed the miscarriage that they had suffered previously. They wanted to get the exam over with so that they could go forward with their pregnancies and this helped them to sleep better at night.

3.4. Mourning What Is Lost

The current pregnancy provoked thoughts and feelings about the previous experience of their miscarriage. The women felt that they needed the support of their family and friends but they sometimes did not feel they got the support they needed. Having other children did not necessarily prevent them from mourning the potential child that they had lost and they perceived comments from their intimate circle of family and friends to sometimes be insensitive and trivializing to their experience.

They sometimes felt regret if they did not get the chance to fully process the sense of loss that the miscarriage created in them. The miscarriage had a tendency to evoke old and dormant feelings from earlier events in life and the new pregnancy would give them a new immediacy. Childhood memories and remembrances of deceased relatives sometimes surfaced, which had the effect of making the women feel more sensitive and vulnerable in their pregnancy.

The women expressed that they would always carry with them the memory of the miscarriage experience and mourn the potential child that they had lost. Even though the sense of immediate grief would dissipate, the memory of the loss and the subsequent pain would always be there.

But the residual feelings from the experience are still there…and I am unable to forget it (Interview 4).

The women realized that they needed and desired the professional support that the healthcare system could provide in their new pregnancy. When they did not get the support that they felt they needed from the midwife, for instance, if she did not listen carefully and provide the empathy required of the women, the women felt abandoned by the system. This created some problems with their relationship with the midwife which had the effect of further isolating the women with their own problems. The women had expectations of the midwives and they were disappointed if they did not feel they were being taken as seriously as they felt they needed to be.

After the text edit has been completed, the paper is ready for the template. Duplicate the template file by using the Save As command, and use the naming convention prescribed by your journal for the name of your paper. In this newly created file, highlight all of the contents and import your prepared text file. You are now ready to style your paper.

3.5. Guarded and Expectations

For most of the participants their new pregnancy was planned and anticipated. The women were definitely pleased to be pregnant again but the happiness they felt had a cautious feeling to it. They felt a careful and yet budding joy. At times they would let themselves plan ahead and feel the normal expectations about their anticipation of having a child. Positive reactions and feedback from the significant people in their intimate circle had the effect of making the women more secure which in turn helped them to feel happy. It helped them to confirm that their pregnancy was viable and the expectations that went with it were realistic.

After the pregnancy was confirmed by the ultrasound examination the women expressed a profound sense of relief and it gave them a belief in the viability of the pregnancy. They felt an increased sense of confidence that everything was going to work out well in the end. The exam gave the women the courage to circumvent the fears and anxiety that they had been experiencing and it gave them the courage to tell others about their pregnant condition.

After the ultrasound exam the women felt that they could let their guard down a bit and they could trust the signals that their bodies gave them. By listening to those signals it gave them positive feedback that everything was alright with their pregnancy.

We both feel that every day I feel sick is actually a good day. To feel morning sickness is a good sign, and that makes me feel good (Interview 13).

The confirmation of the ultrasound exam allowed the women to reengage with their lives which included engaging in their fitness workouts and the other routines that made them feel good in the past. At the same time the women also started to carefully prepare for their new lives as parents. They understood that the preparation for parenthood took time and they were glad that they had that time to make the necessary preparations. They were now able to anticipate and adjust to the prospect of parenthood and they adapted their lifestyles to welcome a small baby into their homes. They had a new perspective on life and were excited about it. While the women could not forget the past, they dared to look forward again and to manage the future possibilities for their family.

3.6. Worry a Lot of Energy

The analysis of the interviews reveals that the women have many concerns and worries to resolve during the study period between the seventh and twelfth weeks of pregnancy after becoming pregnant again following the unfortunate experience of miscarriage. The analysis also reveals that happiness in their pregnant state is possible once they have resolved these concerns, often with the help of a corroborating ultrasound examination.

Their anxieties had a definite influence on their moods and emotions which made it difficult to have a positive attitude about their pregnant condition and to believe in their ability to trust their bodies. When the obvious signs of a viable pregnancy appeared, such as the nausea and the fatigue, the trust in their bodies was rediscovered and they were more capable of feeling the happiness associated with the expectation of a new baby in the future. From these findings of this analysis we found the emerging theme, “Worry consumes a lot of energy, but on the other side lies happiness”.

4. Discussion

The main findings in this study about the emotional state of Swedish women, who become pregnant again after one or more miscarriages, corroborate the findings of other studies that have found that the women had a tendency to become excessively worried about their pregnancies [19,20]. The study also demonstrated that these women were capable of feeling cautious optimism and happiness if they managed to resolve their immediate concerns. Interviewees with previous successful deliveries of babies found it easier to cope with the anxiety because they could compare the signs and the symptoms of their current pregnancy with previous pregnancies that resulted in their live births. These findings are consistent with the study of Woods-Giscombé et al. [21].

