Sociology Mind 2012. Vol.2, No.2, 158-168 Published Online April 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/sm) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/sm.2012.22021 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 158 Are Asian Americans Disadvantaged by Residing More in the West? Migration, Region, and Earnings among Asian American Men Isao Takei1, Arthur Sakamoto2, Daniel A. Powers2 1Department of International Relations, Nihon University, Mishima, Japan 2Department of Sociology, University of Texas, Austin, USA Email: takei.isao@nihon-u.ac.jp Received January 23rd, 2012; revised February 26th, 2012; accepted March 28th, 2012 In studying labor market inequality of Asian Americans, the role of region and migration remain key fac- tors that have not been much taken into account in the prior research. Using the 2003 National Survey of College Graduates (NSCG), this study examines whether native-born and 1.5-generation Asian Ameri- cans are more likely than whites to reside in the West. We also investigate whether native-born and 1.5-generation Asian Americans have higher earnings than whites when broken down by West versus non-West. In addition to an OLS regression model, a switching regression model is used in order to ac- count the possibility of sample selectivity between wages and region among men who are observed to re- side in the West and in the non-West. This study can therefore ask, net of demographic and socioeco- nomic factors and selectivity, if there is no differential in earnings between Asian Americans and whites in the West, as well as in the non-West. The results of this study indicate that Asian Americans are more likely than whites to currently reside in the West, regardless of age category and nativity. This study also finds that Asian American men do not face a substantial disadvantage in the US labor market, net of demographic and class factors. Finally, switching regression models demonstrate that both younger na- tive-born and younger 1.5-generation Asian Americans in the West and 1.5-generation Asian Americans in the non-West have significantly higher average earnings than whites, after further controlling for selec- tivity. This indicates that the estimated earnings differentials for younger Asian Americans and whites are obscured when using OLS, which does not account for selectivity. In regard to selectivity, there is a posi- tive selection into living in the West, while the selection is negative living into the non-West. Keywords: Asian Americans; Wages; Region; Switching Regression; 2003 National Survey of College Graduates (NSCG) Introduction The Continui ng D ebate on the Disadvantage of Asian Americans as a Minority in the Labor Market A number of studies show that Asian Americans faced direct and overt racial discrimination in the labor market before World War II (e.g., Bonacich, 1972, 1973; Bonacich & Modell, 1980; Boswell, 1986; Chin, 2005; Ichihashi, 1932; Ichioka, 1988; Jiobu, 1988; Kitano, 1976; Kitano & Daniels, 2001; Le- vine & Montero, 1973; Lieberson, 1980; Lyman, 1974; Makabe, 1981; McLemore, 1994; Okihiro, 1994). Some research argues that labor market discrimination against this racial group persists during the period after World War II, and that their socioeconomic attainments are greatly exaggerated. The seminal citation in this literature is Hirschman and Wong (1984: p. 584) who conclude that “Asian Americans approach socioeconomic parity with whites because of their overachievement in educational attainment”. Hirschman and Wong (1984) note that the average earnings and occupational attainments of Asian Americans did not differ very much from those of whites at least in the data that they studied. However, because Asian Americans tend to have higher educational at- tainments, the labor market can be construed to be discriminat- ing against them in that they must make a higher investment in human capital in order to obtain the same socioeconomic re- wards as whites. The over-education view is supported by other studies (e.g., Barringer, Takeuchi, & Xenos, 1990; Chin et al., 1996; Feagin & Feagin, 1993; Fong, 1998; Kao, 1995; Marti- nelli & Nagasawa, 1987; McCall, 2001; Min, 1995; Takaki, 1998; Waters & Eschbach, 1995; Wong, 1982; Wong et al., 1998; Zhou & Kamo, 1994), collectively suggesting continuing labor market discrimination against Asian Americans in the post-World War II era, given this group’s high level of education. Several more recent studies also support the over-education view. For example, using data from the 1970, 1980, and 1990 PUMS, Hirschman and Snipp (2001) find that Asian American men (i.e., Chinese and Japanese) are equal to or above white men in their occupational positions measured in terms of the Duncan Socioeconomic Index, but that Filipino men hold slightly lower jobs than whites. Hirschman and Snipp (2001) note that the reason for the higher occupational attainment of Asian American men is simply their educational level—if the Asian American men had the same education as white men, there would be only modest racial occupational differences. Furthermore, the authors find that Chinese and Filipino men earn less than whites, although this gap is somewhat less than blacks, American Indians, and Hispanics. Hirschman and Snipp (2001) conclude that these results—the persistence of race and ethnic differentials in late twentieth-century America—chal- lenge conventional theories about the declining significance of race in the US stratification system (also see Snipp & Hirsch- man, 2004).  I. TAKEI ET AL. However, empirical findings about Asian American labor market disadvantage seem to be affected by types of data em- ployed for the analysis. For example, much of the previous research supporting the over-education view (e.g., Hirschman & Snipp, 2001; Snipp & Hirschman, 2004) includes the first- generation (i.e., foreign-born) Asian Americans in the analysis, who may face reduced labor market opportunities for various reasons other than discrimination in the labor market. For ex- ample, prior research argues that higher education attained abroad may be undervalued by American employers who are generally unfamiliar with foreign universities (Bratsberg & Ragan, 2002; Zeng & Xie, 2004). In addition, immigrants may have limited English-language skills, and be less familiar with American labor market practices and institutions (Espenshade & Fu, 1997; Sakamoto, Goyette, & Kim, 2009). The inequality deriving from immigrant-status related resources, which gener- ally affect one’s labor market competitiveness, should not be confused with racial discrimination. Indeed, most studies of native-born Asian Americans using recent data (i.e., after 1990) do not find that they face any sub- stantial and systematic disadvantage in terms of wages and earnings in the contemporary labor market, when controlling for highest educational level completed and other basic demo- graphic variables (Chiswick, 1983; Iceland, 1999; Kim & Mar, 2007; Ko & Clogg, 1989; Sakamoto & Furuichi, 1997, 2002; Sakamoto & Kim, 2003; Sakamoto, Liu, & Tzeng, 1998; Sa- kamoto, Wu, & Tzeng, 2000; Sakamoto, Takei, & Woo, 2011; Xie & Goyette, 2004; Zeng & Xie, 2004). This general conclu- sion seems to apply not only to Asian Americans as a racial category but also to particular ethnic groups such as Asian In- dians (Woo, Sakamoto, & Takei, 2012) as well as Cambodians, Hmong, Laotians, and Vietnamese (Sakamoto & Woo, 2007). Furthermore, prior research (e.g., Barringer, Gardner, & Levin, 1993; Sakamoto & Xie, 2006; Xie & Goyette, 2004) demonstrates that Asian Americans as a whole (especially among the native-born) tend to have higher mean values on most indicators of socioeconomic status (e.g., education, in- comes, hourly wages, and employment in professional and technical occupations), and that they are not disadvantaged in labor market stratification processes (Fang, 1996; Farley & Alba, 2002; Iceland, 1999; Ko & Clogg, 1989; Montero, 1980; Sakamoto & Xie, 2006; Xie & Goyette, 2004; Zeng & Xie, 2004). This general pattern in part derives from having parents who tend to have higher levels of educational attainment them- selves (Sakamoto & Xie, 2006). Such research collectively suggests that net of education and basic demographic charac- teristics, there is no significant differential in the socioeco- nomic attainments between Asian