Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

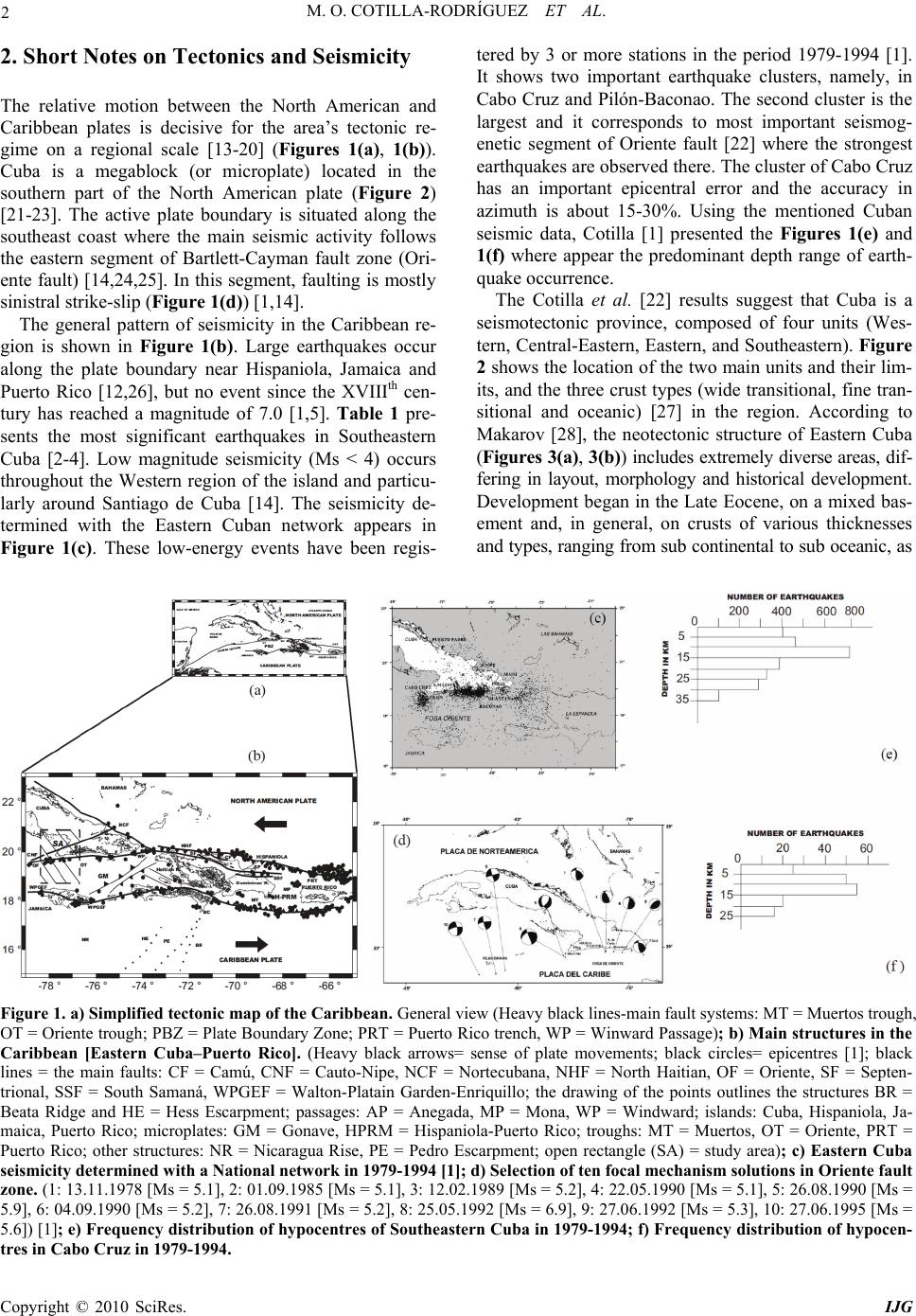

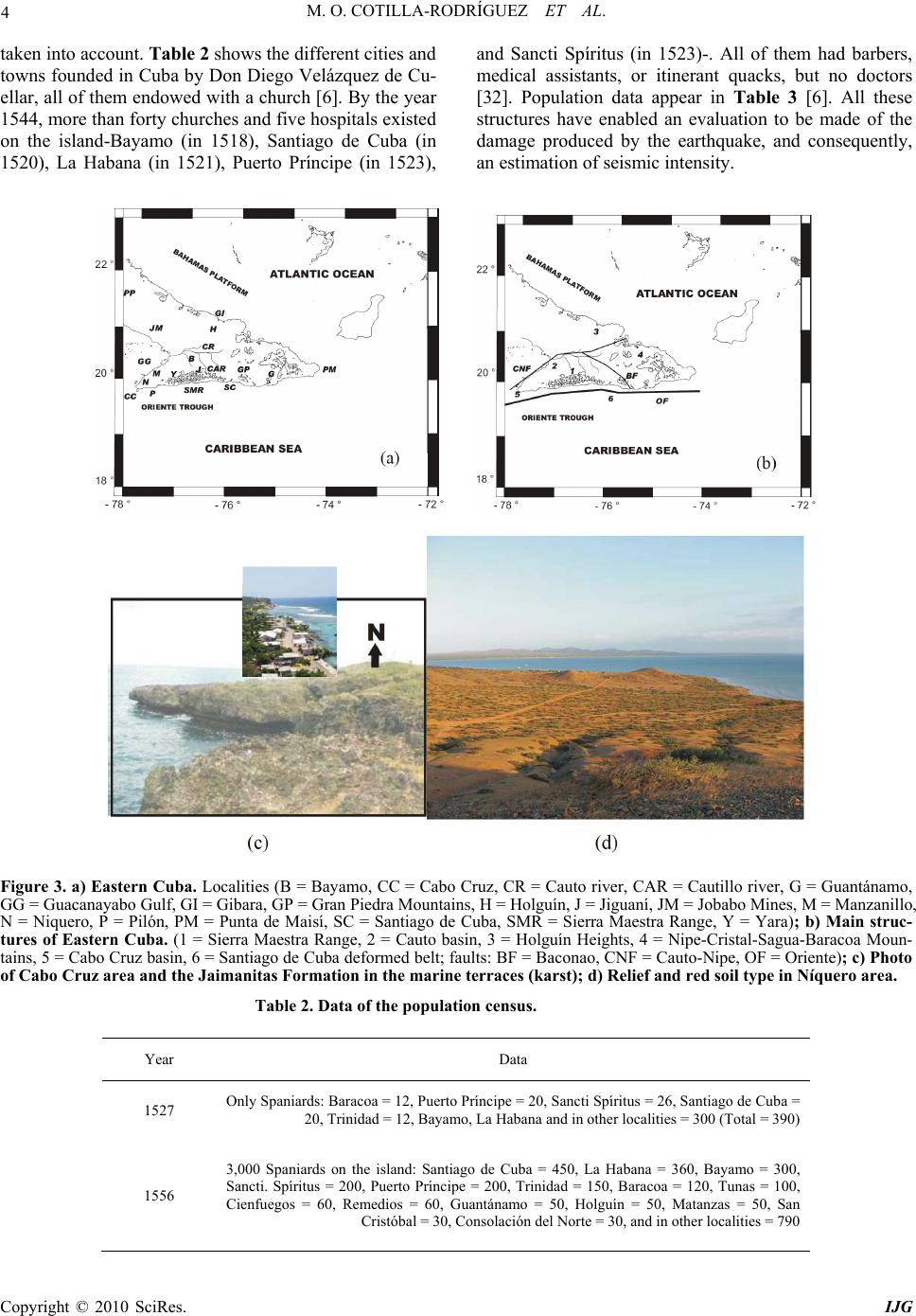

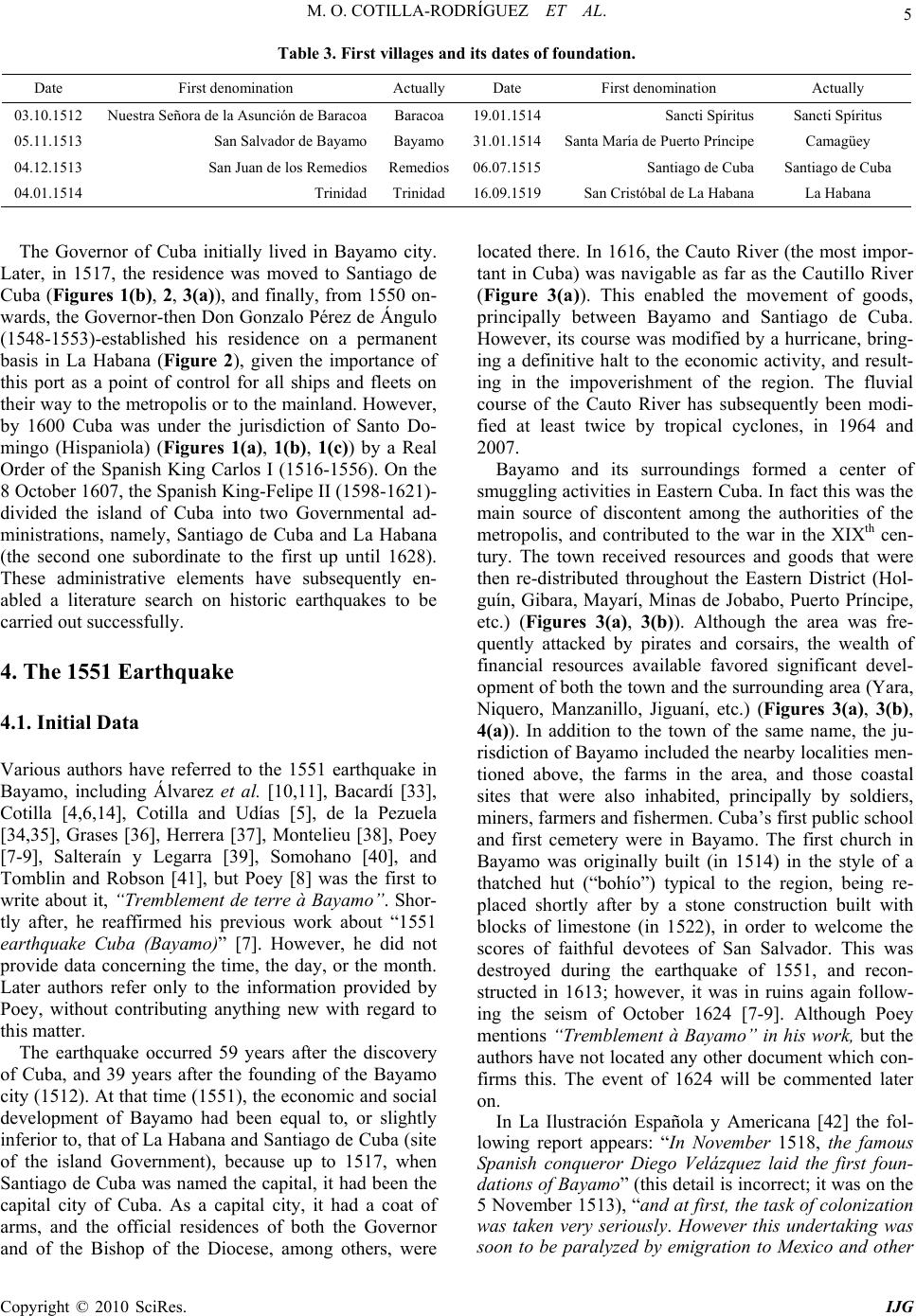

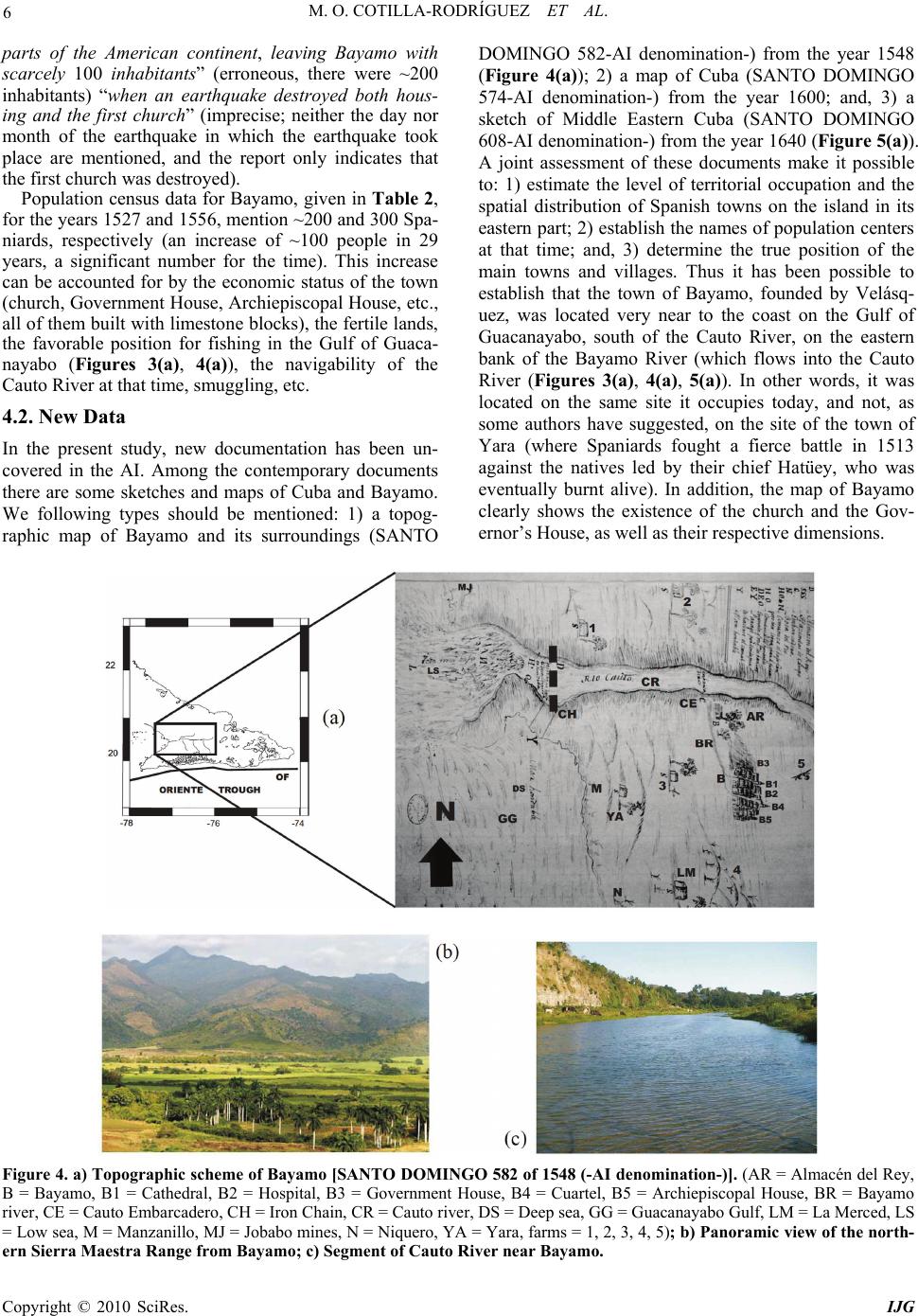

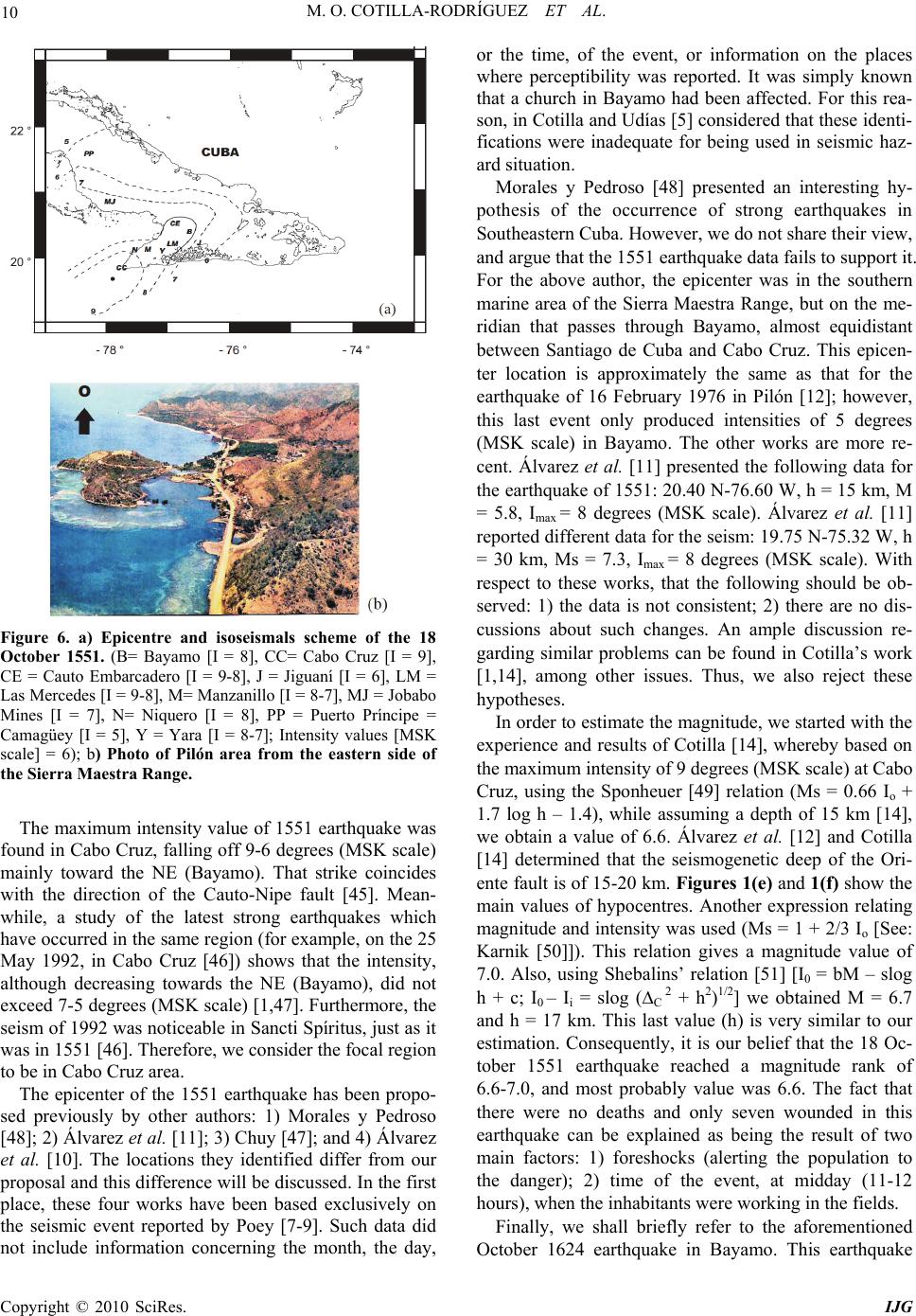

International Journal of Geosciences, 2010, 1-13 doi:10.4236/ijg.2010.11001 Published Online May 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ijg) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG The Bayamo Earthquake (Cuba) of the 18 October 1551 Mario O. Cotilla-Rodríguez, Diego Córdoba-Barba Departamento de Física de la Tierra y Astrofísica 1, Facultad de CC Físicas, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Ciudad Universitaria, Madrid, Spain E-mail: macot@fis.ucm.es, dcordoba@fis.ucm.es Received February 23, 2010; revised March 21, 2010; accepted April 20, 2010 Abstract Using contemporary and original documents from the Archivo General de Indias it has been possible to complete the data for the 18 October 1551 earthquake in Cuba. The seism took place at midday, approxi- mately. It had foreshocks and aftershocks. In Bayamo, 7 inhabitants were injured, and the town was severely affected. Maximum seismic intensity was IX degrees on the MSK scale, and the area of perceptibility is es- timated at 40,000 km2. Liquefaction processes and soil type in Bayamo contributed to the damage. This lo- cality is in the Eastern region of the island, and continues to suffer the most and the strongest seismic events. The epicenter was in the southern marine area of the western segment of Oriente trough (19.6 N 77.8 W, h = 15 km, Ms = 6.6), where there is a crossing of faults, and neotectonics and focal mechanisms are affected by transtension, although the Bartlett-Cayman region’s tendency to left-lateral strike-slip movement is main- tained, in the Caribbean and North American plate boundary zone. Keywords: Bayamo, Cuba, Earthquake, Historical Seismicity 1. Introduction In previous papers we have shown that relatively large and destructive earthquakes have occurred frequently in the past along the Oriente fault system [1,2]. We have also shown that American contemporary documents must be studied with care, in their historical and cultural con- text, in order to avoid overrating when evaluating inten- sity [3]. In this paper, we will discuss an historic Cuban earthquake, which occurred in the year 1551. The infor- mation for this seismic event comes from contemporary sources, such as unpublished consular correspondence, official documents and damage claims, as well as from the observations of travelers who passed through the epicentral region during and after the earthquake. An extensive literature search for documents relative to this earthquake was carried out in libraries and archives of Belgium, Cuba, Dominican Republic, England, France, Jamaica, Mexico, Spain, and United States of America. Cuba’s written history is fairly extensive. It began in 1492 with the diaries of the first Spanish explorers [4,5]. The Spanish colonizers and priests established Catholic churches throughout the island, in all the villages founded from 1512 onwards. Many of these documents are avail- able in the Archivo General de Indias (AI), Spain. Con- sultation at the AI enabled access to the original sources of information, for the first time, revealing that informa- tion on many XVIth century earthquakes has been com- piled. Cotilla [3] and Cotilla and Córdoba [2] have al- ready shown the usefulness of the AI, in the studies of four earthquakes in Santiago de Cuba. In 1687, Cuban newspapers were published for the first time, initially issued in Santiago de Cuba and La Habana [5,6]. They mentioned perceptible earthquakes, continued to spread across the Eastern Cuban region as the population increased. Descriptions of the Cuban earthquakes were catalogued by Poey [7-9], and were later interpreted in terms of shaking intensity, and later, earthquake epicenters and magnitude [10-12]. Cotilla and Udías [5] classify the earthquake information quality of the works by Andrés Poey y Aguirre, concluding that the information given for the event of 1551 in Bayamo is unsatisfactory. The aim of this paper is to detail what is known about the 1551 Cuban earthquake (Bayamo) including its sequ- ences, the location of the epicentral areas, assessment of magnitude, and its effects both on the ground and on man- made structures. A further aim is to provide a critical review of the information available and to resolve some ambiguities appearing in previous works. Attempts are made to associate these events with local tectonics or to evaluate the associated seismic hazard.  2 M. O. COTILLA-RODRÍGUEZ ET AL. 2. Short Notes on Tectonics and Seismicity The relative motion between the North American and Caribbean plates is decisive for the area’s tectonic re- gime on a regional scale [13-20] (Figures 1(a), 1(b)). Cuba is a megablock (or microplate) located in the southern part of the North American plate (Figure 2) [21-23]. The active plate boundary is situated along the southeast coast where the main seismic activity follows the eastern segment of Bartlett-Cayman fault zone (Ori- ente fault) [14,24,25]. In this segment, faulting is mostly sinistral strike-slip (Figure 1(d)) [1,14]. The general pattern of seismicity in the Caribbean re- gion is shown in Figure 1(b). Large earthquakes occur along the plate boundary near Hispaniola, Jamaica and Puerto Rico [12,26], but no event since the XVIIIth cen- tury has reached a magnitude of 7.0 [1,5]. Table 1 pre- sents the most significant earthquakes in Southeastern Cuba [2-4]. Low magnitude seismicity (Ms < 4) occurs throughout the Western region of the island and particu- larly around Santiago de Cuba [14]. The seismicity de- termined with the Eastern Cuban network appears in Figure 1(c). These low-energy events have been regis- tered by 3 or more stations in the period 1979-1994 [1]. It shows two important earthquake clusters, namely, in Cabo Cruz and Pilón-Baconao. The second cluster is the largest and it corresponds to most important seismog- enetic segment of Oriente fault [22] where the strongest earthquakes are observed there. The cluster of Cabo Cruz has an important epicentral error and the accuracy in azimuth is about 15-30%. Using the mentioned Cuban seismic data, Cotilla [1] presented the Figures 1(e) and 1(f) where appear the predominant depth range of earth- quake occurrence. The Cotilla et al. [22] results suggest that Cuba is a seismotectonic province, composed of four units (Wes- tern, Central-Eastern, Eastern, and Southeastern). Figure 2 shows the location of the two main units and their lim- its, and the three crust types (wide transitional, fine tran- sitional and oceanic) [27] in the region. According to Makarov [28], the neotectonic structure