Creative Education 2012. Vol.3, No.3, 341-347 Published Online June 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2012.33054 Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 341 Using Story as Sites of Dialogue, Disillusionment, and Development of Dispositions to Support Inclusive Education Michelann Parr, Terry Campbell Schulich School of E ducation, Nipissing University, North Bay, Canada Email: {michelap, terryc}@nipissingu.ca Received April 10th, 2012; revised May 11th, 2012; accepted May 29th, 2012 This article reports on an ongoing action research project regarding stories and dialogue that can be used as experiences of difference and diversity, and their impact on the classroom environment/community and the teacher. Over a period of ten years, the researchers have engaged a total of 2400 teacher candidates, through their language and literacy course, in a discussion of what it means to be different and how these values and attitudes impact what happens in the classroom. Using children’s literature as a starting point, teacher candidates are encouraged to make connections between read alouds, reader response, critical lite- racy, and how this ultimately transforms their knowledge, values, and zones of comfort in both the teacher education classroom and the regular classroom. Keywords: Inclusive Education; Teacher Education; Story; Literature; Language and Literacy What Can We Do? Our Questions, Our Tensions Teacher candidates enter our classroom with varying levels of comfort with regard to individual difference, diversity, and equity. As are many teacher educators, we are often plagued by the question of “What can we do?” which not only suggests the vagueness of how we train teachers for diversity, but also the wonder of whether this is something that we can do within the context of a single course/program, given the assumptions, pre- dispositions (values and beliefs), and experiences of our teacher candidates (Garman, 2004; Pollock, Deckman, Mira, & Shalaby, 2010). Our teacher education program does not screen for what might be considered to be ideal teacher dispositions; acceptance into our program is based primarily on grades, with some space reserved for special populations. In fact, while we recognize the importance of prior dispositions and experiences, we feel that by critically examining such dispositions in relation to context, prior experience, and possible misperception, we can support our students in developing more positive attitudes and ideally essential teacher dispositions that will allow them to foster the core principles of inclusive education. We operate under the assumption that “an unexamined life is not worth living” (Plato) and that we can create environments that foster learning at the level of our learners, regardless of setting (UNESCO, 2009). It is our belief that in order to be truly effective as teacher educators, we must model and teach in a way that fosters and expects sensitivity and acceptance of difference and diversity. We discuss, at length, discourses or ways of being, reinforcing that every student brings a unique set of strengths, needs, prac- ti c es, and dispositions t o the classroom (Parr & Ca mpbell, 2007). Regardless of whether we align with the concept of “cultural capital” (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1977) , “funds of kn owledge” (Moll, Amanti, Neff, & Gonzalez, 1992), “ways with words” (Heath, 1983), or “discourses” (Gee, 2004, 2012), they all arrive at the same conclusion: “teaching students as opposed to teaching curriculum requires us to make our classrooms places where all students’ experiences and values are considered relevant, va- lued, and important” (Parr & Campbell, 2007: p. 80). Without explicit acceptance of these ways of being, we are overlooking a critical success point for many students. If we simply teach to the White middle class curriculum, we will have many students who are as excluded from the curriculum as they would be if they did not attend school at all. Transforming (that is, improving) attitudes and beliefs about diversity is not something that is easily accomplished. In fact, there have been studies (Haberman & Post, 1998; Levine-Rasky, 2001) that have gone so far as to suggest that teacher candidates should be screened upon entry based on their ideologies and predispositions, suggesting that diversity training is only useful for those who are open, self-aware, self-reflective, and com- mitted to social justice (Garman, 2004). We do not engage our students in diversity training; instead we continually ask our selves: “What can we do?” and “How can we provide experi- ences for our students that will enable them to explore, examine, and develop the dispositions needed to work with diverse populations?” In research into our own practice, as we search for answers to these questions, we are guided by the following practical ten- sions (Hollins & Guzman, 2005; Pollock, Deckman, Mira, & Shalaby, 2010): How do we encourage our teacher candidates to search for actionable steps that they can take in their own classrooms and schools? How do we, in our classes, encourage our teacher candi- dates to question the power of an individual educator to make a difference? How do we engage our teacher candidates in questioning  M. PARR, T. CAMPBELL their own personal readiness to become the type of educator who can successfully navigate issues of difference and di- versity in their own lives and classroom