Iris Repair after Long-Term Complications of Angle-Supported Phakic Intraocular Lenses

42

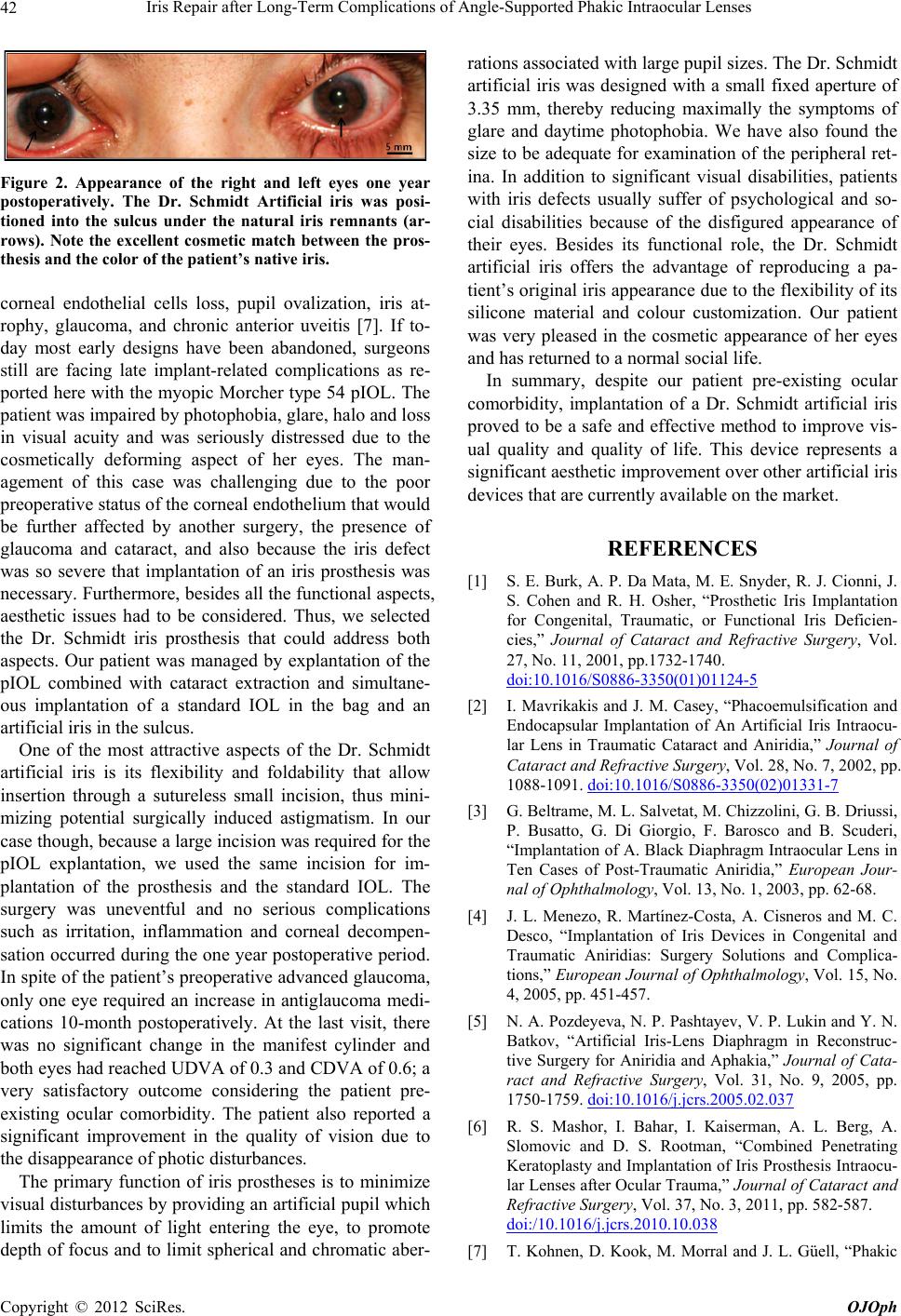

Figure 2. Appearance of the right and left eyes one year

postoperatively. The Dr. Schmidt Artificial iris was posi-

tioned into the sulcus under the natural iris remnants (ar-

rows). Note the excellent cosmetic match between the pros-

thesis and the color of the patient’s native iris.

corneal endothelial cells loss, pupil ovalization, iris at-

rophy, glaucoma, and chronic anterior uveitis [7]. If to-

day most early designs have been abandoned, surgeons

still are facing late implant-related complications as re-

ported here with the myopic Morcher type 54 pIOL. The

patient was impaired by photophobia, glare, halo and loss

in visual acuity and was seriously distressed due to the

cosmetically deforming aspect of her eyes. The man-

agement of this case was challenging due to the poor

preoperative status of the corneal endothelium that would

be further affected by another surgery, the presence of

glaucoma and cataract, and also because the iris defect

was so severe that implantation of an iris prosthesis was

necessary. Furthermore, besides all the functional aspects,

aesthetic issues had to be considered. Thus, we selected

the Dr. Schmidt iris prosthesis that could address both

aspects. Our patient was managed by explantation of the

pIOL combined with cataract extraction and simultane-

ous implantation of a standard IOL in the bag and an

artificial iris in the sulcus.

