Journal of Water Resource and Protection, 2012, 4, 497-506 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jwarp.2012.47058 Published Online July 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jwarp) Water Service Provision in Owerri City, Nigeria Emmanuella C. Onyenechere1, Sabina C. Osuji2 1Department of Geography & Environmental Management, Imo State University, Owerri, Nigeria 2Department of Urban & Regional Planning, Imo State University, Owerri, Nigeria Email: emmazob@yahoo.com Received March 1, 2012; revised April 2, 2012; accepted May 4, 2012 ABSTRACT The study investigates water service provision in Owerri—a Nigerian city. For the study both primary and secondary data were obtained and analysed. Secondary data were obtained from Imo State Water Corporation (ISWC) and the Works Department of Owerri Municipal Council. While, primary data were obtained from all the 17 wards that consti- tute Owerri city, i.e. the municipal area. Key informants were identified and interviewed using a structured interview schedule. The study found that though most residents of Owerri city rely heavily on commercial borehole owners and water tanker drivers/water peddlers for their daily supplies, the government throu gh its SWA is in control, and there is an absence of a popularly acceptable regulatory framework/water policy. It recommends that Water decree 101 from 1993 (water legislation) be reviewed to address growing challenges. In order to enhance regular water supply at less cost, the study recommends that government should collaborate with the private sector and other community based or- ganizations in a tripartite partnership. A new regulatory framework that will carry out gov ernment ownership and con- trol of water resources and participatory aspects of water management should be produced by ISWC. Keywords: Boreholes; Regulation; State Water Agency; Water Peddlers; Water Policy 1. Introduction Human beings often settle close to water sources b ecause they need water; and human settlements are sustainable only if they have access to potable water. Water re- sources are essential to human development processes and to achieve the Millennium Development Goals that seek, inter alia, to eradicate extreme poverty and hunger, achieve universal literacy, and ensure environmental sus- tainability [1]. There can be no state of positive health and well-being without safe water. For many urban areas the quality of water is becoming a majo r concern. This helps to explain the increasing demand for pota- ble water in urban areas. Water must not only be adequate in quantity, it must also be adequate in quality. The basic physiological re- quirement for drinking water has been established at about 2 litres per person per day. However, a daily sup- ply of 140 - 160 litres per capita is considered adequate to meet all domestic needs [2]. W ater is not only vital fo r all forms of life; also it plays a great role in socio-eco- nomic development: domestic use, agricultural use, in- dustrial use, power generation and recreational use. However, many urban dwellers do not have access to drinking water. UN/WWAP [3] opined that lack of ac- cess to water decreases available time and resources for productive activities and reduces population welfare in developing countries. While MacDonald [4] and WHO [5] affirmed that more than one billion people lack access to safe drinking water, most of whom are sub-Saharan Africans. Generally the provision of drinking water is d i- fficult in African cities because they are characterized by high rates of population growth. Cities are complex sys- tems requiring special methods of prediction and man- agement. The task of the city manager is made more complex by the fact that most of the rapidly growing cities are either located in water stress or water scarce regions, with diminishing per capita water availability or are confronted by issues of control and governance which affect improvement of water supply. In spite of the considerable investment of governments in Nigeria over the years, a large population still does no t have access to water in adequate quantity and quality. It was previously estimated that only 48% of the inhabi- tants of the urban and semi-urban areas of Nigeria and 39% of rural areas had access to potable water supply [6]. In the face of increased demand for water, the average delivery to the urban population stands at only 32 litres per capita per day (lpcd) while that of rural areas stands at 10 lpcd. Unfortunately the widening gap between the demand and supply of water is of crisis proportions in Nigerian cities like Owerri (the capital of Imo State). The plan for water privatization in Nigeria is still be- ing articulated. The Federal Government promotes the policy [7]. Despite all the effort of the federal govern- C opyright © 2012 SciRes. JWARP  E. C. ONYENECHERE, S. C. OSUJI 498 ment, the water supply coverage in the country appears to be decreasing and deteriorating. Current statistics show that for the urban and semi-urban population only about 42% of the population has access to safe water supplies and adequate sanitation. The supplies are being handled by State water agencies (SWAs) that were set up as independent bodies to develop, operate and manage urban wate r s upply undertakings. Most of Nigeria’s SWAs are grappling with multiple problems owing to various reasons; many water works are now supplying less water than they were designed fo r. SWAs have generally failed to provide water services to urban dwellers particularly the urban poor. Since the 1980s water provision through public utilities was fi- nanced through government budgets, relying mainly on donor support and taxe s. Since they were not run on pro- fit, tariffs were minimal for piped connections. This ac- counts for SWA overdependence on subventions from state government. Without increased investment in water and sanitation, city waste and po llution levels will multi- ply. Prior to this period, successive governments in Nigeria and external support agencies have expended millions of naira on the construction of water supply facilities to the extent that some places have up to three facilities exe- cuted by different agencies. In spite of this huge invest- ment, the majority of the people do not have access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation either because most of the installed facilities are not functioning at all or are functioning intermittently. Irregular and inadequate water supply, excessive and inefficient b illing, low water quality and poor consumer service are typical co mplaints. The SWAs do not recover their operating expenses from revenues generated by them; this is because many cus- tomers default in paying bills. With the failure of the state government to provide adequate water supply, people searched for alternative sources of supply. The local government, water vendors and other local entrepreneurs came into the scene and the evidence became the buying and selling of water in the open market across Nigeria. The urban poor became se- rious victims of the trade. In a study of water vending and willingness to pay for water in developing nations (Nigeria inclusive) by Whittington, et al. [8], it was dis- covered that payments made for vended water were more than 20 times the payments made for water from the util- ity. Budds and McGrahanan [9] and Bakker [10] opine that water enterprise is a natural monopoly. Though pro- ponents of the water trade disagree, they believe that water should be treated as a commodity. In their opinion private sector participation in water provision encourages competition which in turn helps in achieving efficiency. However, Budds and McGranahan [9] and Bakker [10] and [11] have all engaged with broader debates over the role of the private sector in water provision, the role of the urban communities in the prov ision of water services and the governance of water. They have drawn the limi- tations facing private companies and governments under privatization arrangements to th e fore, by acknowledging the shortcomings of both privatization and conventional approaches to water provision. The concept of “govern- ance failure” was even introduced by Bakker [11], judg- ing by the fact that the privatization of the water sector is not an absolute remedy to the world’s urban water crisis. The solution to the water crisis is closely linked to how cities are governed and managed. There is need for urban residents to have a larger stake in the planning, development, management and protection of water re- sources for their benefit. This calls for an urgent para- digm shift in urban water governance. Improved gover- nance would also lead to democratization of water usage with acceptable regulations, a view shared by many in- ternational actors and governments e.g. the World Bank. One of the lessons learnt during the water supply and sanitation decade is that government alone at all tiers cannot provide water adequately in a sustainable way. The policies are national and the scene is local, water governance institution s, regulations and rules often apply to people in their own setting and may be limited to a particular ethnic or language group or associated with certain political regimes and may even be used only for certain kinds of water resources. This call to mind the fact that private sector partnerships can be flawed owing to lack of policy direction as observed by K’Akumu and Appida [12]. In the present study con ducted in 2011/2012, th e situa- tion of Owerri city in mind, the research questions are; what is the pattern of water supply provision? Who are the various water service providers? Which of them is in control of municipal water provision in the city? These questions are apt as different players/actors are continu- ously emerging and staying on in the urban water provi- sioning arena. It is hoped that its findings will help in policy formulation. 