Current Urban Studies

Vol.05 No.02(2017), Article ID:76737,18 pages

10.4236/cus.2017.52009

Regional Development Planning in Istanbul: Recent Issues and Challenges

Nevra Gursoy1, David J. Edelman2

1Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Istanbul Technical University, Istanbul, Turkey

2School of Planning, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA

Copyright © 2017 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: May 4, 2017; Accepted: June 4, 2017; Published: June 7, 2017

ABSTRACT

As a response to contemporary globalization and urbanization issues, the regional approach has become part of development policies in many countries. In addition, regional planning is seen as a supportive tool for regional development policies. While countries notice “the need for regional planning” more and more, they provide strong support to improve it. There is an increasing interest in regional planning in Turkey as well as other countries. This interest is reflected in administrative and institutional changes, as well as changes in planning legislation. However, there are still complications and deficiencies regarding regional planning. This article aims to present current developments in regional planning in Turkey and draw a general picture of its challenges within the existing planning system. Istanbul, as the most important metropolitan area in Turkey, provides fruitful insights in drawing conclusions for the study.

Keywords:

Regional Planning, Metropolitan Planning, Istanbul, Turkey

1. Introduction

While the role and position of regions has become more important with changes in the contemporary global structure, the “regional approach” is also gaining importance in terms of urban planning and urban policy. Regional planning is associated with the concept of “development” commonly. It seems that the regional planning tool integrates diverse spatial programs and is influential in reaching national targets. Urbanization, population growth and urban expansion are current urban phenomena. When urban areas extend beyond their administrative boundaries and are transformed into more complex structures, it is difficult to control and solve local problems. However, regional planning helps to solve these problems and is useful in balancing the development among the different regions of a country (Glasson & Marshall, 2007) .

The regional policies developed in Turkey since the beginning of the Republic have been generated by the social and economic needs of the nation, and influenced by the experiences of European countries (Türk, 2012) . With the establishment of the State Planning Organization (SPO), which was responsible for regional development in the 1960s, regional development became more important. Diverse regional plans were prepared by SPO in line with the national and regional strategies set out in the Five-Year National Development Plans. With these planning practices, the main objective was to reduce regional inequalities.

The regional planning process gained a different dimension when Turkey started to take into account the European Union’s regional policy (Türk, 2012) . This led to the development of structural reforms in Turkey’s regional policies (Göymen, 2004) . Thus, Turkey’s regional planning practices, which initially had the goal of “regional development,” became associated with the objectives of “economic growth” and “competitiveness” over time.

“Regional planning” in Turkey gained more importance in recent years, especially with the implementation of new legal arrangements. With these, new types of regional plans were defined, and in this way regional planning within the Turkish planning hierarchy was strengthened. However, the new regulations integrated into the existing planning system made the system more complicated. First, problems of the existing planning system affected regional planning. On the other hand, the new types of regional plans and their proper place in the existing planning hierarchy were not fully defined, which also led to complexity.

In this study, the challenges of regional planning in Turkey are analyzed through a case study of Istanbul. The city offers fruitful resources for this paper. Through national and local strategy documents, the city has been promoted as a world city, which connects Turkey’s economy to the global system (OECD, 2008) . To strengthen its competitiveness in the global arena, central and local governments have declared global city visions and defined different functions for Istanbul such as a financial center, cultural center, tourism center, etc. in national and regional plans (Baycan-Levent, 2003) . With these diverse visions and many actors, the city is experiencing a plethora of regional planning practices.

After the introduction, first section of the paper provides a brief history of regional planning practice in Turkey, and the second explains the problems of regional planning in Turkey. The third section is built upon the study of the city of Istanbul and reviews itsregional planning experience, with special emphasis on the three challenges derived from actors and power relations, content and methodology, and external factors. The concluding section provides a discussion of the current picture of the regional planning in Istanbul.

2. Regional Planning in Turkey

Regional planning has been important in Turkey since the founding of the Republic, but it has been largely developed since the 1960s, which is called the beginning of the “planned period”. However, the fact that regional planning activities have been more effective and have accelerated in Turkey in recent years is the result of Turkey’s efforts to adapt to European Union (EU) regional policies. New regulatory and institutional arrangements have been made to ensure compliance with EU regional these policies. In this context, the “Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics” (NUTS) classification was first made in 2002, as it was in the EU. Later, in 2006, with the law No. 5449, it was decided to set up development agencies to speed up regional development, ensure sustainability, and reduce interregional and intra-regional development disparities. With the establishment of development agencies, regional planning efforts have accelerated.