practice? Diversity, Equity, and Inclusive Education: Constructing a Disposition of Difference Transforming teacher candidates’ dispositions first requires us to examine what is meant by diversity, equity, and inclusive education, ultimately developing what Howard (2007) has re- ferred to what Howard (2007) has referred to as a disposition of difference. Because we teach elementary education in Ontario, our definitions are drawn from the Ontario Ministry of Educa- tion (2009) who defines the terms diversity, equity, and inclu- sive education in the following ways: Diversity: The presence of a wide range of human quali- ties and attributes within a group, organization, or society. The dimensions of diversity include, but are not limited to, ancestry, culture, ethnicity, gender, gender identity, language, physical and intellectual ability, race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, and socio-economic status. Equity: A condition or state of fair, inclusive, and re- spectful treatment of all people. Equity does not mean treating people the same without regard for individual differences. Inclusive Education: Education that is based on the prin- ciples of acceptance and inclusion of all students. Stu- dents see themselves reflected in their curriculum, their physical surroundings, and the broader environment, in which diversity is honoured and all individuals are re- spected (p. 4). Consistent with UNESCO (2009), our goal is “to eliminate exclusion that is a consequence of negative attitudes and a lack of response to diversity in race, economic status, social class, ethnicity, language, religion, gender, sexual orientation and abil- ity.” We recognize that “inclusive education is not a marginal issue but is central to the achievement of high quality education for all learners and the development of more inclusive societies. Inclusive education is essential to achieving social equity and is a constituent element of lifelong learning” (p. 4). But despite teacher awareness, acknowledgement of what is right and fair, and intent, inclusive education continues to be a philosophical and conceptual ideology and set of guidelines, as opposed to a way of being in many classrooms. This is not to say that we should not be aiming for the goals of inclusion, but that regardless of how we dialogue about diversity, equity, and inclusive educati on, we still have a long way to go. The challen- ge in education is not simply to be aware of the policies, but to find a way to put these ideologies into practice in a way that will “stimulate discussion, encourage positive attitudes, and impro- ve educational and social frameworks” (UNESCO, 2009: p. 7). We have found through our many encounters with teacher candidates that experiences of story and literature can stimulate discussion and allow students to examine their predispositions in a non-threatening environment. What follows is a description of how we initiate a dialogue of discourse with our teacher candidates and the types of discussions we have with them with regard to the use of story in our classrooms. Our hope is that they will in turn bring these texts into their own classrooms in relevant and sustainable ways. While we can aim for policy and guideline change, probably the greatest impact we will have, as teacher educators, is with individual teacher candidates. It is through these types of discussions that we hope to impress upon our teacher candidates that it is indeed possible for just one educator to make a difference. Our Context: Our Dispositions as Teacher Educators Between the two of us, we have 25 years teaching experience in elementary education. The philosophies and orientations to text that we bring to our teacher education classrooms are largely shaped by our encounters with literature and children in the field. About inclusion, individual difference, and the need for ongoing discussion and experience, they have taught us much. Today, we teach a combined 240 teacher candidates through our language and literacy course every year, meaning that over the past ten years, we have had these conversations with close to 2400 students, many of whom accept jobs in in- ternational settings. Our course runs for 66 hours over two se- mesters; we encounter the students bi-weekly for two hours each, allowing us time to read, respond, discuss, and experience how children’s literature can make a difference in our lives and those of our students. As teachers of language and literacy, we do feel that it is not solely the role of the Multicultural Education, Special Educa- tion, or Educational Psychology courses to discuss issues re- lated to diversity. Hence, we weave discussions and experi- ences of diversity into our classroom discussions and activities on a daily basis. We accept our role in exploring, examining, and furthering attitudes and beliefs about diversity—we insist that diversity and individual differences are something to be celebrated and embrac ed as opposed to to l erated an d excluded. We do, however, find it difficult at times, in a predominantly White middle class, female, teacher education program to get across the impact of diversity as it is reflected in ways of being in the world that are not simply difference as a firm grasp of the obvious (e.g., race, gender, religious affiliation). Over our ten years of teaching in teacher education, we have found that story can provide our students with critical cultural experiences that allow them to explore their