2. Objectives The objectives of this study are as follows: to examine the pattern of water supply provision in Owerri city; to identify those served and those excluded by the public water distribution system of Owerri city; and to identify those actually in control of Owerri city’s water service provision and management. 3. Methodology The methods of data collection included key informant Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JWARP  E. C. ONYENECHERE, S. C. OSUJI Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JWARP 499 interviews, ordinary interviews, field observations and desk research. Primary data were obtained from all the 17 wards that constitute Owerri city, i.e. the municipal area. A list of the wards within the city was obtained from Imo State Independent Electoral Commission. From the list, key informants were identified and interviewed using a structured interview schedule. Key informant interviews are a way to get “insider information” about an issue, problem, need, or the assets of a community. This is because key informants are knowledgeable about the community/wards, its history and the citizens/resi- dents. They are known to provide detailed information and opinion based on their knowledge of a particular issue. Smaller but focused samples were needed than large samples; this explains why data was not collected from samples of water consumers. It was rather from the ward heads/elders (they served as key informants) that infor- mation on water provision and distribution were col- lected. The key informants were 17 ward heads/elders, seven officials of the State Water Corporation and Ow- erri Municipal Council, ten water tanker drivers, 25 commercial borehole operators, three principal State Government officials, three consultants, and six univer- sity researchers. Secondary data were obtained from Imo State Water Corporation (ISWC) and the Works Depart- ment of Owerri Municipal Council. Some of the primary and secondary data were gathered in non-numeric form, namely; interview transcript, field notes, and audio recordings. Since the numeric data col- lected from the field were not enough to warrant detailed statistical analysis, qualitatively analysis was opted for instead. This research also employed qualitative analysis for the fact that it is limited to only the social analysis of urban water supply, and thus made available results in that context. 4. Results and Discussion The results of the interviews are summarized in Table 1. There are six kinds of water supply provision system found at Owerri city, namely; ISWC, community based provision, self provision, water kiosks, water peddlers, and municipal council supp lies. Owerri city in Imo state with 125,337 inhabitants, is witnessing a rapid rate of urbanization. With a population growth rate of 3.2%, the number of residents keeps swelling. The city has few properly planned layouts and some parts of the city are poorly planned. All these fac- tors have hindered the provision of adequate services to Owerri city dwellers. One of such affected services is water. Currently water provision in Owerri city is poor. It was observed that though majority of the residences are connected to the public water supply in the city, water flow is extremely irregular and people are also forced to resort to alternative sources. The finding is in agreement with the findings of Banerjee et al. [13], who found that piped water reaches most urban Africans more than other Table 1. Current water supply pr ovision at Ower r i city. Wards *ISWC Comm. based: commercial Comm. based: non-commercial Self provisionWater kiosks Water peddlers Municipal council Aladinma I 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 Aladinma II 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 Ikenegbu I 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 Ikenegbu II 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 Ikenegbu III 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 Ikenegbu IV 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 Ekeukwu 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 Azuzi I 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 Azuzi II 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 Azuzi III 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 Azuzi IV 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 Azuzi V 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 Azuzi VI 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 Azuzi VII 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 G.R.A 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 New Owerri I 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 New Owerri II 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 Data Source : Author’s fieldwork (2011). N ote: *Imo State Water Corporation (ISWC); 1: available; 0: not available.  E. C. ONYENECHERE, S. C. OSUJI 500 forms of supply but not as large a share as it had in the early 1990s. The Imo State Water Corporation (ISWC) is the government-approved agency responsible for man- aging the State’s water networks and extending services where necessary in urban centres of the state in an af- fordable and equitable manner. From its inception no ward was excluded, ISWC served all the wards in Owerri city (see Table 1). The ISWC was established in 1995 via Edict No. 35, an era when it had a monopoly because the market was not opened up to competition. Its coverage by April 2011 was only 20% of Owerri city inhabitants down from 70% in 2000. Those inh abitants living at a lower elevation are enjoying the services of the public water corporation more than other inhabitants of the city. Those who live at Aladinma I are the ones worse off. This area has a high elevation which hinders water supply to it. Presently, because of the low capacity of pumps and the fact that the pipelines are not pressurized enough the inhabitants living there cannot be properly served by ISWC. For some others, the reticulation facilities are out-dated and the taps do not run for months or ev en years. The gr eatest bottleneck of ISW C in service provision is infrastructural decay due to lack of funds. With respect to produ ction, most of th e raw water used by ISWC comes from Otamiri River on which the water treatment plant at Otamiri head-works is based. In terms of unaccounted for water mostly through leakages, the level has increased from year to year. It was formerly 35%, but now it is 50%. Acco rding to th e key informants the quality of water at Owerri city is fairly good, ire- spective of whether it is rainy season or dry season. The only threat to its quality is contamination through pipe- lines. Since supply is intermittent when pressure in the pipes drops the contaminants easily seep in through cracks in the pipes. The discharge of River Otamiri is sufficient and there are hardly any complaints of shortages of raw water even during the dry season. At the point of installation, the water facility was meant to generate 66,000 m3/d but it is currently supplying 12,000 m3/d. Many of those served by the ISWC complain to the authorities of inadequacy in quantity. They do not consider the service good enough. The prevalent situation led to a proliferation of various other urban water supply providers in Owerri city, in- crease in water borne diseases and the construction of several