Psychology 2012. Vol.3, No.4, 364-369 Published Online April 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.34051 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 364 Bipolar Spectrum Disorders and Self-Concept among Males and Females with Parenting Roles Frank J. Prerost1*, Sharon Song2 1Department of Fam ily Medicine, Midwestern University, Downers Grove, USA 2Department of Biomedical Sciences, Midwestern University, Downers Grove, USA Email: *fprero@midwestern.edu Received February 2nd, 2012; revised February 28th, 2012; accepted March 29th, 2012 Bipolar spectrum disorders have been found to produce significant psychosocial costs for individuals and society. Although a number of studies have examined various psychosocial and psychological aspects as- sociated with the bipolar spectrum disorders, the research literature has been extremely limited when fo- cused on the parenting role. This current study examined the self-concept among parents who have been diagnosed with a bipolar spectrum disorder. A group of male and female parents with a diagnosis of a bi- polar spectrum disorder were assessed using the Tennessee Self-Concept Scales-2. Another group of males and females without a diagnosis of a bipolar spectrum disorder were also assessed for comparison using the same assessment tool. Compared to the non-bipolar parent group, results showed that partici- pants with a diagnosis of a bipolar spectrum disorder showed a significantly lower self-concept marked with doubts, concerns about academic/work performance, and perceptions of being physically diminished, inadequate, alienated, and unworthy of the family role. Findings from this study showed that parents with a bipolar spectrum disorder expressed negative perceptions related to inadequacy as a person across a number of self-concept dimensions. The results expanded upon current descriptions of the psychological dimensions found among individuals diagnosed with a bipolar spectrum disorder. Keywords: Self-Concept; Bipolar Disorders; Parenting Introduction The Mood Disorders described in the Diagnostic and Statis- tical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) are identified to be commonly occurring psychi- atric disorders (Bebbington & Ramana, 1995). The possible long-term consequences of the mood disorders have been found to range from spontaneous remission to a chronic presentation of symptoms (Galione & Zimmerman, 2010). The diagnostic separation of the mood disorders into Depressive Disorders and Bipolar Disorders used in the DSM-IV-TR has proved to be clinically and diagnostically useful (Perlis, Uher, Ostacher, Goldberg, Trivedi, Rush, & Fava, 2010). Support for this sepa- ration came from family studies, twin studies, and biological studies. Additional support has been garnered from the finding of differential clinical responses to treatment and long term outcomes found among persons diagnosed with depressive and bipolar disorders (Johnson, Meyer, Winett, & Small, 2000). Bipolar spectrum disorders have been characterized through abnormal mood swings that compose different levels of mood states including mania, hypomania, major depression and mixed states. Research has found that patients diagnosed with the bipolar spectrum disorders such as bipolar I disorder, bipo- lar II disorder, and cyclothymia, share many similarities in symptomatic presentation (Hirschfeld, 2001). Although the lifetime prevalence rate of bipolar I disorder has been reported to be approximately 1%, the prevalence of all of the bipolar spectrum disorders has been found to be substantially higher and impacts on a significant number of persons in our society (Hirschfeld, 2001). Research efforts have investigated a wide range of factors associated with the bipolar spectrum disorders including the causal factors for bipolar disorder, the personal and societal costs, psychosocial functioning, and effectiveness of various treatment and management modalities (Michalak & Murray, 2010). Yet a critical examination of the self-concept of parents who have been diagnosed with a bipolar spectrum disorder has been lacking in the scientific literature. Few studies have ex- plored the perceptions that individuals have developed about the bipolar disorder, and none have specifically examined how the notations about the psychiatric disorder have influenced developmental, behavioral or mental health concerns about their offspring or the actual parenting behaviors perfo