In 2011, significant developments occurred regarding the national administrative structure and the planning system in Turkey. These also affected regional planning. New ministries were established, or old ones replaced, and new policies were declared through new regulations, while two of the new ministries were given the most significant roles in regional planning in Turkey. These are the Ministry of Development and the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization.

In 2011, with the establishment of the Ministry of Development, a number of new policy tools for regional development planning were declared. For instance, the responsibility for the establishment and organization of development agencies was given to the ministry. Also, as a new planning tool, a “Regional Development National Strategy” was introduced in the decree on the Organization and Duties of the Ministry of Development (No. 641). It serves to ensure the integrity between developmental policies and spatial development strategies at national and regional levels.

According to the decree, the main goals for preparing the “Regional Development National Strategy” are to coordinate all efforts nationally in terms of regional development and regional competitiveness, to strengthen cohesion between spatial development and socio-economic development policies, and to establish a general framework for sub-scale (regional and provincial) plans and strategies (KB, 2014) .

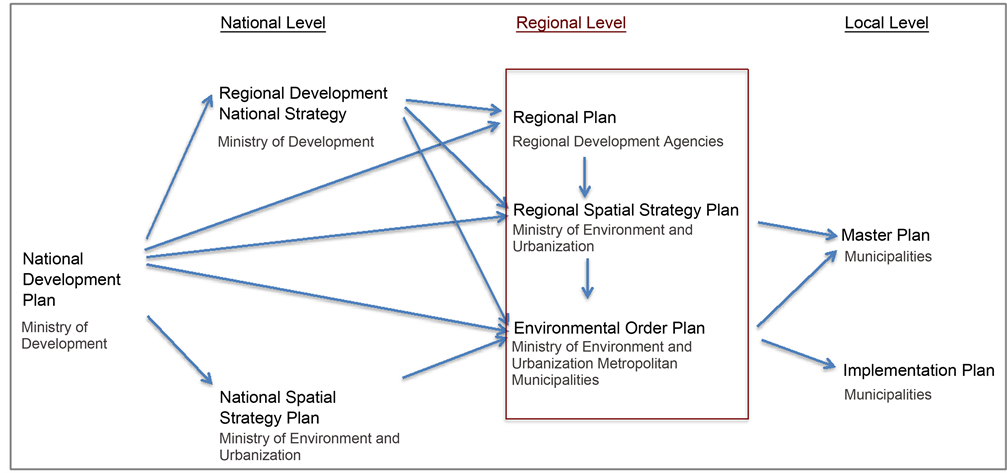

The second important step for improving regional planning was the establishment of the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization, which was established in 2011 under the decree on the Organization and Duties of the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization (No. 644). After the establishment of the ministry, a new regulation, namely the “Preparation of Spatial Plans,” came into effect in 2014. This regulation brought essential changes in the planning system. With this regulation, the existing planning hierarchy (Figure 1) was modified by introducing new planning types such as the “national spatial strategy plan” and the “regional spatial strategy plan”. The formulation of plans was redefined, and institutional tasks were re-determined (Güneri, 2013) .

The main goals of the regulation on the “Preparation of Spatial Plans” are to eliminate the deficiencies of large scale plans, which have no spatial dimension, and to transform some large scale plans, which have comprehensive approaches,

Figure 1. Planning hierarchy in Turkey’s planning system. Source: Author, 2017.

into strategic plans. Therefore, with the regulation on the “Preparation of Spatial Plans,” it is intended that strategic decisions which are defined in the high-level strategic plans are integrated with space. In this context, as a new kind of plan, the “regional spatial strategy plan” was intended to relate national development policies and regional development strategies at the spatial level.

The latest efforts at improving regional planning practice (Figure 2) show that regional planning is gaining more importance in Turkey (Kilic, 2009) . Looking at all recent changes together, it is possible to say that regional planning is becoming more prominent and effective in the Turkish planning agenda.

Defining statistical regions according to EU’s NUTS classifications and establishing development agencies for each region are positive developments for Turkish regional planning. Before the NUTS regional classification, there was no specific determination of the regions in Turkey. Formerly, according to the strategies and priorities of the national development plans, the State Planning Organization (later replaced by the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization) defined some specific areas as regions and prepared regional plans only for those chosen areas. But after NUTS classification, all the lands in the country were allocated to regions, and development agencies were established. Hence, there are now institutions on the regional level, and their main task is to focus on and consider problems in their regions and to prepare regional plans for them.

