J. Biomedical Science and Engineering, 2010, 3, 602-611 doi:10.4236/jbise.2010.36082 Published Online June 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jbise/ JBiSE ). Published Online June 2010 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/jbise Medication compliance among mentally Ill patients in public clinics in Kingston and St. Andrew, Jamaica Andrea E. Pusey-Murray1, Paul A. Bourne1, Stan Warren2, Janet LaGrenade1, Christopher A. D. Charles3 1Department of Community Health and Psychiatry, Faculty of Medical Sciences University of the West Indies, Kingston, Jamaica; 2Department of Sociology, Psychology and Social Work, The University of the West Indies, Mona, Jamaica; 3King Graduate School, Monroe College, Bronx, New York and Center for Victim Support, Harlem Hospital Center, New York, USA. Email: paulbourne1@yahoo.com Received 26 February 2010; received 5 April 2010; accepted 15 April 2010. ABSTRACT The Bellevue and the Hagley Park mental health outpatient clinics in Jamaica serve the majority of psychiatric patients in the country, but there is a dearth of research on medication compliance, which is a very important mental health issue. Medication compliance affects intervention outcomes. Therefore, this study seeks to examine medication compliance among psychiatric patients in Jamaica. A 33-item questionnaire which included items on demographics, health conditions, medication compliance and in- sightfulness was administered to a sample of 370 par- ticipants with a response rate of 93%. The majority of the participants have schizophrenia, followed by depression, bipolar disorder and drug-induced psy- chosis. The majority of the participants (65.3%) did not comply with their prescribed medication regimen. Medication compliance was significantly related to: gender (P < 0.05) where males were more likely to take the prescribed medication, family support (P < 0.05) where the participants who received family support (the majority being males) were more likely to take the prescribed medication, and insightfulness (P < 0.05) where the majority of participants with insightfulness were females. Locus on control was not statistically tested but a majority of the non- compli- ant participants reported that factors external to themselves had greater control over their disorder. Conclusion: There are three significant factors that explain the medication compliance of psychiatric pa- tients in Jamaica. An important non-tested factor is locus of control so there needs to be more research to understand the range of factors that can inform and improve patient education about medication compli- ance. Keywords: Medication Compliance; Mentally Ill; Public Clinics; Kingston; St. Andrew 1. INTRODUCTION Mental illness such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorders and uni-polar depression presents a serious health care problem in Caribbean countries such as Jamaica and worldwide. The economic, clinical, and personal bur- dens associated with schizophrenia make it a leading public health problem. The earliest epidemiological re- port on schizophrenia in the Caribbean was from Ja- maica [1], and indicated that the annual population inci- dence rate was 150 per 100,000. Burke [2] confirmed this finding, and reported an annual incidence rate of 136 per 100,000. Both studies were based on mental hospital admission rates, and it is likely that these studies failed to access the total number of admissions for the island. A study of psychiatric admissions to private and public hospitals across Jamaica [3] reported that the incidence rate of schizophrenia had fallen from 69 per 100,000 in 1960 to 35 per 100,000 in 1990. Antipsychotic drugs, the most effective treatment for acute episodes or exacerbations of schizophrenic illness [4], allow many patients to leave institutions and live in the community [5]. Rates of relapse among patients with schizophrenia who receive medication are two to three times lower than those among patients receiving placebo [6], and non-compliance increases the frequency of acute psychotic episodes and psychiatric hospitalization [7]. Although antipsychotic drugs can have serious adverse effects [8], many clinicians prescribe them at moderate doses for as long as possible to prevent relapse. In addi- tion to antipsychotic agents, patients with schizophrenia may receive lithium, antidepressants, or benzodiazepines for concomitant psychiatric disorders [4]. Mental health research and pharmaceutical innovation have developed a class of drugs referred to as “atypical  A. E. Pusey-Murray et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 602-611 603 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE antipsychotics”, which are used for the treatment of se- vere schizophrenics who are considered treatment- re- sistant to traditional or conventional antipsychotic med- ications, or who experience side-effects severe enough to require that the patient discontinue use of conventional antipsychotics [9]. These atypical antipsychotics are tremendously effective in combating the symptoms of schizophrenia while avoiding the severe side-effects often experienced through treatment with conventional antipsychotics [10]. In Jamaica medications for treating mental health problems are limited and their availability varies district by district. Older antipsychotic drugs are usually available, but there is only limited availability of the newer, more expensive anti-psychotics. In the North East, some patients are treated with clozapine by special arrangement by the district psychiatrist [11]. Adherence to drug regimen is a very important factor for improvement. Adherence may be defined as the ex- tent to which a person’s behaviour confirms to medical or health advice [12]. Patient who do not follow the treatment schedule and drug regimens prescribed to them by physician can be described as noncompliant or not adherent [13]. Medication compliance among bipolar disorder patients is related to the constructs of the health belief model (HBM) such as benefits and barriers, sus- ceptibility and perceived seriousness [14]. However, the compliance/non-compliance of patients is only moder- ately predicted by the HBM. The HBM does not cover some determinants of medication compliance such as social influence and treatment alliance [15]. Patients with bipolar disorder who are medication compliant per- ceive the quality of their life to be higher, have greater resources to cope with stress and have a stronger belief that their behaviour controls their health status, unlike non-compliant patients [16]. The patients’ perception of the medication is important because cognitive disso- nance suggests that the perceptual properties of the medication have particular meanings for the patients. These meanings can support or distract the patients from medication compliance [17]. Patients with a major de- pressive disorder who have a superior medication com- pliance index are more likely to show improved scores on the Hamilton Depression Scale [18]. The medication events monitoring system (MEMS) used in a study with schizophrenic disorder patients reveals a 63% mean compliance rate for the first month and a decline from 56% to 45% over the next five months. The medication compliance of these patients can be monitored with electronic monitoring devices, but data recovery and compliance require methodological improvements [19]. Among patients with psychotic disorders there was a significant relationship between medication adherence and involuntary admission, substance abuse, not gradu- ating from school, and a history of abusive behaviour. Patients with paranoid or negative symptoms were less compliant in taking their medication. However, patients who were changed from a typical to an atypical antipsy- chotic medication were more compliant than patients who remained on the typical antipsychotic medication. The patients who had higher medication compliance experienced much greater improvement of their psychi- atric symptoms [20]. Medication self-management am- ong patients with schizophrenia or affective disorder is important for medication compliance. However, patients who are self-managing their medication, guided by the principles of motivational interviewing, have better atti- tudes towards medications and insights about their ill- ness compared to controls, but the group difference is not significant [21]. Patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and uni- polar depression, who were educated about the nature of their disorder and its pharmacological management, were more compliant in outpatient follow-ups, and dis- played less fear of being addicted to the medication and dealing with the side effects of the drug [22]. Severely mentally ill patients who were a part of the Medication Usage Skills for Effectiveness (MUSE) Program that taught cueing, life skill techniques, visual feedback and about the data displayed on the medication cap showed an overall mean compliance rate of 76%, compared to a 57% compliance rate for the control group [23]. The problem of poor adherence to therapeutic regimen has been a matter of concern to the professionals for years. The paucity of data on cost-related medication adherence problems has important implications not only for estimating their clinical significance, but also for understanding the extent to which adherence problems vary across socioeconomic groups. To our knowledge there has not been any study that has examined drug compliance among mentally ill patients in Jamaica who are treated with oral antipsychotics. The aim of this study was to examine the medication compliance of psychiatric patients in Jamaica. 