own ways of being in the world and talk about them in supportive and non-threatening environ- ments, always in an effort to understand their students and their diverse ways of being. Our goal, like Howard (2007), is to encourage, explore, and facilitate the development of the following teacher dispositions: A disposition for difference: teachers who are culturally competent and comfortable in their own skins, and able to negotiate effectively across multiple dimensions of differ- ence; A disposition for dialogue: teachers who embody, and mo- del for students, the capacity to engage in conversation rather than wage war across differences; A disposition for disillusionment: teachers who look be- yond the barriers of their own culturally conditioned reali- ties, ultimately allowing themselves to become disillusioned with assumptions, perceptions, and misperceptions; A disposition for democracy: teachers who challenge the dynamic of dominance and work to give their students a fair and equitable chance of success in life. Stories as Exploration and Encounter: New Places, New People, New Ideas Stories are powerful. They are a journey and a joining. In a Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 342  M. PARR, T. CAMPBELL tale we meet new places, new people, new ideas. And they be- come our places, our people, our ideas. —Jane Yolen Story is one way that we can stimulate conversations among students, teachers, families, even communities. We can exa- mine critically what is happening in narrative literature in an effort to understand what is happening in our worlds. We can expose ourselves to different worlds and different places that allow us to think differently, being mindful of our ways of be- ing in the world as well as the needs of others. And through story, we can encourage our teacher candidates to think, ulti- mately putting the world, as they know it, in jeopardy (Dewey). In order for us to stimulate these types of discussions, we must first ensure that we are selecting stories that are accessible and relevant to the lives of our learners. We do not shy away from provocative or “risky” literature as this is where we often see the most dissonance and then the greatest shift in awareness. We feel strongly that many teacher candidates need to be nudged away from the assumption that children’s books are meant to be cute, entertaining, and light, and that children’s books should always be happy and make us all feel better. Life is not always pretty, so why do we expect stories to be? We do not espouse stories that are cynical and despairing, but neither do we avoid texts with strong issues that make us think and give us something worth talking about. In order to find stories that stimulate deep discussion, we look first of all for a text that is well-written. This means it needs to tell a good story that takes place in an authentic setting, has characters who are con- vincingly real, is told with a unique style, and is presented in an appealing format (for example, the illustrations enhance the story, the book is an appropriate size and shape, and has well- designed pages and typography). In addition, the overarching theme that gives rise to conversation about important issues is integrated into the story seamlessly rather than appearing as an overly moralistic lesson. Story allows us to establish the issues, discuss them, and then come up with a way to address them. Envisioning story as a cultural space and experience allows us to move beyond “talk- ing about diversity” to experiencing diversity. Students engage in dramatization of stories, debate among characters, journaling, walking around inside a character’s head to get at the heart of their thinking and response to situations, things that cannot wait until they are in the midst of a real life experience. Story can provide teacher candidates with an opportunity to plan and rehearse issues and scenarios they might encounter some day with real students. Further, through story, teacher candidates can try on a stance, examine it, and reflect upon it, all of which are critical dispositions when working with students, particu- larly diverse populations. Stories as Interrogative and Critical Spaces: Our Places, Our People, Our Ide as Be patient with all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves like locked rooms and like books written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek the answers which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then, gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer. —Rainer Maria Rilke I believe that good questions are more important than an- swers, and the best children’s books ask questions and make the readers ask questions. And every new question is going to disturb someone’s universe. —Madeline L’Engle The stories we describe below are offered as spaces that allow us to explore, examine, discuss, and revise what is meant by difference, diversity, equity, and inclusive education in our classrooms. We know that our concept of self as a literate being shapes who we are in the classroom and how we interact with our students. By juxtaposing our own stories with children’s books, we can try to “understand what happened and why” (Meyer, 1996: p. 1). These new stories, the ones that come to be at the intersection of personal self and story can become, if we allow them, a kind of primary text in classes, enabling us to uncover our unspoken assumptions; examine the contradictions between our