The findings of this study reveal that women who have suffered miscarriage in the past want to be content in their pregnancies and leave their worries behind once they have progressed beyond the point in their gestation where their miscarriages had occurred. According to the current study, the worrying motivated the women to watch for signs that the pregnancy was viable and they found it difficult to stop looking for the signs of another miscarriage. The study of Côté and Arsenault reveals that the vigilance of the women continuing to look for the signs that they missed during their previous miscarriage, is an indication that they felt that they could have prevented their previous miscarriage if they had been more observant [19].

In this study, the women found that the extra ultrasound examination offered to them with their participation in this study was highly beneficial to them. When their pregnancy was confirmed to be viable by the early ultrasound examination at the time of their interview they felt that they could relax with some of their anxiety. They felt that they could afford to feel more confident about the future. There are several studies that have described that the emotional states of these women continue to remain somewhat fragile with persisting anxiety throughout the new pregnancy, even in the later stages, when compared with women who have not suffered perinatal loss before [3,21,22,24].

The women in this study found that their emotional states fluctuated between their insecurities and their desire to be content with the new pregnancy. The urgency of their concerns seemed to correlate with their current gestational period and with the point where they suffered the previous miscarriage. The women were cautious about feeling optimistic and this made them cautious to express their optimism, which had the effect of distancing themselves from their pregnancies. This distancing effect from the reality of their pregnancy is more than likely a defense mechanism that they employ to protect themselves in the event of another miscarriage. There is substantiating evidence to back up the theory that women who have suffered a miscarriage tend to distance themselves in future pregnancies when compared to women who have not suffered a perinatal loss before [20].

Women that become pregnant again after experiencing a previous miscarriage are more often to find themselves in need of professional support and this was supported by the interviewees of this study. They were in need of support in terms of access to information and answers to their questions. Much of this support is provided by the healthcare provider which demonstrates how important it is to have a positive, supporting and trusting relationship with the healthcare system. It was vital for these women to meet with the midwife early on in their pregnancies and to continue to meet with them on a regular basis, which was more than the standard care of the antenatal department typically provided. Once again the study of Côté-Arsenault supported the need for more healthcare visits [22]. The women also stated how important it was for them to receive support from the healthcare system in order that they could resolve the issues of their previous loss [23]. Additional or enhanced support from the healthcare system was perceived to be very beneficial to the women of this study.

Conclusions

The emotional state of women who become pregnant again after experiencing a previous miscarriage is often characterized by a number of conflicting tendencies to indulge in excessive worrying and the desire to feel optimistic about the future outcome of the pregnancy. Even though women may distance themselves from the reality of their pregnancy out of a defense mechanism behavior, they still are keen to experience the joy and happiness of child-bearing. Midwives should be aware of each individual woman’s obstetric history and give them the necessary support based on their individual needs. It is very important for the women to feel that their feelings are respected and that their concerns are taken seriously. The loss that they have experienced with a previous miscarriage is substantial and often they need professional support, in addition to their social network, to resolve their concerns.

Additional studies in the areas of support for women who have become pregnant again after experiencing a miscarriage are needed to provide a larger basis of information in order to provide a larger and more comprehensive understanding of the needs of these women.

5. Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all of the women who participated in the study and shared their emotional experience of becoming pregnant after suffering a miscarriage. Their contributions will be helpful to women in the future who experience a similar loss. The study was supported by grants from the research and development unit, Skaraborg Hospital, Skövde.

6. Authors Contribution

The authors are grateful to all of the women who participated in the study and shared their emotional experience of becoming pregnant after suffering a miscarriage. Their contributions will be helpful to women in the future who experience a similar loss. The study was supported by grants from the research and development unit, Skaraborg Hospital, Skovde.

REFERENCES

- A. Adolfsson, P. G. Larsson, B. Wijma and C. Berterö, “Guilt and Emptiness: Women’s Experiences of Miscarriage,” Health Care for Women International, Vol. 25, No. 6, 2004, pp. 543-560. doi:10.1080/07399330490444821

- A. Adolfsson and P. G. Larsson, “Cumulative Incidence of Previous Spontaneous Abortion, In: Sweden 1983- 2003: A Register Study,” Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, Vol. 85, No. 6, 2006, pp. 741-747. doi:10.1080/00016340600627022

- D. Côté-Arsenault, “Threat Appraisal, Coping, and Emotions across Pregnancy Subsequent to Perinatal Loss,” Nursing Research, Vo. 56, No. 2, 2007, pp. 108-111. doi:10.1097/01.NNR.0000263970.08878.87

- M. Whitworth, L. Bricke, J. P. Neilson and T. Dowswell, “Ultrasound for Fetal Assessment in Early Pregnancy,” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Vol. 14, No. 4, 2010. http://onlinelibrry.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD007058/frame.html

