Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

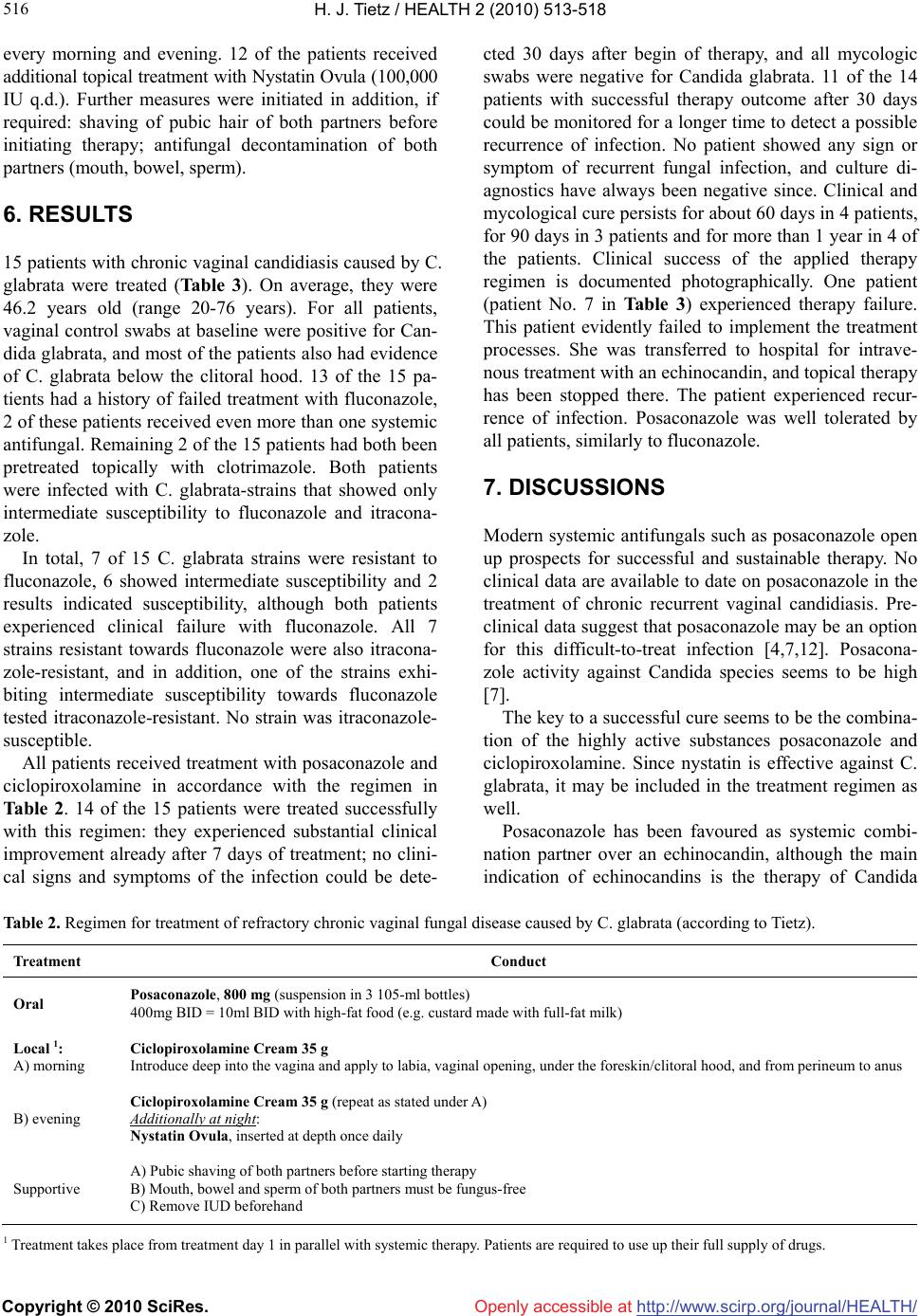

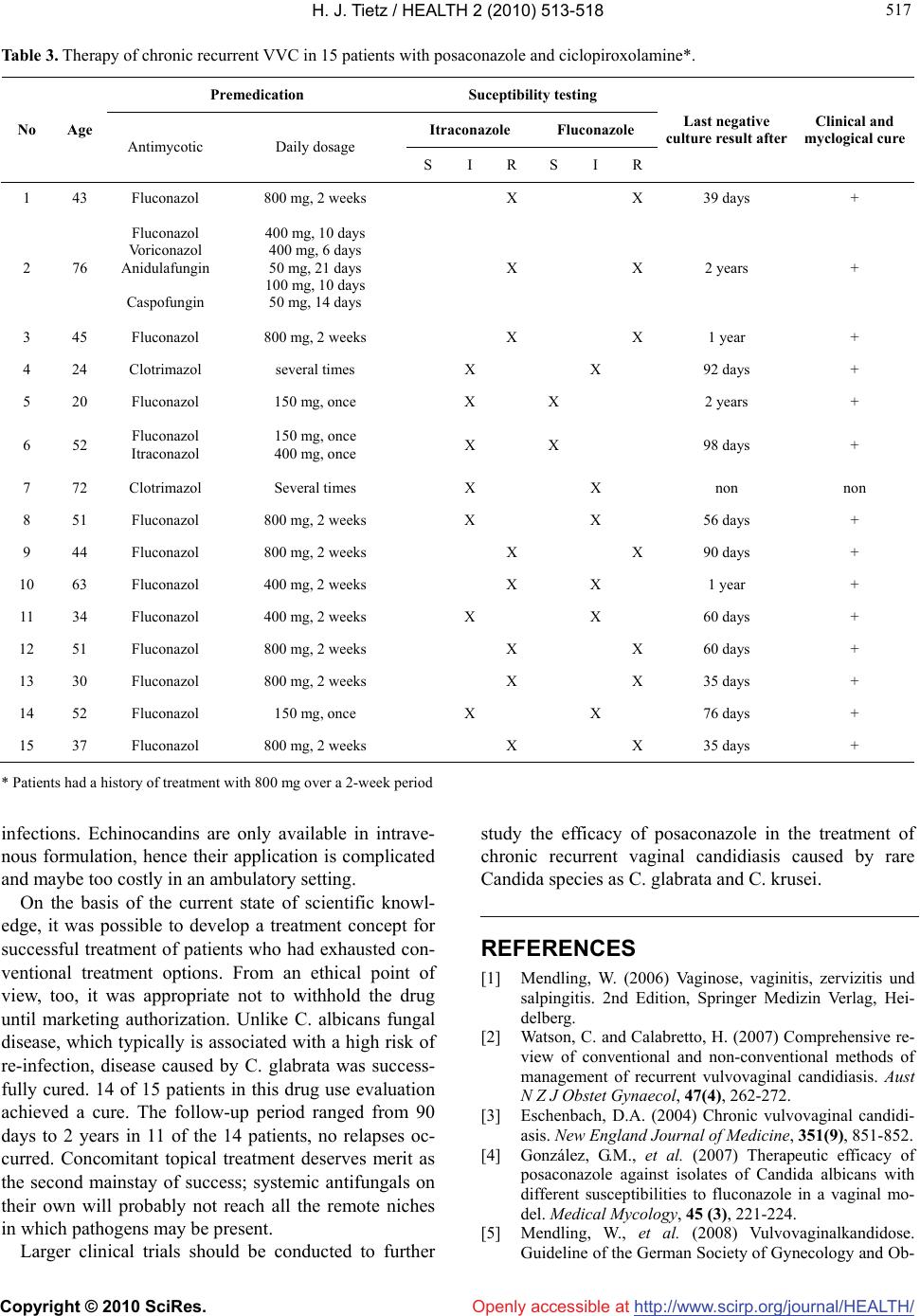

Vol.2, No.6, 513-518 (2010) Health doi:10.4236/health.2010.26077 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Treatment of chronic vulvovaginal candidiasis with posaconazole and ciclopiroxolamine Hans-Jürgen Tietz Fungal Infection and Microbiology Institute, Berlin, Germany; tietz@institut-fuer-pilzkrankheiten.de Received 21 January 2010; revised 30 January 2010; accepted 2 February 2010. ABSTRACT Therapy of chronic recurrent vulvovaginal can- didiasis (VVC) caused by Candida glabrata is still rare in comparison to C. albicans infection, but therapy remains more difficult. Combination therapy with topical antifungals may improve therapy outcome, but still standard agents as fluconazole or itraconazole often fail. Posa- conazole is a new systemic triazole with a wide antifungal spectrum including rare Candida species. Up to now, no clinical trials with posa- conazole in chronic recurrent VVC have been undertaken. Here, first results of the application of a new therapy regimen consisting of oral posaconazole in combination with topical ci- clopiroxolamine are presented. 15 patients with chronic recurrent VVC caused by C. glabrata have been treated. 14 of these patients experi- enced successful therapy, clinical and myco- logical cure 30 days after begin of therapy has been observed. Long-term results are promising, as in 4 patients clinical and mycologic cure persists for more than 1 year up to now. Keywords: Chronic Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis; VVC; Candida Glabrata; Posaconazole 1. INTRODUCTION Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) is termed chronic if it recurs four times or more per year at intervals of 8 weeks or less [1]. Literature data suggest that acute vul- vovaginal candidiasis becomes chronic in 5-8 % of cases [2,3]. Possible, but heatedly debated, risk factors for vaginal thrush include prior antibiotic or corticosteroid therapy, intrauterine contraceptive devices (coil), high- sugar diet, and certain sexual practices [2]. The etiology of chronic recurrent VVC is little understood even today. Gastrointestinal tract as a reservoir for re-infection, re-infection from sexual partner(s), and recurrent disease as a result of persistent colonization have been postu- lated. This last postulate is supported by studies showing recurrent disease to be caused by identical strains in the vast majority of cases [2]. Though C. albicans is the main pathogen in more than 95% of cases of acute infection [4], other species are implicated in chronic infection, chiefly C. glabrata. The characteristic features of Candida albicans and Candida glabrata are listed in Table 1. The pathogenic role of C. glabrata is disputed, but pa- tients who present to a physician with fungal disease caused by these atypical pathogens always report symp- toms. Though vaginal discharge is rare, redness, agoniz- ing itching, and a sour-smelling sticky discharge are characteristic. A diagnosis of “harmless commensal” is therefore both inappropriate and scientifically inaccurate. Both organisms are biosafety class 1 organisms. Hence, though low-virulence, they are not apathogenic—unlike Saccharomyces cerevisiae. 