pedagogies and our experiences; complicate our understandings of literacy, learning, and teaching; integrate our examined experiences into our working conceptions of literacy and learning; develop intimacy and build community. They also provide us with a sense of our own authority to resist and revise the powerful culture of schools (Wilson & Ritchie, 1994: p. 85). Each time we return to a story or introduce a new one, we anticipate great discussion, we expect some resistance and some disillusionment, and we know that each new question will disturb someone’s universe, but we hope that our students will be patient and travel their way gradually toward the answers. We know that without this dissonance, it is unlikely that our students will step outside their own perspectives and views to consider those different than their own. We know, though, that in order to be truly effective in diverse classrooms, teacher candidates must understand, with sensitivity and respect, who they are and how that influences their relationships with stu- dents. Further, it means “being open to the voices in books” developing critical insights, and moving toward “the goal of creating classrooms that uncover the hidden possibilities for our students” (Meyer, 1996: p. 129). Classroom Communities as Storied Spaces: Our Principles, Our Experiences Our literature set reflects texts that foster different ways of thinking and being, different ways of seeing the world, and different ways of acting and reacting (see Table 1). The stories we describe below are a starting point only. The challenge for us lies in how we present and discuss the identified themes with students. Ultimately, what works best is what gets them talking, digging beyond the surface, and eventually navigating their selves, their students, their communities, and their worlds. It is our belief that teachers who have these sorts of stories at their fingertips can use them when relevant to disrupt the realities and universes of their students in a positive way. We apply the following guidelines to ensure that our encounters with litera- ture become storied experiences: Introduce the story: Talk about concepts to establish a pur- pose for listening; ask for expectations or make connections to the title or book cover. Read aloud for pleasure, interrupting the story only when it is relevant to the overall experience (e.g., getting students to think like a character or picture themselves in a given situa- tion). Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 343  M. PARR, T. CAMPBELL Table 1. Children’s literature that fosters storied experiences (starred titles are highlighted below). Community, risk taking, and collaboration The Dot and Ish by Peter Re y nolds Scaredy Squirrel by Mélanie Watt Stone Soup by Jon J. Mu th The Three Questions by Jon J. Muth* Bullying Hooway for Wodney W at by Helen Lester* Don’t Laugh at Me by S t eve Seskin and Allen Shamblin Chrysanthemum by Kevin Henkes One by Kathryn O toshi Learning differences Frederick by Leo Lionni* Crow Boy by Taro Yashima* The Junkyard Wonders by Patricia Polacco* Through the Cracks by Carolyn Solomon Thank You, Mr. Falker by Patricia Polacco Race and c ult ural diver si ty Nokum is my Teacher by David Bouchard* All the Colors of the Earth by Sheila Hama naka Skin Again by bell hooks Am I a Color Too? by Heidi Cole and Nancy Vogl Language d if ferences and arrival in a new country Marianthe’s Story: Painted Words and Spoken Memories by Aliki* The Name Jar by Yangsook Choi Angel Child, Dragon Child by Michele Maria Surat The Arrival by Shaun Tan Emotional differences Michael Rosen’s Sad Book by Michael Rosen* Through the Forest by Anthony Browne Jenny Ange l b y Eve Bunting Monster Mama by Liz Rose n berg Woolvs in the Sitee by Margaret Wild Socio-economic diversity The Hundred D resses by Eleanor Estes* Voices in the Park by Anthony Browne Fly Away Home by Eve Bunting Those Shoes by Maribeth Boelts The Can Man by Laura E. Williams and Greg O rman Religious di versity Old Turtle by Douglas Wood* Winter Lights: A Season in Poems and Quilt s by Anna Grossnickle Hines Global awareness Four Feet, Two Sandals by Karen Lynn Williams & Khandra Mohammad Galimoto by Karen Lynn Williams The Orphan Boy by Tololwa M ollel The Compos i tion by Antonio Skarmeta All Kinds of Children by Norman Simon Amazing Grace by Mary Hoffman Making it Home: Real-life Stories from Children Forced to Flee by Beverly Nadoo After reading, discuss the me ssage s/theme s teacher candidate s hear in the story, the connections they make, and reflections on how they can apply the stories to their own lives. Extend the reading by discussing how these stories can be experienced in the classroom with students of all ages in order to build community, teach principles of inclusive education and inclusive societies, ultimately fostering glo- bal awareness (see Table 2). Building a Community that Fosters Risk-Taking and Collaboration Principle 1: All students have a right to be valued, contribu- ting members in our classroom community. Frederick by Leo Lionni, is a timeless tale about field mice who work to gather food and supplies that will help their com- munity weather the long, harsh winter. They work day and night, all except Frederick who appears to be dreaming. When queried by his comrades, however, he suggests that he is gath- ering supplies—colours for the winters are long and gray, sto- ries for we’ll run out of things to say, and words that will transform