- A. M. N. Andersen, J. Wohlfarth, P. Christens, J. Olsen and M. Melbye, “Maternal Age and Fetal Loss: Population Based Register Linkage Study,” British Medical Journal, Vol. 320, No. 7251, 2000, pp. 1708-1712. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7251.1708

- E. Hemminki and E. Forssas, “Epidemiology of Miscarriage and Its Relation to Other Reproductive Events in Finland,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 181, No. 2, 1999, pp. 396-401. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70568-5

- Modifications Recommended by FIGO as Amended October 14, “WHO: Recommended Definitions, Terminology and Format for Statistical Tables Related to the Perinatal Period and Use of a New Certificate for Cause of Perinatal Deaths,” Acta Obstetricia Gynecologica Scandinavica, Vol. 56, No. 3, 1977, pp. 247-253.

- J. G. Bruhn, “The Two Sides of Worry,” Southern Medical Journal, Vol. 83, No. 5, 1990, pp. 557-562. doi:10.1097/00007611-199005000-00020

- T. Bondas and K. Eriksson, “Women’s Lived Experiences of Pregnancy: A Tapestry of Joy and Suffering,” Qualitative Health Research, Vol. 11, No. 6, 2001, pp. 824-840. doi:10.1177/104973201129119415

- B. Wickberg, “Psychological Instance during Pregnancy and the Time Postpartum—A Method to Maternity Health Care. [Psykologiska Insatser under Graviditet och Postpartumtid—En Metod för Mödrahälsovården], In: B. Sjögren, Ed., Psykosocial Obstetrik, Body, Soul and Childbearing, Studentlitteratur, Lund, 2005, pp. 71-88.

- H. Rowe, “Spontaneous Pregnancy Loss,” Mental Health Aspects of Women’s Reproductive Health: A Global Review of the Literature, World Health Organization, 2009. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241563567_eng.pdf

- K. M. Swanson, S. Connor, S. N. Jolley, M. Pettinato and T. J. Wang, “Context and Evolution of Women’s Responses to Miscarriage during the First Year after Loss,” Research in Nursing and Health, Vol. 30, No. 1, 2007, pp. 2-16. doi:10.1002/nur.20175

- F. Blohm, M. Hahlin, S. Nielsen and M. Milsom, “Fertility after a Randomized Trial of Spontaneous Abortion Managed by Surgical Evacuation or Expectant Treatment,” The Lancet, Vol. 349, No. 9057, 1997, p. 995. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)24014-6

- U. H. Graneheim and B. Lundman, “Qualitative Content Analysis in Nursing Research: Concepts, Procedures and Measures to Achieve Trustworthiness,” Nurse Education Today, Vol. 24, No. 2, 2004, pp. 105-112. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

- A. Adolfsson, C. Berterö and P. G. Larsson, “Effect of a Structured Follow-Up Visit to a Midwife on Women with Early Miscarriage: A Randomized Study,” Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, Vol. 85, No. 3, 2006, pp. 330-335. doi:10.1080/00016340500539376

- D. F. Polit and C. T. Beck, “Nursing Research: Principles and Methods,” 7th Edition, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2004.

- S. Kvale and S. Brinkmann, “Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing,” Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, 2009.

- “CODEX—Rules and Guidelines for Research,” 2012. http://www.codex.vr.se/en/index.shtml

- D. Côté-Arsenault, K. Donato and S. Sullivan, “Watching and Worrying: Early Pregnancy after Loss Experiences,” MCN: The American Journal of Maternal and Child Nursing, Vol. 31, No. 6, 2006, pp. 356-363.

- D. Armstong and M. Hutti, “Pregnancy after Perinatal Loss: The Relationship between Anxiety and Prenatal Attachment,” Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing, Vol. 27, No. 2, 1998, pp. 183-189. doi:10.1111/j.1552-6909.1998.tb02609.x

- C. Woods-Giscombé, M. Lobel and J. Crandell, “The Impact of Miscarriage and Parity on Patterns of Maternal Distress in Pregnancy,” Research in Nursing and Health, Vol. 33, No. 4, 2010, pp. 316-328. doi:10.1002/nur.20389

- D. Côté-Arsenault, “The Influence of Perinatal Loss on Anxiety in Multigravidas,” Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing, Vol. 32. No. 5, 2003, pp. 623-629. doi:10.1177/0884217503257140

- D. Armstrong, “Impact of Prior Perinatal Loss on Subsequent Pregnancies,” Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing, Vol. 33, No. 6, 2004, pp. 765-773. doi:10.1177/0884217504270714

- M. Johnson and E. Tsartsara, “The Impact of Miscarriage on Women’s Pregnancy-Specific Anxiety and Feelings of Prenatal Maternal-Fetal Attachment during the Course of a Subsequent Pregnancy: An Exploratory Follow-Up Study,” Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 27. No. 3, 2006, pp. 173-182.