Open Journal of Pediatrics

Vol.3 No.3(2013), Article ID:36368,4 pages DOI:10.4236/ojped.2013.33047

Rothmund-thomson syndrome and cutan T-cell lymphoma in childhood

![]()

1Department of Pediatrics, Szeged University School of Medicine, Szeged, Hungary

2Department of Pathology, Szeged University School of Medicine, Szeged, Hungary

Email: bartyik.katalin@med.u-szeged.hu

Copyright © 2013 Katalin Bartyik et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 22 April 2013; revised 25 May 2013; accepted 2 June 2013

Keywords: Rothmond Thomson Syndrome; Genetic Disorder; Cutan T-Cell Lymphoma

ABSTRACT

We report a 3-year-old girl suffering from RothmundThomson Syndrome (RTS). The patient at birth had multiplex anomalies: poikilodermatous rash, sceletal abnormalities: palatoschisis, micrognathi, aplasia radii, hypoplastic right and left thenar and thumbs, pesequinus on both site, ectopy renis. The patient in the later ages was detected dental malformation, facial dysmorfism. At the age 3, she had lasion in her muscle. After biopsy, histological examination showed cutan T-cell lymphoma. The patient is the first case who had cutan T-cell lymphoma associated with RTS in this young age.

1. INTRODUCTION

The RTS was described firstly in 1868 by Rothmund. Up to nowadays approximately 400 cases have been reported in the literature. Cells from patients with RTS demonstrate genomic instability, mutations in RECQL4 gene [1-3].

RTS patients are particularly prone to developing osteosarcoma as well as nonmelanoma skin cancers [4-15]. RTS has been grouped with other genetic cancer predisposition disorders that fall into the class of DNA repair or chromosomal instability disorders. Patients with other disorders have well-known increased sensitivity to DNAdamaging agents including ionizing radiation and ultraviolet radiation [16]. Usually the disease tends to progress during the first year of life, but becomes static so that patients may have a normal lifespan with a good quality of life.

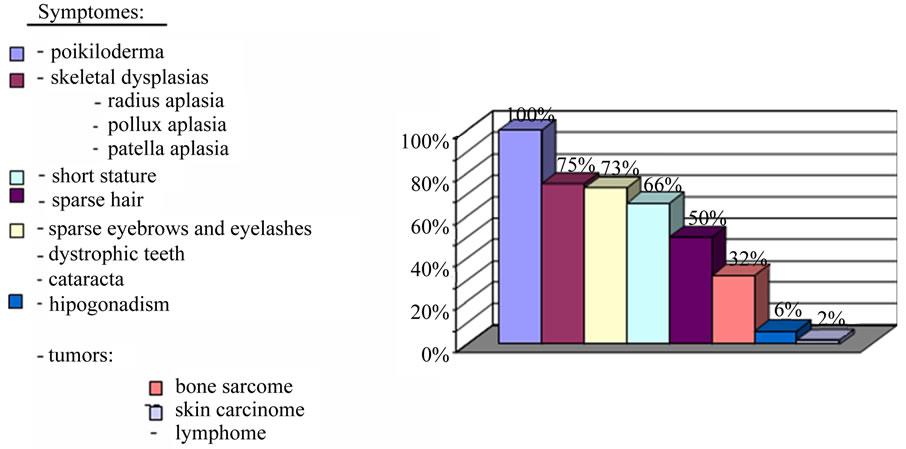

The mortality from neoplastic disease during the second or third decade is very significantly increased [17- 23]. Patients generally present: skin rash, small statureand skeletal dysplasias.

Cutaneous symptoms: photosensitivity, poikiloderma, hyperkeratosis, alopecia.