Another positive change made by new regulations has been to add a spatial dimension to regional plans. As a new regional planning tool, the “Regional Spatial Strategy Plan” helps to relate strategies defined in the national development plan and regional plans to space. It also integrates the regional and local level plans.

On the other hand, in spite of the efforts mentioned above, to improve the Turkish planning system, there are still problems both at the national and regional

Figure 2. The latest efforts at improving regional planning in Turkey. Source: Author, 2017.

levels. In this study, only planning problems at the regional level are presented.

3. Challenges to Regional Planning in Turkey

3.1. Actors and Power Relations

The planning authority in Turkey is fragmented and shared among many different institutions (Metin & Onay, 2015) . In the same area, different institutions can have planning authority. Thus, from time to time, the complexity of the targets of different plans in the same area can be observed. It is also sometimes a matter of debate as to which institution’s plan has priority and will be dominant. The situation is similar with regard to regional planning. This section focuses on the roles and relationships of regional planning authorities in the planning hierarchy.

At the top of the Turkish planning administrative structure is the High Planning Council. The Council functions as an advisory unit for the Cabinet of Ministers on national policies and functions; it is a political mechanism for integrated decision-making in terms of policy formulation (Dodd, 1969) . It is chaired by the Prime Minister and includes cabinet ministers. The issues that constitute the basis for the determination of economic, social and cultural targets and policies are determined by consultation with the High Planning Council. Members of the Council are the President, two Deputy Prime Ministers, the Minister of Development, the Minister of Energy and Natural Resources, the Minister of Finance, the Minister of Forestry and Water Affairs, the Minister of Transport, and the Minister of Maritime Affairs and Communications.

The duties and authorities of the High Planning Council, which are defined in decree 641, include: to assist the Council of Ministers in the planning of economic, social and cultural development, and in determining policy objectives, and to examine the development plans and annual programs in terms of suitability and adequacy regarding the stated objectives, before presentation to the Council of Ministers; to make high level decisions about the domestic and foreign economic life of the country; to determine the principles of investment and export incentives; to approve the Mass Housing Administration budget; and to decide on matters that are authorized by law and other legislation (IBP, 2015) .

After the High Planning Council, there are four main actors responsible for regional development and planning in Turkey. These are the Ministry of Development, the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization, Regional Development Agencies, and Metropolitan Municipalities. The regional planning actors in Turkey are presented below in Figure 3 from national to regional level.

After the High Planning Council, the Ministry of Development and the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization are effective actors on regional planning at the national level. According to the most recent regulations, they have distinctive roles; the Ministry of Development is responsible for preparing “strategic” plans, and the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization is responsible for preparing “spatial” plans at the national level. However, after new regulations defining new spatial plans were enacted, no spatial plan at national level has yet been approved.

Actors at the regional level are the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization, the Regional Development Agencies, and the Metropolitan Municipalities. Regional Development Agencies are responsible for preparing regional plans, which are a strategic type of plan; the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization is responsible for preparing a Regional Spatial Strategy Plan and an Environmental Order Plan, which are both spatial plans; and the Metropolitan Municipalities are also responsible for preparing Environmental Order Plans only for the metropolitan areas. However, after new regulations were enacted, no “regional spatial strategy plan” has yet been approved.

Although new regulations 641, 644 and the regulation on the Preparation of Spatial Plans made regional planning more important within the Turkish planning system, the new kinds of plans and planning authorities introduced by

Figure 3. Regional planning actors in Turkey. Source: Author, 2017.

these regulations have further complicated the existing planning system. First, as mentioned above, the Regional Plan, the Regional Spatial Strategy Plan, and the Environmental Order Plan are plans prepared by three different public institutions at the regional level. Therefore, three plans with the three different institutions are prepared for the same region. Because the differences and relationships between these plans are not fully disclosed, there is confusion about the planning system and hierarchy. In addition, the lack of coordination between different planning authorities creates a conflict of goals and objectives of different plans.

3.2. Content-Methodology Problem

According to the most recent regulations mentioned above, there are Regional Plans, Regional Spatial Strategy Plans, and Environmental Order Plans at regional level in the planning hierarchy in Turkey. However, their contents and the relationships among them remain uncertain.

Although mentioned in different laws, regional plans are not fully defined in planning legislation. It is not clear what the purpose of the regional plan is, what its content should be, how it relates to other plans, and what the methodology of plan making is. Therefore, not infrequently, the goals, objectives and decisions of the plans at the regional or the local level conflict with each other.