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS 2.1. Sample In Jamaica the single mental hospital is Bellevue Mental Hospital in Kingston. Its three acute care wards of 50 beds each serve a designated geographic catchment area of the parishes of Kingston, St. Andrew, and St. Cath- erine, a population that is 70 percent urban [24]. Of the hospital’s patients, 40% are older than 65 years, 60% of them are regarded as chronically ill, and 300 of them have lived in the hospital for most of their adult lives. The University Hospital West Indies (UHWI), also lo- cated in Kingston, has a 20-bed psychiatric unit. It is an acute unit with an average length of stay of 15 days. Ja-  604 A. E. Pusey-Murray et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 602-611 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE maica’s rural and western regions are served partly by Cornwall Regional Hospital. This 60-bed unit offers a full range of services, but only 30 beds are used because of staff shortages [11]. The Bellevue Hospital in Kingston and the Hagley Park Health Centre in Saint Andrew investigated in this study are two of the main psychiatric clinics in Jamaica. They attend to in excess of 90% of the psychiatric out-patient cases in the country. The current study used cross-sectional survey to gather the data from partici- pants. Using a sampling error of ± 3.0% and a 95% con- fidence interval, the calculated sample size was 370 par- ticipants. Based on the proportionality of cases seen over the last 2 months, this was used to proportion the sample size from each institution: 200 participants from the Bellevue Hospital Clinic and 170 from the Hagley Park Health Centre. The response rate was 93.0% with 186 participants from the Bellevue Outpatient Clinic and 158 from the Hagley Park Health Centre. Data was collected over a three-month period, from March to May, 2008. A team of trained data collectors were retrained in keeping with the peculiarities of the task. The researcher was a part of the process, and regu- lar checks were done to ensure consistency among inter- viewers. The inclusion/exclusion criterion was based on mental illness and medication use. Mentally ill patients who were visiting the clinics for the first time were ex- cluded from the study because they would not have de- veloped a pattern of medication compliance (or non- compliance). 2.2. The Instrument A 33-item questionnaire was used to collect the data. The questions included: 1) demographic information, 2) medication compliance, 3) reasons for taking (or not taking) medication, 4) accessibility and affordability of medication, 5) use and prevalence of home remedies, 6) family support and 7) perception of the management of mental illness (Appendix 1). 2.2.1. Test-and-Pretesting the Instrument The instrument was developed in consultation with aca- demics at the University of the West Indies, Mona, Ja- maica, caregivers/guardians at the Harbour View Health Centre in St. Andrew, health practitioners, and non- prospective mentally ill patients for the sample. The in- strument was modified in keeping with the comments of the various stakeholders, with specific emphasis on mentally ill patients’ perspectives, suggestions and rec- ommendations. A pilot of 50 questionnaires was tested at the Harbour View Health Centre on ill patients, and they provided useful information regarding ambiguities, which was then used to modify the final instrument. 2.3. Measure Non-compliance in medication denotes the failure or refusal of an individual to take the prescribed medica- tion(s) as recommended by the medical practitioner. Compliance is adhering to the prescription of oral or other forms of medication as stipulated by the medical practitioner. It was measured using the item “I take my medication as instructed by the doctor.” The options ranged from always, most times, occasionally and rarely, to never. Compliance for this study is taken to be only a response of ‘always’. Health condition is an illness or ailment diagnosed by the medical practitioner, and this was taken from the medical record of the participant. Insightfulness was measured by the questions: 1) “Do you have a sense of the likelihood of being ill or of when your illness is likely to occur?” 2) Should medication only be taken when one is experiencing symptoms of illness?” and 3) “Will counselling on how to take medications help you to take them better?” The options were yes, no, or unsure. If the answers to all three questions were yes, it was coded as insight, if no was selected in any question it was coded as lack of insight, and unsure was coded as undecided. Non-responses were treated as missing, and not included in any categorization. 2.4. Ethics and Informed Consent The survey was submitted and approved by the Univer- sity of the West Indies Medical Faculty’s Ethics Com- mittee. Participants and/or caregivers gave voluntary consent to their participation in the study. In order to ensure confidentiality, the personal information (i.e. name, address) of the participants was taken from the questionnaires and discarded, after which the other in- formation was entered and stored for data-analysis. 2.5. Statistical Percentages were used to provide background informa- tion on the demographic characteristics of the sample, knowledge of the medication and self-reported informa- tion. Chi-square tests were utilized to examine whether statistical associations existed between non-metric de- pendent and independent variables. A P-value of < 5% (i.e. 95% confidence interval) was used to determine the statistical associations between the variables. 3. RESULTS 3.1. Demographic Characteristic of Sample There were 344 participants in the sample, of which 53.7% (n = 185) came from the Day Clinic at Bellevue Hospital and 64.2% (n = 159) came from the Hagley Park Health Centre. Most of the sample were diagnosed  A. E. Pusey-Murray et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 602-611 605 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE with schizophrenic disorder (58.7%, n = 202), with other health conditions being depression (13.1%, n = 45), bi- polar disorder (10.5%, n = 36), and drug-induced psy- chosis (4.7%, n = 16). Sixty-two percent (n = 212) of the sample had secondary level education; 64.8% were un- employed; 93.0% lived with either parents, partner, children, sibling or in a nursing home; 84.1% had family support; 80.5% were not in a union relationship (unmar- ried, 58.7%; separated, 13.4%: divorced, 4.6%; widowed, 3.8%); 10.5% were married; 44.7% complied with the instruments of the medical practitioners in regards to medication usage; and the mean age was 43.6 years (± 1.5 years). The most common reasons among those who did not comply with the specifications of the medications (55.3%, n = 189) were ‘medication makes me feel too drowsy’ – 19.0%; ‘I was out of medication’ – 18.0%; ‘I forgot’ – 16.9%; and ‘medications make me feel worse’ – 10.1%. The majority of the participants (76.2%, n = 262) in- dicated that they were able to purchase the medications. The participants indicated that if the medication was not available at the hospital or health centre, they would purchased them from a private pharmacy (65.1%), wait for the next appointment in order to see if it was now available (16.6%), and used a home remedy (0.6%). According to Table 1, no significant statistical rela- tionship was found between the type of medical facility utilized and, gender, employment status, education or age (P > 0.05); nor for compliance (P > 0.05) or in- sightfulness (P > 0.05). However, an association did exist between the type of medical facility utilized and marital status (P < 0.05). Twenty-four percent of those who utilized the Hagley Park Health Care Centre were in intimate unions (relationships), compared to 15.6% of those who visited the Bellevue Hospital. Gender was the only demographic variable that was associated with diagnosed health conditions (P < 0.05; Table 2). Most of the participants were diagnosed with schizophrenic disorder, with more males than females with the illness. Females were more likely to be diag- nosed with bipolar disorder and depression than males. However, there were more males diagnosed with drug-induced psychosis (5.9%) than females (2.8%). A statistical relationship was found between gender and compliance/non-compliance of participants (P < 0.05). Males were more likely to comply with the speci- fications of their medication (51%) than females (35.9%). In addition, significant statistical associations were found between family support and compliance/non- compliance (P < 0.05), and family support and gender of respondents (P < 0.05). Males (59.7%) had more family support compared with females (40.3%), and more of Table 1. Demographic characteristics of sample. Hagley Park Clinic (n = 158) Outpatient Day clinic at Bellevue (n = 186) Va riab le n (%) n (%) P Gender NS Male 92 (58.2) 110 (59.1) Female 66 (41.8) 76 (40.9) Marital status < 0.05 Married 16 (10.1) 20 (10.8) Common-law 