Americans and non-Hispanic whites. Namely, it is argued that the racial differentials are mostly explained by and depend upon class characteristics and market resources. The Role of Region in Asian American Labor Market Outcomes The literature review introduced above shows that the extent to which Asian Americans face discrimination in the labor market is a subject of considerable debate. In examining this debate, region of residence and migration play important roles (Mar, 1999). Compared to non-Hispanic whites, Asian Ameri- cans tend to have a different regional distribution and their tra- ditional residential states (i.e., California, Washington, Hawaii, New York and New Jersey) tend to have a high cost of living. Cabezas and Kawaguchi (1988) argue that the seeming parity between Asian Americans and non-Hispanic whites is merely an artifact of regional location. Regional distribution of Asian Americans is most characterized by their concentration in cer- tain states and regions, such as Hawaii, California, and the West Coast, primarily due to the fact that these were the places of residence after arrival from abroad of the earlier immigrants (Allen & Turner, 1988; Barringer, Gardner, & Levin, 1993; Hurh & Kim, 1989; Lyman, 1977). Since Asian Americans are primarily concentrated in the high wage/high cost of living western United States (Hurh & Kim, 1989; Takaki, 1998; US Commission on Civil Rights, 1988), especially in cities rather than rural areas (Takaki, 1998), it is argued that the unadjusted average US earnings comparisons between Asian Americans and non-Hispanic whites are inappropriate comparisons of eco- nomic progress (Mar, 1999). Indeed, prior research shows that Asian Americans are ad- versely affected by their place of residence. Using data from the 1970, 1980, and 1990 PUMS, Snipp and Hirschman (2004: p. 110) note that, “[i]nterestingly, unlike other minorities, Asian men residing in areas with large populations of co-ethnics, namely California and Hawaii, have occupational statuses which are slightly lower than Asian men living elsewhere. In the absence of this liability, the occupational statuses of Japa- nese and Chinese men in California and Hawaii would be an average of 1 to 6 points higher.” Therefore, Snipp and Hirsch- man (2004: p. 115) conclude that “at least Asian American men are disadvantaged by their geographic concentrations.” Using 1990 PUMS, Mar (1999) examines the role of location in the earnings discrimination of three groups of Asian Americans: Japanese, Chinese, and Filipinos. Mar’s (1999) findings from the regional comparisons of earnings differentials by race sug- gest that Asian American (i.e., Chinese and Japanese) men en- counter less labor market discrimination in Hawaii than in California. In particular, Mar (1999) finds that earnings for Filipino men are significantly lower than non-Hispanic whites in California once differences in human capital are taken into account. Fuji and Mak (1985) find that Filipino men have lower returns to education in Hawaii than the rest of the United States. Furthermore, when controlling for field of study and college type among college graduates, Kim and Sakamoto (2008) find that also controlling for region of residence results in a net dis- advantage of about 8 percent for native born Asian American men. Kim and Sakamoto (2008) note that, to the extent that region of residence should be considered to be a necessary con- trol variable, then college-educated native born Asian American men have yet to reach full wage parity with whites. Although Asian Americans tend to live in high wage/high cost of living regions and states, this may not derive from a lack of labor market opportunities nationally. Rather, this may be due to personal proclivities and family ties that are associated with being more likely to have previously lived in those areas. In keeping with traditional Asian cultural norms, Asian Ameri- cans may be more concerned than are whites with residing near or with aging parents (Kamo, 2000; Xie & Goyette, 2004). Asian Americans as a group have been characterized as being more family oriented in the sense of being more likely to marry after completing schooling, less likely to become divorced, more likely to focus on the schooling achievements and related childrearing activities of their children, and more likely to form three-generational families (Kamo, 2000; Min, 1995; Sun, 1998; Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 159  I. TAKEI ET AL. Xie & Goyette, 2004). Some evidence accordingly suggests that, despite being younger on average, Asian Americans have higher levels of home equity than non-Hispanic whites (Krivo & Kaufman, 2004) in part due to the preference for larger homes. Because of this Asian American sub-cultural context that places a premium on family functioning, Asian Americans may not maximize their cost-adjusted earnings to the same extent that non-Hispanic whites do, but their residence may not derive from a lack of labor market opportunities nationally but rather may reflect the tendency of Asian Americans to prefer to live in places such as California despite the higher costs (Sa- kamoto, Kim, & Takei, 2008). In sum, region of residence probably entails a higher cost of living for Asian Americans than non-Hispanic whites, but the extent to which this pattern may be interpreted as deriving from racial and ethnic discrimi- nation in the labor market requires further investigation. Indeed, while the nearly majority Asian Americans still pre- fers to live in California and some other traditional residential states, an increasing size of Asian American population, espe- cially recent immigrants, do not live in their traditional residen- tial region of the West and reside in all geographic areas of the nation, especially to the South (Barringer, Gardner, & Levin, 1993; Sakamoto, Kim, & Takei, 2008). Although the vast ma- jority of Asian Americans were concentrated in the West prior to the twenty-first century, most Asian Americans now live outside of the West (i.e., in the South, Midwest or Northeast) (Sakamoto, Kim, & Takei, 2008). The South has recently over- taken the Northeast as the region with the second largest popu- lation of Asian Americans (Sakamoto, Kim, & Takei, 2008). Although Asian Americans may have greater preferences for living in high-cost areas such as California, contemporary American society is characterized by a high degree of geo- graphic mobility particularly among the college educated (Far- ley, 1996) who are disproportionately Asian American. Work- ers may be increasingly locating to places where the combina- tion of labor market opportunities, regional characteristics, and cost of living most suit their preferences. Region of residence in the contemporary labor market may thus no longer resemble a prelabor market factor. Indeed, larger proportion of native-born (i.e., a smaller proportion of foreign born) Asian Americans reside in the West (Sakamoto, Kim, & Takei, 2008). As sug- gested by Sakamoto, Kim, and Takei (2008), Asian Americans are entering into the social and geographic mainstreams of American society by successfully competing for its better jobs in all areas of the nation. The selectivity of contemporary Asian Americans in non- traditional region is documented in Sakamoto, Kim, and Takei (2008) who investigate current demographic characteristics of Asian Americans in the South. The authors find that Asian Ameri- cans, especially recent immigrants, are more likely than non- Hispanic whites to migrate to the region. In contrast to the ra- cial differentials in other regions, Asian Americans in the South have notably higher levels of education and hourly wages than non-Hispanic whites in the South. When compared to Asian Americans in other regions, Asian Americans in the South have higher levels of education, hourly wages, and employment in professional and technical occupations. After adjusting for re- gional differentials in the cost of living, Asian Americans in the South have higher levels of earnings, household income, and per-capita household income than Asian Americans in other regions. Overall, Sakamoto, Kim, and Takei (2008) interpret these results as suggesting the beginning of a new stage of Asian American history which is characterized by improved socioeconomic opportunities that are facilitating a movement away from the