of Eastern Cuba (Figures 3(a), 3(b)) includes extremely diverse areas, dif- fering in layout, morphology and historical development. Development began in the Late Eocene, on a mixed bas- ement and, in general, on crusts of various thicknesses and types, ranging from sub continental to sub oceanic, as Figure 1. a) Simplified tectonic map of the Caribbean. General view (Heavy black lines-main fault systems: MT = Muertos trough, OT = Oriente trough; PBZ = Plate Boundary Zone; PRT = Puerto Rico trench, WP = Winward Passage); b) Main structures in the Caribbean [Eastern Cuba–Puerto Rico]. (Heavy black arrows= sense of plate movements; black circles= epicentres [1]; black lines = the main faults: CF = Camú, CNF = Cauto-Nipe, NCF = Nortecubana, NHF = North Haitian, OF = Oriente, SF = Septen- trional, SSF = South Samaná, WPGEF = Walton-Platain Garden-Enriquillo; the drawing of the points outlines the structures BR = Beata Ridge and HE = Hess Escarpment; passages: AP = Anegada, MP = Mona, WP = Windward; islands: Cuba, Hispaniola, Ja- maica, Puerto Rico; microplates: GM = Gonave, HPRM = Hispaniola-Puerto Rico; troughs: MT = Muertos, OT = Oriente, PRT = Puerto Rico; other structures: NR = Nicaragua Rise, PE = Pedro Escarpment; open rectangle (SA) = study area); c) Eastern Cuba seismicity determined with a National network in 1979-1994 [1]; d) Selection of ten focal mechanism solutions in Oriente fault zone. (1: 13.11.1978 [Ms = 5.1], 2: 01.09.1985 [Ms = 5.1], 3: 12.02.1989 [Ms = 5.2], 4: 22.05.1990 [Ms = 5.1], 5: 26.08.1990 [Ms = 5.9], 6: 04.09.1990 [Ms = 5.2], 7: 26.08.1991 [Ms = 5.2], 8: 25.05.1992 [Ms = 6.9], 9: 27.06.1992 [Ms = 5.3], 10: 27.06.1995 [Ms = 5.6]) [1]; e) Frequency distribution of hypocentres of Southeastern Cuba in 1979-1994; f) Frequency distribution of hypocen- tres in Cabo Cruz in 1979-1994. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG  M. O. COTILLA-RODRÍGUEZ ET AL. 3 Table 1. The most significant earthquakes in southeastern Cuba. Date/ Locality Coordinates/ Depth (km) Magnitude/ Intensity (MSK) Fatalities/ Injured 11.06.1766/S.Cuba 19.9N,-76.1W/25 6.8/IX 34/700 20.08.1852/S. Cuba 19.75N,-75.32W/30 6.4/VIII 2/200 03.02.1932/S. Cuba 19.75N,-75.58W/35-40 6.75/VIII 14/300 Figure 2. Cuban megablock according with Cotilla et al. [22]. (Heavy black line = faults: CNF = Cauto-Nipe, NCF = Nortecubana, OF = Oriente, SCF = Surcubana; Neotectonic Unit: OC = Western, OR = Eastern; crust type: 1 = post-orogenic complex, 2 = oro- genic complex, 3 = volcanic arc complex; localities: CC = Cabo Cruz, CS = Cabo de San Antonio, LH = La Habana, PM = Punta de Maisí, SC = Santiago de Cuba). established by Prol et al. [27]. The evolution of this structure was associated with, and considerably influ- enced by, deep-water troughs such as the Yucatan basin in the southwest, the Old Bahamas Channel in the north- east, and the Oriente trough in the south (Figure 1(a)). Sierra Maestra Range (h = 1,974 m) (Figures 3(a), 3(b)) has a simple structure [21,29]. Overall, it is an asymmetric swell, derived from an anticlinorium which was formed in the concluding phase of sheet folding in the Late Eocene. Its southern limb is cut off by a series of stepped faults from a deep-water trench (the Oriente trough) and is shifted eastward (Figure 3(b)). The relief in this area has a range of up to 10 km, with an average slope dip of up to 16º. On the northern limb the relief varies by about 2 km and the slope, by 3º-5º. Some geo- morphologic characteristics [30] indicate that the north- ern limb is also deformed, and sub latitudinal uplift zones successively decreasing in size from south to north can be identified within it. The largest newly generated neotectonic element in the structure of Eastern Cuba is the Cauto-Nipe syncli- norium system. It developed in association with the Si- erra Maestra Range, but is not a piedmont downward in the strict sense of the term [21,30]. According to Mann and Burke [25], the Cauto area constitutes a pull-apart basin, and the city of Bayamo is located within it (Fig- ures 3(a), 4(a)). The zone where it is located is charac- terized by significant layers of sediments form the Cauto- Nipe basin [21,30,31] (Figure 4(b)), something which evidently favors the amplification of the ground oscilla- tions. Cabo Cruz, in the eastern end of Southeastern Cuba (Figures 3(a), 3(b)), was discovered and named by Cristóbal Colón on 3 May 1494, during his second jour- ney. It is a coastal bar with marine terraces of up to 190 m in altitude and approximately 120 km2 (Figure 3(c)) [29]. It is some 30 km from Niquero (Figure 3(d)). This latter location and its surroundings, constitutes a region of plains neighboring the Gulf of Guacanayabo, into which the rivers of the northwest Sierra Maestra flow. The Cabo Cruz submarine area was studied tectonically by Calais and Mercier de Lèpinay [24], who concluded that it is a narrow E-W trending depression, bordered to the north and south by equal numbers of Oriente fault seg- ments. These comprise a set of horst-grabens inside a discontinuous trace of the Oriente fault system. 3. Some General Cuban Data Cuba was discovered in 1492 by Cristóbal Colón; how- ever it was not until 1512 that the Spanish became estab- lished there. To understand the importance of the earth- quake under discussion and the information contained in contemporary documents, the historical and demographic situation of Cuba, and in particular of Bayamo, must be Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG  4 M. O. COTILLA-RODRÍGUEZ ET AL. taken into account. Table 2 shows the different cities and towns founded in Cuba by Don Diego Velázquez de Cu- ellar, all of them endowed with a church [6]. By the year 1544, more than forty churches and five hospitals existed on the island-Bayamo (in 1518), Santiago de Cuba (in 1520), La Habana (in 1521), Puerto Príncipe (in 1523), and Sancti Spíritus (in 1523)-. All of them had barbers, medical assistants, or itinerant quacks, but no doctors [32]. Population data appear in Table 3 [6]. All these structures have enabled an evaluation to be made of the damage produced by the earthquake, and consequently, an estimation of seismic intensity. Figure 3. a) Eastern Cuba. Localities (B = Bayamo, CC = Cabo Cruz, CR = Cauto river, CAR = Cautillo river, G = Guantánamo, GG = Guacanayabo Gulf, GI = Gibara, GP = Gran Piedra Mountains, H = Holguín, J = Jiguaní, JM = Jobabo Mines, M = Manzanillo, N = Niquero, P = Pilón, PM = Punta de Maisí, SC = Santiago de Cuba, SMR = Sierra Maestra Range, Y = Yara); b) Main struc- tures of Eastern Cuba. (1 = Sierra Maestra Range, 2 = Cauto basin, 3 = Holguín Heights, 4 = Nipe-Cristal-Sagua-Baracoa Moun- tains, 5 = Cabo Cruz basin, 6 = Santiago de Cuba deformed belt; faults: BF = Baconao, CNF = Cauto-Nipe, OF = Oriente); c) Photo of Cabo Cruz area and the