H. C. WANG ET AL.

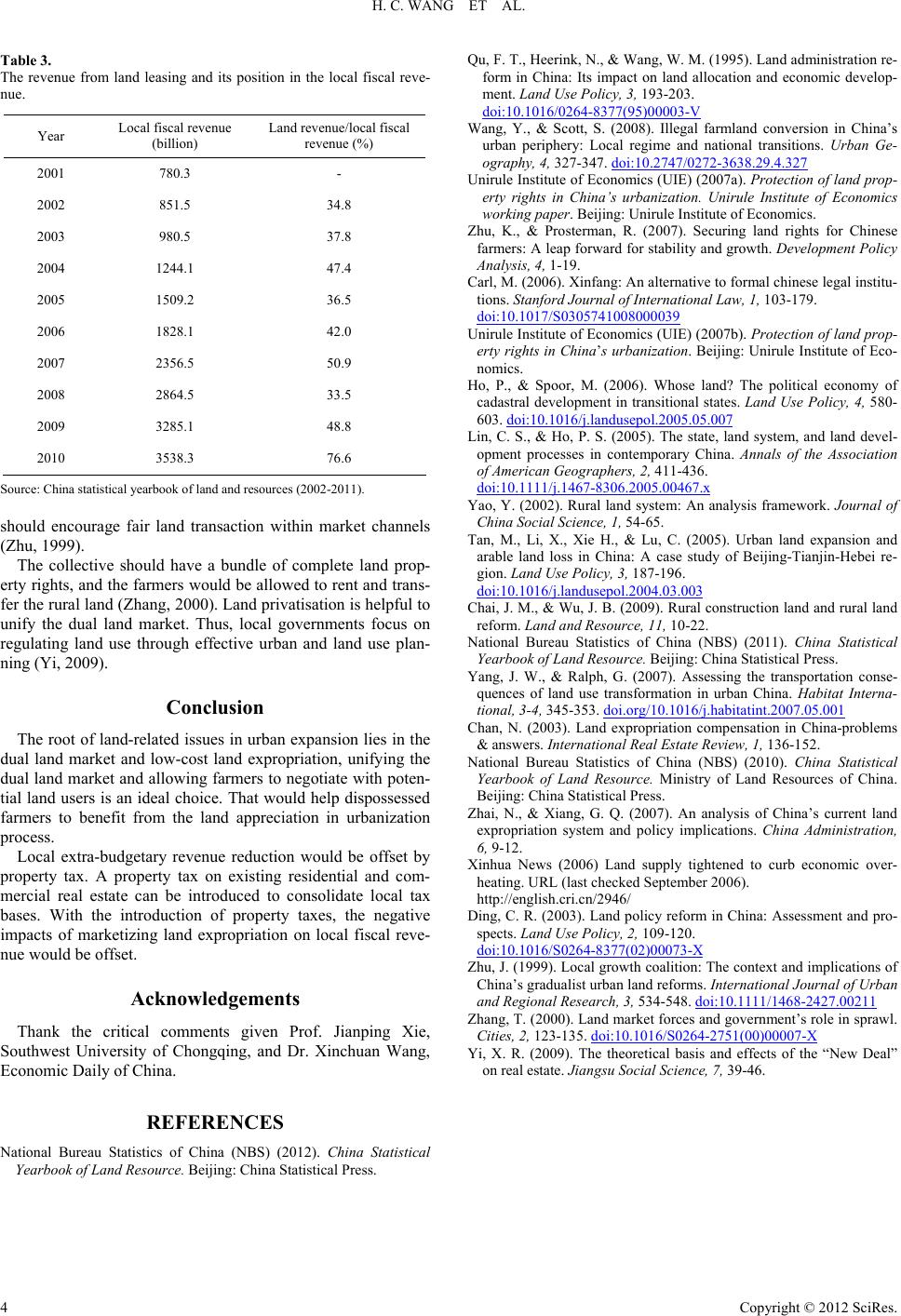

Table 3.

The revenue from land leasing and its position in the local fiscal reve-

nue.

Year Local fiscal revenue

(billion) Land revenu e/local fisc al

revenue (%)

2001 780.3 -

2002 851.5 34.8

2003 980.5 37.8

2004 1244.1 47.4

2005 1509.2 36.5

2006 1828.1 42.0

2007 2356.5 50.9

2008 2864.5 33.5

2009 3285.1 48.8

2010 3538.3 76.6

Source: China statistical yearbook of land and resources (2002-2011).

should encourage fair land transaction within market channels

(Zhu, 1999).