Other abnormalities: dystrophic teeth, nails, juvenile cataract, short stature, hypogonadysm, congenital bone defects, soft tissue contractures, mental retardation. More than 90% of patients develop the initial skin manifestations during the first year of life, usually from age 3 - 6 months. The acute phase begins in early infancy as red patches or edematous plaques, sometimes with blistering. The cheeks are usually first involved, later spread to other areas of the face, the extremities, and the buttocks. Over months to years, the rash enters a chronic stage characterized by poikiloderma (atrophy, telangiectasias, and pigmentary changes). Photosensitivity is a feature in more than 30% of cases. The characteristic skin findings are the most consistent feature of the syndrome. Irregular erythema and edema of the skin are replaced by reticulated red-brown patches associated with punctate atrophy and telangiectasias (poikiloderma). These characteristic skin changes are typically seen on the face, extensor extremities, and buttocks with sparing of the chest, abdomen, and back.

Acral hyperkeratotic lesions on the elbows, knees, hands, and feet can be seen at puberty. Palmar keratoderma has been reported [24]. Patients may have sparse hair, premature canities, and dystrophic or atrophic nails.

Dental abnormalities include malformation: microdontia, failure of eruption.

Juvenile cataracts have been reported in as many as 40% - 50% of patients aged 4 - 7 years. Patients usually have short stature, which ranges from dwarfism to a small build.

About one half of patients have skeletal abnormalities, most frequently a characteristic facies with frontal bossing, saddle nose, and micrognathia. Small hands and feet disproportionate to the patient’s body size are observed in 20% of patients. Approximately 10% of patients have absent or malformed radii, and 5% of patients have absent or partially formed thumbs (Figure 1).

2. CASE REPORT

Our patient was born in 40 gestation weeks, with 2430 gr. At birth had multiplex anomalies: poikilodermatous rash, palatoschisis, skeletal abnormalities (aplasia radii, hypoplastic right and left thenar and thumbs, pes equinus on both side), ectopy renis. Chromosome examination showed: 46(XX), normal kariotype. Further dental malformations, growth retardation, cranial dysostosis with saddle nose and facial dysmorfism, sparse scalp hair, eyebrows and eyelashes, teleangiectasia, dystrophic nails and photosensitivity, mild mental retardation (Figure 2).

At the age of 3 years old, she had lesions in her muscle (nose and shanks) (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 1. Frequency of symptomes.

Figure 2. Skin poikiloderma.

Figure 3. Nasal destruction.

Figure 4. Shank destruction.

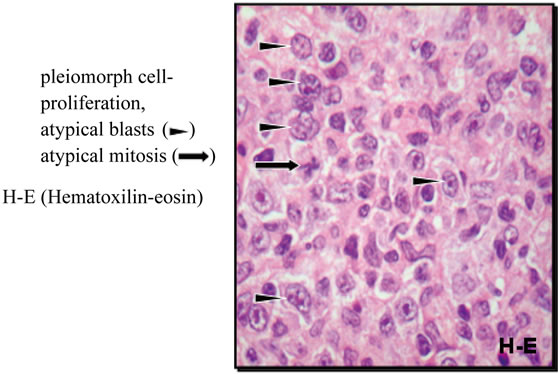

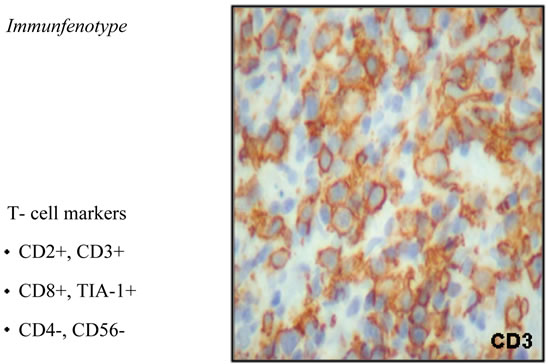

The patient was treated as the pyoderma gangrenosum by dermatologist. Inspite of adminestered antibiotics in low and mild dosis and steroid was not improvement in a muscle lesion. Progression of the symptomes biopsy was performed. Histological examination showed cutan T-cell lymphoma (Figures 5 and 6).

At the first admission she had negative ultrasaund and chest X-Ray results. Peripheral blood smears showed mild anaemia (Ht: 0.29, Hb: 92 g/l). Liver and kidney function was normal.