geographic margins of the nation such as Hawaii and California. Data and Methods We use data from the 2003 National Survey of College Graduates (NSCG). The sampling frame for this survey is na- tionally representative of all persons who responded in the 2000 U.S. Census that they had a college degree. The NSCG is a probability sample from that sampling frame and is representa- tive of the college-educated population in 2000. The NSCG includes information on the field of study of the highest degree obtained as well as earnings and basic demographic character- istics. It is the most recent micro-data on field of study that are available for the U.S. Regarding educational attainment, some highly informative data are provided by the 2003 NSCG. Investigating and con- trolling for the effects of educational attainment is important because recent studies suggest that the level of one’s completed schooling is increasingly significant in explaining wage ine- quality (Becker & Murphy, 2007; Kim & Sakamoto, 2008). For example, field of study has become another important dimen- sion of educational attainment that affects wages (Card & Di- Nardo, 2002; Kim & Sakamoto, 2008). Scientific, technical, engineering and math degrees (i.e., STEM) are well known to yield higher labor market rewards than degrees in the social sciences, humanities, and fine arts (Card & DiNardo, 2002; Kim & Sakamoto, 2008; Song & Glick, 2004). Because Asian Americans are well known to be much more likely to complete college (Sakamoto & Xie, 2006; Sakamoto, Goyette, & Kim, 2009; Xie & Goyette, 2004) as well as to be much more likely specialize in STEM fields (Goyette & Xie, 1999; Kim & Sa- kamoto, 2008; Sakamoto, Goyette, & Kim, 2009; Simpson, 2001; Xie & Goyette, 2003;), investigating the various effects of educational attainment is particularly apropos for evaluating the earnings of Asian Americans and the issue of whether they have achieved parity relative to whites. Another dimension of educational attainment is the prestige of the college or university that one attended. There is some evidence that Asian Americans are more likely to obtain their college degrees from higher status institutions (Sakamoto, Goyette, & Kim, 2009). Although highly imprecise, informa- tion regarding college prestige can be inferred from the Carne- gie classification of the institution that awarded the degree, which is provided by the 2003 NSCG. Using the 2003 NSCG therefore enables our analysis to obtain more informative re- sults about the extent to which Asian Americans are obtaining equivalent labor market rewards (in comparison with whites) on their various dimensions of educational attainment including college prestige. In order to ensure that our sample includes persons with some clear attachment to labor force participation, we limit the analysis to persons with positive earnings who were between the ages of 25 to 64, and who were working at least 1000 hours during the year prior to the surveys. This restriction ensures that only workers with some definite attachment to the labor force are included in the analysis. Note that persons who worked 1000 hours during the year prior to the survey include full-time workers who were employed half the year as well as part-time workers who were employed year round. The target population Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 160  I. TAKEI ET AL. is also restricted to those with positive earnings because nega- tive values tend to be associated with problems in the meas- urement of earnings for self-employed persons. The analysis differentiates Asian Americans in terms of those who were born overseas but who came to the US before the age of 13 in the US (whom we have referred to as the 1.5 genera- tion as is commonly done in the literature on Asian Americans) and native-born generations among Asian Americans. This distinction is made because the 1.5 generation may perhaps be regionally more mobile as well as somewhat distinctive in the wage determination patterns as they are the children of immi- grants who tend to be more motivated (Sakamoto, Goyette, & Kim, 2009). Nevertheless, the difference between the 1.5 and the native born is not really very clear from prior research, be- cause the former are perfectly fluent in English and familiar with American culture. Furthermore, most native born Asian Americans are second generation and are thus also the children of immigrants. Accordingly, the following analysis will give us better information about any differences (if there are any) be- tween 1.5- and native born Asian Americans in terms of their migration and earnings. For simplicity and to avoid excessive length, we focus on men only. Women’s migratory processes may be further com- plicated due to the even greater influences of spousal and fam- ily relations. For example, McKinnish (2008) finds that the earnings returns to migration are typically much larger for mar- ried men than for married women. For married women, the earnings returns to migration are actually often negative in that this group is much more likely (though not always) to be the “trailing spouse” in households where the maximization of the career development of the husband is given priority (Cooke et al., 2009). Variables The dependent variable that we analyze is log-earnings. The multiple regression functions that we estimate include di- chotomous variables to indicate the racial minority group (i.e., 1.5-generation Asian Americans and native-born Asian Ameri- cans) with native-born non-Hispanic whites serving as the ref- erence category. An additional dichotomous variable that we use is birth in the Pacific Division of the West (i.e., Washington, Oregon, California, Alaska, and Hawaii) because persons from California may have a greater proclivity to reside in California and because native-born Asian Americans are much more likely to be born in the state (Sakamoto, Kim, & Takei, 2008). Other demographic variables include years of age, marital status, and the number of children which are associated with migration preferences. The following discrete count variables indicate the number of children that reside in the respondent’s household—under age 2; between ages 2 - 5, between ages 6 - 11; and between ages 12 - 18. The analysis also includes two dichotomous variables to indicate the highest level of education completed (i.e., master’s degree and doctoral degree including professional degree versus bachelor’s degree as the reference category). The regression functions further control for the major field of study of the highest degree obtained (i.e., mathematics, life sciences, physical sciences, engineering, business, business fi- nance, education, medicine and pharmacy, and legal studies or law) with the reference category being social sciences, medical sciences, humanities, visual or performing arts, communica- tions, and majors reported as “other”. Furthermore, the Carne- gie classification for the college awarding the highest degree is indicated by dichotomous variables for Research University I, Research University II, Doctorate Granting I, Doctorate Grant- ing II, Comprehensive I, and Liberal Arts I. The reference cate- gory includes Comprehensive II, two-year institutions, Liberal Arts II, Theological Seminars and Bible Colleges, Medical Schools and Medical Centers, Schools of Engineering and Technology, Schools of Art, Music, and Design, Schools of Law, a few other highly specialized institutions, and classifica- tions reported as “missing.” This study examines whether native-born and 1.5-generation Asian Americans are more likely than whites to reside in the West. We also investigate whether native-born and 1.5-gene- raiton Asian Americans have higher earnings than whites when broken down by West versus non-West. In addition to an OLS regression model, a switching regression model is used in order to account the possibility of sample selectivity between wages and region among men who are observed to reside in the West and in the non-West. This study can therefore ask, net of age, education, marital status, disability status, and selectivity, if there is no differential in earnings between Asian Americans and whites in the West, as well as in the non-West. We also examine whether the results differ across OLS and switching regression models which allow for selectivity in region of resi- dence. The switching