2. TREATMENT OF PROBLEM FUNGI The therapeutic goal in chronic recurrent VVC is the eradication of the pathogen. The chances of achieving that goal appear to be good. Unlike C. albicans, non- albicans Candida organisms are located predominantly vaginally. Measures to prevent recurrence should be ini- tiated before starting therapy [5]. Oral and bowel con- tamination in the patient (3 fecal samples taken on 3 different days) should be investigated, which may result in measures such as professional dental and denture cleaning and eradication of pathogens in the mouth and bowel with amphotericin B or nystatin (C. glabrata) in the form of lozenges or sugar-coated tablets. A hormonal coil is a potential pathogen reservoir and should ideally be removed before therapy. The sexual partner should be involved in treatment too. Colonization of the prostate (sperm sample) and contamination of dentures (smear tests) in older partners should be investigated.  H. J. Tietz / HEALTH 2 (2010) 513-518 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 514 Table 1. Characteristics of C. albicans and C. glabrata as or- ganisms causing vaginal candidiasis. Property C. albicans C. glabrata Etiology Mostly intra partum Frequently iatrogenic Course Acute Chronic Findings Discharge Redness Pruritus Redness Pruritus Virulence class 2 (high) 1 (low) Pseudomycelium Yes No Blastospores midsize, oval Small-cell, round Chlamydospores Yes No Hormone situation Dependent No Antifungal Pathogen susceptibility (S= sensitive, R= re- sistant) Clotrimazole S R Nystatin S S Ciclopiroxolamine S S Fluconazole S R Posaconazole S S Drug of first choice: - topical - systemic Clotrimazole Fluconazole Ciclopiroxolamine Posaconazole Drug therapy should encompass both a topical and a systemic component. C. glabrata is located deep in vaginal tissue-up to 10 layers deep-which explains the high failure rate for local treatment attempts. C. glabrata also thrives in surface locations–under the foreskin, around the clitoris, in the anal folds and pubic hair–and so the effectiveness of systemic therapy is limited. Therefore, combination therapy seems to be necessary to appropriately treat the patient and avoid recurrence of infection. It needs to be stressed that in addition, patient cooperation is crucial, as rigorous, reliable local treat- ment is required in conjunction with properly adminis- tered systemic therapy. C. glabrata isolates have very low sensitivity to flu- conazole and may be resistant in many cases. Secondary resistance is mainly due to two factors: genetic variabil- ity of the pathogen, which develops resistance to flu- conazole at doses below 800 mg, and the fact that many therapists administer fluconazole doses as low as 150 mg [6]. In contrast, in vitro sensitivity to posaconazole is high [7]. Until just a few years ago, systemic high-dose treatment with 800 mg fluconazole was the treatment of first choice [8]. Given the large number of current treat- ment failures, the treatment approach is not advisable today [5]. Nevertheless, the options for treating invasive fungal infection of the kind are better now than ever. The most promising agents according to the current state of scientific knowledge are the triazole derivative posa- conazole and the echinocandins caspofungin and anidu- lafungin. The latter require intravenous dosing and are associated with high treatment costs. Since vaginal can- didiasis is usually treated in an ambulatory setting, these agents are of lesser