Flow cytometry of bone marrow was normal. Bacterial culture result from secretion of leison was: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Proteus vulgaris, Streptococcus pyogenes. Antibiotic therapy was given (ceftriaxone, aminoglycosid, clindamycin).

We started with NHL BFM SR (low risk) protokol (induction: prednisolon (60 mg/m2/day) Vincristin 2 mg/m2/ week, Daunorubicin 20 mg/m2/week, Asparaginase 10,000 U/m2 2×/week).

At the beginning of treatment, Central Vein Catheter (CVC) implantation was revealed into jugular vein. The skin necrose was improved 2 weeks later. On the 3rd week of the treatment in relatively good condition she suddenly died at home. Dissection showed thrombosis in central vein catheter and sinus sagittalis superior vein, inspite of the catheter heparinisation. It was an unexpected event.

3. DISCUSSION

We report a new case of cutan T-cell lymphoma assotiation with Rothmund-Tomson Syndrome. Our patient, who had RTS and childhood cutan T-cell lymphoma in young age, had a typical RTS, and she was the first case.

Cutan T-cell lymphoma is an extranodal, indolent nonHodgkin lymphoma of T-cell origin that primarily develops in the skin, but can involve the lymph nodes, blood, and visceral organs. This is the adult type of lymphoma, but very rare in childhood.

The RTS association with malignancy is well known.

Figure 5. Histology.

Figure 6. T-cell markers histology.

Many osteosarcomas are described in the literature association with RTS. During the second or third decade malignancy is very significantly increased, but very rare in very young age.

Sudden death was unexpected. Maybe the cause of death outputs some thrombotic agents from damage tissue, asparaginase and RTS.

Early diagnosis is very important for the newborn baby with multiplex anomalies.

Cutaneous and extracutaneous features of cancer-predisposing syndrome should result in the early diagnosis of an underlying cancer in children.

Careful prevention and follow-up are very important, so that we can take early diagnosis of cancer. Unfortunately our patient died from unexpected event, therefore, we don’t know if the therapy is successful or not.

![]()

![]()

REFERENCES

- Simon, T., Skohlhase, J., Wilhelm, C., Kochanek, M., De Carolis, B. and Berthold, F. (2010) Multiple malignant diseases in a patient with Rothmund-Thomson syndrome with RECQL4 mutations: Case report and literature review. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 152A, 1575-1579.

- Maire, G., Yoshimoto, M., Chilton-MacNeill, S., Thorner, P.S., Zielenska, M. and Squire, J.A. (2009) Recurrent RECQL4 imbalance and increased gene expression levels are associated with structural chromosomal instability in sporadic osteosarcoma. Neoplasia, 11, 260-268.

- Holman, J.D. and Dyer, J.A. (2007) Genodermatoses with malignant potential. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 19, 446-454. doi:10.1097/MOP.0b013e3282495939

- Hicks, M.J., Roth, J.R., Kozinetz, C.A. and Wang, L.L. (2007) Clinicopathologic features of osteosarcoma in patients with Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 25, 370-375. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.08.4558

- Gelaw, B., Ali, S. and Becker, J. (2004) Rothmund-Thomson syndrome, Klippel-Feil syndrome, and osteosarcoma. Journal of Skeletal Radiology, 33, 613-615.

- Anbari, K.K., Ierardi-Curto, L.A., Silber, J.S., Asada, N., Spinner, N., Zackai, E.H., Belasco, J., Morrissette, J.D. and Dormans, J.P. (2000) Two primary osteosarcomas in a patient with Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 213-223. doi:10.1097/00003086-200009000-00032

- Spurney, C., Gorlick, R., Meyers, P.A., Healey, J.H. and Huvos, A.G. (1998) Multicentric osteosarcoma, RothmundThomson syndrome, and secondary nasopharyngeal nonHodgkin’s lymphoma: A case report and review of the literature. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, 20, 494-497. doi:10.1097/00043426-199809000-00018

- el-Khoury, J.M., Haddad, S.N. and Atallah, N.G. (1997) Osteosarcomatosis with Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. British Journal of Radiology, 70, 215-218.