One of the most attractive aspects of the Dr. Schmidt

artificial iris is its flexibility and foldability that allow

insertion through a sutureless small incision, thus mini-

mizing potential surgically induced astigmatism. In our

case though, because a large incision was required for the

pIOL explantation, we used the same incision for im-

plantation of the prosthesis and the standard IOL. The

surgery was uneventful and no serious complications

such as irritation, inflammation and corneal decompen-

sation occurred during the one year postoperative period.

In spite of the patient’s preoperative advanced glaucoma,

only one eye required an increase in antiglaucoma medi-

cations 10-month postoperatively. At the last visit, there

was no significant change in the manifest cylinder and

both eyes had reached UDVA of 0.3 and CDVA of 0.6; a

very satisfactory outcome considering the patient pre-

existing ocular comorbidity. The patient also reported a

significant improvement in the quality of vision due to

the disappearance of photic disturbances.

The primary function of iris prostheses is to minimize

visual disturbances by providing an artificial pupil which

limits the amount of light entering the eye, to promote

depth of focus and to limit spherical and chromatic aber-

rations associated with large pupil sizes. The Dr. Schmidt

artificial iris was designed with a small fixed aperture of

3.35 mm, thereby reducing maximally the symptoms of

glare and daytime photophobia. We have also found the

size to be adequate for examination of the peripheral ret-

ina. In addition to significant visual disabilities, patients

with iris defects usually suffer of psychological and so-

cial disabilities because of the disfigured appearance of

their eyes. Besides its functional role, the Dr. Schmidt

artificial iris offers the advantage of reproducing a pa-

tient’s original iris appearance due to the flexibility of its

silicone material and colour customization. Our patient

was very pleased in the cosmetic appearance of her eyes

and has returned to a normal social life.

In summary, despite our patient pre-existing ocular

comorbidity, implantation of a Dr. Schmidt artificial iris

proved to be a safe and effective method to improve vis-

ual quality and quality of life. This device represents a

significant aesthetic improvement over other artificial iris

devices that are currently available on the market.

REFERENCES

[1] S. E. Burk, A. P. Da Mata, M. E. Snyder, R. J. Cionni, J.

S. Cohen and R. H. Osher, “Prosthetic Iris Implantation

for Congenital, Traumatic, or Functional Iris Deficien-

cies,” Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery, Vol.

27, No. 11, 2001, pp.1732-1740.

doi:10.1016/S0886-3350(01)01124-5

[2] I. Mavrikakis and J. M. Casey, “Phacoemulsification and

Endocapsular Implantation of An Artificial Iris Intraocu-

lar Lens in Traumatic Cataract and Aniridia,” Journal of

Cataract and Refractive Surgery, Vol. 28, No. 7, 2002, pp.

1088-1091. doi:10.1016/S0886-3350(02)01331-7

[3] G. Beltrame, M. L. Salvetat, M. Chizzolini, G. B. Driussi,

P. Busatto, G. Di Giorgio, F. Barosco and B. Scuderi,

“Implantation of A. Black Diaphragm Intraocular Lens in

Ten Cases of Post-Traumatic Aniridia,” European Jour-

nal of Ophthalmology, Vol. 13, No. 1, 2003, pp. 62-68.

[4] J. L. Menezo, R. Martínez-Costa, A. Cisneros and M. C.

Desco, “Implantation of Iris Devices in Congenital and

Traumatic Aniridias: Surgery Solutions and Complica-

tions,” European Journal of Ophthalmology, Vol. 15, No.

4, 2005, pp. 451-457.

[5] N. A. Pozdeyeva, N. P. Pashtayev, V. P. Lukin and Y. N.

Batkov, “Artificial Iris-Lens Diaphragm in Reconstruc-

tive Surgery for Aniridia and Aphakia,” Journal of Cata-

ract and Refractive Surgery, Vol. 31, No. 9, 2005, pp.

1750-1759. doi:10.1016/j.jcrs.2005.02.037

[6] R. S. Mashor, I. Bahar, I. Kaiserman, A. L. Berg, A.

Slomovic and D. S. Rootman, “Combined Penetrating

Keratoplasty and Implantation of Iris Prosthesis Intraocu-

lar Lenses after Ocular Trauma,” Journal of Cataract and

Refractive Surgery, Vol. 37, No. 3, 2011, pp. 582-587.

doi:/10.1016/j.jcrs.2010.10.038

[7] T. Kohnen, D. Kook, M. Morral and J. L. Güell, “Phakic

Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OJOph