rmed. Many studies have shown that bipolar spectrum disorders are associated with high rates of relapse that produced significant psychosocial, social and economic costs to society (Freeman, Freeman, & McElroy, 2002). Although many of the most per- sonally and socially destructive behaviors of bipolar spectrum disorders have been controlled through the application of psy- choactive medication, compliance has continued to be a sig- nificant problem (Perlis, Uher, Ostacher, Goldberg, Trivedi, Rush, & Fava, 2010). Bipolar spectrum disorders have been found to exact substantial financial, psychological, and societal costs even when individuals have received appropriate phar- macotherapy. Individuals with bipolar spectrum disorders have been considered to be prone to recurrences of problematic symptoms (Miklowitz & Alloy, 1999). Research has docu- mented substantial personal costs to the bipolar patients such as financial strain, occupational instability, and increased mortal- *Corresponding author.  F. J. PREROST ET AL. ity rate (Psbu, Brandt, Correia, Ekbom, & Sparen, 2001). Most individuals with bipolar spectrum disorders have been diagnosed during a depressive episode, but have showed great- est noncompliance with treatment when the depressed mood has dissipated (Angst & Marneros, 2001; Querques & Kontos, 2010). Researchers have found that a majority of patients with bipolar disorder have not achieved complete functional recov- ery (Pradham, Sinha, & Singh, 1999). Approximately 25% of persons diagnosed with bipolar spectrum disorders have not achieved full recovery (Pradham, Sinha, & Singh, 1999). Ge- netic factors, biological and cognitive vulnerabilities have been acknowledged in extended family studies to be significant in the etiology of bipolar spectrum disorder (Blackwood, Visscher, & Muir, 2001; Klimes-Dougan, Long, Lee, Ronsaville, Gold, & Martinez, 2010). Family and linkage studies have provided evidence for overlapping genetic susceptibility between bipolar spectrum disorders and schizophrenia (Bramon & Sham, 2001). This genetic component in the etiology of bipolar spectrum disorders has been readily reported in the media making the information readily accessible to individuals who are parenting offspring. Approximately half of the adult children who had a parent with a history of serious psychiatric disorder were found to display major psychological or substance abuse problems (Mowbrary, Bybee, Oysterman, MacFarlane, & Bowersox, 2006). Stressful life events and disturbances in social-familial sup- ports systems have been known to influence the cycling of the bipolar spectrum disorders (Rush, 2003; Leboyer & Kupfer, 2010). This continual triggering of the mood cycling has served to preserve negative ideas about the psychiatric condition (Bramon & Sham, 2001). Social support has been considered to be an important predictor of the frequency of mood cycling. Enhanced self-esteem that was bolstered through a strengthened social support system positively impacted on the clinical course of bipolar spectrum disorders (Kilbourne, Teh, Welsh, Pincus, Lasky, Perron, & Bauer, 2010). Effective psychosocial inter- ventions have improved adherence to medications, enhanced social-occupational functioning, and expanded the capacity of individuals to cope with environmental stressors (Johnson, Me- yer, Winett, & Small, 2000). Researchers and clinicians have called for an enhanced un- derstanding of the possible factors that may lead to improved psychosocial interventions among individuals with bipolar spe- ctrum disorders (Craighead & Miklowitz, 2000). Researchers have also emphasized the importance of trying to identify the factors that have prevented or impeded persons with bipolar spectrum disorder from seeking effective treatments (Struening, Perlick, Link, Hellman, Herman, & Sirey, 2001). Offspring and Parentin g C o nsideration s Persons who have been diagnosed with a bipolar spectrum disorder have often shown an intellectual curiosity about pedi- atric onset bipolar disorders. Many individuals have expressed the opinion that their diagnosis was missed in their youth (Wozniak, Biederman, & Richards, 2001). Up to sixteen per- cent of pediatric psychiatric referrals have been found with a presentation of symptoms associated with mania (Schraaufnael, Brumback, Harper, & Weinberg, 2001). Bipolar spectrum dis- orders have been recognized as a significant problem in all age groups with various indicators of bipolar