- Padhy, D., Madhuri, V., Pulimood, S.A., Danda, S., Walter, N.M. and Wang, L.L. (2010) Metatarsal osteosarcoma in Rothmund-Thomson syndrome: A case report. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, 92, 726-730. doi:10.2106/JBJS.I.00478

- Green, J.S. and Rickett, A.B. (1998) Rothmund-Thomson syndrome complicated by osteosarcoma. Pediatric Radiology, 28, 48-50. doi:10.1007/s002470050290

- Macura, K.J., Burke, G. and Robinson, V.J. (1998) Osteogenic sarcoma associated with the Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Clinical Nuclear Medicine, 23, 116-118. doi:10.1097/00003072-199802000-00017

- Howell, S.M. and Bray, D.W. (2008) Amelanotic melanoma in a patient with Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Archives of Dermatology, 144, 416-417. doi:10.1001/archderm.144.3.416

- Stinco, G., Governatori, G., Mattighello, P. and Patrone, P. (2008) Multiple cutaneous neoplasms in a patient with Rothmund-Thomson syndrome: Case report and published work review. The Journal of Dermatology, 35, 154- 161. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2008.00436.x

- Piquero-Casals, J., Okubo, A.Y. and Nico, M.M. (2002) Rothmund-Thomson syndrome in three siblings and development of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Pediatric Dermatology, 19, 312-316. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.2002.00089.x

- Capell, B.C., Tlougan, B.E. and Orlow, S.J.J. (2009) From the rarest to the most common: Insights from progeroid syndromes into skin cancer and aging. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 129, 2340-2350.

- Dahele, M.R., Benton, E.C., Hennessy, A., MacDougall, R.H., Price, A., Mitchell, R. and Watson, J. (2004) A patient with Rothmund-Thomson syndrome and tongue cancer—Experience of radiation toxicity. Clinical Oncology, 16, 371-372. doi:10.1016/j.clon.2004.05.001

- Pencovich, N., Margalit, N. and Constantini, S. (2012) Atypical meningioma as a solitary malignancy in a patient with Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Surgical Neurology International, 3, 148. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.104742

- Castori, M., Morrone, A., Kanitakis, J. and Grammatico, P. (2012) Genetic skin diseases predisposing to basal cell carcinoma. European Journal of Dermatology, 22, 299- 309.

- Carlson, A.M., Lindor, N.M. and Litzow, M.R. (2011) Therapy-related myelodysplasia in a patient with RothmundThomson syndrome. European Journal of Haematology, 86, 536-540. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0609.2011.01609.x

- Pianigiani, E., De Aloe, G., Andreassi, A., Rubegni, P. and Fimiani, M. (2001) Rothmund-Thomson syndrome (Thomson-type) and myelodysplasia. Pediatric Dermatology, 18, 422-425. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.2001.01971.x

- Broom, M.A., Wang, L.L., Otta, S.K., Knutsen, A.P., Siegfried, E., Batanian, J.R., Kelly, M.E. and Shah, M. (2006) Successful umbilical cord blood stem cell transplantation in a patient with Rothmund-Thomson syndrome and combined immunodeficiency. Clinical Genetics, 69, 337-343. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00592.x

- Marín-Bertolín, S., Amorrortu-Velayos, J. and Aliaga Boniche, A. (1998) Squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue in a patient with Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. British Journal of Plastic Surgery, 51, 646-648. doi:10.1054/bjps.1998.0050

- Ilhan, I., Arikan, U. and Büyükpamukçu, M. (1995) Rothmund-Thomson syndrome and malignant fibrous histiocytoma: A case report. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/ Oncology, 12, 103-105. doi:10.3109/08880019509029540

- Popadić, S., Nikolić, M., Gajić-Veljić, M. and BonaciNikolić, B. (2006) Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. The first case with plantar keratoderma and the second with coeliac disease. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat, 15, 90-93.

ABBREVIATIONS

Rothmund-Thomson Syndrome (RTS)

Central Vein Catheter (CVC)