regression model consists of three equations that are estimated simultaneously using maximum likelihood assuming trivariate normality between the error terms of these equations. In this approach, selectivity is empirically evident to the extent that the error term from the probit equation is corre- lated with the error for either of the two log-earnings regres- sions. In this case, men who are observed to currently reside in the West (or are observed not to currently reside in the West) have systematically different earnings than would a random sample of working-age men with the same values on the inde- pendent variables that were used as covariates in the log-earnings regression. The absence of any statistically significant correla- tion between the error terms indicates a lack of empirical evi- dence for selectivity between current residence in the West and earnings. In this latter case, OLS estimates are adequate to ob- tain unbiased estimates of these population-level relationships. Due to the complexity of estimating these models which are not based on closed-form solutions (as in OLS), proper specifica- tion of the regression model (e.g., including all of the relevant independent variables) is very useful to obtaining appropriate results. For this reason, we do not formally consider shorter model specifications such as a bivariate model. Switching Regression Models The particular approach that we investigate is an endogenous switching regression model with two behavioral regimes (i.e., one log-earnings regression for residence in the West and an- other log-earnings regression for residence in the non-West). Since the technical details of this model have been discussed elsewhere (Gamoran & Mare, 1989; Maddala, 1983; Mare & Winship, 1988), only its basic points are summarized here. The model consists of three equations: an earnings regression for each of the two regional outcomes (i.e., whether or not cur- rently reside in the West), and a probit equation predicting the individual’s regional residence outcome (i.e., the ith person’s Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 161  I. TAKEI ET AL. probability of residing in the West). The three equations are estimated simultaneously by maximum likelihood assuming that the error terms for the three equations may be correlated and follow a trivariate normal distribution. Let Z* denote the propensity to reside in the West, and as- sume that this variable is latent with the following index func- tion: γ ZX (1) such that Z = 1 if Z* > 0, Z = 0 otherwise. If Z = 1 then the per- son is observed to reside in the West while if Z = 0 then the person is observed to be residing outside of the West. Two more equations may now be defined as follows: 1111 β if 1YXu Z (2) and 0000 β if 0YXu Z (3) We observe Y1 when Z = 1 because Equation (2) refers to the wages of persons who reside in the West. For these men resid- ing in the West, Y0 is unobserved, latent, or missing (i.e., we do not observe what the wages of men currently residing in the West would have been had they decided not to reside in the West). Similarly, we observe Y0 when Z = 0 which refers to the wages of those who reside in the non-West. For these latter men Y1 is missing (i.e., we do not observe what the wages of non- West residents would have been had they decided to reside in the West). This model is known as an endogenous switching regression model. As mentioned above, we use this model to address issues of self selection and the estimation of effects when there is non- random allocation of men in regard to current residence in the West net of measured covariates. Because of the selection problem (the failure to observe Y0 when Z = 1 and the failure to observe Y1 when Z = 0), we need to consider these outcomes in terms of this switching regression approach. For the men who are observed to currently reside in the West or who have, in other words, self-selected into current residence in the West, mean wages may be derived as being given by: 11 1 1111 11 1υ |1|* 0|γ 0 |υγβυ|υ φγ β σΦγ EY ZEY ZEYXυ EYX XEX X XX (4) which follows due to the truncation of the distribution of Y1 from below. Note that σ1υ refers to the covariance between the error term of the current region equation and the error term of the current residence in the West equation. Similarly, mean wages for non-West residence or in other words, those who have self-selected into not currently reside in the West is given by: 00 0 0000 00 0υ |0 |*0|γυ0 |υγ βυ|υ φγ βσ1Φγ EY ZEY ZEYX EYX XEXy X XX (5) which follows from truncation of Y0’s distribution from above. In this case, σ0υ refers to the covariance between the error term of the West residence equation and the error term of the non-West residence equation. This switching regression model allows for the possibility that error terms are correlated which occurs to the extent that σ1υ and σ0υ are non-zero. In this case, OLS estimates are biased due to sample selection (e.g., Falaris, 1988). Falaris (1988: p. 515) notes in that “[i]f unobserved characteristics of individuals affect both their choice of location and their wages, and if we use OLS to estimate location-specific wage equations to be used in obtaining predicted wages, these wages equations may suffer from sample selection bias.” The switching regression approach allows for the possibility of sample selection and thus provides more informative results than can be obtained by only using OLS. This model does not, however, assume that sample selectiv- ity is necessarily present. Instead, we can empirically test for sample selection bias by assessing whether the correlation be- tween the error terms of the current residential region regres- sion and either log-earnings regression is not zero. If the em- pirical results indicate that we cannot reject the hypotheses that σ1υ = 0 and σ0υ = 0, then we can actually go back to using OLS to obtain unbiased estimates because in this particular case there is no evidence for sample selection. On the other hand, if the empirical results indicate that either σ1υ or σ0υ are not equal to zero, then the estimation procedure needs to take into ac- count these non-zero correlations in order to correct for selec- tivity which would rule out the use of OLS. Empirical Findings Descriptive Statistics Table 1 presents descriptive findings separately for the three age groups (age 25 - 35, 36 - 49, and 50 - 64). The table shows that while younger whites tend to have higher percentages with children than Asian Americans, elder Asian Americans tend to have higher percentages with children than whites. In regard to birth region, higher percentages of Asian Americans are found in the Pacific Division of the West (i.e., Washington, Oregon, California, Alaska, and Hawaii), while higher percentages of whites are found in the Northeast, Midwest, and South, across the age groups. It has to be noted, however, that the sampled Asian American population includes 1.5-generation people who were born overseas. There are also some important racial differentials in educa- tional attainment, college major, and school type. For example, while a higher percentage of whites tend to have college educa- tion, a higher percentage of Asian Americans tend to have doc- toral or professional degrees. This is more apparent among the younger and middle-aged groups. Regarding college majors, a higher percentage of Asian Americans tend to major in mathe- matics, engineering, and medicine and pharmacy, while a higher percentage of whites tend to major in business and edu- cation. In regard to school type, Asian Americans are more likely to select Research University I, while whites tend to choose Research University II and Doctoral Granting I. Finally, the descriptive findings show that whites tend to have higher average salary than Asian Americans across age groups. Nev- ertheless, it should be noted that the Asian population includes the 1.5-generation, who may experience lower levels of salary due to other reasons than labor market discrimination, such as lack of English ability and unfamiliarity with the U.S. labor market and culture. We will later examine the net effects of Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 162  I. TAKEI ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 163 Table 1. Descriptive statistics for Non-Hispanic Whites and Asian Americans. Non-Hispanic White Asian