Advances in Physical Education 2012. Vol.2, No.2, 68-72 Published Online May 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ape) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ape.2012.22012 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 68 Does Adherence Moderate the Effect of Physical or Mental Training on Episodic Memory in Older Women? Andrea Evers1, Verena Klusmann1, Ralf Schwarzer2,3, Isabella Heuser1 1Department of Psychiatry, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany 2Department of Psychology, Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany 3Warsaw School of Social Sciences and Humanities, Wroclaw, Poland Email: andrea.evers@psychologie.uni-heidelberg.de Received February 24th, 2012; revised March 27th, 2012; accepted April 8th, 2012 Objective: The aim was to investigate the overall amount of time spent on physical or mental activity training units (i.e., adherence) as a predictor of episodic memory performance in older healthy women. Methods: Women (N = 171, aged 70 - 93 years) took part in a 6-month randomized controlled trial (physical activity or computer training, 3 times weekly). Pre- and post-intervention episodic memory and adherence were assessed. Adherence covers the objectively measured frequency of training participation including travel time to and from course sites. Results: Within the physical exercise group, adherence (β = .19, p = .03) had positive effects on cognitive performance. In the computer group, an interaction be- tween adherence and pre-intervention episodic memory (β = −.17, p = .056) indicated improvement for low-ability women. Conclusions: Adhering to a stimulating mental or physical activity intervention is a prerequisite for healthy older women to maintain or slightly improve their episodic memory performance. Travel activity should be taken into account to cover an overall stimulation. Adherence to mental activity training indicates a moderating effect of mental activity training on episodic memory. Predominantly low-ability women improve their episodic memory performance. In contrast, adherence to physical activ- ity training is positively associated with cognitive performance, regardless of pre-intervention episodic memory performance. Keywords: Episodic Memory; Intervention; Adherence; Older Women; Exercise Introduction A decline in cognitive performance, especially with regard to episodic and working memory, is commonly observed with in- creasing age (Baltes, Staudinger, & Lindenberger, 1999; Singer, Verhaeghen, Ghisletta, Lindenberger, & Baltes, 2003). Obser- vational studies suggest that physically or mentally demanding activities counteract this decline (Hogan, 2005; Mackinnon, Christensen, Hofer, Korten, & Jorm, 2003), and experimentally controlled intervention studies find a positive effect of these activities on mental status in older people (Colcombe & Kramer, 2003; Heyn, Abreu, & Ottenbacher, 2004). Adherence to trainings is classically defined as the frequency of participation in a specific activity (Newson & Kemps, 2006) or the extent to which a person’s behavior corresponds to a recommendation, emphasizing the active role of the participant (Shields, Brawley, & Lindover, 2005). Adherence effects have to be studied for the following reasons: First, direct effects of adherence on outcomes often remain unclear, although inade- quate adherence is presumed to reduce the effectiveness of interventions (Brawley & Culos-Reed, 2000). Second, training responses among older adults vary. Individuals with lower baseline memory ability or at risk for impaired executive func- tion showed the greatest improvements in memory trainings, for example (Langbaum, Rebok, Bandeen-Roche, & Carlson, 2009). Third, measurement and assessment tools for adherence across various health behaviors do also diverge and there is no gold standard (Vitolins, Rand, Rapp, Ribisl, & Sevick, 2000). A strong relation between adherence and outcomes was found for continuous but not for dichotomous measures (DiMatteo, Giordani, Lepper, & Croghan, 2002). An adequate definition of adher- ence according to the studied behavior is mandatory