Jaimanitas Formation in the marine terraces (karst); d) Relief and red soil type in Níquero area. Table 2. Data of the population census. Year Data 1527 Only Spaniards: Baracoa = 12, Puerto Príncipe = 20, Sancti Spíritus = 26, Santiago de Cuba = 20, Trinidad = 12, Bayamo, La Habana and in other localities = 300 (Total = 390) 1556 3,000 Spaniards on the island: Santiago de Cuba = 450, La Habana = 360, Bayamo = 300, Sancti. Spíritus = 200, Puerto Príncipe = 200, Trinidad = 150, Baracoa = 120, Tunas = 100, Cienfuegos = 60, Remedios = 60, Guantánamo = 50, Holguín = 50, Matanzas = 50, San Cristóbal = 30, Consolación del Norte = 30, and in other localities = 790 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG  M. O. COTILLA-RODRÍGUEZ ET AL. 5 Table 3. First villages and its dates of foundation. Date First denomination Actually Date First denomination Actually 03.10.1512Nuestra Señora de la Asunción de BaracoaBaracoa 19.01.1514Sancti Spíritus Sancti Spíritus 05.11.1513San Salvador de Bayamo Bayamo 31.01.1514Santa María de Puerto PríncipeCamagüey 04.12.1513San Juan de los Remedios Remedios06.07.1515Santiago de Cuba Santiago de Cuba 04.01.1514 Trinidad Trinidad 16.09.1519San Cristóbal de La Habana La Habana The Governor of Cuba initially lived in Bayamo city. Later, in 1517, the residence was moved to Santiago de Cuba (Figures 1(b), 2, 3(a) ), and finally, from 1550 on- wards, the Governor-then Don Gonzalo Pérez de Ángulo (1548-1553)-established his residence on a permanent basis in La Habana (Figure 2), given the importance of this port as a point of control for all ships and fleets on their way to the metropolis or to the mainland. However, by 1600 Cuba was under the jurisdiction of Santo Do- mingo (Hispaniola) (Figures 1(a), 1(b), 1( c) ) by a Real Order of the Spanish King Carlos I (1516-1556). On the 8 October 1607, the Spanish King-Felipe II (1598-1621)- divided the island of Cuba into two Governmental ad- ministrations, namely, Santiago de Cuba and La Habana (the second one subordinate to the first up until 1628). These administrative elements have subsequently en- abled a literature search on historic earthquakes to be carried out successfully. 4. The 1551 Earthquake 4.1. Initial Data Various authors have referred to the 1551 earthquake in Bayamo, including Álvarez et al. [10,11], Bacardí [33], Cotilla [4,6,14], Cotilla and Udías [5], de la Pezuela [34,35], Grases [36], Herrera [37], Montelieu [38], Poey [7-9], Salteraín y Legarra [39], Somohano [40], and Tomblin and Robson [41], but Poey [8] was the first to write about it, “Tremblement de terre à Bayamo”. Shor- tly after, he reaffirmed his previous work about “1551 earthquake Cuba (Bayamo)” [7]. However, he did not provide data concerning the time, the day, or the month. Later authors refer only to the information provided by Poey, without contributing anything new with regard to this matter. The earthquake occurred 59 years after the discovery of Cuba, and 39 years after the founding of the Bayamo city (1512). At that time (1551), the economic and social development of Bayamo had been equal to, or slightly inferior to, that of La Habana and Santiago de Cuba (site of the island Government), because up to 1517, when Santiago de Cuba was named the capital, it had been the capital city of Cuba. As a capital city, it had a coat of arms, and the official residences of both the Governor and of the Bishop of the Diocese, among others, were located there. In 1616, the Cauto River (the most impor- tant in Cuba) was navigable as far as the Cautillo River (Figure 3(a)). This enabled the movement of goods, principally between Bayamo and Santiago de Cuba. However, its course was modified by a hurricane, bring- ing a definitive halt to the economic activity, and result- ing in the impoverishment of the region. The fluvial course of the Cauto River has subsequently been modi- fied at least twice by tropical cyclones, in 1964 and 2007. Bayamo and its surroundings formed a center of smuggling activities in Eastern Cuba. In fact this was the main source of discontent among the authorities of the metropolis, and contributed to the war in the XIXth cen- tury. The town received resources and goods that were then re-distributed throughout the Eastern District (Hol- guín, Gibara, Mayarí, Minas de Jobabo, Puerto Príncipe, etc.) (Figures 3(a), 3(b)). Although the area was fre- quently attacked by pirates and corsairs, the wealth of financial resources available favored significant devel- opment of both the town and the surrounding area (Yara, Niquero, Manzanillo, Jiguaní, etc.) (Figures 3(a), 3(b), 4(a)). In addition to the town of the same name, the ju- risdiction of Bayamo included the nearby localities men- tioned above, the farms in the area, and those coastal sites that were also inhabited, principally by soldiers, miners, farmers and fishermen. Cuba’s first public school and first cemetery were in Bayamo. The first church in Bayamo was originally built (in 1514) in the style of a thatched hut (“bohío”) typical to the region, being re- placed shortly after by a stone construction built with blocks of limestone (in 1522), in order to welcome the scores of faithful devotees of San Salvador. This was destroyed during the earthquake of 1551, and recon- structed in 1613; however, it was in ruins again follow- ing the seism of October 1624 [7-9]. Although Poey mentions “Tremblement à Bayamo” in his work, but the authors have not located any other document which con- firms this. The event of 1624 will be commented later on. In La Ilustración Española y Americana [42] the fol- lowing report appears: “In November 1518, the famous Spanish conqueror Diego Velázquez laid the first foun- dations of Bayamo” (this detail is incorrect; it was on the 5 November 1513), “and at first, the task of colonization was taken very seriously. However this undertaking was soon to be paralyzed by emigration to Mexico and other Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG  6 M. O. COTILLA-RODRÍGUEZ ET AL. parts of the American continent, leaving Bayamo with scarcely 100 inhabitants” (erroneous, there were ~200 inhabitants) “when an earthquake destroyed both hous- ing and the first church” (imprecise; neither the day nor month of the earthquake in which the earthquake took place are mentioned, and the report only indicates that the first church was destroyed). Population census data for Bayamo, given in Table 2, for the years 1527 and 1556, mention ~200 and 300 Spa- niards, respectively (an increase of ~100 people in 29 years, a significant number for the time). This increase can be accounted for by the economic status of the town (church, Government House, Archiepiscopal House, etc., all of them built with limestone blocks), the fertile lands, the favorable position for fishing in the Gulf of Guaca- nayabo (Figures 3(a), 4(a)), the navigability of the Cauto River at that time, smuggling, etc. 4.2. New Data In the present study, new documentation has been un- covered in the AI. Among the contemporary documents there are some sketches and maps of Cuba and Bayamo. We following types should be mentioned: 1) a topog- raphic map of Bayamo and its surroundings (SANTO DOMINGO 582-AI denomination-) from the year 1548 (Figure 4(a)); 2) a map of Cuba (SANTO DOMINGO 574-AI denomination-) from the year 1600; and, 3) a sketch of Middle Eastern Cuba (SANTO DOMINGO 608-AI denomination-) from the year 1640 (Figure 5(a)). A joint assessment of these documents make it possible to: 1) estimate the level of territorial occupation and the spatial distribution of Spanish towns on the island in its eastern part; 2) establish the names of population centers at that time; and, 3) determine the true position of the main towns and villages. Thus it has been possible to establish that the town of Bayamo, founded by Velásq- uez, was located very near to the coast on the Gulf of Guacanayabo, south of the Cauto River, on the eastern bank of the Bayamo River (which flows into the Cauto River (Figures 3(a), 4(a), 5(a)). In other words, it was located on the same site it occupies today, and not, as some authors have suggested, on the site of the town of Yara (where Spaniards fought a fierce battle in 1513 against the natives led by their chief Hatüey, who was eventually burnt alive). In addition, the map of Bayamo clearly shows the existence of the church and the Gov- ernor’s House, as well as their respective dimensions. Figure 4. a) Topographic scheme of Bayamo [SANTO DOMINGO 582 of 1548 (-AI denomination-)]. (AR = Almacén del Rey, B = Bayamo, B1 = Cathedral, B2 = Hospital, B3 = Government House, B4 = Cuartel, B5 = Archiepiscopal House, BR = Bayamo river, CE = Cauto Embarcadero, CH = Iron Chain, CR = Cauto river, DS = Deep sea, GG = Guacanayabo Gulf, LM = La Merced, LS = Low sea, M = Manzanillo, MJ = Jobabo mines, N = Niquero, YA = Yara, farms = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5); b) Panoramic view of the north- ern Sierra Maestra Range from Bayamo; c) Segment of Cauto River near Bayamo. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG  M. O. COTILLA-RODRÍGUEZ ET AL. 7 Figure 5. a) Map of the Eastern Cuba [SANTO DOMINGO 608 of 1640 (-AI denomination-)]. See Figure 3(a). (B= Bayamo, BA = Baracoa, BC= Baconao, CAS= Cascorro, CC= Cabo Cruz, CO = El Cobre, G= Guantánamo, GG= Guacanayabo Gulf, H= Holguín, J= Jiguaní, M= Manzanillo, MA= Mayarí, MJ= Jobabo mines, N= Niquero, PP= Puerto Príncipe= Camagüey, PPA= Puerto Padre, SC= Santiago de Cuba, SL= San Luis, SMR= Sierra Maestra Range, SS= Sancti Spiritus, ST= Sagua de Tánamo, Y= Yara); b) Photo of the relief and rock types in San Luis area; c) View of Manzanillo and Guacanayabo Gulf areas; d) View from Las Mercedes to northern of Sierra Maestra Range; e) Photo of a mountain river in Jiguaní. The map of 1548 (SANTO DOMINGO 582) (Figure 4(a)) shows, among other things: 1) the dimension of the Cauto River and its navigability upstream, including be- yond the town of Bayamo; 2) the town of Bayamo, to- gether with the Cathedral, the Governor’s House, and the residential neighborhoods; 3) the river port (today Cauto Embarcadero); 4) the King’s Storehouse; and, 5) five farms; etc. This geographic position for Bayamo is sup- ported by the fact that the town would thus have had di- rect access to the sea (the Gulf of Guacanayabo) close to the mouth of the Cauto River, making navigation inland feasible even as far as Jiguaní (Figures 3(a), 5(a)), and from there the journey to Santiago de Cuba by road was relatively flat and straightforward, continuing as far as San Luis (Figures 5(a), 5(b)). It should be mentioned that between the XVIth and XIXth centuries, at least 10 maps that include the island of Cuba have been edited [43], and the scientific works of the following authors can be cited: 1) Juan de la Cosa (in 1500); 2) Abraham Ortelieus (in 1580); 3) Heyro- nymi Benzoni (in 1594); 4) Guiljelmus Blaen (in 1638); 5) N. Sanson d’Abbuille (in 1656); 6) Pieter Vander A. A. (in 1728); and 7) Esteban Pichardo (in 1855). In gen- eral the cartography of these maps improves with suc- cessive editions. However, the map of 1728 has serious errors still, for example: 1) placing Bayamo city in Hol- guín area (Figures 3(a), 5(a)); 2) denominating the Cauto River as the Zaza River (which is in the Central region of the island). Even at that time, Guantánamo (Figures 3(a), 5(a)) was being called Puerto Grande. In the year 1638, the Cauto River was designated on the map as the Bahamas River, and on the same map, the town of Manzanillo (Figures 3(a), 4(a), 5(a), 5(c)) ap- pears for the first time. With regard to the cartographic deficiencies in the maps of Cuba, Pichardo [44] com- mented: “many earlier and current maps have been compiled by people who have not so much as stepped on Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG  8 M. O. COTILLA-RODRÍGUEZ ET AL. Cuban territory…” Such comment explains all deficien- cies in the mentioned Cuban maps. The three maps located by the authors in the AI were drawn up in 1548-1640 and it can be seen that the con- tents are similar to those of maps 2-4 mentioned above. However, the geographic position of Cuban localities given in the materials located in the AI is considerably more accurate than that given in map number 7 (by Pich- ardo). We are of the opinion that this is due to the fact that they were the work of specialists who were familiar with the territory that they represented, and are therefore reliable. In addition four contemporary hand-written documents relating to the earthquake of 1551 have been located in the AI. A summary of these materials follows: (Document 1.