22 (13.9) 9 (4.8) Widowed 8 (5.1) 5 (2.9) Divorced 6 (3.8) 10 (5.4) Separated 16 (10.1) 30 (16.1) Unmarried 90 (57.0) 112 (60.0) Employment status NS Employed 48 (28.5) 54 (29.0) Unemployed 112 (70.9) 128 (68.8) Other 1 (0.6) 4 (2.2) Education NS Primary or below 36 (30.4) 66 (35.5) Secondary (including vocational) 100 (63.3) 112 (60.2) Tertiary 10 (6.3) 8 (4.3) Compliance NS Yes 65 (41.1) 88 (47.8) No 93 (58.9) 96 (52.2) Insightfulness NS Insight 83 (52.5) 83 (44.9) Undecided 3 (1.9) 15 (8.1) Lack insight 72 (45.6) 87 (47.0) Age Mean (SD) 42.1 years (1.4) 44.1 years (1.2) NS NS not significant those with family support complied with the specifica- tions of the medications (53.3%). Approximate thirty seven percent (37.3%) of the par- ticipants were knowledgeable about the medication they were taking. Sixty-two percent of those who were knowledgeable about the medication indicated that they received the information from their medical doctors, 16.9% from pharmacists and 15.4% from nurses. Con- currently, when they were asked to state who was re- sponsible for controlling their illness, one-half (50%) indicated their medical doctor was responsible for con- trolling their illness, nurse 10.5%, pharmacists 9.0%, God 9.0%, self 4.1%, and other 3.5%. The majority of the participants indicated that apart from medication and other health care professionals, other factors that controlled their illness were: praying (52.4%), cigarettes (11.0%), smoking marijuana (10.5%), fasting (5.05), leaves from sour-sop tree (3.5%) and Obeah (0.3%). A cross-tabulation between gender and insightfulness revealed a significant statistical associa- tion (P < 0.05). Lacking insightfulness was greatest for males (68.6%) and insightfulness was greatest among f emales (50.0%).  606 A. E. Pusey-Murray et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 602-611 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE Table 2. Diagnosed mental illness by demographic characteristic Health condition Schizophrenia n = 202 Bipolar Disorder n = 36 Depression n = 45 Drug Induced psychosis n = 16 Other n = 7 Undiagnosed n = 38 P Characteristic n (%) n (%) n (%) n (%) n (%) n (%) Gender < 0.05 Male 125 (61.9) 19 (9.4) 22 (10.9) 12 (5.9) 2 (1.0) 22 (10.9) Female 77 (54.2) 17 (12.0) 23 (16.2) 4 (2.8) 5 (3.5) 16 (11.3) Age group NS ≤ 20 years 1 (0.5) 1 (2.8) 12 (26.7) 1 (6.2) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 21 – 39 years 90 (44.6) 18 (50.0) 23 (51.1) 12 (75.0) 4 (57.1) 10 (26.3) 40 – 59 years 87 (43.1) 17 (47.2) 10 (22.2) 3 (18.8) 2 (28.5) 23 (60.5) 60+ years 24 (11.9) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 1 (14.2) 5 (13.2) Marital status NS Married 17 (8.4) 5 (13.9) 9 (20.0) 3 (18.7) 2 (28.6) 1 (2.6) Common-law 14 (6.9) 4 (11.1) 8 (17.8) 2 (12.5) 1 (14.3) 1 (2.6) Widowed 8 (4.0) 1 (2.8) 1 (2.2) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 2 (5.3) Divorced 10 (4.9) 2 (5.6) 2 (4.4) 1 (6.3) 0 (0.0) 2 (5.3) Separated 28 (13.9) 4 (11.1) 5 (11.2) 2 (12.5) 1 (14.3) 6 (15.8) Unmarried 125 (61.9) 20 (55.5) 20 (44.4) 8 (50.0) 3 (42.8) 26 (68.4) Employment Status NS Employed 48 (48.5) 14 (14.1) 13 (13.1) 6 (6.1) 2 (2.0) 16 (16.2) Unemployed 150 (62.5) 21 (8.8) 32 (13.3) 10 (4.2) 5 (2.1) 22 (9.2) Other 4 (80.0) 1 (20.0) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) Education NS Primary or below 73 (36.1) 6 (16.7) 16 (35.6) 3 (18.8) 3 (42.8) 13 (34.2) Secondary 119 (58.9) 27 (75.0) 27 (60.0) 11 (68.8) 4 (57.1) 24 (63.2) Tertiary 10 (5.0) 3 (8.3) 2 (4.4) 2 (12.5) 0 (0.0) 1 (2.6) NS not significant 4. DISCUSSION In this study, the majority of the participants were diag- nosed with schizophrenia, followed by depression, bipo- lar disorder and drug induced psychosis which is consis- tent with other findings in the medical literature [1,2]. The majority (84.1%) of the participants have family support, but of this amount only 54% complied with taking the medication as prescribed. This suggests that family support is a significant determinant of medication compliance. This finding corroborates that of Garcia and colleagues, that the support from family caregivers pre- dicts the use of psychiatric medication [25]. According to Hickling [26] family members of mentally ill patients in Jamaica take on the ongoing tasks of monitoring the patient and supervising his or her medication program. Along with the patient and the community mental health service providers, family members participate in formu- lating and carrying out plans for treatment and voca- tional rehabilitation. Although such family involvement is not unique, the extent to which the Jamaican commu- nity mental health service has to rely on the extended family is noteworthy. Most (80.5%) of the participants were not in a stable intimate partner relationship, a fact which could have influenced the amount and the quality of social support they received. Possible explanations could be the nega- tive stigma associated with mental disorders in Jamaica and their inability to provide financially in such a rela- tionship, since 64.8% of the participants were unem- ployed. However, in Jamaica, the fear and stigma asso- ciated with mental illness has been greatly reduced, mental illness is openly discussed in the media, and pa- tients are comfortable receiving treatment for a variety of psychiatric conditions in public and private commu- nity treatment facilities [27]. Medication compliance among the participants in our study was very low with only 44.7% taking their medi- cation. Among those participants who did not comply with the medication specifications (55.3%), 19% of this group indicated they experienced drowsiness, and 10.1% indicated that they felt worse. According to Feuertein et al. [28] estimates of noncompliance ranges between 4% and 92%, with average from 30 to 35 percent. The reason for non- compliance among the participants in this study could be due to a number of factors such as: discomfort resulting from treatment (side effects of medication), expense of treatment, problems of filling a prescription, decision based on personal value, judgment or religious or cultural beliefs about the advantages and  A. E. Pusey-Murray et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 602-611 607 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE disadvantages of the proposed treatment, maladaptive personality, traits or coping style (for example the denial of illness), the stigma attached to drugs for mental health conditions and lack of understanding about the nature of the illness [29]. According to Demyttenwere, the dropout rate of psy- chiatric patients is attributed to various factors, such as illness and patient’s characteristics, time taken to im- prove or poor doctor-patient relationship [30]. Mann indicated that the variance between what the doctors prescribe and what the patients take can be reduced by the doctor listening more carefully to the patients and addressing their concerns about the side effects of the medication [31]. In addition, educating the patients about their disorder, pharmacological management and addressing their concerns and fears of being addicted to the drug increases their compliance [32]. In our study, 18% among the noncompliant participants suggested that their medication was finished, and 16.9% indicated that they forgot to take their medication. These patients can be instructed about life skill techniques, cueing, about Table 3. Compliance by demographic characteristic and health condition. Compliance n = 153 Non-compliance n = 189 Va riab le n (%) n (%) P Gender < 0.05 Male 102 (66.7) 98 (51.9) Female 51 (33.3) 91 (48.1) Age group NS ≤ 20 years 1 (0.7) 2 (1.1) 21 – 39 years 59 (38.6) 87 (46.0) 40 – 59 years 68 (44.4) 85 (45.0) 60+ years 25 (16.3) 15 (7.9) Marital status NS Married 11 (7.2) 28 (14.8) Common-law 16 (10.5) 12 (6.4) Widowed 8 (5.2) 5 (2.6) Divorced 6 (3.9) 10 (5.3) Separated 17 (11.1) 28 (14.8) Unmarried 95 (62.1) 106 (56.1) Employment status NS Employed 40 (26.1) 59 (31.2) Unemployed 112 (73.2) 127 (67.2) Other 1 (0.7) 3 (1.6) Education NS Primary or below 56 (36.6) 56 (29.6) Secondary 88 (57.5) 124 (65.6) Tertiary 9 (5.9) 9 (4.8) Health condition NS Schizophrenia 92 (60.1) 108 (57.1) Bipolar disorder 14 (9.1) 22 (11.6) Depression 20 (13.1) 25 (13.2) Drug-induced psychosis 5 (3.3) 11 (5.8) Other 5 (3.3) 2 (1.2) Undiagnosed 17 (11.1) 21 (11.1) NS not significant Table 4. Family support by demographic characteristic and health condition. Family support Yes n = 290 No n = 37 Va riab le n (%) n (%) P Gender < 0.05 Male 173 (59.7) 15 (40.5) Female 117(40.3) 22 (59.5) Age group NS ≤ 20 years 3 (1.0) 11 (29.7) 21 – 39 years 129 (44.5) 20 (54.1) 40 – 59 years 126 (43.5) 6 (16.2) 60+ years 32 (11.0) 0 (0.0) Marital status NS Married 26 (9.0) 2 (5.4) Common-law 36 (12.4) 2 (5.4) Widowed 15 (5.2) 2 (5.4) Divorced 11 (3.8) 2 (5.4) Separated 31 (10.7) 5 (13.5) Never married 171 (58.9) 24 (64.9) Employment status NS Employed 74 (25.5) 18 (48.6) Unemployed 213 (73.5) 18 (48.7) Other 3 (1.0 1 (2.7) Education NS Primary or below 95 (32.8) 13 (35.1) Secondary 181 (62.4) 22 (59.5) Tertiary 14 (4.8) 2 (5.4) Health condition NS Schizophrenia 173 (59.7) 15 (40.5) Bipolar disorder 31 (10.7) 4 (10.8) Depression 36 (12.4) 8 (21.6) Drug-induced psychosis 13 (4.5) 3 (8.2) Other 7 (2.4) 0 (0.0) Undiagnosed 30(10.3) 7 (18.9) Compliance Yes 154 (53.3) 10 (27.8) <0.05 