to allow for unambiguous conclusions regarding the dose-response rela- tionship and of treatment consequences. According to Newson and Kemps (2006) the measure of adherence to activities should capture the overall level of stimulation. Aims of the Study In a recently reported randomized controlled trial (Klusmann et al., 2010) healthy women aged 70 years and older were allo- cated to either a 6-month standardized physical activity (i.e., exercise course), mental activity (i.e., a computer course), or a control group. Participants in both intervention groups similarly showed better cognitive performance change over 6 months than the controls. Here, we report on adherence to these com- puter and exercise courses and effects of adherence on episodic memory performance. We hypothesized that those women with lower baseline memory benefit most from adherence, regardless of the intervention group. We conceptualized adherence as “course attendance including travel time to and from the course sites” (Evers, Klusmann, Schwarzer, & Heuser, 2011b: p. 448). Methods Intervention and Participants We present adherence and its effect on cognitive performance  A. EVERS ET AL. from a recently reported randomized controlled trial (Klusmann et al., 2010), consisting of 259 healthy community-dwelling women aged 70 years and older. All participants were both unfamiliar with the computer and exercised less than one hour per week. One hundred and seventy-one women (age M = 73.6 years, SD = 4.2) were randomized to two behavioral intervene- tion programs: one physical training (n = 86), comprising aerobic, stretching, balance and muscle workouts, and one computer training (n = 85), comprising learning how to use common software and hardware. Both intervention programs consisted of standardized group trainings (7 groups à 12 participants), with the intensity of 90 minutes, the frequency of three times weekly and the duration of 6 months. On average, 73 course units were offered to each group (range 70 - 74). Group train- ings were conducted successively by a certified exercise or qualified computer trainer in different locations throughout Berlin which all were accessible by public transportation. It comes with the design of our study that adherence data exist solely for the intervention groups. The control group was in- structed to live their habitual life. This article focuses on the association between adherence and episodic memory perform- ance. Motivational and volitional aspects of adherence are dis- cussed elsewhere (Evers, Klusmann, Schwarzer, & Heuser, 2011a). Measures Baseline assessments and outcome measurements. Baseline assessments, study outcome measures, general cognitive status and demographic data were collected in a face-to-face situation. There were no missing data. Study outcome measures were assessed after termination of the 6-month intervention (Klus- mann et al., 2010). The following analyses focus on test scores of the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (FCSRT; Busch- ke, 1984), a valid episodic memory test to maximize learning while controlling attention and cognitive processing. The task requires learning and recall of 16 words presented as pictures using semantic categories as cues for encoding. The dependent variable is the sum score of three recall trials in a short delay condition, that is, separated by brief distractors (range of scores = 0 to 48). Adherence. The number of each 90-minute course unit at- tended (CA) was recorded by all trainers for each participant and intervention unit. The average individual travel time to and from course sites (TT; minutes), which was reported by the participants at follow-up, was added to each attended course unit. Adherence (A) was calculated by multiplying the number of course units attended (CA) with the duration of one interven- tion unit (i.e., 90 minutes) plus travel time to and from course locations (TT): ACA90 minutesTT (1) The result was converted into units of hours for reasons of convenience. Statistical Analyses Hierarchical regression analyses were conducted separately for both experimental groups. FCSRT follow-up scores were regressed on FCSRT baseline measurements and adherence (second step), controlling for age and educational level (first step). Third, interaction terms of baseline measurements and adherence were added for moderator testing. Variables were standardized to attain a common metric and prior to moderator testing. We used an SPSS macro provided by Hayes and Mat- thes (2009) to examine the interaction at three levels (mean ± 1 SD) of adherence. An additional output provided by the macro assists in the plotting of the conditional effect of adherence. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0. Results For regression analyses, data of all participants with fol- low-up assessment on the FCSRT were used regardless whether they discontinued the intervention at any point in time (inten- tion-to-treat). Age and educational level were included as cova- riates. Of 171 women who started the interventions, 161 women participated in the 6-month follow-up assessment, i.e., 80 women in the exercise condition and 81 women in the computer condi- tion. Data of the sample characteristics are summarized in Ta- ble 1. Experimental groups did not differ regarding demo- graphics and general cognitive status at baseline, and no sig- nificant group difference at baseline and follow-up in test scores of FCSRT was found; both intervention groups showed stable levels of performance. Adherence. Adherence was significantly lower in the exer- cise group compared to the computer group, t(159) = −3.24, p = .001. However, average travel time did not differ between these two groups, t(159) = 1.01, p = .316. Adherence did not significantly correlate with any of the baseline variables in none of the intervention groups. Regression Analyses Effects of adherence on post-test episodic memory perform- ance are presented separately for both intervention groups. Physical exercise group. The results of hierarchical regression analyses revealed a non-significant influence of the covariates age and educational level on FCSRT post-test scores. In the second step, baseline scores of the FCSRT were significant Table 1. Characteristics of the study population and descriptive statistics. Exercise group (n = 80) Computer group (n = 81) Age (yr) 73.5 ± 4.0 73.5 ± 4.2 Marital status Widowed (n) 26 (33%) 29 (36%) Married (n) 23 (29%) 13 (16%) Divorced (n) 22 (28%) 24 (30%) Other (n) 8 (10%) 9 (11%) Years of education 11.8 ± 2.5 12.1 ± 2.6 Mini-Mental State Examination28.8 ± .9 28.8 ± .9 Free word recall FCSRT short delay, pre-score 35.7 ± 3.9 35.1 ± 4.6 Free word recall FCSRT short delay, post-score 36.1 ± 4.3 34.7 ± 5.2 Travel time to courses, single way (min) 43.1 ± 16.3 40.4 ± 17.2 Course attendance (h) 75.7 ± 28.5 92.9 ± 20.6 Adherence (h) 146.5 ± 62.5 176.9 ± 53.3 Note: Unless otherwise noted, means ± SDs are reported. The range of scores on the Mini-Mental State Examination (Folstein & McHugh, 1975) is 0 to 30, with scores above 26 indicating no cognitive impairment. The range of scores on the free recall FCSRT short delay is 0 to 48 (sum score of three recall trials short delay separated by distracters). Adherence is defined as the number of course units attended including travel time, converted into units of hours. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 69  A. EVERS ET AL. predictors of FCSRT post-test scores (β = .64, p < .001). Adhe- rence emerged as a significant predictor (β = .19, p = .031, R2 = 43%). The inclusion of the interaction term of adherence and baseline scores of the FCSRT in the third step did not increase the variance explained. Computer group. The results of hierarchical regression analyses revealed a significant influence of age (β = −.35, p = .002) and a non-significant influence of educational level on FCSRT post-test scores. In the second step, baseline scores of the FCSRT emerged as significant predictors of FCSRT post-test scores (β = .58, p < .001). Adherence approached significance (β = .15, p = .089, R2 = 44%). In the third step, the inclusion of the interaction term of adherence and baseline scores of the FCSRT (β = −.17, p = .056) increased the variance explained (R2 = 46%), but the influence of adherence did not reach sig- nificance (β = .12, p = .178). Plotting the interaction at three selected levels of adherence (mean ± 1 SD) indicated that women with low test scores of FCSRT short delay at baseline and high adherence were pre- dicted to outperform people with the same low baseline scores but low adherence (Figure 1). Simple slope analyses revealed that the conditional effect of adherence was significant (p = .014) for women who performed 1 SD below group mean (<30.5) at pre-testing. In other words, spending about 3 hours three times a week for six months (i.e., 230 hours/73 units) yielded an optimal benefit for this group. Table 2 contains the findings of the regression analyses.1 Discussion The objective of the present article was to investigate the in- fluence between adherence in two different intervention pro- grams and episodic memory performance. In our study, adherence represented the overall amount of time spent on course partici- pation. It has been reported that the relationship between adherence and outcome measures is complex and that variability in re- sponsiveness to training is considerable (DiMatteo et al., 2002). Although the intervention groups differed significantly in adhe- rence, no significant difference in pre- and post-test scores of episodic memory emerged. On average participants maintained their level of performance and we found baseline memory per- formance to have a strong influence on the outcome of memory performance. In the exercise group, adherence emerged as a weak predictor of episodic memory performance. A moderating effect of adhe- rence on the association between baseline and post-test scores was not found. Thus, we conclude that effects on episodic memory seem to be due to 90 minutes of combined exercise training as proposed in Colcombe and Kramer (Colcombe & Kramer, 2003). For the mental activity group, adherence did not predict epi- sodic memory performance; however, a moderating effect of adherence indicated beneficial effects of adherence for low- baseline women only. We reason that the negative influence of age might be mitigated if older women spent time in a chal- lenging mental activity. Travel time seems to boost intervention effects by an addi- tional physical and mental stimulation. All but three partici- pants were public transit commuters or walked to course loca- tions. Spending about 80 minutes on average for travelling (round trip) on each 90-minute course unit appears to have contributed to an additional, albeit unspecific, activity (Wener & Evans, 2007). We found the computer course to have im- proved slightly in the 6-minute walking test (Klusmann et al., 2010). Hence, one could carefully assume that the positive effect of adherence (including travel activity) on cognitive per- formance is due to an increased fitness level by an additional “transportation activity” (Hamer & Chida, 2008). Participants in the computer course similarly might have been mentally stimulated while being “en-route”. They likely have been reflecting upon or occupying themselves with their course work, reworking previous course units and preparing themselves for current units. Thereby the cognitively stimulat- ing effect might have been continued beyond the actual inter- vention. These mental activities seem to be less relevant in a physical activity course which relies much less on teaching contents of previous lessons. To conclude, travel time may be an additional physical and/or mental stimulation, depending on the content of courses attended. By amending adherence with the information of the time needed to participate, an overall level of stimulation is covered (Newson & Kemps, 2006). Furthermore, the frequency of par- ticipation is often based on self-reported data (e.g., Glazebrook & Brawley, 2011); the strength of our approach is that the num- ber of course units attended was measured objectively. Limitations of the Study The reported adherence effects were derived by relying on the outcome of one episodic memory test. Furthermore, a dose- response effect of activity on cognition could not be