spectrum disorders even recognized among prepubertal children (McNamara, Nan- dagopal, Strakowski, & DelBello, 2010). Treatment for bipolar spectrum disorders in children and adolescents has focused on a multimodal approach with an emphasis on psychosocial inter- ventions combined with pharmacotherapy (James & Javaloyes, 2001). At a roundtable convened by the National Institute of Mental Health, it was recommended that children with prepu- bertal bipolar spectrum disorders require particular monitoring of treatments and outcomes (Hyman, 2000). Assortative mating has been described as the tendency for individuals with similar phenotypes to form relationships. This phenomenon has been found to be a recurrent outcome among persons with bipolar spectrum disorders as individuals form intimate relationships and have had children (Mathews & Reus, 2010). But current research has not concluded if these couples have experienced any particular difficulty with their family roles and responsibilities. Using interviews and critical discourse analysis, it has been found that parents diagnosed with bipolar disorders reported a heightened need to monitor and moderate their emotions while teaching their children to do the same (Wilson & Crowe, 2009). Parents with bipolar spectrum disorder were found to endorse negative communication styles that produced limited personal expression in their children (Vance, Jones, Espie, Bentall, & Tai, 2009). Problems in communication were also described among parents with bipolar spectrum disorder in the context of not providing their children with an optimal environment for learning communicative skills (Oyserman, Mowbray, Meares, & Firminger, 2000). This current research endeavor was designed to assess self- concept among parents diagnosed with a bipolar spectrum. It was hypothesized that parents diagnosed with a bipolar spe- ctrum disorder would have a significantly lessened overall self- concept and diminished family self-concept in comparison to parents without a bipolar spectrum disorder. Further it was proposed that the bipolar parents would have lower self-concept and satisfaction in their life with enhanced conflict compared to those without a diagnosis of a bipolar spectrum disorder. Method Participants Thirty adults (25 women and 5 men) who had at least one child and had been diagnosed with a bipolar spectrum disorder volunteered for participation in this study. The participants were recruited from the community with radio and newspaper advertisements, and announcements at meetings of a regional support group for persons with bipolar spectrum disorders. The volunteers with bipolar disorder were paid $25.00 in considera- tion of their time and effort to participate in the study. Only adults who were 18 years and older, had children, and had re- ceived a formal diagnosis of a bipolar spectrum disorder were accepted into the study and assigned to the bipolar parent group. These 30 participants had a mean of 2.16 children and the fol- lowing characteristics: 23 Euro-American, 6 African-American, 1 Hispanic; 12 married, 9 divorced, 3 separated, 6 si ngle; 2 had not graduated from high school, 24 had earned some college credits. Participants in the non-bipolar parent group were recruited from the surrounding community. Thirty-eight adults (25 women and 13 men) volunteered for participation in the study. Inclu- sion into the non-bipolar parent group required an absence of a Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 365  F. J. PREROST ET AL. bipolar spectrum disorder, having children and being 18 years or older at the time of data collection. The non-bipolar parent group participants had a mean of 1.92 children and had the following characteristics: 31 Euro-American, 2 African-Ame- rican, 4 Hispanic, and 1 Asian; 35 had earned at least some college credit. The non-bipolar parent group participants did not receive any financial remuneration for volunteering to be part of the study. Before participation in this study, all the participants signed an informed consent form approved by the Midwestern Univer- sity Institutional Review Board (IRB). All procedures, materi- als, advertisements, and announcements used in this study were IRB approved. Materials All of the participants completed a demographic question- naire, and the Tennessee Self-Concept Scale-2, TSCS-2 (Fitts & Warren, 1996). The TSCS-2 was selected for this study be- cause it is comprised of self-concept scales that