substandard commercial and private boreholes in the city. One distinctive feature of ISWC water service is its low tariff, which is lower in comparison with water bought from commercial boreholes or bottled water. The tariff charged is based on flat rate, according to the cate- gory of the buildings or tenements. The lowest tariff is N300 (about US $2) a month for a room connected to the network. For a rooming apartment with water system facilities it is N550 per month; for a three-bedroom flat it is N1500 (See Table 2). Previously as at 2008, it was N50 per room and N350 for a flat of three bedrooms, showing an astronomic increase in tariffs. Occasionally some water tanker drivers looking for brisk business sell to residents of the peri-urban areas water obtained illegally fro m the piped supplies meant to serve neighbourhoods within Owerri city. The manage- ment of ISWC considers such activities illegal. As part of efforts to check such practice, ISWC has warned house- holds not to sell their water to neighbours or abet water tanker drivers that may want to do same, or they would be disconnected. Some households hav e to buy water all the time due to ISWC’s inability to produce enough. Even when a sub- Table 2. Tariffs for water provided by ISWC in 2010. Monthly Tariff Category N US$ Five (5) Room Boys Quarters 1500 10.00 One (1) Room 300 2.00 Rooming Apartment (water system facilities) 550 3.67 One (1) Bedro om Flat 650 4.33 One (1) Bedroom Flat with Boys Quarters 900 6.00 Two (2) Bedroom Flat 1200 8.00 Three (3) Bedroom Flat 1500 10.00 Four (4) Bedroom Flat 2500 16.67 Four (4) Bedroom with Boys quarters 3000 20.00 Single Bungalow with One to Four Rooms 3500 23.33 Single Bungalow with Above Four Rooms 4000 26.67 Data Source: Imo State Water Corporation (2011). Note: US $ s tands for United States o f America’s dollar; Exchange Rate: N150.00 to US $1. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JWARP  E. C. ONYENECHERE, S. C. OSUJI 501 stantial quantity is produced, satisfactory distribution is not always achieved. Sometimes distribution pipes burst from excessive water pressure or old age, and large quantities of treated water are wasted, leading to the ex- clusion of some wards which were hitherto connected to the ISWC’s network. A case in point is Aladinma I which is excluded. Under the community-based water provision there are two kinds, the commercial water providers and the non- commercial water providers. The former see the un- pleasant water supply situation in the city as a business opportunity to provide water supply services in their neighbourhood. They use boreholes as the sources and sell water through PVC piped outlets and PVC overhead tank. It is mostly those in middle and low density areas that patronize commercial borehole owners. The problem for those patronizing commercial borehole operators is the quality and the cost of water. There is no standard tariff for the water sold; its cost varies according to the severity of the water supply problem and source of power supply for pumping machines. The operators do not use water meters nor is a monthly-base tariff applicable. Water is sold as per size of containers used. Commercial boreholes are sometimes the source of water supplied by water peddlers. Generally, the water in a 25-litre jerry can costs N10 irrespective of the season. These community based water providers take up the deficit in official supplies. Thus, in water and sanitation services provision, one new development has been the involvement of the private secto r in service provision. As long as customers are trying to get the most convenient service at the most convenient time and for the amount they are willing to pay, hunting down illegal resellers and regulating a great majority of these providers will not be easy. To curb the water inadequacy wealthy households own private boreholes. Churches and schools, own pri- vate boreholes to o which they use and also of ten provide to neighbourhoods free of charge. They all fall under non-commercial community based water providers, be- cause supply is not fo r profit. The community based water commercial boreholes are actually widespread than any other alternative commer- cial water source. While non-commercial boreholes can be found in all the seventeen wards of Owerri city, community based water commercial boreholes do not exist in all the wards. Ekeukwu, Azuzi I and G.R.A are wards where commercial borehole owners do not operate (see Tabl e 1). Two out of the these three wards are areas with the highest commercial activities in the city (Ekeukwu is the city’s main market, while Azuzi I is on Douglas Road right in front of that market). The G.R.A ward has the seat of government (the Government House) and two five-star hotels. The dominant activities in these wards explain why they are not areas where commercial borehole operation can thrive. In Nigeria decentralization laws in the water resources sector explicitly gave the establishment, operation and maintenance of local water scheme to Local Government Areas/Municipal Councils, in conjunction with the bene- fiting communities. It was based on this mandate that the Owerri city municipal council (local government) had also tried to solve the low coverage of the public Water Corporation by providing water boreholes and elevated water tower without reticulation in 13 out of the 17 wards in the city (see Table 1). Since those were funded and built with the supervision of the Works Unit of the Municipal Council under the framework of participatory approach, after being commissioned they were handed over to the people with the water committees in the bene- fiting wards to manage it on a not-for-profit basis on be- half of the people. Aladinma 1, Aladinma II and Ikeneg- bu III have none due to the fact that they are the highest- income residential wards of the city where the wealthy with several private boreholes live. Azuzi I has none. It is a ward with the Christ church, St Paul’s Catholic Church and the Main Market that have several private not-for- profit boreholes that serve the neighbourhood. The de- tails of the Municipal Council provided boreholes and their location are in Table 3. Funds for these projects were obtained from internally generated revenue and allocation from Federal Govern- ment. Before embarking on any water project that costs more than N500,000, the officials of Owerri Municipal Council (OMC) must first obtain approval from the State Government through the Ministry of Local Government and Chieftaincy Affairs. This indicates that Owerri Mu- nicipal Council suffers from some measure of State Go- vernment control in its efforts to provide necessary ser- vices. The council lacks the heavy equipment and exper- tise for construction of water facilities; as such the pro- jects are contracted out to engineering firms. The Council employs a pro-poor approach to water provision. Its water is tariff free provided the beneficia- ries can levy themselves to ensure that pumps are pow- ered and water is pumped regularly. In the provision of water supply to the people, OMC relies on groundwater abstraction to avoid the huge costs associated with sur- face water abstraction (i.e. treatment and reticulation). Lack of regulatory framework has led to the absence of quality assurance and lack of policy implementation in water provision under this tier of government. Field in- vestigation revealed that no water quality tests were conducted on water from the boreholes upon completion and commissioning. There are no inputs from the Minis- try of Public Utilities and ISWC that ought to monitor them and ensure compliance with acceptable standards. This implies that at that level of governance, water policy issues are not effectively drawn into water provision ac- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JWARP  E. C. ONYENECHERE, S. C. OSUJI 502 Table 3. Water supply facilities provided by the municipal council in Owerri city. Year Description of facility Contractor Contract sum Location of facility Classified information 2,405,00 0 Ikenegbu Girls Sec. School Classified information 2,494,000 Umuihugba hall at Umuodu Classified informatio n 2,496,000 Umuoyima Classified information 2,500,000 Samuel Njemanze Primary School 2005/2006 150 mm diameter boreholes and elevated water towers Classified information Informati o n n ot pr o vi d edArea L, World Bank Housing Estate Health Centre Year Description of facility Location of facility 2009/2010 Modern boreholes with standard twin overhead tanks Tetlow Road by Osuji Street Edede Street by Oguamanam Street Ejiaku Street by Lagos Street No. 184 Tetlow Road Njiribeako Street