relevance for treatment. Ciclopiroxolamine is the most effective local drug for treating clotrimazole- and nystatin-resistant organisms [8]. It is the antifungal with the broadest spectrum, as well as showing deep penetration and sporicidal activity. The mechanism of action is polyvalent. Ciclopiroxola- mine’s activity is not limited to the level of ergosterol synthesis. It also targets regions mitochondria and pro- tein synthesis, making it the ideal combination partner for all systemic antifungals. Inhibition of catalase pro- duction is particularly effective, because it disables me- tabolization of toxic H2O2 occurring in the fungal cell. All clinically relevant Candida species are sensitive to ciclopiroxolamine [8]. Posaconazole is a triazole derivative whose mecha- nism of action is based on inhibiting ergosterol synthesis [9]. It is effective against a variety of fungal pathogens. These include all relevant Aspergillus species, the or- ganisms responsible for mycetoma, coccidioidomycosis, chromoblastomycosis, and refractory pathogens like Mucor and Fusarium [10,11]. The spectrum of action also includes Candida and especially the problem pathogens C. glabrata and C. krusei [7,10] which are resistant to fluconazole, itraconazole and voriconazole. Posaconazole’s molecular structure gives it multiple docking sites, so different mutations would have to oc- cur simultaneously for it to be ineffective [12]. In con- trast, a single mutation is enough to induce resistance to fluconazole [12]. Posaconazole has linear kinetics up to a dose of 800 mg [9]. Exposure can be increased by di- vision into two divided doses of 400 mg (10 ml suspen- sion BID), and is further enhanced by dosing together with high-fat food, e.g. custard made with full-fat milk. It has a high volume of distribution (1744 liters), sug- gesting very good distribution. Posaconazole is metabo- lized to a very slight extent and is primarily eliminated with the feces. Posaconazole has the lowest potential for interactions of all systemic azole derivatives, since in- teractions with the CYP system are limited to CYP3A4 inhibition. The most common side effects reported in studies involving a total of 2400 subjects and patients were headache and nausea [9]. Posaconazole is approved for prevention of systemic infection in high-risk he- mato-oncology patients, for salvage therapy of certain  H. J. Tietz / HEALTH 2 (2010) 513-518 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 515 515 invasive mould infections and for the treatment of oro- pharyngeal candidiasis [9]. Up to now, there is no clini- cal data supporting efficacy in treatment of vaginal can- didiasis. In a murine vaginal model, posaconazole re- duced the fungal burden of both fluconazole-susceptible and fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans strains [4]. The difficulty to treat chronic vaginal infections cau- sed by C. glabrata lead to the development of a concept comprising a posaconazole-ciclopiroxolamine combina- tion therapy for patients, who seemed to have exhausted all conventional treatment options. 