No 135 (46.7) 26 (72.2) NS not significant the medication data displayed on the cap, and about audiovisual feedback as this kind of instruction increases medication compliance among psychiatric patients [33]. Interventions to increase medication compliance through patient education in Jamaica are necessary because only a minority (37.3%) of the participants reported that they were knowledgeable about the medication they were taking, and the majority (76.2%) of the participants in dicated that they were able to buy their medication, so the cost of the drug was not a prohibitive factor. Medical doctors can play a major role in this regard because 62.0% of the participants who were knowledgeable  608 A. E. Pusey-Murray et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 602-611 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE about their medication stated that they received informa- tion from their doctor. There is a significant relationship between marital status and the clinic used, because 24.0% of the partici- pants used the Hagley Park Health Centre Clinic com- pared to 15.6% for the Bellevue Clinic. This is a sur- prising finding which requires more research. One pos- sible explanation for this finding is that the Bellevue Hospital is the oldest and only major psychiatric hospital in Jamaica. It is heavily stigmatized given the very nega- tive perception Jamaicans have toward mental disorders and people with mental disorders. Therefore, it is possi- ble that the married participants attended the Hagley Park Clinic to avoid the very negative stigma associated with the Bellevue Clinic. Many chronically ill patients take less of their medi- cation than has been prescribed, owing to cost concerns, especially those patients with low incomes, multiple chronic health problems, or no prescription drug cover- age [34]. The consequences of cost-related medication underuse include increased emergency department visits, psychiatric admissions, nursing home admissions, as well as decreased health status [35]. In Jamaica there is government assistance for low-income patients. Ac- cording to McKenzie, few patients ask for it. In his study, in one clinic, none of those who were prescribed medi- cation (at least 35) asked for assistance, despite the fact that none of them were working. It is customary for families to pay for their relatives’ medication. Caregiv- ers considered a lack of money and the need to pay for prescriptions as a deterrent for attending the clinic [11]. There is a significant relationship between gender and psychiatric disorder which is an unexpected finding. A majority of males and females were diagnosed with schizophrenia, with a higher incidence among males. More males than females were diagnosed with drug- induced psychosis, while more females were diagnosed with depression and bipolar disorder than males. Further research is required to understand the nuances of the relationship between gender and mental disorder which is an under-researched area. In addition, there is a related significant relationship between gender and medication compliance, in which males were more likely to comply with their medication. This finding may be explained by the significant relationship between insightfulness about medication and gender, where males account for 68.0% of the participants who lacked insightfulness. This find- ing suggests that it is possible that there is greater medi- cation compliance among males, because they are less insightful about their medication and its side effects than females. It is also possible that since the majority (59.7%) of participants with family support are males, the social support increases medication compliance in this group [25]. In the present study, non-compliance of medication- taking among those with bipolar disorder and depression was over 80%. Lack of insight [36] is a factor associated with poor drug compliance. Hummer and Fleischacker [37] explained that non-compliance with medication is owing to the patients’ perception that the illness is not serious to enough to warrant treatment compliance. Conversely, a study by Cramer and Rosenheck found that 58% of those diagnosed with psychosis and 65% of those with depression complied with the treatment pre- scription [38], which is significantly higher than a simi- lar group in Jamaica. One researcher admitted that the side effects of neuroleptics are real, but can be managed [39], which clearly is accepted by those diagnosed with drug psychosis and bipolar disorder in Jamaica Patients’ belief in their ability to control their illness is very important for medication compliance. However, the participants in our study believed in a range of external factors apart from medication that could be used to con- trol their disorder. These external factors are: praying, use of Obeah (Jamaican witchcraft), fasting, smoking marijuana or use of sour-sop leaves, and smoking ciga- rettes. There are also some participants (69.5%) who believed that doctors, nurses and pharmacists were re- sponsible for controlling their disorder. Thus the major- ity of the participants in our study displayed an external locus of control (rather than an internal locus of control) which downplays the belief that they themselves have major control over what happens in their lives and their wellbeing. This can clearly has an effect on medication compliance. These findings are corroborated by the findings of Volis and colleagues, that the locus of con- trol is important in medication compliance because it mediates the relationship between medication compli- ance and social support [40,41]. This study has contributed to the literature by un- earthing a range of factors that are significantly related to medication compliance among psychiatric patients in Jamaica, which increases our understanding of this very important health issue. There are some limitations to our study. While our sample was taken from the two public mental health clinics that treat the majority of psychiatric cases in the country, these clinics are located in the met- ropolitan region of Kingston. Therefore, it is possible that our sample did not capture psychiatric patients from other urban centres and rural areas. Therefore only cau- tious generalizations should be made. In addition, there is the possibility of social desirability bias, where some of the patients told the interviewers what they wanted to hear to get their approval. It is also possible that the pa- tients’ mental disorders affected the accuracy of their self-reports. Despite the aforementioned fact, medication non-compliance among schizophrenic patients in this research was low and in keeping with another in a non- Caribbean nation which found that it ranges between  A. E. Pusey-Murray et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 602-611 609 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE 24-90% [42]. This work also concurs with the findings of the Jamaican Ministry of Health, which found that medication compliance among schizophrenia patients in Jamaica was 69% [43]. 6. CONCLUSIONS Medication compliance among males is about average, but is extremely low among females. The majority of the participants with an average age of 43.6 years from the Bellevue and Hagley Park mental health outpatient clin- ics do not comply with their medication regimen for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression and psycho- sis among other disorders. This non-compliance can be explained by three significant factors. These are gender, which is related to the factor of reduced insightfulness about taking medication and family support. Non- com- pliance may also be explained by the locus of control which was not tested in this study, but the majority of the noncompliant participants believe that factors exter- nal to them have greater control over their illness than they do. The current study highlights the challenge for public health practitioners and policy makers in ad- dressing this high non-compliance of medication among the mentally ill in Jamaica. A pertinent finding of this study is the fact that the level of education did not change compliance (or non-compliance) among mentally ill patients, suggesting that there is a need for more re- search to unearth the range of factors that influence medication compliance, the belief system of mentally ill patients, an examination of alternative approaches to the treatment of mental illness, and a social intervention programme that is geared towards holistic education strategies in patient care. What is evident from the study is the fact that medication compliance can be explained by 1) the perception of the severity of the illness and the usefulness of the relevant medication, and 2) the per- ceived side-effects of prescribed medications. Medication non-compliance places mentally ill pa- tients at great risk of exacerbation of their symptoms, homelessness and interruptions in their daily lives, so much so that this has become a public health concern which must be addressed with urgency and care. Family support emerged as a positive determinant of medication compliance, suggesting that public health practitioners must begin to explore the role of social support in treat- ing mentally ill individuals, as well as aiding in the drive for increased medication compliance among these indi- viduals. REFERENCES [1] Royes, K. (1962) The incidence and features of psycho- sis in a Caribbean community. Journal of Social Psy- chiatry, 2, 1121-1125. [2] Burke, A.W. (1974) First admissions and planning in Jamaica. Journal of Social Psychiatry, 9, 39-45. [3] Hickling, F.W. (1991) Psychiatric hospital admission rates in Jamaica, 1971 and 1988. British Journal of Psy- chiatry, 159, 817-821. [4] Kane, J.M. and Marder, S.R. (1993) Psychopharma- cologic treatment of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull, 19, 287-302. [5] Crane, G.E. (1973) Clinical psychopharmacology in its 20th year: Late, unanticipated effects of neuroleptics may limit their use in psychiatry. Science, 181, 124-128. [6] Davis, J.M. and Gierl, B. (1984) Pharmacological treat- ment in the care of schizophrenic patients. In: Bellack, A.S., Ed. Treatment and care for schizophrenia. Grune & Stratton, Orlando. [7] Johnson, D.A. (1988) Drug treatment of schizophrenia. In: Bebbington, P. and McGuffin, P., Eds. Schizophrenia: The major issues. Heinemann Professional, Oxford, 158- 171. [8] Ellenbroek, B.A. (1993) Treatment of schizophrenia: A clinical and preclinical evaluation of neuroleptic drugs. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 57, 1-78. [9] Kane, J., Honigfeld, G., Singer, J., et al. (1988) Clozap- ine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic. A dou- ble-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Archives of General Psychiatry, 45, 789-796. [10] Tuunainen, A., Wahlbeck, K. and Gilbody, S.M. (2002) Newer atypical antipsychotic medication in comparison to clozapine: A systematic review of randomised trials. Schizophrenia Research, 56, 1-10. [11] McKenzie, K. Jamaica: Community mental health services. http://www.publications.paho.org/english/Jamaica_CD_1 83. pdf [12] Bruer, J.T. (1982) Methodological rigor and citation frequency in patient compliance literature. American Journal of Public Health, 72, 911-1123. [13] Razali, M.S. and Yahya, H. (1995) Compliance with treatment in Schizophrenia: A drug intervention program in a developing country. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 91, 331-335. [14] Montgomery, L.A. (2002) The relationship between health belief model constructs and medication compli- ance in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and En- gineering, 62(12-B), 5974. [15] Cohen, N.L., Parikh, S.V. and Kennedy, S.H. (2000) Medication compliance in mood disorders: Relevance of the Health Belief Model and other determinants. Primary Care Psychiatry, 6(3), 101-110. [16] Lund, V.E. (2000) Perceived quality of life for persons with bipolar disorder: The role of medication compliance, family and health stress, level of coping, and health locus of control. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 60(7-B), 3198. [17] Buckalew, L.W. and Sallis, R.E. (1986) Patient compli- ance and medication perception. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 42(1), 49-53. [18] Thompson, C., Peveler, R.C., Stephenson, D. and McKen- drick, J. (2000) Compliance with antidepressant medica- tion in the treatment of major depressive disorders in  610 A. E. Pusey-Murray et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 602-611 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE primary care: A randomized comparison of fluoextine and a tricyclic antidepressant. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(3), 338-343. [19] Diaz, E., Levine, H.B., Sullivan, M.C., et al. (2001) Use of the Medication Events Monitoring System to estimate medication compliance in patients with schizophrenia. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 26(4), 325-329. [20] Janssen, B., Gaebel, W., Haerter, M., Komaharadi, F., Lindel, B. and Weinmann, S. (2006) Evaluation of fac- tors influencing medication compliance in patient treat- ment of psychotic disorders. Psychopharmacology, 187 (2), 229-236. [21] Hayward, P., Chan, N., Kemp, R. and Youle, S. (1995) Medication self-management: A preliminary report on an intervention to improve medication compliance. Journal of Mental Health, 4(5), 511-517. [22] Seltzer, A., Roncari, I. and Garfinkel, P.E. (1980) The effect of patient education on medication compliance. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 25(8), 638-645. [23] Cramer, J.A. and Rosenheck, R. (1999) Enhancing medi- cation compliance for people with serious mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 187(1), 53-55. [24] (1993) Demographic Statistics, Jamaica 1992. Statistical Institute of Jamaica, Kingston. [25] Garcia, J.I., Chang, C.L., Young, J.S., Lopez, S.R. and Jenkins, J.H. (2006) Family support predicts psychiatric medication use among Mexican American individuals with schizophrenia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41(8), 624-631. [26] Hickling, F.W. (1975) An analysis of the 1873 Mental Hospital Law in Jamaica and its effect on mental treat- ment facilities. Jamaica Law Journal, 64-69. [27] Hickling, F.W. (1994) Community psychiatry and dein- stitutionalization in Jamaica. Hospital & Community Psychiatry, 45, 1122-1126. [28] Feuertein, M., Labbe, E.E. and Kuegmierezyk, A.R. (1986) Health psychology: A psychobiological perspec- tive. Pleneum Press, New York. [29] Adewuya, A.O., Ola, B.A., Mosaku, S.K., Fatoye, F.O. and Eegunranti A.B. (2006) Attitude towards antipsy- chotics among outpatients with schizophrenia in Nigeria. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 113, 207-211. [30] Demyttenwere, K. (1997). Compliance during treatment with antidepressants. Journal of Affective Disorder, 43, 27-39. [31] Mann, J.J. (1986) How medication compliance affects outcome. Psychiatric Annals, 16(10), 567-570. [32] Seltzer, A., Roncari, I. and Garfinkel, P.E. (1980) The effect of patient education on medication compliance. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 25(8), 638-645. [33] Cramer, J.A. and Rosenheck, R. (1999) Enhancing medi- cation compliance for people with serious mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 187(1), 53-55. [34] Safran, D.G., Neuman, P., Schoen, C., et al. (2002) Pre- scription drug coverage and seniors: how well are states closing the gap? Health Affairs, W253-W268. [35] Tamblyn, R., Laprise, R., Hanley, J.A., et al. (2001) Ad- verse events associated with prescription drug cost- sharing among poor and elderly persons. Journal of the American Medical Association, 285, 421-429. [36] Kane, J.M. (1985) Compliance issues in outpatient treat- ment. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 5, 22-27. [37] Hummer, M. and Fleischhacker, W.W. (1999) Ways of improving compliance. In: Lader, M. and Naber, D., Eds., Difficult clinical problems in psychiatry. Martin Dunitz, London, 229-238. [38] Cramer, J.A. and Rosenheck, R. (1998) Compliance with medication regimens for mental and physical disorders. Psychiatric Services, 49, 196-201. [39] Chen, A.M. (1991) Non-compliance in community psy- chiatry: A review of clinical interventions. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 42(3), 282-287. [40] Voils, C.I., Steffens, D.C., Flint, E.P. and Bosworth, H.B. (2005) Social support and locus of control as predictors of adherence to antidepressant medication in an elderly population. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychia- try, 13(2), 157-165. [41] Meehan, A.J. (1995) From conversion to coercion: The police role in medication compliance. Psychiatric Quar- terly, 66(2), 163-184. [42] Perkins, D.M. (2002) Predictors of non-compliance in patients with schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychia- try, 63(12), 1121-1181. [43] (2008) Mental health and substance abuse unit. Annual Report, Ministry of Health, Jamaica (MOH), Kingston.  A. E. Pusey-Murray et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 602-611 611 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. JBiSE Appendix Question Particular Ques 1-8 Demographic characteristics Gender; age at last birth day; educational level; marital status; Employment status; source of income; whom do you live with Ques 9 Do they assist or support you in taking care of your conditions? Ques 10 What is your diagnosis? Ques 11 Do you know what medication(s) you are taking? Ques 12 How many different types of medication do you take daily? One; Two; Three; Four; Five; Six or more Ques 13 Are you on monthly injection for psychiatric illness? Ques 14 How often are you to take your medication? Daily, less than three times per week; more than three times per week Ques 15 I take my medication as prescribed by my doctor Always; most times; Sometimes; Rarely; Never Ques 16 What are the reasons for not taking your medication as is prescribed? Ques 17 Did you take the medication this morning? Yes or no Ques 18 I know when I will become sick? Strongly agree; agree; unsure; disagree; strongly disagree Ques 19 Medication should only be taken if you are experiencing a symptom of mental illness? Strongly agree; agree; unsure; disagree; strongly disagree Ques 20 Were you told about the medication that you are taking? Yes or no Ques 21 If yes (Ques 20), whom? Doctor; Nurses; Pharmacist; Other Ques 22-30 Questions on medication availability; health care insurance coverage; dispensary of medication; waiting time for medication dispensary Ques 31 Will counselling on how to take medications help me to take them better?