-) GOVERNMENT PAPERS: 1492- 1858. SANTO DOMINGO, JUDICIAL DISTRICTS: 1511, 1512-1858 [-AI denomination-]. (Correspondence of Don Juan de Hiniestrosa, Governor of the village of San Salvador de Bayamo, with Don Gonzalo Pérez de Ángulo, Governor of Cuba) San Salvador de Bayamo, 28 Octubre 1551 His Excellency, Don Gonzalo Pérez de Ángulo General Governor of Cuba It is my duty to inform your Excellency of the events which took place on the 18th (according to the date in the wording of the document, October 1551) in San Salvador de Bayamo. Close to midday (11-12 o’clock), work was interrupted by a dreadful shake (the main earthquake). Many have been injured, and the town has suffered seri- ous damage… (There were no deaths)… The principal and most severe damage was sustained by the solid and regal barracks, which collapsed, with one person being injured. The Parochial Church which adjoins the bar- racks, and the hospital (Figure 4(a)), were completely destroyed… all the farms (according to the 1548 map, there were farms to the south and north of the Cauto River, in the area around Bayamo) suffered severe dam- age as a result of the violence of the movements of the earth… (Destruction)… in the town, on the 18th day at midday, terror struck in the hearts of the men and women laboring in the fields. Beasts fled, sixteen houses in the village collapsed, and another three, although still stand- ing, have huge cracks in their walls… two wounded were found… the Embarcadero (on the south bank of the River Cauto, today called Cauto Embarcadero, Figure 4(a)) was destroyed, causing damage to four ships and injuring two people… the Church, built of solid stone, has been completely destroyed, the central pillars hang by a miracle… the barracks collapsed, and one person was injured… the stables fell… the prison and the hos- pital are in ruins… the well in the Square has col- lapsed… five houses on the riverside (Bayamo) were overturned and sank into the mud (liquefaction)… muddy, stinking water flowed from the banks of the river… beasts sprawled on the ground… The King’s Storehouse (on the southern bank of the Cauto River and to the east of the Embarcadero, Figure 4(a)) has been destroyed. All the merchandise and goods were lost… three canons and the defensive line of heavy iron chain (an army obstacle in the Cauto River which impeded the entry of enemy ships) have sunk into the mud… (lique- faction)… the land is fertile and flat, and the hills only rise in the distance, to the south as an enormous mass, the Gran Sierra (nowadays known as the Sierra Maestra Range [Figures 1(c), 3( a), 3(b), 4(b), 5(a)])… the oldest inhabitants here say that the plain here is different to that of Cuba (at that time, Santiago de Cuba was fre- quently referred to as Cuba, and vice versa), always jerking and shaking… the danger was not felt in Cuba… (Santiago de Cuba seismicity was perfectly well known, but in Bayamo any report)… the night was pitiful and cold...people kept vigil and there were sudden shocks (aftershocks)… a procession carried a statue of the Saintly and Divine Patron Saint (San Salvador) in their arms… the sub-lieutenant Fernando Rodríguez de Cas- tro returned from patrolling the hills to the south (Sierra Maestra Range) and from the coastal posts of Cabo Cruz, Niquero and La Costa (today Manzanillo) (Figures 3(a), 3(c), 5(a), 5(c)), with the garrison detachment. He re- ports that at midday on the 18th October, they noted the ground moving beneath their feet, and heard noises like thunder emanating from beneath the ground… the noises came from the south (Cabo Cruz), and huge, solid rocks could be seen strewn across the road to La Merced (in the mountainous part of the Sierra Maestra range, on the northern side, today Las Mercedes) (Figures 4(a), 5(d))… the beasts of burden refused to advance… the cracks in the road were 12 varas (~9 m) wide (1 Castil- lian vara = 0.8359 m)… two soldiers fell in their saddles to the ground… in Yara, all the houses, around twenty or more, were in ruins… the timbers and pillars scat- tered… (This town is on a low alluvial plain well irri- gated by fluvial currents from the Sierra Maestra. There- fore, it is highly probable that liquefaction occurred)… the sub-lieutenant ordered two soldiers to return at a gallop to the coastal posts (Cabo Cruz and Níquero [Figures 3(a), 3(d), 4(a), 5(d)]) in order to acquaint themselves of the situation there, whilst the rest marched to La Costa (Manzanillo)… they informed him that Cabo Cruz was in ruins… two canons were overturned… but that there had been no injuries… the posts at Níquero and La Costa (Manzanillo)… lost everything, and a sol- dier received a heavy blow when he fell… all canons were overturned… Jiguaní ([Figures 3(a), 5(a), 5(e)] town on the western bank of the Cautillo River) was fiercely and brutally shaken, and the houses ruined, the church and the heavy wood barracks destroyed… (the above-mentioned towns appear in Figure 3(a)) … on the night of the 16 th and the morning of the 17th, short, strong earth tremors had been noticed (fore- shocks)… the ground collapsed and moved like an angry sea… never before has such an event been heard of Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG  M. O. COTILLA-RODRÍGUEZ ET AL. 9 here… (Document 2.-) CUBA 2007 [-AI denomination-] San Salvador de Bayamo, 19 December 1551 His Excellency, Don Gonzalo Pérez de Ángulo General Governor of Cuba …with regard to the inspection of the barracks in this town of San Salvador de Bayamo, the captain Don Bar- tolomé Quesada de Castro was very surprised and sad- dened to see the serious damage caused to the town and the destruction of the barracks. He reports that in Sancti Spiritus and Jobabo Mines (Figures 3(a), 4(a), 5(a)) a strong earth tremor was felt at mid-morning (12 hours) on the 18th day (October) in the barracks. And in the neighboring town of Santa María de Puerto Príncipe (now Camagüey, [Figures 3(a), 5(a)]), the Garrison officer in command assured him that three strong earth tremors had been felt on the 18th and 19th at dinner time and at night… (The authors can confirm the occurrence on 18 October of an earthquake and of some aftershocks. In addition, information on perceptibility was gathered in Sancti Spíritus and Camagüey but any subterranean noise was perceptible [Figure 5(a)]). (Document 3.-) CUBA 2027 [-AI denomination-] San Salvador de Bayamo, 20 December 1551 His Excellency, Don Gonzalo Pérez de Ángulo General Governor of Cuba … I can report with pride of the Crown’s loyal troops, who have undertaken the repair of the coastal posts… [Cabo Cruz, Niquero and Manzanillo] (Document 4.-) CUBA 2070 [-AI denomination-] San Salvador de Bayamo, 14 February 1552 His Excellency, Don Gonzalo Pérez de Ángulo General Governor of Cuba …the town’s barracks have been rebuilt with timber, and one part serves as a jail. The troops are in good humor, and the terror is fading… 4.3. Earthquake Parameters and Intensity Values Identify the Headings Using these data (Documents 1-4) the authors have es- tablished that the town of San Salvador of Bayamo was located on the present site of Bayamo and not at Yara (Figures 3(a), 4(a), 5( a)) and since the foundation of the town in 1513, earthquakes had never previously been reported. In addition, it can be stated that: 1) the exact date of the occurrence of this earthquake was the 18 Oc- tober 1551; 2) the approximate time of the seismic event was around midday (11-12 hours); 3) there were at least two foreshocks, on the 16 and 17 October; 4) there were three aftershocks on the 18 October; 5) subterranean noises originating from the south-southwest, Cabo Cruz, were heard up to Bayamo city; 6) there were only seven persons injured, but no deaths; 7) there was panic among the population of Bayamo and alarm and nervousness among the beasts