The collective should have a bundle of complete land prop-

erty rights, and the farmers would be allowed to rent and trans-

fer the rural land (Zhang, 2000). Land privatisation is helpful to

unify the dual land market. Thus, local governments focus on

regulating land use through effective urban and land use plan-

ning (Yi, 2009).

Conclusion

The root of land-related issues in urban expansion lies in the

dual land market and low-cost land expropriation, unifying the

dual land market and allowing farmers to negotiate with poten-

tial land users is an ideal choice. That would help dispossessed

farmers to benefit from the land appreciation in urbanization

process.

Local extra-budgetary revenue reduction would be offset by

property tax. A property tax on existing residential and com-

mercial real estate can be introduced to consolidate local tax

bases. With the introduction of property taxes, the negative

impacts of marketizing land expropriation on local fiscal reve-

nue would be offset.

Acknowledgements

Thank the critical comments given Prof. Jianping Xie,

Southwest University of Chongqing, and Dr. Xinchuan Wang,

Economic Daily of China.

REFERENCES

National Bureau Statistics of China (NBS) (2012). China Statistical

Yearbook of Land Reso urc e. Beijing: China Statistical Press.

Qu, F. T., Heerink, N., & Wang, W. M. (1995). Land administration re-

form in China: Its impact on land allocation and economic develop-

ment. Land Use Policy, 3, 193-203.

doi:10.1016/0264-8377(95)00003-V

Wang, Y., & Scott, S. (2008). Illegal farmland conversion in China’s

urban periphery: Local regime and national transitions. Urban Ge-

ography, 4, 327-347. doi:10.2747/0272-3638.29.4.327

Unirule Institute of Economics (UIE) (2007a). Protection of land prop-

erty rights in China’s urbanization. Unirule Institute of Economics

working paper. Beijing: Unirule Institute of Eco nomics.

Zhu, K., & Prosterman, R. (2007). Securing land rights for Chinese

farmers: A leap forward for stability and growth. Development Policy

Analysis, 4, 1-19.

Carl, M. (2006). Xinfang: An alternative to formal chinese legal institu-

tions. Stanford Journal of International Law, 1, 103-179.

doi:10.1017/S0305741008000039

Unirule Institute of Economics (UIE) (2007b). Protection of land prop-

erty rights in China’s urbanization. Beijing: Unirule Institute of Eco-

nomics.

Ho, P., & Spoor, M. (2006). Whose land? The political economy of

cadastral development in transitional states. Land Use Policy, 4, 580-

603. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2005.05.007

Lin, C. S., & Ho, P. S. (2005). The state, land system, and land devel-

opment processes in contemporary China. Annals of the Association

of American Geographers, 2, 411-436.

doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.2005.00467.x

Yao, Y. (2002). Rural land system: An analysis framework. Journal of

China Social Science, 1 , 54-65.

Tan, M., Li, X., Xie H., & Lu, C. (2005). Urban land expansion and

arable land loss in China: A case study of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei re-

gion. Land Use P olicy, 3, 187-196.

doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2004.03.003

Chai, J. M., & Wu, J. B. (2009). Rural construction land and rural land

reform. Land and Resource, 11, 10-22.

National Bureau Statistics of China (NBS) (2011). China Statistical

Yearbook of Land Reso urc e. Beijing: China Statistical Press.

Yang, J. W., & Ralph, G. (2007). Assessing the transportation conse-

quences of land use transformation in urban China. Habitat Interna-

tional, 3-4, 345-353. doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2007.05.001

Chan, N. (2003). Land expropriation compensation in China-problems

& answers. International Real Estate Review, 1, 136-152.

National Bureau Statistics of China (NBS) (2010). China Statistical

Yearbook of Land Resource. Ministry of Land Resources of China.

Beijing: China Statistical Press.

Zhai, N., & Xiang, G. Q. (2007). An analysis of China’s current land

expropriation system and policy implications. China Administration,

6, 9-12.

Xinhua News (2006) Land supply tightened to curb economic over-

heating. URL (last checked Septembe r 2006).

http://english.cri.cn/2946/

Ding, C. R. (2003). Land policy reform in China: Assessment and pro-

spects. Land Use Policy, 2, 109-120.

doi:10.1016/S0264-8377(02)00073-X

Zhu, J. (1999). Local growth coalition: The context and implications of

China’s gradualist urban land reforms. International Journal of Urban

and Regional Research, 3, 534-548. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.00211

Zhang, T. (2000). Land market forces and government’s role in sprawl.

Cities, 2, 123-135. doi:10.1016/S0264-2751(00)00007-X

Yi, X. R. (2009). The theoretical basis and effects of the “New Deal”

on real estate. Jiangsu Social Science, 7 , 39-46.

Copyright © 2012 SciRes.

4