There is a short phrase about regional planning in the Zoning Law (No. 3194), which is the basic law on structure and planning. According to this law, regional plans are prepared to determine socio-economic development trends, development potential of the settlements, sectoral targets, distribution of activities and sub-structures (Ozmen, 2013) .

While there is no explanation in the planning legislation on how to prepare the regional plans, the State Planning Organization wrote a Regional Development Plan Preparation Guide in 2010. Regional Plans of the NUTS II Regions were prepared according to this guide.

In the new regulation on the Preparation of Spatial Plans, there is some explanation about the Regional Spatial Strategy Plan, which is introduced for the first time by this regulation. It is said that spatial plans can be prepared in the regions where it is deemed necessary. This means that there is no necessity for the preparation of Regional Spatial Strategy Plans.

In the same regulation, these plans are directed to assess and relate the country’s development policies and regional development strategies at the spatial level; evaluate the economic and social potentials, targets and strategies; review the transportation system and physical thresholds of a regional plan; define spatial strategies regarding protection and development of natural, historical and cultural resources; direct urban and transportation developments and urban facilities; and establish relationships between spatial policies and strategies relating to sectors. These plans are prepared by using schematic and graphical language at the 1/250,000, 1/500,000 scales or higher. Also, sectoral and thematic maps, and a planning report are integral parts of these plans.

In addition to the above problems, the other shortcomings of regional planning in Turkey are the lack of implementation-action planning and economic planning in the regional planning process. From where and how to provide financial resources for implementation of regional and environmental plans are not defined. In addition, there is a lack of monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to check whether the principles and strategies of the plan are implemented or not after plan approval.

3.3. External Factors Effective on Regional Planning

In addition to internal challenges derived from the existing planning hierarchy, there are also external factors which affect regional planning in Turkey. These factors are the High Planning Council’s decisions, plans for “risky” and “reserve” areas and special purpose plans (Figure 4).

3.3.1. High Planning Council Decisions

Urban policy in Turkey has been under pressure from globalization and neoliberalism since the 1980s. As part of an effort to strengthen the competitive position of the country’s metropolitan economies in a global world, the central and local governments have followed an entrepreneurial route. Consequently, governments in Turkey have examined the mechanisms of entrepreneurial governance through new urban policies serving to regulate the deregulation and foster private investment and development from the 1980s to the present.

Over the past twenty years, central authorities with the entrepreneurial governance approach have strongly relied on the implementation of large-scale urban development projects, especially in metropolitan cities. However, these

Figure 4. External factors affecting regional planning in Turkey. Source: Author, 2017.

projects have been poorly integrated into the existing planning system. Moreover, with special powers of intervention and decision-making, governments have frozen regulatory planning tools and bypassed statutory regulations to accelerate and facilitate the realization of large scale urban development projects. The grounds for this effort of governments are that planning and realizing urban development projects in the existing regulatory planning system is a long and difficult process that requires many bureaucratic procedures. Thus to accelerate the formalization and implementation process of urban projects, central government bypasses the planning system and uses an alternative method: to have urban projects approved by High Planning Council.

When the government wants to realize a large-scale urban development project, it presents its project to the High Planning Council through the relevant ministry. The process is defined in the law No. 3996. According to this law, public institutions can make some investments and provide services that require technology or large financial resources by using the “build-operate-transfer (BOT) model.” The administration, which wants to make the investments and provide the services according to BOT, applies to the High Planning Council with a preliminary feasibility study of the project and can be authorized by the Council to carry out such investments and services. After authorization, public institutions can sign contracts with private companies. Many large-scale projects have been implemented in metropolitan cities through this process.

3.3.2. Plans for “Risky” and “Reserve” Areas

Earthquakes have had hazardous effects on the urban areas of Turkey throughout history. After the 1999 Marmara Earthquake, one of the most devastating earthquakes, the central government started to develop plans and projects to minimize the negative effects of future earthquakes. However, these efforts were not satisfactory, and a new regulation called the Regeneration of Areas under Disaster Risk (No. 6306) was enacted in 2012. It is also known as the Urban Regeneration Law. The basic purpose of this law is to define the procedures and principles on planning and transformation of risky areas and risky buildings.

According to the law, the Ministry of Urbanization and Environment is the main institution responsible for preparing plans and applications of the law. As the core issues in the law, three concepts are defined: risky areas, risky buildings and reserve areas. While risky areas are defined as “the areas which may cause loss of life and property due to the properties of the ground or the conditions of the buildings” (Eren & Özcevik, 2015) , reserve areas are defined as areas for “new settlements to be deployed in implementations to be carried out as per this law” (Tarakçı & Özkan 2015) . Both are identified and approved by the Cabinet of Ministers. After a decision, the buildings in a risky area are demolished and redeveloped by the relevant public institution, the Mass Housing Authority (TOKİ),or the private sector.