reflect directly on the issues being examined in this study and it has an estab- lished history of usage. The TSCS-2 was developed to examine self-concepts in 1988 and the current edition was revised in 1996. The TSCS-2 has been standardized on nationwide sam- ples from 7 to 90 years of age. The adult form used in this study is written at the third grade reading level and is designed for persons between the ages of 19 - 90 years. A five-point Likert-ty pe scale (1 = always fal se, 2 = mostly false, 3 = partly false and partly true, 4 = most ly true, 5 = always true) is used t o respond to 82 self-report questionnaire items that assess how individuals feel about them selves. The TSCS-2 is considered to have good psychometric prop- erties with coefficient alphas reported to range from .81 to .95. The test-retest reliability estimates for the TSCS-2 scale scores ranged from .62 to .82 (Lowe, Peyton, & Reynolds, 2007). High validity correlations between the TSCS-2 scales and those of other well known measures have been obtained (Lowe, Pey- ton, & Reynolds, 2007). The paper and pencil AutoScore Form of the TSCS-2 was used in this study. Scoring of each TSCS-2 AutoScore Form required approximately 10 minutes and provided 15 scores for each participant in the study. The TSCS-2 is made up of 4 va- lidity measures (inconsistent responding, self-criticism, faking good, response distribution), 6 measures of self-concept (phy- sical, moral, personal, family, social, academic/work), 2 sum- mary self-concept measures (total self-concept, conflict), and 3 supplementary measures (iden tity, satisfaction, behavior). Validity Scores The Inconsistent Responding (INC) score identifies if there is an unusually wide discrepancy in the person’s responses to 9 pairs of items with similar content. An example of an INC pair would be: “I have a healthy body” “I take good care of myself physically”. The Self-Criticism (SC) score indicates the degree to which a peson endorses mildly derogatory statements. It assesses whether a person is willing to admit to having com- mon frailties such as: “I am not as smart as the people around me.” Responses to nine statements make up the SC score. Fak- ing Good (FG) is an indicator of the tendency to project a falsely positive self-concept and make a favorable impression. An example of the 7 items of the FG score is: “I feel good most of the time”. The Response Distribution (RD) score is a meas- ure of certainty about self-perception and is designed to assess how extreme the responses were on the TSCS-2. The number of extreme rati ngs of “1” and “5” is calculated across all quest ions on the TSCS-2. Self-Concept Scores Physical Self-Concept (PHY) score represents the person’s view of physical health, sexuality, physical skill, and appea- rance. Fourteen items comprise the PHY score and includes the statement: “I am an attractive person”. The Moral Self-Concept (MOR) score describes the self from a moral/ethical perspective and measures a person’s satisfaction with personal conduct and control of impulses. The 14 items in the MOR score includes: “I am an honest person”. Personal Self-Concept (PER) score reflects the individual’s sense of personal worth, adequacy, and personal adjustment. There are 12 items in the PER score in- cluding: “I am a nobody”. The Family Self-Concept (FAM) score taps into the person’s feelings of adequacy and value as a family member. There are 12 statements for the FAM score and includes: “I am a member of a happy family.” The Social Self- Concept (SOC) score refers to the sense of adequacy and worth in relation to social interactions including peers apart from family and close friends. The 12 statements making up the SOC score includes: “I do not feel at ease with other people.” The Academic/Work Self-Concept (ACA) score measures self-per- ceptions in the context of school and work settings. There 12 items in the ACA score and includes: “Math is hard for me.” Summary Scores The Conflict (CON) score compares the extent of differentia- tion between self-concept through assertion versus disagree- ment with negative items. The CON score reflects ambivalence and is taken from 16 statements including: “I’ll never be as smart as other people.” The Total Self-Concept (TOT) score measures an individual’s overall self-esteem. The TOT score gives an indication if a person holds a generally positive or negative self-concept. Seventy-four statements in the TSCS-2 produce the TOT score and