of burden in everywhere; 8) the army post at Cabo Cruz was destroyed and the two heavy cannons overturned, severe subterranean noises [I = 9 degrees, MSK]; 9) the greatest damage to the ground (cracks and large block rocks) was in the surrounding area of the Sierra Maestra Range (La Merced) and sol- diers were shaken in their saddles and two fell to the ground together with the saddles [I = 9-8 degrees, MSK]; 10) other two army posts in Niquero and Manzanillo were heavy damaged and all cannons overturned [I = 9-8 degrees, MSK]; 11) the church in Bayamo (built of solid limestone blocks) was totally destroyed, along with the residential neighborhood, the hospital, the jail, the store- house, and the dock [I = 8 degrees, MSK]; 12) the town at Cauto Embarcadero and four ships were totally de- stroyed (liquefaction) [I = 8 degrees, MSK]; 13) 21 houses were destroyed and 3 were severely damaged in Bayamo [I = 8 degrees, MSK]; 14) the farms (outside of Bayamo on the southern and northern banks of the Cauto River, but near to the town) were destroyed [I = 8-7 de- grees, MSK]; 15) over 20 robust houses (heavy woods) were destroyed in Yara (probably due to liquefaction) [I = 8-7 degrees, MSK]; 16) there were several houses de- stroyed in Jiguaní [I = 6 degrees, MSK]; 17) Puerto Prín- cipe village (Camagüey) was very strong shacked [I = 5 degrees, MSK]; 18) in Sancti Spíritus the earthquake was perceptible [I = 3 degrees, MSK]. We must comment that the intensity values of 8 and 9-8 degrees (MSK scale) in Bayamo, Cauto Embarcad- ero, and Niquero (and it can be assumed also in the King’s Storehouse) is explained by the liquefaction phe- nomena and site effects. That means there are uncon- solidated soils in a large fluvial basin (Cauto-Nipe). This is not the case of Cabo Cruz area. Using these references, it is possible to construct an isoseismal scheme (Figure 6(a)), and to estimate a per- ceptibility area of 40,000 km2. Then taking the area of greatest value as the central point and as the starting poi- nt for a line extending offshore to the south, the ap- proximate epicentral location can be estimated as 19.6 N -77.8 W, which is situated on the knot of faults previ- ously mentioned (Figure 2). In addition, this location has a cluster of low magnitude earthquakes with a predomi- nant depth of 15 km (Figures 1(e), 1(f)) [1,14]. But there were also strong earthquakes in the surrounding area in October 1624 and on the 03.08.1926 [12]; more re- cently, other five strong earthquakes have been regis- tered [19.02.1976 (Pilón, M = 5.7), 12.02.1989 (M = 5.1), 26.08.1990 (M = 5.1), 25.05.1992 (M = 6.9), and 04.02.2007 (M = 6.2), h~15 km] [6]. These earthquakes, except the one in Pilón (Figure 6(b)), are delimited by crossing active faults (Oriente and Cauto-Nipe) in the marine area. This is to the NE of the Cabo Cruz basin (in the marine area). Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG  10 M. O. COTILLA-RODRÍGUEZ ET AL. Figure 6. a) Epicentre and isoseismals scheme of the 18 October 1551. (B= Bayamo [I = 8], CC= Cabo Cruz [I = 9], CE = Cauto Embarcadero [I = 9-8], J = Jiguaní [I = 6], LM = Las Mercedes [I = 9-8], M= Manzanillo [I = 8-7], MJ = Jobabo Mines [I = 7], N= Niquero [I = 8], PP = Puerto Príncipe = Camagüey [I = 5], Y = Yara [I = 8-7]; Intensity values [MSK scale] = 6); b) Photo of Pilón area from the eastern side of the Sierra Maestra Range. The maximum intensity value of 1551 earthquake was found in Cabo Cruz, falling off 9-6 degrees (MSK scale) mainly toward the NE (Bayamo). That strike coincides with the direction of the Cauto-Nipe fault [45]. Mean- while, a study of the latest strong earthquakes which have occurred in the same region (for example, on the 25 May 1992, in Cabo Cruz [46]) shows that the intensity, although decreasing towards the NE (Bayamo), did not exceed 7-5 degrees (MSK scale) [1,47]. Furthermore, the seism of 1992 was noticeable in Sancti Spíritus, just as it was in 1551 [46]. Therefore, we consider the focal region to be in Cabo Cruz area. The epicenter of the 1551 earthquake has been propo- sed previously by other authors: 1) Morales y Pedroso [48]; 2) Álvarez et al. [11]; 3) Chuy [47]; and 4) Álvarez et al. [10]. The locations they identified differ from our proposal and this difference will be discussed. In the first place, these four works have been based exclusively on the seismic event reported by Poey [7-9]. Such data did not include information concerning the month, the day, or the time, of the event, or information on the places where perceptibility was reported. It was simply known that a church in Bayamo had been affected. For this rea- son, in Cotilla and Udías [5] considered that these identi- fications were inadequate for being used in seismic haz- ard situation. Morales y Pedroso [48] presented an interesting hy- pothesis of the occurrence of strong earthquakes in Southeastern Cuba. However, we do not share their view, and argue that the 1551 earthquake data fails to support it. For the above author, the epicenter was in the southern marine area of the Sierra Maestra Range, but on the me- ridian that passes through Bayamo, almost equidistant between Santiago de Cuba and Cabo Cruz. This epicen- ter location is approximately the same as that for the earthquake of 16 February 1976 in Pilón [12]; however, this last event only produced intensities of 5 degrees (MSK scale) in Bayamo. The other works are more re- cent. Álvarez et al. [11] presented the following data for the earthquake of 1551: 20.40 N-76.60 W, h = 15 km, M = 5.8, Imax = 8 degrees (MSK scale). Álvarez et al. [11] reported different data for the seism: 19.75 N-75.32 W, h = 30 km, Ms = 7.3, Imax = 8 degrees (MSK scale). With respect to these works, that the following should be ob- served: 1) the data is not consistent; 2) there are no dis- cussions about such changes. An ample discussion re- garding similar problems can be found in Cotilla’s work [1,14], among other issues. Thus, we also reject these hypotheses. In order to estimate the magnitude, we started with the experience and results of Cotilla [14], whereby based on the maximum intensity of 9 degrees (MSK scale) at Cabo Cruz, using the Sponheuer [49] relation (Ms = 0.66 Io + 1.7 log h – 1.4), while assuming a depth of 15 km [14], we obtain a value of 6.6. Álvarez et al. [12] and Cotilla [14] determined that the seismogenetic deep of the Ori- ente fault is of 15-20 km. Figures 1(e) and 1(f) show the main values of hypocentres. Another expression relating magnitude and intensity was used (Ms = 1 + 2/3 Io [See: Karnik [50]]). This relation gives a magnitude value of 7.0. Also, using Shebalins’ relation [51] [I0 = bM – slog h + c; I0 – Ii = slog (∆C 2 + h2)1/2] we obtained M = 6.7 and h = 17 km. This last value (h) is very similar to our estimation. Consequently, it is our