However, with the law, the central government has acquired superpowers: “the power to decide which area will be subject to regeneration, the power to make plans, and the power to decide which construction company will be enrolled (Eren & Özcevik, 2015) .” As a new powerful and flexible urban regulation tool, the Law No: 6306 is above all a set of planning regulations. It means that central government can “make redevelopment plans and open new development areas in every possible piece of land without any significant restriction” (Eren & Özcevik, 2015) . Therefore, actions which are taken under the law No: 6306 by central government can potentially affect the regional planning system.

3.3.3. Special Purpose Plans

The third external factor which affects regional planning in Turkey is special purpose planning. There are many different laws which give the right to make and approve the plans to different institutions, especially to the ministries for special areas (Unsal, 2009) . The Conservation Plan, Tourism Development Plan, Technology Development Area Plan, Organized Industrial Area Plan, and Special Forest Development Plan are some of the examples of special purpose plans (Metin & Onay, 2015) .

While these types of plans make the existing planning hierarchy more chaotic, they also have another role which makes local authorities less powerful. The role can be defined as “smoothing the path for the development projects” (Erkut & Shirazi, 2014) . The problem emerges from “a tendency of the central government in Turkey which to use planning authority through special purpose plans” (Erkut & Shirazi, 2014) . In the beginning, the function of these plans was to protect and conserve natural and cultural assets. However, the central government has used special purpose plans to accelerate and facilitate large-scale development projects, especially in the last decade.

When the lack of coordination and cooperation between the local governments and the central government is taken into consideration, it can be foreseen that there would be problems derived from developing large-scale urban projects with the help of special purpose plans. These processes make the integration of different plan types difficult and affect the regional planning approach negatively.

4. Problems of Regional Planning in Istanbul

Istanbul has always been a focal point in the country, both before and after the foundation of the republic. Because Istanbul is regarded as the locomotive of Turkey’s economic growth, its development has been given special importance. In this regard, Istanbul also has a special place in terms of the planning experience in Turkey. Istanbul’s diverse planning experience reflects the Turkish planning system. For instance, the Industrial Regional Plan of Istanbul in 1955 is one of the early examples of regional planning in Turkey.

After this first plan, Istanbul has had three other main plans at the regional level until the 2000’s: the 1963 North Marmara Region Plan, the 1980 Metropolitan Area Master Plan, and the 1995 Istanbul Metropolitan Area Subregion Master Plan. This shows that regional planning practices in Istanbul were not dense until the 2000’s. From 2000’s, as a result of Turkey’s efforts to adapt to EU regional policies, new developments regarding regional planning have emerged. First, in 2002, the NUTS regional classification was formulated, and the province of Istanbul was defined as a region at all NUTS levels. After the NUTS classification, as a second important step, the Istanbul Regional Development Agency was established in 2008, and officials started to prepare the Istanbul Regional Plan in 2009. In 2010, the Istanbul Regional Plan, which covers the 2010-2013 period, was approved by the Ministry of Development.

While these developments were occurring, there was another regional planning study initiated by the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality (IMM). In 2004, IMM and the Ministry of Environment and Forestry signed a contract to transfer the Ministry’s planning authority to IMM. Furthermore, IMM started to prepare the Istanbul Environmental Plan, which is, according to the Turkish planning hierarchy, one of the plans made at the regional level. In 2009, the Istanbul Environmental Plan was approved by IMM. In 2014, at the end of the period of the first plan, the Istanbul Development Agency prepared the second Istanbul Regional Plan, which covers the 2014-2023 period.

In this section, the problems of regional planning practice in Istanbul are analyzed with special emphasis placed on actors and power relations in regional planning, external factors affecting regional planning, and the content-metho- dology problem, all mentioned above.

4.1. Actors and Power Relations in Regional Planning in Istanbul

The fragmentation of the planning authority is a chronic problem of the planning system in Turkey. Such a fragmented legal and institutional structure can be clearly witnessed in Istanbul. In many areas of the city, more than one institution is authorized with planning rights leading to an overlapping of jurisdictions. Figure 5 shows the planning authority areas in Istanbul. According to this figure, Ministries have 74% of the planning authority on Istanbul’s land, and IMM has 26% of the planning authority. The rate of 74% shows the fragmented structure of planning in Istanbul. Also, it shows the power of central government and the centralization of planning.