realities. Readers are asked to be patient, to suspend judgment, and then to decide whether Frederick’s supplies are as worthy as his peers. In a room of teacher candidates, the opinions are varied. Many see his value as critical to the well- being of the community, many are indifferent, and many feel that he’s lazy and not offering anything of substance to the community. In fact, in dramatizing the story one year, a group of teacher candidates voted Frederick off the island indicating that, “his contribution of colours, stories, and words were not enough to balance his consumption of food and supplies.” Those who do see the value of Frederick’s contributions re- cognize the less concrete, but nonetheless essential value of artistic and creative expression—in this case, poetry. The text allows us to discuss the nature of contribution and comfort to be who you are in a community, without an expectation of con- formity. Coping with Bullying Principle 2: All students have a right to feel included and Table 2. Principles of inclusive education fostered by storied experiences. 1) All students have a right to be valued, contributing members in our classroom. 2) All students have a right to feel included and welcome in our classroom community. 3) All students have a right to feel th at they have something unique to offer. 4) All students have a right to bring their culture to school every day. 5) All students have a right to a right to speak a n d be heard, regardless of the language they use. 6) All students have a right to “just be” in our classroom without feeling excluded as a result. 7) All students have a right to empathy and understanding and protection against all forms of cruelty in our classrooms. 8) All students have a right to express and live their spiritual beliefs. 9) All students who need it have a right to special education and individualized programming without feeling excluded. 10) All students should consider needs, wants, and rights different than their own. Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 344  M. PARR, T. CAMPBELL welcome in our classroom community. Hooway for Wodney Wat by Helen Lester recounts an inter- esting tale of being bullied and bullying. Wodney is a rat who struggles to pronounce the letter r; as a result, he is the victim of teasing and bullying. In the end though, when a new rodent enters the scene and starts to bully the bullies, Wodney’s di- fference transforms him into a hero. Throughout our program, students discuss the issue of bullying in the classroom, on the schoolyard, even cyberbullying, always from a theoretical, “talk about it” stance. But one year, we found that one of our cohorts (groups of forty students) was knee deep into a bullying situa- tion and few of them even recognized it. Here, we chose our literature wisely, looking for a text that would allow us to “talk about the issue” but also to allow students to experience it from a character’s perspective, thus providing a hypothetical situa- tion that would allow us, and them, to discuss bullying and the various roles played by those involved. Following a read aloud, teacher candidates were asked to re- enact the story, focusing on relating to characters and walking around inside their heads to get an idea of what they were thinking (Clyde, 2003). In the end, this text allowed teacher candidates to step back from their cohort experience and exam- ine their personal biases, behaviours, and perspectives—all of which suggest that storied experiences enable us to see the fa- miliar and the experienced in dif ferent ways. Acknowledging Our Right to Learn Differently Principle 3: All students have a right to feel that they are a valued member of the community with something unique to offer. Crow Boy by Taro Yashima tells the story of a boy nick- named “Chibi” (small boy). At school, he is an academic and social outcast. The narrator of the story—an anonymous class- mate—describes Chibi as being unable to learn a thing or to make friends with the other children. He was “left alone in the study time… left alone in the play time… always at the end of the line… a forlorn little tag-along.” This story evokes a range of responses from teacher candi- dates. Some state initially that they don’t like the book. They think it is too strange, and that children will not like it. Some are able to identify with the character of Crow Boy; others are able to empathize with his isolation due to his difference from the other children. Upon discussion and after revisiting the story, some of those who initially disliked the book extend their opinions, recognizing the value of the story “because we have all known Crow Boys, and will probably encounter Crow Boys in our future classrooms.” Valuing Race and Cultural Diversity Principle 4: All students have a right to and bring their cul- ture to school each and every day. In Nokum is My Teacher by David Bouchard, a young boy questions his grandmother, his Nokum, about life beyond their reserve and beyond school. He wonders about his displacement into the “White man’s world” and why it is that he has to learn their way and their things in their way. Really what he is inter- rogating is a fundamental issue faced by many students—Why is the learning at school valued more than the learning outside of school? Who made these decisions? The story allows us a glimpse into the thoughts of a student who has not yet discovered his place in a world that he consid- ers foreign and