calculated, because participants were not randomized to different groups of intensity, and adherence in our study turned out to be consistently high. In future studies, pedometers could be used to measure additional physical activity (Wener & Evans, 2007). Participants in 1Repeating the analyses with adherence excluding travel activity, adherence emerged as a significant predictor for the activity group only (activity group: β = .17, p = .045; computer group: β = .05, p = .568). The inclusion of the interaction term of adherence and baseline scores of the FCSRT in the third step approached significance (activity group: β = .16, p = .080; computer group: β = −.16, p = .090). The positive interaction in the activity group indicated improvement for high-ability women only, i.e., women who per- formed 1 SD above group mean at pre-measurements of the FCSRT. Figure 1. Computer group (n = 81): Prediction of post-test scores on FCSRT short delay at three different values of adherence (mean ± 1 SD). Spending a lot of time (i.e., on average 230 h in 6 months) has a posi- tive effect for participants performing 1.5 SD below mean at baseline memory performance. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 70  A. EVERS ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 71 Table 2. Regression coefficients for variables predicting post-test episodic memory performance (FCSRT short delay) for both intervention groups. Exercise group Computer group Variable β SEB p ∆R2 2 corr R β SEB p ∆R2 2 corr R Step 1 Age −.15 .11 .179 −.35 .11 .002 Years of education .16 .11 .158 .03 .04 .11 .692 .10 Step 2 Age −.04 .09 .627 −.21 .09 .017 Years of education .03 .09 .705 .03 .09 .771 Baseline .64 .09 .000 .58 .09 .000 Adherence .19 .09 .031 .40 .43 .15 .09 .089 .35 .44 Step 3 Age −.04 .09 .691 −.20 .09 .023 Years of education .04 .09 .652 .05 .09 .552 Baseline .66 .09 .000 .55 .09 .000 Adherence .16 .09 .075 .12 .09 .178 Baseline x Adherence .11 .10 .210 .01 .43 −.17 .07 .056 .03 .46 Note. Baseline refers to pre-test score of free word recall FCSRT short delay; covariates: age, years of education. our study were healthy and well-educated, resembling a sample of successfully aging women, and ceiling effects are likely to have played a role. Conclusion Adhering to a challenging physical or mental training inter- vention enables healthy older women to maintain or slightly improve their episodic memory performance. Adherence effects depend on participants’ pre-intervention cognitive status: Ad- hering to a physical activity intervention is beneficial for high- and low-ability women; predominantly low-ability women improve their episodic memory by spending a large amount of time on a stimulating mental activity intervention. In doing so, adherence covers not only the frequency of participation but also travel activity as an additional physical and mental stimu- lation. Acknowledgements This research was funded by non-profit sponsors: German Research Foundation: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), Doctoral Program “Neuropsychiatry and Neuropsychology of Aging” (grant 429); Gertrud and Hugo Adler Foundation. The study was developed and designed under the leadership of Pro- fessor Isabella Heuser who was the recipient of the grants. REFERENCES Baltes, P. B., Staudinger, U. M., & Lindenberger, U. (1999). Lifespan psychology: Theory and application to intellectual functioning. An- nual Review of Psychology, 50, 471-507. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.471 Brawley, L. R., & Culos-Reed, S. N. (2000). Studying adherence to therapeutic regimens: Overview, theories, recommendations. Con- trolled Clinical Trials, 21, 156S-163. doi:10.1016/S0197-2456(00)00073-8 Buschke, H. (1984). Cued recall in amnesia. Journal of Clinical Neu- ropsychology, 6, 433-440. doi:10.1080/01688638408401233 Colcombe, S., & Kramer, A. F. (2003). Fitness effects on the cognitive function of older adults: A meta-analytic study. Psychological Science, 14, 125-130. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.t01-1-01430 DiMatteo, M. R., Giordani, P. J., Lepper, H. S., & Croghan, T. W. (2002). Patient adherence and medical treatment outcomes: A meta-analysis. Medical Care, 40, 794-811. doi:10.1097/01.MLR.0000024612.61915.2D Evers, A., Klusmann, V., Schwarzer, R., & Heuser, I. (2011a). Adher- ence to physical and mental activity interventions: Coping plans as a mediator and prior adherence as a moderator. British Journal of Health Psychology. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8287.2011.02049.x Evers, A., Klusmann, V., Schwarzer, R., & Heuser, I. (2011b). Improv- ing cognition by adherence to physical or mental exercise: A moder- ated mediation analysis. Aging & Mental Health, 15, 446-455. doi:10.1080/13607863.2010.543657 Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., & McHugh, P. R. (1975). Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12, 189-198. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 Glazebrook, K. E., & Brawley, L. R. (2011). Thinking about maintain- ing exercise therapy: Does being positive or negative make a differ- ence? Journal of Health Psychology, 16, 905-916. doi:10.1177/1359105310396391 Hamer, M., & Chida, Y. (2008). Active commuting and cardiovascular risk: A meta-analytic review. Preventive Medicine: An International Journal Devoted to Practi c e and Theory, 46, 9-13. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.03.006 Hayes, A. F., & Matthes, J. (2009). Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 924-936. doi:10.3758/BRM.41.3.924 Heyn, P., Abreu, B. C., & Ottenbacher, K. J. (2004). The effects of exercise training on elderly persons with cognitive impairment and dementia: A meta-analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Re- habilitation, 85, 1694-1704. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2004.03.019 Hogan, M. (2005). Physical and cognitive activity and exercise for older adults: A review. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 60, 95-126. doi:10.2190/PTG9-XDVM-YETA-MKXA Klusmann, V., Evers, A., Schwarzer, R., Schlattmann, P., Reischies, F. M., Heuser, I., & Dimeo, F. C. (2010). Complex mental and physical activity in older women and cognitive performance: A 6-month ran- domized controlled trial. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Bio- logical Sciences and Medical Sciences, 65, 680-688. doi:10.1093/gerona/glq053 Langbaum, J. B. S., Rebok, G. W., Bandeen-Roche, K., & Carlson, M. C. (2009). Predicting memory training response patterns: Results from ACTIVE. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological  A. EVERS ET AL. Sciences and Social Sc iences, 64B, 14-23. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbn026 Mackinnon, A., Christensen, H., Hofer, S. M., Korten, A. E., & Jorm, A. E. (2003). Use it and still lose it? The association between activity and cognitive performance established using latent growth tech- niques in a community sample. Aging, Neuropsychology & Cogni- tion, 10, 215-229. doi:10.1076/anec.10.3.215.16451 Newson, R. S., & Kemps, E. B. (2006). The influence of physical and cognitive activities on simple and complex cognitive tasks in older adults. Experimental Aging Research, 32, 341-362. doi:10.1080/03610730600699134 Shields, C. A., Brawley, L. R., & Lindover, T. I. (2005). Where percep- tion and reality differ: Dropping out is not the same as failure. Jour- nal of Behavioral M e dicine, 28, 481-491. doi:10.1007/s10865-005-9012-9 Singer, T., Verhaeghen, P., Ghisletta, P., Lindenberger, U., & Baltes, P. B. (2003). The fate of cognition in very old age: Six-year longitudi- nal findings in the Berlin Aging Study (BASE). Psychology and Ag- ing, 18, 318-331. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.318 Vitolins, M. Z., Rand, C. S., Rapp, S. R., Ribisl, P. M., & Sevick, M. A. (2000). Measuring adherence to behavioral and medical interventions. Controlled Clinical Trials, 21, 188S-194. doi:10.1016/S0197-2456(00)00077-5 Wener, R. E., & Evans, G. W. (2007). A morning stroll: Levels of physical activity in car and mass transit commuting. Environment and Behavior, 39, 62-74. doi:10.1177/0013916506295571 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 72

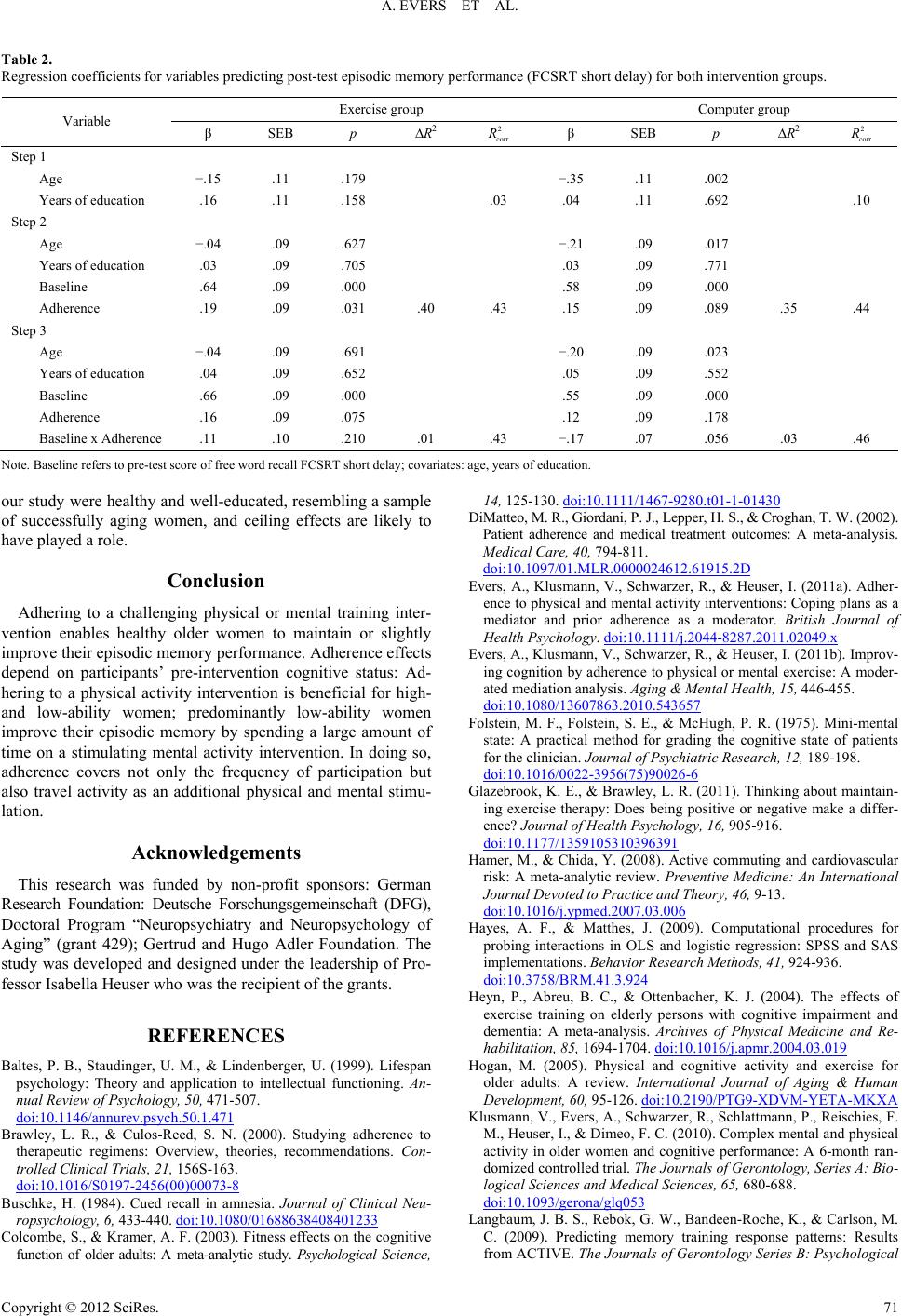

|