The lack of clarity in the planning environment not only prevents the execution of decisive urban policies, but leads to the cancellation of the plans approved by the councils as well. The case of Istanbul is a stunning example of this failure of planning as the Urban Development Plan of Istanbul Metropolitan Area (1995) and the Environmental Plan of Istanbul (2007) have been cancelled just after coming into force due to their questioning of the authority of the planning institution.

Another problem is the lack of coordination between the institutions. This structure complicates decision-making, as the decisions in one institution’s plans are challenged by another. The planning decision of the third airport in Istanbul is a good example to point out the problem. In the Istanbul Environmental Plan (2009), an area in Silivri District was defined as a third airport area. However, in

Figure 5. Planning authority areas in Istanbul. Source: IMM, 2015.

2012, the Cabinet of Ministers announced a new place for the third airport area in Arnavutkoy District and transferred the planning authority of this place to the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization. The third airport area in Arnavutkoy District had been defined as a forest area in the Istanbul Environmental Plan (2009) and should have been protected as a natural resource.

4.2. Content and Methodology Problem

Istanbul provides several examples of content and methodology problems of regional planning in Turkey, which are explained in the third section. To point out these problems, it is necessary to look at existing plans at the regional level. Although planning legislation defines three types of plans at this level, i.e., the regional plan, the regional spatial strategy plan, and the environmental order plan (see Figure 1), Istanbul does not yet have a regional spatial strategy plan that was first introduced in the regulation on the “Preparation of Spatial Plans” in 2014. By the year 2017, the city only has the Istanbul Regional Plan (2014) and the Istanbul Environmental Order Plan (2009).

Because existing planning legislation does not give broad definitions of the regional plan, regional spatial strategy plan and environmental order plan, this situation creates chaos among them. The Istanbul Regional Plan (IRP) and the Istanbul Environmental Order Plan (IEOP) present these chaotic relationships.

IRP sets out an overall regional development vision, strategies and objectives for the next decade and acts as a guide for planning and investment decisions for Istanbul. As a high level plan, it outlines “Istanbul’s socioeconomic development trends, development potential, high priority intervention areas and sectoral targets, in order to direct those strategic plans to be prepared by public institutions including local governments”.

The vision of the IRP is a “Unique Istanbul: City of Innovation and Culture with Creative and Free Citizens.” With this vision, the format of the plan is engendered from 3 main development axes, 23 priorities, 57 strategies, and 476 objectives and measures.

The plan has been prepared based on a strategic planning system, and hence it has a “strategic” character. However, its strategies are too general and have not been related to the spaces of Istanbul. As an illustration, one of the strategies of the plan, Strategy 1, is defined as “creating an industrial production structure which uses advanced technologies, produces high value-added, and employs skilled labor.” Under this strategy, six objectives are employed to strength ten the strategy. One of them, Objective 6, is about “transforming the industry by taking into account its spatial dimensions; with policies coordinated and integrated with urban renewal in Istanbul.” Therefore, there is an emphasis on the need to transform industry in Istanbul, but there is no determination of the industrial areas which should be transformed. Taking into account the content and the format of the IRP, it is possible to say that the plan includes just general strategies which are too broad for implementation.

Other important issues in the plan are the lack of an action plan and economic planning. In the “Coordination, Monitoring and Assessment” part of the plan, it is explained that “this plan contains high-scale strategies and objectives. To realize all of these strategies and objectives, it is necessary to prepare action plans which define sub-strategy documents in priority areas, resources, and responsibilities.”

Another essential point regarding the IRP is the lack of a monitoring mechanism. In the plan, it is explained that “suggestions and recommendations of the stakeholders regarding implementation of the Plan will be gathered, the problems experienced by the stakeholders in practice will be observed, and information and opinions will be collected for evaluation of the Plan.” However, the methods for monitoring and assessment of the implementation of the plan are not explained. Also, there is even now monitoring and/or assessment report on the process of the implementation of the existing plan.

Second, the actual regional plan in Istanbul is the Istanbul Environmental Order Plan (IEOP) approved in 2009 by IMM. The vision of the IEOP is that “towards environmental, social and economic sustainability principles, to develop while providing conservation of authentic cultural and natural identity and to have global competitiveness and high quality of life.”

The IEOP has strategic and regulatory characteristics. The plan defines strategies and also defines land uses in coherence with its vision and strategies. It is also explained in the planning notes that “this plan is schematic and land use decisions defined in this plan are general and not binding. In the local plans, these land use decisions will be elaborated and finalized.”