belief that the 18 Oc- tober 1551 earthquake reached a magnitude rank of 6.6-7.0, and most probably value was 6.6. The fact that there were no deaths and only seven wounded in this earthquake can be explained as being the result of two main factors: 1) foreshocks (alerting the population to the danger); 2) time of the event, at midday (11-12 hours), when the inhabitants were working in the fields. Finally, we shall briefly refer to the aforementioned October 1624 earthquake in Bayamo. This earthquake Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG  M. O. COTILLA-RODRÍGUEZ ET AL. 11 happened 73 years after the event of 1551 and 8 years after closing the Cauto River to the navigation as a con- sequence of the damages by a strong tropical hurricane. Regardless of the scarce amount of data contributed by Poey, it is possible to assert the following concerning the earthquake: 1) the important intensity value of the seismic event; 2) the repetition of large earthquakes in the Cauto zone; 3) Bayamo’s cost-reducing decrease and in conse- quence the low interest of the authorities, once the mi- gration had started toward Santiago de Cuba and La Ha- bana, and the Governor Residence had changed to La Habana. Likewise, it can be assumed that: 1) the dam- ages at the Cathedral of Bayamo were due to the combi- nation of two adverse factors, soil type and soil condi- tions; 2) the earthquake focus was located in the same region at 1551. 5. Conclusions Eastern Cuba suffered a strong earthquake at midday on the 18 October 1551. It has been possible to confirm this data based on a collection of unpublished documents and others in the Archivo General de Indias, thus improving knowledge on the seismicity of this territory. An analysis of historical sources has shown that documents need to be judged very critically, establishing which ones pro- vide first hand information and which more generalized literary accounts are. In addition, awareness of the so- cioeconomic situation, demographic conditions, building characteristics, etc. is necessary in order to reach a cor- rect damage assessment. Failure to take these considera- tions into account can lead to significant errors in inten- sity estimations with the consequent effect on seismic risk assessment. From the foregoing it appears that the 1551 earthquake was of a greater magnitude than believed until now. Ma- ximum damage was experienced along the Cauto-Nipe fault. There is conclusive field evidence to show that this earthquake was associated with surface faulting. As a result of the shocks, some areas surrounding Bayamo, as well as others at some distance away were intensely da- maged. From the description of the effects of the earth- quake, it is clear that liquefaction of the ground had a significant effect on damage and on the intensities as- signed to the Bayamo area. According to the information found in the documents, the damage caused by this earthquake may be summa- rized as follows (locality = Intensity, MSK scale): Cabo Cruz = 9, Sierra Maestra (Las Mercedes) = 9-8, Bayamo = 8, Cauto Embarcadero = 8, Niquero = 8, Yara = 8-7, Manzanillo = 8-7, Jobabo Mines = 7, Jiguaní = 6, Puerto Príncipe = 5, and Sancti Spíritus = 3. The earthquake reached a magnitude of 6.6 and the epicenter was situ- ated at 19.6 N-77.8 W. 6. Acknowledgements The authors wish to thank the Archivo General de Indias for providing important information and data. The effort and help by the responsible of the reading rooms and the specialists of the AI were decisive to culminate this work. Observations and suggestions made by Agustín Udías and Armando Cisternas allowed us to improve the man- uscript. This work has been partially funded by the REN2003-08520-C02-02, REN2002-12494E/RIES and CGL2005-25012-E. Access to facilities and information technology resources was made available to the authors by the Departamento de Física de la Tierra y Astrofísica 1, Facultad de Ciencias Físicas, Universidad Complute- nse de Madrid. 7. References [1] M. O. Cotilla, “An Overview on the Seismicity of Cuba,” Journal of Seismology, Vol. 2, No. 4, 1998, pp. 323-335. [2] M. Cotilla and D. Córdoba, “Notes on the Three Earth- quakes in Santiago de Cuba (14.10.1880, 18.09.1826, 07.07. 1842),” Russian Geology and Geophysics, Vol. 51, No. 2, 2010, pp. 228-236. [3] M. O. Cotilla, “The Santiago de Cuba Earthquake of 11th June 1766: Some new insights,” Geofísica Internacional, Vol. 42, No. 4, 2003, pp. 589-602. [4] M. O. Cotilla, “Cuban Seismology,” Revista Historia de América, Vol. 140, 2010. [5] M. Cotilla and A. Udías, “La Ciencia Sismológica en Cuba (II). Algunos Terremotos Históricos,” Revista de Historia de América, in Spanish, Vol. 125, 1999, pp. 45-90. [6] M. O. Cotilla, “Un recorridoPor La Sismología de Cuba,” Editorial Complutense, in Spanish, Madrid, 2007. [7] A. Poey, “Catalogue Chronologique des Tremblements de Terre Ressentis Dans Les Indes Occidentales de 1530 à 1857. Accompagnè d’ une revue bibliographique con- tenant tous les travaux relatifs aux tremblements de terre des Antilles,” Annuarie de la Societé Mété-orologique de France, in French, Vol. 5, 1857, pp. 75-227. [8] A. Poey, “Tableau Chronologique des Tremblements de Terre Resentís a l’ ile de Cuba de 1551 à 1855,” Annales des Voyages, in French, Vol. 11, 1855, p. 301. [9] A. Poey, “Supplément au Tableau Chronologique des Tremb-Lements de Terre Resentís à l’ ile de Cuba de 1530 à 1855,” Annales des Voyages, in French, Vol. 4, 1855A, p. 286. [10] L. Álvarez, T. Chuy, J. Garcia, B. Moreno, H. Álvarez, M. Blanco, O. Expósito, O. González and A. I. Fernández, “An Earthquake Catalogue of Cuba and Neighbouring Areas,” Internal Report IC/ IR/99/1, The Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics, Miramare, Trieste, 1999. [11] L. Álvarez, R. S. Mijailova and T. Chuy, “Catálogo de Los Terremotos Fuertes de la Región 16°/24°N y Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG  12 M. O. COTILLA-RODRÍGUEZ ET AL. -78°/-86°O, Desde el Siglo XVI Hasta 1988,” Informe científico-técnico, in Spanish, Institute de Geofísica y Astronomía, Academia de Ciencias de Cuba, 1993. [12] L. Álvarez, M. Rubio, T. Chuy and M. Cotilla, “Estudio de la Sismicidad de la Región del Caribe y Estimación Preliminar de la Peligrosidad Sísmica en Cuba,” Informe final del tema 310.01, in Spanish, Institute de Geofísica y Astro- nomía, Academia de Ciencias de Cuba, 1985. [13] K. Burke, J. Grippi and A. M. C. Sengor, “Neogene Structures in Jamaica and the Tectonic Style of the Northern Caribbean Boundary Zone,” The Journal of Ge- ology, Vol. 88, No. 4, 1980, pp. 375-386. [14] M. Cotilla, “Una Caracterización Sismotectónica de Cuba. Tesis en opción al grado de Doctor en Ciencias Geo- gráficas (especialidad geofísica),” in Spanish, Institute de Geofísica y Astronomía, Academia de Ciencias de Cuba, 