E. C. HURLEY ET AL.

RDAS scores were negatively correlated with the ARSQ scores

(r = –.52), the number of military deployment separations (r =

–.27) and the total time separated (r = –.20). Higher rejection

sensitivity scores, more deployment separations and the total

time separated were associated with lower marital adjustment

scores.

The extent to which the zero-order negative correlation be-

tween the composite ARSQ and RDAS scores (r = –.52) was

influenced by the potentially confounding/mediating variables

was determined by partial correlation analysis. None of the par-

tial correlation coefficients decreased when the correlation be-

tween ARSQ and RDAS was controlled for gender, age, educa-

tion, times married, current marriage length, times spouse mar-

ried, number of children, average child age, deployment separa-

tions, other separations, total time separated, or current separa-

tion time. Thus, the negative correlation between ARSQ and

RDAS was not mediated by the potentially confounding vari-

ables.

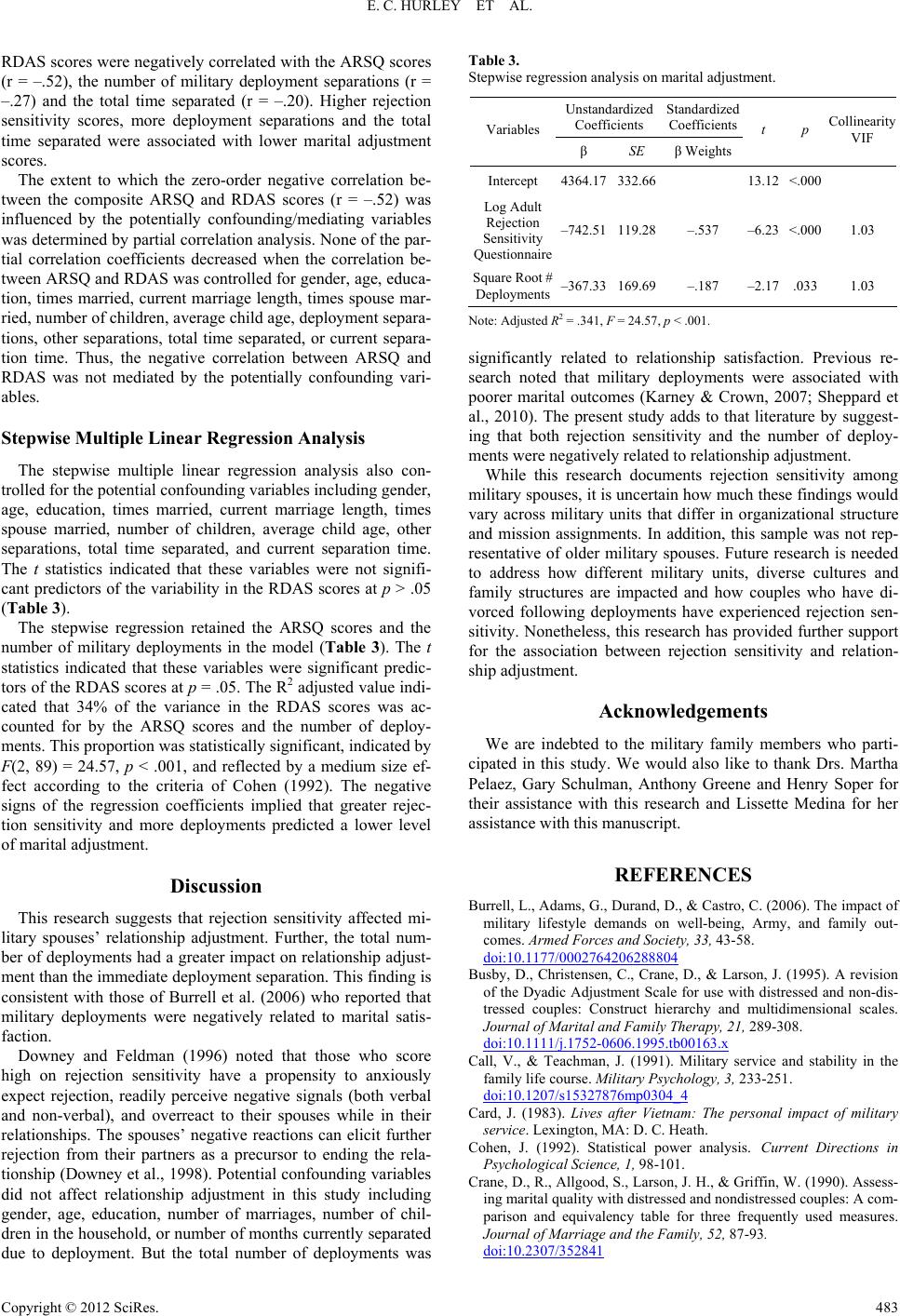

Stepwise Multiple Linear Regression Analysis

The stepwise multiple linear regression analysis also con-

trolled for the potential confounding variables including gender,

age, education, times married, current marriage length, times

spouse married, number of children, average child age, other

separations, total time separated, and current separation time.