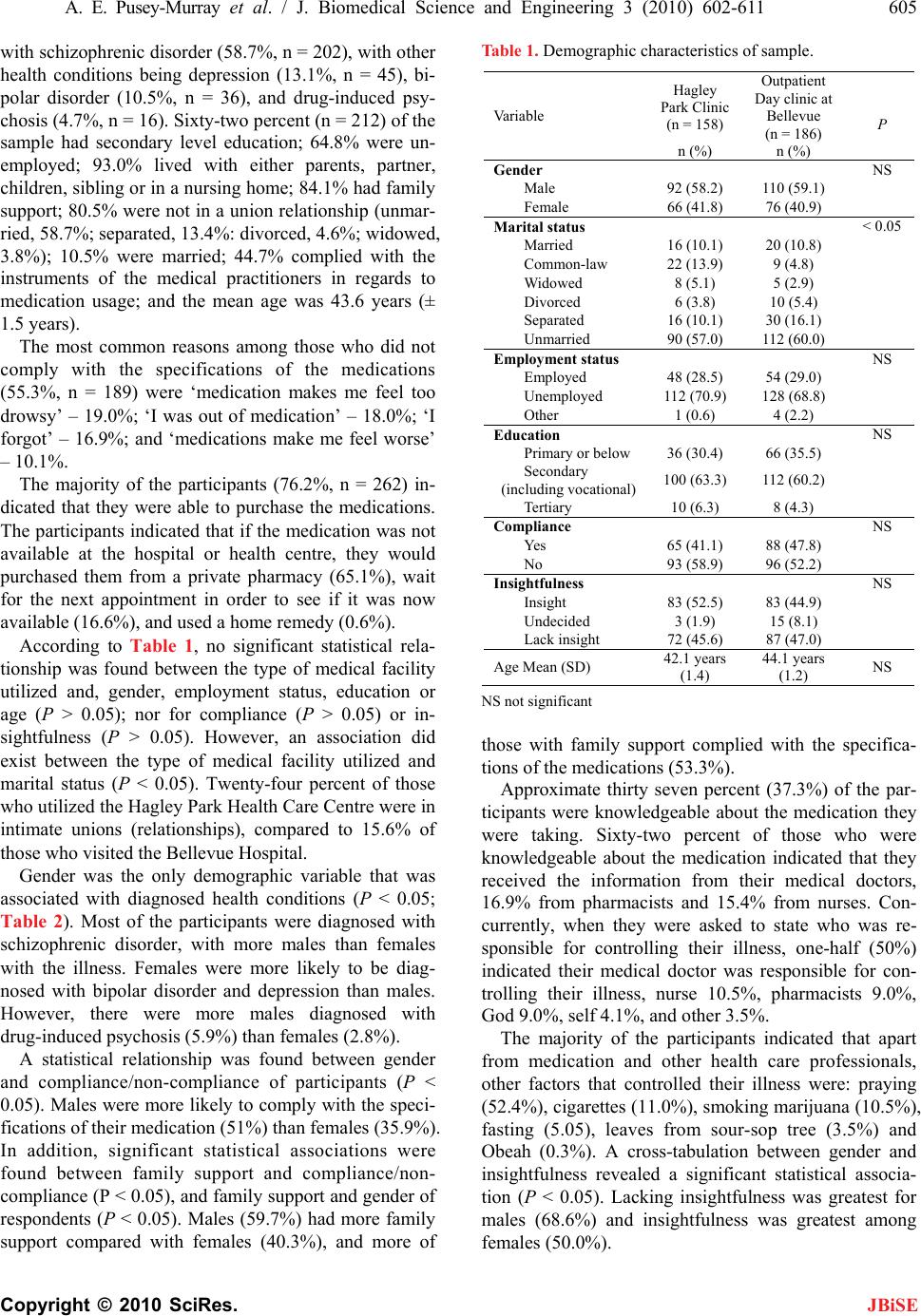

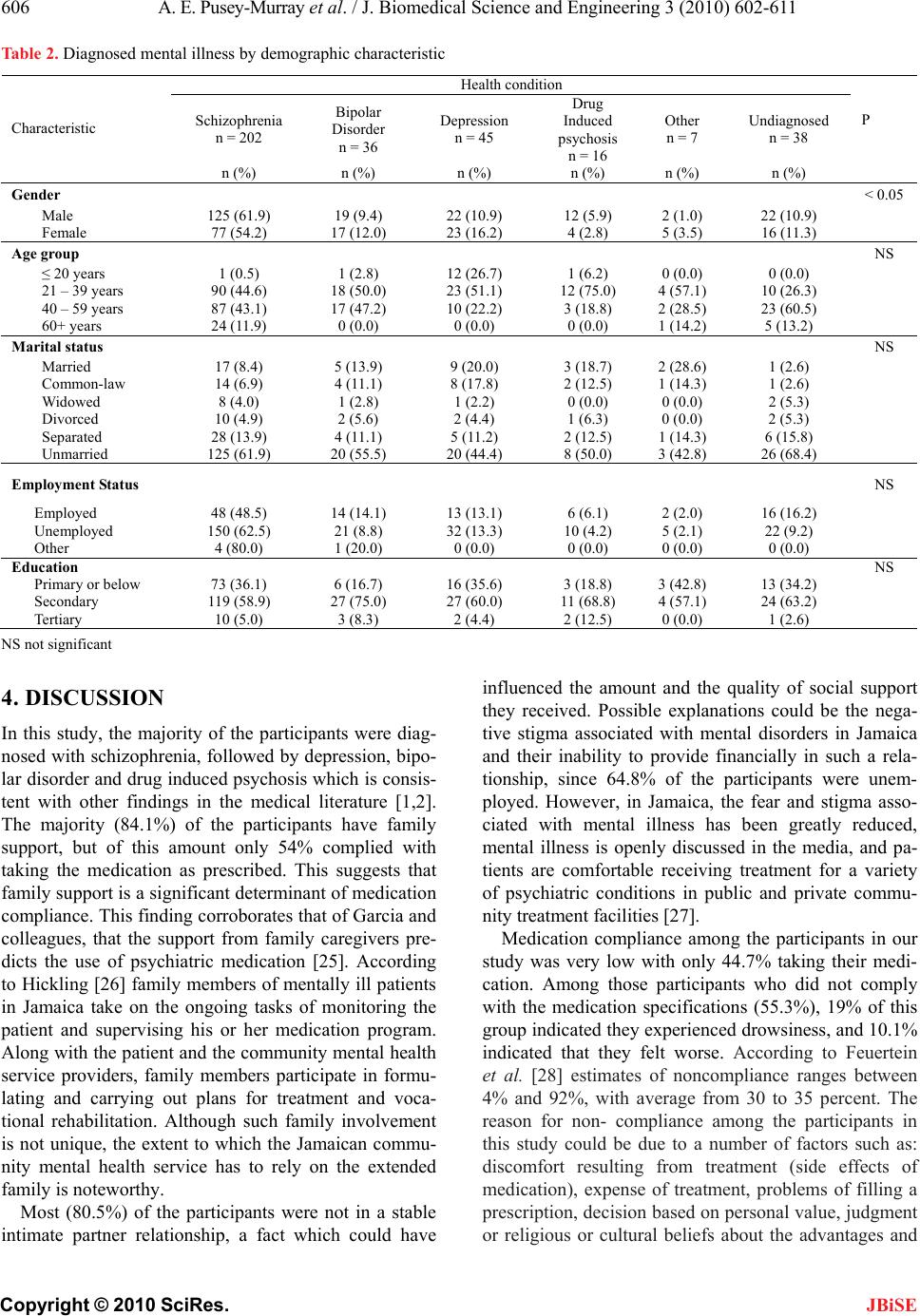