by Oha Owerre Hall Shell Camp/Alvan CKC Chaplaincy Shell Camp Police Barracks Quarters Hausa/Yoruba Quarters (Amahausa) Nekede Mechanic Village Relief Market New Market Data Sourc e: Owerri Municipal Counc il (2011). tivities. Self-provision households in Owerri City use harvested rainwater as a source of their water supply. According to Thomas [14] it provides safe water for domestic use. Those inhabitants in G.R.A ward that use harvested rain- water have to abandon their dry taps and seek this cost free alternatives. The areas which make up the G.R.A ward are Shell Camp, Alvan CKC Chaplaincy, th e Police Barracks, the Government House and Government Col- lege. These residents are low-income and middle-income earners and chose to resort to rainwater harvesting be- cause of its cost effectiveness. However, storage tanks and drums for collected rainwater should have covers to avoid the invasion of algae or other biotic compounds that may alter its quality [15]. From Table 1, only one ward uses self provision. It is not a popular source of water supply and this is simply because rainwater har- vesting has never been an urban option and it is still not one. Water in bottles and in nylon sachets known as “pure water” is popular in some wards. These wards are Ikenegbu II, Azuzi I, Azuzi III and New Owerri I. One thing common to these four wards is that they are high- density areas, where unmet high demand for water will have to be supplemented by other readily available water sources such as packaged water. The water sold at the water kiosks is said to from springs that exist in some Local Government Areas of the State. Th e 19 litres bo ttle is sold for N2000 (US $13.33). Usually the gallon/con- tainer is owned by some customers. Those customers who buy only water using their container pay as little as N300 (about US $2) for the refill. A bottle of 1.5 litre capacity is sold for N100 (US $0.67), while a crate of 12 such bottles is sold for N1200 (US $8). These bottles have brand names printed on them. Some of the produ- cers claim that before the raw is packaged, it is processed by an ozone machine to make it drinkable. The water from water kiosks is mainly for drinking. The sachet wa- ter costs less than the bottled water. A sachet of 0.5 litres cost N10 (US $0.07), while a big nylon bag of 20 sachets (10 litres) cost N100 (US $0.67). Shofuyi [16] warns that the indiscriminate disposal of these non-biodegradable containers have compounded problems of environmental sanitation. In Azuzi I, Azuzi II, G.R.A and New Owerri II wards, households depend on water peddlers for their supplies. Residents of these wards live in compounds that have sufficient space for large PVC tanks for water bought from peddlers. In Azuzi I the residents that patronize water peddlers have their tanks right in front of their premises. Those at Azuzi VI and New Owerri II that buy from water peddlers keep their own tanks in their prem- ises at the back of their buildings. The peddlers sell water in bulk and the buyer must at any point in time buy a tanker load. The water peddlers have four agglomeration points located in wards with the most acute water problems. On the average, 25 tankers are registered at each agglomera- tion point, and the tanker drivers belong to a union. The business is becoming so lucrative that some commercial borehole owners own water tankers that fill up at their boreholes and move around in search of patronage. Wa- ter peddlers do not suffer from government interference, a situation which keeps them outside any regulatory framework other than their own. The water peddlers obtain water for sale mostly from Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JWARP  E. C. ONYENECHERE, S. C. OSUJI 503 commercial boreholes and occasionally from Otamiri River. To fill a 5000-litre tanker, the driver pays N500 (US $3.34). It costs N1000 (US $6.67) to fill a 10,000- litre tanker. If the abstraction into a water tanker is di- rectly from a river, it costs N300 (US $2) to fill up ire- spective of the tanker’s capacity. W ater is sold in tankers and not drums or buckets as is often the case in some peri-urban and rural areas. Water from a 5000-litre tanker costs N2000. Prices may vary; but often distance is the major determinant of price difference. By Edict 35 of 1995, the Imo State government estab- lished the State Water Corporation (ISWC) empowering it to construct, operate and maintain waterworks station s, building and other works; abstract water from any lake, river, stream or natural water sources within Imo State; enter upon any land any time for the purpose of examin- ing repairing or removing any water-pipe belonging to the corporation; construct public fountains in any street or other public places; enter into or upon any tenement between the hours of six o’clock in the morning and six o’clock in the evening or in an emergency in order to inspect any services or to disconnect the supply of water; enter to contracts subject to the prevailing tenders and awards of contract procedure as may be necessary; di- minish, withhold, suspend, stop, turn-off or divert the supply of water; enter into agreement with any person for the supply, construction, manufacture, maintenance or repair of any property for the performance of its func- tions; write off bad debts with the approval of the Gover- nor in writing; and determine adequate charges or fees which shall be approved by government for water supply and treatment. The National Water Supply and Sanitation Policy (NWSSP) document of FMWR [6], and the National Water Policy document of FRN [17], recognized and gave ISWC and other sister agencies mandate and re- sponsibilities for the establishment, operation, quality control and maintenance of urban and semi-urban water supply systems. It empowered them to encourage private ownership of water supply and san itation facilities and to license and monitor private water supply and quality of water supply to the public. The entire decrees and edict in the legal framework and the mandate provided by the water policy documents are tools of empowerment, do- minance and control of water supply and sanitation pro- vision in the city. Those are pointers to the fact that the state government through its agency, the state water cor- poration, despite its peculiar constraints, is in control. Its scale of provision both in terms of quantity and quality cannot be equaled by any other category of water and sanitation service provider in Owerri city. Table 4 is a catalogue of water consumer units in Owerri city served by ISWC in 2008. Its distribution network spans across the entire seventeen wards of Owerri city, and can pro- Table 4. Water consumer units served by ISWC in Owerri city in 2008. Category Number of units Residential homes 33,111 Hotels 113 Hospitals/clinics 78 Banks 21 Car-wash enterprises 138 Block industries 137 Fuel stations 36 Hair dressing salons 13 Institutions 401 Data sourc e: Imo state water corporation (2011). vide services to all when provid ing at full capacity. ISWC has the advantage of possessing reticulation and distribution network as well as treatment plant which other providers do not have and it does not depend on groundwater. The ISWC also has state government pre- sence. However the political will to ensure efficiency and maximum output in the running of its day to day activi- ties or to provide water adequately in the city is lacking. Strategies for boosting its services are lacking and that is why till date ISWC has not been able to provide water meters to consumers in line with the NWSSP document’ recommendation. It has not succeeded in funding its ac- tivities sufficiently from monies realized from charges nor has it sourced for external loans to overhaul its sys- tem. Currently, the ISWC’s control of Owerri city’s water and sanitation service provision is not in doubt, but its short-comings which undermine its powers have to be highlighted. From field observation, it was discovered that ISWC does not collaborate with Owerri Municipal Council (OMC) in water and sanitation services provi- sion. It is due to ISWC’s non-provision of technical as- sistance to the Municipal Council water supply unit that resulted in OMC’s engagement of engineering construc- tion firms for construction of its facilities. ISWC does not have a popularly acceptable regulatory framework and does not monitor other providers nor does it provide them licenses with which to operate. ISWC ought to re- gulate the activities of o ther providers and ensure th at the quality of water provided is high and their charges will not exclude the poor from being served. Since the Na- tional