3. PATIENTS Patients were eligible if they had a chronic vaginal can- didiasis caused by C. glabrata, a history of therapy fail- ure and reduced sensitivity towards licensed antifungals indicated by susceptibility testing. All patients were carefully examined, including mi- crobiologic and dermatologic diagnosis, to exclude non- fungal infections and a non-infectious dermatosis such as lichen ruber, neurodermitis or psoriasis inversa. To avoid recurrence, the patients’ surroundings were care- fully examined mycologically by taking swabs or sam- ples and cultivation on appropriate media (see Diagnos- tic Procedures). This included the partner’s oral cavity, penis and sperm, but also the patient’s oral cavity, vagina, clitoris and faeces. Vaginal swabs of all patients were taken and cultured before start of therapy for species identification and susceptibility testing. Foreign objects as Nuva-Ring or hormonal coil were removed before start of therapy. Therapy response was assessed by clinical and my- cologic examination at 7 and 30 days after end of ther- apy, respectively. For some patients, long-term results up to 2 years after therapy are available. Patients who have been treated here come from all over Germany, so that long-term follow-up is not possible in every case. For mycologic examination, vaginal and clitoris swabs were taken and inoculated as described below. Further follow- up visits are conducted regularly, about every 30 days, the results are presented below. A successful therapy outcome was defined as substan- tial improvement of the patient’s clinical infection signs and symptoms 7 days after start of treatment, as well as persistent clinical and mycologic cure 30 days after be- gin of therapy. All patients were informed about the compassionate use project in depth and about the existing database on posaconazole in antifungal treatment. Health insurance reimbursement was checked and agreed in advance for all patients. 4. DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES For species identification, swabs were inoculated onto chromIDTM Candida agar, bioMérieux Deutschland GmbH, Nürtingen, Germany, which is specific for yeast isolation and direct identification of Candida albicans. Candida albicans colonies are coloured blue by specific hydroly- sis of a hexosaminidase chromogenic substrate after 2 day of incubation at 37°C. The species identification of non-blue-coloured colonies like C. glabrata and C. krusei were examined by their assimilation pattern with the ID 32C yeast identification system, bioMérieux Deutschland GmbH, Nürtingen, Germany. ID 32C sys- tem consists of a single-use disposable plastic strip with 32 wells to perform 29 assimilation tests (carbohydrates, organic acids, and amino acids), 1 assimilation test with a negative control, 1 susceptibility test (cycloheximide), and 1 colorimetric test (esculin) including a database of 63 different species. Results were recorded by direct reading after 48 h of incubation at 30°C. The susceptibility of all isolates towards itraconazole and flucoanzole was tested routinely, as these are the only systemic antifungal agents licensed to treat VVC. FUNGITESTTM, Bio-Rad, Marnes-la Coquette, France was used. In general, this test is used to study growth of yeasts in the presence of 6 antifungal agents at 2 differ- ent concentrations, among them fluconazole and itra- conazole. Growth assessment is based on reduction of the coloured indicator which turns the medium from blue to pink. When growth is inhibited by the fungal agent, the medium remains blue. Two growth and 2 negative controls are included in the test system. The interpreta- tion of the results was performed according the follow- ing