unfamiliar. The questions he asks are critical for our teacher candidates to consider. How will they accommodate these students in their classrooms? How will they help them to belong, and most importantly, how will they help them to bring their culture and their home literacies into the classroom? Our discussions with teacher candidates often circle around the con- cept of teaching students first and curriculum second, helping teacher candidates to realize that in order to teach curriculum, they must indeed see and understand their students first and then make the curriculum meaningful and relevant to their lives both in and out of school. Working with Language Differences and Arrival in a New Country Principle 5: All students have a right to speak and be heard, regardless of the language they use. Marianthe’s Story: Painted Words and Spoken Memories by Aliki is based on the author’s own experiences emigrating to the United States from Greece and attending school with very little English. The story is told through the voice a young girl, Mari. She is apprehensive on her first day in a new school, but her mother assures her that she will be able to “look, and listen, and learn” and that “a smile is a smile in any language.” In her classroom, Mari expresses herself and tells her story through painting. This story almost always elicits an emotional reaction from adult listeners in our university classroom, especially in those who are immigrants or chil dren of immigrants. Beyond that, they all recognize the potential of this text to stimulate discussion among children and to lead to awareness of multiple perspectives. For children, this story in our experi- ence is usually taken at face value. If they have not experienced speaking a different language from those around them, they understand what it is like to be the “new kid” in various situa- tions. From there, they can extrapolate to the experience of being unable to speak the dominant language in a new group. Respecting Emotional Differences Principle 6: All students have a right to “just be” in our classroom without feeling excluded as a result. Michael Rosen’s Sad Book by Michael Rosen (illustrated by Quentin Blake) opens with a drawing of a smiling face, under which it says, “This is me being sad.” The author explains that he is really sad but pretending to be happy because he thinks people won’t like him if he looks sad. The book goes on to explore the feelings of sadness; including when they become so overwhelming he can no longer pretend. “Sometimes sad is very big,” he says, and the drawing above is grey and brown, with a very small figure walking with hunched shoulders. We learn that he is sad because his son Eddie died (even though he really loved him). Then he remembers things like laughter, playing together, and candles on birthday cakes. The text ends without words, just a picture of the author contemplating a brightly lit candle. Teacher candidates recognize the importance of addressing real life issues such as death and sadness, but many worry about the possibility of bad timing—what if a child in the classroom has recently experienced a death in their family? Wouldn’t a text like this one be too painful? We have deep discussions about this issue. Most conclude that it is crucial to know your students, and that it is always a judgment call. During discus- sion, we consider the opinions of well-known authors on the subject of death. Katherine Paterson, the author of Bridge to Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 345  M. PARR, T. CAMPBELL Terabithia for example, said that there is no perfect time to discuss the reality of death, and that if we leave it until a death has occurred it is too late (Paterson, 1989). Appreciating Socio-Economic Diversity Principle 7: All students have a right to empathy and under- standing and protection against all forms of cruelty in our classrooms. Eleanor Estes’ (1944) The Hundred Dresses is a children’s “classic” which continues to resonate for many school children. In this story a group of schoolgirls, including a popular leader and an increasingly conscience-stricken bystander who goes along with them, taunt Wanda Petronski. Wanda lives “up on Boggins Heights, which was no place to live” and “always wore the same faded blue dress that didn’t hang right.” Every- day as she’d make her way to school, the girls would ask Wanda how many dresses she had to which she would respond that she had one hundred dresses hanging up at home. The girls’ merciless teasing eventually causes the family to leave town. The girls realize what they have done by the end, but, as one grade four student once remarked, “It’s horrible, cause they can’t do anything about it.” This story is particularly troubling in a beneficial, thought-provoking way, since it offers no tidy solution. This is the sort of story that students do not forget; it can be a touchstone when related topics or situations arise. While most teache r candidates have not encountered this story, they comment that it is still realistic after all these years and certainly a situation they feel they will encounter at some point in their teacher careers. The story itself offers multiple oppor- tunities for discussion—what it means to bully, the impact of socioeconomic status, the resilience of a human spirit, etc. Embracing Religious Diversity Principle 8: All students have a right to express and live their spiritual beliefs. Old Turtle, written in poetic parable style