Water Policy (NWP) mandates SWAs to encour- age private ownership of water supply and sanitation facilities, regulating them is imperative. ISWC has not yet adopted the National Water Policy of 2004, nor has it adapted the policy to su it local needs and peculiarities as it is expected. Though the edict establishing ISWC sti- pulated that it performs certain specific functions, for Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JWARP  E. C. ONYENECHERE, S. C. OSUJI 504 some reasons the act has not been effectively enforced. The failure of ISWC to deliver services to 125,337 Owerri city dwellers puts groundwater in jeopardy and endangers groundwater sustainability in the long run. The other alternative sources all abstract groundwater except where rain water is harvested. On the average 20 boreholes (estimated number) exist in every ward in Owerri city. Groundwater is also a preferred source be- cause it is a common prop erty resource. The onus lies on ISWC to fore warn the public of over dependence on groundwater, especially of the long term implications. It has been known to deplete and degrade groundwater and affect continuous aquifer systems in communities where water is used for both domestic an d agricultural purposes [18]. Burke & Moench [19] are of the view that legisla- tion and regulation would help nip this likely problem in the bud. During the o il boom days of the 1970 s and earl y 1980s, the country invested heavily in water resources develop- ment. It was in this era that the Imo State Government designed and constructed its Otamiri Regional Water Scheme. A scheme it has depended on till date. The in- stitutional arrangement for water resources development and management is such that all tiers of government, which is Federal, States and Local Government, are in- volved. These tiers of government at one time or the other have had collaborations with external support agen- cies which they appreciated and felt was encouraging. However, one of the challenges facing the sector is frag- mented and uncoordinated water resources development, while another is rapidly rising water supply costs. To meet its funding needs, the Federal Government stipulates that there is need for active private sector par- ticipation. Previously state government assumed respon- sibility for overall management of the state’s water re- sources, and did not involve stakeholders in water re- sources development. That trend led to its water supply projects providing services that do not meet consumer needs and for which the consumers are unwilling to pay for. From inception of the regional water scheme till date water has been highly subsidized in Owerri city, and this has been financially burdensome for the state govern- ment. In Imo State there is need for a re-orientation to the fact that people have to be kept at the centre of the con- cern for water management and development. It should be conducted on a participatory basis with decision mak- ing occurring at the lowest appropriate level. There is also a growing recognition in line with international views and requirements, that greater emphasis must be placed on the management of demand for water as an economic good, to make sure that water use is efficient and it does not compromise environmental requirements. The previous approach to water resources development that has resulted in inefficiency in service provision in- volved treating water as a public social good. The Federal Government recognizes the fact that the role of a regulatory frame work cannot be undermined in any circumstance, because according to it, water is too valuable a commodity for its management to be handed over solely to its users. Thus government must be in the picture to play a vital role in monitoring and enforcement of compliance with water policies and laws. Presently the Federal Government is of the opinion that water services can be delivered through public, pri- vate or community based institutions. Water pricing is important. Cost recovery of these services is also neces- sary to ensure their long-term utilization. Government should change its role from being an implementer to be- ing a regulator, facilitator and coordinator in order to help improve efficiency and effectiveness in private sec- tor delivery of water services. It is a new strategy in conformity with the on-going reforms in the pub lic sector. There is need for an independent regulatory body (made up of professional bodies, local officials, government officials, community members, technocrats, NGOs, and other resource users) to be created to mediate between government and their private contract partners from the public private partnerships in water and sanitation service provision. All the problems concern management, roles and re- sponsibilities, accountability, maintenance of scheme, in- adequate coordination or customer involvement. Accord- ing to the United Nations Secretary-General, wider ac- cess to clean water can be achieved through the streng- thening of institutional capacity and governance at all levels, promoting more technology transfer, mobilizing more financial resources and scaling up good practices and lessons learned. To this end, commitment to carry out profound new reforms in the way the water supply and sanitation sector is managed at the national, state and local level is beginning to ex ist. According to some scholars, reforms in Nigeria’s wa- ter and sanitation sector have been partly based on ex- pectation of loans from multilateral financial institutions and foreign investments, more so as World Bank has explicitly made financing conditional on water reform. The assistance of international actors and development partners has always been sought in the water sector in Nigeria, its 36 states and numerous L.G.As. It is evident that it is because the challenges are myriad and it can not tackle it in isolation of the International Community that it has always tried to draft its policies to attain and main- tain internationally acceptable standards. The interna- tional actors involved in water supply in Nigeria are World Bank, the African Development Bank, USAID, WaterAid, EU, JICA, UNICEF, UNDP, CIDA and ZONTA International. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JWARP  E. C. ONYENECHERE, S. C. OSUJI 505 The World Bank has been providing assistance to Ni- geria in water supply since 1979. It even entered an agreement with the Federal Ministry of Agriculture, Wa- ter Resources and Rural Development, and the sum of US $250 million was released in 1992 to fin ance the Na- tional Water Rehabilitation Project (NWRP). The Old Imo State like other nineteen states of the Federal and the Federal Capital Territory Abuja received $10 million. Between 1991 and 2001, Otamiri scheme serving Owerri city got expanded and this ushered in improved services but this dwindled again with time. The real challenge in external support is coordination which has produced a fragmented actor scene. The drawing of erroneous con- clusions about the scale of the problem due to lack of statistics is also a contributing factor. The multilateral development agen cies are supposed to support and reinforce local effort and capacity and this is lacking. Their projects for water should actually com- plement local development structures, institutions and agencies and not duplicate or undermine them. However, the World Bank got its intervention of 1992 as well as other interventions assessed. The Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) of the World Bank considers its interven- tion in Nigeria up to 2005 to have failed; many were rated as unsatisfactory with unlikely sustainability and with negligible or modest institutional development im- pact [20]. With respect to the promotion of reforms in the water sector, the World Bank has repositioned itself more stra- tegically. The Bank has no longer limited itself to pro- moting loans but also to promoting policy reform [21]. The goals of the Bank for the water sector in 2005-2009 country partnership paper were prepared for Nigeria by the Bank and DFID. This is a clear indication that multi- lateral and bilateral agencies have a shared vision on wa- ter and sanitation services provision in Nigeria. They are all advocates of the involvement of private sector, NGO and government in delivery of water services. With the unanimous agreement among them, Nigerian government has moved in the desired direction by producing a Na- tional Water Supply and Sanitation Policy Document in 2000 and a National Water Policy Document in 2004 to guide the water sector. These are instruments for the ref- ormation of the sector and the