The IEOP, different from the IRP, has an action plan called “plan implementation phases.” In this action plan, three different phases have been defined. The first phase includes 18 action targets, which should be achieved within 10 years. The second phase includes 13 targets to be achieved within 10 years. In the third phase, success or failure of the implementation of the plan, which is based on a feedback and monitoring process, is assessed, and provisions and revisions are made if required. However, actors who apply the action plan, methodology, financial sources and monitoring mechanism are not defined in the IEOP. Therefore, an action plan is not binding, and there are no defined public institutions, which are responsible for the implementation and monitoring of the IEOP.

4.3. External Factors Affecting Regional Planning

4.3.1. High Planning Council Decisions

As one of the external factors influencing regional planning in Istanbul, decisions of the High Planning Council have significant implications, not only for regional planning, but for local planning in Istanbul as well.

To integrate Istanbul into the global competitive and economic system, the central government of Turkey has promoted many mega projects in Istanbul. Contemporary, large-scale mega projects are seen as useful tools to accelerate the city’s economic development and to strengthen the capacity of its competitiveness. Under this logic, Istanbul has witnessed a vast number of mega projects, especially over the last fifteen years. Figure 6 shows existing mega projects in Istanbul. The problem here is that most of these projects are not included either in regional plans or in local plans. They are not parts of existing planning decisions, but mostly results of High Planning Council decisions.

4.3.2. Plans for “Risky” and “Reserve” Areas

As explained in the 4th section, “Risky” areas are defined in the regulation on the Regeneration of Areas under Disaster Risk (No. 6306) as areas under risk of

Figure 6. Mega projects in Istanbul. Source: http://megaprojeleristanbul.com, 2017.

natural disaster. When an area is declared as a “risky” area, it has to be subject to urban transformation. As the responsible authority, the Ministry of Urbanization and Environment starts to prepare plans and urban regeneration projects in these risky areas.

After the law No. 6306, also known as Urban Regeneration Law, was enacted, one area as a reserve area and 43 areas as risky areas were declared in Istanbul as of November 2014 (Eren & Özçevik, 2015) . The reserve area, 42,534 hectares in total, is also known as the area of the Kanal Istanbul Project and third airport (Figure 7).

4.3.3. Special Purpose Plans

As mentioned in the 2nd section, the planning authority is fragmented in the Turkish planning system. Numerous institutions develop their own plans in their authorized areas. Hence, there are many different types of special purpose plans in Istanbul, such as conservation plans, tourism development plans, technology development area plans, urban regeneration plans, industrial area plans and so on.

To explain the existing situation of special purpose plans in Istanbul, discussing planning for tourism development provides a good base. According to current regulation (the law No. 2634 for the Encouragement of Tourism), the Ministry of Culture and Tourism has planning authority in the areas of “cultural and tourism preservation and development regions” and “tourism centers.” These areas are defined in the same law as having a high potential for tourism development, and are identified to be evaluated for preservation, utilization, sectoral development and planned improvement. Moreover, their boundaries are determined and declared by the Council of Ministers upon the proposal of the Ministry.

The Ministry of Culture and Tourism has declared many areas in Istanbul as tourism centers (Figure 8). In these areas, the Ministry develops tourism plans with its own planning approach, which promotes private sector investment and

Figure 7. Kanal Istanbul project and third airport area. Source: Ministry of Environment and Urbanization, 2017.

Figure 8. The distribution of tourism centers in Istanbul. Source: Gezici & Kerimoglu, 2010 .

uses a far from holistic regional planning approach.

Like tourism center plans, there are many different plans for special areas in Istanbul. This fragmented structure makes integration and coordination of all plans difficult.

5. Conclusion

Current regulatory and administrative arrangements regarding “regional development” show a common concern about the improvement of regional planning practice in Turkey. With the new instruments, such as the regional development agency, NUTS regional classification, Regional Development National Strategy, and Regional Spatial Strategy Plan, it seems that regional development planning in Turkey is getting more important and powerful. However, there are still some gaps to fill.

Most of the challenges come from the existing structure of the planning system. The role of planning actors, their power relationships and the relationships among plans in the planning hierarchy are not well defined in the actual planning regulations. Diverse planning actors and their targets intersect with each other in diverse types of plans in the same areas. There is a fragmented planning structure in Turkey.