by Douglas Wood, with gorgeous watercolour illustrations by Cheng-Khee Chee, explores the meaning(s) of God from the point of view of vari- ous creatures and natural beings from rocks, stars, and trees to fish, birds, and mammals. As their choruses escalate into a loud argument, wise Old Turtle speaks up, to eloquently express how God is. He goes on to tell about the immanent coming of a “new family of beings,” who naturally must learn the same truths about love and “the beauty of all the earth.” Whether or not teachers find themselves in a school setting where religion is openly practiced and taught, this book shows us how we can address spiritual truths in a secular way. This book can stimulate profound discussions about the wonders of nature, the place of human beings on this earth, and yes, about the nature (and existence) of God. Reading this book to our teacher candidates often evokes a range of reactions, particu- larly to the use of the word God throughout and whether this is appropriate in all school settings. They take it quite literally and often assume that Wood is referring to a specific God instead of many. Many teacher candidates can see the value in such a story but readily agree that they would substitute the word God with a non-spiritual term that would reduce the risk associated with privileging one religion over another. It’s interesting to hear year after year the same reaction, despite increasing mul- ticulturalism. It seems that instead of bringing more diversity in terms of religion into a classroom (which is beautifully pre- sented in Old Turtle), we are more content to shelf stories that have spiritual themes. Including Learning Differences in Meaningful Ways Principle 9: All students who need it have a right to special education and treatment without feeling excluded. In The Junkyard Wonders, Patricia Polacco writes and draws from her personal experiences growing up with dyslexia and struggling in school with reading, math, and being teased until she encountered a teacher who “changed her life” by helping her realize her inner genius. The junkyard wonders are an “oddly brilliant group of misfit kids” who have been excluded from “regular classes” and placed into a “special” class. It is into this “special class” that the book’s central character, Trish, is placed when she attends a new school. Teacher candidates invariably find this story moving and in- structive about what it can be like to be labeled or categorized and how very important it is to discover and capitalize on the strengths of their students. Despite the “special” class, Mrs. Peterson created an inclusive environment, one that valued and welcomed individual differences, and ensured that each stu- dents found something meaningful and authentic in the cur- riculum. She ignited in her students the love of learning and appreciation of the diverse wonders of each student. Ultimately, The Junkyard Wonders also celebrates the profound difference that a single caring and informed teacher can make in the lives of students like Trish. And while they realize that it will not be easy, and that they will indeed struggle along the way, they also realize that it is possible. Developing Global Awareness—Learning about Self in Relation to the World Principle 10: All students should consider needs, wants, and rights different than their own. Four Feet, Two Sandals, by Karen Lynn Williams and Khadra Mohammed is a story about two young girls in a refu- gee camp set somewhere in the Middle East. When workers drop off clothing for the refugees, each girl takes one sandal from the pile only to discover that the matching one belongs to another girl. They are able to work out a way to share the san- dal and as a result of their interaction, develop a friendship. Against a backdrop of surviving war and living in extreme dif- ficulty, the young girls discover a humanity in each other. Ac- cording to one teacher candidate, “The stunning images evoke so much emotion that readers are able to sense what the main characters are feeling without reading the words.” Responses to this story are invariably emotional. Upon re- flection, discussants in our education classrooms conclude that this is a strong text that can help to address awareness of global issues and what war means on the individual, human level: “As parents and educators, we often think that young children are not able to see and process controversial global issues and should be shielded from them. This book offers an opportunity to explore the idea of a refugee camp through a story that has a resolved ending.” Stories as Inclusive and Reconciling Spaces: Our Practices, Our Visions, Our Transformed Attitudes Here we return full circle back to our initial question. What can we do? We finish the year with The Three Questions by Jon Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 346  M. PARR, T. CAMPBELL Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 347 J. Muth, a children’s storybook based on Tolstoy’s The Blind Men and the Elephant. In this story, a little boy is puzzled with what he feels are three very important questions: “When is the best time to do things? Who is the most important one? What is the right thing to do?” He searches out the answers among his friends, finding no satisfaction. He decides to visit Leo, the very wise turtle, to see if he can answer his questions, but alas, finds himself first digging a garden and then saving a panda and her child. In the end, the