1993. [15] C. DeMets, R. G. Gorden, D. F. Arges and S. Stein, “Current Plate Motions,” Geophysical Journal Interna- tional, Vol. 101, No. 2, 1990, pp. 425-438. [16] C. DeMets, P. E. Jansma, G. S. Mattioli, T. Dixon, P. Farina, R. Bilham, E. Calais and P. Mann, “GPS Geodetic Constraints on Caribbean-North American Plate motion,” Geophysical Research Letters, Vol. 27, No. 3, 2000, pp. 437-440. [17] J. Deng and L. R. Sykes, “Determination of Euler Pole for Contemporary Relative Motion of Caribbean and North American Plates Using Slip Vectors of Intraplate Earthquakes,” Tectonics, Vol. 14, 1995, pp. 39-53. [18] T. H. Dixon, F. Faina, C. DeMets, P. Mann and E. Calais, “Relative Motion between the Caribbean and North American Plates and Related Boundary Deformation from a Decade of GPS Observation,” Journal of Geo- physical Research, Vol. 103, No. B7, 1998, pp. 15157- 15182. [19] P. Mann, F. W. Taylor, R. Lawrence Edwards and K. U. Then-Lung, “Actively Evolving Microplate Formation by Oblique Collision and Sideways Motion along Strike-Slip Faults: An Example from the Northeastern Caribbean Plate Margin,” Tectonophysics, Vol. 246, No. 1-3, 1995, pp. 1-69. [20] L. R. Sykes, W. R. McCann and A. I. Kafka, “Motion of the Caribbean Plate during Last 7 Million Years: Implica- tions for Earlier Cenozoic Movements,” Journal of Geo- physical Research, Vol. 87, No. 13, 1982, pp. 10656- 10676. [21] Academias de Ciencias de Cuba y de Hungría, “Lev- antamiento Geológico de las Provincias Orientales, Escala 1:250,000,” in Spanish, Institute de Geología y Paleontología, 1981. [22] M. Cotilla, P. Bankwitz, H. J. Franzke, L. Álvarez, E. González, J. L. Díaz, G. Grünthal, J. Pilarski and F. Arteaga, “Mapa Sismotectónico de Cuba, Escala 1: 1,000,000,” Comunicaciones Científicas sobre Geofísicay Astronomía, in Spanish, Vol. 23, 1991, pp. 1-49. [23] J. Lewis and G. Draper, “Geology and Tectonic Evo- lution of the Northern Caribbean Region,” In: G. Deng and J. Case, Ed., The Caribbean Region: The Geology of North America, Geological Society of America, America, 1990, pp. 77-140. [24] E. Calais and B. Mercier de Lèpinay, “From Transtension to Transpression along the Southern Caribbean Plate Boundary off Cuba: Implications for the Recent Motion of the Caribbean Plate,” Tectonophysics, Vol. 186, No. 3-4, 1991, pp. 329-350. [25] P. Mann and K. Burke, “Neotectonics of the Caribbean,” Review of Geophysics and Space Physics, Vol. 22, No. 4, 1984, pp. 309-392. [26] J. F. Pacheco and L. R. Sykes, “Seismic Moment Catalog of Large Shallow Earthquakes, 1990 to 1989,” Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, Vol. 82, No. 3, 1992, pp. 1306-1349. [27] J. Prol, G. Ariaza and R. Otero, “Sobre la Confección de los Mapas de Profundidad del Basamento y Espesor de la Corteza Terrestre en el Territorio Cubano,” Informe cien- tífico-técnico de la Empresa Nacional de Geofísica, in Spanish, Ministerio de la Industria Básica de Cuba, 1993, p. 36. [28] V. I. Makarov, “Recent Tectonics of Eastern Cuba. Part 2. The Sierra Maestra-Baracoa Orogenic System. General conclusions,” Geotectonics, Vol. 21, No. 2, 1987, pp. 169-174. [29] E. C. Gónzalez, M. O. Cotilla, C. C. Cañete, J. L. Díaz, C. Carral and F. Arteaga, “Estudio Morfoestructural de Cuba,” Geografia Fisica e Dinamica Quaternaria, in Spanish, Vol. 26, No. 1, 2003, pp. 49-70. [30] M. Cotilla, E. González, H. J. Franzke, J. L. Díaz, J. Oro, F. Arteaga and L. Álvarez, “Mapa Neotectónico de Cuba, Escala 1:1,000,000,” Comunicaciones Científicas Sobre Geofísica y Astronomía, in Spanish, Vol. 22, 1991A, p. 37. [31] M. Cotilla and D. Córdoba, “Seismicity and Seismoactive Faults of Cuba,” Russian Geology and Geophysics, Vol. 48, No. 6, 2007, pp. 505-522. [32] Gaceta Médica de México, “Cronología Médica Mexic- ana. Curadores de heridas y boticarios,” in Spanish, 31 de Diciembre, 1945. [33] E. Bacardí, “Crónicas de Santiago de Cuba. Tomos 1-5,” Tipografía de Carbonell y Esteva, in Spanish, Barcelona- España, 1925. [34] J. de la Pezuela, “Diccionario Geográfico, Estadístico e Histórico de la Isla de Cuba,” Imprenta del Banco Industrialy Mercantil, in Spanish, Madrid, 1866. [35] J. de la Pezuela, “Diccionario Geográfico, Estadístico e Histórico de la Isla de Cuba,” Imprenta del Establecimiento de Mellado, in Spanish, Madrid, 1863. [36] J. Grases, “Terremotos Destructores del Caribe 1502- 1990,” UNESCO-RELACIS, in Spanish,Caracas, 1990. [37] D. Herrera, “Memoria Sobre Los Huracanes en la Isla de Cuba,” La Habana, in Spanish, 1847. [38] E. Monteulieu, “Notas y Apuntes Acerca de Terremotos Ocurridos en Cuba,” (Unpublished) Archivo del Instirute de Geofísica y Astronomía, in Spanish, Academia de Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG  M. O. COTILLA-RODRÍGUEZ ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. IJG 13 Ciencias de Cuba, 1968. [39] P. Salteraín y Legarra, “Ligera Reseña de los Temblores de Tierra Ocurridos en la Isla de Cuba,” Anales de la Academia de Ciencias Médicas, Físicas y Naturales de La Habana, in Spanish, Vol. 21, 1884, pp. 203-218. [40] A. Somohano, “A Catalogue of Earthquakes Felt at Cuba,” Thesis of Diploma of Imperial College, London, 1969. [41] J. Tomblin and G. R. Robson, “A Catalogue of Felt Earthquakes for Jamaica with References to Other Islands in the Greater Antilles, 1524-1971,” Mines Geology Di- vision Special Publication, Jamaica, 1977. [42] S. P. J. Lcitao, “La Ilustración Españolay Americana,” Selgas, in Spanish, Vol. XV, No. XXXII, 25 de Novi- embre 1871, p. 575. [43] Academia de Ciencias de Cuba, “Nuevo Atlas de Cuba,” in Spanish, Edited in Madrid, 1989. [44] E. Pichardo, “Geografía de la Isla de Cuba,” Establ- ecimiento Tipográfico de Don M. Soler, in Spanish, La Habana, 1854. [45] M. Cotilla and D. Córdoba, “Study of the Cuban Frac- tures,” Geotectonics, Vol. 44, No. 2, 2010A, pp. 176-202. [46] Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Sismológicas, CEN- AIS, “Informe del Terremoto del 25.05.1992 en Cabo Cruz,” in Spanish, Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Sismológicas, 1992. [47] T. Chuy, “Macrosísmica de Cuba y su Aplicación en Los Estudios de Peligrosidad y Microzonación Sísmica,” in Spanish, Fondos de la Fundación “García Siñériz”, España, 1999. [48] L. Morales y Pedroso, “El terremoto de Santiago de Cuba de 3 de Febrero de 1932,” Revista de la Sociedad Cubana de Ingenieros, in Spanish, Vol. 25, No. 2, 1933, pp. 123-166. [49] W. Sponheuer, “Methoden zur Herdtiefenstimmung der Makoseismik,” Freiberg Forschungs-hefte, C88, in Ger- man, Akademie Verlag, Berlin, 1960. [50] V. Karnik, “Seismicity of the European Area,” Reidel, Dodrecht, Vol. 1, 1969, pp. 64-82. [51] N. V. Shebalin, “Methods of Using Engineering-Seism- ology Data in Seismic Zoning”. In: S. F. Medvedev, Ed., Seismic zoning of the USSR, Akademik Nauk of USSR, 1968, pp. 101-121. |