colour characteristics: Blue-blue = no growth, strain inhibited by the antifungal agent, sensitive strain (“S”); Pink-blue = low growth, intermediate strain (“I”); Pink- pink = growth, strain not inhibited by the antifungal agent, resistant strain (“R”). The breakpoints have been chosen following the study of the distribution of the an- tifungal agents MIC obtained with prototype microplates used with the same procedure as FUNGITESTTM. If susceptibility testing indicates intermediate susceptibility or resistance towards fluconazole or itraconazole, ther- apy attempts with these agents cannot expect to be suc- cessful because of the genetic haploidy of C. glabrata. 5. THERAPY All patients received a combination of systemic and topical therapy (Table 1). For systemic therapy, posa- conazole was administered for 15 days at a daily dose of 800 mg (10 ml BID). Topical therapy consisted of cicl- opiroxolamine cream BID administered intravaginally  H. J. Tietz / HEALTH 2 (2010) 513-518 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 516 every morning and evening. 12 of the patients received additional topical treatment with Nystatin Ovula (100,000 IU q.d.). Further measures were initiated in addition, if required: shaving of pubic hair of both partners before initiating therapy; antifungal decontamination of both partners (mouth, bowel, sperm). 6. RESULTS 15 patients with chronic vaginal candidiasis caused by C. glabrata were treated (Table 3). On average, they were 46.2 years old (range 20-76 years). For all patients, vaginal control swabs at baseline were positive for Can- dida glabrata, and most of the patients also had evidence of C. glabrata below the clitoral hood. 13 of the 15 pa- tients had a history of failed treatment with fluconazole, 2 of these patients received even more than one systemic antifungal. Remaining 2 of the 15 patients had both been pretreated topically with clotrimazole. Both patients were infected with C. glabrata-strains that showed only intermediate susceptibility to fluconazole and itracona- zole. In total, 7 of 15 C. glabrata strains were resistant to fluconazole, 6 showed intermediate susceptibility and 2 results indicated susceptibility, although both patients experienced clinical failure with fluconazole. All 7 strains resistant towards fluconazole were also itracona- zole-resistant, and in addition, one of the strains exhi- biting intermediate susceptibility towards fluconazole tested itraconazole-resistant. No strain was itraconazole- susceptible. All patients received treatment with posaconazole and ciclopiroxolamine in accordance with the regimen in Table 2. 14 of the 15 patients were treated successfully with this regimen: they experienced substantial clinical improvement already after 7 days of treatment; no clini- cal signs and symptoms of the infection could be dete- cted 30 days after begin of therapy, and all mycologic swabs were negative for Candida glabrata. 11 of the 14 patients with successful therapy outcome after 30 days could be monitored for a longer time to detect a possible recurrence of infection. No patient showed any sign or symptom of recurrent fungal infection, and culture di- agnostics have always been negative since. Clinical and mycological cure persists for about 60 days in 4 patients, for 90 days in 3 patients and for more than 1 year in 4 of the patients. Clinical success of the applied therapy regimen is documented photographically. One patient (patient No. 7 in Table 3) experienced therapy failure. This patient evidently failed to implement the treatment processes. She was transferred to hospital for intrave- nous treatment with an echinocandin, and topical therapy has been stopped there. The patient experienced recur- rence of infection. Posaconazole was well tolerated by all patients, similarly to fluconazole. 