include the following statement: “I see something good in everyone I meet”. Supplementary Scores The Identity (IDN) score measures basic identity and how persons describe themselves. There are 21 statements in the IDN score and includes: “I am a friendly person”. The Satisfac- tion (SAT) score refers to the individual’s sense of self-satis- faction and degree of contentment with the self. There are 21 statements that make up the SAT score and include: “I wish I could be more trustworthy”. The Behavior (BHV) score meas- ures a person’s perception of actions and reflects on how indi- viduals describe themselves when referring to their behavior. The BHV score includes 20 items on the TSCS-2 including: “I do not act the way my family thinks I should”. Procedure Each participant was seen individually in an interview room where an informed consent form was reviewed and signatures collected before data collection began. Following completion of the demographic questionnaire, the participants completed the Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 366  F. J. PREROST ET AL. TSCS-2. The responses the participants provided on the demo- graphic questionnaire and the TSCS-2 were coded in a manner to assure anonymity. Results The data collected on the TSCS-2 was analyzed to test the hypothesis that individuals in the bipolar parent group would have a significantly diminished overall self-concept. Dimin- ished family self-concept in comparison to the non-bipolar parent group of participants without a bipolar spectrum disorder was also expected. Further, it was anticipated that the bipolar parent group would show lower levels of self-concept related to satisfaction in their life and enhanced conflict compared to the non-bipolar parent group. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients for the TOT score and subscales ranged from 0.727 to 0.855 which when compared to previously published guide- lines are in the good to acceptable categories (George & Mallery, 2003). The mean TOT score on the Tennessee Self-Concept Scales- 2 for the bipolar parent group was 39.77 with an 8.61 standard deviation. The non-bipolar parent group presented with a mean TOT score of 54.87 with a standard deviation of 8.42. An analysis of variance revealed a significant main effect (bipolar parent group compared to non-bipolar parent group), F = 7.23, p = 0.001 supporting the hypothesis that bipolar parent group participants would have a diminished self-concept. Multiple post-hoc t-tests on all of the TSCS-2 self-concept and supple- mental scales revealed significant support for the hypotheses related to family and satisfaction. The bipolar parent group participants showed lower life satisfaction (SAT), t = 7.92, p = 0.0001 and family self-concept (FAM), t = 6.77, p = 0.0001. Although a significant difference was not found for the CON Score, t = 0.30, p = 0.7651; significant findings for the Physical Self-Concept (PHY), t = 4.68, p = 0.0001; Moral/Ethical Self- Concept (MOR), t = 3.31, p = 0.0015; Personal Self-Concept (PER), t = 5.70, p = 0.0001; Social Self-Concept (SOC), t = 4.55, p = 0.0001; Academic/Work Self-Concept (ACA), t = 4.18, p = 0.0001; Identity (IDN), t = 5.85, p = 0.0001; and Be- havior (BHV), t = 4.85, p = 0.0001 lend support to the pro- posed negative impact of bipolar disorder on different aspects of self-concept among the bipolar parent group. The t-scores, means and standard deviations for all the valid- ity, self-esteem, and supplemental scales for the non-bipolar parent group and bipolar parent group are presented in Table 1. The pattern of outcomes on the validity scales, INC, SC, FB, and RD scores were indicative of good validity for the scores across the TSCS-2 self-concept and supplementary measures (Fitts & Warren, 1996). Discussion The results indicated that parents with a bipolar spectrum disorder showed a consistent and significant lessening of the self-concept across various dimensions compared to the non- bipolar parent group. The differences reached significance over several aspects of self-concept including total, physical, moral, personal, family, academic, identity, satisfaction and behavior. Feelings of inadequacy as related to self-concept appeared to be common among parents with a bipolar spectrum disorder. As related to self-concept these individuals questioned their abili- Table 1. Comparison of bipolar parent group with non-bipolar parent group on the Tennessee Self-Concept Scales-2 (TSCS-2) showing means, stan- dard deviations, t-scores and p values. TSCS-2 Self-Concept Score Bipolar Paren t Group M (SD) Non-Bipolar Parent Gro u p M (SD) t p-value Inconsistent Responding 57.93 (10.30) 48.79 (7.712) 2.470.0161 Self-criticism 45.90 (13.14) 46.18 (9.302) 0.010.9921 Faking Goo d 41.80 (9.443) 54.34 (9.346) 3.180.0022 Response Distribution 47.03 (12.69) 51.24 (9.960) 0.890.37 67 Physical 41.23 (9.895) 54.37 (12.54) 4.680.0001 Moral 44.37 (12.59) 52.45 (8.497) 3.310.0015 Personal 39.93 (10.95) 54.63 (10.07) 5.700.00 01 Family 40.00 (8.506) 52.82 (6.974) 6.770.0001 Social 44.10 (9.15 4) 53.34 (7.570) 4.550.0001 Academic 45.57 (10.09) 54.13 (6.625) 4.180.0001 Conflict 55.80 (13.99) 53.89 (9.003) 0.300.7651 Total 39.77 (8.5 67) 54.87 (8.418) 4.370.0001 Identity 38.93 (9.2 89) 53.29 (10.57) 5.850.0001 Satisfaction 38.63 (7.3 54) 52.66 (7.121) 7.920.0001 Behavior 42.77 (10.71) 53.89 (8.049) 4.850.0001 ties to succeed in the various settings. Parents with a bipolar spectrum disorder reported a sense of inadequacy that questioned their value as a family member. This finding may be considered to be an expansion on previ- ously reported research outcomes in which parents with bipolar disorder did not achieve full management of their symptoms during the course of the bipolar spectrum disorder. Without feeling in full control of the bipolar spectrum disorder constel- lation of symptoms, the parents may have questioned their value as a fully functioning family member. The results of the current study have shown a diminished physical self-concept that may have served as an impediment to perceiving the self as a fully functioning family member. This may have promoted a sense of alienation from th e fa mily. Previous research that used a structured interview format found that parents with bipolar disorder expressed a heightened need to monitor their emotional state (Wilson & Crowe, 2009). This need could be reflected in the impact on family self-con- cept in the form of alienation. The need to carefully monitor one’s emotional state may have set the parents apart from other family membe rs and contributed to a feeling of separateness or alienation from the m. Previous research has shown that individuals with bipolar disorder routinely experienced a reoccurrence of problematic symptoms that lessened their overall sense of well being (Mik- lowitz & Alloy, 1999). The current research showed that when compared to the participants who did not have a bipolar spec- trum disorder, the bipolar parent group reported a significantly diminished physical self-concept. Seemingly they saw them- selves as less physically well than others. It could be suggested that the experience of emotional cycling with the need for con- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 367  F. J. PREROST ET AL. tinuous use of mood stabilizing medications may have contrib- uted to an unhealthy view of the self. These current findings could be used to frame the previously reported outcomes that persons with a bipolar spectrum disorder had described them- selves as “broken” or less well than other people (Miklowitz & Alloy, 1999). Research has found poor social functioning among persons with bipolar disorder and this was believed to be related to diminished self-esteem (Johnson, Meyer, Winett, & Small, 2000). The current results revealed a low level of social and personal self-concept among the bipolar parent group. These individuals reported a low capacity to interact effectively in social situations in comparison to the non-bipolar parent group. Individuals with a bipolar spectrum disorder have expressed problems with communication that contributed to an environ- ment lacking in stimulation for the development of this skill in their children (Oyserman, Mowbray, Meares, & Firminger, 2000). The diminished personal self-concept found in this study among the bipolar parent group coincided with this previous research. The low self-concept may have inhibited meaningful communication with family members as well as with other per- sons. Research has marked the importance of having strong psychosocial and medical support systems for individuals di- agnosed with bipolar disorder (Craighead & Miklowitz, 2000). The findings in the current study which showed a diminished level of personal self-concept may be connected to a limited level of social support. The bipolar parent group scored lower on moral/ethical self- concept than the non-bipolar