ushering in of Public Pri- vate Partnerships (PPP). With decentralization the federal government has set the stage for state governments and local governments to follow. Among the generality of Nigeria people, it has remained an unpopular refo rm; this is because they do not want powerful international agents to push government into hasty partnerships that they will regret in the longer term. Therefore the notion that water is an economic good must be handled with care in Nige- ria, where access to adequate water and sanitation is still at its lowest ebb. In Imo State where Owerri city is capital, the govern- ment has the Rescue Mission Agenda. It is a develop- ment strategy document of State Government detailing the government’s policy thrust. It has started making efforts to introduce Public Private Partnership (PPP) in water supply. To improve service delivery and make the State Water Agency less dependent on state government treasury, towards the end of 2011 a memorandum of un- derstanding was signed with a South African firm known as the West African Utilities Metering System and Ser- vices Limited to take over the management of the water schemes in the state, according to Iwuala [22]. Since Owerri city’s water and sanitation service provision is yet to be fully privatized, the state government still re- tains its monopoly and public interest is still considered paramount in water governance. The public, who consti- tute the electorate, would most likely vote for a guberna- torial candidate considers their interest above that of state. The state lacks a comprehensive water policy document, this seems to agree with Adeoti [23 ], view that numerous policy guidelines for water and sanitation exist only at the federal level in Nigeria. Nigeria is in a democracy, and PPP is a politically sensitive issue. This explains why there is a slow speed in its adoption at the state or local government level right now. For effectiveness of policies and programmes in the water sector, they shou ld be adjusted to or tailored towards local social and cul- tural realities. It should be carefully explained to all wa- ter users especially the poor. It is a fact that citizens of Owerri city use different water sources, but the distance from the supply source, the associated hard ship, susceptibility to diseases and the cost of water are very critical. When the suffering is weighed against the gains, the majority of the residents of Owerri city may accept PPP, especially if they are co-opted into its realization. Regarding water as an eco- nomic good and privatizing it without adequate explana- tion might make the profit motive paramount which could affect both the afford ability and the accessibility of water. Since the poverty profile in Nigeria reveals that more than 70 percent live below the poverty line of US $1 per day [24], an element of cross-subsidization may be required to produce a sustainable way out. 5. Conclusions and Recommendations Water and sanitation provision analysis is useful for po- licy intervention and programme formulation. Action on the ground often requires information on forms of provi- sion already existing. The study rev eals that water supply from ISWC is the best form of water provision. However, the role of the private sector in water provision is very important as such should not be disregarded. Service provision problems can be addressed through govern- ment’s collaboration with the private sector and the com- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JWARP  E. C. ONYENECHERE, S. C. OSUJI Copyright © 2012 SciRes. JWARP 506 munity based organizations. The water users should not be left out. The tripartite arrangement should enhance water provision, if well regulated and managed. It also recommends that Water decree 101 from 1993 (water legislation) be reviewed to address growing chal- lenges. A new regulatory framework that will carry out government ownership and control of water resources and participatory aspects of water management should be produced by ISWC. Currently, to regulate other urban water and sanitation service providers, ISWC should introduce stringent controls in areas of water quantity and quality, provide procedures for water quality man- agement, regulate groundwater abstraction and protect surface water from over exploitation and pollution and establish a list of fees for abstraction o f groundwater and surface water and also for sales of abstracted water. It should resolve disputes on water, and with the help of government, it should institutionalize into statutes rele- vant customary laws and practices that relate to water supply and management. REFERENCES [1] M. A. Hanjra, T. Ferede and D. G. Gutta, “Reducing Pov- erty in Sub-Saharan Africa through Investments in Water and Other Priorities,” Agricultural Water Management, Vol. 96, No. 7, 2009, pp. 1062-1170. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2009.03.001 [2] P. Gleick, “Basic Requirements for Human Activities: Meeting Basic Needs,” International Water, Vol. 21, No. 2, 1996, pp. 83-92. [3] United Nations/World Water Assessment Programme (UN/WWAP), “Water for People, Water for Life,” 2003, Accessed 27 October 2011. http://unesdocunesco.org/images/0012/001295/129556e.p df [4] A. M. MacDonald, “Developing Groundwater: A Guide for Rural Water Supply,” ITDG Publishing, New York, 2005. [5] World Health Organization (WHO), “Water Recreation and Diseases,” IWA Publishing, London, 2005. [6] Federal Ministry of Water Resources (FMWR), “ National Water Supply and Sanitation Policy Document,” Abuja, 2000. [7] A. Ariyo and A. Jerome, “Utility Privatization and the Poor: Nigeria in Focus,” Global Issue Papers for Heinrich Boll Stiftung, No. 12, June 2004. [8] D. Whittington, D. T. Lauria, D. A. Okun and X. Mu, “Water Vending Activities in Developing Countries,” In- ternational Journal of Water Resource Development, Vol. 5, No. 3, 1989, pp. 158-168. [9] J. Budds and G. McGranahan, “Privatization Missing the Point? Experiences from Africa, Asia and Latin Amer- ica,” Environment and Urbanization, Vol. 15, No. 2, 2003, pp. 87-113. [10] K. Bakker, “Archipelagos and Networks: Urbanisation and Water Privatization in the South,” The Geography Journal, Vol. 169, No. 4, 2003, pp. 328-341. doi:10.1111/j.0016-7398.2003.00097.x [11] K. J. Bakker, “Privatizing Water: Governance Failure and the World’s Urban Water Crisis,” Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 2010. [12] A. O. K’Akumu and P. O. Appida, “Privatization of Ur- ban Water Service Provision: The Kenyan Experiment,” Water Policy, Vol. 8, No. 4, 2006, pp. 313-324. doi:10.2166/wp.2006.044 [13] S. Banerjee, H. Skilling, V. Forster, C. Briceno-Garmen- dia, E. Morella and T. Chfadi, “Africa Infrastructure Country Diagnostic: Urban Water Supply in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Report by the World Bank and the Water and Sanitation Programme, Washington DC, 2008. [14] T. Thomas, “Domestic Water Supply Using Rainwater Harvesting,” Building Research and Information, Vol. 2, No. 2, 1998, pp. 94-101. doi:10.1080/096132198370010 [15] J. D. Njoku and A. Ubuoh, “Quality of Rainwater in Stor- age Tanks in Selected Locations in Mbaitoli LGA of Imo State,” In: U. M. Igbozurike, M. A. Ijioma and E. C. On- yenechere, Eds., Rural Water Supply in Nigeria, Cape Publishers, Owerri, 2010, pp. 175-183. [16] S. Shofuyi, “Study X-Rays Poor Quality of ‘Pure Water’ in Nigeria,” The Punch, No. 4, 2003. [17] Federal Republic of Nigeria (FRN), National Water Pol- icy Document, Abuja, Nigeria, 2004. [18] W. Hadipuro and N. Y. Indriyanti, “Ty pical Urban Wate r Supply Provision in Developing Countries: A Case Study of Semarang City, Indonesia,” Water P olicy, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2009, pp. 55-66. doi:10.2166/wp.2009.008 [19] J. J. Burke and M. H. Moench, “Groundwater and Society: Resources, Tensions and Opportunities,” United Nations Publication, New York, 2000. [20] World Bank, “Project Assessment Report: Nigeria,” No. 36443, World Bank, Washington DC, 2005. [21] M. Goldman, “Imperial Nature: The World Bank and Struggles for Social Justice in the Age of Globalization,” Yale University Press, London, 2005. [22] E. N. Iwuala, “Imo Water Corporation and the Rescue Mission Agenda,” Imo Trumpeta, No. 5, 7 February 2012. [23] O. Adeoti, “Challenges to Managing Water Resources along the Hydrological Boundaries in Nigeria,” Water Policy, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2007, pp. 105-118. doi:10.2166/wp.2006.002 [24] Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), “Nigeria’s Development Prospects: Poverty Assessment and Alleviation Study,” CBN, Lagos, 1999.