Non-Hispanic White Asian Non-Hispanic White Asian 25 - 35 36 - 49 50 - 64 Age Group Mean Std. Dev. Mean Std. Dev.Mean Std. Dev.Mean Std. Dev.Mean Std. Dev. Mean Std. Dev. Age 31.403 2.638 31.027 2.749 42.749 3.944 41.911 3.982 55.513 3.894 54.449 3.702 Age-Squared 993.105 163.340 970.230169.3601843.061336.4271772.379337.1673096.861 438.816 2978.321413.592 Married 0.732 0.443 0.557 0.497 0.849 0.358 0.803 0.398 0.863 0.344 0.830 0.376 Children under Age 2 0.298 0.501 0.192 0.417 0.105 0.334 0.146 0.377 0.011 0.132 0.019 0.138 Children Aged 2 - 5 0.325 0.592 0.188 0.467 0.280 0.553 0.373 0.603 0.020 0.166 0.035 0.201 Children Aged 6 - 11 0.159 0.468 0.089 0.361 0.584 0.812 0.521 0.752 0.088 0.345 0.167 0.479 Children Aged 12 - 18 0.027 0.202 0.012 0.129 0.554 0.840 0.316 0.661 0.311 0.636 0.388 0.708 Disability Status 0.023 0.149 0.019 0.138 0.050 0.217 0.040 0.195 0.103 0.304 0.112 0.316 Born in Northeast 0.261 0.439 0.130 0.337 0.285 0.451 0.070 0.255 0.297 0.457 0.064 0.245 Born in Midwest 0.349 0.477 0.097 0.296 0.337 0.473 0.061 0.240 0.330 0.470 0.058 0.234 (Born in South) 0.238 0.426 0.074 0.261 0.227 0.419 0.044 0.206 0.233 0.423 0.035 0.185 Born in Non-Pacific Division of the West 0.052 0.222 0.013 0.113 0.048 0.214 0.018 0.133 0.043 0.202 0.038 0.193 Born in Pacific Division of the West 0.100 0.300 0.151 0.358 0.102 0.303 0.295 0.456 0.097 0.296 0.510 0.501 Educational Attainment (College Degree) 0.686 0.464 0.565 0.496 0.607 0.489 0.567 0.496 0.495 0.500 0.529 0.500 Master’s Degree 0.215 0.411 0.266 0.442 0.258 0.438 0.252 0.434 0.307 0.461 0.263 0.441 Doctoral and Professional Degree 0.060 0.238 0.123 0.328 0.074 0.261 0.106 0.308 0.092 0.289 0.109 0.312 Major Degree Field Mathematics 0.083 0.277 0.108 0.311 0.083 0.275 0.103 0.304 0.051 0.219 0.035 0.185 Life Sciences 0.060 0.237 0.058 0.234 0.052 0.223 0.055 0.229 0.056 0.230 0.087 0.282 Physical Sciences 0.040 0.196 0.025 0.155 0.042 0.201 0.028 0.164 0.043 0.202 0.029 0.168 Engineering 0.249 0.432 0.295 0.457 0.240 0.427 0.306 0.461 0.171 0.376 0.218 0.414 Business 0.120 0.325 0.090 0.287 0.150 0.358 0.130 0.336 0.138 0.345 0.135 0.342 Business Finance 0.046 0.209 0.040 0.196 0.050 0.218 0.046 0.209 0.041 0.197 0.061 0.240 Education 0.050 0.218 0.021 0.142 0.050 0.218 0.018 0.133 0.098 0.298 0.048 0.214 Medicine and Pharmacy 0.029 0.166 0.084 0.277 0.039 0.194 0.064 0.244 0.050 0.218 0.061 0.240 Legal Studies 0.031 0.174 0.027 0.162 0.032 0.176 0.029 0.167 0.040 0.196 0.038 0.193 Carnegie Classification Research University I 0.343 0.475 0.476 0.500 0.333 0.471 0.445 0.497 0.355 0.479 0.506 0.501 Research University II 0.110 0.313 0.066 0.248 0.103 0.303 0.073 0.261 0.100 0.300 0.054 0.227 Doctorate Granting I 0.076 0.265 0.054 0.227 0.076 0.266 0.031 0.174 0.073 0.260 0.032 0.176 Doctorate Granting II 0.070 0.255 0.059 0.236 0.077 0.266 0.062 0.242 0.066 0.248 0.061 0.240 Comprehensive I 0.226 0.418 0.195 0.396 0.229 0.420 0.244 0.430 0.238 0.426 0.205 0.404 Liberal Arts I 0.029 0.168 0.017 0.129 0.022 0.148 0.001 0.035 0.021 0.144 0.010 0.098 Salary 63,664 40,402 73,079 49,817 86,523 63,579 88,086 59,890 87,651 70,072 85,150 43,527 Log-Salary 10.909 0.626 11.014 0.795 11.180 0.683 11.217 0.626 11.141 0.785 11.212 0.591 Sample Size 5824 775 12,573 833 10,808 312 Variables in parentheses are omitted categories used in regression models.  I. TAKEI ET AL. Asian Americans in terms of salary, net of socioeconomic and demographic factors and selectivity. Table 2 presents the estimates of probit model which comes from the selection equation, predicting whether or not a work- ing-age man is observed to currently reside in the West. Table 2 also presents sample sizes of Asian Americans and whites by three age groups. The analysis is separately conducted by dif- ferent age categories, because age is usually a significant factor affecting wages especially in the case of men. Table 2 shows that the great majority of the sampled observations (i.e., 93 percent) are whites, and that whites are the majority across the three age groups (87 percent of the younger; 93 percent of the middle-aged; and 97 percent of the older). Therefore, the find- ings on selectivity which are discussed below are largely attrib- uted to the characteristics of whites, rather than those of Asian Americans. Results show that Asian Americans are more likely than whites to currently reside in the West, regardless of age cate- gory and nativity. One might hypothesize that 1.5-generation Asian Americans are less likely than whites to live in the West, because their parents are recent immigrants who are more likely to live in other regions with lower cost of living. Nevertheless, findings from the probit model indicate that 1.5-generation Asian Americans are also more likely than whites to reside in the West. The probit model also includes four dummy variables indi- cating one’s birth region (i.e., the Northeast, Midwest, Western Pacific Division, and Western non-Pacific Division, with the South serving as the reference category). The results show that men who were born in the Midwest, Western Pacific Division, and Western non-Pacific Division are more likely than those who were born in the South to currently reside in the West. However, there is no statistically significant differential in the probability of currently residing in the West, between men who were born in the Northwest and those who were born in the South. As such, findings suggest that migration into the West is common among men who were born outside of this area, except the Northeast. Table 3 presents estimates of OLS and switching regression models for log-salary. For simplicity, only the coefficients for native-born and 1.5-generation Asian Americans across the regions (i.e., current region is in the West or not) for each age category are presented. However, the results were obtained net of age, marital status, disability status, education, college major, and college type. It has to be noted first that the correlations (rho) on the last column of Table 3 indicate whether we can refer to the results from OLS or should refer to those from switching regression models. The statistically significant correlations (rho) for the West indicate a positive selection into living in the West (i.e., Asian Americans and whites are more likely to earn if they currently reside in the West). On the other hand, the statistically significant correlations for the non-West indicate a negative selection into living in the non-West (i.e., Asian Americans and whites are less likely to earn if they currently reside in the West). It should be noted that, since the great majority of the Table 2. Estimates of probit model for residing in the West. Age 25 - 35 Age 36 - 49 Age 50 - 64 Age 25 - 64 Native-Born AA 0.333* (n = 360) 0.551* (n = 407) 0.603* (n = 220) 0.514* (n = 987) 1.5-Gen. AA 1.007* (n = 415) 0.990* (n = 426) 1.296* (n = 92) 1.119* (n = 933) Born in the Northeast 0.010* –0.073* 0.043* 0.003* Born in Midwest 0.183* 0.180* 0.296* 0.230* Born in Pacific Division 1.443* 1.872* 1.904* 1.902* Born in Non-Pacific Divis 1.434* 1.866* 1.853* 1.864* Sample size for Whites 5824* 12,573* 10,808* 29,205* Note: The model controls for age, marital status, number of children, educational level, college major, and college type. *p < 0.001. Table 3. OLS and switching regression models of log-salary. OLS Switching Regression Age Group Current Region Native-Born AA 1.5-Gen. AA Native-Born AA 1.5-Gen. AA rho All Ages (25 - 64) West –0.002 0.062 0.013 0.065 0.035 Non-West –0.075* 0.077** –0.078* 0.074* –0.011 Younger (25 - 35) West 0.116* 0.111* 0.140** 0.122* 0.803*** Non-West –0.073 0.142** 0.076 0.359** 0.110* Middle-Aged (36 - 49) West –0.063 –0.008 –0.038 –0.005 0.061* Non-West –0.011 0.017 –0.009 0.019 0.007 Older (50 - 64) West 0.019 0.105 0.015 0.104 –0.007 Non-West –0.089 0.052 –0.102 0.040 –0.032 Note: The models control for age, education, marital status, disability, college major, and college type. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 164  I. TAKEI ET AL. sampled population is whites, these two different types of se- lectivity largely derive from the sampled white population. Since correlations for the older are not statistically significant, it is assumed that we can refer to the results from OLS for this age group. Namely, we can assume that there is no selectivity (e.g., men who reside in the West have more earnings) for this age group. The regression results for elder people indicate that there is no significant differential in earnings between Asian Americans and whites, regardless of nativity and current resi- dential region. The results for all ages indicate that salaries for both na- tive-born and 1.5-generation Asian Americans in the West do not significantly differ from those of whites in the West. In the non-West, native-born Asian Americans have 7 percent (i.e., e–0.075 – 1) lower earnings while 1.5-generation Asian Ameri- cans have 8 percent (i.e., e0.077 – 1) higher earnings than whites, net of other variables. As such, for all ages and older group, there is a lack of empirical evidence for selectivity between current residence in the West and earnings. On the other hand, the statistically significant correlations (rho) for the younger group indicate that we should refer to the findings from switching regression models rather than those of OLS, because error terms are correlated in the selection equa- tion. First, it has to be noted that the coefficients for Asian Americans in this age group are statistically significant and positive, except for the native-born in the non-West. Namely, the results show that both in the West and non-West, both na- tive-born and 1.5-generation Asian Americans aged 25 - 35 have significantly higher earnings (i.e., e0.140 – 1 or 15 percent higher earnings for native-born Asian Americans in the West; e0.122 – 1 or 13 percent higher earnings for 1.5-generation Asian Americans in the West; and e0.359 – 1 or 43 percent higher earn- ings for 1.5-generation Asian Americans in the non-West;) than whites after taking into account other variables and selectivity. Namely, the results indicate a positive advantage in earnings for Asian Americans both in the West and non-West, except for the native-born in the non-West. A significant positive selectivity is also found in the mid- dle-aged Asian Americans living in the West. Although the regression coefficients per se are not statistically significant, the correlation (rho) for the West (r = 0.061) indicates a significant positive selection into living in the West for Asian Americans and whites who are aged 36 - 49. Yet, the switching regression coefficients do not indicate any significant differential in sala- ries across Asian Americans and whites. Selectivity is an additional effect that is contained in the error term. It may indicate motivation, personality, and competitive- ness that are positively correlated with one’s labor market out- comes. However, the switching regression model does not en- able us to identify any specific components. Some speculations are that, Asian Americans and whites who currently reside in the West (especially California) are more advantaged because they have to stay productive in their work performance so that they can remain in California where many workers have a pref- erence reside due to its desirable features including good weather and other regional amenities. Or California residents are more eager to take higher-paying jobs to manage high rents and property taxes to remain in the state. Again, however, this positive selection residing in the West largely derives from characteristics of the white population in NSCG. Unfortunately, we cannot tell the extent to which this observed positive selec- tion of living in the West holds for Asian Americans. On the other hand, Asian Americans and whites in the non- West appear to be less competitive. Yet, again, this negative selection into living into the West largely derives from the white population. It might be possible, for example, to argue that Asian Americans in the non-West are actually more com- petitive in terms of labor market characteristics than their com- parable whites in the non-West, considering the higher mean earnings for Asian Americans in the non-West, especially for the younger 1.5-generation (e0.359 – 1 or 43 percent higher earn- ings for 1.5-generation Asian Americans in the non-West than whites) as found in Table 3. In sum, the findings show the following three important pat- terns. First, net of age, marital status, disability status, educa- tional level, college major, and college type, both native-born and 1.5-generation Asian Americans are more likely than whites to live in the West, regardless of age category. Second, net of the same variables, there is no significant differential in average earnings between whites and native-born Asian Ame- ricans in the West, as well as between whites and 1.5-genera- tion Asian Americans in the West (except that the younger, native-born and 1.5-generation Asian Americans have 12 per- cent higher earnings than whites in the West) than their compa- rable whites. On the other hand, native-born Asian Americans in the non-West are disadvantaged (i.e., 7 percent lower or e–0.075 – 1) in terms of average salaries than whites in the non-West, while 1.5-generation Asian Americans are advan- taged (i.e., 8 percent higher or e0.077 – 1) in terms of average salaries than whites in the non-West, net of other variables. Nevertheless, if the earnings differentials are separately exam- ined by three different age groups, Asian Americans in the non-West do not appear to have any earnings disadvantage in reference to whites in the non-West. Indeed, the younger 1.5- generation Asian Americans in the non-West have 43 percent higher (i.e., e0.359 – 1) earnings than younger whites in the non-West, net of other variables including selectivity. Finally, switching regression models demonstrate that both younger native-born and younger 1.5-generation Asian Ameri- cans in the West and 1.5-generation Asian Americans in the non-West have significantly higher average earnings than whites, after further controlling for selectivity. This indicates that the estimated earnings differentials for younger Asian Americans and whites are obscured when using OLS, which does not account for selectivity. In regard to selectivity, there is a positive selec- tion into living in the West, while the selection is negative liv- ing into the non-West. Since the great majority of the sampled population is whites, we cannot unfortunately tell the extent to which these positive and negative selectivity are attributed to Asian Americans. Conclusion Using both OLS and switching regression models, findings of this study indicate that net of age, education, marital status, disability, college major, and college type, there is no signifi- cant differential in earnings between college-educated Asian Americans (both 1.5-generation and native-born) in the West and their comparable white counterparts. This finding holds even when separately examined by three age groups. In the non-West, on the other hand, native-born Asian Americans are about 7 percent disadvantaged in terms of earnings, while 1.5- generation Asian Americans are about 8 percent advantaged in terms of earnings. The results from the switching regression Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 165  I. TAKEI ET AL. model show that selectivity entails in the findings for the younger age group—net of this selectivity, in addition to other variables including college major, both 1.5-generation and na- tive-born Asian Americans have significantly higher earnings than whites, whether or not in the current residential region is the West (except native-born Asian Americans in the non-West, whose earnings are not significantly different from those of whites). Positive selection into the West is also found for mid- dle-aged Asian Americans and whites. In regard to wages and earnings, the findings overall show that Asian American men (both 1.5-generation and native-born) do not face disadvantages in the US labor market, net of rele- vant factors. Switching regression models demonstrate that both younger native-born and 1.5-generation Asian Americans across the regions indeed have significantly higher average earnings than their comparable white counterparts, after further controlling for selectivity. This research suggests that Asian Americans do not face a significant net racial disadvantage in the labor market, as suggested by some research. Asian Ameri- cans had faced direct and overt racial discrimination in the la- bor market before World War II. Then this achievement of parity represents a historic change for native-born and 