parent group. This may have been a reflection on the perception that they were a “bad” person and not a “good” one, and could have been related to the social stigma that has been associated with mental illness in our soci- ety. Many studies have concluded that persons with bipolar dis- order benefit from early diagnosis (Wozniak, Biederman, & Richards, 2001) and a multimodal approach to treatment (James & Javaloyes, 2001). Since the current study showed that vari- ous aspects of self-concept were diminished among the bipolar parent group, multimodal treatments could address the psycho- social components of bipolar disorder and assist with enhancing self-concept. Adult children of parents with bipolar disorder have been found to exhibit a high incidence of psychiatric and substance abuse problems (Mowbray, Bybee, Oysteman, Mac- Farlane, & Bowersox, 2006). The treatment modalities used for bipolar disorder may also be improved with the inclusion of parenting support interventions. Although the study obtained significant results the current research is limited through the sample size. But the significant outcomes suggest that future research efforts could be directed into the self-perceptions among parents with bipolar spectrum disorders in relationship to specific parenting skills. The con- cerns found among these participants about the adequacy of their self-concept and physical self may influence parenting behavior and attitudes. Future research could focus on parent- ing behaviors as the research variable among parents and non- parents with a bipolar spectrum disorder. Acknoweledgements This research was supported in part through a grant from the Tsang Foundation. The authors wish to thank Erenee Sirinian, DO for her assistance in the project. REFERENCES Angst, J., & Marneros, A. (2001). Bipolarity from ancient to modern times: Conception, birth and rebirth. Journal of Affective Disorders, 67, 3-19. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00429-3 Bebbington, P., & Ramana, R. (1995). The epidemiology of bipolar affective disorder. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 30, 279-292. doi:10.1007/BF00805795 Blackwood, D., Visscher, P., & Muir, W. (2001). Genetic studies of bipolar affective disorder in large families. British Journal of Psy- chiatry Supplement, 41 , 134-136. doi:10.1192/bjp.178.41.s134 Bramon, E., & Sham, P. (2001). The common genetic liability between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: A review. Current Psychiatry Reports, 3, 332-337. doi:10.1007/s11920-001-0030-1 Craighead, W., & Miklowitz, D. (2000). Psychosocial interventions for bipolar disorder. Jour na l of Cl in ic al Psychiatry, 61, 58-64. Fitts, W. H., & Warren, W. L. (1996). Tennessee self-concept scale (TSCS-2) manual . Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services. Freeman, M., Freeman, S., & McElroy, S. (2002). The comorbidity of bipolar and anxiety disorders: Prevalence, psychobiology, and treat- ment issues. Journal o f Affective Disorders, 68, 1-23. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00299-8 Galione, J., & Zimmerman, M. (2010). A comparison of depressed patients with and without borderline personality disorder: Implica- tions for interpreting studies of the validity of the bipolar spectrum. Journal of Personalit y Disorders, 24, 763-772. doi:10.1521/pedi.2010.24.6.763 George, D., & Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and referen c e (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Hirschfeld, R. (2001). Bipolar spectrum disorder: Improving its recog- nition and diagnosis. J ou rn al of C l in ical Psychiatry, 62, 5-9. Hyman, S. E. (2000). Goals for research on bipolar disorder: The view from NIMH. Biological Psychiatry, 48, 436-441. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(00)00894-5 James, A., & Javaloyes, A. (2001). The treatment of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychia- try, 42, 439-449. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00738 Johnson, S., Meyer, B., Winett, C., & Small, J. (2000). Social support and self-esteem predict changes in bipolar depression but not mania. Journal of Affective Disor d ers, 58, 79-86. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(99)00133-0 Kilbourne, A. M., The, C., Welsh, D., Pincus, H. A., Lasky, E., Perron, B., & Bauer, M. S. (2010). Implementing composite quality metrics for bipolar disorder: Towards a more comprehensive approach to quality measurement. General Hospital Psychiatry, 32, 636-643. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.09.011 Klimes-Dougan, B., Long, J. D., Lee, C. Y., Ronsaville, D., Gold, P. W., & Martinez, P. E. (2010). Continuity and cascade in offspring of bipolar parents: A longitudinal study of externalizing, internalizing and thought problems. Bipolar Disorders, 12, 627-637. Leboyer, M., & Kupfer, D. J. (2010). Bipolar disorder: New perspec- tives in health care and prevention. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71, 1689-1695. doi:10.4088/JCP.10m06347yel Lowe, P., Peyton, V., & Reynolds, C. (2007). Test score stability and the relationship of adult manifest anxiety scale-college version scores to external variables among graduate students. Journal of Psy- choeducational Assessment, 25, 69-81. doi:10.1177/0734282906293698 Mathews, C., & Reus, D. (2010). Assortative mating in the affective disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 42, 257- 262. doi:10.1053/comp.2001.24575 McNamara, R. K., Nandagopal, J. J., Strakowski, S. M., & DelBello, M. P. (2010) Preventative strategies for early-onset bipolar disorder: Towards a clinical staging model. Central Nervous System Drugs, 24, 983-996. Michalak, E. E., & Murray, G. (2010). Development of the QOL.BD: A disorder-specific scale to assess quality of life in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders, 12, 727-740. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00865.x Miklowitz, D., & Alloy, L. (1999). Psychosocial factors in the course and treatment of bipolar disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 368  F. J. PREROST ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 369 108, 558-588. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.108.4.555 Mowbrary, C., B ybee, D., O ysteman, D., MacFarl ane, P., & Bo wersox, N. (2006). Psychosocial outcomes for adult children of parents with severe mental illnesses: Demographic and clinical history predictors. Health and Social Work , 31, 99-108. doi:10.1093/hsw/31.2.99 Osby, U., Brandt , L., Correia, N., Ekbom, A., & Sparen, P. (2001). Excess mortality in bipolar and unipolar disorder. Archives of Gen- eral Psychiatry, 58, 844-850. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.844 Oyserman, D., Mowbray, C., Meares, P., & Firminger, K. (2000). Par- enting among mothers with a serious mental illness. American Jour- nal of Orthopsychiatry, 70, 296-315. doi:10.1037/h0087733 Pradham, S., Sinha, V., & Singh, T. (1999). Psychosocial dysfunctions in patients after recovery from mania and depression. International Journal of Rehabilitation Re se arch, 22, 303-309. doi:10.1097/00004356-199912000-00007 Perlis, R. H., Uher, R., Ostacher, M., Goldberg, J. F., Trivedi, M. H., Rush, A. J., & Fava, M. (2010). Association between bipolar spec- trum features and treatment outcomes in outpatients with major de- pressive disorder. Journa l of Affective Disorders, 17, 30-45. Querques, J., & Kontos, N. (2010). An approach to the patient with dysregulated mood: Major depression and bipolar disorder. Devel- opmental Psychopathology, 22, 849-866. Rush, A. (2003). Toward an understanding of bipolar disorder and its origin. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 64, 4-8. Schraaufnael, C., Brumback, R., Harper, C., & Weinberg, W. (2001). Affective illness in children and adolescents: Patterns of presentation in relation to pubertal maturation and family history. Journal of Child Neurology, 16, 553-561. Struening, E., Perlick, D., Link, B., Hellman, F., Herman, D., & Sirey, J. (2001). Stigma as a barrier to recovery: The extent to which caregiv- ers believe most people devalue consumers and their families. Psy- chiatry Service, 52, 1633-1638. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1633 Vance, Y., Jones, S., Espie, J., Bentall, R., & Tai, S. (2009). Parental communication style and family relationships in children of bipolar parents. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 47, 355-359. doi:10.1348/014466508X282824 Wilson, L., & Crowe, M. (2009). Parenting with a diagnosis bipolar disorder. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65, 877-884. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04954.x Wozniak, J., Biederman, J., & Richards, J. (2001). Diagnostic and therapeutic dilemmas in the management of pediatric onset bipolar disorder. Journal of Clin i ca l Psychiatry, 62, 10-15.

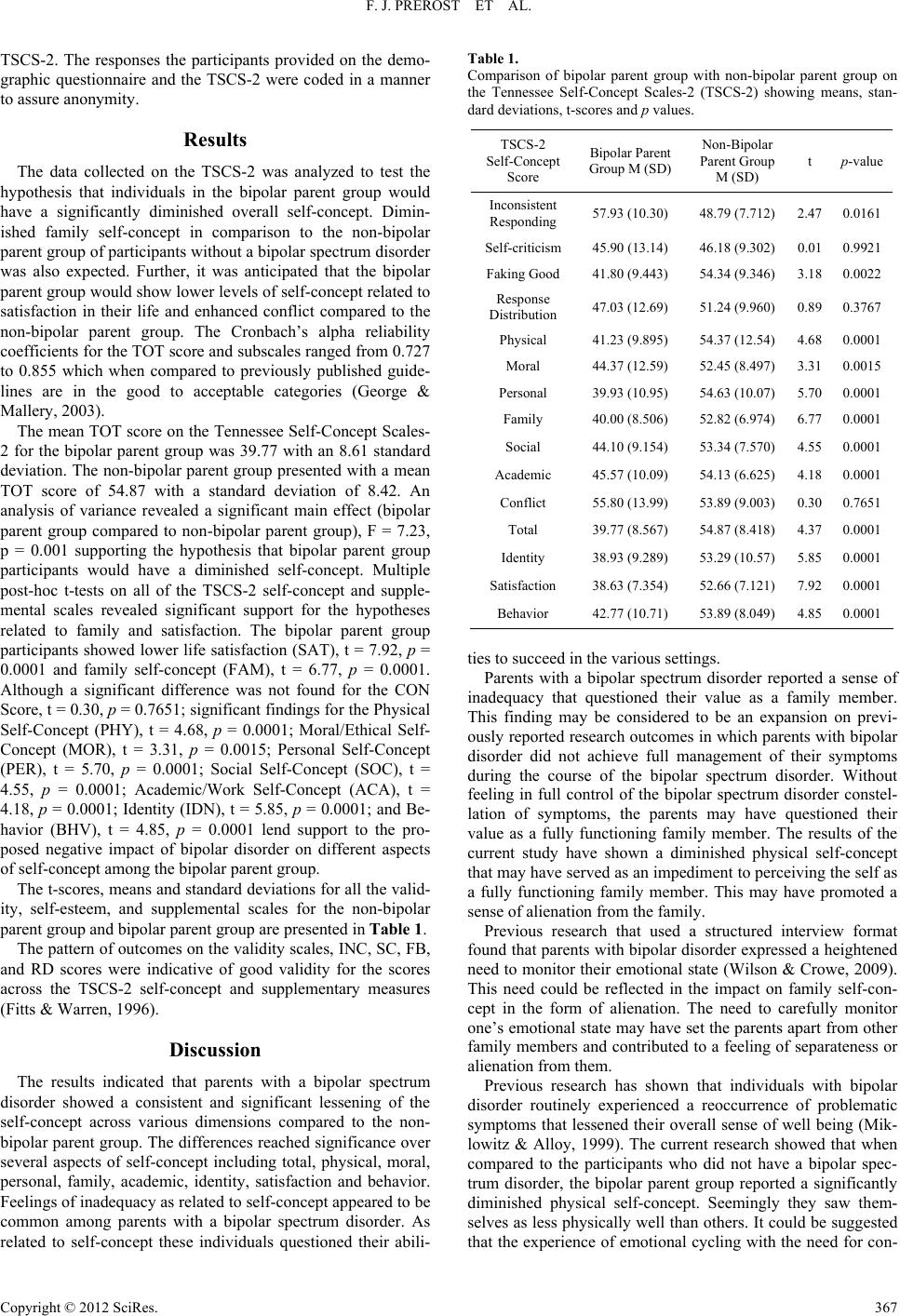

|