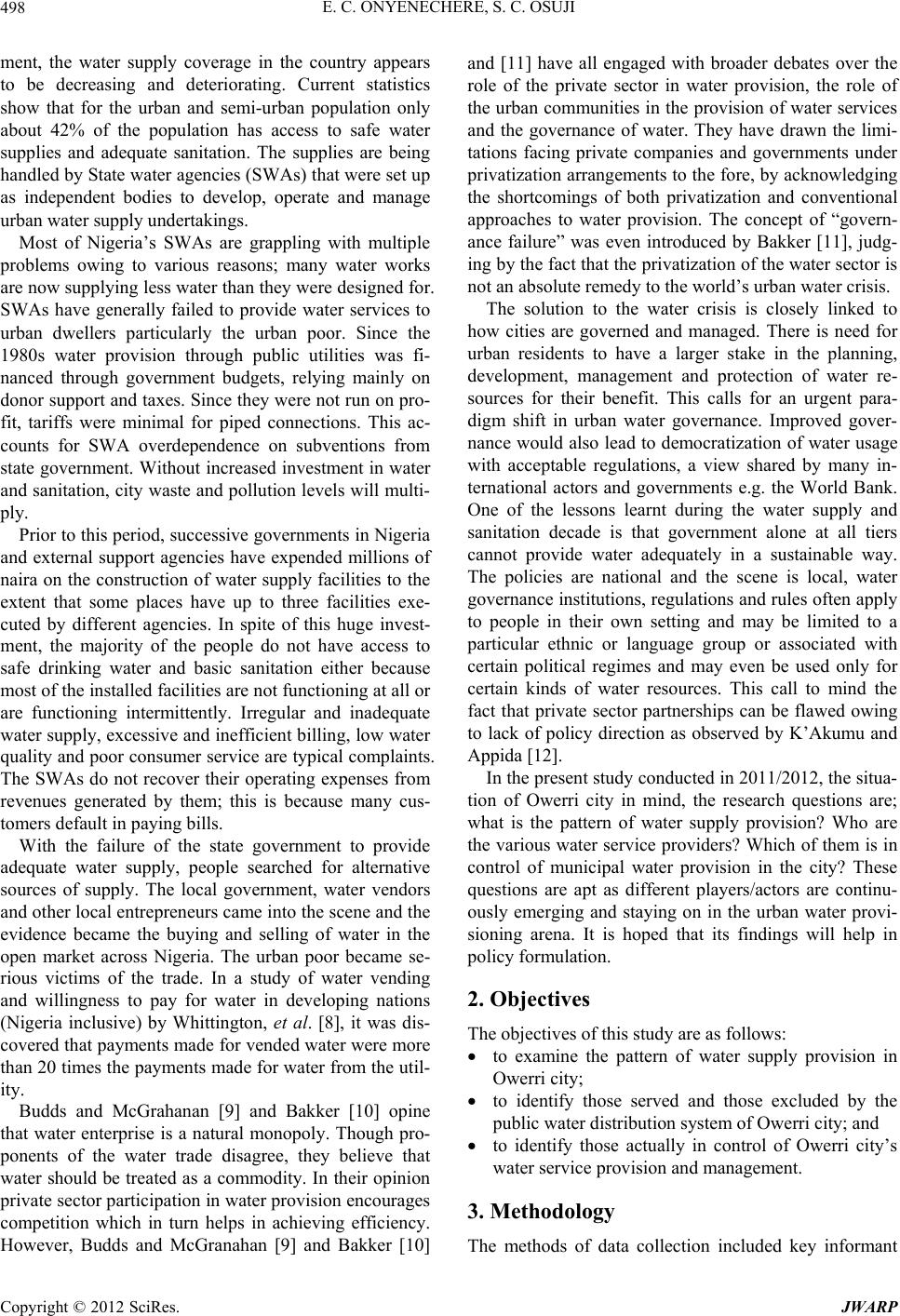

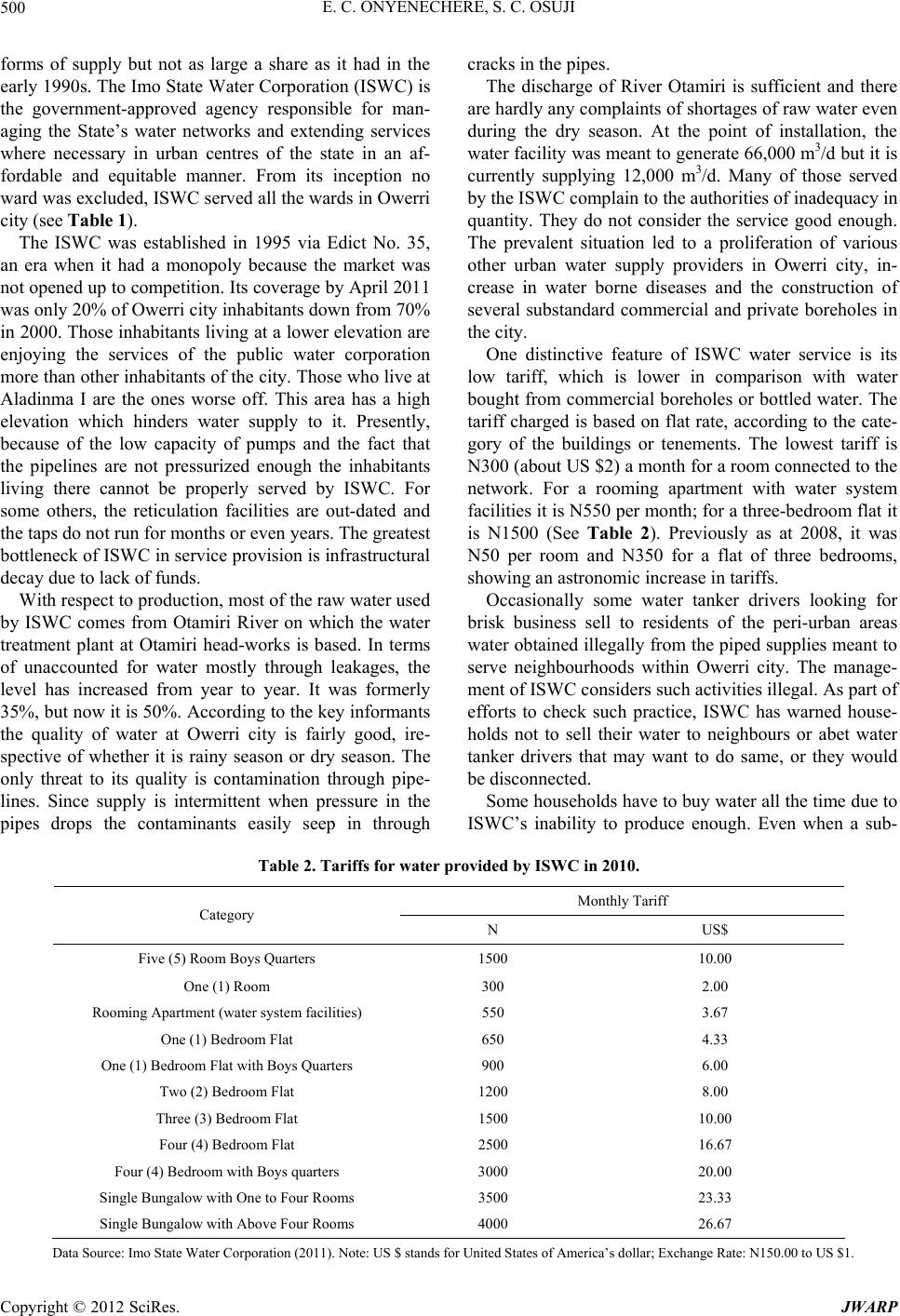