While the existing planning system is fragmented and has problems that need to be solved, improving regional planning in this planning hierarchy is difficult. Despite all difficulties, there are recent efforts to improve regional planning in Turkey. This article has presented new developments regarding regional planning in the country and then explains its challenges through the example of Istanbul. These challenges are analyzed under the three categories of “actors and power relations,” “content and methodology,” and “external factors.”

While regional planning practice in Istanbul is examined in this paper, the challenges discussed above can be clearly seen. As the most important metropolitan area for the economy of Turkey, Istanbul is a large, global city in which many different actors compete to get a share from its tremendous development. Therefore, the city is also a representative place for the implementation of the planning system of Turkey. In this context, regional planning practice in Istanbul illustrates the existing regional planning situation in Turkey.

Cite this paper

Gursoy, N., & Edelman, D. J. (2017). Regional Development Planning in Istanbul: Recent Issues and Challenges. Current Urban Studies, 5, 146-163. https://doi.org/10.4236/cus.2017.52009

References

- 1. Baycan-Levent, T. (2003). Globalization and Development Strategies for Istanbul: Regional Policies and Great Urban Transformation Projects. 39th ISoCaRP Congress: Globalization and Development Strategies for Istanbul, Istanbul. [Paper reference 1]

- 2. Dodd, C. H. (1969). Politics and Government in Turkey. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Paper reference 1]

- 3. Eren, M. O., & Ozcevik, O. (2015). Institutionalization of Disaster Risk Discourse in Reproducing Urban Space in Istanbul. ITU A|Z, 12, 221-241. [Paper reference 4]

- 4. Erkut, G., & Shirazi, M. R. (2014). Dimensions of Urban Re-Development. The Case of Beyoglu, Istanbul. Berlin: TU Berlin. [Paper reference 2]

- 5. Gezici, F., & Kerimoglu, E. (2010). Culture, Tourism and Regeneration Process in Istanbul. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 4, 252-265.

https://doi.org/10.1108/17506181011067637 [Paper reference 1] - 6. Glasson, J., & Marshall, T. (2007). Regional Planning. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. [Paper reference 1]

- 7. Goymen, K. (2004). Türkiye’de Bolge Kavrami ve Politikalarin Gelisimi. AB ve Türkiye’de Bolgesel Yonetisim Uluslararasi Konferansi (pp. 13-39). Istanbul: Pendik Belediyesi. [Paper reference 1]

- 8. Güneri, S. (2013). Cevre Ve Sehircilik Bakanligi’nin Kurulmasi (644 Sayili Khk) Ile Planlama Yetkilerinin Merkezilesmesi Ve Kent Mekanina Etkileri-corlu Ornegi Doctoral Dissertation, Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü. [Paper reference 1]

- 9. IBP (International Business Publications) (2015). Turkey Privatization Programs and Regulations Handbook. [Paper reference 1]

- 10. KB (Kalkinma Bakanligi) (2014). Bolgesel Gelisme Ulusal Stratejisi 2014-2023. Bolgesel Gelisme ve Yapisal Uyum Genel Müdürlügü, Ankara. [Paper reference 1]

- 11. Kilic, S. E. (2009). Proposals for Regional Administrative Structure and Planning in Turkey. European Planning Studies, 17, 1283-1301.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310903053430 [Paper reference 1] - 12. Metin, M. S., & Onay, I. A. (2015). The Role of Urban Governance and Planning in Knowledge City Development: Case Study of Istanbul, Turkey. 10th International Forum on Knowledge Asset Dynamics: IFKAD-Culture, Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Connecting the Knowledge Dots, Italy. [Paper reference 2]

- 13. OECD (2008). OECD Territorial Reviews. Istanbul, Turkey. [Paper reference 1]

- 14. Ozmen, R. (2013). Imar Kanunu. Seckin Yayincilik. [Paper reference 1]

- 15. Tarakci, S., & Ozkan, A. H. (2015). Evaluation of Law no. 6306 on Transformation of Areas under Disaster Risk from Perspective of Public Spaces-Gezi Park Case. ICONARP International Journal of Architecture and Planning, 3, 63-82. [Paper reference 1]

- 16. Türk, M. S. (2012). Regional Development Policies in Turkey in the Integration Process of the European Union. Gazi üniversitesi Iktisadi ve Idari Bilimler Fakültesi Dergisi, 14, 103-124. [Paper reference 2]

- 17. Unsal, F. (2009). Critical Evaluation of Legal and Institutional Context of Urban Planning in Turkey: The Case of Istanbul. International Academic Association on Planning, Law and Property Rights, Aalborg, Denmark, 11-13. [Paper reference 1]