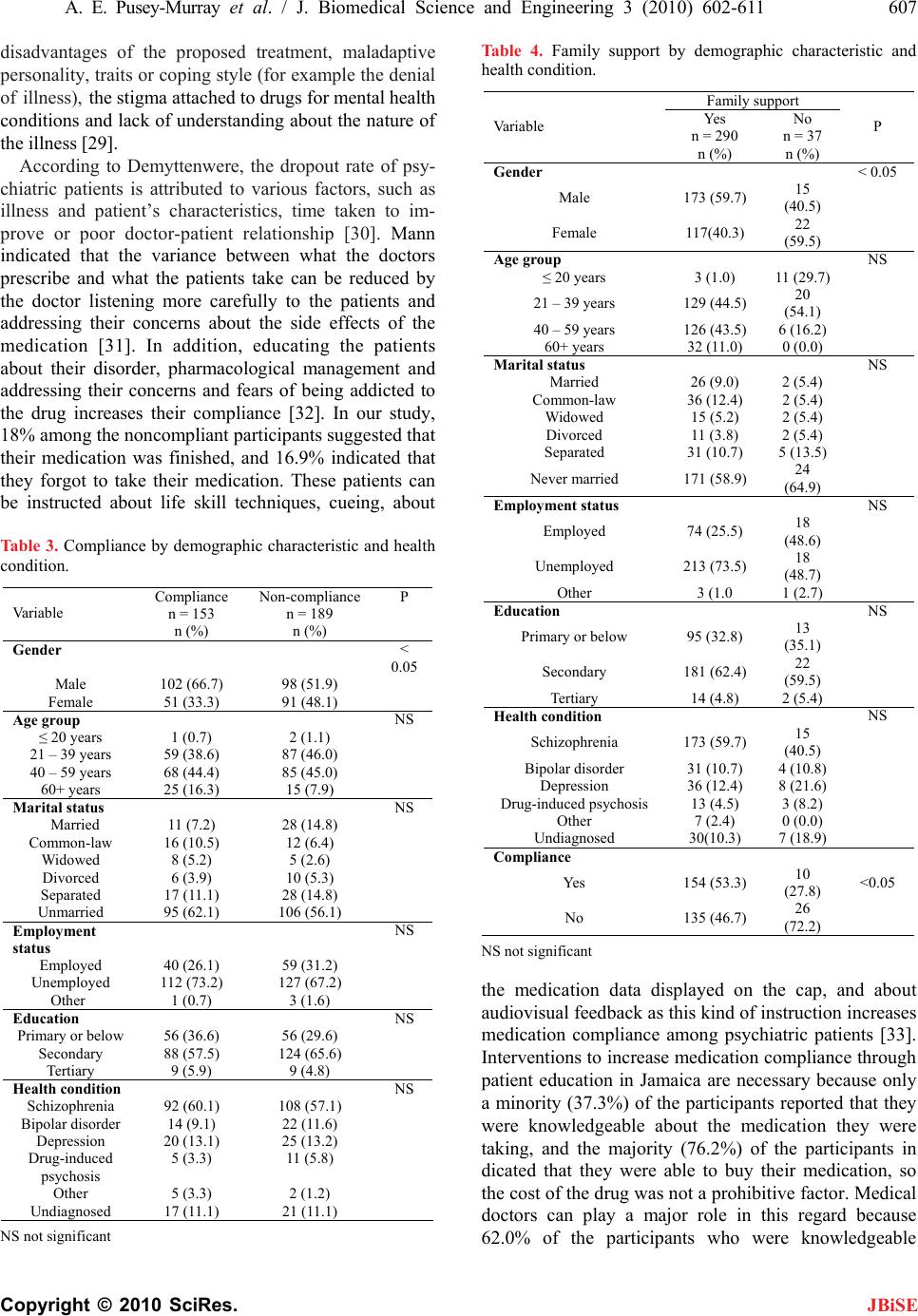

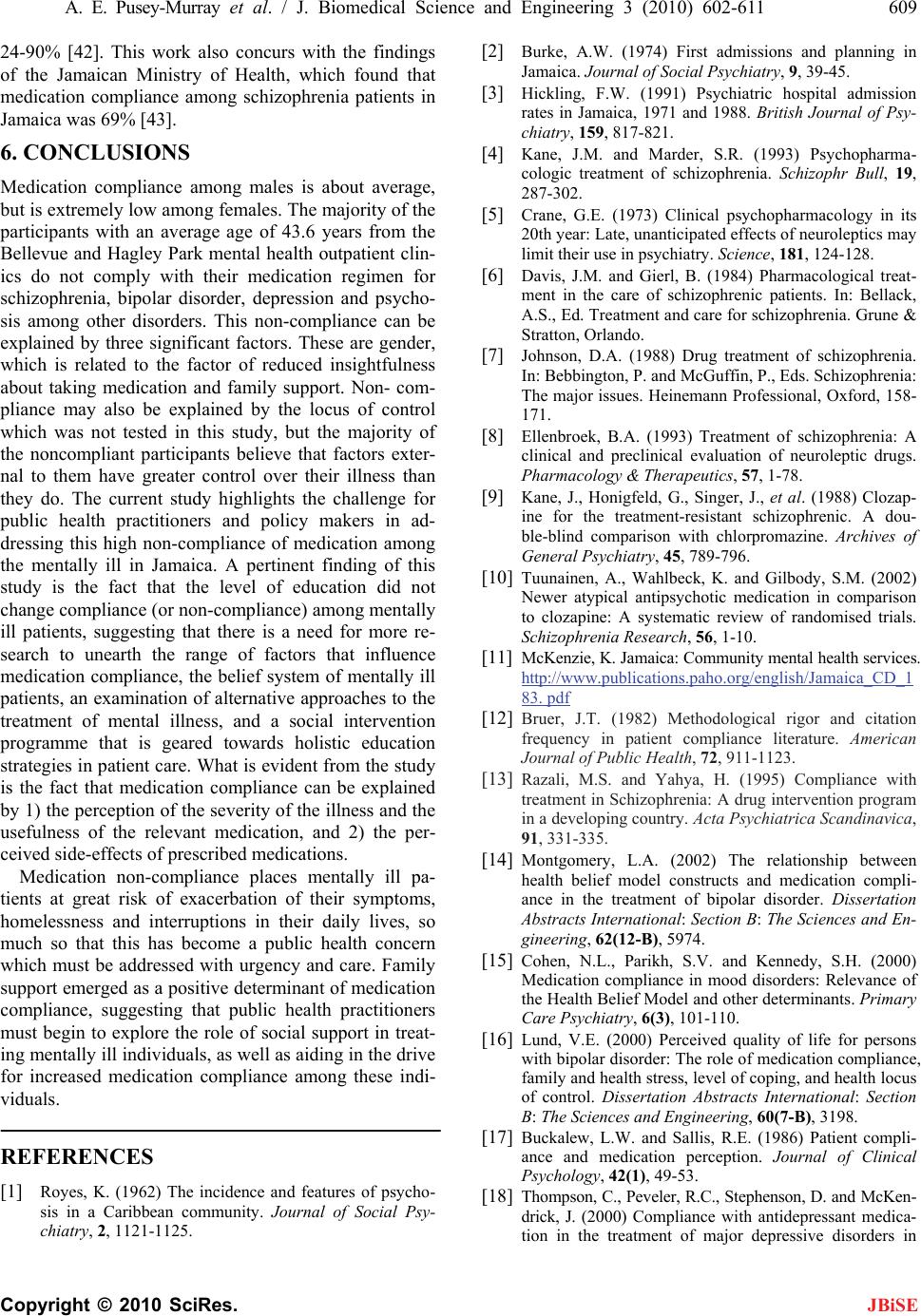