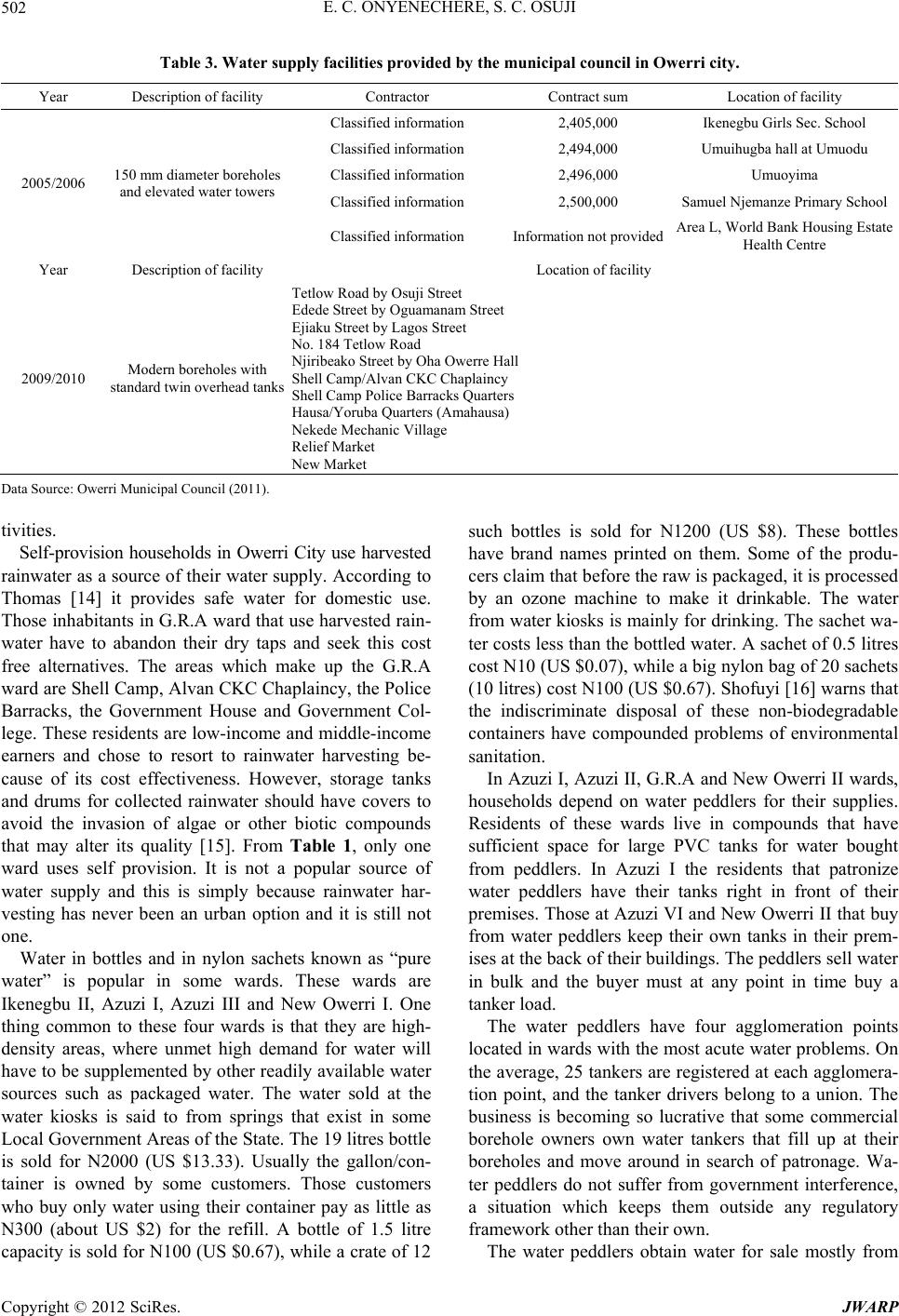

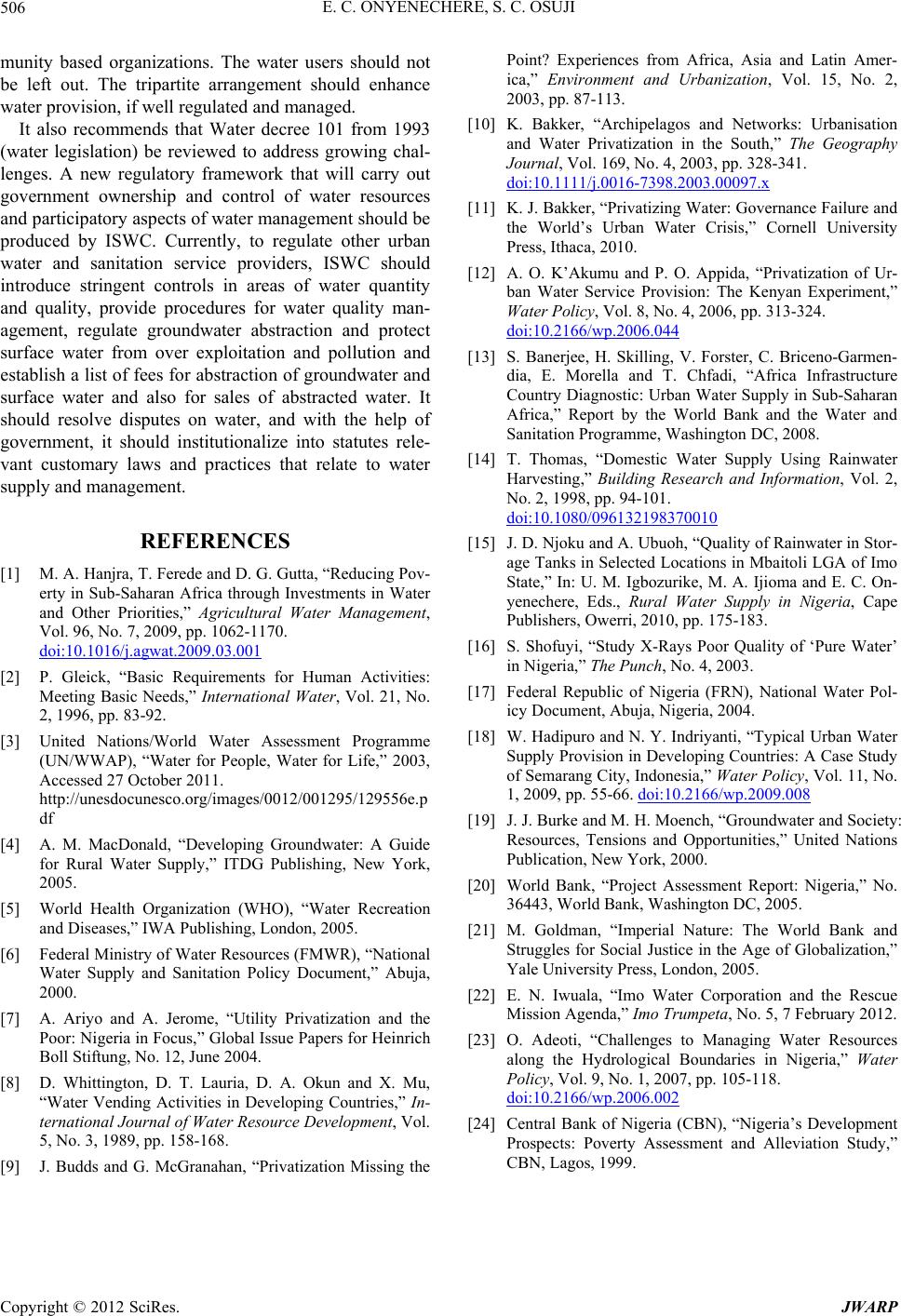

|