boy is presented with the following lesson: Remember then that there is only one important time, and that time is now. The most important one is always the one you are with. And the most important thing is to do good for the one who is standing at your side (Muth, 2002). Ultimately, through all the work we do with our teacher can- didates, this unifying principle is the most critical. We want them to know that what is right, and what is fair, is ensuring that all students have a fair and just chance to succeed. This means that teachers must have the tools to foster the principles for inclusion we have cited above, recognizing that this does not mean that every single student is treated the same way; on the contrary, it means that all students’ differences are cele- brated. The stories we have described above show how this can happen, and also what happens when we ignore the differences. Through stories such as these, we help our teacher candidates to see that inclusive education is not about physically including students in classrooms or buildings, but is instead about making them feel welcome and valued members of a classroom com- munity. Storied experience enables us to open the doors to the de- velopment of the dispositions of difference, dialogue, disillu- sionment, and democracy, dispositions that will continue to develop through ongoing dialogue with students in the class- room. These insights and dispositions are crucial for contem- porary classroom teachers in inclusive environments. Stories such as these encourage us to adopt multiple perspectives and understandings, so that places, people, and ideas that were once new and unfamiliar become our places, our people, our ideas. REFERENCES Aliki (1996). Marianthe’s story: Painted words and spoken memories. New York: Harper Collins Children’s. Bouchard, D. (2006). Nokum is my teacher. Tor ont o, ON: R ed De er Pr ess. Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J. C. (1977). Reproduction in education, society, and culture. London : Sa g e . Clyde, J. A. (2003). Stepping inside the story world: The subtext strate- gy—A tool for connecting and comprehending. The Reading Teacher, 57, 150-160. Estes, E. (1944). The hundred dresses. Boston, MA: Harcourt Inc. Garmon, M. A. (2004). Changing preservice teachers’ attitudes/beliefs about diversity: What are the critical factors? Journal of Teacher Edu- cation, 55, 201-213. doi:10.1177/0022487104263080 Gee, J. P. (2004). Situated language and learning: A critique of tradi- tional schooling. New York: Routledge. Gee, J. P. (2012). Social linguistics and literacy: Ideology in discourses. New York: Routledge. Hab er man, M., & Post, L. (1998). Teacher for multicultural schools: The power of selection. Theory into Practice, 17, 96-104. doi:10.1080/00405849809543792 Heath, S. B. (1983). Ways with words: Language, life, and work in commu- nities and classrooms. New York: Cambridge University Press. Hollins, E., & Guzman, M. T. (2005). Research on preparing teachers for diverse populations. In M. Cochran-Smith, & K. M. Zeichner (Eds.), Studying teacher education: The report of the AERA panel on research and teacher education (pp. 477-548). Mahwah, NJ: Law- rence Erlbaum. Howard, G. (2007). Dispositions for good teaching. URL (last checked 29 March 2012). http://www.wce.wwu.edu/Resources/CEP/eJournal/v002n002/a009.s html Lester, H. (2002). Hooway for wodney wat. Boston, MA: Houghton Mi- fflin Harcourt. Levine-Rasky, C. (2001). Identifying the prospective multi-cultural edu- cator: Three signposts, three portraits. Urban Review, 33, 291-319. doi:10.1023/A:1012244313210 Lionni, L. (1973). Frederick. New York: Random House. Meyer, R. J. (1996). Stories from the heart: Teachers and students re- searching their literacy lives. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Moll, L. C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & Gonzalez, N. (1992). Funds of know- ledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory into Practice, 31, 132-141. doi:10.1080/00405849209543534 Muth, J. J. (2002). The three questions. New York: Scholastic. Ontario Ministry of Education (2009). The equity and inclusive educa- tion strategy. Toronto, ON: Que en ’s Press for Ontario. Parr, M., & Campbell, T. (2007). Teaching the language arts: Engag- ing literacy practices. Toronto, O N : John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Paterson, K. (1989). The spying heart: More thoughts on reading and writing books for childr e n . New York: E. P. Dutton. Polacco, P. (2010). The junkyard wonders. N e w Yor k: P hi l omel Books. Pollock, M., Deckman, S., Mira, M., & Shalaby, C. (2010). “But what can I do?”: Three necessary tensions in teaching teachers about race. Journal of Teacher Educat i o n, 61, 211-224. doi:10.1177/0022487109354089 Rosen, M. (2005). Michael Rosen’s sad book. Somerville, MA: Candle- wick Press. UNESC O (2009). Policy guidelines on inclusion in education. UR L (last checked 16 March 2012). unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0017/001778/177849e.pdf Williams, K. L., & Mohammed, K. (2007) . Four feet, two sandals. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdm ans Publishing Co. Wilson, D. E., & Ritchie, J. S. (1994). Resistance, revision, and repre- sentation: Narrative in teacher education. English Education, 26, 177- 188. Wood, D. (1992). Old turtle. New York: Scholastic. Yashima, T. (1976). Crow boy. New York: Pen guin Group.

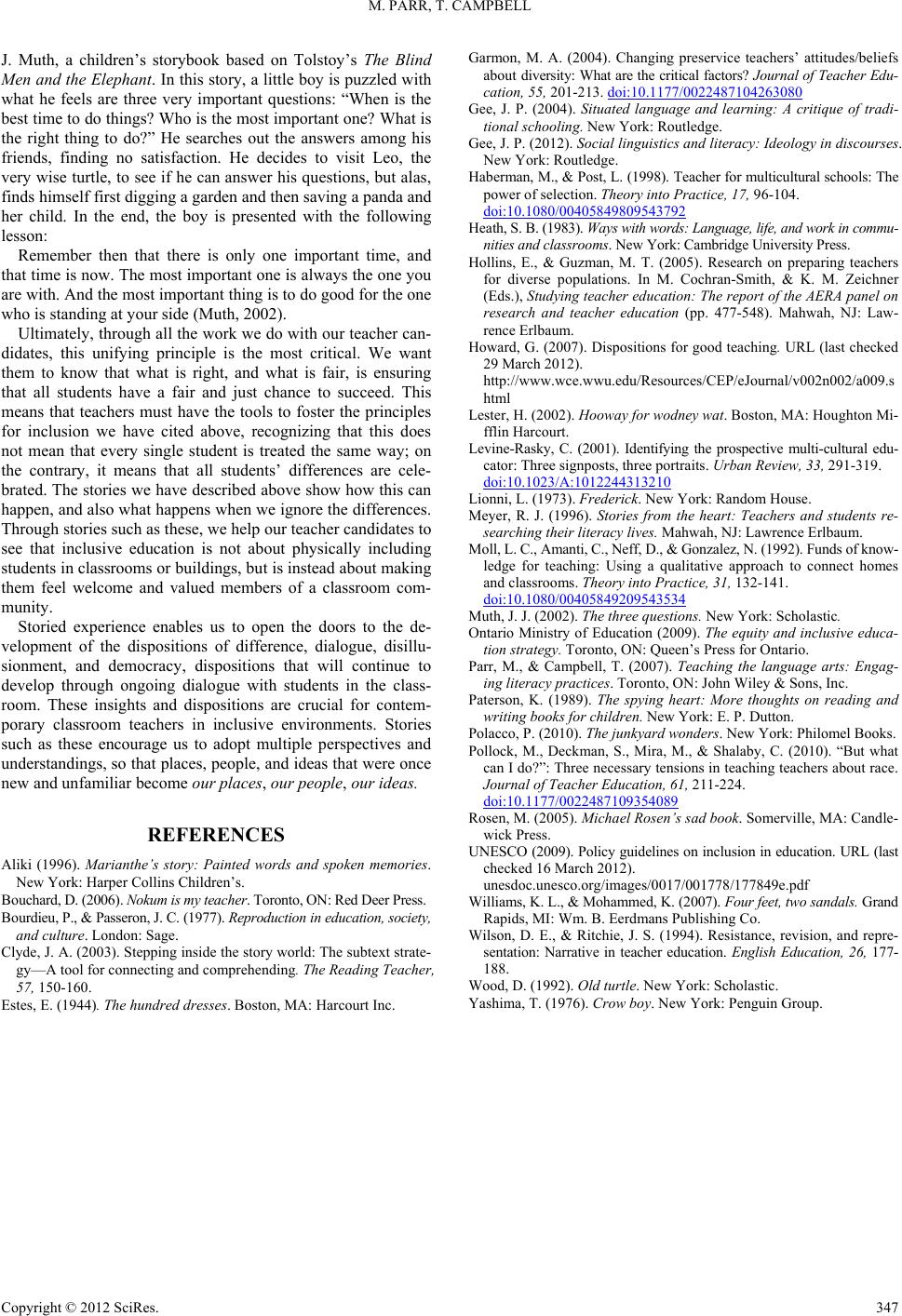

|