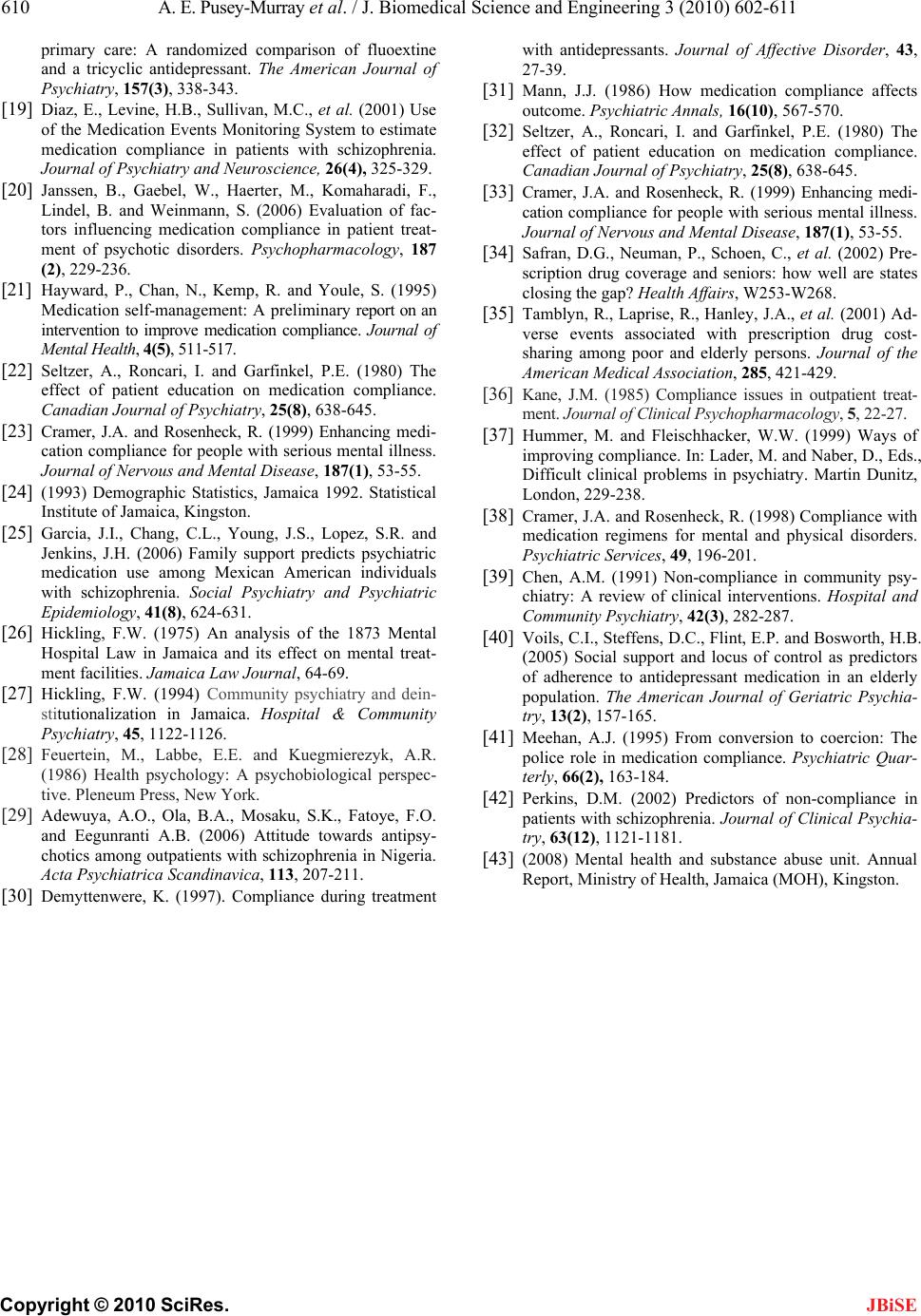

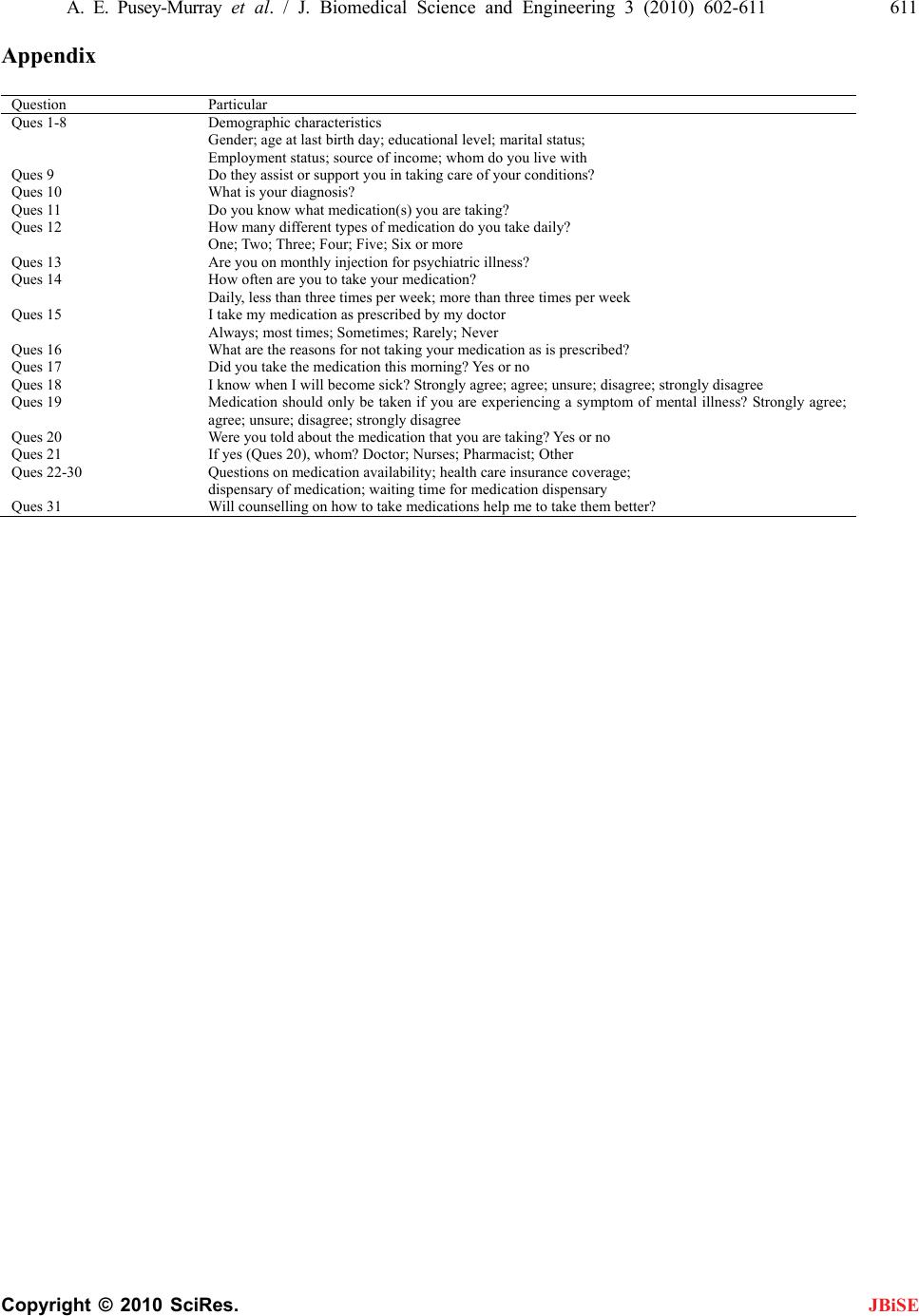

|