1.5- generation Asian Americans. Namely, racial and ethnic discrimi- nation in the post-Civil Rights era has been notably ameliorated (Alba & Nee, 1997; Farley & Alba, 2002), at least for Asian Americans. Findings of this study show that taking region and selectivity into account does not alter this significant conclu- sion. Although this research identifies selectivity among the younger-age and middle-aged groups, we cannot identify what kinds of characteristics constitute this selectivity. For example, the findings show a positive selection into currently living in the West and negative selection into the non-West. Selectivity may indicate motivation, personality, and competitiveness that are positively correlated with one’s labor market outcomes. However, switching regression models do not enable us to identify any specific components. Some speculations are that, Asian Americans and whites who currently reside in the West (especially in California) are more advantaged because they have to stay productive in their work performance, so that they can remain in California which has nice weather and amenities. Or California residents are more eager to take higher-paying jobs to manage high rents and property taxes to remain in the state. However, this positive selection residing in the West largely derives from characteristics of the sampled white popu- lation. Unfortunately we cannot tell the extent to which this ob- served positive selection of living in the West holds for Asian Americans. On the other hand, Asian Americans and whites in the non-West appear to be less competitive, as indicated by nega- tive selectivity. Yet, again, this negative selection into living into the West largely derives from the sampled white popula- tion. It might be possible, for example, to argue that Asian Americans in the non-West are actually more competitive in terms of labor market characteristics than their comparable whites in the non-West, considering the higher mean earnings for Asian Americans in the non-West, as found in switching regression models. Findings indeed suggest that 1.5-generation Asian Americans maintain high economic motivation which possibly derive from foreign-born parents. In sum, in addition to the issue of identifying what constitutes selectivity, the find- ings also do not enable us to see the extent to which the selec- tivity derives from characteristics of Asian Americans, because the great majority of the sampled population is whites. REFERENCES Alba, R., & Nee, V. (1997). Rethinking assimilation theory for a new era of immigration. International Migration Review, 31, 826-874. doi:10.2307/2547416 Allen, J. P., & Turner, E. J. (1988). We the people: An atlas of Amer- ica’s ethnic diversity. New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Com- pany. Barringer, H. R., Gardner, R. W., & Levin, M. J. (1993). Asian and Pacific Islanders in the United States. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. Barringer, H. R., Takeuchi, D. T., & Xenos, P. (1990). Education, oc- cupational prestige, and income of Asian Americans. Sociology of Education, 63, 27-43. doi:10.2307/2112895 Becker, G. S., & Murphy, K. M. (2007). Education and consumption: The effects of education in the household compared to the market- place. Journal of Human Capital, 1, 9-35. doi:10.1086/524715 Bonacich, E. (1972). A theory of ethnic antagonism: The split labor market. American Sociological Review, 37, 547-559. doi:10.2307/2093450 Bonacich, E. (1973). A theory of middlemen minorities. American So- ciological Review, 38, 583-594. doi:10.2307/2094409 Bonacich, E., & Modell, J. (1980). The economic basis of ethnic soli- darity. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Boswell, T. E. (1986). A split labor market analysis of discrimination against Chinese immigrants, 1850-1882. American Sociological Re- view, 51, 352-371. doi:10.2307/2095307 Bratsberg, B., & Ragan, J. F. (2002). The impact of host-country schooling on earnings. Journal of Human Resources, 37, 63-105. doi:10.2307/3069604 Cabezas, A. & Kawaguchi, G. (1988). Empirical evidence for continu- ing Asian American income inequality: The human capital model and labor market segmentation. In G. Y. Okihiro, J. M. Liu, A. A. Hansen, & S. Hune (Eds.), Reflections on shattered windows: Prom- ises and prospects for Asian American studies (pp. 144-164). Pull- man, WA: Washington State University Press. Card, D., & DiNardo, J. E. (2002). Skill-biased technological change and rising wage inequality: Some problems and puzzles. Journal of Labor Economics, 20, 733-783. doi:10.1086/342055 Chin, A. (2005). Long-run labor market effects of Japanese American internment during World War II on working-age male internees. Journal of Labor Economics, 23, 491-525. doi:10.1086/430285 Chin, G. J., Cho, S., Kang, J., & Wu, F. (1996). Beyond self-interest: Asian Pacific Americans toward a community of justice, a policy analysis of affirmative action. Asian Pacific American Law Journal, 4, 129-162. Chiswick, B. R. (1983). An analysis of the earnings and employment of Asian-American Men. Journal of Labor Economy, 1, 197-214. doi:10.1086/298010 Cooke, T. J., Boyle, P., Couch, K., & Feijten, P. (2009). A longitudinal analysis of family migration and the gender gap in earnings in the United States and Great Britain. Demography, 46, 147-168. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0036 Espenshade, T. J., & Fu, H. (1997). An analysis of English-language proficiency among US immigrants. American Sociological Review, 62, 288-305. doi:10.2307/2657305 Falaris, E. M. (1988). Migration and wages of young men. Journal of Human Resources, 23, 514-534. doi:10.2307/145811 Fang, D. (1996). Japan’s growing economic activities and the attain- ment patterns of foreign-born Japanese workers in the United States, 1979 to 1989. International Migration Review, 30, 511-534. doi:10.2307/2547392 Farley, R. (1996). The new American reality: Who we are, how we got here, where we are going. New York, NY: Russell Sage. Farley, R., & Alba, R. (2002). The new second generation in the United States. International Migration Review, 36, 669-701. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7379.2002.tb00100.x Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 166  I. TAKEI ET AL. Feagin, J. R., & Feagin, C. B. (1993). Racial and ethnic relations. En- glewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Fong, T. P. (1998). The contemporary Asian American experience: Be- yond the model minority. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Fuji, E., & Mak, J. (1985). On the relative economic progress of US born Filipino men. Economic Development and Social Change, 34, 557-573. doi:10.1086/451479 Gamoran, A., & Mare, R. D. (1989). Secondary school tracking and educational inequality: Compensation, reinforcement or neutrality? American Journal of Sociology, 94, 1146-1183. doi:10.1086/229114 Goyette, K., & Xie, Y. (1999). Educational expectations of Asian American youths: Determinants and ethnic differences. Sociology of Education, 72, 22-36. doi:10.2307/2673184 Hirschman, C., & Snipp, C. M. (2001). The state of the American dream: Race and ethnic socioeconomic inequality in the United States, 1970- 1990. In D. B. Grusky (Ed.), Social stratification: Class, race and gender in sociological perspective (2nd ed., pp. 623-636). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Hurh, W. M., & Kim, K. C. (1989). The “success” image of Asian Americans: Its validity, and its practical and theoretical implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 12, 512-536. doi:10.1080/01419870.1989.9993650 Iceland, J. (1999). Earnings returns to occupational status: Are Asian Americans disadvantaged? Social Science Research, 28, 45-65. doi:10.1006/ssre.1998.0634 Ichihashi, Y. (1932). Japanese in the United States. Stanford, CA: Stan- ford University Press. Ichioka, Y. (1988). The Issei: The world of the first generation Japa- nese immigrants, 1885-1924. New York, NY: The Free Press. Jiobu, R. M. (1988). Ethnic hegemony and the Japanese of California. American Sociological Review, 53, 353-367. doi:10.2307/2095644 Kamo, Y. (2000). Racial and ethnic differences in extended family households. Sociological Perspectives, 43, 211-229. Kao, G. (1995). Asian-Americans as model minorities? A look at their academic performance. American Journal of Education, 103, 121- 159. doi:10.1086/444094 Kim, M. & Mar, D. (2007). The economic status of Asian Americans. In M. Kim (Ed.), Race and economic opportunity in the twenty-first century (pp. 148-184). New York: Routledge. Kim, C., & Sakamoto, A. (2008). Have Asian American men achieved labor market parity with white men? American Sociological Review, 75, 934-957. doi:10.1177/0003122410388501 Kitano, H. H. L. (1976). Japanese Americans: The evolution of a sub- culture. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Kitano, H. H. L., & Daniels, R. (2001). Asian Americans: Emerging minorities (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Ko, G. K., & Clogg, C. C. (1989). Earnings differentials between Chi- nese and whites in 1980: Subgroup variability and evidence for con- vergence. Social Science Research, 18, 249-270. doi:10.1016/0049-089X(89)90007-0 Krivo, L. J., & Kaufman, R. L. (2004). Housing and wealth inequality: Racial-ethnic differences in home equity in the United States. Demo- graphy, 41, 585-605. doi:10.1353/dem.2004.0023 Levine, G., & Montero, D. (1973). Socio-economic mobility among three generations of Japanese Americans. Journal of Social Issues, 29, 33-48. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1973.tb00071.x Lieberson, S. (1980). A piece of the pie: Black and white immigrants since 1880. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Lyman, S. M. (1974). Chinese Americans. New York: Random House. Lyman, S. M. (1977). The Asian in North America. Santa Barbara, CA: Clio Books. Maddala, G. S. (1983). Limited-dependent and qualitative variables in econometrics. New York: Cambridge University Press. Makabe, T. (1981). The theory of the split labor market: A comparison of the Japanese experience in Brazil and Canada. Social Forces, 59, 786-809. Mar, D. (1999). Regional differences in Asian American earnings dis- crimination: Japanese, Chinese, and Filipino American earnings in California and Hawaii. Amerasia Journal, 25, 67-93. Mare, R. D., & Winship, C. (1988). Endogenous switching regression models for the causes and effects of discrete variables. In J. S. Long (Ed.), Common problems in quantitative social research (pp. 132- 160). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Martinelli, P. C., & Nagasawa, R. (1987). Further test of the model minority thesis. Sociological Perspectives, 30, 266-288. McCall, L. (2001). Sources of racial wage inequality in metropolitan labor markets: Racial, ethnic, and gender differences. American So- ciological Review, 66, 520-541. doi:10.2307/3088921 McKinnish, T. (2008). Spousal mobility and earnings. Demography, 45, 829-849. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0028 McLemore, S. D. (1994). Racial and ethnic relations in America. Bos- ton, MA: Allyn and Bacon. Min, P. G. (1995). Asian Americans: Contemporary trends and issues. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Montero, D. (1980). Japanese Americans: Changing patterns of ethnic affiliation over three generations. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Okihiro, G. Y. (1994). Margins and mainstreams: Asians in American history and culture. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. Sakamoto, A., & Furuichi, S. (1997). Wages among white and Japanese American male workers. Research in Social Stratification and Mo- bility, 15, 177-206. Sakamoto, A., & Furuichi, S. (2002). The wages of native-born Asian Americans of the end of the twentieth century. Asian American Pol- icy Review, 10, 17-30. Sakamoto, A., & Kim, C. (2003). The increasing significance of class, the declining significance of race, and Wilson’s hypothesis. Asian American Policy Review, 12, 19-41. Sakamoto, A., & Woo, H. (2007). The socioeconomic attainments of second-generation Cambodian, Hmong, Laotian, and Vietnamese Americans. Sociological Inquiry, 77, 44-75. doi:10.1111/j.1475-682X.2007.00177.x Sakamoto, A., & Xie, Y. (2006). The socioeconomic attainments of Asian Americans. In P. G. Min (Ed.), Asian Americans: Contempo- rary trends and issues (pp. 54-77). Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press. Sakamoto, A., Goyette, K. A., & Kim, C. (2009). Socioeconomic at- tainments of Asian Americans. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 255-276. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115958 Sakamoto, A., Kim, C., & Takei, I. (2008). Moving out of the margins and into the mainstream: The demographics of Asian Americans in the new South. The Southern Demographic Association Annual Meeting, Greenville, SC. Sakamoto, A., Liu, J., & Jessie M. Tzeng, J. M. (1998). The declining significance of race among Chinese and Japanese American men. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 16, 225-246. Sakamoto, A., Wu, H., & Tzeng, J. M. (2000). The declining signifi- cance of race among American men during the latter half of the twentieth century. Demography, 37, 41-51. doi:10.2307/2648095 Simpson, J. (2001). Segregated by subject: Racial differences in the factors influencing academic major between European Americans, Asian Americans, and African, Hispanic, and Native Americans. The Journal of Higher Education, 72, 63-100. doi:10.2307/2649134 Snipp, C. M., & Hirschman, C. (2004). Assimilation in American soci- ety: Occupational achievement and earnings for ethnic minorities in the United States, 1970 to 1990. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 22, 93-117. doi:10.1016/S0276-5624(04)22004-2 Song, C., & Glick, J. E. (2004). College attendance and choice of col- lege majors among Asian-American students. Social Science Quar- terly, 85, 1401-1421. doi:10.1111/j.0038-4941.2004.00283.x Sun, Y. (1998). The academic success of East-Asian-American students: An investment model. Social Science Research, 27, 432-456. doi:10.1006/ssre.1998.0629 Takaki, R. (1998). Strangers from a different shore: A history of Asian Americans. New York: Little, Brown and Company. Sakamoto, A., Takei, I., & Woo, H. (2011). Socioeconomic differen- tials among single-racial and multi-racial Japanese Americans: Fur- ther evidence on assimilation in the post-civil rights era. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 34, 1445-1465. doi:10.1080/01419870.2011.539241 US Commission on Civil Rights. (1988). The economic status of Ameri- cans of Asian descent: An exploratory investigation. Clearinghouse Publication No. 95. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Of- fice. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 167  I. TAKEI ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 168 Waters, M. C., & Eschbach, K. (1995). Immigration and ethnic and racial inequality in the United States. Annual Review of Sociology, 21, 419-446. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.21.080195.002223 Wong, M. (1982). The cost of being Chinese, Japanese, Filipino in the United States: 1960, 1970, 1976. Pacific Sociological Review, 25, 59-78. Wong, P., Lai, C. F., Nagasawa, R., & Lin, T. (1998). Asian Americans as a model minority: Self-perceptions and perceptions by other racial groups. Sociological Perspectives, 41, 95-118. Woo, H., Sakamoto, A., & Takei, I. (2012). Beyond the shadow of white privilege? The socioeconomic attainments of second-generation South Asian Americans. Sociology Mind, 2, 23-33. doi:10.4236/sm.2012.21003 Xie, Y., & Goyette, K. (2003). Social mobility and the educational choices of Asian Americans. Social Science Research, 32, 467-498. Xie, Y., & Goyette, K. (2004). Asian Americans: A demographic por- trait. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. doi:10.1016/S0049-089X(03)00018-8 Yun, Y. (1977). Early history of Korean immigration to America. In H. Kim (Ed.), The Korean Diaspora, historical and sociological studies of Korean immigration and assimilation in North America (pp. 33- 46). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio, Inc. Zhou, M., & Kamo, Y. (1994). An analysis of earnings patterns for Chinese, Japanese, and non-Hispanic white males in the United States. Sociological Quarterly, 35, 581-602. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.1994.tb00418.x Zeng, Z., & Xie, Y. (2004). Asian Americans’ earnings disadvantage reexamined: The role of place of education. American Journal of So- ciology, 109, 1075-1108. doi:10.1086/381914

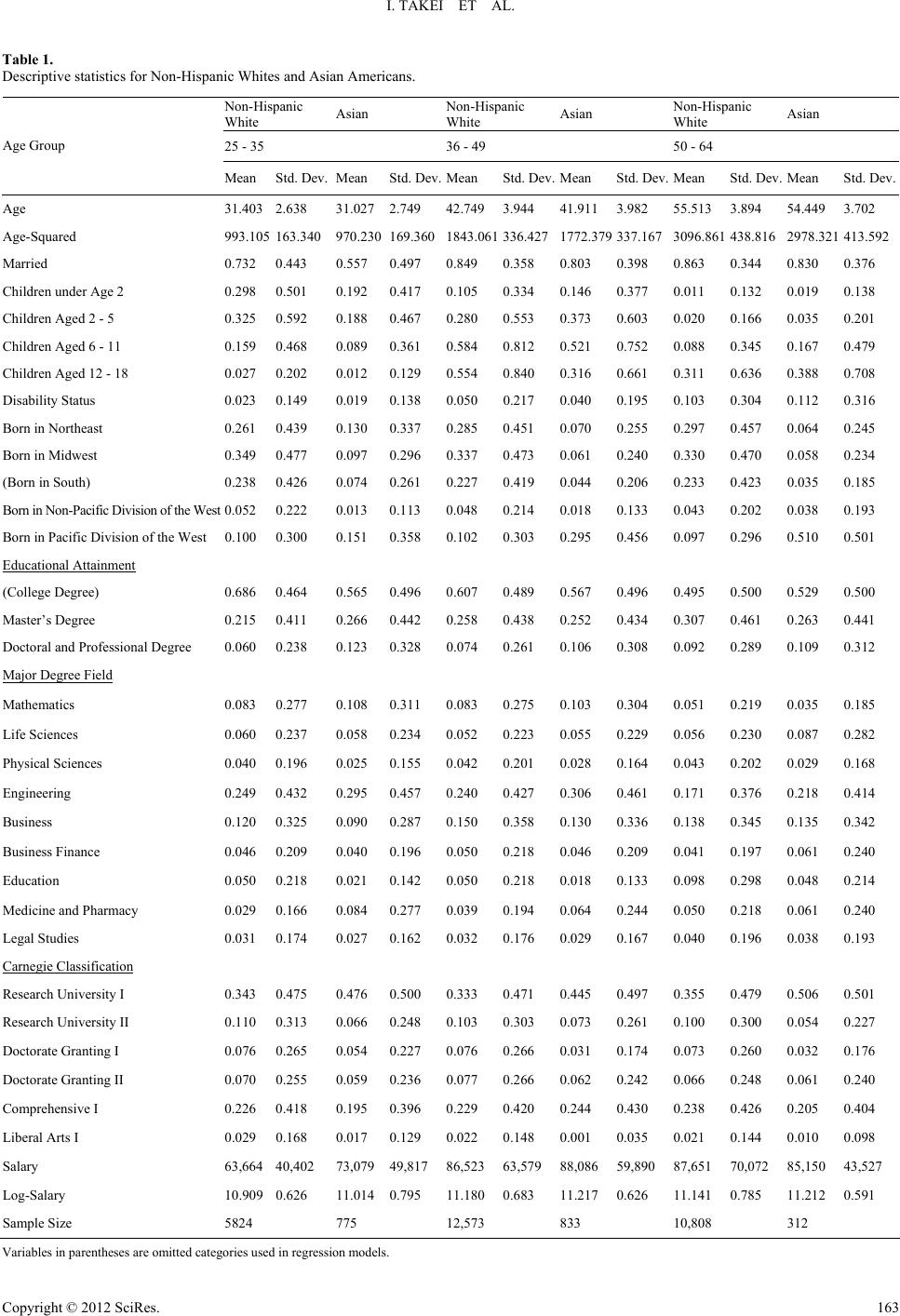

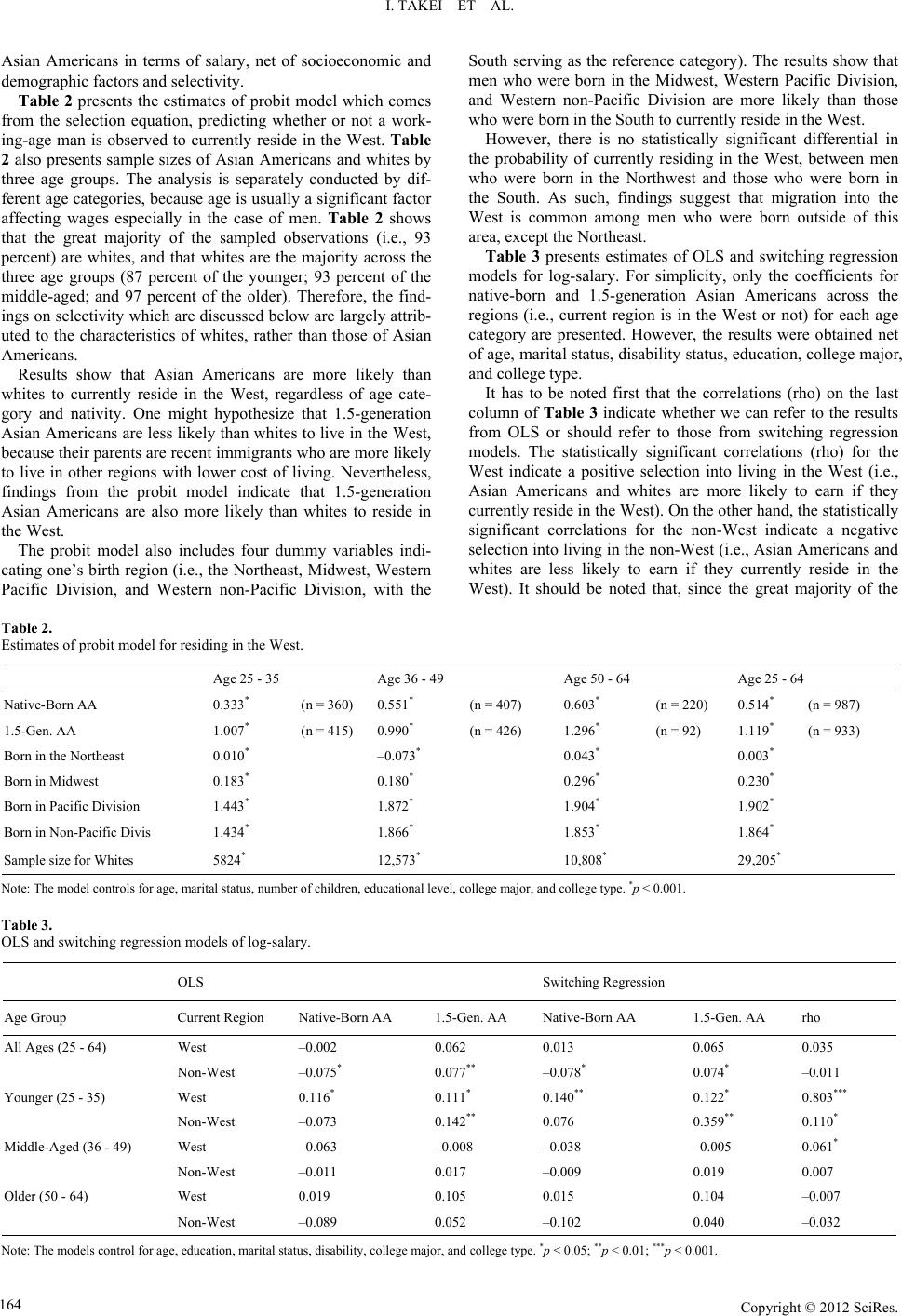

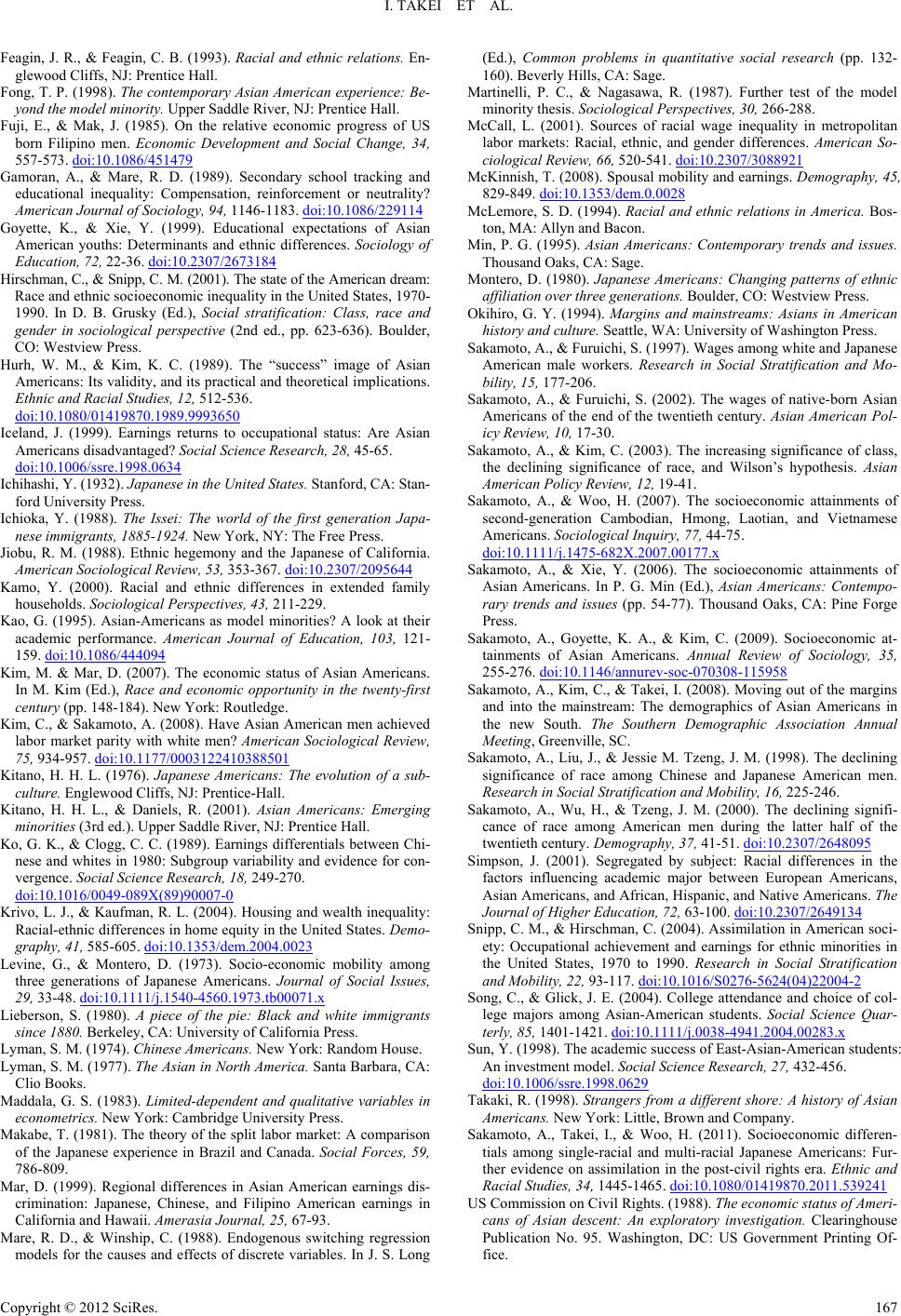

|