The t statistics indicated that these variables were not signifi-

cant predictors of the variability in the RDAS scores at p > .05

(Table 3).

The stepwise regression retained the ARSQ scores and the

number of military deployments in the model (Table 3). The t

statistics indicated that these variables were significant predic-

tors of the RDAS scores at p = .05. The R2 adjusted value indi-

cated that 34% of the variance in the RDAS scores was ac-

counted for by the ARSQ scores and the number of deploy-

ments. This proportion was statistically significant, indicated by

F(2, 89) = 24.57, p < .001, and reflected by a medium size ef-

fect according to the criteria of Cohen (1992). The negative

signs of the regression coefficients implied that greater rejec-

tion sensitivity and more deployments predicted a lower level

of marital adjustment.

Discussion

This research suggests that rejection sensitivity affected mi-

litary spouses’ relationship adjustment. Further, the total num-

ber of deployments had a greater impact on relationship adjust-

ment than the immediate deployment separation. This finding is

consistent with those of Burrell et al. (2006) who reported that

military deployments were negatively related to marital satis-

faction.

Downey and Feldman (1996) noted that those who score

high on rejection sensitivity have a propensity to anxiously

expect rejection, readily perceive negative signals (both verbal

and non-verbal), and overreact to their spouses while in their

relationships. The spouses’ negative reactions can elicit further

rejection from their partners as a precursor to ending the rela-

tionship (Downey et al., 1998). Potential confounding variables

did not affect relationship adjustment in this study including

gender, age, education, number of marriages, number of chil-

dren in the household, or number of months currently separated

due to deployment. But the total number of deployments was

Table 3.

Stepwise regression analysis on marital adjustment.

Unstandardized

Coefficients

Standardized

Coefficients

Variables

β SE β Weights

t p

Collinearity

VIF

Intercept 4364.17332.66 13.12 <.000

Log Adult

Rejection

Sensitivity

Questionnaire

–742.51119.28–.537 –6.23 <.000 1.03

Square Root #

Deployments–367.33169.69–.187 –2.17 .0331.03

Note: Adjusted R2 = .341, F = 24.57, p < .001.

significantly related to relationship satisfaction. Previous re-

search noted that military deployments were associated with

poorer marital outcomes (Karney & Crown, 2007; Sheppard et

al., 2010). The present study adds to that literature by suggest-

ing that both rejection sensitivity and the number of deploy-

ments were negatively related to relationship adjustment.

While this research documents rejection sensitivity among

military spouses, it is uncertain how much these findings would

vary across military units that differ in organizational structure

and mission assignments. In addition, this sample was not rep-

resentative of older military spouses. Future research is needed

to address how different military units, diverse cultures and

family structures are impacted and how couples who have di-

vorced following deployments have experienced rejection sen-

sitivity. Nonetheless, this research has provided further support

for the association between rejection sensitivity and relation-

ship adjustment.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the military family members who parti-

cipated in this study. We would also like to thank Drs. Martha

Pelaez, Gary Schulman, Anthony Greene and Henry Soper for

their assistance with this research and Lissette Medina for her

assistance with this manuscript.

REFERENCES

Burrell, L., Adams, G., Durand, D., & Castro, C. (2006). The impact of

military lifestyle demands on well-being, Army, and family out-

comes. Armed Forces and Society, 33, 43-58.

doi:10.1177/0002764206288804

Busby, D., Christensen, C., Crane, D., & Larson, J. (1995). A revision

of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale for use with distressed and non-dis-

tressed couples: Construct hierarchy and multidimensional scales.

Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 21, 289-308.

doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.1995.tb00163.x

Call, V., & Teachman, J. (1991). Military service and stability in the

family life course. Military Psychology, 3, 233-251.

doi:10.1207/s15327876mp0304_4

Card, J. (1983). Lives after Vietnam: The personal impact of military

service. Lexington, MA: D. C. Heath.

Cohen, J. (1992). Statistical power analysis. Current Directions in

Psychological Science, 1, 98-101.

Crane, D., R., Allgood, S., Larson, J. H., & Griffin, W. (1990). Assess-

ing marital quality with distressed and nondistressed couples: A com-

parison and equivalency table for three frequently used measures.

Journal of Marriage and the F amily, 52, 87-93.

doi:10.2307/352841

Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 483