7. DISCUSSIONS Modern systemic antifungals such as posaconazole open up prospects for successful and sustainable therapy. No clinical data are available to date on posaconazole in the treatment of chronic recurrent vaginal candidiasis. Pre- clinical data suggest that posaconazole may be an option for this difficult-to-treat infection [4,7,12]. Posacona- zole activity against Candida species seems to be high [7]. The key to a successful cure seems to be the combina- tion of the highly active substances posaconazole and ciclopiroxolamine. Since nystatin is effective against C. glabrata, it may be included in the treatment regimen as well. Posaconazole has been favoured as systemic combi- nation partner over an echinocandin, although the main indication of echinocandins is the therapy of Candida Table 2. Regimen for treatment of refractory chronic vaginal fungal disease caused by C. glabrata (according to Tietz). Treatment Conduct Oral Posaconazole, 800 mg (suspension in 3 105-ml bottles) 400mg BID = 10ml BID with high-fat food (e.g. custard made with full-fat milk) Local 1: A) morning Ciclopiroxolamine Cream 35 g Introduce deep into the vagina and apply to labia, vaginal opening, under the foreskin/clitoral hood, and from perineum to anus B) evening Ciclopiroxolamine Cream 35 g (repeat as stated under A) Additionally at night: Nystatin Ovula, inserted at depth once daily Supportive A) Pubic shaving of both partners before starting therapy B) Mouth, bowel and sperm of both partners must be fungus-free C) Remove IUD beforehand 1 Treatment takes place from treatment day 1 in parallel with systemic therapy. Patients are required to use up their full supply of drugs.  H. J. Tietz / HEALTH 2 (2010) 513-518 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 517 517 Table 3. Therapy of chronic recurrent VVC in 15 patients with posaconazole and ciclopiroxolamine*. Premedication Suceptibility testing Itraconazole Fluconazole No Age Antimycotic Daily dosage S I R S I R Last negative culture result after Clinical and myclogical cure 1 43 Fluconazol 800 mg, 2 weeks X X 39 days + 2 76 Fluconazol Voriconazol Anidulafungin Caspofungin 400 mg, 10 days 400 mg, 6 days 50 mg, 21 days 100 mg, 10 days 50 mg, 14 days X X 2 years + 3 45 Fluconazol 800 mg, 2 weeks X X 1 year + 4 24 Clotrimazol several times X X 92 days + 5 20 Fluconazol 150 mg, once X X 2 years + 6 52 Fluconazol Itraconazol 150 mg, once 400 mg, once X X 98 days + 7 72 Clotrimazol Several times X X non non 8 51 Fluconazol 800 mg, 2 weeks X X 56 days + 9 44 Fluconazol 800 mg, 2 weeks X X 90 days + 10 63 Fluconazol 400 mg, 2 weeks X X 1 year + 11 34 Fluconazol 400 mg, 2 weeks X X 60 days + 12 51 Fluconazol 800 mg, 2 weeks X X 60 days + 13 30 Fluconazol 800 mg, 2 weeks X X 35 days + 14 52 Fluconazol 150 mg, once X X 76 days + 15 37 Fluconazol 800 mg, 2 weeks X X 35 days + * Patients had a history of treatment with 800 mg over a 2-week period infections. Echinocandins are only available in intrave- nous formulation, hence their application is complicated and maybe too costly in an ambulatory setting. On the basis of the current state of scientific knowl- edge, it was possible to develop a treatment concept for successful treatment of patients who had exhausted con- ventional treatment options. From an ethical point of view, too, it was appropriate not to withhold the drug until marketing authorization. Unlike C. albicans fungal disease, which typically is associated with a high risk of re-infection, disease caused by C. glabrata was success- fully cured. 14 of 15 patients in this drug use evaluation achieved a cure. The follow-up period ranged from 90 days to 2 years in 11 of the 14 patients, no relapses oc- curred. Concomitant topical treatment deserves merit as the second mainstay of success; systemic antifungals on their own will probably not reach all the remote niches in which pathogens may be present. Larger clinical trials should be conducted to further study the efficacy of posaconazole in the treatment of chronic recurrent vaginal candidiasis caused by rare Candida species as C. glabrata and C. krusei. REFERENCES [1] Mendling, W. (2006) Vaginose, vaginitis, zervizitis und salpingitis. 2nd Edition, Springer Medizin Verlag, Hei- delberg. [2] Watson, C. and Calabretto, H. (2007) Comprehensive re- view of conventional and non-conventional methods of management of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol, 47(4), 262-272. [3] Eschenbach, D.A. (2004) Chronic vulvovaginal candidi- asis. New England Journal of Medicine, 351(9), 851-852. [4] González, G.M., et al. (2007) Therapeutic efficacy of posaconazole against isolates of Candida albicans with different susceptibilities to fluconazole in a vaginal mo- del. Medical Mycology, 45 (3), 221-224. [5] Mendling, W., et al. (2008) Vulvovaginalkandidose. Guideline of the German Society of Gynecology and Ob-  H. J. Tietz / HEALTH 2 (2010) 513-518 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 518 stetrics, German Dermatologic Society, German-Spea- king Mycologic Society, Berlin. [6] Czaika, V., et al. (2000) Antifungal susceptibility testing in chronically recurrent vaginal candidosis as basis for effective therapy. Mycoses, 43(Suppl 2), 45-50. [7] Pfaller, M.A., et al. (2001) Vitro activities of posacona- zole (Sch 56592) compared with those of itraconazole and Fluconazole against 3,685 clinical isolates of Can- dida spp. and Cryptococcus neoformans. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 45(10), 2862-2864. [8] Tietz, H.J. and Sterry W. (2006) Antimykotika von A-Z., Thieme, 4.Auflage, Stuttgart. [9] Smith, W.J., Drew, R.H. and Perfect, J.R. (2009) Posa- conazole’s impact on prophylaxis and treatment of inva- sive fungal infections: an update. Expert Review of Anti- Infective Therapy, 7(2), 165-181. [10] Herbrecht, R. (2004) Posaconazole: A potent, extended spectrum triazole antifungal for the treatment of serious fungal infections. International Journal of Clinical Pra- ctice, 58(6), 612-624. [11] Schiller, D.S. and Fung, H.B. (2007) Posaconazole: An extended spectrum triazole antifungal agent. Clinical Th- erapeutics, 29(9), 1862-1886. [12] Hof, H. (2008) Is there a serious risk of resistance de- velopment to azoles among fungi due to the widespread use and long-term application of azole antifungals in medicine? Drug Resistance Updates, 11(1-2), 25-31. |